Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

GEND3031 Individual Assignment 1 809000325 de Freitas - Burning Fields: Education As Resistance

Caricato da

Karyn De FreitasTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

GEND3031 Individual Assignment 1 809000325 de Freitas - Burning Fields: Education As Resistance

Caricato da

Karyn De FreitasCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Student Name: Karyn De Freitas Student ID: 809000325 Course: GEND3031- Sex, Gender, and Society Title: Burning

schools- Education as Resistance

The schools are your only chance. - School principal, Sarafina!

The film Sarafina the musical of the same name which was written by Mbongeni Ngema. Ngemas musical tells the story of the Soweto Riots which began in 1976. These riots began as a reaction to a decree that mandated teaching in all-black schools to be done in Afrikaans and English. Increasing resentment towards a weakening apartheid meant that students were not as accepting of the decree. The resulting riots led to the deaths of more than 180 students and countless injuries. The film captures the story very well as it follows Sarafina, the protagonist. Apart from the artistic rendering of historical events, the film raises questions about the nature of oppression, struggles for freedom, and gender roles. In the movie, many social institutions are depicted, the church, the family, the community, the police, education, the economy, the military. Those who fought for freedom and the abolition of apartheid were often faced with aggressions from many of these social institutions within South African society. Insitutions such as the military, the police, were forceful antagonists, while insitutions such as the family, the church, and education were more equivocal. This equivocality often left room

for various forms of resistance. In Sarafina!education is seen as having a dual nature: it can either maintain or resist oppressions. Education, as a social institution, is often the most open to change and revolution. According to Verwiebe, a social institution is a system of behavioral and relationship patterns that are densely interwoven and enduring, and function across an entire society. [] Institutions regulate the behavior of individuals in core areas of society. Education is considered a social institution because it satisfies the criteria stated above and it is a primary source of socialisation. Outside of the family, the school is one of the main places where children will learn socially acceptable behaviours and attitudes from their peers and educators. Education, as an institution, is responsible for how people think and how they interact with the world. It informs societies on many other social institutions. It is within the institution of education that ideas about gender roles, race, and sexuality are developed and reinforced. Education can decide ones future identit y and social status. As an institution, education is highly powerful. It is filled with the potential of open and inviting unshaped minds. It is no surprise, then, that education is often the epicentre of a great battle between freedom and oppression. Education is responsible for how societies think; future generations depend on what is taught to current generations. As such, the duration of ones education and the extent of ones knowledge holds a great deal of weight in society. Highly educated people are often placed on pedestals as beacons of progress, less educated people are ridiculed for not achieving those standards. For as long as education has been a social institution, various agents have sought to harness its vast potential. Many resistance movements began in educational institutions. Many governments were able to control their populations through censorship, propaganda and tightly controlled syllabi. Within the historical context of the film, students led riots about the way in which they were going to be taught. They viewed it as an attempt by the government to directly control the way they related to their peers, their communities, and the whites of South Africa. Their attitudes had been informed by Black Power movements in the United States,

and when the decree was made, they were able to speak and act out against it. This highlights a crucial aspect of education as an institution that is often undervalued: education is highly self-critical and selfaware, moreso than other institutions. This self-awareness and ability to be critical of itself as an institution contributes to the dual nature of education. In Sarafina!it becomes evident that there are two opposing symbols of education: the school principal, who can be viewed as a symbol of education as a means of maintaining the status quo, and Mary Masombuka, who can be viewed as education as a means of resistance and revolution. Throughout the movie, the principal is portrayed as collaborating with the police and the military. He pleads with Mary Masombuka to follow the syllabus and teach the children what has been deemed as necessary for their education. Mary Masombuka, on the other hand, teaches the children what she considers their history, she desires to know more about themselves than what the white government will have them know. The conflict between these two opposing ideologies is best portrayed in the classes on the Napoleonic War: Mary Masombuka teaches the children that it is the people of Moscow who defeated the French by burning the city, while the substitute teacher teaches a more apathetic slant. The children, realising this difference, rebel and scare the teacher out of the class. This image of students as agents of resistance is one that is recurrent in various societies. From student protestors in Ukraine today, to student protestors against the Vietnam War, to student protestors against the destruction of the Creative Arts Centre at the St. Augustine campus of the University of the West Indies, and to the students in Sarafina! who protested about a decree that sought to separate them from their community, students have often been revolutionaries and visionaries. It is difficult to identify why students are so often catalysts and agents of change. Perhaps it is their youth, perhaps it is the process of education that often renders one more open-minded than when one began the process, but students can often make or break the struggle against oppression. The difficulty lies in their sympathy to ones cause. They are well-aware of what those older than them

think and feel, but they are also in the process of making their own judgements. Often, students take a more humanist and liberal view, and, without the influence of government propaganda, they often take the sides of anti-government forces. An example of these divergent views can be seen in how the school principal and Sarafina both react to the burning of the school. The school principal, who views teaching as his vocation and a means of social mobility, says The schools are your only chance. and Burn the schools and you have no future.On the other hand, Sarafina, while she acknowledges that burning schools are not necessarily beneficial, she understands the need for action instead of passive inaction. She participates in the execution of Sabela even though she views the use of fire as having no future. She expresses this before Sabelas execution when she says ...I like him. Except he burns down schools. Whats the future in that? Hell take me to the movies and then hell be in prison for 20 years. Sarafina sees a future in education, but she also sees a need for action. Her views, in this way, align with those of Mary Masombuka, who she looks up to. Mary Masombuka, is a highly influential character in the film: she helps the students realise that they have a part in history. She encourages them to look for themselves in history, to be able to plot the trajectories of their futures. Even her imprisonment and death motivate the students to take some sort of action. She encourages the students to question everything that they have been taught. She even encourages the students to question traditional gender roles. When Sarafina proposes a musical about Mandela being freed and asks to play the role, instead of rejecting the idea, Mary embraces it and encourages it. She does not want the students to limit their thinking about themselves and what they can do. In this way, Sarafina! is brilliantly intersectional in that it is able to touch on topics of race, power and gender at the same time. That the narrator of the story of the Soweto Riots is a young girl instead of a young boy, further serves to illustrate the feminist nature of the film. Sarafina! and other films of a similar bent, films that portray historical revolutions, especially revolutions carried out by People of Colour, often tackle several issues at once. The intersectional

nature of revolution should not be ignored, as oppression does not work alone a single plane, but along several axes. Persons who benefit from one from of oppression often utilise other forms of oppression to further their domination. It is for this reason that one should not separate struggles to further ones cause. The fight for ones oppression while oppressing others is a highly counterproductive and often destructive one. To quote Audre Lorde, There is no hierarchy of oppression. I cannot afford the luxury of fighting one form of oppression only. I cannot afford to believe that freedom from intolerance is the right of only one particular group. And I cannot afford to choose between the fronts upon which I must battle these forces of discrimination, .wherever they appear to destroy me. And when they appear to destroy me, it will not be long before they appear to destroy you.

Works Cited

Lorde, Audre. "There is no hierarchy of oppressions." Bulletin: Homophobia and Education 14.3/4 (1983): 9.

Verwiebe, Roland. Social Institutions Encyclopedia of Quality of Life Research. Ed. Alex Michalos. Dordrecht: Springer. 2014.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Freedom WritersDocumento3 pagineThe Freedom WritersKeshawn SutherlandNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Resistance: Radicals, Revolutionaries, and Cultural Subversives in the ClassroomDa EverandTeaching Resistance: Radicals, Revolutionaries, and Cultural Subversives in the ClassroomJohn MinkValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (2)

- Sdogra Curriculum Unit FrameworkDocumento7 pagineSdogra Curriculum Unit Frameworkapi-308654373Nessuna valutazione finora

- Week 3 Reading 2Documento38 pagineWeek 3 Reading 2Chloe FraserNessuna valutazione finora

- Student Power by Aaron KreiderDocumento15 pagineStudent Power by Aaron KreiderJohnPaoloBencitoNessuna valutazione finora

- Freedom Writers inspiring true story of a teacher changing livesDocumento2 pagineFreedom Writers inspiring true story of a teacher changing livesJude Vincent MacalosNessuna valutazione finora

- MALALADocumento1 paginaMALALARenelyn Rodrigo SugarolNessuna valutazione finora

- Samata Allen 1Documento8 pagineSamata Allen 1api-355912502Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ytell - Concentration Winter 2020Documento18 pagineYtell - Concentration Winter 2020api-555343739Nessuna valutazione finora

- Harrison-Chen-NegNewark Invitational 2022-Round1Documento15 pagineHarrison-Chen-NegNewark Invitational 2022-Round1Richard NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Peer Pressure EssaysDocumento6 paginePeer Pressure Essaysafhbfbeky100% (2)

- Why bsCEMDocumento3 pagineWhy bsCEMRavinder Singh BhullarNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminalization of Black Girls in SchoolsDocumento7 pagineCriminalization of Black Girls in SchoolsOlivia WilliamsNessuna valutazione finora

- Persepolis EssayDocumento11 paginePersepolis EssaySpam BertNessuna valutazione finora

- BoardhearingstatementDocumento2 pagineBoardhearingstatementapi-312068884Nessuna valutazione finora

- Same-Gender Education ResearchDocumento6 pagineSame-Gender Education Researchapi-300241546Nessuna valutazione finora

- Turn Up For Freedom: Notes for All the Tough Girls* Awakening to Their Collective PowerDa EverandTurn Up For Freedom: Notes for All the Tough Girls* Awakening to Their Collective PowerNessuna valutazione finora

- Line of Inquiry: What Literary Strategies Does Malala Yousafzai Use To Address The Subject ofDocumento5 pagineLine of Inquiry: What Literary Strategies Does Malala Yousafzai Use To Address The Subject ofAnupransh SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mosaic ProgramDocumento30 pagineMosaic Programcbao9161Nessuna valutazione finora

- Student Power Movement in the PhilippinesDocumento3 pagineStudent Power Movement in the PhilippinesaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lucy Licea - Persepolis CHDocumento2 pagineLucy Licea - Persepolis CHapi-520867331Nessuna valutazione finora

- Eng2603 - Assignment 1Documento7 pagineEng2603 - Assignment 1Kiana Reed100% (1)

- Martin Luther King Jr. - The Modern Negro Activist (1961)Documento4 pagineMartin Luther King Jr. - The Modern Negro Activist (1961)Vphiamer Ronoh Epaga AdisNessuna valutazione finora

- My Children My AfricaDocumento30 pagineMy Children My AfricaReham Mohamed88% (17)

- Te825 Criticalreflection Week3 AndersonDocumento5 pagineTe825 Criticalreflection Week3 Andersonapi-523371519Nessuna valutazione finora

- Co - EducatonDocumento2 pagineCo - EducatonaneebaNessuna valutazione finora

- Leaflet Anarchism and Youth Liberation SiversteinDocumento2 pagineLeaflet Anarchism and Youth Liberation SiversteinSteve HeppleNessuna valutazione finora

- Does Co-Education Disadvantage Female StudentsDocumento5 pagineDoes Co-Education Disadvantage Female StudentsTahir MehmoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis EssayDocumento6 pagineAnalysis EssayJonathan FranklinNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation 1Documento18 paginePresentation 1Mark Joseph MabugayNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay 1Documento5 pagineEssay 1api-271299430Nessuna valutazione finora

- Freire's Banking Concept of EducationDocumento2 pagineFreire's Banking Concept of EducationJasmineKylaNessuna valutazione finora

- FeminismDocumento17 pagineFeminismChaReignzt CatanyagNessuna valutazione finora

- Persepolis CHDocumento2 paginePersepolis CHapi-520774179Nessuna valutazione finora

- Running Head: Feminist Activism For Art Educators 1Documento14 pagineRunning Head: Feminist Activism For Art Educators 1api-340607582Nessuna valutazione finora

- Oppression Essay ThesisDocumento5 pagineOppression Essay Thesisreneewardowskisterlingheights100% (2)

- Pet Wakakakakakaka Samina Mina Eh EhDocumento12 paginePet Wakakakakakaka Samina Mina Eh EhSyafiq AddinNessuna valutazione finora

- Martinez, Aja Y. Writing SampleDocumento12 pagineMartinez, Aja Y. Writing Sampleaym4723Nessuna valutazione finora

- Multicultural Education Module 4Documento3 pagineMulticultural Education Module 4api-354531566Nessuna valutazione finora

- Final Paper - Lopez ContemporaryDocumento5 pagineFinal Paper - Lopez ContemporaryNica LopezNessuna valutazione finora

- English Synthesis EssayDocumento5 pagineEnglish Synthesis Essayapi-286654930Nessuna valutazione finora

- Positionality PaperDocumento5 paginePositionality Paperapi-309983610Nessuna valutazione finora

- Join Bscem: Inquilab Zindabad! Students Unity Long Live! Struggle Against All Oppressions and Exploitations!Documento4 pagineJoin Bscem: Inquilab Zindabad! Students Unity Long Live! Struggle Against All Oppressions and Exploitations!Ravinder Singh BhullarNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender For Students 2021 - 5Documento30 pagineGender For Students 2021 - 5LaaarNessuna valutazione finora

- WavesDocumento51 pagineWavesAman Ullah GondalNessuna valutazione finora

- The Ideology of "Fag"Documento10 pagineThe Ideology of "Fag"PersonmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal Reflections On Anti-Racism Education For A Global ContextDocumento12 paginePersonal Reflections On Anti-Racism Education For A Global ContextLois 223Nessuna valutazione finora

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion 1Documento15 pagineDiversity, Equity, and Inclusion 1api-378481314Nessuna valutazione finora

- Roger M. Villamar, PH.D.: Statement of Teaching PhilosophyDocumento2 pagineRoger M. Villamar, PH.D.: Statement of Teaching PhilosophyOpeningDoorsProjectNessuna valutazione finora

- Nyanhongothesis - Gender Oppression and Possibilities of Empowerment - Images ofDocumento177 pagineNyanhongothesis - Gender Oppression and Possibilities of Empowerment - Images ofJoana PupoNessuna valutazione finora

- Oppressed. Freire (1970) Defines Oppression As A Sort of Dehumanization, With The Oppressors BeingDocumento6 pagineOppressed. Freire (1970) Defines Oppression As A Sort of Dehumanization, With The Oppressors Beingapi-131948014Nessuna valutazione finora

- Final IO ScriptDocumento4 pagineFinal IO ScriptAmeya NaikNessuna valutazione finora

- Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in SchoolsDa EverandPushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in SchoolsValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (34)

- Christensen - Short PaperDocumento7 pagineChristensen - Short Paperapi-237535118Nessuna valutazione finora

- Partnership Education in The 21st Century: Riane EislerDocumento10 paginePartnership Education in The 21st Century: Riane Eislerskymate64Nessuna valutazione finora

- Edu 201 SandersjonahschoolingtheworldDocumento4 pagineEdu 201 Sandersjonahschoolingtheworldapi-735955672Nessuna valutazione finora

- Educational EssaysDocumento8 pagineEducational Essaysafibxprddfwfvp100% (2)

- Good Thesis Statements For Gender RolesDocumento6 pagineGood Thesis Statements For Gender Rolesgingermartinerie100% (2)

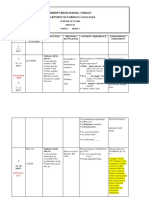

- SJS SOW 1ST Term 2018-19 CorrectedDocumento7 pagineSJS SOW 1ST Term 2018-19 CorrectedKaryn De FreitasNessuna valutazione finora

- FRENCH KD 2 Form 2 Term 1Documento6 pagineFRENCH KD 2 Form 2 Term 1Karyn De FreitasNessuna valutazione finora

- FRENCH KD 2 Form 2 Term 1Documento6 pagineFRENCH KD 2 Form 2 Term 1Karyn De FreitasNessuna valutazione finora

- Phonology Essay DraftDocumento1 paginaPhonology Essay DraftKaryn De FreitasNessuna valutazione finora

- De Freitas - EDRS5450 - Chapter 1Documento4 pagineDe Freitas - EDRS5450 - Chapter 1Karyn De FreitasNessuna valutazione finora

- All Works Cited and BibligraphyDocumento2 pagineAll Works Cited and BibligraphyKaryn De FreitasNessuna valutazione finora

- Sampson RacialEthnicDisparitiesDocumento66 pagineSampson RacialEthnicDisparitiesKaryn De FreitasNessuna valutazione finora

- Guayadeque User ManualDocumento31 pagineGuayadeque User Manualmist3rwalterNessuna valutazione finora

- De Freitas 809000325 GEND3039 Assignment 1Documento10 pagineDe Freitas 809000325 GEND3039 Assignment 1Karyn De FreitasNessuna valutazione finora

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Stat1342.001.09s Taught by Yuly Koshevnik (Yxk055000)Documento5 pagineUT Dallas Syllabus For Stat1342.001.09s Taught by Yuly Koshevnik (Yxk055000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNessuna valutazione finora

- Reading Practice Test 1 - IELTS Academic - Take IELTSDocumento2 pagineReading Practice Test 1 - IELTS Academic - Take IELTSM Teresa Leiva0% (1)

- Training Evaluation An Analysis of The Stakeholders' Evaluation Needs, 2011Documento26 pagineTraining Evaluation An Analysis of The Stakeholders' Evaluation Needs, 2011Fuaddillah Eko PrasetyoNessuna valutazione finora

- Recovering A Tradition Forgotten Women's VoicesDocumento5 pagineRecovering A Tradition Forgotten Women's VoicesAnik KarmakarNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning That Lasts - Webinar 01 PPT Slides (Survival Tips - Hints) TG 220420Documento12 pagineLearning That Lasts - Webinar 01 PPT Slides (Survival Tips - Hints) TG 220420Özlem AldemirNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical List For Regular 18-03-22Documento100 pagineMedical List For Regular 18-03-22FightAgainst CorruptionNessuna valutazione finora

- 1MS Sequence 02 All LessonsDocumento14 pagine1MS Sequence 02 All LessonsBiba DjefNessuna valutazione finora

- 11 11-11 19 11th Grade Garrison Lesson Plan Secondary TemplateDocumento2 pagine11 11-11 19 11th Grade Garrison Lesson Plan Secondary Templateapi-326290644Nessuna valutazione finora

- Akhilesh Hall Ticket PDFDocumento1 paginaAkhilesh Hall Ticket PDFNeemanthNessuna valutazione finora

- Chaudhury Et. Al. - 2006Documento30 pagineChaudhury Et. Al. - 2006L Laura Bernal HernándezNessuna valutazione finora

- Kierkegaard's 3 Stadia of Life's Way Guide to Resisting IndifferenceDocumento2 pagineKierkegaard's 3 Stadia of Life's Way Guide to Resisting IndifferenceJigs De GuzmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethnic and Cultural Identities Shape Politics in MoldovaDocumento25 pagineEthnic and Cultural Identities Shape Politics in MoldovaDrobot CristiNessuna valutazione finora

- Reductive Drawing Unit Plan 5 DaysDocumento31 pagineReductive Drawing Unit Plan 5 Daysapi-336855280Nessuna valutazione finora

- International BusinessDocumento5 pagineInternational BusinessKavya ArasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity Design Cambagahan Es Eosy RitesDocumento24 pagineActivity Design Cambagahan Es Eosy RitesNecain AldecoaNessuna valutazione finora

- Academic and Social Motivational Influences On StudentsDocumento1 paginaAcademic and Social Motivational Influences On StudentsAnujNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Lesson Plan For Catch Up FridayDocumento2 pagineSample Lesson Plan For Catch Up Fridayailynsebastian254Nessuna valutazione finora

- Prometric Electronic Examination Tutorial Demo: Click On The 'Next' Button To ContinueDocumento5 paginePrometric Electronic Examination Tutorial Demo: Click On The 'Next' Button To ContinueNaveed RazaqNessuna valutazione finora

- November 2019 Nursing Board Exam Results (I-QDocumento1 paginaNovember 2019 Nursing Board Exam Results (I-QAraw GabiNessuna valutazione finora

- Eamcet 2006 Engineering PaperDocumento14 pagineEamcet 2006 Engineering PaperandhracollegesNessuna valutazione finora

- 1st COT DLLDocumento4 pagine1st COT DLLCzarina Mendez- CarreonNessuna valutazione finora

- Iare TKM Lecture NotesDocumento106 pagineIare TKM Lecture Notestazebachew birkuNessuna valutazione finora

- ZumbroShopper13 10 02Documento12 pagineZumbroShopper13 10 02Kristina HicksNessuna valutazione finora

- Emerging-Distinguished Rubric for Art SkillsDocumento2 pagineEmerging-Distinguished Rubric for Art SkillsCarmela ParadelaNessuna valutazione finora

- California Institut For Human ScienceDocumento66 pagineCalifornia Institut For Human ScienceadymarocNessuna valutazione finora

- Scie6 - Q2 Module 2 - v3 1Documento49 pagineScie6 - Q2 Module 2 - v3 1great.joyboy8080Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dar Al-Handasah Final Report 03Documento38 pagineDar Al-Handasah Final Report 03Muhammad Kasheer100% (1)

- Tet Paper I Q-4Documento32 pagineTet Paper I Q-4mlanarayananvNessuna valutazione finora

- Practical Woodworking: Creativity Through Practical WoodworkDocumento23 paginePractical Woodworking: Creativity Through Practical WoodworkMaza LufiasNessuna valutazione finora