Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Links Between Adolescents' Expected Parental Reactions and Prosocial Behavioral Tendencies - The Mediating Role of Prosocial Values - Hardy, Carlo & Roesch (2010)

Caricato da

Eduardo Aguirre Dávila0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

47 visualizzazioni13 pagineStudy examines relations between adolescents' social cognitions regarding parenting practices and adolescents' prosocial behavioral tendencies. Degree to which adolescents perceived their parents as responding appropriately was hypothesized to predict adolescents' tendencies toward prosocial behavior. Findings provide evidence for the central role of adolescents' evaluations and expectancies of parental behaviors.

Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Links Between Adolescents’ Expected Parental Reactions and Prosocial Behavioral Tendencies- The Mediating Role of Prosocial Values - Hardy, Carlo & Roesch (2010)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoStudy examines relations between adolescents' social cognitions regarding parenting practices and adolescents' prosocial behavioral tendencies. Degree to which adolescents perceived their parents as responding appropriately was hypothesized to predict adolescents' tendencies toward prosocial behavior. Findings provide evidence for the central role of adolescents' evaluations and expectancies of parental behaviors.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

47 visualizzazioni13 pagineLinks Between Adolescents' Expected Parental Reactions and Prosocial Behavioral Tendencies - The Mediating Role of Prosocial Values - Hardy, Carlo & Roesch (2010)

Caricato da

Eduardo Aguirre DávilaStudy examines relations between adolescents' social cognitions regarding parenting practices and adolescents' prosocial behavioral tendencies. Degree to which adolescents perceived their parents as responding appropriately was hypothesized to predict adolescents' tendencies toward prosocial behavior. Findings provide evidence for the central role of adolescents' evaluations and expectancies of parental behaviors.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 13

EMPI RI CAL RESEARCH

Links Between Adolescents Expected Parental Reactions

and Prosocial Behavioral Tendencies: The Mediating Role

of Prosocial Values

Sam A. Hardy Gustavo Carlo Scott C. Roesch

Received: 23 September 2008 / Accepted: 19 December 2008 / Published online: 7 January 2009

Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2009

Abstract The purpose of the present study was to

examine relations between adolescents social cognitions

regarding parenting practices and adolescents prosocial

behavioral tendencies. A mediation model was tested

whereby the degree to which adolescents perceived their

parents as responding appropriately to their prosocial and

antisocial behaviors was hypothesized to predict adoles-

cents tendencies toward prosocial behavior indirectly

by way of adolescents prosocial values. Adolescents

(N = 140; M age = 16.76 years, SD = .80; 64% girls;

91% European Americans) completed measures of proso-

cial values and of the appropriateness with which they

expected their parents to react to their prosocial and anti-

social behaviors. In addition, teachers and parents rated the

adolescents tendencies for prosocial behaviors. A struc-

tural equation model test showed that the degree to which

adolescents expected their parents to respond appropriately

to their prosocial behaviors was related positively to their

prosocial values, which in turn was positively associated

with their tendencies to engage in prosocial behaviors (as

reported by parents and teachers). The ndings provide

evidence for the central role of adolescents evaluations

and expectancies of parental behaviors and of the role of

values in predicting prosocial tendencies. Discussion

focuses on the implications for moral socialization theories

and on the practical implications of these ndings in

understanding adolescents prosocial development.

Keywords Parenting Social cognition

Prosocial behavior Values

Introduction

Much theory and evidence supports the everyday notion

that parents are a key inuence on the prosocial behavior

and development of children and adolescents (Baumrind

1991; Eisenberg and Valiente 2002; Grusec 2006;

Maccoby and Martin 1983). Although some moral devel-

opment theorists such as Kohlberg (1969) sought to

de-emphasize the role of parental socialization, others have

argued for the importance and uniqueness of the parent

child relationship in prosocial and moral development

(Bandura 1986; Eisenberg and Valiente 2002; Grusec

2006; Hoffman 2000). However, we know relatively little

about the mediating mechanisms by which parenting and

parentchild relationships affect prosocial behaviors,

especially in adolescence (Carlo et al. 1999; Eisenberg and

Valiente 2002). In addition to parents behaviors, and the

characteristics of the parentchild relationship, adoles-

cents social cognitions seem to play an important role

(Grusec and Goodnow 1994; Nelson and Crick 1999;

Wyatt and Carlo 2002; Padilla-Walker and Carlo 2004,

2006). Social cognitive theory posits that anticipated con-

sequences of future actions inuence the motivation for

such actions (Bandura 1986). Further, anticipated success

or failure at a given course of action leads to more or less

valuing of that action (Eccles and Wigeld 2002).

S. A. Hardy (&)

Department of Psychology, Brigham Young University, Provo,

UT, USA

e-mail: sam_hardy@byu.edu

G. Carlo

Department of Psychology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln,

Lincoln, NE, USA

S. C. Roesch

Department of Psychology, San Diego State University,

San Diego, CA, USA

1 3

J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495

DOI 10.1007/s10964-008-9383-7

Of particular interest in the present study was the conse-

quences or reactions adolescents expect from their parents

following prosocial and antisocial action, and the relation

of these expected parental reactions to prosocial values and

behaviors. More specically, this study tested a model

whereby adolescents expected parental reactions to pro-

social and antisocial behavior predicted adolescents

prosocial behavioral tendencies indirectly by way of ado-

lescents prosocial values.

Expected Parental Reactions

According to social cognitive theory, consequences inu-

ence antecedent behaviors by creating expectations that, in

the future, acting in similar ways will produce similar out-

comes (Bandura 1986). Specically, anticipated rewards

will increase the likelihood of a particular behavior, while

anticipated punishments will decrease the likelihood of the

behavior. Thus, as opposed to behaviorism, social cognitive

theory posits that responses do not automatically follow

from stimuli, but mediational cognitive processes are

involved. In support of this, research based on social

information-processing theory suggests that children and

adolescents mentally generate possible consequences of

their antisocial (Crick and Dodge 1994) and prosocial

(Nelson and Crick 1999) actions in the process of making

behavioral decisions. Hence, for example, parenting

behaviors do not automatically elicit responses from ado-

lescents, but rather adolescents have social cognitions that

mediate relations between their parents behaviors and their

own actions.

Parents issue many consequences for their adolescents

behaviors, and these parental reactions are evaluated by

adolescents and may play an important role in behavioral

decisions (Wyatt and Carlo 2002; Padilla-Walker and

Carlo 2004, 2006, 2007). For example, when reecting

back on their parents reactions to situations in the past

where they (the adolescents) have acted antisocially (e.g.,

lied), teens tend to see yelling (e.g., He freaked out and

yelled at me!) as less appropriate than talking (e.g., She

sat me down and talked to me about what I had done and

how to x it) as a parental reaction (Padilla-Walker and

Carlo 2004). Similarly, teens see verbal praise (e.g., She

congratulated me and gave me a hug.) as a more appro-

priate parental response to prosocial behavior (e.g., helping

someone in need) than simply talking or even yelling (e.g.,

She told me I should be worrying about my problems and

not other peoples; Padilla-Walker and Carlo 2004). Over

time, adolescents develop general expectancies about their

parents reactions to prosocial and antisocial behaviors

(i.e., perceptions of how appropriately their parents will

likely respond) that might affect their own future prosocial

or antisocial behaviors. Such anticipated parental reactions

are predictive of teens behaviors, with more appropriate

expected parental reactions to antisocial behavior being

negatively related to delinquency and aggression, and more

appropriate expected parental reactions to prosocial

behavior being linked positively to prosocial behavior and

negatively to delinquency and aggression (Wyatt and Carlo

2002). Thus, over time adolescents develop general

expectancies about their parents reactions to prosocial and

antisocial behaviors that might affect their own future

prosocial or antisocial behaviors.

Expected Parental Reactions and Adolescents

Internalization of Values

Adolescents expectancies about their parents reactions to

their prosocial and antisocial behaviors may also be linked

to the internalization of parental values. For adolescents to

internalize their parents values they must accurately per-

ceive their parents values and they must accept those

values; this has been both theoretically (Grusec and

Goodnow 1994) and empirically (Padilla-Walker 2007)

demonstrated. Grusec and Goodnow (1994) argue that

expected parental reactions are important to both of these

components of internalization. In terms of accurate per-

ception, adolescents might be more likely to attend to

parental value messages if they attribute positive intentions

to their parents; such perceptions may be based on a history

of their evaluations of the ways in which their parents have

responded to their behaviors. Teens who perceive their

parents as responding appropriately to their prosocial and

antisocial behaviors are more likely to attribute caring

and helping intentions to their parents than inhibiting and

controlling intentions (Padilla-Walker and Carlo 2004).

Further, affectionate parenting (high warmth and respon-

siveness, with low indifferent, indulgent, and autocratic

parenting practices) is predictive of adolescents accurate

perception of parental values. Hence, in positive parent

teen relationships where teens attribute good will to their

parents intentions, teens may be more likely to tune into

parental messages, and this greater attentiveness to parental

messages generally leads to more accurate understanding

of parental values.

Expected parental reactions may play an even more

important role in whether or not adolescents accept their

parents values. There are at least two potential mecha-

nisms involved. First, the acceptance of values is strongly

inuenced by the degree to which the child believes his or

her parents reactions are appropriate to the deed or mis-

deed and that the parents intervention has truth-value and

that due process has been observed (Grusec and

Goodnow 1994, p. 14). By truth-value they mean that if

J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495 85

1 3

adolescents get in trouble for doing something wrong it is

something that they actually didrather than a false

accusation. Due process here is referring to the notion

that the parents use appropriate and tactful procedures and

interactions when responding to their adolescents behav-

iors. In other words, adolescents are more accepting of

parental socialization when they see their parents as deal-

ing fairly with them in response to their positive and

negative behaviors.

The second way in which adolescents expected parental

reactions may be linked to their acceptance of parental

values is by affecting the subjective value that adolescents

place on certain behaviors. Anticipated success or failure at

a given behavior inuences the perceived value of that

behavior (Eccles and Wigeld 2002). Similarly, perceived

expectations for prosocial behavior have been linked to

prosocial goals (i.e., internalized valuing of prosocial

behavior). So, if an adolescent is praised by his or her

parents for behaving prosocially, he or she may come to

see more value in prosocial behavior. On the other hand, if

prosocial behavior goes unrewarded, it may not be seen as

having as much value. Thus, expected parental reactions

convey information about the anticipated success or failure

of the adolescents behaviors, and these expectancies seem

important for how much adolescents value such behaviors

and are motivated to enact them in the future.

The Role of Values in Prosocial Behavior

In line with prior social sciences conceptualizations, values

were dened as (a) concepts or beliefs, (b) about desirable

end states or behaviors, (c) that transcend specic situa-

tions, (d) guide selection or evaluation of behavior and

events, and (e) are ordered by relative importance

(Schwartz and Bilsky 1987, p. 551). More simply, values

convey what is important to us in our lives (Bardi and

Schwartz 2003, p. 1208). Once appropriated into ones

sense of self, values have a motivational dimension that

provides impetus and direction for volitional behaviors

(Manstead 1996; Ryan and Connell 1989; Verplanken and

Holland 2002). This is likely due to value-consistent

behaviors being rewarding and fullling a need for self-

consistency (Bardi and Schwartz 2003). The strength of

relations between social cognitions (such as values) and

behaviors is dependent on the specicity of the social

cognitions and behaviors involved (Ajzen and Fishbein

2005). Thus, prosocial values (such as kindness) should be

expected to have their strongest impact on prosocial

behavior.

Research has demonstrated signicant relations between

values (or similar constructs such as personal norms and

personal goals) and behaviors, including specic links

between prosocial values and prosocial behaviors

(Bardi and Schwartz 2003). Much of this work has been

done with adults. For example, participants who reported

higher salience of prosocial values (e.g., helpful, equality)

donated more to a charitable organization than those who

reported lower salience of these values in an experimental

condition that primed their self concept (Verplanken and

Holland 2002). Similarly, Bardi and Schwartz (2003)

demonstrated correlations between what they categorize as

benevolence values (i.e., dened as values relevant to

preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people

with whom one is in frequent personal contact; p. 1208)

and prosocial behaviors in adults. Research involving

adolescents has also shown links between prosocial values

and prosocial behaviors (e.g., Padilla-Walker 2007; Padil-

la-Walker and Carlo 2007; Pratt et al. 2003).

The Present Study

Much research has examined correlates of various parent-

ing styles and practices (Bornstein 2002). However, we still

know little about mechanisms by which parenting might

inuence adolescent outcomes. Thus, the present study

makes a contribution by examining the role two aspects of

adolescent social cognition might play in linking parenting

to adolescents behaviors: (a) adolescents perceptions of

the appropriateness of their parents reactions to their

prosocial and antisocial behaviors, and (b) adolescents

prosocial values. In the present study, we positioned pro-

social values as a mediator or indirect link between

expected parental reactions and adolescents prosocial

behavior, largely because research on attitudes suggests

domain-specic social cognitions are more strongly linked

to similar domain-specic behaviors (Ajzen and Fishbein

2005).

More specically, the purpose of the present study was

to test a mediation model whereby adolescents expected

parental reactions to prosocial and antisocial behaviors

would be linked to adolescents prosocial behaviors indi-

rectly by way of prosocial values. This model is founded on

social cognitive theory (Bandura 1986) and its implications

for parenting (Grusec and Goodnow 1994). Specically,

over the course of time adolescents learn about prosocial

values and behaviors partly by the way in which their

parents respond to their antisocial and prosocial behaviors.

Prior focus has generally been on the role of parental

responses to negative child behaviors, so, we sought to also

examine the role of parental responses to positive actions.

When parents are seen as responding appropriately to

antisocial and prosocial behaviors, teens are more attentive

to parental prosocial value messages, and more open to

accepting such messages. Further, when parents respond

86 J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495

1 3

appropriately to their adolescents behaviors, it is more

reinforcing of positive behaviors, leading teens to place

greater value on such actions. As teens internalize prosocial

values, these serve to guide and motivate prosocial actions.

Therefore, we sought to test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 We hypothesized that adolescents who

perceived their parents responses to prosocial and antiso-

cial behaviors as more appropriate would place greater

importance on prosocial values. The social cognitive

framework allows for parental reactions in both prosocial

and antisocial contexts to affect adolescents motivation

toward positive behaviors. However, a prior study reported

that expected parental reactions to prosocial behaviors

were typically more strongly related to adolescents pro-

social behaviors than expected parental reactions to

antisocial behaviors (Wyatt and Carlo 2002).

Hypothesis 2 It was anticipated that adolescents who

more strongly endorsed prosocial values would also have

greater tendencies towards prosocial behaviors.

Hypothesis 3 We proposed that prosocial values would

mediate relations between expected parental reactions (to

prosocial and antisocial behaviors) and prosocial

behaviors.

Method

Participants

Participants were 140 adolescents (M age = 16.76 years,

SD = .80; 64% girls; 91% European American), their

parent, and their teachers from a public high school in a

mid-size city (approximate city population was 250,000) in

the Midwestern region of the United States. In terms of

mothers education, 71% of the mothers of the adolescents

in the present sample had at least a 4-year degree from

college or university (mothers education level is often

used as a proxy for socioeconomic status; Bornstein et al.

2003). Further, 82% of teens had parents who were married

and had never been divorced or separated.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through a local public high

school during spring semester. First, we identied a group

of four teachers willing to participate in the study; they

taught in psychology (male), family and consumer sci-

ences (female), computer technology (female), and

biology (female). Second, we went into the classrooms

and presented the study, and interested students took

home a packet that included a letter to their parents, the

parental consent form, and a parent-report measure of the

adolescents tendencies to engage in prosocial behaviors

across a range of contexts. Only the psychology courses

offered extra credit, and thus those courses had the

highest rates of participation (approximately 95%). Other

courses ranged from 25 to 75% participation. Third, stu-

dents who returned the parental consent form were asked

to sign the student assent form, and to complete the

adolescent questionnaires. Most students who took home

packets returned the consent form. Fourth, a teacher-

report measure of adolescents prosocial behavior was

obtained for each of the students who participated in the

study.

Measures

Expected Parental Reactions

Adolescents perceptions of the appropriateness with which

they expected their parents to react to their prosocial and

antisocial behaviors were assessed using the 16-item

expected parental reactions (EPR) questionnaire (Wyatt

and Carlo 2002). Adolescents were presented with 16

scenarios where they have hypothetically done something

antisocial or prosocial and asked to Please rate each of the

following statements on how appropriately your parent

might react to the situation on a ve-point scale (ranging

from 1 = not at all appropriately to 5 = very appropri-

ately). Adolescents with more than one parent were asked

to respond in terms of the parent they felt closest to. There

were 8 items for expected parental reactions to prosocial

behaviors (a = .78; sample item, If I were to lend

someone money for lunch, my parent would react), and

8 items for expected parental reactions to antisocial

behaviors (a = .90; sample item, If I had to stay after

school for starting a ght, my parent would react; for

additional information on measurement design, reliability,

and validity, see Wyatt and Carlo 2002).

Prosocial Values

We used three items from the Values-in-Action Inventory

of Strengths for youth (VIA-youth; Peterson and Seligman

2004) to assess the extent to which the adolescents valued

and enjoyed helping and being kind to others. The

VIA-youth assesses 24 different values (e.g., bravery,

creativity). For the present study, we used the three items

(a = .65) from the kindness subscale that seemed most in

lined with the denitions of values presented earlier (other

items seemed to be assessing behaviors more than values).

Adolescents rated statements, using a scale from 1

(very much unlike me) to 5 (very much like me), according

to how much the statements described them personally

J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495 87

1 3

(sample item: I enjoy being kind to others). The

VIA-youth has demonstrated adequate validity and reli-

ability across adolescent samples (e.g., Hardy and Carlo

2005; Peterson and Seligman 2004).

Prosocial Behavioral Tendencies

The prosocial tendencies measure (PTM-R; Carlo et al.

2003) was used to assess six different prosocial behavioral

tendencies that vary in terms of situations (e.g., emergency

situations) and motives (e.g., altruism). We modied this

original self-report measure for use as a parent- and tea-

cher-report measure by retaining the highest loading items

from each subscale (based on a prior dataset that used the

self-report version) and by modifying the stem of the

statements. We decided to use two independent reporters

for several reasons. First, using other-report measures such

as from teachers and parents helps reduce social desir-

ability and shared method biases (Nederhof 1985). Second,

getting varying perspectives on an individuals behavior

can be helpful, particularly when the different reporters

tend to observe the individuals in different contexts and

social roles (e.g., teachers versus parents; Noland and

McCallum 2000). Prior researchers have reported adequate

reliability and validity (including convergent validity) on

the PTM (e.g., Carlo et al. 2003; Carlo and Randall 2002;

Hardy and Carlo 2005).

For the 24-item parent-report version (PTM-P), parents

rated (using a scale from 1 = very unlikely to 5 = very

likely) their adolescents likelihood of exhibiting six types

of behaviors to someone else (6 items), to a teacher

(6 items) and to another student (6 items). The six

subscales were (with sample items): compliant (a = .65;

when they ask for help), anonymous (a = .77;

without people knowing he/she helped.), dire

(a = .82; when there is an emergency situation.),

emotional (a = .85; when the situation is emotionally

evocative.), altruism (a = .81; when there might be a

cost to him/herself.), and public (a = .77; when other

people are watching.).

For the 12-item teacher-report version (PTM-T), teach-

ers rated (using a scale from 1 = very unlikely to 5 = very

likely) their students likelihood of exhibiting six types of

behaviors to you (the teacher; 6 items) and to another

student (6 items). The six subscales were (with sample

items): compliant (a = .91; when they ask for help),

anonymous (a = .93; without people knowing he/she

helped.), dire (a = .86; when there is an emergency

situation.), emotional (a = .92; when the situation is

emotionally evocative.), altruism (a = .94; when

there might be a cost to him/herself.), and public

(a = .92; when other people are watching.).

Results

Descriptive Statistics, Gender Differences,

and Interrelations among Study Variables

Means and standard deviations for all the observed study

variables are presented in Table 1, and bivariate correla-

tions in Table 2. Expected parental reactions to prosocial

Table 1 Descriptive statistics

for all observed variables

included in SEM models

Sample sizes ranged from

n = 131 to 140

Variables Range M SD

Expected parental reactions to antisocial behavior 15 3.31 .83

Expected parental reactions to prosocial behavior 15 4.44 .49

Prosocial values item 1 (I really enjoy doing small favors for friends.) 15 4.22 .70

Prosocial values item 2 (I love to make other people happy.) 15 4.47 .66

Prosocial values item 3 (I enjoy being kind to others. 15 4.46 .64

Parent-report prosocial behavioral tendenciescompliant 15 4.50 .46

Parent-report prosocial behavioral tendenciespublic 15 4.36 .54

Parent-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesanonymous 15 4.37 .57

Parent-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesdire 15 4.75 .41

Parent-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesemotional 15 4.06 .67

Parent-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesaltruistic 15 3.85 .67

Teacher-report prosocial behavioral tendenciescompliant 15 4.15 .75

Teacher-report prosocial behavioral tendenciespublic 15 4.13 .74

Teacher-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesanonymous 15 4.10 .76

Teacher-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesdire 15 4.60 .60

Teacher-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesemotional 15 4.11 .76

Teacher-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesaltruistic 15 3.97 .92

88 J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495

1 3

behavior were positively correlated with one of the pro-

social values items (item 3). Further, at least one of the

prosocial values items was positively correlated with

parent-report compliant and altruistic prosocial behavioral

tendencies, and with all of the teacher-report prosocial

behavioral tendencies. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs)

by gender found girls to be signicantly higher on two of

the prosocial values items (item 2 and item 3) and ve of

the six forms of teacher-report prosocial behavioral ten-

dencies (compliant, public, anonymous, emotional, and

altruistic).

Structural Equation Modeling

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the

hypothesized mediation model whereby adolescents

expected parental reactions to prosocial and antisocial

behavior were proposed to predict adolescents prosocial

behavioral tendencies indirectly by way of adolescents

prosocial values. The model involves four variables:

adolescents expected parental reactions to prosocial

behavior, adolescents expected reactions to antisocial

behavior, prosocial values, parent-report adolescents

prosocial behavioral tendencies, and teacher-report ado-

lescents prosocial behavioral tendencies. However, given

the modest sample size, it was not feasible to create

latent variables in the SEM mediation model for all the

study variables. Rather, latent variables were only cre-

ated for the endogenous variables (the mediator and

outcomes). The two predictor variables (expected

parental reactions to prosocial and antisocial behaviors)

each involved eight items, and thus creating latent

variables would have required item parceling; therefore,

rather than creating latent variables, composite scores

were computed taking the mean of the eight items for

each variable.

One key benet of SEM is that it allows researchers to

simultaneously estimate all the model parameters for

complex models such as the mediation model hypothesized

in the present study. The structural portion of the mediation

model involved a number of paths between study variables.

First, there were paths from the predictors (expected

parental reactions to prosocial and antisocial behavior) to

Table 2 Bivariate correlations among all observed variables included in the SEM models

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

EPRAnti

EPRPro .38*

Pro values 1 .05 .11

Pro values 2 .08 .05 .35*

Pro values 3 .10 .21* .32* .49*

P-R compliant .09 .10 .15 .16 .19*

P-R public -.02 -.04 .09 .07 .05 .71*

P-R anon .10 .08 .01 .04 .16 .75* .72*

P-R dire -.06 .09 .08 .05 -.003 .36* .35* .33*

P-R emotional .06 .08 .06 .07 .15 .40* .47* .44* .38*

P-R altruistic .13 -.04 .10 .21* .13 .56* .57* .68* .27* .52*

T-R compliant .003 .09 .24* .18* .19* .13 .11 .07 .07 -.06 .004

T-R Public .02 .07 .26* .18* .19* .12 .10 .07 .07 -.06 .04 .97*

T-R Anon .02 .08 .27* .17 .19* .12 .09 .06 .10 -.05 .01 .96* .97*

T-R Dire -.04 .05 .16 .17* .23* .06 .10 .08 .10 .04 .05 .61* .61* .58*

T-R Emotional .03 .08 .26* .20* .20* .13 .10 .06 .10 -.05 .05 .96* .97* .97* .59*

T-R Altruistic .04 .05 .24* .21* .23* .11 .08 .07 .03 -.05 .02 .91* .91* .93* .52* .92*

Sample sizes ranged from n = 129 to 140; * p \.05

(EPRanti), expected parental reactions to antisocial behavior; (EPRpro), expected parental reactions to prosocial behavior; (pro values 1),

prosocial values item 1; (pro values 2), prosocial values item 2; (pro values 3), prosocial values item 3; (P-R compliant), parent-report prosocial

behavioral tendenciescompliant; (P-R public), parent-report prosocial behavioral tendenciespublic; (P-R anon), parent-report prosocial

behavioral tendenciesanonymous; (P-R dire), parent-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesdire; (P-R emotional), parent-report prosocial

behavioral tendenciesemotional; (P-R altruistic), parent-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesaltruistic; (T-R compliant), teacher-report

prosocial behavioral tendenciescompliant; (T-R public), teacher-report prosocial behavioral tendenciespublic; (T-R anon), teacher-report

prosocial behavioral tendenciesanonymous; (T-R dire), teacher-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesdire; (T-R emotional), teacher-report

prosocial behavioral tendenciesemotional; (T-R altruistic), teacher-report prosocial behavioral tendenciesaltruistic

J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495 89

1 3

the mediator (prosocial values).

1

Second, there were paths

from the mediator to the two outcomes (parent-reports and

teacher-reports of adolescents prosocial behavioral

tendencies).

Within SEM, models are evaluated at two levels: overall

model t and individual parameters subsumed within the

model. Because of the limitations of the v

2

-square likeli-

hood ratio test statistics, many researchers have suggested

using multiple measures of descriptive model t to deter-

mine overall model t (e.g., Hoyle 2000). In the current

study, the following indices were employed in addition to

the Yuan-Bentler Scale v

2

test: (a) the Comparative Fit

Index (CFI; Bentler 1990), with values greater than .93

indicating reasonable model t; and (b) the standardized

root mean residual (SRMR), with values less than .08

indicating reasonable model t (Hu and Bentler 1999). In

evaluating the statistical signicance of individual model

parameters [e.g., factor loadings, structural (path) coef-

cients], an alpha level of .05 was employed. For all models,

parameters were estimated using the full-information

maximum likelihood missing data estimation procedure

employed by EQS (Bentler 2008). In addition, the robust

procedure provided by EQS was used to correct for mul-

tivariate non-normality in the data.

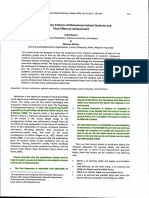

The estimated mediation model t well according to

descriptive t indices, Y-Bv

2

(N = 140, df = 116) =

136.88, p = .09, CFI = .99, SRMR = .04. All standard-

ized parameter values appear in Fig. 1. Moreover, all factor

loadings were large, positive, and statistically signicant;

suggesting viable latent prosocial values and prosocial

behavioral tendencies variables.

As hypothesized, perceptions of appropriateness of

expected parental reactions to prosocial behavior was sig-

nicantly related to prosocial values (R

2

= .04), which in

turn, was signicantly and positively related to both parent-

(R

2

= .04), and teacher-reports (R

2

= .08) of adolescents

prosocial behavioral tendencies (Fig. 1). MacKinnons

asymmetric condence interval was calculated to deter-

mine if this mediated effect was statistically signicant

(MacKinnon et al. 2002). The mediated effects for both

parent- and teacher-report of adolescents prosocial

behavioral tendencies were .01.08 and .02.11, respec-

tively. Because neither condence interval contained 0,

mediation is supported. However, the direct relation

between expected parental reactions to antisocial behaviors

and prosocial values was not signicant.

We ran a second model that included direct paths from

the expected parental reactions predictor variables to the

prosocial behavioral tendencies outcome variables. This

model t well according to the descriptive t indices,

Y-Bv

2

(N = 140, df = 112) = 134.23, p = .08, CFI =

.99, SRMR = .04. However, neither of the additional

direct effects from expected parental reactions to the pro-

social behavioral tendencies outcome variables was

statistically signicant (bs ranged from -.03 to .05, all

ps [.05). This reinforces the hypothesized mediated effect

between expected parental reactions and prosocial behav-

iors through kindness.

Prosocial

Values

Item 1 Item 2 Item 3 compliant

emotional anonymous

public dire

altruism

.18*

.50*

.67*

.71*

.73*/

.93*

.83*/

.98*

.41*/

.60*

.82*/

.98*

.55*/

.98*

.89*/

.98*

.21*/.31*

.06

Expected

Parental

Reactions to

Prosocial

Behavior

Expected

Parental

Reactions to

Antisocial

Behavior

Prosocial

Behavioral

Tendencies

.38*

Fig. 1 Factor loadings and structural path coefcients for the

mediating role of prosocial values on the relations between expected

parental reactions to prosocial and antisocial behaviors and parent-

reported and teacher-reported prosocial behavioral tendencies. For all

model parameters involving the prosocial behavioral tendencies latent

variable, the rst number represents the parent-reported prosocial

behavioral tendencies latent variable and the second number repre-

sents the teacher-reported prosocial behavioral tendencies latent

variable. All reported model parameters are standardized values

(*p \.05)

1

A direct link from the predictor to outcome was necessary for

earlier conceptions of mediation (Baron and Kenny 1986). However,

more recently MacKinnon et al. (MacKinnon et al. 2002, 2007) have

argued that a signicant direct link be should not be a necessary

criteria for mediation, as long as the indirect path is signicant. In

fact, they state that such cases of signicant indirect but not direct

relations between predictors and outcomes are quite common, and

demonstrate that most of the links between the predictors and

outcomes are mediational. Moreover, requiring a signicant direct

effect reduces the power to detect true mediation effects.

90 J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495

1 3

Finally, the invariance of both the measurement and

structural parameters of the model was tested across gender

using the LaGrange multiplier of constraints. The LaGrange

multiplier is a multivariate test that tests for the statistical

signicance of each constraint, controlling for the other

constraints. This model t well according to descriptive t

indices, Y-Bv

2

(N = 140, df = 468) = 697.12, p \.05,

CFI = .92, SRMR = .07. Moreover, all model parameters

were invariant across gender (all ps [.05). Thus, there

were no differences in the relations between variables

across boys and girls.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to test a mediation

model whereby adolescents perceptions of the appropri-

ateness with which they expected their parents to respond

to their prosocial and antisocial behaviors was posited to

relate to the adolescents tendencies to engage in prosocial

behaviorsbut indirectly by way of adolescents prosocial

values. In general the results supported the hypothesized

mediation model. Adolescents who perceived their parents

as responding appropriately to their prosocial behaviors

placed greater value on such behaviors, and in turn ado-

lescents who valued prosocial behaviors more were

perceived by parents and teachers as more likely to engage

in prosocial behaviors. However, adolescents perceptions

of the appropriateness of parental responses to antisocial

behaviors were not predictive of their prosocial values.

These ndings provide support for the social cognitive

framework suggesting importance of adolescents social

cognitions such as expectancies and values in understand-

ing adolescents prosocial responding (Bandura 1986;

Eccles and Wigeld 2002; Nelson and Crick 1999).

In partial support of Hypothesis 1, adolescents who

perceived more appropriate parental reactions to prosocial

behaviors (but not reactions to antisocial behaviors) more

strongly valued and enjoyed prosocial behaviors. This

pattern of ndings is similar to prior work on expected

parental reactions (e.g., Wyatt and Carlo 2002). These

results suggest that parental reactions in prosocial behav-

ioral contexts, and perhaps more importantly adolescents

perceptions and evaluations of these parental reactions,

might play a role in the process by which values are

internalized in adolescence (Grusec and Goodnow 1994). It

seems that when adolescents see their parents as respond-

ing fairly and conveying reasonable values messages they

are more open to listening to and accepting such messages.

Consistent with this notion, a prior study revealed that

adolescents who expected their parents to react appropri-

ately to their prosocial and antisocial behaviors were more

likely to view their parents intentions as caring and

helpful, and to report that their parents tended to express

more positive affect, and use less yelling and more talking

(Padilla-Walker and Carlo 2004).

It is unclear why adolescents perceptions of the

appropriateness of their parents reactions to their antiso-

cial behaviors did not signicantly predict their prosocial

values. A prior study looking at expected parental reactions

and youth outcomes similarly found expected parental

reactions to prosocial situations, but not expected parental

reactions to antisocial situations, to be predictive of teens

prosocial behavioral tendencies, while both were nega-

tively associated with teens aggression. It seems possible

that the reinforcement of prosocial behaviors that comes

when parents appropriately respond to such behaviors is a

more salient inuence on teens values and motivations

than punishment for negative behaviors. In a sense, these

differential ndings for parenting in prosocial and antiso-

cial contexts are interesting because while most prior

theory and empirical work on the internalization of values

and the socialization of moral behaviors has emphasized

discipline situations (e.g., Grusec 2006; Hoffman 2000),

the present ndings support arguments for considering

parenting in prosocial contexts (e.g., where teens have done

something positive; Eisenberg et al. 2006; Staub 1979;

Wyatt and Carlo 2002). Taken together with other recent

ndings (Padilla-Walker and Carlo 2004, 2006, 2007;

Wyatt and Carlo 2002), the present results add to the

growing evidence that contrasts with psychoanalytic and

conscience internalization theorists who emphasize trans-

gressive, discipline contexts as the primary socialization

contexts for facilitating moral development (e.g., Grusec

2006; Hoffman 2000; Kochanska 1993). These traditional

approaches suggest that discipline contexts are most sig-

nicant for inculcating moral values because of the often

intense emotional climate that makes those encounters

salient and memorable to the child. However, more

recently, scholars have noted the need for greater attention

to the effects of parenting in prosocial behavior contexts on

moral development (Eisenberg et al. 2006; Grusec 2006).

One might argue that parental reactions to adolescents

prosocial behaviors are also emotionally salient and thus

equally important moral socialization contexts. For

instance, an adolescent may feel joy and pride at being

praised for a prosocial act, or feel embarrassment or dis-

appointment if the prosocial act is not acknowledged and

positively reinforced. Although transgressive contexts

present opportunities to emphasize what parents prohibit

and consider morally wrong, prosocial behavior contexts

present opportunities for parents to emphasize what is

condoned and considered morally correct.

In support of Hypothesis 2, prosocial values signicantly

predicted parents and teachers reports of adolescents

prosocial behavioral tendencies. In other words, adolescents

J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495 91

1 3

who placed more value on prosocial behaviors also were

perceived by their parents and teachers as more likely to

engage in prosocial behaviors across a variety of contexts.

This is in line with prior work showing links between values

and behaviors (for reviews, Bardi and Schwartz 2003; Hitlin

and Piliavin 2004; Rohan 2000), including several studies

focused on prosocial functioning during adolescence

(Padilla-Walker 2007; Padilla-Walker and Carlo 2007; Pratt

et al. 2003), and provides additional support for the notion

that valuing a given course of action can provide personal

motivation to pursue that course of action (Bardi and Sch-

wartz 2003; Manstead 1996; Ryan and Connell 1989;

Verplanken and Holland 2002). In contrast to prior studies

examining the relations among parental expectancies, val-

ues, and prosocial behaviors, the present ndings were

based on multiple reports of adolescents prosocial behav-

ioral tendencies, which reduces problems with social

desirability and shared method variance biases.

In line with Hypothesis 3, expected parental reactions

to prosocial behavior was indirectly related to prosocial

behavioral tendencies via adolescents prosocial values

but was not directly related to prosocial behavioral ten-

dencies. These ndings are consistent with work on the

internalization of values which suggests that parental

socialization processes work to inuence teen behaviors

via the transmission of moral values and traits (Eisenberg

et al. 2006; Grusec and Goodnow 1994; Padilla-Walker

and Carlo 2007). The fact that parental socialization

practices did not directly predict teens prosocial behav-

ioral tendencies might help explain individual differences

in prosocial behaviors. That is, as Grusec and Goodnow

(1994) noted, there are individual differences in childrens

openness and acceptance of parental moral messages and

these translate into individual differences in the extent to

which children internalize moral values. In a recent study,

investigators found support for this notion such that

accurate perception and acceptance predicted internaliza-

tion of values, which in turn, predicted prosocial

behaviorsmore importantly perhaps was that there were

no direct paths between acceptance and accurate percep-

tion and prosocial behaviors (Padilla-Walker 2007; see

also Carlo et al. 2007). Thus, the meditational effect of

values on the relations between expected parental reac-

tions and prosocial behavioral tendencies in the present

study was consistent with other reported meditational

effects in recent studies on the socialization of prosocial

behaviors and suggest that there are differences in the

extent to which children internalize moral values even

when parents might use similar parenting practices. Fur-

ther research should examine the possible mediating

effects of other social cognitions (e.g., moral reasoning)

and moral emotions (e.g., sympathy) on the relations

between parenting and prosocial behaviors.

In summary, the results suggest that adolescents who

perceive their parents as responding appropriately to their

prosocial behaviors might place more value on prosocial

behaviors, and adolescents with more internalized proso-

cial values might engage in prosocial behaviors more

frequently. In other words, one route by which parenting

practices may inuence adolescents prosocial behaviors is

by way of two facets of their social cognition: the way they

perceive of and evaluate their parents behaviors, and the

value they place on prosocial behaviors. Thus, researchers

and parents should not only attend to what parents do, but

to how adolescents perceive of and respond to such par-

enting behaviors, and the impact of these social cognitions

on adolescents motivations and behaviors. In other words,

in some cases it may not be what the parent actually does

that is at issue, but the adolescents interpretations.

One additional interesting pattern of results worth

mentioning was the lack of correlation between parents

and teachers reports of adolescents prosocial behavioral

tendencies. Recent evidence supports the value and validity

of using multiple informant reports in addition to or in

place of self-reports (Vazire 2006). However, it should not

be assumed that informant reports will always agree. Par-

ents and teachers observe adolescents in different social

contexts, and play different roles in their lives. Thus, it is

not surprising that they have different perceptions of the

youth. Further, some argue that personality does not nec-

essarily entail consistent responding across contexts

(Cervone 2005). However, the fact that the valuing of

prosocial behavior was positively related to both reports of

adolescents prosocial behavioral tendencies suggests that

these disparate reports may both be tapping a similar

construct.

Although we found support for the proposed mediation

model, there are several important limitations to the

present study. First, a rigorous examination of the role of

values will require the need to more condently establish

direction of causality through more sophisticated study

designs (e.g., longitudinal design, experimental manipula-

tion). There is growing recognition that there are reciprocal

inuence paths such that children also impact parenting

practices (Kuczynski et al. 1997). Furthermore, there is

evidence that parents also have expectancies about their

childrens moral actions, and that those expectancies are

likely to inuence their actions and reactions (Sigel and

McGillicuddy-De Lisi 2002; Smetana 1997). Second, the

present sample was largely white, middle-class families,

and thus, the study ndings might be specic to that

demographic. Prior research has found that parenting styles

and practices and their relation to adolescent outcomes

often differ across cultures and even across ethnic groups

in the US (for a review, see Arnett 2007). It is possible that

the mechanisms in our model function similarly across

92 J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495

1 3

various demographic groups, but, what is seen as appro-

priate might differ. However, future research needs to

explore these mechanisms across different cultures and

ethnicities. Third, the path coefcient effect sizes ranged

from small to medium (using Cohens classication

scheme; Cohen and Cohen 1983); thus, necessitating future

research on other potential important predictors. Speci-

cally, more needs to be done to elucidate other mediators

(e.g., attachment style) and moderators (e.g., parentado-

lescent relationship quality) involved in the socialization of

prosocial values and behaviors. Additionally, obviously

parents are not the only inuence on prosocial development;

thus, research is needed comparing and contrasting parental

inuence to that of other socialization agents such as peers,

religion, and schools. Fourth, when adolescents were asked

to report on their perceptions of the appropriateness of their

parents reactions to their prosocial and antisocial behav-

iors, they were only required to respond regarding the

parent to whom they felt closest. While this could poten-

tially be problematic (e.g., the parent they feel closest to

might not be the parent who is most inuential in terms of

their values and behaviors), in most cases we think it was

the same parent who also completed the measure of their

adolescents prosocial behavioral tendencies. Thus, there

was likely some consistency across the measures.

Conclusions

There are several important implications of the present

study. First, this research further demonstrates the central

role of adolescents social cognitions in understanding the

links between parenting and prosocial behaviors. Work on

adolescents expectancies (such as expected parental reac-

tions) is surprisingly sparse, even though the notion is well-

grounded in social cognitive theory (e.g., Bandura 1986;

Grusec and Goodnow 1994). Additionally, in the moral

development literature, moral values tend to be overshad-

owed by an emphasis on moral reasoning and moral

emotions (Lapsley 1996). But, more research on the social-

ization of values is warranted given increased scholarly

interest in examining moral development constructs other

than moral reasoning and moral emotions (Hart 2005;

Lapsley and Narvaez 2004), and given the increasing focus

of values and virtues in many moral and character education

programs (Lapsley and Narvaez 2006). Second, while most

prior work on parenting behaviors has emphasized how

parents respond to negative behaviors (e.g., discipline;

Grusec 2006; Hoffman 2000), the present ndings uphold

arguments for also considering how parents respond to

positive behaviors (Eisenberg et al. 2006; Staub 1979; Wyatt

and Carlo 2002). These prosocial situations may be just as

salient as discipline situations in providing opportunities to

guide youth in the right direction. Third, research on ado-

lescents perceptions of appropriateness of parental

reactions emphasizes the active, interpretive role of children

in their development (Smetana 1997) and suggests an alter-

native research venue (to the traditional research on

parenting styles and practices) for studying the impact of

parental socialization. In other words, rather than focus

simply on what the parents do, researchers should further

example adolescents social cognitions relevant to parental

behaviors. Finally, although much of the prior work on moral

socialization has indeed focused on childhood (for reviews,

see Eisenberg et al. 2006; Eisenberg and Valiente 2002), the

evidence points towards continued prosocial development

(Colby and Damon 1992; Eisenberg and Valiente 2002) and

parental inuence (Padilla-Walker et al. 2008) into adult-

hood. There is a clear need for more theoretical and empirical

work targeted at understanding the processes of moral

socialization and prosocial development across adolescence.

Acknowledgments Funding support was provided by a grant from

the Values-In-Action Institute to Gustavo Carlo. The authors would

like to thank the teachers, staff, parents, and students at Lincoln

Southeast High School for their generous cooperation and assistance.

Data for this project was collected while Sam Hardy was at the

University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Correspondence may be addressed to

Sam Hardy, Department of Psychology, Brigham Young University,

Provo, UT 84602, sam_hardy@byu.edu.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005). The inuence of attitudes on

behavior. In D. Albarrac , B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.),

The handbook of attitudes (pp. 173221). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Adolescence and emerging adulthood: A cultural

approach (3rd ed.). Upper Sadle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A

social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bardi, A., & Schwartz, S. H. (2003). Values and behavior: Strength

and structure of relations. Personality and Social Psychology

Bulletin, 29, 12071220. doi:10.1177/0146167203254602.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderatormediator

variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual,

strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 51, 11731182. doi:10.1037/0022-

3514.51.6.1173.

Baumrind, D. (1991). The inuence of parenting style on adolescent

competence and substance abuse. The Journal of Early Adoles-

cence, 11, 5695. doi:10.1177/0272431691111004.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative t indexes in structural models.

Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238246. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.

107.2.238.

Bentler, P. M. (2008). EQS 6 structural equations program manual.

Encino, CA: Multivariate Software, Inc. (www.mvsoft.com) (in

press).

Bornstein, M. H. (Ed.). (2002). Handbook of parenting. Vol 1:

Children and parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Bornstein, M. H., Hahn, C., Suwalksy, J. T. D., & Haynes, O. M.

(2003). Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development:

J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495 93

1 3

The Hollingshead four-factor index of social status and the

socioeconomic index of occupations. In M. H. Bornstein & R. H.

Bradley (Eds.), Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child

development (pp. 2982). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Carlo, G., Fabes, R. A., Laible, D., & Kupanoff, K. (1999). Early

adolescence and prosocial/moral behavior II: The role of social

and contextual inuences. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 19,

133147. doi:10.1177/0272431699019002001.

Carlo, G., Hausmann, A., Christiansen, S., & Randall, B. A. (2003).

Sociocognitive and behavioral correlates of a measure of

prosocial tendencies for adolescents. The Journal of Early

Adolescence, 23, 107134. doi:10.1177/0272431602239132.

Carlo, G., McGinley, M., Hayes, R., Batenhorst, C., & Wilkinson, J.

(2007). Parenting styles or practices? parenting, sympathy, and

prosocial behaviors among adolescents. The Journal of Genetic

Psychology, 168, 147176. doi:10.3200/GNTP.168.2.147-176.

Carlo, G., & Randall, B. A. (2002). The development of a measure of

prosocial behaviors for late adolescence. Journal of Youth and

Adolescence, 31, 3144. doi:10.1023/A:1014033032440.

Cervone, D. (2005). Personality architecture: Within-person struc-

tures and processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 423452.

doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070133.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correla-

tion analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Colby, A., & Damon, W. (1992). Some do care: Contemporary lives

of moral commitment. New York: The Free Press.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of

social information-processing mechanisms in childrens social

adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74101. doi:10.1037/

0033-2909.115.1.74.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigeld, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and

goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109132. doi:10.1146/

annurev.psych.53.100901.135153.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial

development. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Series Eds.), N.

Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3.

Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp.

646718). New York: Wiley.

Eisenberg, N., & Valiente, C. (2002). Parenting and childrens

prosocial and moral development. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.),

Handbook of parenting: Vol. 5. Practical issues in parenting (2nd

ed., pp. 111142). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Grusec, J. E. (2006). The development of moral behavior and

conscience from a socialization perspective. In M. Killen & J.

Smetana (Eds.), Handbook of moral development (pp. 243265).

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Grusec, J. E., & Goodnow, J. J. (1994). The impact of parental

discipline methods on childs internalization of values: A

reconceptualization of current points of view. Developmental

Psychology, 30, 419. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.4.

Hardy, S. A., &Carlo, G. (2005). Adolescent religiosity, prosocial values,

and prosocial behaviors: A mediational analysis. Journal of Moral

Education, 34, 231249. doi:10.1080/03057240500127210.

Hart, D. (2005). The development of moral identity. In G. Carlo & C.

P. Edwards (Eds.), Moral motivation through the lifespan Vol.

51. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (pp. 165196). Lincoln:

University of Nebraska Press.

Hitlin, S., & Piliavin, J. A. (2004). Values: Reviving a dormant

concept. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 359393. doi:10.1146/

annurev.soc.30.012703.110640.

Hoffman, M. L. (2000). Empathy and moral development: Implica-

tions for caring and justice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Hoyle, R. H. (2000). Conrmatory factor analysis. In H. E. A. Tinsley

& S. D. Brown (Eds.), Handbook of applied multivariate

statistics and mathematical modeling (pp. 465497). San Diego,

CA: Academic Press.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for t indexes in

covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new

alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 155.

Kochanska, G. (1993). Toward a synthesis of parental socialization

and child temperament in early development. Child Develop-

ment, 64, 325347. doi:10.2307/1131254.

Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive develop-

mental approach to socialization. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.),

Handbook of socialization theory and research (pp. 347480).

Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Kuczynski, L., Marshall, S., & Schell, K. (1997). Value socialization

in a bidirectional context. In J. E. Grusec & L. Kuczynski (Eds.),

Parenting and childrens internalization of values: A handbook

of contemporary theory (pp. 2350). New York: Wiley.

Lapsley, D. (1996). Moral psychology. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Lapsley, D. K., & Narvaez, D. (2004). A social-cognitive approach to

the moral personality. In D. K. Lapsley & D. Narvaez (Eds.),

Moral development, self and identity (pp. 189212). Mahwah,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Lapsley, D. K., & Narvaez, D. (2006). Character education. In W.

Damon & R. Lerner (Series Eds.), K. A. Renninger & I. E. Sigel

(Vol. Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Child

psychology in practice (6th ed.; pp. 248296). New York: Wiley.

Maccoby, E., & Martin, J. (1983). Socialization in the context of the

family: Parentchild interactions. In P. H. Mussen (Series Ed.),

E. M. Hetherington (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology:

Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (pp. 1

101). New York: Wiley.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation

analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593614.

doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., &

Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation

and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7,

83104. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83.

Manstead, A. S. R. (1996). Attitudes and behaviour. In G. R. Semin &

K. Fiedler (Eds.), Applied social psychology (pp. 329).

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nederhof, A. J. (1985). Methods of coping with social desirability

bias: A review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 15,

263280. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420150303.

Nelson, D. A., & Crick, N. R. (1999). Rose-colored glasses:

Examining the social information-processing of prosocial young

adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 19, 1738.

doi:10.1177/0272431699019001002.

Noland, R. M., & McCallum, R. S. (2000). A comparison of parent

and teacher ratings of adaptive behavior using a universal

measure. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 18, 3948.

doi:10.1177/073428290001800104.

Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2007). Characteristics of motherchild interac-

tions related to adolescents positive values and behaviors. Journal

of Marriage and the Family, 69, 675686. doi:10.1111/j.1741-

3737.2007.00399.x.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Carlo, G. (2004). Its not fair! Adolescents

constructions of appropriateness of parental reactions to antisocial

and prosocial situations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33,

389401. doi:10.1023/B:JOYO.0000037632.46633.bd.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Carlo, G. (2006). Adolescent perceptions of

appropriate parental reactions in moral and conventional social

domains. Social Development, 15, 480500. doi:10.1111/j.1467-

9507.2006.00352.x.

94 J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495

1 3

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Carlo, G. (2007). Personal values as a

mediator between parent and peer expectations and adolescent

behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 538541. doi:

10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.538.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Nelson, L. J., Madsen, S., & Barry, C. M.

(2008) The role of perceived parental knowledge on emerging

adults risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37,

847859.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and

virtues: A handbook and classication. Washington, D.C:

American Psychological Association.

Pratt, M. W., Hunsberger, B., Pancer, S. M., & Alisat, S. (2003). A

longitudinal analysis of personal value socialization: Correlates

of moral self-ideal in adolescence. Social Development, 12, 563

585. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00249.

Rohan, M. J. (2000). A rose by any name? the values construct.

Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4, 255277. doi:

10.1207/S15327957PSPR0403_4.

Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and

internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 749761.

doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.749.

Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1987). Toward a universal psycholog-

ical structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 53, 550562. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.550.

Sigel, I. E., & McGillicuddy-De Lisi, A. V. (2002). Parental beliefs

are cognitions: The dynamic belief systems model. In M. H.

Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting Vol. 3: Status and social

conditions of parenting (pp. 485508). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.

Smetana, J. G. (1997). Parenting and the development of social

knowledge reconceptualized: A social domain analysis. In J. E.

Grusec & L. Kuczynski (Eds.), Parenting and childrens

internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory

(pp. 162192). New York: Wiley.

Staub, E. (1979). Positive social behavior and morality: Socialization

and development. New York: Academic Press.

Vazire, S. (2006). Informant reports: A cheap, fast, and easy method

for personality assessment. Journal of Research in Personality,

40, 472481. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2005.03.003.

Verplanken, B., & Holland, R. W. (2002). Motivated decision

making: Effects of activation and self-centrality of values on

choices and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 82, 434447. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.434.

Wyatt, J. M., & Carlo, G. (2002). What will my parents think?

relations among adolescents expected parental reactions, pro-

social moral reasoning and prosocial and antisocial behaviors.

Journal of Adolescent Research, 17, 646666. doi:10.1177/

074355802237468.

Author Biographies

Sam Hardy is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psy-

chology at Brigham Young University. He received his Ph.D. in

Developmental Psychology from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

His major research interests include moral development, identity,

religion and spirituality, and internalization of values in adolescence.

Gustavo Carlo is the Carl A. Happold Professor of Psychology in

the Department of Psychology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

He received his Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology from Arizona

State University. His research interests focus on individual, parenting,

and cultural correlates of positive social and moral behaviors in

children and adolescents.

Scott Roesch is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psy-

chology at San Diego State University. He received his Ph.D. in

Social Psychology from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. His

major research interests include trait-state models of stress and cop-

ing; coping with physical illness, and particularly cancer; cultural,

ethnic, and acculturation differences in stress and coping; cross-ethnic

measurement equivalence; structural equation modeling; and meta-

analysis.

J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39:8495 95

1 3

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

TITLE: Links Between Adolescents Expected Parental Reactions

and Prosocial Behavioral Tendencies: The Mediating Role

of Prosocial Values

SOURCE: J Youth Adolesc 39 no1 Ja 2010

The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it

is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in

violation of the copyright is prohibited. To contact the publisher:

http://www.springerlink.com/content/1573-6601/

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Three Approaches To Case Study Methods in Education - Yin Merriam PDFDocumento21 pagineThree Approaches To Case Study Methods in Education - Yin Merriam PDFIrene Torres100% (1)

- Assessing Parental Beliefs in Early Childhood - CrosbyDocumento9 pagineAssessing Parental Beliefs in Early Childhood - CrosbyEduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Parental and Child Cognitions in The Context of The FamilyDocumento31 pagineParental and Child Cognitions in The Context of The FamilyEduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Validating An Instrument For Clinical Supervision Using An Expert Panel - Hyrkäs, Appelqvist-Schmidlechner & Oksa (2003)Documento7 pagineValidating An Instrument For Clinical Supervision Using An Expert Panel - Hyrkäs, Appelqvist-Schmidlechner & Oksa (2003)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Modeling Answer Changes On Test Items - Van Der Linden & Jeon (2012)Documento21 pagineModeling Answer Changes On Test Items - Van Der Linden & Jeon (2012)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Elucidating The Etiology and Nature of Beliefs About Parenting StylesDocumento20 pagineElucidating The Etiology and Nature of Beliefs About Parenting StylesEduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Early History of The Kappa Statistic - Smeeton (1985)Documento2 pagineEarly History of The Kappa Statistic - Smeeton (1985)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Causal Attribution Patterns of Mainstream School Students and Their Effect On Achievement - Batool & Akhter (2012)Documento5 pagineCausal Attribution Patterns of Mainstream School Students and Their Effect On Achievement - Batool & Akhter (2012)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Findings Give Some Support To Advocates of Spanking - Goode NYT (2001)Documento4 pagineFindings Give Some Support To Advocates of Spanking - Goode NYT (2001)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Socialinnovation LabguideDocumento110 pagineSocialinnovation LabguideholeaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Kappa Statistic in Reliability Studies - Use, Interpretation, and Sample Size Requirements - Sim & Wright (2005) PDFDocumento13 pagineThe Kappa Statistic in Reliability Studies - Use, Interpretation, and Sample Size Requirements - Sim & Wright (2005) PDFEduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Child Outcomes of Nonabusive and Customary Physical Punishment by Parents - Larzelere (2000)Documento24 pagineChild Outcomes of Nonabusive and Customary Physical Punishment by Parents - Larzelere (2000)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Differences in Parent Behavior Toward Three and Nine Year Old Children - Baldwin (1946)Documento24 pagineDifferences in Parent Behavior Toward Three and Nine Year Old Children - Baldwin (1946)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Obstetric Complications and Aggression - IshikawaRaine (2003)Documento6 pagineObstetric Complications and Aggression - IshikawaRaine (2003)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bully-Victim Problems and Coping With Stress in School Among 10 - To 12-Year-Old Pupils in Åland, Finland - Olafsen & Viemerö (2000)Documento10 pagineBully-Victim Problems and Coping With Stress in School Among 10 - To 12-Year-Old Pupils in Åland, Finland - Olafsen & Viemerö (2000)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dynamic Structural Equation Models - Asparouhov Et Al (2018)Documento31 pagineDynamic Structural Equation Models - Asparouhov Et Al (2018)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Punishment, Nail-Biting, and Nightmares. A Cross-Cultural Study - Englehart & Hale (1990)Documento5 paginePunishment, Nail-Biting, and Nightmares. A Cross-Cultural Study - Englehart & Hale (1990)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Meta-Analysis of The Published Research On The Affective, Cognitive and ... of Corporal Punishment - Paolucci Violato (2004)Documento25 pagineA Meta-Analysis of The Published Research On The Affective, Cognitive and ... of Corporal Punishment - Paolucci Violato (2004)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Effectiveness of Psychoeducation and Systematic Desensitization To Reduce Test Anxiety Among First-Year Pharmacy Students - Rajiah & Saravanan (2014)Documento8 pagineThe Effectiveness of Psychoeducation and Systematic Desensitization To Reduce Test Anxiety Among First-Year Pharmacy Students - Rajiah & Saravanan (2014)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dynamic Structural Equation Models - Asparouhov Et Al (2018)Documento31 pagineDynamic Structural Equation Models - Asparouhov Et Al (2018)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Structured Equation ModellingDocumento17 pagineStructured Equation ModellingAbhishek MukherjeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Family-Based Psychoeducation For Children and Adolescents With Mood Disorders - Ong & Caron (2008)Documento15 pagineFamily-Based Psychoeducation For Children and Adolescents With Mood Disorders - Ong & Caron (2008)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Effectiveness of Psychoeducation and Systematic Desensitization To Reduce Test Anxiety Among First-Year Pharmacy Students - Rajiah & Saravanan (2014)Documento9 pagineThe Effectiveness of Psychoeducation and Systematic Desensitization To Reduce Test Anxiety Among First-Year Pharmacy Students - Rajiah & Saravanan (2014)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Child Rearing, Prosocial Moral Reasoning, and Prosocial Behaviour - Janssens & Dekovic (1997)Documento19 pagineChild Rearing, Prosocial Moral Reasoning, and Prosocial Behaviour - Janssens & Dekovic (1997)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- D 4165 1 PDFDocumento16 pagineD 4165 1 PDFalvimar_lucenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoeducation as Evidence-Based Practice: A Review of its Applications Across SettingsDocumento21 paginePsychoeducation as Evidence-Based Practice: A Review of its Applications Across SettingsEduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Recent Developments in Family Psychoeducation As An Evidence Based Practice - Lucksted Et Al (2012) PDFDocumento21 pagineRecent Developments in Family Psychoeducation As An Evidence Based Practice - Lucksted Et Al (2012) PDFEduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Early Outcomes of A Pilot Psychoeducation Group Intervention For Children of A Parent With A Psychiatric Illness - Riebsschleger Et Al (2009)Documento9 pagineEarly Outcomes of A Pilot Psychoeducation Group Intervention For Children of A Parent With A Psychiatric Illness - Riebsschleger Et Al (2009)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Early Outcomes of A Pilot Psychoeducation Group Intervention For Children of A Parent With A Psychiatric Illness - Riebsschleger Et Al (2009)Documento7 pagineEarly Outcomes of A Pilot Psychoeducation Group Intervention For Children of A Parent With A Psychiatric Illness - Riebsschleger Et Al (2009)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Brief Group Psychoeducation For Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures: A Neurologist-Initiated Program in An Epilepsy CenterDocumento12 pagineBrief Group Psychoeducation For Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures: A Neurologist-Initiated Program in An Epilepsy CenterEduardo Aguirre DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)