Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Contra Right Action Theories OUTLINE

Caricato da

Carolyn ThompsonCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Contra Right Action Theories OUTLINE

Caricato da

Carolyn ThompsonCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A.

Outline It is impossible to formulate a useful theory of right action within the virtue theory framework ! To show this I will attempt to formulate one ! Hursthouse according to Johnson ! Hursthouses right action theory according to Johnson: V: An action A is right for S in circumstances C if and only if a completely virtuous agent would characteristically A in C. ! Either right-handed or left-handed (R)! Either we take it that S is a generic virtuous person, a virtuous saint, if you will, or (L)! S is the virtuous idealization of the individual in circumstances C ! Both are antithetical and wrong-headed to virtue theorys overarching approach and project ! Virtue theory, properly understood, simply isnt concerned with whether individual actions are right or wrong and does not nor should it provide or be able to provide a theory of right action. ! Both (R) and (L) miss this point and can be discarded on these grounds alone, however this may not convince everyone so secondary, more solid objections should be raised against both readings of Hursthouse according to Johnson. ! (R) This view is antithetical in the proper sense of the word because it is unconcerned with the individual performing the action whereas virtue theory begins with this concern. It is so generic that it does not take anything about the agent into account whereas with virtue theory everything hinges on the particularities of the individual. ! (L) The second is opposed in a less clear way: it demonstrates an extreme concern for who the individual is and in fact hinges on this, but still misses the target of virtue theory because it is in the end still primarily concerned with the action: any concern for the individual was only necessary for

Marcondes 2

the evaluation of the action, the evaluations foremost concern. Some will insist that virtue theory must provide a theory of right action, so below we will formulate this view, but only to show that a properly conceived theory of right action, while still inherently missing the point of virtue theory also comes out too complex, too obscurant, and too obtuse to be useful. ! Lets begin with more or less the theory (L) supports: ! M1: the right action for P in situation S is the action that the virtuous idealization of the individual, V, in S would take. ! It seems like even though V is founded in Ps individuality, V is not in any way P, assuming that P is not a perfectly virtuous person. ! Ignoring the problem that V may have never been put in whatever situation P is in due to Vs virtuousness, whatever action V takes is no longer informed by the individuality of Ps current state of being. That is, because P is not virtuous, certain things must play into the decision. ! Example: the decision to go out or not to go out on a Thursday night when you have an exam on Friday morning. ! Your virtuous, perfected version of yourself might say something like, sure, go out, relax, but dont drink too much and dont stay out too late so youll be able to take the exam in the morning. Imagine then, that V goes out. P, then, according to our formulation above can go out. In fact, going out is the moral imperative, in this situation (we can see that this is already absurd). ! So then P goes out, but unlike V, who has perfect temperance and moderation, P drinks too much and stays out until nal call, stumbles home, and sleeps through the exam. Then it seems like the virtuous thing for P to have done was just to not go out, but thats not what V, the virtuous ideal of P,

Marcondes 3

would have done. So theres this crucial dissonance here between what the ideal person does and what the non-ideal person should do. Consider instead M2 which takes limitations of the agent into consideration to account for the dissonance above: ! M2: the right action for P in situation S is the action that the virtuous idealization of the individual, V, would exhort P to take when V considers Ps limitations. This is playing into the idea that V has perfect reasoning and can actually place herself into her non-perfectlyvirtuous-selfs shoes. This move is sound because the virtuous person will supposedly be lling her function daccord Aristotles function argument that human function is acting in accord with reason. We can imagine that this includes being able to reason perfectly in such a priori, imagined situations. This moves us away from a paradigm of imitation (or, if youll allow it, habituation) and into one akin to exhortation. M2 gives P the ability to obtain an exhortation whereby V empathizes with the entirety of Ps situation, and more explicitly with Ps vicious character traits. In the example above, V might go out, but because V is not consideration the limitations of P, V exhorts P to stay in, reminding them of their track record in similar situations. ! This seems more akin to what Aristotle wants from us when he argues for the virtuous activity being the choosing of higher goods over lower goods. ! Going out is indeed a good, it would be fun, you might bond with some friends you never had with before, so on and so forth, but it is certainly more benecial for the individual that she stays in, choosing that good over the good of going out. In this situation then, staying in was the higher good and if it is chosen then a virtuous choice has been made. If it is not chosen, then even though going out is a good, it is a vicious choice because a higher

Marcondes 4

good has been foregone. But the limitations of P bear directly onto the goodness of either choice and this it is impossible for P to simply say that Vs actions or choices are always ones that reect the highest good in the situation because what is good for V is not always good for P who has limitations V necessarily does not share. ! In the end, however, even if we agree that M2 is a proper formulation of what a virtuous theory of right action would look like, we must still admit that it is completely unusable for the reasons Johnson gives. It is simply impossible for P to use M2 or any other theory of right action to decide what to do because P cannot imagine herself as V and then imagine, while still imagining herself as V consider all Ps limitations and then exhort herself, P, as V to do whatever is the highest good. One can see that even if this was a possibility it would be so obscurant as to be unusable. ! Why then did we just spend so much time on this question when we could have seen from the beginning that any theory of right action would be impossible for virtue theory? Because one must understand clearly that it is indeed impossible to the point of absurdity when one tries. Hopefully the obtuse nature of the above explication strikes the reader. The reason for this is that this theory of right action completely misses the point of virtue theory. Virtue theory has zero concern for whether an actions is right or wrong. In fact, virtue theory, properly understood, is completely compatible with moral antirealism (moral nihilism too). Virtue theory begs us to look away from the actions and to the actor through the lens of the action. That is to say, we should utilize what psychological (or psychoanalytic) information the actions provide to make value judgements about the character of the agent.

B.

Wolfs moral saints nd their usefulness here: they show that the lives led and the actions taken by moral saints, common-sense, utilitarian, and deontological, reect poorly on the agent. Wolf argues that the utilitarian moral saint suffers from Williams one-thought-too-many syndrome and deontological moral saints seem to care about morality in inhuman ways such that we begin to wonder that the deontological moral saint is lacking in some mental faculty. Susan Wolfs Moral Saints article shows that act-centered and right action moral theories do not produce desirable states of being.

Marcondes 5

! !

The common-sense rational saint ! The rational saint always maximizes the good or follows the categorical imperative often at the expense of their own happiness and projects ! They also perform moral actions for the sake of morality, not for the sake of the content of the actions ! Their motivation seems empty and inhuman The common-sense loving saint ! The loving saint performs moral actions because they enjoy them ! They forego all luxuries happily and inhumanly ! When one reects . . . on the Loving Saint easily and gladly giving up his shing trip or his stereo or his hot fudge sundae at the drop of the moral hat, one is apt to wonder not at how much he loves morality, but at how little he loves these other things. (Emphasis mine) Both of these saints do not look like types of people we would want to be. Neither is able to enjoy art, good food, family, etc. because they are constantly concerned with performing moral actions for the sake of those actions or because they love them. ! In the rst case, the rational, the person is completely ascetic: Nietzsche has argued well enough against such asceticism. She foregoes all personality: that is she rejects any opportunity to pursue family, friends, art, and so on because she is obsessed with serving others at the expense of herself. She thus never develops any sort of personality and is simply an empty not-even-merely-human automaton. This person experiences extreme alienation from themselves. ! In the second case, the loving, the person does not love helping others or serving them with their lives which would be a perfectly normal and human way of being moral (moral almost by accident, if you will) but rather loves morality as such and thus essentially hedonically performs moral actions. Thus, while her personality is fullled in her performance of moral actions she (a) does not perform them for reasons that seem genuine and (b) does not have what we would normally consider a human personality. This person experiences extreme alienation from normally human faculties. ! The loving saint seems to be missing a piece of perceptual machinery, of being blind to some of what the world has to offer. Thus, according to Wolf, the loving saint is in a sense less than human precisely because she so willingly abandons normal

Marcondes 6

pleasures in favor of ascetic morality. Wolfs evaluation of virtuous moral saints is inadequate ! The perfectly virtuous person is the person that has grasped eudaimonia which is happiness, ourishing, self-sufciency and fulllment. The eudaimonic individual is intensely human because they experience the whole range of human emotions and desires but have so shaped them that they are able to sustain happiness, ourishing and fulllment regardless of what happens. They are immovable from this position. ! Wolf disagrees, however: no matter how rich we make the life in which perfect obedience to this guide would result, we will have reason to hope that a person does not wholly rule and direct his life by the abstract and impersonal consideration that such a life would be morally good. ! However, it is precisely in virtue theory that we nd this hope fullled, of the rich life, but the rich life that the perfectly virtuous person lives is antithetical to both versions of common-sense morality and to the formal moral theory saints. ! This is only true because a crucial difference exists between common-sense morality and the two modern moral theories and virtue theory: the former are all three concerned with actions while the latter is rst and foremost concerned with the individual performing the actions. ! In the paradigm of virtue ethics we perform ethical actions because they serve to develop specic character traits that lend themselves to the promotion of the eudaimonic life. ! Virtue ethics begins with a consideration for personality, projects, the good life in general, and such things which we found the other moral saints lacking and then provides the framework within which one renes themselves to achieve these projects and the good life. What seem like moral actions, in this framework, ow only from virtuous personality and a personal desire to improve ones character for the sake of one's self and not moral actions themselves. Not, moral personality, rather morality in service to personality. We must emphasize that the difference that make virtue theory not fall to the problem of having one thought too many or impersonal saints is its concern for !

Marcondes 7

the agent and not the actions. We cannot even speak of virtue theory producing good actions because this implies that virtue theory is a theory of good action when in reality virtue theory is only concerned with the agent. If we focus completely on getting a virtuous agent then actions that seem like morally good ones will simply ow effortlessly from the virtuous person. Wolf is right that deontology and utilitarianism are poor universal guides for the individual seeking to live a healthy life; but then again, they never position themselves as such. Virtue ethics, on the other hand, is developed with this express purpose in mind. I will demonstrate in the next section why a theory of right action does not make sense within the virtue theory framework.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Sample Court Attendance Notice - PoliceDocumento1 paginaSample Court Attendance Notice - PoliceAlverastine AnNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- CSS Criminology NotesDocumento22 pagineCSS Criminology NotesM Faadi Malik75% (12)

- Women, Crime and Punishment: A Global View: Sushantika ChakravorttyDocumento7 pagineWomen, Crime and Punishment: A Global View: Sushantika ChakravorttySushantika ChakravorttyNessuna valutazione finora

- CRIMINAL LAW 1 REVIEWER Padilla Cases and Notes Ortega NotesDocumento110 pagineCRIMINAL LAW 1 REVIEWER Padilla Cases and Notes Ortega NotesrockaholicnepsNessuna valutazione finora

- Galgotias University: Saif Ali AnsariDocumento3 pagineGalgotias University: Saif Ali Ansarisaif aliNessuna valutazione finora

- 49 - Consti2-G.R. No. L-68955 P V Burgos - DigestDocumento4 pagine49 - Consti2-G.R. No. L-68955 P V Burgos - DigestOjie SantillanNessuna valutazione finora

- Digest Cases (Crim)Documento3 pagineDigest Cases (Crim)CentSeringNessuna valutazione finora

- Leg Res Case BriefDocumento5 pagineLeg Res Case BriefKaira CarlosNessuna valutazione finora

- 010 - A Note On The Official Secrets Act, 1963Documento3 pagine010 - A Note On The Official Secrets Act, 1963kamal jatNessuna valutazione finora

- SISTEM PEMIDANAAN EDUKATIF TERHADAP ANAK HendyDocumento22 pagineSISTEM PEMIDANAAN EDUKATIF TERHADAP ANAK HendyiskandarNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminology Project PDFDocumento12 pagineCriminology Project PDFMohammad Ziya AnsariNessuna valutazione finora

- PP vs. TabacoDocumento2 paginePP vs. Tabacojim schaultzNessuna valutazione finora

- Tyrone Scott RotatedDocumento4 pagineTyrone Scott RotatedJeremy TurnageNessuna valutazione finora

- Transes ETHICSDocumento10 pagineTranses ETHICSAthaliah WalterNessuna valutazione finora

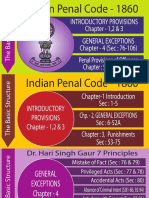

- Introductory Provisions Chapter - 1,2 & 3 General Exceptions Chapter - 4 (Sec: 76-106) Penal Provisions of Offences Chapter: 5-23 (107-511)Documento5 pagineIntroductory Provisions Chapter - 1,2 & 3 General Exceptions Chapter - 4 (Sec: 76-106) Penal Provisions of Offences Chapter: 5-23 (107-511)PNR AdminNessuna valutazione finora

- Booking Report 7-21-2021Documento3 pagineBooking Report 7-21-2021WCTV Digital TeamNessuna valutazione finora

- Joint LiabilityDocumento8 pagineJoint LiabilityAnonymous hJ5SLZAuaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sept 2016 - Investigative Professionals W CertDocumento45 pagineSept 2016 - Investigative Professionals W CertDivya ThomasNessuna valutazione finora

- New Essays On The Normativity of LawDocumento336 pagineNew Essays On The Normativity of LawJuan David Oceguera100% (1)

- Handbook of Transnational Crime and Justice - (Chapter 3 Measuring and Researching Transnational Crime)Documento16 pagineHandbook of Transnational Crime and Justice - (Chapter 3 Measuring and Researching Transnational Crime)SEUNGWANderingNessuna valutazione finora

- Peralta vs. Dir. of PrisonsDocumento2 paginePeralta vs. Dir. of PrisonsJen100% (7)

- The History of Heavy Metal Music & The Metal SubcultureDocumento41 pagineThe History of Heavy Metal Music & The Metal SubcultureDaniel TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- People of The Philippines v. Rustico Bartolini GR 179498, August 3, 2010Documento2 paginePeople of The Philippines v. Rustico Bartolini GR 179498, August 3, 2010Hemsley Battikin Gup-ayNessuna valutazione finora

- 40 Cases Final PDFDocumento86 pagine40 Cases Final PDFaltizen_maryluzNessuna valutazione finora

- Concept Map Ethics Gned 02Documento2 pagineConcept Map Ethics Gned 02JOHN JOMIL RAGASANessuna valutazione finora

- Rape Is A Culture-A Need For Change: Key Words: Rape, Victim BlamingDocumento7 pagineRape Is A Culture-A Need For Change: Key Words: Rape, Victim BlamingDevesha SarafNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethics and Moral Philosophy - General Introduction - 2020 - Lecture 4Documento3 pagineEthics and Moral Philosophy - General Introduction - 2020 - Lecture 4BlueBladeNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminal Law Memory AidDocumento95 pagineCriminal Law Memory AidLeslie TanNessuna valutazione finora

- Kishore Kandalai - 500 - Module - 1 - 21jan2011Documento24 pagineKishore Kandalai - 500 - Module - 1 - 21jan2011Kishore KandalaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Name: Soumya Mukherjee Course: B.Sc. Statistics (Honours) Semester: 1 ROLL NO.: 449 Topic: Assignment For Foundation CourseDocumento6 pagineName: Soumya Mukherjee Course: B.Sc. Statistics (Honours) Semester: 1 ROLL NO.: 449 Topic: Assignment For Foundation Coursepontas97Nessuna valutazione finora