Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

13 Learning Outcomes For SUNY Cortland

Caricato da

madison.giannattasi0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

79 visualizzazioni9 pagineThe thirteen learning outcomes SUNY Cortland expects their teacher candidates to be educated in.

Titolo originale

13 Learning Outcomes for SUNY Cortland

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoThe thirteen learning outcomes SUNY Cortland expects their teacher candidates to be educated in.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

79 visualizzazioni9 pagine13 Learning Outcomes For SUNY Cortland

Caricato da

madison.giannattasiThe thirteen learning outcomes SUNY Cortland expects their teacher candidates to be educated in.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 9

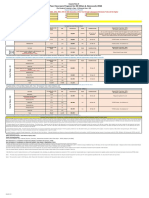

SUNY Cortland Teacher Education

Conceptual Framework Learning Outcomes

SUNY Cortland`s teacher education programs provide opportunities and experiences to ensure that candidates

develop the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required Ior eIIective teaching. The Iollowing thirteen proIiciencies

assure that SUNY Cortland teacher candidates will make a diIIerence in the classroom and beyond.

!"#$%&'(& *+,& - Candidates will:

1. Demonstrate a solid Ioundation in the arts and sciences;

2. Possess in-depth knowledge oI the subject area to be taught;

3. Understand how students learn and develop;

4. Manage classrooms structured in a variety oI ways to promote a saIe learning environment;

5. Know and apply various disciplinary models to manage student behavior.

6. Collaborate with other staII, the community, higher education, other agencies, and cultural institutions, as well as

parents and other caregivers, Ior the beneIit oI students;

7. Continue to develop proIessionally as ethical and reIlective practitioners who are committed to ongoing scholarly

inquiry;

,.+"'+/', - Candidates will:

8. Know state and national standards, integrate curriculum across disciplines, and balance historical and

contemporary research, theory, and practice;

9. Demonstrate appropriate proIessional dispositions to help all students learn;

'01&/,0.2 - Candidates will:

10. Apply a variety oI teaching strategies to develop a positive teaching-learning environment where all students

are encouraged to achieve their highest potential;

11. Foster understanding oI and respect Ior individuals` abilities, disabilities and diversity oI variations oI ethnicity,

culture, language, gender, age, class, and sexual orientation.

+,,&,,3&". - Candidates will:

12. Use multiple and authentic Iorms oI assessment to analyze teaching and student learning and to plan curriculum

and instruction to meet the needs oI individual students.

.&45"#%#(2 - Candidates will:

13. Demonstrate suIIicient technology skills and the ability to integrate technology into classroom teaching/

learning.

!"#$ &'()*+,- ./+01/( 2-30+)4',

&',0/5)3+* 6(+7/8'(9 :/+(,4,; <3)0'7/=

ELABORATED

!6789:;<: *=>:

Candidates should demonstrate a solid foundation in the arts and sciences. The philosophical commitment

to a solid Ioundation in the arts and sciences in our teacher education programs can be traced to the space John

Dewey (1916, 1938) granted Ior the liberal arts in connecting the growth oI democracy and sound educational

practice. Education must not only provide candidates the opportunity to acquire a broad Ioundation in the

arts and sciences; it must teach them to critically analyze that knowledge and to recognize its oIten contested

nature (e.g., Banks, 1999; Apple, 2004; Nieto and Bode, 2008).

Candidates should possess in-depth knowledge of the subject area to be taught. Alongside preparation in

pedagogy and methods, teachers` subject matter knowledge has consistently been shown to relate positively

with student achievement (e.g., Wiggins & McTighe, 1998; Darling-Hammond and Youngs, 2002; Marzano,

2009).

Candidates should understand how students learn and develop. EIIective teachers must be aware oI

theories oI child development and learning in order to select appropriate pedagogical strategies and materials

to support cognitive, social, physical, and emotional growth in all students (Darling-Hammond, 1998).

Candidates in the SUNY Cortland teacher education program acquire understanding oI a broad range

oI historical and contemporary developmental and learning theories (e.g., Gardner, 1993; Piaget, 1970;

Vygotsky, 1978).

Candidates must manage classrooms structured in a variety of ways to promote a safe and orderly

environment for learning and to teach the skills oI living responsibly in society (Butchart & McEwan,

1998). Candidates must demonstrate competence in establishing an optimal learning environment (Marzano,

Marzano & Pickering, 2009); they must understand the theoretical perspectives and practical applications

oI strategies Ior eIIective classroom management and discipline, ranging Irom humanistic to behaviorist

approaches. Candidates discuss classroom management, review a range oI models and begin developing their

approach, which will be ongoing throughout the program Teachers must be mindIul oI the diverse needs oI

students (Grossman, 2004) as well as aware that the skills and attitudes students learn are powerIully related

to the nature oI the society. Democracies give great power to citizens; responsible citizenship is built in some

part through what students learn Irom teachers` approach to classroom management and discipline (Ayers,

Kumashiro, Meiners, Quinn & Stovall, 2010). Candidates develop individual classroom plans, based on the

needs oI the students they will teach.

?@7A:>>B76=9 47CCBDC:6D>

Candidates promote parental involvement and collaborate effectively with other staff, the community,

higher education, other agencies, and cultural institutions as well as parents and other caregivers for

the benefit of students. Research demonstrates that Iamily involvement in schools has an especially positive

impact on student achievement (Fan & Chen, 2001; Lareau, 2003) and can also lead to improved teacher

morale and empowered parents and communities (National Coalition Ior Parental Involvement in Education,

n.d.).

Throughout courses in pedagogy and practical experience in the Iield, SUNY Cortland`s teacher candidates

examine and discuss the impact oI collaboration with parents, school personnel, the community and other

organizations and agencies on the teaching and learning environment and on student perIormance and

achievement (Laureau, 2003). Further, candidates develop strategies to Ioster positive relationships with

these external constituencies and during their clinical experiences have the opportunity to implement these

2

strategies. The Chancellor`s Action Agenda speciIically requires that candidates` Iield experiences include

collaboration with parents. Both the TEC Advisory Group and partnership schools are currently discussing

additional measures to enrich candidates` understanding oI the importance oI home-school-community

communication and to enhance candidates` opportunities to collaborate.

In addition, candidates must continue to develop professionally as reflective practitioners who are

committed to ongoing scholarly inquiry. Although the term reflective practitioner Iirst appeared in Donald

Schon`s book The Reflective Practitioner (1983), the concept was discussed much earlier and indeed, the

idea oI proIessional reIlection appeared in the works oI John Dewey (1916; 1938). Darling Hammond (1993)

cites the contemporary vision oI Dewey`s work which is applicable even today: 'With the addition oI a Iew

computers, John Dewey`s vision oI the twentieth-century ideal is virtually identical to recent scenarios Ior 21st

century schools (p. 755).

Technical skills, knowledge, behavior and ethical and political judgments are critical components oI reIlective

thought and eIIective teaching (Zeichner & Liston, 1996). As such, the reIlective practitioner (Schon, 1983)

keeps abreast oI current research and technology in the Iield as an aspect oI proIessional development. The

reIlective practitioner is constantly reading, researching, analyzing and questioning issues in the proIession

(Berliner & Biddle, 1995), (Ayers, et al., 2010). SUNY Cortland`s teacher education programs regard

reIlection as a liIelong process Ior educators. As part oI the reIlective process, public school teachers and

college Iaculty should collaborate to design eIIective and up-to-date curriculum Ior teacher education

programs (Goodlad, 1990; Darling-Hammond, 2006).

Similar collaboration may result in the joint advocacy toward additional Iunding to promote eIIective teacher

education programs. SUNY Cortland collaborates with teachers and district administrators through the

Teacher Education Council Advisory Group, individual teacher membership on Teacher Education Council

subcommittees, the Cortland City ProIessional Development School initiative, the Regional ProIessional

Development School initiative, and through collaboration on grants.

Finally, proIessional development Irom pre-service teacher preparation through in-service proIessional

development can be traced through implementation oI a proIessional portIolio. Campbell, Cignette,

Melenyzer, Nettles & Wyman (2001) suggest that portIolios be organized according to INTASC Standards,

with artiIacts and documentation provided Ior each standard. Kaplan and EdIelt (1996) also advocate Ior

implementation oI the INTASC Standards: 'The complexity oI the principles suggests that learning to teach

requires a coherent, developmental process Iocused on integrating knowing and doing, with critical reIlection

as an inherent practice (p. 26). The process oI teacher candidate development can be viewed clearly via

portIolio review. All teacher candidate portIolios at SUNY Cortland contain reIlective work; discussion is

underway within programs and in the Teacher Education Council regarding Iormatting oI portIolios to the

INTASC Standards. Some programs have initiated portIolio development through use oI TaskStream as a

means oI monitoring and assessing candidate development.

,D=6;=@;>

Our candidates integrate curriculum among disciplines and balance historical and contemporary

research, theory, and practice. In considering curriculum integration, outside the classroom one does not

typically encounter problems rooted in a single discipline, but rather one is more oIten conIronted with the

need to solve problems using inIormation associated with a variety oI approaches. Similarly, when learning is

perceived as disconnected Irom a meaningIul context, students` Iull engagement in the process is minimized.

As such, candidates` ability to help students make these connections, across disciplinary boundaries or Irom

what is learned in the classroom to the real world is a hallmark oI eIIective teaching. It Iollows that in order

Ior teacher candidates to help students make these connections, they must be able to see the connections

themselves and develop and implement curricula that link knowledge across various areas oI study (Bellanca

& Brandt, 2010).

3

There is much support in the literature Ior an integrated curriculum (Marzano & Brown, 2009), which is

deIined by Shoemaker (1989): '. education that is organized in such a way that it cuts across subject

matter lines, bringing together various aspects oI the curriculum into meaningIul association to Iocus upon

broad areas oI study. It views learning and teaching in a holistic way and reIlects the real world, which is

interactive (p. 5). Drake (1998) devotes an entire volume to research that demonstrates the many beneIits oI

this educational approach, including increases in learning, motivation Ior learning, and the ability to apply

concepts and utilize higher-order thinking, as well as decreases in math anxiety and disruptive behavior.

Candidates` understanding oI the social, historical and philosophical context oI education inIorms their critical

analysis oI existing theory and practice. (Wiggins & McTighe, 1998; Trilling & Fadel, 2009). During courses

in pedagogy, SUNY Cortland teacher candidates review and discuss state and national standards appropriate to

the content and developmental level oI their certiIicate. Candidates examine curricular guides and design and

implement lesson plans and units that integrate knowledge across disciplines, relate to real liIe, and align with

the standards. Candidates` implementation oI lesson plans with classroom students during Iield

experience or student teaching is monitored and evaluated by the cooperating teacher, instructors and college

supervisors. Candidates reIlect on their work and select representative samples oI their most eIIective

curriculum design and lesson planning Ior inclusion in their proIessional portIolio.

With respect to balancing historical and contemporary research, theory, and practice, John Dewey observed

that educational history was as relevant in 1916 as in the past in addressing existing problems and issues in

education (1916). The observation continues to be signiIicant today. II teacher candidates are to be successIul

in educating the next generation, they must appreciate the work oI pioneers in education on whose work we

build and Irom whom we gain insight into the complex world oI teaching and learning. However, quality

preparation oI teacher candidates also requires a willingness to evaluate existing theories and knowledge on

an ongoing basis, making revisions as necessary, as revealed through sound empirical methods. Related to this

notion is the Iact that no knowledge is 'neutral since it inherently reIlects the socio-cultural context in which

it emerges, as well as the values and socialization oI the researchers who generated it (Banks, 1999; Oakes,

Rogers and Lipton, 2006). SUNY Cortland`s teacher education programs strive to produce candidates who

evince this kind oI 'healthy skepticism when evaluating research inIormation on curriculum, instruction and

educational practice in general.

In addition, all teacher education programs at SUNY Cortland require either a Foundations oI Education

course or inIusion oI educational Ioundations instruction in methods courses. Each program includes critical

review and discussion oI educational trends Irom early research to the present, and best practices in education

are discussed in methods course and implemented during practical experiences and student teaching.

As a second outcome included in SUNY Cortland`s Standards 'branch, candidates must demonstrate good

moral character. Movement toward character education in the nation`s schools has been in motion Ior

some time and is extremely strong at present. As discussed earlier, SUNY Cortland aspires to be a college oI

character, and it is our intention that candidates learn to educate Ior character as well as Ior intellect. They

embody the highest ethical standards in establishing and maintaining a psychologically and socially saIe,

respectIul and supportive environment oIIering stability, security, aIIirmation, acceptance, connections to

community, and access to basic resources so that all children can learn (Noddings, 2002; Charney, 2002).

SUNY Cortland teacher education programs expose candidates to the various concepts, ideas and strategies

developed by leading researchers in the Iield oI character education, with special emphasis placed on teaching

strategies that are eIIective in implementing a comprehensive character education program (Lickona, 1991;

Kohn, 1997).

Teacher candidates at SUNY Cortland demonstrate good moral character in multiple ways, Iirst by selI-

reporting on the Application to Teacher Education. SUNY Cortland reviews candidate dispositions as well.

Judicial screenings are conducted by the Judicial AIIairs oIIice prior to acceptance into the program and at the

4

point oI eligibility to student teach. Candidates are expected to demonstrate proIessional ethics throughout the

100 hours oI Iieldwork and the student teaching experience. Cooperating teacher, instructors and supervisors

discuss any problems in this area directly with the teacher candidate at Iormal and inIormal meetings,

observation debrieIings or during the three-way discussion oI the student teaching evaluation.

New York State requires Iingerprinting Ior certiIication and two background checks, one by the Criminal

Justice Department and one by the FBI. All teacher candidates Iile Iingerprints with the NYSED and

increasing numbers oI school districts are requiring Iingerprinting beIore placing practicum or student

teaching candidates.

'BE:@>BDF

Candidate Learning Outcomes 10 and 11 state that 'Candidates will apply a variety oI teaching strategies to

develop a positive teaching-learning environment where all students are encouraged to achieve their highest

potential and 'Candidates will Ioster understanding oI and respect Ior individual`s abilities, disabilities and

diversity oI variations in ethnicity, culture, language, gender, age, class, and sexual orientation. EIIective

teachers must assure that all students can learn, through use oI a variety oI teaching strategies that address

the individual needs oI students in both academic and social areas (Grossman, 2004). The need Ior multiple

teaching strategies has been acknowledged consistently throughout the literature, evident Irom Bruner (1960)

to the present day. As observed by Bruner, 'In sum, then, the teacher`s task as communicator, model, and

identiIication Iigure can be supported by a wise use oI a variety oI devices that expand experience, clariIy it,

and give it personal signiIicance (p. 91). Candidates are encouraged to recognize the range oI diversity and

to diIIerentiate planning and implementing lessons to address diversity, including application oI Gardner`s

theory oI multiple intelligences (1983), which distinguished among diIIerent types oI learners and suggested

ways to teach each eIIectively. Knowledge and ability to teach in an inclusive setting has become increasingly

important, as has the ability oI the teacher to manage classrooms with students Irom diIIering socioeconomic

backgrounds, diverse populations and Irom homes where the native language is not English. Collaborative,

student-centered classrooms have long been considered a useIul Iorum Ior learning (Goodlad, 1984, Grubb

& Tredway, 2010). At SUNY Cortland all teacher candidates receive training and experience in the use oI

multiple teaching strategies, collaborative learning, inclusive settings, and literacy. Candidates also engage in

100 hours oI pre-student teaching as well as student teaching experiences in a variety oI school settings and

with diverse student populations where their training is put into practice.

As a second outcome related to Diversitv, our candidates must foster respect for individual`s

abilities and disabilities and an understanding and appreciation of variations of ethnicity,

culture, language, gender, age, class, and sexual orientation. Just as educators must

understand the similarities that characterize children`s learning and development, they must

recognize the many ways children diIIer Irom each other and how these diIIerences can inIluence

teaching and learning (Grossman, 2004; Delpit, 2006). In addition, it is increasingly important in our

multicultural society that educators transcend simple knowledge and 'tolerance oI diIIerences among

humans, and in Iact appreciate and respect those diIIerences. Such attitudes are necessary in part because

they help ensure that children have an optimal learning experience regardless oI their background and other

characteristics. They are also necessary because educators have a critical modeling eIIect on children, many oI

whom respond aversively to any kind oI diIIerence in others. As such it is important Ior children to sense and

see that their teachers view individual variations in a positive Iashion (Grubb & Tredway, 2010).

In the past decade Iew issues in the Iield oI education have generated more attention than this

one, with much oI the relevant literature Ialling under the umbrella oI 'multicultural education

(e.g., Banks, 1999; Gay, 1994; Nieto, 2000). More modern authors, however, owe a great debt

to anthropologist John Ogbu (1974; 1978) who was one oI the Iirst to attempt to tease out the

contributions oI racial/ethnic status, culture, and social class in explaining why American public

education was 'Iailing poor ethnic minority children, especially blacks and Hispanics. Thirty

years aIter Ogbu`s initial writings, public education continues to Iace the same challenges he

5

described in the 1970`s. These challenges include: ongoing diIIerences in children`s school

achievement based on their ethnic status and social class (Gay, 1994), the occurrence oI 'cultural

clashes between the school and a student`s home and community (Banks, 1999; Delpit, 2006),

and the tendency Ior teachers to respond to children on the basis oI stereotypes the teachers hold

regarding the child`s race/ethnicity and social class (Delpit, 2006). More positively, a signiIicant

number oI recommendations have also emerged Ior overcoming these challenges (e.g., Delpit,

2006; Grossman, 2004; Nieto, 2000).

The No Child Left Behind Act (2002) includes provisions Ior taking these variations into account. As an

example, annual progress toward standards Ior each state, school district, and school is measured by sorting

test results Ior students who are economically disadvantaged, are Irom racial or ethnic minority groups, have

disabilities, or have limited proIiciency in English. Results are also sorted by gender and migrant status.

Since these results must be included in state and district annual reports, any 'achievement gaps between

particular student groups are clear and public, with the intent that these gaps can be closed through appropriate

intervention.

It is also notable that the NCLB Act addresses the special needs oI children who are giIted and talented.

Finally, although early 'multicultural education initiatives Iocused exclusively on race and ethnicity,

more recently there has been growing recognition oI other Iactors that contribute to children`s 'diIIerence,

including social class, disability status linguistic variations and sexual orientation (e.g., Delpit, 2006;

Grossman, 2004 ; Mercer & Mercer, 1998; and Nieto, 2000).

SUNY Cortland exposes candidates to the origins and characteristics oI racism, sexism, and other Iorms oI

oppression, at both the individual and institutional levels and in both this country and in a global context as

part oI its General Education Program. The College requires students to take coursework in Prejudice and

Discrimination. In addition, all teacher candidates are required by NYSED to complete a year oI college-

level study oI a Ioreign language, including awareness oI other cultures as part oI their preparation Ior

teaching a diverse student population. A web-based interactive ESL module developed to enhance candidates`

understanding oI diIIerent cultures is currently being redesigned to more eIIectively address teacher

candidates` understanding and response to students whose home language is not English.

.:GH6797<F

Our candidates must demonstrate sufficient technology skills and the ability to integrate

technology into classroom teaching/learning. Access to computers, the internet and e-mail has

exponentially increased since the last NCATE Accreditation visit. Lower-cost technology has narrowed

the gap between those who have computer access and services and those who do not, making them more

accessible to those Irom lower income Iamilies and poorer school districts; digital inIusion has become a

realizable goal.

The impact oI technology and computers on learning and development has been consistently substantiated

(Papert, 1980), but eIIective computer instruction requires thoughtIul guidance by educators is a challenge

(Trilling, B. & Fadel, C. (2009). Instruction in this area must Iacilitate critical thinking and higher-order

learning, helping students understand historical perspectives oI technology and science as they interact with

cultural developments in order to understand their eventual impact on culture and the environment (Floden

& Ashburn, 2006). New and eIIective learning and teaching approaches will continue to be a key Iocus

Ior educators; candidates must know how and when to use computers, how to understand their potential in

enhancing learning, and how to integrate computers and technology most eIIectively and appropriately into the

curriculum (Ribble & Bailey, 2007).

SUNY Cortland has a number oI requirements in place to ensure students` technology competence. All SUNY

Cortland students complete two writing intensive courses Ior graduation, one oI which must be in the major.

6

Writing intensive (WI) courses require that students use technology Ior research in preparation oI writing

a 25-30 page term paper. This requirement typically represents the Iirst step that teacher candidates take to

demonstrate their inIormation technology general skills. Sixty-Iive technology classrooms on campus at

present provide access to instruction in technology as well as demonstration oI expertise. Technology support

is available to Iaculty and candidates through workshops and individual attention online or at a Help Desk

in Memorial Library. Candidates have access to computers, computer based inIormation systems, soItware

applications, computer hardware, and inIormation databases. There are two video-conIerencing Iacilities and

some portable systems available Ior Iaculty use. The technology has been used Ior video conIerencing in a

variety oI areas such as communication with partner schools in Australia where teacher education candidates

complete one student teaching experience, and between teacher education classes and partner schools where in

service teachers demonstrate planning strategies, and implementation oI lessons. Technology is also available

to allow real-time observation oI classes in the SUNY Cortland Childcare Center.

Methodology courses serve as the main source Ior IulIillment oI technology perIormance outcomes in the

content area. Candidates must demonstrate use oI technology in lesson planning, unit planning and classroom

presentations. For example, candidates demonstrate integration oI presentation soItware, development oI

web-based resources and the use oI classroom management soItware. Prior to student teaching, candidates

receive training in identiIication and implementation oI appropriate soItware Ior teaching in the Iield. Student

Teaching candidates are expected to demonstrate use oI appropriate technology in classroom instruction

and are evaluated by the cooperating teacher and the College supervisor. Some teacher education programs

have moved to the use oI electronic portIolios. The TEC has identiIied TaskStream as a program that will be

essential in Iacilitating two-way communication between programs and the unit. An electronic portIolio model

is currently used in the Thematic Methods Block Ior the Childhood Education Program.

/:A:@:6G:>

Apple, M. (2004). Ideologv and Curriculum (3rd ed.). New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

Ayers, W., Kumashiro, K., Meiners, E., Quinn, T., & Stovall, D. (2010). Teaching Toward Democracv.

Educators as Agents of Change. Boulder, London: Paradigm Publishers.

Banks, J. A. (1999). The lives and values oI researchers: Implications Ior educating citizens in a multicultural

world. Educational Researcher, 27(7), 4-17.

Bellanca, J. & Brandt, R. (Eds.). (2010). 21st Century Skills: Rethinking How Students Learn. Bloomington,

IN: Solution Tree Publishers"

Berliner, D. C. & Biddle, J. (1995). The Manufactured Crisis, Mvths, Fraud, and the Attack on Americas

Public Schools. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Bruner, J.S. (1960). The Process of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Butchart, R. & McEwan, B. (Eds.). (1998). Classroom Discipline in American Schools: Problems and

Possibilities Ior Democratic Education. Albany, NY: State University oI New York Press.

Campbell, D.M., Cignette, P.B., Melenyzer, B.J., Nettles, D.H., & Wyman, R.M. (2001). How to Develop a

Professional Portfolio. A Manual for Teachers. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Charney, R. S. Teaching Children to Care. Classroom Management for Ethical and Academic Growth, K-8.

Turners Falls, MA: Northeast Foundation Ior Children.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1993). ReIraming the school reIorm agenda: Developing capacity Ior school

transIormation. Phi Delta Kappan, 74(10), 753-761.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1998). Teacher learning that supports student learning. Educational Leadership 55 (5),

6-11.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Powerful Teacher Education. Lessons from Exemplarv Programs. San

Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Darling-Hammond, L. & Youngs, P. (2002). DeIining 'highly qualiIied teachers: What does 'scientiIically-

based research actually tell us? Educational Researcher, 31(9), 13-25.

Delpit, L. (2006). Other Peoples Children. Cultural Conflict in the Classroom. New York: The New Press.

7

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracv and Education. New York: Free Press.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan. #$

Drake, S. M. (1998). Creating Integrated Curriculum. Proven Wavs to Increase Student Learning. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Fan, X. & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students` academic achievement: A meta-analysis.

Educational Psvchologv Review, 13(1): 1-22.

Floden, R.E. & Ashburn, E. A. (2006). Meaningful Learning Using Technologv. What Educators Need to

Know and Do. New York: Teachers College Press.

Gardner, H. (1993). Frames of Mind. The Theorv of Multiple Intelligences (2nd ed.). New York: BasicBooks.

Gay, G. (1994). At the Essence of Learning. Multicultural Education. West LaIayette, IN: Kappa Delta Pi.

Goodlad, J. I. (1990). Teachers for Our Nations Schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Grossman, H. G. (2004). Classroom Behavior Management for Diverse and Inclusive Schools. (3rd ed.).

Lanham, MD. Rowan & LittleIield.

Grubb, W. N. & Tredway, (2010). Leading From the Inside Out. Expanded Roles for Teachers in Equitable

Schools. Boulder, London: Paradigm Publishers.

Kaplan, L. & EdelIelt, R.A. (Eds.). (1996). Teachers for the New Millennium. Aligning Teacher Development,

National Goals and High Standards for All Students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc.

Kohn, A. (1997). How not to teach values. Phi Delta Kappan, 78 (5), 428.

Kozol, J. (1991). Savage Inequalities. Children in Americas Schools. New York: Crown Publishers.

Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal Childhoods. Race, Class and Familv Life. Berkely, CA: University oI CaliIornia

Press.

Lickona, T. (1991). Educating for Character. How Schools can Teach Respect and Responsibilitv. New York:

Bantam Books.

Marzano, R. J. with Jana S. Marzano and Debra J. Pickering (2009). Classroom Management that Works.

Research-Based Strategies for Everv Teacher. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Marzano, R. J. & Brown, J. L. (2009) A Handbook Ior the Art and Science oI Teaching. Alexandria, VA.

Association Ior Supervision and Curriculum Development. ##

Mercer, C.D., & Mercer, A.R. (1998). Teaching Students with Learning Problems. Upper Saddle Ridge, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

National Coalition Ior Parental Involvement in Education. (n.d.). Retrieved Irom http://www.ncpie.org.

New York State Education Department (1998). Teaching to Higher Standards. New Yorks Commitment.

Albany, NY: New York State Education Department.

Nieto, S. & Bode, P. (2008). Affirming Diversitv. The Sociopolitical Context of Multicultural Education (5th

ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Noddings, N. (2002). Educating Moral People. A Caring Alternative to Character Education. New York:

Teachers College Press.

Oakes, J., Rogers, J. & Lipton, M. (2006) Learning Power; Organizin Ior Education and Justice. New York:

Teachers College Press.

Ogbu, J. U. (1978). Minoritv Education and Caste. The American Svstem in Cross-cultural Perspective. New

York: Academic Press.

Ogbu, J. U. (1974). The Next Generation. An Ethnographv of Education in an Urban Neighborhood. New

York: Academic Press.

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms. Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. New York: Basic Books.

Piaget, J. (1970). Science of Education and the Psvchologv of the Child. New York: Orion Press.

Ribble, M., & Bailey, G. D. (2007). Digital Citi:enship in Schools. Washington, DC: International Society Ior

Technology Education.

Shoemaker, B. (1989). Integrative education: A curriculum Ior the twenty-Iirst century. Oregon School Studv

Council, 33(2).

State University oI New York College at Cortland (2009). Vision Statement. http://www2.cortland.edu/

committees/strategic-planning-steering-committee/vision-statement.dot.

8

State University oI New York System Administration. (2001). A New Jision in Teacher Education. Agenda

for Change in SUNYs Teacher Preparation Programs. Retrieved Irom http://www.suny.edu/sunypp/

documents.cIm?docid191. #%

Trilling, B. & Fadel, C. (2009). 21st Centurv Skills. Learning for Life in Our Times. Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley

& Sons.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in Societv. The Development of Higher Psvchological Processes. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding bv Design. Alexandria, VA: Association Ior Supervision

and Curriculum Development.

Zeichner, K. & Liston, D. (1996). Reflective Teaching. New York: Erlbaum Publishers

9

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Connecting Readers to Multiple Perspectives: Using Culturally Relevant Pedagogy in a Multicultural ClassroomDa EverandConnecting Readers to Multiple Perspectives: Using Culturally Relevant Pedagogy in a Multicultural ClassroomNessuna valutazione finora

- The Power of Education: Education and LearningDa EverandThe Power of Education: Education and LearningNessuna valutazione finora

- Productive Pedagogies: Through The Lens of Mathematics Education Graduate StudentsDocumento13 pagineProductive Pedagogies: Through The Lens of Mathematics Education Graduate StudentsZita DalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Fronda - Adriel Dofel - Notes - ReadingDocumento7 pagineFronda - Adriel Dofel - Notes - ReadingADRIEL FRONDANessuna valutazione finora

- NCCTE Highlight05-ContextualTeachingLearningDocumento8 pagineNCCTE Highlight05-ContextualTeachingLearningpindungNessuna valutazione finora

- Content ServerDocumento25 pagineContent ServersyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Citizenship Education and The Development of Globally Competent - Michael A Kopish - 2017Documento40 pagineGlobal Citizenship Education and The Development of Globally Competent - Michael A Kopish - 2017Aprilasmaria SihotangNessuna valutazione finora

- Article 26258 PDFDocumento12 pagineArticle 26258 PDFsanjay_vanyNessuna valutazione finora

- Development and Validation of Creative Works As Supplementary Instructional Materials in Home Economics and Livelihood Education (Hele)Documento14 pagineDevelopment and Validation of Creative Works As Supplementary Instructional Materials in Home Economics and Livelihood Education (Hele)Lenneymae MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Local Media5766598185496389114Documento7 pagineLocal Media5766598185496389114Zoey LedesmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Institutional RepositoryDocumento8 pagineFaculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Institutional RepositoryNori Jayne Cosa RubisNessuna valutazione finora

- PR2 Research Chapter 2Documento10 paginePR2 Research Chapter 2Gabriel Jr. reyesNessuna valutazione finora

- Course of Study Template UpdatedDocumento8 pagineCourse of Study Template UpdatedAdam MikitzelNessuna valutazione finora

- Role As Teacher in Developing Sustainable DevelopmentDocumento7 pagineRole As Teacher in Developing Sustainable DevelopmentNayab Amjad Nayab AmjadNessuna valutazione finora

- Phenomenological Study 2 1Documento12 paginePhenomenological Study 2 1rashmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Pedzisai and Shava - A Model For The Effective Inclusion of Indigenous Agricultural Knowledge and Practices in A School Agriculture CurriculumDocumento10 paginePedzisai and Shava - A Model For The Effective Inclusion of Indigenous Agricultural Knowledge and Practices in A School Agriculture CurriculumchazunguzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophy Refllection 3Documento3 paginePhilosophy Refllection 3kimbeerlyn doromasNessuna valutazione finora

- Lategan SC - Philosophy EssayDocumento8 pagineLategan SC - Philosophy EssaySimoneNessuna valutazione finora

- Eds 811 Syllabus 1Documento10 pagineEds 811 Syllabus 1api-203678345Nessuna valutazione finora

- EDN 334 Elementary Social Studies Curriculum & Instruction (K-6) Section 003 University of North Carolina at Wilmington Watson School of EducationDocumento8 pagineEDN 334 Elementary Social Studies Curriculum & Instruction (K-6) Section 003 University of North Carolina at Wilmington Watson School of EducationPatrick Philip BalletaNessuna valutazione finora

- Book ChapterDocumento35 pagineBook ChapterAhmed SalihuNessuna valutazione finora

- Reflective Learning in Higher Education Active MetDocumento8 pagineReflective Learning in Higher Education Active Metmagi14Nessuna valutazione finora

- Teacher Education For Primary StageDocumento78 pagineTeacher Education For Primary Stageidealparrot100% (1)

- Best Practices in Canadian EducationDocumento10 pagineBest Practices in Canadian EducationjoannNessuna valutazione finora

- Pec 103Documento6 paginePec 103Justine Ramirez100% (2)

- Curriculum InnovationsDocumento7 pagineCurriculum InnovationsAngelo LabadorNessuna valutazione finora

- The Importance of Educational ResourcesDocumento14 pagineThe Importance of Educational ResourcesHenzbely JudeNessuna valutazione finora

- Equity Pedagogy An Essential Component of Multicultural EducationDocumento8 pagineEquity Pedagogy An Essential Component of Multicultural Educationintanmeitriyani sekolahyahyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Artifact 4Documento46 pagineArtifact 4api-418324429Nessuna valutazione finora

- Humanising Pedagogies Andre KeetDocumento13 pagineHumanising Pedagogies Andre Keetgar2toneNessuna valutazione finora

- 21st Century Standards and CurriculumDocumento3 pagine21st Century Standards and CurriculumMae SandiganNessuna valutazione finora

- R Wilman 17325509 Assessment 1Documento7 pagineR Wilman 17325509 Assessment 1api-314401095Nessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculuminnovations 140202033422 Phpapp01Documento57 pagineCurriculuminnovations 140202033422 Phpapp01Mary Joy RobisNessuna valutazione finora

- Emh442 11501113 2 1Documento9 pagineEmh442 11501113 2 1api-326968990Nessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation Tool For The Application Discovery Teaching Method in The Greek Environmental School ProjectsDocumento12 pagineEvaluation Tool For The Application Discovery Teaching Method in The Greek Environmental School ProjectsWardahNessuna valutazione finora

- Integration of Teaching Practice For Students' 21st Century Skills: Faculty Practice and PerceptionDocumento24 pagineIntegration of Teaching Practice For Students' 21st Century Skills: Faculty Practice and PerceptionjohnNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 7 The TeacherDocumento13 pagineChapter 7 The TeacherErick JohnNessuna valutazione finora

- Student Teachers' Ways To Integrate Character Values in EFL ClassroomDocumento6 pagineStudent Teachers' Ways To Integrate Character Values in EFL ClassroomashambjNessuna valutazione finora

- Nurul Hikmah RamadhaniDocumento3 pagineNurul Hikmah RamadhaniAnjasmara RheostatNessuna valutazione finora

- Education SystemDocumento2 pagineEducation SystemikkinenganioNessuna valutazione finora

- Facilty Members Who Engage in Inclusiva Pedagogy Methodological and Affective Strategies For TeachingDocumento17 pagineFacilty Members Who Engage in Inclusiva Pedagogy Methodological and Affective Strategies For TeachingfonoximenaaguirreNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter IiDocumento36 pagineChapter IiMichael Casil MillanesNessuna valutazione finora

- Critical Reflection9Documento4 pagineCritical Reflection9api-357627068Nessuna valutazione finora

- Students Affairs With UrduDocumento6 pagineStudents Affairs With UrduTariq Ghayyur100% (1)

- Full Thesis RevisionDocumento19 pagineFull Thesis RevisionChristian Marc Colobong PalmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Resume English Curriculum DevelopmentDocumento7 pagineResume English Curriculum Developmentlisthia izzatyNessuna valutazione finora

- A Brief Note On National Curriculum Fram PDFDocumento7 pagineA Brief Note On National Curriculum Fram PDFvinay sharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- 6421 14773 1 SMDocumento14 pagine6421 14773 1 SMAl Patrick ChavitNessuna valutazione finora

- Teachers' Perceptions of Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and The Impact On Leadership Preparation: Lessons For Future Reform EffortsDocumento20 pagineTeachers' Perceptions of Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and The Impact On Leadership Preparation: Lessons For Future Reform EffortsKhemHuangNessuna valutazione finora

- A New Teaching Method For Teaching Economics in Secondary EducationDocumento8 pagineA New Teaching Method For Teaching Economics in Secondary EducationPrachi DagaNessuna valutazione finora

- 8612 Solve Assignment No 2Documento11 pagine8612 Solve Assignment No 2Pcr LabNessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum ReformDocumento4 pagineCurriculum ReformvaibhavNessuna valutazione finora

- Formative Assessment Techniques Tutors Use To Assess Teacher-Trainees' Learning in Social Studies in Colleges of Education in GhanaDocumento12 pagineFormative Assessment Techniques Tutors Use To Assess Teacher-Trainees' Learning in Social Studies in Colleges of Education in GhanaAlexander DeckerNessuna valutazione finora

- Role of Teacher's in Curriculum Construction and Transaction - Search For Better FutureDocumento10 pagineRole of Teacher's in Curriculum Construction and Transaction - Search For Better FutureAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNessuna valutazione finora

- Project-Based Learning and The Acquisition of Competencies and Knowledge Transfer in Higher EducationDocumento18 pagineProject-Based Learning and The Acquisition of Competencies and Knowledge Transfer in Higher EducationLAILANIE DELA PENANessuna valutazione finora

- 21st Century (1) AssignmentDocumento7 pagine21st Century (1) AssignmentSuresh SainathNessuna valutazione finora

- A Comparison of Preferred Learning Styles Between Vocational and Academic Secondary School Students in EgyptDocumento9 pagineA Comparison of Preferred Learning Styles Between Vocational and Academic Secondary School Students in EgyptSha' RinNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching First YearsDocumento7 pagineTeaching First YearsAda CabreNessuna valutazione finora

- Using Cutting-Edge Technology: Tools to Consider for Enhancing Learning In Grades Six through TwelveDa EverandUsing Cutting-Edge Technology: Tools to Consider for Enhancing Learning In Grades Six through TwelveNessuna valutazione finora

- Multicultural Education Training: The Key to Effectively Training Our TeachersDa EverandMulticultural Education Training: The Key to Effectively Training Our TeachersNessuna valutazione finora

- Non-Fiction Writing SampleDocumento6 pagineNon-Fiction Writing Samplemadison.giannattasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Persuasive Writing SampleDocumento6 paginePersuasive Writing Samplemadison.giannattasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Non-Fiction Writing SampleDocumento6 pagineNon-Fiction Writing Samplemadison.giannattasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Madison GiannattasioDocumento1 paginaMadison Giannattasiomadison.giannattasiNessuna valutazione finora

- "What's in A Tone?" Instructor GuideDocumento3 pagine"What's in A Tone?" Instructor Guidemadison.giannattasiNessuna valutazione finora

- PIDS Research On Rethinking Digital LiteracyDocumento8 paginePIDS Research On Rethinking Digital LiteracyYasuo Yap NakajimaNessuna valutazione finora

- 90-Minute Literacy Block: By: Erica MckenzieDocumento8 pagine90-Minute Literacy Block: By: Erica Mckenzieapi-337141545Nessuna valutazione finora

- CSC 408 Distributed Information Systems (Spring 23-24)Documento7 pagineCSC 408 Distributed Information Systems (Spring 23-24)Sun ShineNessuna valutazione finora

- Natural and Inverted Order of SentencesDocumento27 pagineNatural and Inverted Order of SentencesMaribie SA Metre33% (3)

- Unit 11 Science Nature Lesson PlanDocumento2 pagineUnit 11 Science Nature Lesson Planapi-590570447Nessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis of Additional Mathematics SPM PapersDocumento2 pagineAnalysis of Additional Mathematics SPM PapersJeremy LingNessuna valutazione finora

- Belfiore, 2008 Rethinking The Social Impact of The Arts: A Critical-Historical ReviewDocumento248 pagineBelfiore, 2008 Rethinking The Social Impact of The Arts: A Critical-Historical ReviewViviana Carolina Jaramillo Alemán100% (1)

- 1 Host - Event RundownDocumento2 pagine1 Host - Event RundownMonica WatunaNessuna valutazione finora

- T04S - Lesson Plan Unit 7 (Day 3)Documento4 pagineT04S - Lesson Plan Unit 7 (Day 3)9csnfkw6wwNessuna valutazione finora

- Exam Topics Part IDocumento31 pagineExam Topics Part ISylviNessuna valutazione finora

- Error Analysis Practice Form 6Documento3 pagineError Analysis Practice Form 6manbitt1208Nessuna valutazione finora

- Implementation of Intrusion Detection Using Backpropagation AlgorithmDocumento5 pagineImplementation of Intrusion Detection Using Backpropagation Algorithmpurushothaman sinivasanNessuna valutazione finora

- EE2002 Analog Electronics - OBTLDocumento8 pagineEE2002 Analog Electronics - OBTLAaron TanNessuna valutazione finora

- Stuti Jain MbaDocumento65 pagineStuti Jain MbaKookie ShresthaNessuna valutazione finora

- FIITJEE1Documento5 pagineFIITJEE1Raunak RoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Black Bodies White Bodies Gypsy Images IDocumento23 pagineBlack Bodies White Bodies Gypsy Images IPatricia GallettiNessuna valutazione finora

- Khalil's Maailmanvaihto ESC Volunteer ApplicationDocumento6 pagineKhalil's Maailmanvaihto ESC Volunteer Applicationpour georgeNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Stages of Design ThinkingDocumento59 pagine5 Stages of Design ThinkingsampathsamudralaNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Speak Fluent EnglishDocumento7 pagineHow To Speak Fluent Englishdfcraniac5956Nessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Communication in Context 2 Quarter ExamDocumento3 pagineOral Communication in Context 2 Quarter ExamCleo DehinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Short CV: Prof. Dr. Zulkardi, M.I.Komp., MSCDocumento39 pagineShort CV: Prof. Dr. Zulkardi, M.I.Komp., MSCDika Dani SeptiatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Region Province Reference Number Learner IDDocumento10 pagineRegion Province Reference Number Learner IDLloydie LopezNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Reading Verification SheetDocumento2 pagineOral Reading Verification SheetMark James VallejosNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan ForgeryDocumento1 paginaLesson Plan Forgeryapi-316826697Nessuna valutazione finora

- Art Appreciation HS HomeschoolDocumento5 pagineArt Appreciation HS HomeschoolRene Jay-ar Morante SegundoNessuna valutazione finora

- Geoarchaeology2012 Abstracts A-LDocumento173 pagineGeoarchaeology2012 Abstracts A-LPieroZizzaniaNessuna valutazione finora

- 12 Esl Topics Quiz HealthDocumento2 pagine12 Esl Topics Quiz HealthSiddhartha Shankar NayakNessuna valutazione finora

- Matematik K1,2 Trial PMR 2012 MRSM S PDFDocumento0 pagineMatematik K1,2 Trial PMR 2012 MRSM S PDFLau Xin JieNessuna valutazione finora

- Line Officer Accessions BOT HandbookDocumento88 pagineLine Officer Accessions BOT HandbookamlamarraNessuna valutazione finora

- Michelle Phan Anorexia Nervosa FinalDocumento12 pagineMichelle Phan Anorexia Nervosa Finalapi-298517408Nessuna valutazione finora