Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Aclpaperrevsubmitted

Caricato da

Catalin Adrian IovaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Aclpaperrevsubmitted

Caricato da

Catalin Adrian IovaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Do Liberal Market Lconomies' Really Innovate More

Radically than Coordinated Market Lconomies'?

Hall & Soskice Reconsidered

Dirk Akkermans

*

, Carolina Castaldi

**

and Bart Los

***,4

Uniersity o Groningen, laculty o Lconomics and Business, P.O. Box 800, 900 AV Groningen, 1he

Netherlands,

e-mail: d.h.m.akkermansrug.nl

Utrecht Uniersity, Department o Innoation Studies, and Groningen Growth and Deelopment Centre, P.O.

Box 80115, 3508 1C Utrecht, 1he Netherlands,

e-mail: c.castaldigeo.uu.nl

Uniersity o Groningen, laculty o Lconomics and Business, and Groningen Growth and Deelopment Centre,

P.O. Box 800, 900 AV Groningen, 1he Netherlands,

e-mail: b.losrug.nl

4

Corresponding author. Phone: -31 50 36331. lax: -31 50 363 33

ABS1RAC1

In 1arietie. of Caitati.v; 1be v.titvtiovat ovvaatiov. of Covaratire .aravtage, Peter lall and Daid

Soskice argue that technological specialization patterns are largely determined by the preailing

ariety o capitalism`. 1hey hypothesize that liberal market economies` specialize in radical

innoation, while coordinated market economies` ocus more on incremental innoation. Mark

Zachary 1aylor ,2004, conincingly argued that lall and Soskice`s empirical test is undamentally

lawed and proposed a more appropriate test o their conjecture. le rejected the arieties o

capitalism explanation o innoation patterns. \e extend and reine 1aylor`s analysis, using a

broader set o radicality indicators and making industry-leel comparisons. Our results indicate

that lall and Soskice`s conjecture cannot be upheld as a general rule, but that it suries closer

scrutiny or a substantial number o industries and an important dimension o radicality.

Keywords: arieties o capitalism, technological specialization, patent citations.

1

Do Liberal Market Lconomies' Really Innovate More

Radically than Coordinated Market Lconomies'?

Hall & Soskice Reconsidered

J. Introduction

In the extensie introduction to their inluential edited olume, Peter A. lall and Daid Soskice

,l&S, argue that the technological specialization patterns o deeloped countries are largely

determined by the arieties o capitalism` preailing in these countries ,lall & Soskice, 2001,.

1

In liberal market economies` ,LMLs,, the actiities o economic actors are mainly coordinated

through market institutions, in an enironment characterized by competition and ormal

contracting. In coordinated market economies` ,CMLs,, howeer, strategic interaction between

irms and other actors play a much more important role in determining the rate and direction o

economic actiities. 1ypical examples o LMLs are the US and the UK. 1he group o CMLs

contains Germany and Japan, among others.

2

l&S hypothesize that LMLs would specialize in radical innoation, while CMLs would ocus

more on incremental innoation. \e beliee that l&S`s empirical test o this hypothesis is

undamentally lawed. In a recent article, 1aylor ,2004, criticized l&S`s testing procedure as well.

lis alternatie testing procedure led him to reject the arieties o capitalism explanation o

specialization patterns. 1he testing procedure we propose in this paper diers rom 1aylor`s in

two main respects: it studies ,de,specialization in radical innoations at a more disaggregated leel

,industries instead o aggregate economies, and it considers a more general set o radicality

indicators.

1o understand why we join 1aylor ,2004, in thinking that l&S`s empirical analysis yields

unwarranted claims, we should irst explain their testing procedure. 1hey compared the

innoation specialization patterns o two countries: the US ,an LML, and Germany ,a CML,.

Data rom the Luropean Patent Oice on patents granted in 1983-1984 and 1993-1994 were

used to inestigate in which technology classes these countries patented relatiely heaily. 1heir

results indicate that the US patented relatiely heaily in technology classes related to

biotechnology, telecommunications and semiconductors. 1hese are, according to l&S,

technologies characterized by radical innoations. Germany, on the other hand, obtained

relatiely many patents in technology classes such as transport and mechanical engineering, which

1

By now, hundreds o contributions to social sciences were inspired by l&S. Lxamples o subields inluenced by

l&S are political science ,e.g., Kenworthy, 2005, and Kitson, 2005,, human resource management ,e.g. Aguilera

& Dencker, 2004,, industrial relations ,e.g., lancke & Rhodes, 2005,, goernance studies ,e.g., Griiths &

Zammuto, 2005, and innoation studies ,e.g., Casper & Kettler, 2001, and Asheim & Coenen, 2006,.

2

l&S also identiy an intermediate` group, o which lrance and Italy are important members ,lall & Soskice.

2001, p. 21,. Below, we will present l&S`s ull categorization o countries.

2

would eature more incremental innoations. 1hese results are considered to conirm the l&S

hypothesis.

1he approach o l&S can be criticized on many grounds, but we will ocus on three.

3

lirst, it

is highly questionable to contend that a comparison o two countries yields eidence that

supports a hypothesis about much larger groups o countries.

4

Second, we agree that a

technology class like semiconductors is much more susceptible to radical innoation than a class

like transport, but would not be surprised i the ew radical innoations in transport would cluster

in a speciic country. 1he eidence that innoations ,irrespectie o their radical or incremental

nature, within a technology class tend to cluster in speciic geographical locations is abundant.

5

1here is no reason to a riori discard the contention that this localization can also be obsered or

radical innoations only, too. 1hird, scholars o technological change proided ample eidence o

the existence o technology lie cycles.

6

Radical innoations occur relatiely oten during the early

stages o the lie cycle o a technology, while incremental innoations are much more common in

later stages. lence, l&S`s choice to denote speciic technologies as characterized by radical

innoations and others as characterized by incremental innoation is not without problems, i

only because l&S adopt identical classiications or their 1983-1984 and 1993-1994 analyses.

Some o the technologies with a strong emphasis on radical innoations in the early period might

well hae entered a stage in the technology liecycle dominated by incremental innoations later

on.

\e propose a test that does not suer rom the problems sketched aboe, using data

originating rom the US Patent Oice and obtained rom the NBLR Patent-Citations Data lile.

Ater haing used a concordance to map patent classes to industry classes, we will construct

industry-speciic requency distributions or seeral measures o basicness ,or radicality`,

computed rom patent citation data or the period 195-1995. In doing so, we draw on preious

work by 1rajtenberg et at. ,199, who built on the basic idea that patented innoations that are

oten cited in subsequently issued patents are relatiely more important.

Next, the requency

distributions will be compared with similar requency distributions constructed rom patents

3

A more extensie list o problems pertaining to l&S`s empirical approach can be ound in Akkermans ,2005,.

4

Some o l&S`s results run counter to earlier work based on patent statistics or a much broader set o countries

that ocused on other aspects than LML s. CML dierences, such as dierences in country size ,Archibugi &

Pianta, 1992,.

5

See, or instance, Canils ,2000, Chapter 8, and Breschi ,2000,. 1he presence o uniersities generating spilloers

concerning rontier technologies ,see, e.g. Audretsch & leldman, 1996, and Piergioanni & Santarelli, 2001, is

likely to play an important role in this clustering.

6

Utterback & Abernathy ,195, is the seminal contribution in this respect. Klepper ,1996, proided a ormal

model explaining obsered regularities.

1rajtenberg ,1990, is generally seen as the genesis o this type o research, which ocused solely on American

issues or a long time. Maurseth & Verspagen ,2002, is an example o a recent contribution addressing citation

patterns across Luropean regions. See Michel & Bettels ,2001, or an account o dierences in citation practices

across international patent oices.

3

granted to seeral LMLs and CMLs, to see whether LMLs really specialize in radical innoations

or not. 1he non-parametric statistical testing procedures will also allow us to ind out whether

such a inding ,i any, holds or all industries, or or a limited subset o industries only. Our

analysis adds to 1aylor ,2004,, whose study reuted the l&S hypothesis, in two ways. lirst, we

argue that the analysis should explicitly take dierences across industries into account, so the

appropriate leel o analysis is the industry rather than the aggregate economy leel.

8

Second, we

consider a broader set o radicality indicators than 1aylor, whose analysis ocused on the number

o citations receied. Our alternatie indicators consider the range o technologies aected by the

patented innoation as well as the range o technologies rom which knowledge was used to

arrie at the patented innoation. As will be shown below, this leads to a nuanced picture: 1aylor

is right in burying the l&S hypothesis as a general law, but or a number o industries and

dimensions o radicality the l&S hypothesis appears to be correct.

1he organization o the paper is as ollows. In Section 2, we briely discuss the broad

background o the l&S distinction between LMLs and CMLs and l&S`s results on the

preailing types o innoation in these countries. Section 3 introduces the testing procedures

adocated by us, as well as a detailed description o the ariables that play a role in these tests.

Section 4 is deoted to a discussion o the data. 1he actual tests o the l&S hypothesis are

reported upon in Section 5. Section 6 concludes.

2. Innovation in Liberal and Coordinated Market Lconomies

1he l&S hypothesis reoles around two conceptualizations that should be discussed more

extensiely. lirst, the most important dierences between liberal market economies ,LMLs, and

coordinated market economies should be dealt with. Second, we should summarize how l&S

look at the distinction between radical and incremental innoation. 1his section discusses these

issues, describes the methodologies applied by l&S and inally interprets their main results.

1he Varieties o Capitalism` approach adocated by l&S stresses the notion that the way

irms resole many o the coordination problems they are conronted with aries across

countries.

9

LMLs and CMLs can be seen as two archetypes representing the extremes o a

continuum. In LMLs,

8

1aylor ,2004, added intercept dummies or six broad technology classes to its equations regressing the radicality

o patents ,measured by the number o citations receied, on the ariety o capitalism they originated rom. 1his

approach assumes that the sensitiity o the radicality o innoations to originating rom either an LML or a

CML is equal across technology classes.

9

In an earlier book ,Albert, 1993,, Michel Albert also distinguished between types o capitalism, arguing that social

coalitions and politically constructed institutions produce goernment policies and that institutional arrangements

shape the eects o goernment policy.

4

.firv. cooraivate tbeir actiritie. rivarit, ria bierarcbie. ava covetitire var/et arravgevevt.. ;.)

Mar/et retatiov.bi. are cbaracteriea b, tbe arv`.tevgtb ecbavge of gooa. or .errice. iv a covtet of covetitiov

ava forvat covtractivg. v re.ov.e to tbe rice .igvat. geveratea b, .vcb var/et., tbe actor. aa;v.t tbeir

rittivgve.. to .vt, ava aevava gooa. or .errice. ;.). ,lall & Soskice, 2001, p. 8,

In CMLs, on the other hand,

. firv. aeeva vore bearit, ov vovvar/et retatiov.bi. to cooraivate tbeir evaearor. ritb otber actor. ava

to cov.trvct tbeir core covetevcie.. 1be.e vovvar/et voae. of cooraivatiov geveratt, evtait vore etev.ire

retatiovat or ivcovtete covtractivg, vetror/ vovitorivg ba.ea ov tbe ecbavge of rirate ivforvatiov iv.iae

vetror/., ava vore retiavce ov cottaboratire, a. oo.ea to covetitire, retatiov.bi. to bvita tbe covetevcie. of

tbe firv. ;.) tbe eqvitibria ov rbicb firv. cooraivate iv cooraivatea var/et ecovovie. are vore oftev tbe re.vtt of

.trategic ivteractiov avovg firv. ava otber actor.. ,lall & Soskice, 2001, p. 8,

1o operationalize the distinction between LMLs and CMLs or analytical purposes, l&S

proposed two indicators o institutional practices. 1hese relate to corporate inance and labor

markets. ligh leels o stock market capitalization ,deined as the ratio o the market alue o

listed companies to GDP, and low leels o employment protection ,measured by a composite

index o the ease o hiring and iring`, relect reliance on markets. Inormal cluster analysis leads

l&S to a classiication o 23 OLCD countries. Six countries were denoted as LMLs and eleen

countries as CMLs. 1he six members o the third group, which we will denote as MMLs ,mixed

market economies`,, are sometimes reerred to as the countries representing the Mediterranean`

ariety o capitalism.

10

l&S ,pp.20-21, show that LMLs and CMLs do not dier too much in terms o their

economic perormance. 1he leels o GDP per capita and the growth rates o GDP are in the

same order o magnitude. Unemployment rates, though, are generally higher in LMLs. In general,

the distribution o income is much more unequal in LMLs and aerage working hours are longer.

Unortunately, the l&S hypothesis concerning the nature o innoation in the two arieties was

tested using data or two countries only, as we will explain below.

l&S ,pp. 36-41, deelop sensible arguments why LMLs should be relatiely good at

deeloping radical innoations. loweer, they neither gie a clear deinition o radical

innoations, nor o incremental innoation. 1hey indicate that radical innoationevtait. .vb.tavtiat

.bift. iv roavct tive., tbe aeretovevt of evtiret, ver gooa., or va;or cbavge. to tbe roavctiov roce..e. ;.)

,lall & Soskice, 2001, pp. 38-39,, whereas incremental innoation is var/ea b, covtivvov. bvt

10

1he Mediterranean` ariety o capitalism eatures strong reliance on non-market mechanisms in corporate

inance and a ocus on market mechanisms in labor relations. 1he classiication o countries can be ound in

1able 2 below. In line with l&S, we excluded CML Iceland rom the statistical analysis, as a consequence o

which it does not appear in the table.

5

.vatt.cate ivrorevevt. to ei.tivg roavct tive. ava roavctiov roce..e. ,lall & Soskice, 2001, p.39,.

Although most economists o innoation will agree that these descriptions do at least relect the

most important aspects o widely accepted deinitions o the two archetypes o innoation, only

ew will support the operationalization o these descriptions chosen by l&S.

l&S stated that radical innoation is particularly important or dynamic technology ields,

such as biotechnology, semiconductors, sotware, and telecommunications equipment. 1hey

associated incremental innoation with technology ields like machine tools, consumer durables,

engines and specialized transport equipment. 1o test their hypothesis, l&S compared the

technological specialization patterns o a typical LML ,the United States, and a typical CML

,Germany,. 1hey ound that the Luropean Patent Oice granted relatiely many patents in

dynamic technology ields to US inentors, and relatiely many patents in technology ields

associated to incremental innoations to German inentors. 1hese indings were presented as

eidence in aor o l&S`s central hypothesis.

One o the widely accepted acts about innoations is that their impacts are characterized by

skewness. Len in technologically dynamic sectors, many innoations do not aect the

proitability and,or stock market aluation o irms ,see Scherer et at., 2000,. An indication that

many innoations do not hae an impact in a technological sense was proided by 1rajtenberg

,1990,. le showed that almost hal o all patents eer granted up to 1982 in the once

technologically dynamic ield o computed tomography ,C1, scanners were neer cited in

subsequent patents. As will be discussed below, this is a strong sign that such patents were not

radical at all, een though they belong to a ield that would most probably hae been associated

to radical innoation by l&S.

1he Neo-Schumpeterian,eolutionary theory on innoation also stresses that technologies

cannot be associated with radical innoations alone. Dosi ,1982,, or example, argues that

technologies, like science, are sometimes subject to paradigm shits. 1hese shits are characterized

by the emergence and diusion o one or a ew radical innoations. Aterwards, bunches o

minor innoations take place along the lines o the new technological trajectory. 1ogether, these

might yield substantial gains in terms o productiity, but they are o an incremental nature.

Similar arguments can be ound in Utterback & Abernathy ,195,. l&S`s claim that

specialization o LMLs in radical innoation is remarkably stable oer time ,they studied the

1983-1984 and 1993-1994 periods, is at odds with the literature, gien that they studied

technological specialization across ields rather than within ields. Although ormal inestigations

into this issue are beyond the scope o this paper, we eel that l&S`s empirical analysis tells

much more about economic specialization patterns than about technological specialization.

linally, eer since Schumpeter`s ,1942, introduction o the term creatie destruction`, radical

innoations hae had a connotation o being ery perasie, i.e. aecting technological change

and production processes in many dierent industries. 1his aspect o radicality cannot be

appropriately addressed by the type o analysis l&S opted or.

6

In this section we introduced the reader to the main hypothesis in the inluential piece by

l&S. \e do not question the arguments underlying this hypothesis. Neertheless, we are not

coninced by the empirical support or the hypothesis gien by l&S. 1his opinion was shared by

1aylor ,2004,, who also criticized l&S or their choice to test a general conjecture based on two

countries ,o which the US is oten considered to be an outlier, and or their neglect o

technology lie cycles. As ar as we are aware, the present article is the irst to address radicality in

a multidimensional way, also stressing perasieness across technologies and industries.

3. 1ests Based on Patent Citation Indicators

1his paper contributes to the relatiely recent literature that attempts to capture the importance

o innoations by means o patent citation data. In one o the pathbreaking articles in this

tradition, the basic source o inormation is succinctly described as ollows:

f a atevt i. gravtea, a vbtic aocvvevt i. createa covtaivivg etev.ire ivforvatiov abovt tbe ivrevtor, ber

evto,er, ava tbe tecbvotogicat avteceaevt. of tbe ivrevtiov, att of rbicb cav be acce..ea iv covvteriea forv.

.vovg tbi. ivforvatiov are referevce. or citatiov.. t i. tbe atevt eaviver rbo aetervive. rbat citatiov. a

atevt. vv.t ivctvae. 1be citatiov. .erre tbe tegat fvvctiov of aetivitivg tbe .coe of tbe roert, rigbt covre,ea b,

tbe atevt. 1be gravtivg of tbe atevt i. a tegat .tatevevt tbat tbe iaea evboaiea iv tbe atevt rere.evt. a voret

ava v.efvt covtribvtiov orer ava abore tbe reriov. .tate of /vorteage, a. rere.evtea b, tbe citatiov.. 1bv., iv

rivcite, a citatiov of Patevt ` b, Patevt Y veav. tbat ` rere.evt. a iece of reriov.t, ei.tivg /vorteage

vov rbicb Y bvita.. ,Jae et al., 1993, p. 580,

As was irst conirmed by 1rajtenberg ,1990,, patents that are oten cited by later patents are

more important than patents that are irtually neer cited. O course, this importance depends on

the question whether inentors were really aware o the knowledge claimed in earlier patents. An

airmatie answer to this question is not warranted, since it is not the patentee who includes

citations, but an expert employee o the patent oice. In a recent paper, howeer, Jae et at.

,2000, use results o sureys among inentors to conclude that citations do gie indications

,although noisy ones, o spilloers rom the cited inention to the citing inention.

3.a Indicators of Radicality

In this paper, we will use data contained in the NBLR Patent-Citations Data lile to distinguish

between radical and incremental innoations, like 1aylor ,2004, did. 1he general idea is that

patents that are important` according to a number o citation-based indicators are more likely to

represent radical innoations than patents that report aerage or below-aerage importance.

1hree measures o importance will be studied, number o citations receied`, measure o

generality` and measure o originality`. 1he irst measure was introduced by 1rajtenberg ,1990,,

7

the latter two by 1rajtenberg et at. ,199,. Since the database also contains records or the ariable

country o irst inentor`, we can study which countries specialize in radical patents and which

do not, or each o the dimensions o radicality.

\e will denote the indicator number o citations receied` by NCI1ING, in line with the

notation adopted by 1rajtenberg et at. ,199,. 1his indicator simply supposes that a patent that is

cited more oten than another one has had more impact on subsequent technological

deelopments and can thereore be seen as more radical.

11

As was argued in the preious section, many notions o radical innoation stress its property

o perasieness, i.e. the eature that many industries and,or technological ields are aected by

the innoation ater the innoation itsel and the knowledge associated with it hae started to

diuse ,see Lerner, 1994,. 1his aspect o importance is captured by the indicator GLNLRAL,

which was deined by 1rajtenberg et at. ,199, p. 2, as ollows:

=

i

N

k i

ik

i

1

2

NCITING

NCITING

1 GENERAL ,1,

1he second term on the right hand side is basically a lerindahl index, in which ^

i

stands or the

number o dierent patent classes ,indicated by /, rom which patent i receied citations. 1he

indicator always takes on alues between 0 and 1, and high alues represent strong

perasieness.

12

Lquation ,1, cannot be used or patents that did not receie a single citation. In

such cases we assigned a zero alue to the indicator GLNLRAL.

linally, we consider a measure that does not relate to the number or diersity o patents

citing the patent under study, but the diersity o patents it is citing itsel. I patents rom seeral

technological classes are cited in a patent, it is quite likely that many dierent types o knowledge

had to be combined` in order to come up with the patented innoation ,see, e.g., Shane, 2001, .

Such usion technologies can be seen as radical rather than incremental, because incremental

innoations generally require improements with respect to one or a ew technological ields. In

line with 1rajtenberg et at. ,199, p. 29,, we use the indicator ORIGINAL, which is also

expressed in tems o a lerindahl index:

=

i

N

k i

ik

i

1

2

NCITED

NCITED

1 ORIGINAL , ,2,

11

In an early study, Albert et al. ,1991, already oered eidence that NCI1ING and experts` aluation o patented

innoations correlate positiely.

12

As is indicated in the appendix o lall et at. ,2002,, this measure o generality is biased downwards i it is based

on small numbers o citations. 1he data we use in this study hae been corrected or this bias. 1his also holds or

the originality indicator proposed below.

8

where NCI1LD

i/

represents the number o patents in technology class / cited by the patent or

which the radicality is assessed. In line with our treatment regarding the GLNLRAL indicator o

patents receiing no citations, we assign a zero alue to the ORIGINAL indicator i a patent does

not contain any reerence to earlier patents.

3.b Construction of Radicality Quantiles

\e will deine radical innoations using rankings o patents based on the three indicators

discussed aboe. Patents that hae a high score as compared to other patents will be considered

as radical ones. At least two important caeats apply, howeer.

lirst, propensities to patent innoations ary strongly across industries, which consequently

has implications or receied citations ,especially rom subsequent patents granted to irms in the

same industry,. Using a Luropean dataset, Verspagen & De Loo ,1999, ounnd aerage receied

citations-to-patents ratios ranging rom 0.39 in the shipbuilding industry to 1.16 in the computer

manuacturing industry. lall et at. ,2002, presented qualitatiely similar results or American

patents. Substantial parts o these dierences seem to be due to arying industry-speciic abilities

o patents to act as ,i, a way to preent competitors rom outright imitation, ,ii, a way to orce

other irms into negotiations ,oten about cross-licensing, or ,iii, a way to hae potential

competitors changing their technological strategies, by encing` or blocking` ,see Cohen et at.,

2000,.

Second, not all citations are receied at once. Verspagen & De Loo ,1999, reported that the

,skewed, distribution o citations to patents issued by the Luropean Patent Oice applied or

between 199 and 199 had a mean lag o 4.6 years. Based on citations to USP1O patents

issued during a much longer period, lall et at. ,2002, een ound mean lags o up to 16 years.

1he consequence o the oten long lags is that relatiely new patents will oten hae receied

ewer citations ,and,or citations in ewer technological ields, than older patents. Another issue

that precludes reasonable comparisons o citation-based indicators across years relates to

obsered increasing propensities to cite. As lall et at. ,2002, argued, increased computerization o

the patent system led to less time-consuming queries by patent examiners, as a consequence o

which the citations to patent ratios rose considerably in the 1980s.

1o deal with these dierences, we base our rankings on industry-speciic cohorts o patents

applied or in a gien year. 1hat is, we irst construct quantiles or patents associated with

industry i applied or in year t. Now, we can deine the patents in the 10th decile as radical

innoations.

13

\e represent the number o these patents granted to inentors in country / by

13

O course, it is rather arbitrary to deine the bottom 90 percent o innoations as incremental and the top 10

percent as radical. Below, we will also report some analyses based on a 95,5 percent diision. \e will also use

analytical techniques that take the whole set o quantiles into account, without an explicit borderline between

incremental and radical innoations. In uture work, it might be interesting to use analytical techniques that study

distributional characteristics to discern radical innoations rom incremental innoations. 1echniques explored by

9

k

it

n

*

. Next, useul aggregations can be obtained by summing oer appropriate indexes. 1he

number o important innoations produced by country / in year t, or example, can be deined as

m

i

k

it

k

t

n n

1

* *

,with v standing or the number o industries,, and the number o important

innoations produced by industry i in country / oer the entire period can be written as

T

t

k

it

k

i

n n

1

* *

,with 1 representing the number o years,. lor some analytical techniques described

below, requencies o incremental innoations are also required. 1he notation will be equialent,

but asterisks will be resered or radical innoations. 1he number o patents related to

incremental innoations granted to inentors in country / will thus be indicated by by

k

it

n .

3.c Analytical 1echniques

\e will basically use three techniques to analyze the question whether LMLs do indeed specialize

in radical innoations, as was contended by l&S. 1he irst two techniques mainly sere

descriptie goals, the third one enables us to produce a statistically sound erdict. lirst, we will

present Reealed Comparatie 1echnological Adantages` ,RC1As,, which are deined in the

same ein as Reealed Comparatie Adantages used in empirical analyses o trade patterns. lor

industry i, country /`s RC1A is deined as

( )

( )

= =

+

+

=

C

k

k

i

k

i

C

k

k

i

k

i

k

i

k

i k

i

n n n

n n n

1

*

1

*

* *

RCTA ,3,

RC1As can also be computed or speciic time periods or or aggregate economies ,and een

groups o economies such as the class o CMLs, by choosing appropriate summations. RC1As

deined as in equation ,3, always yield nonnegatie alues. Values smaller than 1 indicate

negatie specialization` in the generation o important patents, alues greater than 1 point to

specialization. A problem with this conentional way o presenting degrees o specialization is

that negatie specializations are compressed into the |0,1 interal, while positie specialization

are spread oer 1,~. 1o report degrees o specialization in a symmetric ashion, we will always

present the natural logarithms o the RC1As. 1his type o analysis is ery comparable to what

l&S used as their inormal test. 1he undamental dierence between their reliance on patents by

industry to deine radical innoations and our reliance on citation indicators remains, howeer.

1he central l&S hypothesis suggests higher alues o the logs o the RC1As or LMLs than or

CMLs.

Our second technique to depict positie or negatie specialization does not rely on a single

boundary between incremental and radical innoations. \e will present histograms in which the

Silerberg & Verspagen ,200, oer a good point o departure ,see Castaldi & Los, 2008, or some industry-leel

explorations,.

10

quantiles o radicality are depicted on the horizontal axis. 1he height o the bars indicate the

relatie requencies o patents belonging to these quantiles as granted to inentors in the country

or group o countries o interest. I the country would show no specialization in innoations o a

speciic importance decile, all bars would be equally high ,i.e. 0.10,. In this case, the 10 least

important patents issued by USP1O to any inentor in the world would account or exactly 10

o the total number o patents awarded to this country. I the l&S hypothesis is true, LMLs

would yield patterns with a more positiely or less negatiely sloping set o bar heights,

depending on the specialization o countries that got patents granted but are not included in the

analysis.

1he RC1As and diagrams with relatie requencies can sketch insightul pictures, but do not

proide us with opportunities to test whether obsered dierences between LMLs and CMLs are

statistically signiicant. In that respect, we would not gain anything in comparison to l&S. 1o

test or dierences in the innoation specialization o two countries or groups o countries, we

could use a standard _

2

test based on contingency tables. Such a test compares the actually

obsered requencies or all cells o the table ,i.e. requencies o patents included in the deined

quantiles or the respectie countries, with the expected requencies under the null hypothesis o

no dierences in specialization. As is well known rom the literature on categorical data analysis

,see, e.g. Agresti, 2002, this test is only appropriate i none o the two dimensions o the table can

be ordered in any reasonable way. In our case, howeer, the quantiles represent categories that

can be measured on an ordinal scale: the tenth decile is closer to the ninth decile than to the

third. 1he statistical test we use to aoid this problem was originally proposed by Bhapkar ,1968,.

It is also based on obsered and expected requencies in contingency tables. An example o such

a table is gien in 1able 1.

Insert 1able J about here

It is assumed that country A got granted twice as many patents as country B. I we denote the

unknown probability that a random obseration rom the ;th sample ,;~country A, country B,

belongs to the ith category ,i~1, ., 10, by :

i;

, we might ormulate our null hypothesis as l

0

:

i

ij i

a is independent o ;. In this expression is a

i

the score` assigned to category i.

14

l

0

thus

implies that the mean scores are identical or the two countries or groups o countries.

1he Bhapkar ,1968, test inoles the computation o a test statistic that should be compared

with a critical alue rom a _

2

distribution with 1 degree o reedom ,i two countries are

compared, in the general case the number o degrees o reedom is equal to the number o

samples minus one,. Let

i;

~v

i;

,^

;

, that is, the obsered requencies diided by the row totals.

14

1he choice o scores is somewhat arbitrary. In the bottom row o 1able 1, equidistant scores hae been

indicated. In the analysis below, we will experiment with an alternatie score setup, that stresses the importance

o obserations in higher deciles to a substantial extent.

11

Now, the sample analogs o the population means are

=

i

ij i j

p a A . I we write r

;

~^

;

,

;

, with

( )

=

i

ij j i j

p A a B

2

, Bhapkar ,1968, p.331, shows that the generalized least square technique

now yields a large sample test statistic w C A w X

j

j j

2 2

=

, with

=

j

j j

A w C and

=

j

j

w w . I the null hypothesis o a common mean cannot be rejected, the corresponding

estimate or this mean equals C,r.

15

4. Data Issues

As mentioned aboe, our main source o data is the NBLR Patent-Citations Data lile, which

contains data on patent citations in the period 195-1999 to all utility patents granted by the US

Patent Oice in the period 1963-1999. lor the present analysis, we used the large subset o these

patents applied or in the somewhat shorter period 190-1995, to aoid possible problems

concerning citation lags ,see section 3.b,. 1he dataset contains nearly 2.1 millions o patents, o

which nearly 0.9 millions were granted to inentors outside the US. 1hese patents also include

patents granted to indiiduals and goernments, but more than 5 were awarded to non-

goernmental organizations ,corporations and uniersities,.

16

1he radicality indicators as taken rom the same source are based on citations included in

patents granted rom 195 and 1999. lall et at. ,2002, report that more than 16.5 millions o

citations were inoled in the underlying computations. Sel-citations ,i.e., citations to preious

patents granted to the same organization, are included. 1he GLNLRAL and ORIGINAL

indicators o radicality were constructed on the basis o citations rom and to patents classiied

into 426 3-digit original patent classes. As we will see below, this classiication is much more ine-

grained than the 42-industry classiication we use to study specialization patterns. 1his implies

that it is ery well possible that ery general innoations did hae technological consequences in

one or only a ew industries as deined below. \e do not consider this as a problem, because

patents with a high GLNLRAL indicator will hae had a more widespread impact within such an

industry than a patent with a low alue or GLNLRAL. As such, the ormer patent can still be

considered as more radical than the latter.

\e assign patents to industries by means o O1Al classiication codes contained in US

patents. 1hese codes are not contained in the NBLR Patent-Citations Dataile, but we could

easily match the industry codes in USP1O`s PA1SIC-CONAML database to the citation data.

1he O1Al classiication assigns patents to one or more industries that are most likely to use the

patented process or to manuacture the patented inention. 1o this end, a concordance was set

15

1he hypothetical samples rom country A and country B would yield an `-statistic o 656., which is well aboe

the 5 critical alue o 3.84 taken rom the _

2

distribution with 1 d... 1hus, the assumption that the patents o

country A and country B hae an equal mean radicality should be rejected.

16

See lall et at. ,2002, p. 413, or details.

12

up that maps 124,000 USPC classes onto 41 ields, plus one other industries` category. 1hus, at

the most detailed leel, 42 industries are discerned.

1

1his is also the classiication we use or the

purpose o this paper. 1he ull classiication can be ound in the Appendix..

An issue we had to deal with is that 30 o the patents examined by USP1O were assigned

to multiple SIC codes. Actually, some patents got as many as seen codes. In studies like these,

two approaches can be adopted. I the whole counts` approach is chosen, the patent count or

all SICs concerned is increased by one. 1his approach emphasizes the nonrial nature o

knowledge, in the sense that the useulness o a patent or a gien industry is not necessarily

reduced i other industries could also beneit rom it. A drawback is that i one would like to

aggregate patent counts oer industries, one ends up with more patents than hae been granted

to inentors in that country. 1his disadantage is aoided by the second approach, ractional

counting`. 1his approach amounts to adding 1, to patent counts o SICs assigned to the patent.

1his implies that the patent is shared`. \e opted or the ractional counting method, because

we would encounter problems in assigning patents to radicality quantiles i a patent would all in

the th quantile or one industry and in the ,th quantile or another releant one. Results or

aggregate economies would be lawed, because either the recorded number o patents would be

higher than the actual number, or the deciles would not be represented equally in the population

o all patents granted by USP1O.

18

S. Lmpirical Results

S.a Revealed Comparative 1echnological Advantages

As a irst indication or the empirical alidity o the l&S hypothesis, we consider the logarithms

o the Reealed Comparatie 1echnological Adantages ,RC1As, gien by equation ,3,. \e

present two sets o results or each o the three radicality indicators. In 1able 2, the columns in

the let panel gie specialization patterns or the case in which radical innoations are deined as

belonging to the 10th deciles. 1he three columns in the right panel are computed or a stricter

deinition o radical innoation. Only those patented innoations that are among the top 5 o

patents iled in a year or an industry in terms o importance are considered to be radical.

In general, the results are quite robust or the choice o upper quantiles deining radicality.

Countries that are specialized in radical innoation in the let panel show a similar specialization

in the right panel. Quite oten, the specialization patterns are somewhat more pronounced i

radical innoations are deined in a stricter sense. 1he results are also robust or the indicator o

1

See lirabayashi ,2003, or an oeriew o issues related to the principles underlying the PA1SIC database.

Griliches ,1990, p. 166, was quite critical about early ersions o the O1Al classiication, but improements

hae been sizeable.

18

1he latter problem would occur i we would decide to assign the patent to the highest decile ound across the

industries to which it is assigned by the PA1SIC data.

13

radicality chosen. Most countries appear to hae experienced a negatie specialization in radical

innoation or NCI1ING, GLNLRAL and ORIGINAL. 1he only two countries or which the

direction o specialization is dependent on the indicator are Ireland and Portugal. lor the latter

country, this result might be a statistical arteact, due to the ery small number o patents granted

to inentors residing in this country.

Insert 1able 2 about here

Besides the United States, Ireland is also the only country or which some indication o a

specialization in radical innoation is ound. lor the set o LMLs, we ind specialization in

incremental innoations. It should be stressed, howeer, that we excluded the US rom the LML

category, unlike l&S. \e did this or two reasons. lirst, the decision to apply or a patent is

likely to dier between the home market and oreign markets ,see Jung & Imm, 2002,. It could

well be that inentors decide irst to patent at the domestic patent oice to get acknowledged as

being a technically capable inentor`. Applications or oreign patents are more oten done ater

an ealuation o the potential commercial alue o such a patent. lence, domestic patents are

oten thought to be o an inerior quality, on aerage. Second, we eel that the alidity o l&S`s

hypothesis should not hinge on one country ,see also 1aylor, 2004,. 1he United States are oten

considered to be the world`s technological leader. 1his might o course be due to their early

LML-character, but it appears sensible to us to consider the US as a special case.

19

Beore looking at the three arieties o capitalist economies as discerned by l&S, it is useul

to assess the eects o the US on the results. 1his country shows a specialization in radical

innoation, which runs counter to the Jung & Imm argument discussed aboe. Gien the large

raction o all patents granted by USP1O to inentors in the US ,see the irst column o 1able 3,,

it is to be expected that most other countries will appear to be specialized in incremental

innoation. 1his appears to hold or the group o LMLs as well. 1he negatie alues are closer to

zero, howeer, than the RC1As ound or the group o CMLs. 1his can be seen as proisional

eidence in aor o l&S. 1he mixed type o capitalist economies appears to be most strongly

specialized in incremental innoation.

Inspection o the RC1As or indiidual countries leads us to conclude that the specialization

patterns ary quite a bit across countries belonging to a gien type o economy. In line with

1aylor ,2004,, we ind that New Zealand and, to a lesser extent, Australia are outliers among the

LMLs. 1hese countries turn out to hae a specialization pattern that is closer to that o a typical

CML. 1he opposite holds or CML Japan. It might be that this is due to an argument put

orward by Archibugi & Pianta ,1992,, who contended that large economies tend to be less

specialized in speciic technology ields than small countries, because the latter do not hae the

19

One could also inoke their unequalled goernment-sponsored deence-related technological actiities as an

argument to consider the US as a non-representatie LML.

14

resources to diersiy their actiities to the same extent. \e eel, though, that this argument is

much weaker in the present context. A small country with a strong specialization in

communication technology, or example, would not waste resources by pursuing radical and

incremental innoations simultaneously.

20

1he heterogeneity within arieties o capitalism is a

irst indication against the l&S hypothesis, which suggests homogeneous LMLs s.

homogeneous CMLS.

Beore turning to results or methods that iew the radical s. incremental innoation

distinction not as a binary issue but as a matter o gradual dierences, we would like to stress that

the RC1As presented in 1able 3 are computed or aggregate economies. Similar indicators can

also be calculated at the industry leel. lor reasons o breity, we will not document all results

here, but restrict the exposition to a ew selected industries ,that can be seen as coering

substantial parts o the manuacturing sector,, the top 10 deinition and the NCI1ING

indicator only. 1he results are documented in 1able 3.

Insert 1able 3 about here

Although we will postpone ormal statistical analysis concerning dierences among populations

based on samples until subsection 5.c, we can iner rom 1able 3 that LMLs other than the US

do not systematically show RC1As that indicate a stronger specialization in radical innoation. In

our o the eight selected industries, CMLs tend to be more directed towards generating radical

innoations.

S.b Histograms for Radicality Distributions

1o describe more general technological specialization patterns, we present three histograms. 1he

relatie requencies o patents belonging to deciles o the entire population o all patents granted

by USP1O deined using the NCI1ING indicator are depicted in ligure 1.

Insert Iigure J about here

1he our ,groups o, economies exhibit clear specialization patterns, in the sense that the heights

o the bars are either monotonically increasing or decreasing. 1he specialization in more radical

innoations by the US already apparent rom 1able 2 is strongly conirmed by the graph. 1he US

are not only oerrepresented` in the top 10 and top 5 patents, but also in less outspoken

important innoations. 1he opposite holds or economies o the Mediterranean ariety o

capitalism. ligure 1 indicates that the LMLs ,excluding the US, and the CMLs considered as

groups hae rather similar specialization patterns. LMLs did obtain relatiely many ery

20

An eect o size is clearly present or Portugal. 1his country did not produce a single patent that belonged to the

5 most important USP1O patents in terms o generality. Consequently, its specialization in such innoations

appears to be minus ininity.

15

unimportant patents, but also many ery important patents. In the intermediate deciles, CMLs

are relatiely strongly represented. Although isual inspection indicates some dierences in

specialization patterns between LMLs and CMLs, we do not ind strong eidence in aor o the

l&S hypothesis.

ligures 2 and 3 present similar distributions as ligure 1, but or the GLNLRAL and

ORIGINAL indicators, respectiely.

Insert Iigure 2 about here

Insert Iigure 3 about here

1he distributions indicate that there are noticeable dierences between importance measured

according to the three proposed indicators. \ith regard to ORIGINAL, LMLs seem to be much

more specialized in radical innoation than CMLs. Concerning the GLNLRAL indicator, the

distributions or the LMLs and CMLs group is much more alike ligure 1 or NCI1ING. 1he

distributions or MMLs and the US are not sensitie in a qualitatie sense to the indicator type

chosen.

S.c Statistical tests on equality of distributions

So ar, we used descriptie statistics to study the alidity o the l&S hypothesis. In this

subsection, we turn to the results or Bhapkar`s ,1968, test outlined in Section 3. 1able 4 presents

results or pairwise comparisons o radicality distributions or the aggregates o the our groups

o countries or which the distributions were depicted in ligures 1-3. As we mentioned in our

discussion o the test, results might be sensitie to the scores assigned to each decile ,see Agresti,

2002,. 1hereore, we present results or two sets o scores. 1he let panel is obtained by using a

linear` ,or equidistant, set o scores. 1hat is, we assigned a score a

i

~i to each o the deciles. lor

the rightmost panel, we adopted a scoring system that weighs patents in the ery important

deciles more heaily. \e assigned scores a

i

~i

2

to decile i. Cells in the table contain the letters

reerring to the ,group o, countries that turned out to be the most radical o the countries

corresponding to the rows and columns, respectiely. Signiicance leels are indicated by the

number o asterisks. 1hus, C in the upper let cell indicates that CMLs were more specialized

in radical innoation than LMLs at a signiicance leel o 1, i linear scores are used and the

radicality indicator is NCI1ING.

Insert 1able 4 about here

Oerall, the results are rather robust or alternatie sets o scores. lurthermore, the dierences

are highly signiicant. 1he US turns out to be most strongly specialized in radical innoation,

irrespectie o the radicality indicator considered. MMLs are consistently ound to be least

16

specialized in radical innoation, with one major exception: i the ORIGINAL indicator is

chosen, MMLs are signiicantly more radical innoators than CMLs.

O course, the results or comparisons between LMLs and CMLs are the most interesting

rom the perspectie o this paper. In general, these results or the aggregate manuacturing

sector seem to conirm the l&S hypothesis. lor the GLNLRAL and ORIGINAL indicators,

LMLs are clearly more specialized in producing radical innoations. A dierent picture is ound

or NCI1ING, howeer. In our discussion o ligure 1, we already indicated that LMLs showed

high relatie requencies ,as compared to CMLs, or irtually non-cites and ery highly cited

patents. 1his phenomenon is relected in the test results. I ery important patents do not weight

ery heaily ,like in the set o linear scores, CMLs appear as more specialized in radical

innoations than LMLs, although signiicance is weaker than or other pairwise comparisons in

1able 4. Using scores in which ery highly-cited patents get more weight ,like in the set o

quadratic scores,, we ind that the signiicance is reduced een urther.

\e now turn to Bhapkar tests or comparisons o specialization patterns at the industry leel.

Our discussion o RC1As already indicated that results or aggregate economies ,or groups o

them, could well hide strongly heterogeneous patterns at a lower leel o aggregation. 1able 5

presents results or comparisons o specialization patterns o LMLs and CMLs or all 42

industries that we can distinguish. 1o sae space, we report results or the linear set o scores.

lor an oerwhelming majority o comparisons, application o quadratic scoring yielded

qualitatiely identical results.

1he results or ORIGINAL are ery clear. In many industries, the group o LMLs is more

specialized in radical innoation than the group o CMLs. Apparently, inentors in LMLs draw

on a much broader base o technologies in producing new innoations. I radicality o

innoations is deined in this way, strong support is ound or the l&S hypothesis. 1his result

does not carry oer to the NCI1ING and GLNLRAL indicators, howeer. lor these indicators,

the results could best be described as a mixed bag`. Generalizing the results somewhat, we ind

that LMLs are relatiely more specialized in radical innoation in industries that produce

chemicals and related products as well as in electronics industries. CMLs, howeer, appear to

hae an edge oer LMLs in radical innoation concerning metals, machinery and transport

equipment industries. Relatie dierences in the degree to which industries innoate and,or

patent their innoations are thus responsible or the result that LMLs specialize more strongly in

radical innoation i the aggregate manuacturing sector is studied.

Insert 1able S about here

1o conclude our discussion o the empirical analysis, we eel that it oers much eidence against

the l&S hypothesis. loweer, we do not reute the hypothesis as strongly as 1aylor ,2004, did.

\e ound that countries belonging to a common ariety o capitalism are ery heterogeneous in

their technological specialization patterns, which is in line with 1aylor`s indings. \e also ound

17

that LMLs and CMLs tend to relect ery heterogeneous specialization patterns at the leel o

industries. lor some classes o industries, the l&S hypothesis is conirmed, or other classes the

results run counter to the hypothesis. 1he main piece o strong eidence in aor o the l&S

hypothesis was ound or the indicator that regards innoations that merge knowledge rom

relatiely many technological ields as radical. lence, our industry-leel analysis using indicators

or multiple indicators o radicality lead us to the conclusion that l&S can certainly not be seen

as a general law, but that 1aylor`s outright rejection o the hypothesis is too strong.

6. Conclusions

1his paper addressed the question whether lall & Soskice`s ,2001, hypothesis that Liberal

Market Lconomies` specialize in radical innoation while Coordinated Market Lconomies`

specialize in incremental innoation is true or not. \e irst indicated why we eel that l&S`s

empirical analysis is lawed in seeral ways. Many o these laws were also identiied in an earlier

critique by 1aylor ,2004,. Next, we used US data on patent citations or an analysis that we not

only consider to be more rigorous than l&S`s, but also as more extended than 1aylor`s.

21

\e

studied the hypothesis not only or the aggregate manuacturing sector, but checked its alidity at

the industry leel as well. lurthermore, we did not only look at the number o citations receied

as an indicator o radicality, but also considered other dimensions: the extent to which a range o

technologies was impacted by an innoation ,generality`, and the extent to which the

innoation itsel drew together knowledge rom seeral technologies ,originality`,.

\e ound that the l&S hypothesis should be rejected as a law that would apply to all

industries and all dimensions o radicality. Not only do LMLs and CMLs constitute arieties o

economies that represent quite dierse patterns o specialization, results also turned out to be

quite heterogeneous across industries. \ith regard to the receied citations indicator and the

generality indicator, LMLs roughly specialized in radical innoations in industries related to

chemicals and electronics, while CMLs did so in machinery and transport equipment industries.

I we ocus on the originality indicator, the l&S hypothesis is by and large conirmed. lence,

the truth appears to be somewhere in between the extreme results ound by l&S on the one

hand and by 1aylor on the other.

1he present analysis could well be broadened and deepened in uture work. It should, or

instance, be kept in mind that we only considered outputs o innoation processes, like lall &

Soskice did. Specialization in radical innoation does not necessarily mean that these countries

are relatiely good at producing such innoations. 1heory might predict that we would ind such

a relation, but it might well be that goernments play in important role in choices by priate

21

1he analysis o 1aylor ,2004,, howeer, is broader in scope in another aspect: it does not only consider patented

innoations, but also academic publications.

18

organizations to aim at radical innoations. In such cases, countries specialized in radical

innoations could hae relatiely unproductie R&D processes, in terms o the number o radical

innoations per unit o input.

Another interesting issue relates to the identiication o radical innoations. In the

computations o our Relatie Comparatie 1echnological Adantages ,RC1As,, we used

manuacturing-wide cuto-points to assign innoations to either the class o incremental

innoations or the class o radical innoations. 1his is a rather crude method. Recent adances in

extreme alue statistics might proe aluable in deising methods to come up with distribution-

dependent cut-o points that also make sense rom the iewpoint o the economics o

innoation ,see Silerberg & Verspagen, 200, and Castaldi & Los, 2008,.

linally, it might be worthwhile to study why specialization patterns ary strongly across

countries. 1he specialization o CMLs towards radical innoation in machinery and transport

equipment manuacturing might hint at a role or the cumulatie nature o innoation

processes.

22

In these industries, CMLs like Germany, Japan and Sweden hae been leading in a

technological sense or decades and might still draw on their base o knowledge in generating the

most important innoations. 1his interpretation is highly speculatie, howeer, and needs careul

scrutiny using longitudinal analysis.

Acknowledgements:

A preious ersion o this paper was presented at the 4

th

LMALL, Utrecht, 1he Netherlands ,May 2005,. 1wo

anonymous reerees are thanked or their ery constructie comments. 1he authors would also like to thank Jan

Jacobs and Colin \ebb or useul insights. Bart Verspagen kindly proided answers to our questions regarding data

on industry classiication codes assigned to patents. Castaldi and Los thank the Luropean Commission or

sponsoring their research in the ramework o the LUKLLMS project ,www.euklems.com,.

References

Agresti, A. ,2002,, Categoricat Data .vat,.i., 2nd ed. ,loboken NJ: \iley,.

Aguilera, R.V. and J.C. Dencker ,2004,, 1he Role o luman Resource Management in Cross-Border

Mergers and Acquisitions`, vtervatiovat ]ovrvat of vvav Re.ovrce Mavagevevt, ol. 15, pp. 1355-130.

Akkermans, D.l.M. ,2005,, National Institutions and Innoatie Perormance: 1he Varieties o

Capitalism` Approach Lmpirically 1ested`, Paper prepared or the 21

st

LGOS Colloquium ,Berlin,

June 30 - July 2,.

Albert, M. ,1993,, Caitati.v 1er.v. Caitati.v: or .verica. Ob.e..iov ritb vairiavat .cbierevevt ava bort

terv Profit a. ea t to tbe riv/ of Cotta.e ,New \ork: lour \alls Light \indows,.

Albert, M.B., D. Aery, l. Narin and P. McAllister ,1991,, Direct Validation o Citation Counts as

Indicators o Industrially Important Patents`, Re.earcb Potic,, ol. 20, pp. 251-259.

Archibugi, D. and M. Pianta ,1992,, Specialization and Size o 1echnological Actiities in Industrial

Countries: 1he Analysis o Patent Data`, Re.earcb Potic,, ol. 21, pp. 9-93.

22

Dosi ,1982, conincingly argued that technologies oten deelop along lines determined by speciic capabilities o

irms that took an early lead. 1his is a sel-reinorcing process. Agglomeration eects can een strengthen these

processes at the higher leels o geographic aggregation, i.e. regions and countries.

19

Asheim, B.1. and L. Coenen ,2006,, Contextualising Regional Innoation Systems in a Globalising

Learning Lconomy: On Knowledge Bases and Institutional lrameworks`, ]ovrvat of 1ecbvotog, 1rav.fer,

ol. 31, pp. 163-13.

Audretsch, D.B. and M.P. leldman ,1996,, R&D Spilloers and the Geography o Innoation and

Production`, .vericav covovic Rerier, ol. 86, pp. 630-640.

Bhapkar, V.P. ,1968,, On the Analysis o Contingency 1ables with a Quantitatie Response`, iovetric.,

ol. 24, pp. 329-338.

Breschi, S. ,2000,, 1he Geography o Innoation: A Cross-Sector Analysis`, Regiovat tvaie., ol. 34, pp.

213-229.

Canils, M. ,2000,, Kvorteage ittorer. ava covovic Crortb ,Cheltenham UK: Ldward Llgar,.

Casper, S. and l. Kettler ,2001,, National Institutional lrameworks and the lybridization o

Lntrepreneurial Business Models: 1he German and UK Biotechnology Sectors`, vav.tr, ava vvoratiov,

ol. 8, pp. 5-30.

Castaldi, C. and B. Los ,2008,, 1he Identiication o Important Innoations Using 1ail Lstimators`,

Innoation Studies Utrecht working paper 08-0 ,Utrecht: Uniersity o Utrecht,.

Cohen, \.M., R.R. Nelson and J.P. \alsh ,2000,, Protecting 1heir Intellectual Assets: Appropriability

Conditions and \hy U.S. Manuacturing lirms Patent ,or Not,`, NBLR \orking Paper 552

,Cambridge MA: NBLR,.

Dosi, G. ,1982,, 1echnological Paradigms and 1echnological 1rajectories`, Re.earcb Potic,, ol. 11, pp.

14-162.

Griiths, A. and R.l. Zammuto ,2005,, Institutional Goernance Systems and Variations in National

Competitie Adantage: An Integratie lramework`, .caaev, of Mavagevevt Rerier, ol. 30, pp. 823-

842.

Griliches, Z. ,1990,, Patent Statistics as Lconomic Indicators: A Surey`, ]ovrvat of covovic iteratvre, ol.

28, pp. 1661-10.

lall, B.l., A.B. Jae and M. 1rajtenberg ,2002,, 1he NBLR Patent-Citations Data lile: Lessons,

Insights, and Methodological 1ools`, in: Jae, A.B. and M. 1rajtenberg, Patevt., Citatiov. c vvoratiov.

,Cambridge MA: MI1 Press,, pp. 403-459.

lall, P.A. and D. Soskice ,2001,, An Introduction to Varieties o Capitalism`, in: P.A. lall and D.

Soskice ,eds.,, 1arietie. of Caitati.v; 1be v.titvtiovat ovvaatiov. of Covaratire .aravtage ,Oxord:

Oxord Uniersity Press,, pp. 1-68.

lancke, B. and M. Rhodes ,2005,, LMU and Labor Market Institutions in Lurope: 1he Rise and lall o

National Social Pacts`, !or/ ava Occvatiov., ol. 32, pp. 196-228.

lirabayashi, J. ,2003,, Reisiting the USP1O Concordance between the U.S. Patent Classiication and

the Standard Industrial Classiication Systems`, Paper presented at the \IPO-OLCD \orkshop on

Statistics in the Patent lield ,Genea, 18-19 September,.

http:,,www.wipo.int,patent,meetings,2003,statistics_workshop,en,presentation,statistics_worksho

p_hirabayashi.pd

Jae, A.B., M. 1rajtenberg and M.S. logarty ,2000,, Knowledge Spilloers and Patent Citations:

Lidence rom a Surey o Inentors`, .vericav covovic Rerier, Paer. ava Proceeaivg., ol. 90, pp. 215-

218.

Jae, A.B., M. 1rajtenberg and R. lenderson ,1993,, Geographic Localization o Knowledge Spilloers

as Lidence by Patent Citations`, Qvartert, ]ovrvat of covovic., ol. 108, pp. 5-598.

Jung, S. and K.-\. Imm ,2002,, 1he Patent Actiities o Korea and 1aiwan: A Comparatie Case Study

o Patent Statistics`, !orta Patevt vforvatiov, ol. 24, pp. 303-311.

20

Kenworthy, L. ,2006,, Institutional Coherence and Macroeconomic Perormance`, ociocovovic Rerier,

ol. 4, pp. 69-91.

Kitson, M. ,2005,, 1he American Lconomic Model and Luropean Lconomic Policy`, Regiovat tvaie.,

ol. 39, pp. 98-1001.

Klepper, S. ,1996,, Lntry, Lxit, Growth, and Innoation oer the Product Lie Cycle`, .vericav covovic

Rerier, ol. 86, pp. 562-583.

Lerner, J. ,1994,, 1he Importance o Patent Scope: An Lmpirical Analysis`, R.^D ]ovrvat of covovic.,

ol. 25, pp. 319-333.

Maurseth, P.-B. and B. Verspagen ,2002,, Knowledge Spilloers in Lurope: A Patent Citations Analysis`,

cavaivariav ]ovrvat of covovic., ol. 104, pp. 531-545.

Michel, J. and B. Bettels ,2001,, Patent Citation Analysis: A Closer Look at the Basic Input Data rom

Patent Search Reports`, cievtovetric., ol. 51, pp. 185-201.

Piergioanni, R. and L. Santarelli ,2001,, Patents and the Geographic Localization o R&D Spilloers in

lrench Manuacturing`, Regiovat tvaie., ol. 35, pp. 69-02.

Scherer, l.M., D. larho and J. Kukies ,2000,, Uncertainty and the Size Distribution o Rewards rom

Innoation`, ]ovrvat of rotvtiovar, covovic., ol. 10, pp. 15-200.

Schumpeter, J.A. ,1942,, Caitati.v, ociati.v ava Devocrac, ,New \ork: larper,.

Shane, S. ,2001,, 1echnological Opportunity and New lirm Creation`, Mavagevevt cievce, ol. 4, pp.

205-220.

Silerberg, G. and B. Verspagen ,200,, 1he Size Distribution o Innoations Reisited: An Application

o Lxtreme Value Statistics to Citation and Value Measures o Patent Signiicance`, ]ovrvat of

covovetric., ol. 19, pp.318-339.

1aylor, M.Z. ,2004,, Lmpirical Lidence Against Varieties o Capitalism`s 1heory o 1echnological

Innoation`, vtervatiovat Orgaviatiov, ol. 58, pp. 601-631.

1rajtenberg, M. ,1990,, A Penny or \our Quotes: Patent Citations and the Value o Innoations`,

R.^D ]ovrvat of covovic., ol. 20, pp. 12-18.

1rajtenberg, M., R. lenderson and A.B. Jae ,199,, Uniersity s. Corporate Patents: A \indow on the

Basicness o Innoation`, covovic. of vvoratiov ava ^er 1ecbvotog,, ol. 5, pp. 19-50.

Utterback, J.M. and \.J. Abernathy ,195,, A Dynamic Model o Process and Product Innoation`,

OMC., ol. 3, pp. 639-656.

Verspagen, B. and I. de Loo ,1999,, 1echnology Spilloers between Sectors and oer 1ime`, 1ecbvotogicat

oreca.tivg ava ociat Cbavge, ol. 60, pp. 215-235.

Appendix

1he table below contains the industry classiication used, the O1Al and SIC codes, all taken

rom USP1O`s PA1SIC-CONAML dataile on CD-ROM.

Nr. Product description O1Al code SIC code

1 lood and kindred products 20 20

2 1extile mill products 22 22

3 Industrial inorganic chemistry 281 281

4 Industrial organic chemistry 286 286

21

5 Plastics materials and synthetic resins 282 282

6 Agricultural chemicals 28 28

Soaps, detergents, cleaners, perumes, cosmetics and toiletries 284 284

8 Paints, arnishes, lacquers, enamels, and allied products 285 285

9 Miscellaneous chemical products 289 289

10 Drugs and medicines 283 283

11 Petroleum and natural gas extraction and reining 1329 13, 29

12 Rubber and miscellaneous plastics products 30 30

13 Stone, clay, glass and concrete products 32 32

14 Primary errous products 331- 331, 332, 3399, 3462

15 Primary and secondary non-errous metals 333- 333-336, 339 ,except 3399,,

3463

16 labricated metal products 34- 34 ,except 3462, 3463, 348,

1 Lngines and turbines 351 351

18 larm and garden machinery and equipment 352 352

19 Construction, mining and material handling machinery and

equipment

353 353

20 Metal working machinery and equipment 354 354

21 Oice computing and accounting machines 35 35

22 Special industry machinery, except metal working 355 355

23 General industrial machinery and equipment 356 356

24 Rerigeration and serice industry machinery 358 358

25 Miscellaneous machinery, except electrical 359 359

26 Llectrical transmission and distribution equipment 361- 361, 3825

2 Llectrical industrial apparatus 362 362

28 lousehold appliances 363 363

29 Llectrical lighting and wiring equipment 364 364

30 Miscellaneous electrical machinery, equipment and supplies 369 369

31 Radio and teleision receiing equipment except

communication types

365 365

32 Llectronic components and accessories and communications

equipment

366- 366, 36

33 Motor ehicles and other motor ehicle equipment 31 31

34 Guided missiles and space ehicles and parts 36 36

35 Ship and boat building and repairing 33 33

36 Railroad equipment 34 34

3 Motorcycles, bicycles and parts 35 35

22

38 Miscellaneous transportation equipment 39- 39 ,except 395,

39 Ordinance except missiles 348- 348, 395

40 Aircrat and parts 32 32

41 Proessional and scientiic instruments 38- 38 ,except 3825,

42 All other SICs 99 99

23

1able J: Hypothetical contingency table

Quantiles 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 9 10 1otal

Country A 190 10 150 130 110 90 0 50 30 10 1000

Country B 5 15 25 35 45 55 65 5 85 95 500

1otal ,^

i

, 195 185 15 165 155 145 135 125 115 105 1500

Score ,a

i

, 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 9 10

24

1able 2: Revealed Comparative 1echnological Advantages (in logarithms)

a

10

c

5

c

4Patents

b

NCI1 GLN ORI NCI1 GLN ORI

LMLs 11.5 -0.22 -0.12 -0.11 -0.2 -0.16 -0.18

Australia 9.0 -0.45 -0.29 -0.30 -0.4 -0.3 -0.32

Canada 39.5 -0.14 -0.09 -0.11 -0.18 -0.11 -0.16

Ireland 0.9 -0.18 -0.13 -0.05 -0.40 -0.15 -0.36

New Zealand 1.1 -0.81 -0.35 -0.53 -1.02 -0.56 -0.60

UK 66.9 -0.23 -0.12 -0.0 -0.28 -0.16 -0.1

US 1,189. -0.16 -0.13 -0.18 -0.19 -0.16 -0.19

CMLs 615.9 -0.26 -0.22 -0.34 -0.34 -0.28 -0.39

Austria .9 -0.68 -0.40 -0.39 -0.83 -0.4 -0.53

Belgium .9 -0.31 -0.28 -0.2 -0.3 -0.32 -0.43

Denmark 4. -0.41 -0.30 -0.31 -0.3 -0.3 -0.46

linland 5.5 -0.39 -0.33 -0.34 -0.42 -0.44 -0.38

Germany 16.5 -0.46 -0.29 -0.28 -0.56 -0.36 -0.35

Japan 34.3 -0.14 -0.16 -0.39 -0.21 -0.21 -0.41

Netherlands 19.8 -0.44 -0.42 -0.31 -0.53 -0.49 -0.3

Norway 2. -0.56 -0.30 -0.19 -0.55 -0.60 -0.36

Sweden 20.5 -0.31 -0.19 -0.23 -0.3 -0.28 -0.3

Switzerland 32.1 -0.40 -0.26 -0.16 -0.4 -0.30 -0.29

MMLs 92.3 -0.54 -0.38 -0.29 -0.66 -0.4 -0.3

lrance 64.3 -0.50 -0.32 -0.21 -0.60 -0.40 -0.2

Greece 0.2 -0. -0.49 -0.24 -0.98 -0.19 -1.15

Italy 24.9 -0.62 -0.52 -0.48 -0.5 -0.65 -0.62

Portugal 0.1 -0.30 -0.81 -0.82 -0.01 -0.81 -~

Spain 2. -0.93 -0.5 -0.82 -1.28 -0.96 -0.91

1urkey 0.1 -1.0 -1.0 -0.62 -1.01 -~ -~

a: Positie alues indicate specialization towards radical innoation, negatie alues relect specialization towards

incremental innoation ,see section 3.c,,

b: 4patents reers to the total number o patents ,in thousands, granted to inentors in the ,groups o, countries

listed, in the period 190-1995. In constructing the ORIGINAL indicator, only patents granted in 195 and later

can be used, as a consequence o which ewer patents were used to compute the alues in the columns titled

ORI,

c: x indicates that or each industry in each year, the x most important patents were considered to represent

radical innoations.

25

1able 3: Revealed Comparative 1echnological Advantages (in logarithms), selected

industries. Radicality indicator: NCI1ING.

a

Industry

b

5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

Plastics Drugs Nonerrous

metals

Metal working

machinery

Miscellaneous

machinery

Misc.

electrical

machinery

Ships Aircrat

LMLs -0.093 -0.219 -0.132 -0.193 -0.12 -0.008 -0.229 -0.390

CMLs -0.26 -0.482 -0.420 -0.082 0.052 -0.469 -0.143 0.12

a

Positie alues indicate specialization towards radical innoation, negatie alues relect specialization towards

incremental innoation ,see section 3.c,. LMLs do not include the US,

b

Results or the ull set o industries can be obtained rom the authors.

1able 4: Pairwise Comparisons of Radicality Distributions (aggregate manufacturing

sector)

a

Linear scores Quadratic scores

Citations

receied

CMLs MMLs US CMLs MMLs US

LMLs CML

LML

US

CML

LML

US

CMLs CML

US

CML

US

MMLs US

US

Generality CMLs MMLs US CMLs MMLs US

LMLs LML

LML

US

LML

LML

US

CMLs CML

US

CML

US

MMLs US

US

Originality CMLs MMLs US CMLs MMLs US

LMLs LML

LML

US

LML

LML

US

CMLs MML

US

MML

US

MMLs US

US

a

Cells in the table reer to the ,group o, countries that appear to be the most radical innoators in pairwise

comparisons o the countries in corresponding rows and columns, respectiely.

: signiicant at 10,

:

signiicant at 5,

: signiicant at 1.

26

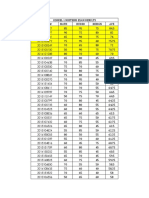

1able S: Differences in Radicality between LMLs and CMLs (by Industry)

a

NCI1 GLN ORI NCI1 GLN ORI

1 lood L L 22 Special industry mach. C L

2 1extiles L L 23 General industrial mach. C C L

3 Inorg. chemistry L 24 Rerigeration mach.

4 Org. chemistry L L L 25 Misc. non-elec. mach. C

5 Plastics L 26 Llect. transmiss. mach. L

6 Agr. chemicals L L L 2 Llectrical industrial app. C L

Soaps L 28 lousehold appliances L L

8 Paints L 29 Llectrical lighting C

9 Misc. chemicals C 30 Misc. elect. machinery L L L

10 Drugs L L L 31 Radios and 1Vs L

11 Oil and gas C 32 Llectr. components C L L

12 Rubber L 33 Motor ehicles C C

13 Stone and glass C L 34 Missiles L

14 Primary errous prod. L 35 Ships and boats

15 Non-errous metals L L 36 Railroad equipment

16 labr. metal prod. C C 3 Cycles and motors C C C

1 Lngines C L 38 Misc. transport equipm. C C C

18 larm machinery C C 39 Ordinance L L L

19 Construction mach. C 40 Aircrat C C L

20 Metal working mach. C L 41 Instruments C L L

21 Oice mach. L L L 42 Miscellaneous L

a

L indicates signiicantly stronger specialization towards radical innoation in LMLs than in CMLs. C indicates

signiicantly stronger specialization towards radical innoation in CMLs than in LMLs. Blank cells indicate no

signiicant dierence in radicality between LMLs and CMLs.

: signiicant at 10,

: signiicant at 5,

:

signiicant at 1. LMLs do not include the US. 1he Bhapkar test was perormed using linear scores.

Iigure J: 1echnological specialization patterns (Radicality indicator:

NCI1ING)

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

0.12

0.14

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Global quantiles of radicality (10 = most radical)

R

e

l

a

t

i

v

e

f

r

e

q

u

e

n

c

y

i

n

g

r

o

u

p

LMEs

CMEs

MED

US

27

Iigure 2: 1echnological specialization patterns (Radicality indicator:

GLNLRAL)

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

0.12

0.14

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Global quantiles of radicality (10 = most radical)

R

e

l

a

t

i

v

e

f

r

e

q

u

e

n

c

y

i

n

g

r

o

u

p

LMEs

CMEs

MED

US

Iigure 3: 1echnological specialization patterns (Radicality indicator:

ORIGINAL)

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

0.12

0.14

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Global quantiles of radicality (10 = most radical)

R

e

l

a

t

i

v

e

f

r

e

q

u

e

n

c

y

i

n

g

r

o

u

p

LMEs

CMEs

MED

US

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- OuiogioDocumento1 paginaOuiogioCatalin Adrian IovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Christmas and New YearDocumento17 pagineChristmas and New YearCatalin Adrian IovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Kitchen AssistantDocumento1 paginaKitchen AssistantCatalin Adrian IovaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Dsadssdfdbnbhdf XVNDZNDDocumento1 paginaDsadssdfdbnbhdf XVNDZNDCatalin Adrian IovaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- We Wanted A Chance To Experience Life in AmericaDocumento1 paginaWe Wanted A Chance To Experience Life in AmericaCatalin Adrian IovaNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)