Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Courtney v. Danner Brief in Opposition

Caricato da

joshblackmanCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Courtney v. Danner Brief in Opposition

Caricato da

joshblackmanCopyright:

Formati disponibili

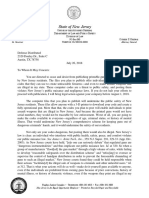

No.

13-1064

In The Supreme Court Of The United States

JAMES COURTNEY AND CLIFFORD COURTNEY,

PETITIONERS,

v. DAVID DANNER, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS CHAIRMAN AND COMMISSIONER OF THE WASHINGTON UTILITIES AND TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION, ET AL.,

RESPONDENTS.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT RESPONDENTS BRIEF IN OPPOSITION ROBERT W. FERGUSON Attorney General NOAH G. PURCELL Solicitor General JAY D. GECK Deputy Solicitor General FRONDA C. WOODS Assistant Attorney General Counsel of Record 1125 Washington Street SE Olympia, WA 98504-0100 360-586-2644 fronda.woods@atg.wa.gov

QUESTION PRESENTED The State of Washington regulates ferry services within the state and requires a certificate of public convenience and necessity before a commercial ferry service may operate. Does the Privileges or Immunities Clause prohibit the states from requiring such a certificate to regulate commercial ferry services?

ii

PARTIES Petitioners James and Clifford Courtney were the appellants in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The respondents in the Ninth Circuit were Jeffrey Goltz, then-chairman and commissioner of the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission (WUTC); Patrick Oshie, thencommissioner of the WUTC; Philip Jones, commissioner of the WUTC; and David Danner, then-executive director of the WUTC, in their official capacities. Since the appeal began, Oshie has resigned from the WUTC, Danner has been appointed its chairman, and Steven King has been appointed its executive director. Accordingly, pursuant to Rule 35.3, the respondents in this Court are David Danner, chairman and commissioner; Jeffrey Goltz, commissioner; Philip Jones, commissioner; and Steven King, executive director, in their official capacities.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................... 1 REASONS WHY THE COURT SHOULD DENY THE PETITION .............................................. 6 A. There Is No Conflict Regarding Whether There Is A Federally Secured Privilege To Avoid State Ferry Regulation ........................................................... 8 There Is No Widespread Uncertainty Or Judicial Paralysis That Requires Review Of Petitioners Claim ........................... 14 This Case Is Not A Good Vehicle To Give Meaningful Guidance On The Privileges Or Immunities Clause ..................... 15

B.

C.

CONCLUSION .......................................................... 19

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Butchers Union Slaughter-House & LiveStock Landing Co. v. Crescent City Live-Stock Landing & Slaughter-House Co. 111 U.S. 746 (1884) ..................................................... 10 Canadian Pac. Ry. Co. v. United States 73 F.2d 831 (9th Cir. 1934)........................................ 11 Chavez v. Arte Publico Press 204 F.3d 601 (5th Cir. 2000) ..................................... 15 Conway v. Taylors Exr 66 U.S. (1 Black) 603 (1861) ................................ 11, 18 Evans v. Romer 882 P.2d 1335 (Colo. 1994) ........................................ 14 Gloucester Ferry Co. v. Pennsylvania 114 U.S. 196 (1885) ..................................................... 10 Kitsap Cnty. Transp. Co. v. Manitou Beach-Agate Pass Ferry Assn 30 P.2d 233 (Wash. 1934) .......................................... 12 Lutz v. City of York, Pa. 899 F.2d 255 (3d Cir. 1990) ....................................... 15 McDonald v. City of Chicago, Ill. 130 S. Ct. 3020 (2010)....................................... 7, 13, 16

Merrifield v. Lockyer 547 F.3d 978 (9th Cir. 2008) ..................................... 15 Mills v. Cnty. of St. Clair 49 U.S. (8 How.) 569 (1850)................................. 11, 18 New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann 285 U.S. 262 (1932) ..................................................... 11 Patterson v. Wollmann 67 N.W. 1040 (N.D. 1896) .......................................... 12 Pollack v. Duff 958 F. Supp. 2d 280 (D.D.C. 2013) .......................... 15 Port Richmond & Bergen Point Ferry Co. v. Bd. of Chosen Freeholders 234 U.S. 317 (1914) ..................................................... 10 R.R. Comm'n of Texas v. Pullman Co. 312 U.S. 496 (1941) ................................................... 4, 6 Romer v. Evans 517 U.S. 620 (1996) ..................................................... 14 Saenz v. Roe 526 U.S. 489 (1999) ...................................... 7, 12, 15-16 SlaughterHouse Cases 83 U.S. 36 (1873).......................................... 5-7, 9-10, 14 Starin v. Mayor of New York 115 U.S. 248 (1885) ..................................................... 10

vi

State Highway Bd. v. Willcox 149 S.E. 182 (Ga. 1929) .............................................. 11 Tri-State Ferry Co. v. Birney 31 S.W.2d 932 (Ky. 1930)........................................... 12 Vallejo Ferry Co. v. Solano Aquatic Club 131 P. 864 (Cal. 1913) ................................................. 11 Washington State Grange v. Washington State Republican Party 552 U.S. 442 (2008) ................................................ 18-19 Williamson v. Lee Optical of Oklahoma, Inc. 348 U.S. 483 (1955) ..................................................... 13 Statutes 16 U.S.C. 90c-1(e) ........................................................... 2 28 U.S.C. 2201 ................................................................. 4 42 U.S.C. 1983 ................................................................. 4 Wash. Rev. Code 81.84.010(1) ..................................... 2 Wash. Rev. Code 81.84.020(1) ..................................... 2 Wash. Rev. Code 81.84.020(2) ..................................... 2 Rules Rule 10 ................................................................................. 1 Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6) ..................................................... 4

vii

Other Authorities James W. Ely, Jr., To Pursue any lawful Trade or Avocation: The Evolution of Unenumerated Economic Rights in the Nineteenth Century, 8 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 917 (Sept. 2006) ..................... 17 Jeffrey D. Jackson, Be Careful What You Wish For: Why Mcdonald v. City of Chicagos Rejection of the Privileges or Immunities Clause May Not Be Such A Bad Thing for Rights, 115 Penn St. L. Rev. 561, 578 (Winter 2011) ........ 17 Josh Blackman & Ilya Shapiro, Keeping Pandoras Box Sealed: Privileges or Immunities, The Constitution In 2020, and Properly Extending the Right to Keep and Bear Arms to the States, 8 Geo. J.L. & Pub. Poly 1 (Winter 2010)................ 17 Randy E. Barnett, Does the Constitution Protect Economic Liberty, 35 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Poly 5 (Winter 2012) ........... 17 WUTC, Appropriateness of Rate and Service Regulation of Commercial Ferries Operating on Lake Chelan (Jan. 11, 2010), available at http://www.wutc.wa.gov/ rms2.nsf/177d98baa5918c7388256a550064a6 1e/aa3eabfb83b1571d8825792e0065383a!Ope nDocument ...................................................................... 4

INTRODUCTION A petition for a writ of certiorari will be granted only for compelling reasons. Rule 10. None is present here. Petitioners seek to operate a ferry service on a lake in central Washington. Washington regulates ferry services, a state prerogative recognized for centuries. Petitioners cite no case, ever, that has held such state regulation violates the Fourteenth Amendment. On the contrary, this Court has long recognized that states possess this authority. Petitioners also fail to explain what pressing issue of national importance is presented by the court of appeals narrow, well-reasoned opinion. Petitioners claim judicial paralysis as to the Privileges or Immunities Clause. Pet. 2. The reality, however, is consistent, emphatic judicial rejection of petitioners arguments. Moreover, even if the Court wishes to revisit the scope of privileges or immunities, this case is a terrible vehicle to do so. Petitioners seek review of their facial challenge to Washingtons regulations, so those regulations must be upheld if susceptible to any constitutional application. Under that standard, the regulations plainly survive, offering no room for the Court to clarify or revisit anything about the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court should therefore deny certiorari. STATEMENT OF THE CASE 1. Respondents are the executive director and members of the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission (WUTC). Under long-

established state law, a commercial ferry may not operate any vessel or ferry for the public use for hire between fixed termini or over a regular route upon the waters within [Washington] . . . without first applying for and obtaining from the [WUTC] a certificate declaring that public convenience and necessity require such operation. Wash. Rev. Code 81.84.010(1). To obtain the required certificate, a potential operator must show that its proposed operation is required by public convenience and necessity and that it has the financial resources to operate the proposed service for at least twelve months. Wash. Rev. Code 81.84.020(1), (2). If the location is already served by a commercial ferry, no certificate may be granted unless the applicant shows that the existing certificate holder: [(a)] has failed or refused to furnish reasonable and adequate service[; (b)] has failed to provide the service described in its certificate or tariffs after the time allowed to initiate service has elapsed[;] or [(c)] has not objected to the issuance of the certificate as prayed for. Wash. Rev. Code 81.84.020(1). 2. Petitioners live in a small community named Stehekin on the northwest end of Lake Chelan in central Washington. Petitioners operate businesses in Stehekin, which is a popular recreation area. Stehekin is accessible only by boat, plane, or foot. See 16 U.S.C. 90c-1(e). In 1997, petitioner James Courtney applied for a certificate to operate a ferry. The WUTC denied the commercial ferry certificate after finding that the existing operator provided reasonable and adequate service, that the proposed service would affect the existing operator, and that petitioner did not satisfy the financial

responsibility requirement. Petitioner did not appeal the findings that led to denial of a certificate in 1998, and petitioners have never again applied for a ferry certificate. In 2006, petitioners began to explore whether a charter or shuttle vessel service would be exempt from the certificate requirement. In 2008, a WUTC official told petitioners that, in the opinion of WUTC staff, a boat for hire to serve petitioners businesses would require a certificate. The WUTC official, however, also told petitioners that they could seek a declaratory ruling on the requirement of a certificate. Or, petitioners could proceed with operations and potentially be subject to the WUTC initiating a classification proceeding to determine if a certificate is required for a charter or shuttle boat transportation service. Dissatisfied with these options, petitioners made requests to state legislators and the governor, after which the legislature directed the WUTC to conduct a study on the regulation of commercial ferry services on Lake Chelan. The WUTC issued the report in January 2010 and concluded that Lake Chelan Boat Company was providing satisfactory service and recommended that there be no change to the existing laws and regulations. The WUTC report noted that there could be flexibility under the existing law to permit some competition by exempting certain services from the certificate requirement, provided that any such service would

not significantly threaten the existing certificate holders business.1 3. In October 2011, petitioners sued for declaratory and injunctive relief pursuant to 42 U.S.C. 1983 and 28 U.S.C. 2201. They claimed the ferry certificate law abridged a right to use navigable waters of the United States that was protected by the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The district court dismissed their complaint under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). The court concluded that even if a right to use navigable waters was a Fourteenth Amendment right, there was no right to operate a commercial ferry service open to the public[.] App. 46. The court also ruled that petitioners did not have a ripe claim to examine charter or shuttle boat transportation services on Lake Chelan for patrons of their businesses, as they had never sought a formal ruling from the WUTC as to whether such services would require a certificate. For the same reason, the court also abstained from addressing this second claim pursuant to Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312 U.S. 496 (1941). 4. A unanimous court of appeals affirmed, but modified the ruling regarding Pullman Co. abstention. The court of appeals agreed that even if the Privileges or Immunities Clause encompasses a

1 WUTC, Appropriateness of Rate and Service Regulation of Commercial Ferries Operating on Lake Chelan (Jan. 11, 2010), available at http://www.wutc.wa.gov/ rms2.nsf/177d98baa5918c7388256a550064a61e/aa3eabfb83b15 71d8825792e0065383a!OpenDocument.

federal right to use the navigable waters of the United States, any such right does not protect petitioners use of Lake Chelan to operate a commercial public ferry free from the certificate requirement. App. 14-15. The court of appeals examined the Slaughter House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873), at some length. The court of appeals recognized that Slaughter-House did not attempt to define the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States. Rather, the SlaughterHouse majority suggested only that such privileges might include a right to use the navigable waters of the United States, however they may penetrate the territory of the several States[.] Id. at 79 (emphasis added). The court of appeals explained why this dicta in Slaughter-House did not aid petitioners claim. Petitioners claim was about far more than navigation on waters of the United States. While navigation of Lake Chelan is a necessary component . . . it is neither sufficient to achieve their purpose nor the cause of their dissatisfaction. App. 17. The actual privilege that petitioners sought was to operate a commercial ferry for passengers without application of Washingtons ferry certificate requirements. The court of appeals concluded that it was exceedingly unlikely that the reference to navigation in SlaughterHouse indicated that states, in the Fourteenth Amendment, lost their historic authority to regulate public ferries. App. 17. The court noted that even the dissenting justices in Slaughter-House affirmed state power to grant an exclusive privilege to private parties to operate a public ferry. App. 18 (citing Slaughter-House, 83

U.S. at 88 (Field, J., dissenting)); see also SlaughterHouse, 83 U.S. at 120-21 (Bradley, J., dissenting). Next, the court of appeals rejected petitioners view of the scope of the Privileges or Immunities Clause described in Slaughter-House. SlaughterHouse clearly held that the Privileges or Immunities Clause protects only those rights that are of a federal character. Operating a ferry is not inherently federal in character. Rather, the states retained a vital interest in regulating passenger ferries wellestablished in case law. And, nothing in federal law contemplated any need to preempt state ferry regulations. Last, the court of appeals modified the abstention ruling for the alternative claim of a right to offer boat services to patrons of specific businesses. Petitioners had standing to make that claim, but the claim would be rendered moot if the WUTC or Washington Supreme Court concluded that no certificate is required for the proposed charter or shuttle boat service. Therefore, the federal courts could not address that claim under the abstention doctrine in Pullman Co. The court of appeals instructed the district court to retain jurisdiction if petitioners were going to pursue their claim that the certificate requirement does not apply to a charter or shuttle boat service. REASONS WHY THE COURT SHOULD DENY THE PETITION Petitioners ask this Court to examine whether the Fourteenth Amendment creates a never-beforerecognized right to ignore state licensing requirements for intrastate commercial ferry

services. The question presented falls short of the Courts standards for granting certiorari. First, the courts are not in conflict over the question. No court has ever recognized the unusual privilege alleged by petitioners. Indeed, this Court and others have uniformly recognized state authority to regulate ferries throughout American history. Second, the opinion of the court of appeals creates no tension with this Courts statements on the Privileges or Immunities Clause. Nothing in Saenz (infra p. 12), McDonald (infra p. 13), or Slaughter-House supports petitioners claim that the Fourteenth Amendment contains a privilege to operate commercial ferries without state regulation. Third, petitioners theory that certiorari is needed to unlock paralysis in lower courts with regard to privileges or immunities is meritless. Petitioners selective review of cases does not show a paralyzed judiciary unable to resolve arguments about constitutional rights. The reality, unfortunately for petitioners, is an unbroken line of casesincluding from this Courtrejecting arguments like theirs that seek to render state regulation of economic activity unconstitutional. Decisive rejection is not paralysis. Finally, this case is a poor vehicle to explore privileges or immunities. Petitioners seek review of their facial challenge to state regulation of commercial ferries. On such a challenge, Washingtons law would have to be upheld if susceptible to any constitutional application, a standard obviously satisfied here. Thus, even if the Court wishes to revisit the scope of privileges or

immunities, this case is inappropriate to consider that issue. A. There Is No Conflict Regarding Whether There Is A Federally Secured Privilege To Avoid State Ferry Regulation

1. In analyzing potential conflict, it is important to be clear about the true nature of the privilege petitioners claim. Petitioners say they are asserting a right to use the navigable waters of the United States. Amici describe it as a right to use federal navigable waterways. Neither is accurate. As the court of appeals explained, the actual privilege at stake is a ferry operation privilege, not a broad navigation privilege. App. 17. Petitioners are free to travers[e] Lake Chelan in a private boat for private purposes. App. 21. At the end of the day, the state legislation the Courtneys challenge is narrow in scope, merely restricting the operation of commercial public ferries to those who obtain a [public convenience and necessity] certificate. App. 21. Petitioners and amici also mischaracterize the court of appeals dicta regarding economic issues. The court did not issue a ruling that eliminates economic interests from the protection of the Privileges or Immunities Clause, as petitioners and amici argue. The phrase economic concerns appears in the courts opinion only once, as part of an explanation of the nature of petitioners claim and the absence of case law supporting it. App. 18-19. What the court of appeals actually held was that the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment does not protect a right to operate a public ferry on Lake Chelan[.] App. 22.

2. No court has ever held or even hinted that operating a public ferry on a lake in the middle of a state is a right of national citizenship. That is because this Court and others have always understood intrastate ferries to be the prerogative of state and local authorities, as the court of appeals recognized. App. 19-20. The majority and both of the dissents in Slaughter-House confirm that understanding. The Slaughter-House majority recognized that laws which respect turnpike roads, ferries, etc., are component parts of the state police power. Slaughter-House, 83 U.S. at 63 (quoting Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1, 203 (1824)). Dissenting Justice Field agreed: It is the duty of the government to provide suitable roads, bridges, and ferries for the convenience of the public; and if it chooses to devolve this duty to any extent, or in any locality, upon particular individuals or corporations, it may of course stipulate for such exclusive privileges connected with the franchise as it may deem proper, without encroaching upon the freedom or the just rights of others. Id. at 88 (Field, J., dissenting); App. 18. Dissenting Justice Bradley also agreed: It has been suggested that [the 1624 Statute of Monopolies] was a mere legislative Act, and that the British Parliament, as well as our own Legislatures, have frequently disregarded it by granting exclusive privileges for erecting ferries, railroads, markets and other establishments of a public kind. It

10

requires but a slight acquaintance with legal history to know that grants of this kind of franchises are totally different from the monopolies of commodities or of ordinary callings or pursuits. These public franchises can only be exercised under authority from the government, and the government may grant them on such conditions as it sees fit. Slaughter-House, 83 U.S. at 120-21 (Bradley, J., dissenting). Rejection of the privilege claimed by petitioners, therefore, presents no conflict with Slaughter-House. Other decisions of this Court, both before and after Slaughter-House, confirm that ferries on internal waters are the prerogative of state and local governments. Port Richmond & Bergen Point Ferry Co. v. Bd. of Chosen Freeholders, 234 U.S. 317, 321 (1914) (tracing to English common law states practice of granting franchises for ferries wholly intrastate); Starin v. Mayor of New York, 115 U.S. 248 (1885) (whether city had exclusive right to establish ferries over public waters entirely within one state was a matter of state, not federal, law); Gloucester Ferry Co. v. Pennsylvania, 114 U.S. 196, 215 (1885) (The power of the States to regulate matters of internal police includes the establishment of ferries[.]); Butchers Union Slaughter-House & Live-Stock Landing Co. v. Crescent City Live-Stock Landing & Slaughter-House Co., 111 U.S. 746, 763 (1884) (Bradley, J., concurring) ([A]n exclusive right to use franchises, which could not be exercised without legislative grant, may be given; such as that of constructing and operating public works, railroads, ferries, etc.); Conway v. Taylors Exr, 66

11

U.S. (1 Black) 603, 635 (1861) (since before the Constitution had its birth, the States have exercised the power to establish and regulate ferries); Mills v. Cnty. of St. Clair, 49 U.S. (8 How.) 569, 581 (1850) (The parties respectively assume, and so the court below held, that the establishment and regulation of ferries across navigable streams is a subject within the control of the government, and not matter of private right; and that the government may exercise its powers by contracting with individuals. We deem this general principle not open to controversy[.]); see New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, 303 (1932) (Brandeis, J., dissenting) (Every citizen has the right to navigate a river or lake, and may even carry others thereon for hire. But the ferry privilege may be made exclusive in order that the patronage may be sufficient to justify maintaining the ferry service[.]). Petitioners claim challenges this unbroken line of authority from this Court. 4. There is no uncertainty or conflict among lower courts with regard to a privilege to avoid state regulation of commercial ferries. Decades of state and federal court decisions confirm that establishing and regulating ferries is the prerogative of state and local governments. E.g., Canadian Pac. Ry. Co. v. United States, 73 F.2d 831, 833 (9th Cir. 1934) (explaining that, in the United States, ferries are established by the legislative authority of states); Vallejo Ferry Co. v. Solano Aquatic Club, 131 P. 864 (Cal. 1913) (affirming injunction against operation of competing ferry); State Highway Bd. v. Willcox, 149 S.E. 182, 185 (Ga. 1929) (The right to establish and maintain a public ferry is a franchise, which, in this State, can only be

12

granted by the proper county authorities. (Internal quotation marks omitted.)); Tri-State Ferry Co. v. Birney, 31 S.W.2d 932 (Ky. 1930) (affirming injunction against operation of competing ferry); Patterson v. Wollmann, 67 N.W. 1040, 1044 (N.D. 1896) (citing Justice Fields Slaughter-House dissent in holding that citizens have no natural right to maintain a public ferry); Kitsap Cnty. Transp. Co. v. Manitou Beach-Agate Pass Ferry Assn, 30 P.2d 233, 234 (Wash. 1934) (state commercial ferry law is but an exercise of the power of the state, recognized and exercised from time immemorial, to control travel over and on its navigable streams and waters). The petitioners do not and cannot identify a single judicial holding that supports the extraordinary privilege they claim to avoid state ferry regulation. 5. Saenz v. Roe, 526 U.S. 489 (1999), presents no conflict or tension with the court of appeals ruling that the Fourteenth Amendment does not protect a commercial ferry operation from application of state law. The Saenz Court reaffirmed that the Privileges or Immunities Clause ensures each citizen a right to become a citizen of any state of the Union. Id. at 502-03 (finding that the Clause protects the right of the newly arrived citizen to the same privileges and immunities enjoyed by other citizens of the same State). Saenz found that this right has always been common ground in disputes over the scope of the clause, id. at 503, and that it could not be limited by a states discriminatory classification of newly arrived citizens to deny public benefits, id. at 505.

13

Petitioners claim no real conflict with Saenz, but cite a law review article criticizing the decision for failing to fully define privileges or immunities and instead simply holding that the right to travel is encompassed by that definition. Pet. 22. But refusing to go beyond the question presented is not typically viewed as a judicial failure. And even if the Court had provided a full description of every privilege and immunity, it plainly would not have included the right petitioners seek: to operate a commercial ferry on intrastate waters without state regulation. 6. The court of appeals decision also presents no tension with McDonald v. City of Chicago, Ill., 130 S. Ct. 3020 (2010). There, the petitioners asked the Court to hold that Second Amendment rights were among the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States. Id. at 3028. The Court declined the invitation to approach incorporation of Bill of Rights guarantees in this way and relied on established case law allowing incorporation under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Id. at 3031. The Courts decision relied on the conclusion that an individual right to bear arms was deeply rooted in this Nations history and tradition. Id. at 3036. That holding presents no conflict with this case, because there is no deeply rooted history or tradition of operating commercial ferries free of state licenses. See supra at *__ (citing decisions of this Court recognizing state authority over intrastate ferries); see also, e.g., Williamson v. Lee Optical of Oklahoma, Inc., 348 U.S. 483, 488 (1955) (The day is gone when this

14

Court uses the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to strike down state laws, regulatory of business and industrial conditions, because they may be unwise, improvident, or out of harmony with a particular school of thought.). 7. In short, petitioners can show no conflict and inaccurately describe the issues they ask the Court to address. Their claim would require the Court to completely rewrite Slaughter-House, to reexamine a century of case law concerning state regulation of commercial ferries, and to find a preemptive federal right to operate commercial ferries. B. There Is No Widespread Uncertainty Or Judicial Paralysis That Requires Review Of Petitioners Claim

Petitioners and their amici implicitly concede that there is no conflict in the courts as to the question presented. But they claim that the absence of conflict should be interpreted as widespread uncertainty or judicial paralysis. Pet. 14. The petitions selective quotations do not demonstrate any type of judicial paralysis or uncertainty that would be cured by review of this case. For example, petitioners cite the dissent in Evans v. Romer, 882 P.2d 1335 (Colo. 1994). Pet. 28. But discrimination against petitioning the government was addressed by this Court in Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996), and the issue raised by that dissent cannot be addressed in this case about

15

ferry certificates. Petitioners cite a district court decision in Pollack v. Duff, 958 F. Supp. 2d 280, 288 (D.D.C. 2013), where the court distinguished Saenz because government did not impose a penalty for relocating in a new state. That opinion expressed no difficulty in applying Saenz. Nor is there evidence of judicial confusion in Merrifield v. Lockyer, 547 F.3d 978, 983 (9th Cir. 2008), where the court rejected a claim that a right to pursue ones occupation preempts state regulation. Chavez v. Arte Publico Press, 204 F.3d 601, 608 (5th Cir. 2000), also does not support petitioners point. The opinion merely criticizes a litigant for making an untimely argument about whether a federal law was an exercise of power to enforce the Privileges or Immunities Clause. Finally, a twenty-five-year-old case about a right to travel is immaterial here; it was written long before Saenz addressed that subject. Lutz v. City of York, Pa., 899 F.2d 255, 264 (3d Cir. 1990). If the type of uncertainty cited by petitioners and their amici justifies certiorari, it would support certiorari for any legal theory consistently rejected by lower courts because of the absence of authority. C. This Case Is Not A Good Vehicle To Give Meaningful Guidance On The Privileges Or Immunities Clause

1. Petitioners claim this case would be a good vehicle to provid[e] guidance for . . . interpretation of Fourteenth Amendment Privileges or Immunities. Pet. 34 (second alteration in

16

original). Petitioners are mistaken. Their facial challenge would inevitably fail without the need for detailed exploration of the scope of the clause, and their constitutional theories cannot be addressed without confronting the same problems that arose when the Privileges or Immunities Clause was raised in McDonald. First, as petitioners admit (Pet. 36), stare decisis weighed heavily against announcing a new constitutional theory in McDonald. But stare decisis is equally weighty here because of the numerous cases upholding this and similar exercises of state authority, and because of public reliance on this state power. Second, petitioners recognize there was no legal or scholarly consensus to support the step the Court rejected in McDonald. Pet. 37. That is no different here. There is no legal or scholarly consensus or even debate on a privilege to operate a commercial ferry as claimed by petitioners. Third, petitioners protest that their case is not a Pandoras Box, suggesting it is akin to the right to travel analyzed in Saenz. Pet. 38. But the right to travel and establish residency was well-established; as the Saenz Court said, it has always been common ground. Saenz, 526 U.S. at 503. No such right is at issue here. To the contrary, an individual right to avoid state ferry certificate laws would open a Pandoras Box regarding state powers to regulate. Moreover, that Pandoras Box is the avowed intent of numerous articles cited by petitioners and authored

17

by their amici. E.g., Randy E. Barnett, Does the Constitution Protect Economic Liberty, 35 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Poly 5 (Winter 2012); Josh Blackman & Ilya Shapiro, Keeping Pandoras Box Sealed: Privileges or Immunities, The Constitution In 2020, and Properly Extending the Right to Keep and Bear Arms to the States, 8 Geo. J.L. & Pub. Poly 1 (Winter 2010); James W. Ely, Jr., To Pursue any Lawful Trade or Avocation: The Evolution of Unenumerated Economic Rights in the Nineteenth Century, 8 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 917 (Sept. 2006); see also Jeffrey D. Jackson, Be Careful What You Wish For: Why McDonald v. City of Chicagos Rejection of the Privileges or Immunities Clause May Not Be Such A Bad Thing for Rights, 115 Penn St. L. Rev. 561, 578 (Winter 2011) ([T]he real driving force in the argument over privileges or immunities and due process has to do with unenumerated rights, their protection, and possible expansion.). 2. This case is also a poor vehicle because petitioners pursue a facial challenge to the certificate requirement. Petitioners did not apply for a certificate during the decade preceding this lawsuit. Petitioners, therefore, claimed there was no possible application of the certificate law that would not violate the alleged constitutional privilege. See Compl. 113, 119. The Courts review would be curtailed by the facial nature of the challenge. The Court disfavors facial challenges that rest on speculation and require premature

18

interpretation of statutes on the basis of factually barebones records. Washington State Grange v. Washington State Republican Party, 552 U.S. 442, 450 (2008) (internal quotation marks omitted). These twin concerns exist in this case. The certificate law has not been applied. Therefore, this Court would be called on to interpret and speculate about how state law would be applied to fact-bound issues like whether there is reasonable and adequate current ferry service. As a facial challenge, the Court would need to reject the petitioners rhetoric that assumes the state is inappropriately granting a monopoly. Instead, petitioners would need to show that no set of circumstances exists under which the [certificate requirement] would be valid. Id. at 449. Petitioners cannot possibly make such a showing given that states have issued ferry certificates since before the Constitution had its birth, Conway, 66 U.S. (1 Black) at 635, and this general principle [is] not open to controversy, Mills, 49 U.S. (8 How.) at 581. Moreover, a facial challenge is contrary to the principle of judicial restraint that courts should neither anticipate a question of constitutional law in advance of the necessity of deciding it nor formulate a rule of constitutional law broader than is required by the precise facts to which it is to be applied. Washington State Grange, 552 U.S. at 450 (internal quotation marks omitted). This concern applies here, because the petition asks the Court to evaluate

19

rules for preemption of ferry certificate laws in the abstract. Finally, a facial challenge prevent[s] laws embodying the will of the people from being implemented in a manner consistent with the Constitution. Washington State Grange, 552 U.S. at 451. If there is a need to address ferry certificate laws, the laws should be examined after application to a particular set of facts by an expert state agency. CONCLUSION The petition should be denied. RESPECTFULLY SUBMITTED. ROBERT W. FERGUSON Attorney General NOAH G. PURCELL Solicitor General JAY D. GECK Deputy Solicitor General FRONDA C. WOODS Assistant Attorney General Counsel of Record 1125 Washington Street SE Olympia, WA 98504-0100 360-586-2644

April 25, 2014

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- No. 19-10011 United States Court of Appeals For The Fifth CircuitDocumento33 pagineNo. 19-10011 United States Court of Appeals For The Fifth CircuitjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- House of Representatives - Motion To Intervene - Texas v. USDocumento27 pagineHouse of Representatives - Motion To Intervene - Texas v. USjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- District of Columbia Et Al v. Trump OpinionDocumento52 pagineDistrict of Columbia Et Al v. Trump OpinionDoug MataconisNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- DOJ MTD - Maryland v. TrumpDocumento78 pagineDOJ MTD - Maryland v. Trumpjoshblackman100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- East Bay ECF 27 TRO OppositionDocumento36 pagineEast Bay ECF 27 TRO OppositionjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- 3-D Printed Gun Restraining OrderDocumento7 pagine3-D Printed Gun Restraining Orderjonathan_skillingsNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Maryland v. Trump - Interlocutory AppealDocumento36 pagineMaryland v. Trump - Interlocutory Appealjoshblackman50% (2)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- 2018 12 30 OrderDocumento30 pagine2018 12 30 OrderjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- 2018 12 30 FInal JudgmentDocumento1 pagina2018 12 30 FInal JudgmentjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- US v. Texas - Interlocutory Appeal OrderDocumento117 pagineUS v. Texas - Interlocutory Appeal OrderjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 12 01 Gov ReplyDocumento41 pagine2017 12 01 Gov ReplyjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- DDC - in Re Grand Jury SubpoenaDocumento93 pagineDDC - in Re Grand Jury SubpoenajoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Order On TRO Application (P0154701x9CD21) PDFDocumento7 pagineOrder On TRO Application (P0154701x9CD21) PDFjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- District of Columbia Et Al v. Trump OpinionDocumento52 pagineDistrict of Columbia Et Al v. Trump OpinionDoug MataconisNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Grewel Et Al V Defense Distributed Et Al ComplaintDocumento101 pagineGrewel Et Al V Defense Distributed Et Al ComplaintDoug MataconisNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- 3D-Printed Guns: State of Washington Et Al. v. US Department of State, Defense Distributed Et Al.Documento52 pagine3D-Printed Guns: State of Washington Et Al. v. US Department of State, Defense Distributed Et Al.jonathan_skillingsNessuna valutazione finora

- S/ Paul S. DiamondDocumento1 paginaS/ Paul S. DiamondjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- United States District Court Western District of Washington at SeattleDocumento29 pagineUnited States District Court Western District of Washington at SeattlejoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- United States District Court For The Eastern District of PennsylvaniaDocumento18 pagineUnited States District Court For The Eastern District of PennsylvaniajoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Los Angeles LetterDocumento4 pagineLos Angeles LetterjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Supplemental Motion (7/27/18)Documento9 pagineSupplemental Motion (7/27/18)joshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- NJ Cease and Desist LetterDocumento2 pagineNJ Cease and Desist LetterjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Motion To Intervene (7/25/18)Documento61 pagineMotion To Intervene (7/25/18)joshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Defense Distributed v. State - Dismissal With PrejudiceDocumento1 paginaDefense Distributed v. State - Dismissal With PrejudicejoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Defense Distributed v. State - Emergency OrderDocumento1 paginaDefense Distributed v. State - Emergency OrderjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Washington v. Defense Distributed - Supplemental LetterDocumento10 pagineWashington v. Defense Distributed - Supplemental LetterjoshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Defense Distributed v. Department of State - Motion To Strike (7/27/18)Documento4 pagineDefense Distributed v. Department of State - Motion To Strike (7/27/18)joshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Motion For A Temporary Restraining Order (7/25/18)Documento23 pagineMotion For A Temporary Restraining Order (7/25/18)joshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Motion For A Hearing (7/25/18)Documento3 pagineMotion For A Hearing (7/25/18)joshblackman0% (1)

- Letter From The Brady Campaign (7/24/18)Documento35 pagineLetter From The Brady Campaign (7/24/18)joshblackmanNessuna valutazione finora

- PhilosophyDocumento15 paginePhilosophyArnab Kumar MukhopadhyayNessuna valutazione finora

- (Journal For The Study of The Old Testament. Supplement Series - 98) Younger, K. Lawson-Ancient Conquest Accounts - A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing-JSOT Press (1990)Documento393 pagine(Journal For The Study of The Old Testament. Supplement Series - 98) Younger, K. Lawson-Ancient Conquest Accounts - A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing-JSOT Press (1990)Andrés Miguel Blumenbach100% (3)

- SCDL Project GuidelinessDocumento12 pagineSCDL Project GuidelinessveereshkoutalNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 3 SolutionsDocumento7 pagineAssignment 3 SolutionsFernando ClaudioNessuna valutazione finora

- Vastu For House - Home Vastu Test - Vastu Shastra Score For House - Vastu House Facing - Vastu Shastra Home PDFDocumento3 pagineVastu For House - Home Vastu Test - Vastu Shastra Score For House - Vastu House Facing - Vastu Shastra Home PDFSelvaraj VillyNessuna valutazione finora

- Immigrant Women and Domestic Violence Common Experiences in Different CountriesDocumento24 pagineImmigrant Women and Domestic Violence Common Experiences in Different Countriesapi-283710903100% (1)

- Letterhead of OrganizationDocumento3 pagineLetterhead of OrganizationeyoNessuna valutazione finora

- Group5 Affective Social Experiences PrintDocumento11 pagineGroup5 Affective Social Experiences PrintshrutiNessuna valutazione finora

- Innovativeness and Capacity To Innovate in A Complexity of Firm-Level Relationships A Response To WoodsideDocumento3 pagineInnovativeness and Capacity To Innovate in A Complexity of Firm-Level Relationships A Response To Woodsideapi-3851548Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 3 The Filipino WayDocumento12 pagineChapter 3 The Filipino WayJoy Estela MangayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- 50 Activities For Achieving Excellent Customer ServiceDocumento272 pagine50 Activities For Achieving Excellent Customer ServiceTrinimafia100% (1)

- Self Concept and Self EsteemDocumento5 pagineSelf Concept and Self EsteemNurul DiyanahNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 Hermetic PrinciplesDocumento2 pagine7 Hermetic PrinciplesFabrizio Bertuzzi100% (2)

- Bogner Et Al-1999-British Journal of ManagementDocumento16 pagineBogner Et Al-1999-British Journal of ManagementItiel MoraesNessuna valutazione finora

- A Tribute To Frank Lloyd WrightDocumento3 pagineA Tribute To Frank Lloyd WrightJuan C. OrtizNessuna valutazione finora

- EnglishElective SQPDocumento11 pagineEnglishElective SQPmansoorbariNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax TSN Compilation Complete Team DonalvoDocumento46 pagineTax TSN Compilation Complete Team DonalvoEliza Den Devilleres100% (1)

- Contoh Proposal The Implementation KTSP PDFDocumento105 pagineContoh Proposal The Implementation KTSP PDFdefryNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Have A Great Marriage - Bo SanchezDocumento23 pagineHow To Have A Great Marriage - Bo SanchezLady Marquez100% (12)

- Reading Comprehension Exercise # 211Documento2 pagineReading Comprehension Exercise # 211Nuria CabreraNessuna valutazione finora

- Ulrich 1984Documento12 pagineUlrich 1984Revah IbrahimNessuna valutazione finora

- Ken Done Lesson 2Documento4 pagineKen Done Lesson 2api-364966158Nessuna valutazione finora

- Scion - AyllusDocumento30 pagineScion - AyllusLivio Quintilio GlobuloNessuna valutazione finora

- Trigonometry FunctionsDocumento14 pagineTrigonometry FunctionsKeri-ann Millar50% (2)

- Mathematics Quiz 1 Prelims Kuya MeccsDocumento13 pagineMathematics Quiz 1 Prelims Kuya MeccsBeng BebangNessuna valutazione finora

- Persian 3 Minute Kobo AudiobookDocumento194 paginePersian 3 Minute Kobo AudiobookslojnotakNessuna valutazione finora

- Towards AnarchismDocumento4 pagineTowards AnarchismsohebbasharatNessuna valutazione finora

- Pi Ai LokåcåryaDocumento88 paginePi Ai Lokåcåryaraj100% (1)

- 12: Consumer BehaviourDocumento43 pagine12: Consumer Behaviournageswara_mutyalaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Characteristics of NewsDocumento1 paginaThe Characteristics of NewsMerrian SibolinaoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great MigrationDa EverandThe Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great MigrationValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (1568)

- You Sound Like a White Girl: The Case for Rejecting AssimilationDa EverandYou Sound Like a White Girl: The Case for Rejecting AssimilationNessuna valutazione finora

- Reborn in the USA: An Englishman's Love Letter to His Chosen HomeDa EverandReborn in the USA: An Englishman's Love Letter to His Chosen HomeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (17)

- The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics and the Law That Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of AmericaDa EverandThe Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics and the Law That Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (43)

- They Came for Freedom: The Forgotten, Epic Adventure of the PilgrimsDa EverandThey Came for Freedom: The Forgotten, Epic Adventure of the PilgrimsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (11)

- City of Dreams: The 400-Year Epic History of Immigrant New YorkDa EverandCity of Dreams: The 400-Year Epic History of Immigrant New YorkValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (23)