Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Pollard Eta Factory Village

Caricato da

Asier ArtolaDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Pollard Eta Factory Village

Caricato da

Asier ArtolaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Factory Village in the Industrial Revolution Author(s): Sidney Pollard Source: The English Historical Review, Vol.

79, No. 312 (Jul., 1964), pp. 513-531 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/560991 . Accessed: 12/03/2014 13:24

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The English Historical Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I964

5I 3

The Factory Village in the Industrial Revolution'

I

HE question of the standard of living during the industrial revolution continues to be a subject of acute controversy.2 As always, however, the scene of battle is shifting during the contest, and it is nowadays increasingly recognized that no single answer can be given, since different classes and industries fared differently, while at the same time the issue of the quality of life in the new factory towns will have to remain largely a matter of subjective judgment. One comer of this controversy is, or ought to be, the conditions prevailing in the company towns and villages, for here some of the main developments of the industrial revolution were epitomized: here were whole townships under the social and economic control of the industrialist, their whole raisond'6trehis quest for profit, their politics and laws in his pocket, the quality of their life under his whim, their ultimate aims in his image. What is to our immediate purpose, they have in the past raised as much controversy as the issue of the industrial revolution itself. At their best, they were, or could have become, models of social progress, the creations of men with a conscience and some social idealism, vehicles for transferring at least some of the benefits of industrial invention and work to the mass of the working population. Such was Robert Owen's New Lanark. But others were typefied by the owner who oppressed Robert Blincoe and his fellow apprentices, or the master of the mill at Backbarrow who obtained notoriety by turning his apprentices loose in a period of slack trade, to beg their T

1 This essay is part of a larger study on industrial management in the industrial revolution, which has been made possible by a grant by the Houblon-Norman Fund. 2 The most recent contributions are: R. M. Hartwell, 'The Rising Standard of Living in England, 80oo-850 ', Econ. Hist. Rev. (2nd ser.), xiii (I96) ; E. J. Hobsbawm, ' The British Standard of Living, I790-1850 ', ibid. x (I957) and discussion in ibid. xvi/i (I963) ; A. J. Taylor, 'Progress and Poverty in Britain, I780-850 : A Reappraisal', History xlv (I960). VOL. LXXIX--NO. CCCXII KK

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

514

THE FACTORY

VILLAGE

July

way into their home parishes,1 and these were eloquently described by the Hammonds.2 Historians today are increasingly inclined to see them, not in terms of social conscience, but in terms of managerial necessity. Smelser, in his recent perceptive study of the cotton industry, was driven to the conclusion that, great though the outward difference was between the flogging masters and the model community builders, 'from the standpoint of control of labour . . ., both types of factory management display a concern with the enforcement of discipline'. 'The much publicized evils of the factory system', concluded another historian 'were symptoms ofmanagerialinefficiency and inadequate capital resources rather than the inevitable concomitant of factory employment.'3 The importance of this aspect has been underrated in the past, and it is the object of this paper to and examine provide a new evaluation of it in the period up to 830o, some of the consequences of this approach. II The large scale entrepreneur of the day had to manage his firm personally, in the virtual absence of a managerial, clerical or administrative staff,4 as well as without the indispensable aids to modern management, from telephones and typewriters upwards. He wrote his own letters, visited his own customers, and belaboured his men with his own walking-stick.5 Yet his range of responsibilities was much wider than that of today's entrepreneur, who is concerned almost exclusively with the activities inside the factory, with buying, producing and selling. In the early years of industrialization many outside services now taken for granted or dealt with by the single action of paying taxes, had to be provided by the large manufacturer himself. Among the most important were those creating the 'infrastructure ' of an undustrial economy. There were, first of all, the costly means of transport. The large collieries on the Tyne and Wear, it is

1 SelectCommittee on the Children Parl. Papers I8I6, iii. Employedin the Manufactories, i8I, 295, ev. John Moss, pp. 290-I, ev. Wm Travers; J. D. Marshall, Furnessand the IndustrialRevolution (Barrow-i.-F., I 958), pp. 52-53. ' 2 The new towns, they wrote in a well-known passage, were not so much towns as barracks: not the refuge of a civilization but the barracks of an industry .... They were settlements of great masses of people collected in a particular place because their fingers or their muscles were needed on the brink of a stream here or at the mouth of a furnace there. These people were not citizens of this or that town, but hands of this or that master.' J. L. and Barbara Hammond, The TownLabourer(1919), pp. 39, 40. 3 N. J. Smelser, Social Changein the IndustrialRevolution(1959), p. 05 ; J. D. Chambers,' Industrialization as a Factor in Economic Growth: England, I700-900 ', in Contributions To theFirst International of Economic Conference History(Paris, 960), p. 208. Cf. also M. Dobb, Studiesin theDevelopment of Capitalism( 947 edn.), p. 266. 4 The question of the managerial staff is of major importance by itself, and I hope to deal with it elsewhere. 6 Neil McKendrick, ' Josiah Wedgwood and Factory Discipline ', HistoricalJournal, iv (I96) ; Charles Wilkins, The History of the Iron, Steel, Tinplate, and Other Tradesof Wales(Merthyr Tydfil, I903), p. 69.

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1964

IN THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

515

well known, provided their own rail systems from about I605 onwards; by I725, one line was 5 miles long and within a generation some local lines reached lengths of 8-Io miles. Hetton colliery in I826-7 had an 8-mile long railway, three steam locomotives, six stationary engines and five brake contrivances, including inclined planes.1 Elsewhere, Whingill colliery at Whitehaven, for example, had Io miles of iron railroads to keep up by 1827, and the duke of Norfolk's Sheffield collieries some 8 miles. Some iron works were similarly placed : the Merthyr tramroad system maintained by the local ironmasters extended to 40 miles, and by 183 , it was reputed,

to 120 miles.2

In the canal era, the duke of Bridgewater's agent had to supervise the building of the premier canal as part of his duties of running the Worsley collieries, besides managing an extensive agricultural estate, draining marshes, dovetailing a tree planting programme and generally supervising the erratic innovating genius of Brindley.3 Many other coalowners found canals indispensable and had to build them; elsewhere the canals built by Wedgwood, by the Carron works, the Horsley ironworks and by Samuel Oldknow have long since become standard examples in the textbooks. Other entrepreneurs, again, had to build ports and harbours. This includes the major coal magnates, in West Cumberland, the Lowthers, the Curwens and the Stenhouses, as well as the Anglesea copper mining companies, which had to create the harbour of Amlwch; they, indeed, also owned much shipping, as did Carron. Others, again, built roads: Arkwright's small mill at Bakewell spent Ci,ooo on roadmaking, besides the personal contributions of the owners to the County's turnpike system.4 Other enterprises had to go in for large scale farming mainly for the sake of food for workers, fodder for the horses (the works transport), pit props or timber for fuel. Ambrose Crowley devoted much

1 C. E. Lee, ' The World's Oldest Railway ', Transactions Society,xxv of the Newcomen ( Tyneside Tramroads of Northumberland', ibid. xxvi (I947-9), and 'The Aeliana (4th ser.), xxix (95I), Wagonways of Tyneside', Archaeologia I35 ff. ; C. F. Dendy Marshall, A History of BritishRailwaysdownto the Year 1830 (I938), p. 25; R. A. Mott, 'Abraham Darby (I and II) and the Coal-Iron Industry ', Trans. Newc. Soc. xxxi (I95 7-9). 88-89; R. L. Galloway, Annals of Coal MiningandtheCoal Trade(1898), p. 284. 2 Mechanics' Magazine,25 June 1831 ; Stanley Mercer, ' Trevethick and the Merthyr Tramroad ', Trans.Newc. Soc. xxvi (I947-9), 90; also ibid.xxix. 6; Norfolk Muniments (MSS., Sheffield City Library), S.232; Charles Wilkins, The South Wales Coal Trade (Cardiff, I888), p. I87. 3 Edith Estate I78o- 8 o (M.A. Malley, TheFinancialAdministration of theBridgewater Thesis, Manchester, ?i929), pp. 119, I46 ff. 4 M. J. Norris, 'The Struggle for Carron', ScottishHistoricalReview,xxxvii (I958), in Lancashire andNorth Wales, I76o-i 8y, (Ph.D. 137; J. R. Harris, TheCopperIndustry Thesis, Manchester, n.d.) p. 240; O. Wood, Coal, Iron and Shipbuildingof West Cumberland 1I70-g114 (Ph.D. Thesis, London, I952), pp. 5-6, 26-28, 41 ; C. M. C. Bouch and G. P. Jones, A ShortEconomic andSocialHistoryof theLake Counties o00-I 830 (Manchester, 1961), pp. 227-8 ; R. H. Campbell, CarronCompany (Edinburgh and London, 1961), pp. II5-I8 ; H. M. Mackenzie, 'The Bakewell Mill and the Arkwrights ', Arch and Nat. Hist. Society,lxxix (959), 64. Journ.Derbyshire

(I945-7),

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

5i6

THE FACTORY

VILLAGE

July

energy to his works farm, and examples in the period 1770- 830 may be found in a wide range of industries represented by Plymouth and Cyfarthfa ironworks, Litton mill, Greg's at Styal, Oldknow at Mellor, the Backbarrow Co., the Swinton pottery, the Cheadle New Wire Co., Woolaton pits, the Quaker Lead Co., Darley Abbey cotton mills, and the Parys Mine Co. The early cotton mills, again, had to be their own engineers. Thus the New Lanark machine shop cost annually C8,ooo, employing 87 men, and the works at Deanston were scarcely less extensive ; Heathcoat's, removing to an engineering backwater at Tiverton, had an engineering branch which soon acquired its own reputation, building agricultural machinery.1 Finally, the early entrepreneurs frequently had to arrange for their own security. It was not only in the barbarian Highlands that troops had to be provided in the absence of reliable local police, or in the mining areas where it was said that there were 'strong, healthy and resolute men, setting the law at defiance, no officer dared to execute a warrant against them '.2 The introduction of new machinery such as cotton frames, gig mills or power looms, could cause riots and so could ordinary strikes and food shortages. Some managers were then turned into military officers on top of their other duties. All these, however, were tasks which might face the men managing factories and mines anywhere in Britain. We must now turn to those which fell especially on the men who set up in isolated villages and created, in effect, company towns and villages. III The first and most obvious need was to provide houses. In Scotland, in particular, the decision to establish a large works in the open country was taken to be synonymous with the need for new housing: Adam Bogle, managing the Blantyre mills, calculated simply that the working of double shifts would involve Monteith, Bogle & Co. in an expenditure of ?I 5-20,000 on new houses. But in England, too, Isaac Hodgson of Lancaster assumed that if he wanted to expand his cotton mill, he would have to build more houses for his workers, while Brameld took it for granted thathe could re-open the Swinton pottery in 181o only if Earl Fitzwilliam built

1 Robert Owen, Life of Owen(1920 edn.), p. 187, and A New View of Society(1927 edn.), p. I7 ; H. G. MacNab, The New Views of Mr. Owenof Lanark ImpartiallyExamined (I 89), pp. 67, 07 ; Sir John Sinclair (Old) StatisticalAccountof Scotlandxv (EdinFirst Report(referredto henceforth as burgh, 1795), p. 36 ; FactoriesInquiry Commission, Factories Commission), Parl. Papers, I833, xx, Sec. Ai, 65 ; William Felkin, A History of the Machine-Wrought HosieryandLace Manufactures (1867), p. 264; J. D. Marshall, op. cit. p. 5I. 2 Robert Edlington, A Treatiseon the Coal Trade(I8I3), p. I8.

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I964

IN THE INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

517

cottages for his workers.' The north-eastern collieries, as a rule, provided cottages ('hovels ') for their men, who would vacate them when changing their employment, and each mining village was simply a group of pits, with its attached colliers' houses. Cottages entered into normal capital costs, and were included in the standard yearly miners' bond. Cumberland, as always, followed the Tyneside practice closely.2 A list of large works providing their own attached cottage estates or a controlling share of them reads like a roll-call of the giants of the industrial revolution. From Ambrose Crowley and Sir Humphrey Mackworth, the fore-runners at the turn of the century, and the Newlands (iron) Company and' New York ' a little later, the list includes, among English cotton mills, Hyde, Newton, Dukinfield, Cromford, Milford, Belper, Bakewell, Mellor, Staleybridge, Cressbrook, Backbarrow, Darley Abbey, Styal and Bollington, the Peels' settlements at Bury and the Horrocks's at Preston ; in Scotland, New Lanark, Deanston, Catrine, Blantyre, the Stanley Mills and in Belfast, Springfield. Among ironworks there was Carron, Ebbw Vale, Cwmavon, Dowlais, Plymouth, Nantyglo, Ketley, Butterley (Golden Valley and Ironville) and the Walkers of Masbro '. There was Benjamin Gott's in the woollen trade, and the Worsley complex of enterprises. In the copper industry, the Warmley Co. Charles Roe's and Morrison; in lead, Nent Head, Carrigill, Middleton, and Leadhills. There was Melingriffith in the tinplate trade, Tremadoc and Port Madoc in slate, and Etruria in pottery. In a few cases, workers were housed in one large block. Boulton put his workers in the top floor of the wings of the first block at Soho. At Paisley, John Orr housed thirty-five families in one building. At Neath, Sir James Morris's 'castellated lofty mansion, of a collegiate appearance, with an interior quadrangle, containing dwellings for forty families, all colliers, excepting one tailor and one shoemaker, who are considered as useful appendages to the fraternity ', had a higher reputation than Henry Houldsworth's block at Anderston, Glasgow, of which even Dr. Ure could find

1 Wentworth Woodhouse Muniments (MSS., Sheffield City Library), F. io6a; Houseof Lords Committee on Apprentices,Parl. Papers, I818, v. 214; S.C. on Childrenin andManufactures Manufacture, p. I69; cf. also David Loch, Essay on the Trade,Commerce of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1775), p. 47; D. F. Macdonald, Scotland's I770ShiftingPopulation, i8yo (Glasgow, 1937), pp. 62, 64; Anon., 'Some Glasgow Customers of the Royal Bank around i800 ', ThreeBanksReviewNo. 48 (I960), p. 39; Sinclair, loc. cit. p. 40. 2 E. Hughes, North CountryLife in the EighteenthCentury(I952), p. 257; Hylton Scott, ' The Miner's Bond in Northumberland and Durham', Proceedings of the Soc. of Antiquariesof Newcastle-upon-Tyne (4th ser.), xi (I947), 64; J. B. Simpson, Capital and Labourin Coal Mining(Newcastle, I900), p. 29; T. S. Ashton, ' The Coal-Miners of the Eighteenth Century', EconomicHistory i (1928), 311 ; John Holland, The History and Descriptionof Fossil Fuel, The CollieriesandCoal Tradeof GreatBritain ( 835), p. 293 ; 0. Wood, op. cit. pp. 42, 135.

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

5 8

TH3E

FACTORY

VIL;LAGE:

July

nothing better to say than that it was very healthy after ventilation had been put in.' At Merthyr Tydfil, a company town in many respects, though dominated by four iron companies rather than one, Crawshay, having monopolized all the likely building land round his works, leased it out to others, with disastrous results for the health and amenities of the area. Richard Hill, at neighbouring Plymouth, being too poor to build workers' cottages himself, had them built by a Bristol merchant who found the speculation most profitable.2 Few works outside the factory villages had large housing programmes. City firms might own a few houses for key workers, at best, and if small firms provided a row or two of cottages, these had no further social significance. According to the returns of the Factory Commission of 833, of 881 large firms, 299 gave no details, 414 made no housing provisions and I68 provided some houses.3 But of these, the majority provided a few only. The management of the housing property gave the villages their character and was usually symbolic of the employers' attitude to his workmen in general. Robert Owen began4 by building a second storey on to the New Lanark houses, having the dung-heaps cleared, and organizing a permanent cleansing service. Finlay's, at Deanston, offered prizes for the best-kept houses, and at least fourteen other works in Scotland reported in 1833 special incentives, or Company services, in cleaning and whitewashing their cottage property. Thomas Ashton's stone-built houses at Hyde, having at least four rooms, with pantry, a small backyard and a privy, were 'an object of wonder and admiration',5 and Samuel Greg paid special attention to housing in his model settlement at Bollington. At such exceptional firms as David Rattray's flax mills in Perthshire, workers lived rent free ; elsewhere rent was deducted from pay before pay-day. The works management, rather than a special housing manager, thus looked after the settlement and housing could be turned into a

1D. T. Williams, The EconomicDevelopmentof Swansea(Cardiff, 1940), pp. 175-6, quoting Walter Davies, GeneralView of Agricultureand DomesticEconomy of South Wales, (I815), i. 134-5 ; also G. G. Francis, TheSmeltingof Copperin the SwanseaDistrict (I881 edn.), p. 132 ; D. C. Webb, FourExcursions... in the Years18So and I8iI (81 2), p. 355 ; (Thomas Martyn) A Tour to South Wales (National Library of Wales MS. No. 1340, x80o), fo. 80; Factories Commission,Second Suppl. Report, Renfrewshire; Andrew Ure, The Philosophyof Manufactures (I835 edn.), p. 393. The Owenist settlement at Orbiston was also housed in a large four-storeyed block. W. H. G. Armytage, Heavens Below(1961), p. 97. 2 Wilkins, op. cit. p. andHistoricalDescription I49 ; T. Rees, A Topographical of South W'ales (I8I5), p. 646. 3 FactoriesCommission, Suppl. Report, part ii, P.P. 1834. xx. 4 Robert Dale Owen, Life of Owen,p. 84; Threading My Way (1874), pp. 71-72; G. D. H. Cole, RobertOwen(1925), p. 72. 5 Frances Collier, The Family Economyof the Workersin the CottonIndustryduringthe Period of the IndustrialRevolution1784-1833 (M.A. Thesis, Manchester, I921), p. I37; Ure, op. cit. p. 349 ; F. Hill, National Education(2 vols. 1836), p. I35 ; FactoriesCommission,First Report, D. 2, p. 83, Supplementary Report, part ii.

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

i964

IN THE INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

5I9

tool of discipline. Not only were evictions, for example in the coalfields, used to defeat strikes, but even as routine policy, the Worsley mines explicitly reserved the best houses for the best workers, and withdrew them when their discipline or obedience showed signs of falling off.1 In addition, the houses had of course to be made to pay, and this was not difficult when cottages cost about ?5 to build, rising from about ?40-45 in the seventeen-seventies to ?60 during the war inflation,2 while rents were 2s. to 3s. a week, and certain. With yields thus well over io per cent, housing accounts chalked up regular profits in most firms.3 IV In Scotland, by tradition, schools were provided in every parish, and even the less enlightened owners of flax mills round Aberdeen and Dundee, and of cotton mills round Glasgow and Paisley, provided at least school rooms and often the teaching also.4 In England and Wales school provision was rarer.5 It was again, largely confined to the entrepreneurs who were also community builders. In the textile areas schooling was particularly important, since the pupils were not the workers' children, but the ' hands ' themselves. Everywhere, however, it was partly subsidized, and partly paid for by the children themselves. In many villages much thought and effort went into the organization of the day and evening schools, and some were dovetailed with working hours and came under works discipline. Sunday schools had a far more important part to play, being largely designed to inculcate current middle-class morals and obedience, but they were widespread in the cities as well as in the factory villages.

1 Society and Increasing the Comfortsof the Poor, 4th Report for Betteringthe Condition (I798), p. 239. 2 Hugh Malet, The Canal Duke (Dawlish and London, I961), p. I65 ; Herculaneum Pottery Minute Book (Liverpool Central Library MSS., 380 M.D. 47), io March I807, 7 June, 6 Dec. 1814, 6 June x815, 2 April I8I6, 25 Nov. 18I7, 6 June 1820 ; Cyfarthfa MSS. (National Library of Wales), Box 12; Henry English, A Compendium ... relating to the Companies British Mines (1826), p. 120. formedfor working 3 P. Gaskell, The Manufacturing Population of England(1833), p. 348 ; R. S. Fitton and A. P. Wadsworth, The Strutts and the Arkwrights (Manchester, i958), p. 246 ; Factories First Report, A. I, pp. 92, 97; Cyfarthfa MSS., Box 12, Profit and Loss Commission, Accounts 1814, 1819, 1820 ; Select Committeeon Manufactures, Commerce and Shipping, Parl. Papers 1833, vi, QQ. 9800-2. Also Boulton and Watt MSS. (Birmingham Assay Office), Correspondence, Boulton to Thos. Loggan, 14 Dec. 1794; J. E. Cule, The FinancialHistory of MatthewBoulton,I7yJ9-I800 (M.Com. Thesis, Birmingham, I935), p. 191 ; John Horner, The Linen Tradeof Europeduringthe Spinning-Wheel Period (Belfast, I920), p. I05. 4 E.g. Replies to Questionnaire, FactoriesCommission, Supplementary Report II, and FirstReport, A. I : pp. I, 3, i8, 21, 30, 3I, 62, 65, 79, 92, 93, II ; A. 2 : pp. 35, 49, 73. 5 The educational provisions of the Act of 1802 remained a dead letter, and even those of 1833 had little immediate effect. Hill, op. cit. p. I29 ; G. Ward, ' The Education of Factory Child Workers, I833-I850 ', Economic History, iii (I935), IIo ff.

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

520

THE

FACTORY

VILLAGE

July

Dissenters among the community builders, like the Strutts, Newton Chambers or the Gregs, built chapels, others built churches, and Quakers, like Darby's, joined with many of their staff in regular religious meetings. At one extreme, Robert Owen provided out of his own pocket for a number of different sects, with none of whose teaching he agreed. At the other, Richard Crawshay laid it down that he 'wishes every Man to worship God his own way, but is no friend to new fanatick sectarys. The two establishments of Church and Presbytery afford choice enough for Humble Men to find their own way to God, Grace and Holy Spirit.'1 In some industries, as e.g. in the Cornish tin mines, in the dockyards, and in some South Wales Ironworks, medical assistance was commonly provided by a 2d. weekly deduction from wages.2 Elsewhere, I d., id., or even ?d. a week might be deducted, and Whitehaven miners paid 2zo a year to a surgeon in the mid-eighteenth At least as often, firms paid century 'for cureing burnt men'.3 either retainer or whenever surgeons direct, by they were called in. in attention. had Apprentices, particular, usually regular This service was usually accompanied by the support of Sick Clubs, and by pensions. Sick clubs were largely financed by the men themselves, but in numerous cases the employer, by virtue of a small or contingent contribution, had absolute control over the management of the Fund, directly or indirectly, and used it as a means of disciplinary control, by combination with a system of fines and rewards.4 Among the best-known works schemes were that of Matthew Boulton, copied widely, though leading to much dissatisfaction in Soho because of its autocratic government, and that of Curwen, establishedI786 at Workington and Harrington, as he proposed its extension to the whole country, in place of the Poor Law, in i8i6.5 In some firms, membership was compulsory, and deductions were made from wages for it.

1 Arthur the Darbysand Coalbrookdale (I953), p. 4; Raistrick, Dynasty of Ironfounders, e Co. Ltd. serialized in Thorna Short History of Newton Chambers H.E.E., Thorncliffe, cliffe News (I953 on), ii; Frances Collier, ' An Early Factory Community', Economic P.P. I833, vi, QQ. 11416-7 ; Fitton and History, ii (1930), Ix8 ; S.C. on Manufactures, ' One Wadsworth, p. Ioo ; National Library of Wales, MS. No. 2,873 17 Oct. I793; Formerly a Teacher at New Lanark ', RobertOwenat New Lanark (Manchester, i839), pp. 11-12. 2 Madeleine Elsas Letters, 1782-1860 (ed.) Ironin the Making: Dowlais Iron Company (Country Records Committee, Glamorgan, and Guest Keen Iron and Steel Co. I960), p. 72; Arthur Titley, ' Cornish Mining', Trans. Newc. Soc. xi (1930-1), 30; P.R.O. ADM 42/553; SelectCommittee on Paymentof Wages,Parl. PapersI842, ix, QQ. 3019 ff. 3 Galloway, Annals, p. 347; A. H. John, The IndustrialDevelopment of South Wales, Second 17yo-I8Xo (Cardiff, 1950), p. 86 ; Hill, op. cit. p. 137 ; Factories Commission, Report, P.P. I833, xxi, D. 2, p. 56; 0. Wood, p. I36. 4E.g. Marshall Papers (MSS., Brotherton Library, Leeds), No. 43, Articles io March I795 ; FactoriesCommission, First Report, C. I, pp. 46-47 ; Jean Lindsay, ' An Early Industrial Community. The Evans' Cotton Mill at Darley Abbey', Business History Review,xxxiv (1960), 299. 6 Erich Roll, An & WVatt, ... Boulton Early Experimentin Industrial Organisation i77f(i8oi), ii. I8o0 (9530), pp. 223-34; Stebbin Shaw, HistoryandAntiquitiesofStaffordshire

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I964

IN THE INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

52I

Some of these funds made death grants also and other firms paid pensions. Provision varied widely, from the derisory sum of Liz a year set aside by the Strutt's for compensation to accident victims at a time when there were 200 a year, to the average of ?8 a week paid out year after year, by the Mona Mine Co. to widows of men killed at work, to injured men, and to retired agents.' V The master of a factory town had the same ultimate objective as his counterpart, the town employer : he wanted his hands to work hard, reguarly and well, and he wanted them to abstain from rioting and from making use of what other bargaining power theypossessed. The town employer, however, could get by with simple model of worker psychology, in which money was the sole stimulant, and its operation encouraged by the convenient doctrine that the hands worked the better, the less they were paid. Some philosophers and some employees might well have emancipated themselves from this view by 175o,2 but in most factories the traditional view of the overriding dominance of the cash nexus took at least two or three more generations to break down.3 The man in charge of the factory village, on the other hand, was forced to take account of the worker's behaviour outside working hours, of his family, the likelihood of his migration, and of his attitude to the industrial system as a whole, often called by contemporaries his 'moral outlook'. At the same time, he had more tools at his disposal to mould his worker by moulding his environment and to impress his own system of morals on the whole factory community. Sometimes this took curious, almost unintelligible forms, as in the extraordinary preoccupation with bad language, and the length

Boulton(Cambridge, I937), p. 179; W. B. Crump (ed.), 121; H. W. Dickinson, Matthew The Leeds WoollenIndustry,I780-I820 (Leeds, I931), p. I87 ; Herbert Heaton, 'Benjamin Gott and the Industrial Revolution in Yorkshire', Ec. Hist. Rev., iii (I93I), 6i; John Lord, Capital andSteamPower(I923), p. 205 ; A. Raistrick, TwoCenturies of Industrial Welfare,The London(Quaker) Lead Company,I692-I90o (1938), pp. 47-48 ; Sir F. M. Eden, The State of the Poor (I797), pp. 78-80, I64-5 ; 0. Wood, op. cit. p. 44. 1 Fitton and Wadsworth, p. 253; Mona Mine MSS. (Univ. Coll. Bangor), Nos. in the TownandParish of 641, 2252, 3I74-5; John Rowlands, SocialandEconomic Changes AmlJwch, (M.A. Thesis, Wales (Bangor), I960), p. 273. Ir7o-I8;o 2 A. W. Coats, ' Changing Attitudes to Labour in the Mid-Eighteenth Century', Econ. Hist. Rev. (2nd ser.), xi (1958); E. S. Furniss, The Position of the Labourerin a Systemof Nationalism (N. York, I957 edn.), pp. 178 if. 3 New Lanark always excepted. E.g. Cole, Robert Owen, p. I05 ; Peter Gorb, 'Robert Owen as a Business Man ', Bulletinof the Business HistoricalSociety,xxv (I95 ), 144; J. Lord, op. cit. p. 226 ; Ure, op. cit. pp. 364-5 ; A. H. John, op. cit. pp. 70-72; Raistrick, Two Centuries, p. 22; P. Russell (ed.), EnglandDisplayed(1769), ii. 94; Lords Committeeon Apprentices, p. 24; Joseph Kulischer, Allgemeine Wirtschaftsgeschichte p. 30I ; L. Urwick and E. F. L. (Munich, I958 repr.), pp. 182-3 ; S.C. on Manufactures, Brech, The Making of ScientificManagement (I959 edn.), ii. ii. The banality of much later writing on management is anticipated in J. Montgomery, The Theory andPracticeof CottonSpinning(Glasgow, 1833), pp. 25I-3.

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

522

THE

FACTORY

VILLAGE

July

to wlhich the masters would go to prevent their children having any leisure whatever on Saturdays and Sundays.l But more typically, Robert Owen, Busby & Co. at Mearns, James Finlay at Ballindaloch Robert McGregor at New Kilpatrick, Joseph Stephenson at Antrim, the Blantyre and Deanston works took special measures and employed special staff to control the ' morals ' of their villages. The Board of the British Plate Glass Company, discussing the salary of its manager in 18 15, resolved that 'the moral order and regularity of the small community belonging to the works must be seen to enable the Committee to form a just estimate of the Superintendent's merits'. The Quaker Lead Company lauded for its social conscience, never dismissed anyone except those guilty of 'tippling, fighting, nightrambling, mischief and other disreputable conduct, or evidence of a thankless and discontented disposition '.2 Those dismissed were never taken on again and in effect, in those isolated mining villages, forced to starve or to emigrate. Discipline in the works and in the villages could not be separated: 'We have had a most uneasy time for many months past with our people,' complained Josiah Wedgwood, after the move to Etruria, 'they seem to have got a notion that as they are come to a new place with me they are to do what they please.'3 The vexed question of drink does, perhaps, show the link most clearly. Drunkenness was, in fact, the only cause of dismissal operating at New Lanark; it was equally seriously regarded by the Quaker Lead Co., by Marshall's of Leeds, and by other model employers.4 It was indeed, a perennial problem especially among skilled men, who were paid enough to be able to afford it, and who were scarce enough not to be sacked too easily. Boulton and Watt were repeatedly troubled by it as it affected some of their best engineers, and at one strike at Soho, negotiations had to be suspended for a day, as the men were all drunk. Carron suffered similarly, and Kelsall, in Wales, found some of his iron workers in 1729 off work, ' committed to the stocks for being drunk and abusive '. Wedgwood was much troubled by it, and so were the Manchester mill-owners, as is evident from Robert Owen's well-known account of his interview with Drinkwater.5 Later, indeed, it was claimed that Manchester mill

1 This is treated at greater length in my forthcoming paper on' Factory Discipline in the Industrial Revolution'. 2 T. C. Barker and J. R. Harris, A MerseyTownin the Industrial Revolution: St. Helens 17Jo-900o (Liverpool, I954), p. II6 ; A. Raistrick, 'The London Lead Company, I692-I905 ', Trans. Newc. Soc. xiv (I933-4), I56. 3 Josiah Wedgwood, Letters to Bentley,I771-I780 (Priv. circ. I903), p. I3I, 6 Feb. 1773. 4 Owen, Threading My Way, pp. 70, 72; A. Raistrick, Quakersin Scienceand Industry pp. 31, 78 ; 'London Lead Company ', pp. 36, I57; (I950), p. 174; Two Centuries, Ure, op. cit. p. 355. 5 Roll, op. cit. pp. 6i, 64; A. E. Musson and Eric Robinson,' The Early Growth of Steam Power', Econ. Hist. Rev. (2nd ser.), xi (I959), 434 ; Birmingham Assay Office, & Watt Correspondence, Boulton Watt to Boulton, 4 Oct. I779, 4 Oct. 1781, I March 1788,

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I964

IN

THE INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

523

workers were healthier and better workers than men in other occupations, as the factory left them no time for drink and debauchery.1 The community builder could do more than punish the offenders: he could restrict the sale of liquor. Owen made it a monopoly of his own shop, entered all purchases of liquor in a book, and used the profits to pay for his school; neither Deanston nor Blantyre permitted any public house to open in their villages.2 Lord Penrhyn, also, enforced the same ban in his model village. In 1831, J. J. Guest re-affirmed that no one in his employ would be allowed to keep a public house or a beershop,3 but the reasons for this were not merely those of keeping the workforce sober and industrious: they were largely concerned with the prevention of truck. VI The facts about the truck system in the company towns are well known. In our present context, however, they require a new interpretation : for truck shops were not only, like workers' cottages, sources of welcome petty profiteering : they also added yet further to the sheer burdens of management. Not all company shops were predatory. Clearly, the occasional purchase of grain wholesale, to be sold at cost price or less in times of harvest failure was to benefit the company only in as far as it benefited the workers, and such deliveries are known to have been made by Coalbrookdale, the Quaker Lead Co., David Dale, the Anglesea mines, the Lambton collieries, the Whitehaven collieries, the Tehidy estate, Tredegar and Sir Watkin Wynne's collieries. Further, from the early examples of the Elizabethan copper mines onwards, and in mines in the early seventeenth century, when it was, recognized that in isolated areas a manager, to start up, would need 'meate, drinke and rayment, sufficient to suffice them; also coyne and money for such workmen, to provide for themselves ',4 community builders have been forced, at times, to look after the food supply.5

26 Jan. 1789, 25 or 26 Sept. I786 ; Kelsall MSS. (Friend's House, London), v, 22 May Urwick and Brech, pp. 44 ff.; Campbell, CarronCompany, I729; pp. 52, 70; A. Birch, 'The Haigh Ironworks, I789-I856 ', Bulletinof the John Ryland'sLibrary, xxxv (i953), on the Woollen 33 ; Committee Manufacture of England,Parl. Papers 806, iii. 77; V. W. Bladen, ' The Potteries in the Industrial Revolution ', Economic History, i (I926), I30. 1 Lords' Committee on Apprentices,pp. 8, 24. 2 SelectCommittee on Childrenin Manufactories, P.P. I8i6, iii, pp. I64, I67, i68, I77; FactoriesCommission, Revolution in Supplementary Report, II; A. H. Dodd, TheIndustrial North Wales(Cardiff, 1933), p. 206. 3 Elsas, op. cit. p. 79. 4 Stephen Atkinson, The Discoverieand Historie of the Gold Mynes in Scotland(I6I9, repr. Edinburgh, I825) ; W. G. Collingwood, ElizabethanKeswick(Cumberland and Westmorl. and Antiqu. and Archaeol. Soc. Tract Series, viii, Kendal, I9I2), p. 7. 5 Bouch and Jones, op. cit. pp. 227-8 ; G. G. Hopkinson, The Development of Lead in North Derbyshire Mining,andof theCoalandIronIndustries andSouthYorkshire, 7 oo-i 8 o (Ph.D. Thesis, Sheffield, I958), p. 362; Fitton and Wadsworth, pp. 249-50; Cole, RobertOwen, pp. 68, 77; TwoCenturies, pp. 24, 40; Collier,' Early Factory Community', First Report, C. I, pp. II4-15; pp. 118-21 ; FactoriesCommission, Collier, Family Economy, p. 121 ; S.C. on Paymentof Wages,P.P. I842, QQ. 2995-7.

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

524

THE FACTORY

VILLAGE

July

Truck shops, profitable or not, were yet another burden on the limited managerial capacity available. They created permanent ill-will, disputes and occasional riots, such as those caused by the truck shops at Dowlais and Penydarren in 80o.1 Of the notorious shop at Dowlais, opened in i800, the senior partner wrote in 1803 : 'Tis a pity that our shopkeeping has been so very much less profitable than our neighbours. Mr. Lewis and myself have made up our minds that we will not have anything to do with shopkeeping other than receiving a good rent for it.' Hence it was let, but the tenant, despite the trouble taken to suppress competition for his sake, had paid neither rent or interest on the stock advanced after five years, and had to be sold up. A manager was then put in, and was paid a salary plus a share of the profits, but there were further difficulties. At neighbouring Cyfarthfa, likewise, William Crawshay ordered 'I must desire that neither Butter, Cheese, Flour, Tallow or aught else may be bo't for money', as it locked up his precious capital.2 Deductions from wages for tools, etc., could also be most troublesome to the limited clerical and managerial staff available. Thus the Mona Mine Co. had to deduct, at each pay day (once every two months) separate items for powder, candles, German steel, blister steel, waste of iron, shovels, mats, copper wire, smiths' cost, carpenters' bill, drawing, week's club, cartage and sieve rims : and of the oo payments due on 3I December 825 for example, only 39 had credit balances left, the rest were in debt which had to be carried over to the next period.3 Also, it should not be forgotten that competitors who did not engage in truck got away with paying lower wages, and that indebtedness worked both ways: while it tied the worker to his master, it also, in effect, forced the firm to continue to employ the worker.4 The link with the truck shop was often the substitute of shop notes for cash in wage payments. This was another expedient which could be turned to good account, as Samuel Oldknow found,5

p. 95 ; Elsas, op. cit. p. 36. Also Dodd, loc. cit. p. 405 ; Charles Hadfield, British Canals (I950), p. 37; SelectCommittee on ArtiZans and Machinery, Parliamentary Papers, I824, v, pp. 6II-I3. 2 Cyfarthfa MSS., i, 30 Nov. I8I5, 17 Jan., 5 April I8I6 ; Dowlais Letters (MSS., Glamorgan County Record Office), 27 Sep. i8oo, 26 July, 28 July I803, 2 Oct. 18I2. 3 Mona Mine MSS., Nos. 80, 2648. 4 For Crawshay, see the revealing letter in Mechanics' Magazine,24 Sep. 1831 ; also John P. Addis, The CrawshayDynasty (Cardiff, 1957), p. 4 ; Davies, op. cit. p. 138; Wilkins, Iron Trade,pp. 97-98 ; H. M. Cadell, TheRocksof WestLothian(1925), p. 330 ; Henry Hamilton, The English Brass and CopperIndustriesto I8oo (I926), pp. 316-17; Campbell, CarronCompany, p. 231 ; Quaker Lead Company, Minute Book (MS., North of England Institute, Newcastle), Regulation adopted io Sep. I784 ; Cyfarthfa MSS., Box II, I5 Dec. I830 ; G. W. Hilton, 'The British Truck System in the Nineteenth lxv (I957), pp. 253-4; S.C. on Manufactures, ev. Century ', Journalof Political Economy, Wm. Matthews, QQ. 9893,9899. 5 Geo. Unwin et al., SamuelOldknow andtheArkwrights(Manchester, I924), chapter I2. 1 D. J. Davies, The Economic History of South Wales Prior to 18oo (Cardiff, 1933), p. I38 ; John Lloyd, TheEarly Historyof theOld South WalesIronworks (I76o- 840) (I906),

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IN THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION 525 I964 but it was not an unmixedblessing, and could be more trouble than it was worth: ' Issue no more PromissoryNotes under ?ioo at any date whatever,' orderedWilliam Crawshay in 1816. 'It is not anyissue small to honourable and Notes,'-nor do they way respectable cause. for trouble the Similarly,his neighbour compensate they Taitt assertedin 1813 : 'We are not Bankersand do not wish to extend our circulationbeyond our own payments,'andhe noted with never stayed glee that Anthony Hill's notes in adjacentPenydarren out for more than ?I,ooo at a time. The work involved was,indeed, considerable. The Cyfarthfabalance sheet for i813 noted over C7,300outstandingon the ?i, i guineaand C5note account; while the printer's bill for Dowlais on 9 February 1822 included the following notes:

5,500 at ?' 5,000 ?I Is. od. 3,000 ?i Ios.od.

2,000

s5Os.

?IO

od.

500

besides 770 bills of exchange.l VII The large-scaleentrepreneurs of the day were dealing with such of unprecedented problems technology, marketingandlabourdiscipline and training,thatthey could have little initiativeleftfororiginating and putting into practiceany coherentsocial philosophy of their own. Rather,anysocialpoliciesadoptedwerethe resultof beingdriven from expedientto expedient,andfromcrisis tocrisis. Yet someentreand their were aware that they were buildpreneurs, contemporaries, communities2 an of some and of the socio-ethical had ing inkling problemsinvolved, and they were articulate enough to expressthem. How did they view their role in history? The large majoritybegan with the unspokenassumptionthat the works andthe profit-making drivebehindit providedtheir own justification,3and that the attached townships were appendagesto be judged only as such. By the sametoken, the workersand theirfamilies were, initially, viewed as pliable materialin the hands of the employer, 'hands' without brains, Pavlovian dogs without initiative or discrimination. Robert Owen was forced to appeal to his fellow employersto look after their labour by drawing the parallel of the carewith which they looked aftertheir machinery-an appeal to consider workers' lives as ends in themselves would not have found much sympatheticunderstanding.

1 Cyfarthfa MSS., i, 13 Jan., 17 Jan. I8I6, Box I2, Balance Sheet for I8I3 ; Dowlais Letters, 22 Jan. I8I3, 9 Feb. 1822. 2 D. F. MacDonald, op. cit. p. 6 ; Samuel Greg, TwoLetters to LeonardHorner,Esq.

(1840).

8 Lord, Capital and Steam Power,p. 226;

P. Garb, op. cit. p. 38.

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

526

THE FACTORY

VILLAGE

July

These views could be found at their crudest where the entrepreneurdominated local society in the absenceof the landed upper class, as in West Cumberland,or South Wales.' Thus the police power in MerthyrTydfilwas merelyan extension of the ironmasters' own long arms. In 1799, brandy dealersand trade unionists alike were dealtwith by Homfrayor Crawshay, the two ironmaster-magistrates.2 Therewas no doubt as to the outcome of the hearings,nor were the magistrates accusedof impartiality. In 1793, Homfrayhad to 'never sign a licence for any Workmanbelonging to promised the Ironworkswithout an applicationbeing madeby their Masters', while in I799, workmen who withdrew from the Volunteers were punished by being summarilydismissed by Guest. Twenty years later, travelling troupes of actors still found it necessaryto ask the employers'permissionbefore opening in Merthyr. Small wonder, that William CrawshaySr. bitterly opposed the notion of a resident magistratefor the town in i828 : 'You resident Ironmasterssh'd be the Justices and keep the Power in your hands, your stipendiary man may turn againstyou, ... it would not at all surprizeme when once seated in Place he would annoy instead of serve the Iron masters ....' However, he need not have worried : Mr. Bruce,the man chosen, was a ' most proper Gentleman'.3 In Whitehaven,again, the Lowthers were kings. The first earl of Lonsdale, losing a case over subsidencein I791, simply decided to close all the town's collieries,and was only persuadedto re-open them, on a guaranteeof indemnity in future cases, by 2,560 petitioners. His manager, John Bateman,found the local coroner in hadthought the stipendiary, as he had 1803as dangerousas Crawshay daredto hold an inquest on a woman killed in a mine accident.

only calculated to frighten the ignorant and discourage them from going into the Pits; on this account the workmen were alwaysforbid to even talk about any accidents which happened in the Pits ; your Lordship can judge better than me how far it may be proper to check

this new Practice.4 ... a thingneverpracticed herein my memory, such enquiry being supposed

Colliers lived in isolated and easily tyrannized communities,5 but textile manufacturers also cherished the power which the factory towns gave them. Richard Arkwright, Jr., reflected that in a large town he could not have the control over his workers which he had in Cromford, and G. A. Lee allowed that village mill owners ' command the population, and those who live in manufacturing

1 A. H. John, op. cit. pp. 68-69 ; Addis, op. cit. p. I4. Elsas, op. cit. I7 Jan., 3 Feb. 1799. 3Dowlais Letters, i8 Sep. 1793, 25 Apr. 1799, 4 Sep. x8i6, 9 June I8I8, 1820 ; Cyfarthfa MSS., Box ii, 19 Jan. i828, 19 Feb. I829.

2

I5

Sep. p.

5 Robert Bald, A General View the Coal Trade Scotland of of (Edinburgh, 72 ; Society for Betteringthe Condition of the Poor, 4th Report, pp. 240-1.

4 0.

Wood, op. cit. pp. 2I, I20o-.

I82),

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I964

IN THE INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

527

towns are in some degree commanded by the customs of the population '.1 The extent of that control may be illustrated by Catrine, a

typical cotton village : of a population of 2,7I6 in 1832, 1,304 were

women and children at home, 853 worked in the Company Mills, 759 worked elsewhere, but of these 194 were employed in ancillary

textile occupations. The proportions were similar in 1817 and 1819.2

Thus well over half of the earnings of the village came directly from the mill. In some villages, as in New Lanark, the proportion approached ioo per cent. To this power of the employer was added the power of the village master. Housing, for example, was not only a social service, or useful for attracting labour : it was also a source of profit, and a powerful weapon, often used cruelly, against trade unions and working class protests. The Herculaneum pottery, in I807, found not only that its cottage property yielded io per cent, but also that' the workmen ... are thereby become Domestics and the benefit and continuance of their labours with much greater certainty insured to the

Proprietors

'.3

Again, education, both religious and secular, was not simply philanthropic. Hannah More was concerned in her Mendip schools, 'to train up the lower classes to habits of industry and virtue ',4 and to religious beliefs which, in turn, were quietist.6 The Belper schools were praised as combating 'immorality and vice', but they also trained the men to abhor Luddism and trade unionism: 'they mostly understand that the masters' interest is their own.' The Quaker Lead Company's schools, so the manager declared, were responsible for the absence of Chartism, Radicalism ' and every other abomination ' from the villages. The early Mechanics' Institutes were often expected to make the lower classes more amenable and teach them ' respect for property '.6

'Factory Community', p. 117 ; Gorb, op. cit. pp. 136, I38; Collier, Family Economy, p. 125 ; S.C. on Childrenin Manufactories, pp. 279, 357. 2Factories Commission,Suppl. Report I, P.P. I834, xix, A. I, pp. 85-86; Lords' Evidence on theFactoryBill, Parl. Papers, 1818, xcvi, 66 ; Lords' Committee Committee, on Apprentices, Appx. 24; Ure, op. cit. p. 414. 3 Herculaneum Pottery, MinuteBook, fo. I 9; Gaskell, op. cit. p. 352; Fitton and Wadsworth, p. I04; Wilkins, op. cit. p. 149; TwoCenturies, pp. 30-31 ; J. E. Cule, op. cit. p. I91 ; Holland, Coal Trade,p. 293 ; Wentworth Woodhouse Muniments, St. 6 (vi) 9 Apr. I8oo; 0. Wood, op. cit. pp. 43, I46; Campbell, CarronCo. p. 69; Collier, Family Economy, p. io8 ; Lindsay, op. cit. pp. 278, 295. 4 M. G. Jones, The CharitySchoolMovement (Cambridge, I938), pp. 158-9. 6 A. E Dobbs, Education and SocialMovement o (1919), p. 140; Committee on I7o o-i theLabourof Children in Mills andFactories,Parl. Papers, I831 -2, xv, ev. Thomas Daniel; A. P. Wadsworth, 'The First Manchester Sunday Schools' Bull. John RylandsLibr. xxxiii (I951), 290-300 ; Hill, op. cit. p. 134 ; Smelser, op. cit. pp. 72-76. The early ' Ragged Schools' were similarly inspired, C. A. Bennett, Historyof ManualandIndustrial Educationup to 870o(Peoria, Ill. 1926), p. 223. 6 Fitton and Wadsworth, p. 103 ; Two Centuries, pp. 63 ff.; Mabel Tylecote, Mechanics Institutesof Lancashire and Yorkshire beforeI8,I (Manchester, 195 ), pp. 44-49. 1 Collier,

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

528

THE FACTORY

VILLAGE

July

Henry Ashworth, a noted philanthropist community builder (who incidentally made the children pay for their own education) would 'always prefer a child who has been educated at an infant school, as those children are most obedient and docile'. If educated, it was widely recognized, they would be more valuable workers, and training by the employer would end apprenticeship and unionism in skilled trades.' Just as education could be viewed as merely an expedient 'to turn workers into a reliable factor of production ', so ulterior motives could be found for sick clubs, which were in part established to lower the poor rates as by Boulton and by Wilkinson, or to undermine unionism, as in the coal mines. Carron Company indeed decided in 770 that it was 'a bad practice to support the colliers when sick-for while they find we do so they will take the less care of themselves '.2 While trying to reduce drunkenness, one employer admitted having refused a man a licence for a very different reason, for 'I am certain if he keeps an Alehouse you will loose him as a Workman '.3 Nothing strikes so modem a note in the social provisions of the factory villages as the attempts to provide continuous employment. 'There are two objects you wish to gain,' Treweek, the Mona Mine manager wrote to Sanderson, Lord Uxbridge's agent, 'the first is to make the Mine yield a profit, the second is if possible to employ all the men', and he went to great trouble to find them employment.4 Similarly, William Crawshay commanded in I817, 'Do not even hold out reduction of the men, employ them if they behave quietly... Bad and ruinous as the trade now is, we must lose rather than starve the labourer.'5 Yet, of these two places, Cyfarthfa was noted for its persecution of unionists, and at Amlwch, in I813, it was reported that with the decline in employment, 'many families have fled, and their cottages are now falling to ruin, but there is still a much more numerous population than can be tolerably supported by the mines, and numbers are consequently left in a miserable state of destitution '.6 While some employers paraded their social conscience in finding continuous employment for members of their workers' families, it is clear from the example of Samuel Oldknow that this was a necessity, for otherwise the families could not have been kept

1 FactoriesCommission, First Report, E. p. 5, Second Report, E. p. 2 ; Two Centuries, p. 72 ; Hill, op. cii. pp. x30,I36; D. C. Coleman, TheBritishPaperIndustry149y-I86o

(1958), p. 236.

2

Roll, op. cit. p. 226; Holland, Coal Trade,p. 301 ; Campbell, CarronCo., p. 67. 3 Dowlais Letters, Homfray to Thompson, 18 Sep. I793. 4 Mona Mine MSS., No. 2553, 5 May I827, also Nos 205, 1048, 1374 ; Rowlands, op. cit. pp. 256, 269 ; Dodd, op. cit. p. I6o. 5 Cyfarthfa MSS., 5 Feb. I8I7, also I5 June, 30 Aug. I820, I3 Jan. I822, Box ii, 22 May, x6 Nov. I830. 6 Richard Ayton, A VoyageRoundGreatBritain (8 I 5), ii. II.

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IN THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION 529 I964 alive on the starvationwage paidby the mill to women and children.1 Further,while even mediocre employers went to much trouble to pay their workers on Fridays or early on Saturdaysto get the advantage of a Saturdaymarket,2the senior partnerin a respectable firmlike the Dowlais Iron Co. could callouslyadvocate' that we pay our men only once a month in future which will save us 3 broken days in the month besides those drunkencombinations'.3 Conversely, truck payments could be advocated, and perhaps introduced,with the highest motives: they were alleged to have as their objects the reductionin drunkenness,the benefit of the shopping housewife, and compulsorysaving for largeritems of expenditure4; while miners were overchargedfor candles, etc., in order, it was said, to reduce pilfering.5

VIII This paperhas attemptedto establishtwo propositions. The first is that the pressure on the managerialand innovating energy and ability of factory village owners was very great by any standards, and has often been underrated. The second is that this pressure the natureof their ' social' policies. Community largelydetermined before builders, I830, did not start with a social ideal.6 Robert Owen's plans arose out of his experienceand expedients, at New Lanark, and in Manchester,and Samuel Greg did not begin at Bollington until I832 after years of experience in other mills. There is no reason to assume that WalterEvans, of Darley Abbey, for example,was anythingbut a pragmatist,or that the QuakerLead Companywas looking for 'paternal responsibility' before circumstancesmadeit imperative.7 SamuelOldknow'sbiographers, indeed claim that he was driven by' ambitionto control and direct the life

1 SamuelOldknow, pp. I66-8; for Arkwright's similar motivation, see Fitton and Wadsworth, p. 104. 2 First Report, C. I, p. 38, B. I, p. 8I, E. Kilbur Scott E.g. FactoriesCommission, (ed.), Matthew Murray, PioneerEngineer,Records for 176y-1826 (Leeds, I928), p. 4; Wentworth Woodhouse Muniments, A. 1389, Instruction Book, paras. 8, 3x. 8 Elsas, op. cit. p. 34, I7 Jan. I799. 4 G. W. Hilton,' The Truck Act of I831 ', Econ. Hist. Rev. (2nd ser.), x (I958), 470; L. T. C. Rolt, ThomasTelford(I958), p. 8i ; F. Collier, ' Workers in a Lancashire Factory at the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century ', Manchester School,vii (I936), 52 ; Soc. for Betteringthe Conditionof the Poor, 4th Report, pp. 238-9 ; Sir Noel CurtisBennett, TheFood of the People(949), p. 101 ; Malet, op. cit. p. I74; S.C. on Paymentof p. 42. Wages,Q. 3032; Collier, Family Economy, 5 Titley, op. cit. p. 33; Mona Mine MSS., No. 2633, quoting letter 2 Dec. 1819. 6 Samuel Greg, op. cit. and Collier, Family Economy. Prof. Ashworth could find only two planned townships before 1830, and one of these is doubtful. W. Ashworth, 'British Industrial Villages in the x9th Century', Ec. Hist. Rev. (2nd ser.), iii (I951). 7 Sir Richard the UnitedKingdom Phillips, A PersonalTourThrough (1828), pp. I25-6; Lindsay, op. cit. p. 278 ; TwoCenturies, p. 5.

VOL. LXXIX-NO. CCCXII

LL

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

530

THE

FACTORY

VILLAGE

July

of a community ', or to 'found a community', even though this created financial difficulties for him, but there is no evidence whatever to support this view : all the records, on the contrary, point to a simple decision to establish a cotton mill on a village site, with only a belated recognition of the community needs involved.1 In the absence of any coherent or commonly accepted social doctrine, other than perhaps the irrelevant belief in laissez-faire,interpreted in the light of narrow self-interest, each entrepreneur, when faced with the pressure of rapid decision making, was bound to draw on the deeper resources of his character to solve each immediate crisis. Thus Quakers showed some fine feeling for their workers, but made high demands of moral conformity on them; truly Christian masters, like Owen or the Fieldens, attempted to humanize not only their works, but also those of others ; and the hypocrites employed clergymen, sometimes paid with the workers' pence, to teach their hands how to suffer starvation wages without protest. Some masters, with very little cause, boasted of their humanity, and found sycophants to spread their fame, while others, quietly, set themselves very much higher standards of responsibility. Apart from the general agreement on the overriding primacy of profits over the interests of the village workers, there was no common standard of values to which to appeal. But further, no matter how detached the community builder was from his workers as persons, and how crude his notion of worker psychology and motivation, the very fact of having to cater for their needs forced on him some modicum of understanding of the humanity of his ' hands '. It has often been remarked that the close personal touch of the early industrial employer did not prevent him from imposing vicious conditions on his workers and leaving them paupers when they were no longer useful 2; yet others provided playgrounds in their villages, musical instruction and instruments, libraries and such amenities as cooking and washing facilities, heating or a cafeteria in the works, without being driven to them by legislation or the healthy example of others. Labour shortages, fears of riots and epidemics, and other emergencies were not continuous, but every such occurrence left a residue of more humane outlook on the average employer, just as the recent period of full employment has led many employers to the reflection that high wages and good conditions are necessary, not because of economic pressures, but

1 SamuelOldknow,pp. I35, I75. Nor is there any evidence that he was anything but a mediocre businessman, who never understood the reason for his windfall profits in the seventeen-eighties and his bankruptcy in the seventeen-nineties. He was merely fortunate in his biographers. The Moravians alone, at Dukinfield and later Fairfield, thought of the community first, but they did not run a modern factory. J. Aikin, A Descriptionof the Country from Thirty to Forty Miles roundManchester (I795), pp. 232-3, Below,pp. 47-57. 454; Armytage, Heavens 2 E.g. Urwick and Brech, op. cit. pp. 8-9.

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1964

IN THE

INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

5 31

because of their common humanity. In the industrial revolution the change of heart took a long time, perhapsfar too long; but by the eighteen-thirties, when FactoryActs and other legislation began to reducethe freedom of the village master,he was halfwayto being convinced that to treat his labour factor of production more kindly might make it more profitablealso.

Universityof Shefield

SIDNEY POLLARD

This content downloaded from 158.227.185.87 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 13:24:13 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1091)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Course For Loco Inspector Initial (Diesel)Documento239 pagineCourse For Loco Inspector Initial (Diesel)Hanuma Reddy93% (14)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Nptel Transmission Tower Design Lecture 2Documento33 pagineNptel Transmission Tower Design Lecture 2Oza PartheshNessuna valutazione finora

- 20005-03 B8rle Eu6 X900 D8KDocumento217 pagine20005-03 B8rle Eu6 X900 D8KGuillermo Guardia Guzman100% (1)

- Tedds Engineering Library (GB)Documento125 pagineTedds Engineering Library (GB)Mohd Faizal100% (1)

- Railway - Points - Crossings - 2015Documento54 pagineRailway - Points - Crossings - 2015Poomagan94% (16)

- Welding Technology - NPTELDocumento145 pagineWelding Technology - NPTELpothirajkalyan100% (1)

- Relay MBCZDocumento70 pagineRelay MBCZMohsin Ejaz100% (1)

- Actions On Structures: SIA 261:2003 Civil EngineeringDocumento6 pagineActions On Structures: SIA 261:2003 Civil EngineeringEliza BulimarNessuna valutazione finora

- Stray Currents Mitigation, Control and Monitoring in Bangalore Metro DC Transit SystemDocumento7 pagineStray Currents Mitigation, Control and Monitoring in Bangalore Metro DC Transit SystemAnil Yadav100% (1)

- 2012 Nacto Urban Street Design GuideDocumento37 pagine2012 Nacto Urban Street Design Guidearkirovic1994100% (2)

- Amazon On The T Somerville Ma DigitalDocumento81 pagineAmazon On The T Somerville Ma DigitalAlex NewmanNessuna valutazione finora

- GO No-86Documento40 pagineGO No-86Perez Zion100% (1)

- Station Platform Design Requirements: Issue:1 Revision: ADocumento18 pagineStation Platform Design Requirements: Issue:1 Revision: AAndy AniketNessuna valutazione finora

- Mumbai MetroDocumento3 pagineMumbai MetroNila VeerapathiranNessuna valutazione finora

- Nice - Practical Guide (2004)Documento44 pagineNice - Practical Guide (2004)afrancesadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Anand Vihar Rrts Station: Cut and CoverDocumento1 paginaAnand Vihar Rrts Station: Cut and CoverAnonymous USbc7XzsA6Nessuna valutazione finora

- DLT Entities 11-01-2024Documento21 pagineDLT Entities 11-01-2024nitish.jhaNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 July - 31 Aug 2018: The Education University of Hong Kong School Bus Service During The Summer BreakDocumento2 pagine3 July - 31 Aug 2018: The Education University of Hong Kong School Bus Service During The Summer BreakTak On SzeNessuna valutazione finora

- FEB Leasing and Finance Corp vs. Spouses Baylon Et - Al. GR No. 181398, June 29, 2011 FactsDocumento4 pagineFEB Leasing and Finance Corp vs. Spouses Baylon Et - Al. GR No. 181398, June 29, 2011 FactsJoseph MacalintalNessuna valutazione finora

- Lotte Shopping MallDocumento41 pagineLotte Shopping Mallmyusuf123Nessuna valutazione finora

- ORDENANZA #2348-2021 - Norma Legal Diario Oficial El PeruanoDocumento28 pagineORDENANZA #2348-2021 - Norma Legal Diario Oficial El PeruanoGustavo Carhuamaca RoblesNessuna valutazione finora

- Difference Between Icf and LHB BogiesDocumento3 pagineDifference Between Icf and LHB BogiesVijay AnandNessuna valutazione finora

- El Paso Scene September 2018Documento40 pagineEl Paso Scene September 2018Anonymous gMmJrV1pfNessuna valutazione finora

- Question AnswerDocumento141 pagineQuestion AnswerSiddharth PradhanNessuna valutazione finora

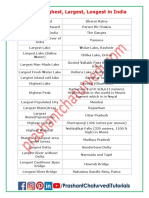

- Biggest Highest Largest Longest in IndiaDocumento4 pagineBiggest Highest Largest Longest in IndiaSaikumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Inventive Pricing of Urban Public TransportDocumento19 pagineInventive Pricing of Urban Public TransportSean100% (1)

- Welcome To Indian Railway Passenger Reservation EnquiryDocumento1 paginaWelcome To Indian Railway Passenger Reservation EnquiryAbhishek GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ertms Dmi DocumentDocumento113 pagineErtms Dmi DocumentGoutam BiswasNessuna valutazione finora

- Cargo Securing in ContainersDocumento4 pagineCargo Securing in ContainersFatihah YusofNessuna valutazione finora

- East Harlem Proposed Rezoning PlanDocumento40 pagineEast Harlem Proposed Rezoning PlanDNAinfoNewYorkNessuna valutazione finora