Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Research Essay

Caricato da

theonlytycraneCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Research Essay

Caricato da

theonlytycraneCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Thomas Bixby Dr.

E Multimedia Writing and Rhetoric 7 April 2014 Title The conceptual fabrication of gender identity within a young mind draws heavily from social influence to dictate the proper manner of masculine or feminine conduct. While in eons past gender identities were shaped by necessity, in the modern age survival does not hinge on adherence appropriate gender identity which leaves room for other forces to shape male and female minds. Without the physically dictated tasks of foraging, hunting, and protecting there is a lack of mediums with which to properly convey the essence of masculinity. Popular media has stepped into fill the void. Television and video games craft personas derived from the culturally established ideas of gender creating representations of the ideal concept of masculinity. This essay will focus on this masculinity and how it is marketed to young boys. This media glamorizes violence, sexuality, and material acquisition playing to the most fundamental nature of man. The primal nature of man has been tamed by logic and reason so out of fear to change the content of these forms of media has become bloodier and more sexual in order to maintain the norms of masculinity. All that this increase in violent portrayals has done, however, is increase aggression in young viewers and poison them with a perception of violence as an acceptable means of conflict resolution.

An act of aggression must meet certain stipulations. It must be directed at an individual with the intent to cause harm. The perpetrator of the aggressive act must expect said act to have a chance of harming the other individual who is motivated to avoid harm (Gentile 14). An act meeting the aforementioned standards then falls into separate subsets for more clarity of study. Physical aggression and violence which involves harm caused by direct physical means is the most commonly pictured form of aggression. Causing harm by verbal means or through print is labeled verbal aggression. The third type is called relational aggression which brings harm through the damage or of or threat towards relationships or feeling of acceptance. Rumor spreading, exclusion, and other forms of relational aggression have psychological impacts just as serious as the physical hurts brought on my violence (Gentile 15). Increased aggression reduces civility in conflict situations and can result in hot-blooded blunders which one may later look upon with regret or shame. Contemporary forms of media have been shown to have a relationship with increased aggression; mainly in young receptive minds. In her book Television and Child Development, Judith Van Evra discusses the relationship between television content and child behavior. One important relationship she notes is a causal one between viewing violence on TV or playing with violent video games and real-life aggression (83). The correlation or causality debate in regards to media exposure and behavior has gone on for some time. Originally the majority of researches agreed that there was some association between viewing violent media and violent behavior. Evidence, however,

remained inconclusive for some time due to a lack of sound studies and a firm belief by some that this association could be disproven if certain variables were controlled (83). Numerous researches for the last three decades set out to lay the debate to rest. One such pair, Comstock and Scharrer, conducted numerous studies in the late nineties to measure exposure to TV violence, aggressive or antisocial behavior, and other variables (82). What they found was incontestable empirical documentation of a positive relation between exposure to violence and aggressive and antisocial behavior which was consistent in surveys, laboratory experiments, field studies, and simulated aggression models (82). The clear causal relationship between exposures to violent media and aggressive behavior is troubling. To make matters worse, media glamorizes the violence in these fictional depictions and rarely do those enacting the violence get taken to justice. Even media crafted for children is not free from violent depictions. The issue arises in the young minds struggle to distinguish fantasy from reality. This well documented difficulty makes the risk of effect higher for children (Van Evra 79). For the most part boys show more interest in video games so most of the characters in them are boys, with whom young boys would be more likely to identify, (79). Cartoons are less skewed towards a single sex but featuring characters of similar age to the child increased the characters likeability, and creates a greater likelihood of the child thinking of the character as a role model and channel the aggression displayed by the character. Allowing for differences in patterns of exposure, the average American household has their television set on for 7 and a half hours each day (Ravitch, Viteritti 66). This offers ample time for a young mind to become exposed to a world of personality shaping influences which can have a lasting impact on the personal growth

of the individual. The feeling of content safety offered by E rated labels or childrens programming is a false. Even the most innocent portrayals of violent or aggressive interactions can have a grave impact on the mind of a young viewer. In 2002 it was learned that programming targeted at viewers who were younger than 12 had the most prevalent and concentrated violence than any other television genres (Van Evra 78). This violence is likely to be glamorized while also being censored of non-age appropriate images. Instead of reducing the impact of the violent programming, however, the sanitized depictions trivialize violence which makes it more likely for viewers to learn aggressive tendencies and become desensitized from viewing violent portrayals (79). Although cartoons and childrens video games do not show blood and gore, this does little to minimize their impact; it may in fact make it more potent. Because this media does not show lethal violence the acts depicted in them tend to be ones which use natural means and are less lethal, making them easier for children to duplicate or emulate, (79). Video games add an entirely new element with which to influence young minds. By allowing one to be involved in events rather than merely viewing them creates a level of connection that is lacking in television. Psychology expert Valerie Walkerdine discusses how video games allow the embodiment of fantasies of omnipotent masculinity (Walkerdine 46). She goes on to discuss how the effects of this simulated omnipotence even in non-violent games creates a desire within young boys for independence. This gives these children the sense that to be a man they must handle things on their own without the aid or counsel of others. If the game

is violent then the effects are more pronounced. Not only does the boy wish to handle problems on his own but learns to use aggression as a primary means of solving problems. In these violent video games the avatar of the player is often destroyed if the player fails to correctly navigate the animated situation. These games also display little portrayal of any realistic consequences of violence (Van Evra 78). In 2001 89% of video games were shown to have violence in them, while 79% of games rated E for everyone had some form of animated violence in which killing was rewarded and justified (78). The startling revelation that sanitized violence may have a pronounced impact on children is startling. This cast the realm of video games into an entirely new light. Even the most child-friendly video games seem to feature some aspect of violence. Comparative studies between older forms of media, such as television or film, and newer forms of media like video games has shown that video game violence exposure yields a significant unique positive association with violent behavior even after controlling for sex, age, game condition, and older violent media exposure, (Gentile 75). Although positive correlations between television and film have also been found, the correlation between violent video games and aggressive or violent behavior is the strongest. Arguments may be voiced that the studies run to reach the conclusion concerning the certainty of the causal effects of violent media in fostering aggression were flawed. This would still allow for an acknowledgment that there is a clear correlation between the two. There is a consensus among most researches that confirms the fact that there is a strong association

between viewing violence and behaving aggressively, (Van Evra 81). Those who would choose not to accept that causal relationship between media exposure and aggression are forced to at least acknowledge a correlation which allows the argument of this paper to hold water. Despite the indisputable effects of these forms of media in encouraging hyper masculine characteristics, namely aggression, there are measures that can be taken to reduce the effects. One obvious solution noted by Katherine Buckley and Douglas Gentile is merely to reduce as much as possible childrens and adolescents exposure to such violent games, (Buckley, Gentile 160). In their book Violent Video Games Effects on Children and Adolescents, Buckley and Gentile offer other less effective yet still viable options. An explicit talk with the child about the negative effects of media violence and an explanation that the aggressive solutions to interpersonal conflicts shown on the screen do not translate to the physical world. Other talks to help the child distinguish between fantasy and reality will also be helpful but no solution offers an equally effective alternative to reduced exposure. Some parents will try to play the violent game with their children and forgo the discussion. This, however, can cause more harm than good because such coplay without explicit discussions of harmful effects, inappropriateness of violent solutions in real life, and promotion of nonviolent alternatives is likely to be seen by child as endorsement of violent attitude and behaviors, (Buckley, Gentile 161). Reducing exposure is the best viable option for minimizing the negative impact of violent media on young boys. Studies have linked individual-level exposures with individual-level behaviors, and upon reduction of exposure the corresponding attributes appear to slowly fade

(Robinson 194). The media itself has evolved to become more violent which results in greater negative impacts on young viewers. A study discussed in the New York Times showed that between 1950 and 2012 violence in American film and television had more than doubled for the average viewing time. This increase in the violent content of media indicates that switching genres to avoid shows perceived as violent may not be a complete solution. Complete reduction of time spent in contact with the media is a more complete course of action and has the best chances of minimizing the effects of violent media on the child. Negative effects of media exposure may not have magnanimous impacts on the lives of individuals, but the growth of a generation of hyper masculine aggressive men may have a greater social impact. By pinpointing the sources for masculine influence in the lives of young boys it is a simple matter of replacing the influence with another source. Raised levels of aggression deteriorate the constructs of social conduct and reduce interactions to impulse and violence. Young boys need to learn to be properly masculine with interests in manners, wit, and achievement rather than lust, violence, and acquisition.

Works Cited Anderson, Craig Alan, Douglas A. Gentile, and Katherine E. Buckley. Violent Video Game Effects on Children and Adolescents Theory, Research, and Public Policy. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2007. Print.

Arthurs, Jane. Television and Sexuality Regulation and the Politics of Taste. Maidenhead, England : Open University Press, 2004. Print.

Feasey, Rebecca. Masculinity and Popular Television. Edinburgh : Edinburgh University Press, 2008. Print.

Ravitch, Diane, and Joseph P. Viteritti. Kid Stuff : Marketing Sex and Violence to America's Children. Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. Print.

Van Evra, Judith Page. Television and Child Development. Mahwah, N.J. : Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 2004. Print.

Walkerdine, Valerie. Children, Gender, Video Games : Towards a Relational Approach to Multimedia. Basingstoke England ; New York : Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. Print.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Surprising Way To A Stronger Marriage - How The Power of One Changes EverythingDocumento34 pagineThe Surprising Way To A Stronger Marriage - How The Power of One Changes EverythingSamantaNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Philippine Public Administration It S Nature and Evolution As Practice and DisciplineDocumento7 paginePhilippine Public Administration It S Nature and Evolution As Practice and DisciplineannNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Comelec Vs Quijano PadillaDocumento10 pagineComelec Vs Quijano PadillaJerome MoradaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Kurt Lewin's Three Phases Model of Learning To Training Process Within An Organisation.Documento7 pagineKurt Lewin's Three Phases Model of Learning To Training Process Within An Organisation.Winnie MugovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Kornet ''Contracting in China''Documento31 pagineKornet ''Contracting in China''Javier Mauricio Rodriguez OlmosNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- National University of Study and Research in Law: CoercionDocumento6 pagineNational University of Study and Research in Law: CoercionRam Kumar YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Tiangco v. LeogardoDocumento7 pagineTiangco v. LeogardoMrblznn DgzmnNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Personality Test Result - Free Personality Test Online at 123testDocumento17 paginePersonality Test Result - Free Personality Test Online at 123testapi-523050935Nessuna valutazione finora

- 73 People v. TemporadaDocumento62 pagine73 People v. TemporadaCarlota Nicolas VillaromanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Situation of Ethics and Discipline in Our Society and Its Importance in Life and Chemical IndustryDocumento6 pagineSituation of Ethics and Discipline in Our Society and Its Importance in Life and Chemical IndustryHaseeb AhsanNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- ACCO-20163 First QuizDocumento4 pagineACCO-20163 First QuizMarielle UyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- SyllabusDocumento12 pagineSyllabusChandan KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Short-Term Imprisonment in Malaysia An OverDocumento13 pagineShort-Term Imprisonment in Malaysia An Overlionheart8888Nessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Understanding ArgumentsDocumento8 pagineUnderstanding ArgumentsTito Bustamante0% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

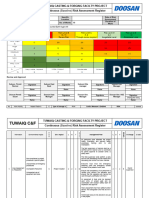

- RA 18 (Well Bore Using Excavator Mounted Earth Auger Drill) 2Documento8 pagineRA 18 (Well Bore Using Excavator Mounted Earth Auger Drill) 2abdulthahseen007Nessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- FATE - Tianxia - Arcana For The Deck of Fate (Blue)Documento4 pagineFATE - Tianxia - Arcana For The Deck of Fate (Blue)Sylvain DurandNessuna valutazione finora

- Cestui Qui TrustDocumento12 pagineCestui Qui TrustVincent J. Cataldi100% (1)

- Instructor Syllabus/ Course Outline: Page 1 of 5Documento5 pagineInstructor Syllabus/ Course Outline: Page 1 of 5Jordan SperanzoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Historical Background of State System & International Society & General ConceptsDocumento8 pagineHistorical Background of State System & International Society & General ConceptsGibzterNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 3 Ethical TheoriesDocumento9 pagineChapter 3 Ethical TheoriesMyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jdocs Framework v6 Final ArtworkDocumento65 pagineJdocs Framework v6 Final ArtworkRGNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Conciencia Emoción PDFDocumento22 pagineConciencia Emoción PDFdallaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fraud &sinkin Ships in MiDocumento13 pagineFraud &sinkin Ships in Miogny0Nessuna valutazione finora

- Part of Essay: Body Paragraph, Paragraphing, Unity and CoherenceDocumento3 paginePart of Essay: Body Paragraph, Paragraphing, Unity and CoherenceSari IchtiariNessuna valutazione finora

- PLM OJT Evaluation FormDocumento5 paginePLM OJT Evaluation FormAyee GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- An Intentionality Without Subject or ObjDocumento25 pagineAn Intentionality Without Subject or ObjHua SykeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Martin Luther King JR Rough DraftDocumento2 pagineMartin Luther King JR Rough Draftapi-247968908100% (2)

- I, Mario Dimacu-Wps OfficeDocumento3 pagineI, Mario Dimacu-Wps Officeamerhussienmacawadib10Nessuna valutazione finora

- Louis Althusser - The Only Materialist Tradition (Spinoza)Documento9 pagineLouis Althusser - The Only Materialist Tradition (Spinoza)grljadusNessuna valutazione finora

- InjunctionDocumento3 pagineInjunctionHamid AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)