Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Beikler and Flemmig Proofs 2010

Caricato da

orthodontistinthemakingCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Beikler and Flemmig Proofs 2010

Caricato da

orthodontistinthemakingCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Periodontology 2000, Vol. 53, 2010, 118 Printed in Singapore.

All rights reserved

2010 John Wiley & Sons A/S

PERIODONTOLOGY 2000

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

Oral biolm-associated diseases: trends and implications for quality of life, systemic health and expenditures

T H O M A S B E I K L E R & T H O M A S F. F L E M M I G

Biolms are surface-associated communities of microorganisms embedded in an extracellular polymeric substance, which upon contact with the host may affect tissue hemostasis and result in disease (61). It is estimated that approximately 80% of the worlds microbial biomass resides in a biolm state and that microbial biolms cause more than 75% of all microbial infections found in humans (35). The oral cavity is replete with biolms colonizing mucous membranes, dental materials and teeth (57, 110, 120, 121, 123). Oral biolms are strongly associated with the etiology of periodontal diseases, dental caries, pulpal diseases, apical periodontitis, peri-implant diseases and candidosis (39, 48, 58, 80, 89, 94, 95, 105, 115, 137, 153) (Table 1).

Risk factors for oral biolmassociated diseases

1 The presence of a biolm alone is often not sufcient to cause disease because most oral biolm-associated diseases are complex with a multifactorial etiology. Additional factors that benet the microbial community, or make the host more susceptible, are often required for a disease to develop and progress. Visible plaque on teeth confers an elevated risk for dental caries (odds ratio = 2.75) and the presence of additional factors, such as snacking more than three 2 times daily between meals (odds ratio = 1.91), deep pits and ssures (odds ratio = 1.93), inadequate saliva ow (odds ratio = 1.37) and recreational drug use (odds ratio = 2.03) can further increase the risk (39, 46).

For periodontitis, both endogenous risk factors (such as genetics and diabetes mellitus) and exogenous risk factors (e.g. cigarette smoking and psychological stress) have been identied. Approximately 50% of the variance in clinical attachment loss in a population may be attributable to heredity, as indicated by the results of studies on twins (96). It 3 is estimated that at least 1020 modifying genes are involved in the onset and progression of chronic or aggressive periodontitis, although attempts to identify these genes have shown controversial results (84, 131). Single gene mutations that are strongly associated with periodontitis, as reported for the CTSC gene 4 ` vre syndrome, are extremely rare in the Papillon-Lefe (84, 138). Diabetes mellitus type 1 and type 2, particularly in patients with poor glycemic control, have been shown to increase the risk for periodontitis (odds ratio = 2 to 3) (44, 56, 71, 92, 93, 122, 132, 141). Probably the greatest exogenous risk factor for periodontitis, with a dose-dependent relative risk of 56, is cigarette smoking (21). More than half of all periodontitis cases in adults in the USA have been attributed to smoking (135).

Trends in dental caries and periodontal diseases

Oral biolm-associated diseases may be as old as mankind itself, as evidenced by signs of alveolar bone loss in a 3-million-year-old hominid and other human remains from later time-periods (74). One of the earliest descriptions of periodontal disease recorded was in the army of the Greek general Xenophon,

Dispatch: 11.3.10 Author Received: Journal: PRD CE: Janaki Rekha No. of pages: 18 PE: Raymond

P R D

Journal Name

Manuscript No.

Beikler & Flemmig

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

Table 1. Oral biolm-associated diseases and their consequences

References Oral biolm-associated diseases Gingivitis Periodontitis (chronic, aggressive) Necrotizing periodontal diseases Abscesses of the periodontium Periodontitis associated with endodontic lesions Dental caries Pulpitits Apical periodontitis Peri-implant diseases Candidosis Diseases and conditions that may result from oral biolm-associated diseases Tooth loss Implant failure Noma Deep neck infections* Osteomyelitis of the jaw* Maxillary sinusitis* Ludwigs angina* Orbital cellulitis* Cervicofacial actinomycosis* Septicemia* Death* See Table 3 Pjetursson et al. 2007 Enwonwu et al. 2000 (45) Vieira et al. 2008 (143) Sharkawy 2007 (125) Bomeli et al. 2009 (23) Parahitiyawa et al. 2009 (111) Parahitiyawa et al. 2009 (111) Sharkawy 2007 (125) Parahitiyawa et al. 2009 (111) Robertson and Smith 2009 (119) Mariotti 1999 (89) Flemmig 1999 (48), Tonetti & Mombelli 1999 (137) Novak 1999 (105) Meng 1999 (94) Meng 1999 (95) Domejean-Orliaguet et al. 2006 (39) Levin et al. 2009 (80) Gutmann et al. 2009 (58) Zitzmann et al. 2008 (153) Ramage et al. 2009 (115)

17

Diseases that may be associated with hematogenous spreading of oral biolm bacteria Infective endocarditis Acute bacterial myocarditis Brain abscess Liver abscess Lung abscess Cavernous sinus thrombosis Prosthetic joint infection Wilson et al. 2007 (149) Parahitiyawa et al. 2009 (111) Mueller et al. 2009 (99) Wagner et al. 2006 (144) Parahitiyawa et al. 2009 (111) Parahitiyawa et al. 2009 (111) Bartzokas et al. 1994 (19)

Diseases and conditions for which periodontal inammation is considered as a risk factor Cardiovascular disease Cerebrovascular disease Diabetes mellitus with poor glycemic control Persson and Persson 2008 (112) Dorfer et al. 2004 (40) Lim et al. 2007 (82)

dating back to 400 BC (74). Dental caries can be traced back to the upper Palaeolithic area (70,000 35,000 BC). However, compared with modern times,

dental caries may have been rare in those days (49, 79). The prevalence of caries and pulpal diseases rose dramatically, however, when the widening availabil-

Oral biolm-associated diseases

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

ity and subsequent consumption of fermentable carbohydrates in developed countries increased (75, 133). Preventive efforts over the past decades have markedly decreased caries experience in children, adolescent and young adults, in most, but not all, countries of the world (24, 147) (Fig. 1). Globally, the mean decayed, missing, lled teeth index value in 125 year-old children decreased from 1.74 in 2001 to 1.64 in 2004 (24, 146), but in some developing countries (e.g. India and China), where traditional dietary patterns and lifestyles have changed with increasing economic wealth, caries experience has risen (24, 6 113). Among 12-year-old children, the dental caries experience varies considerably in different parts of the world. It is relatively high in the Americas (decayed, missing, lled teeth index value = 2.76) and in Europe (decayed, missing, lled teeth index value = 2.56), whereas the caries experience is lowest in most of Africa (decayed, missing, lled teeth index value = 1.15) and Asia (decayed, missing, lled teeth index value = 1.12) (147) (Fig. 2). Caries experience in adults remains high, with a prevalence approaching 100% in developed countries (41). The decrease in caries prevalence in young age groups seen in developed countries has been paralleled by a pronounced increase in tooth retention among the middle aged and elderly (16). As risk factors for caries become more prevalent with increasing age (60, 66, 77), it is not surprising that tooth retention is associated with higher mean decayed, missing, lled teeth scores and an increased rate of root canal treatments (62, 63).

DMFT

2.76

2.57

1.15

1.58

1.12

WHO-regions

Fig. 2. Weighted means of decayed, missing, lled teeth (DMFT) scores in 12-year-old children in the World Health Organization (WHO) regions in 2004 (147).

DMFT decreased DMFT increased or unchanged No data available

Fig. 1. Changes in decayed, missing, lled teeth (DMFT) scores in various regions of the world. Decayed, missing, lled teeth scores have been considered as increased or decreased when the most recent decayed, missing, lled teeth values were more than 0.3 different from the previous decayed, missing, lled teeth value. Observation periods ranged from 3 to 68 years in the various regions (148).

The prevalence of periodontal diseases has shown heterogeneous trends throughout the world over recent years. The Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs has improved in some parts of Africa and Asia, whereas the prevalence of periodontitis has remained unchanged, or even increased, in other parts of Asia, America and Europe (Figs 3 and 4). In most countries the periodontal disease burden remains high, with approximately 5 20% of adults and 2% of youths affected by severe periodontitis (Fig. 5) (5, 113, 145). Although the widely used Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs allows some comparison between countries, the information needs to be interpreted with caution owing to a categorical and partialmouth assessment, which may underestimate the true prevalence of periodontal disease (15). The lack of a universally accepted denition of what constitutes a periodontitis case makes assessment of the true prevalence of periodontitis in various populations elusive (30). Epidemiological surveys that have been conducted in detail in developed countries with ready access to professional dental care provide more insight regarding the trends of periodontitis prevalence in these populations. In Oslo, Norway, the proportion of 35-year-old subjects with detectable alveolar bone loss showed a signicant decrease from 54%, in 1973, to 24%, in 2003. Furthermore, the percentage of subjects with advanced periodontal destruction was found to be reduced from 21.8%, in 1984, to 8.1%, in 2003 (127). Similar ndings were reported in 20- to ping, Sweden. The pro80-year-old subjects in Jonko portion of individuals with healthy gingivae increased from 8 to 44%, whereas the proportion of individuals

COLOR

1.48

COLOR

Beikler & Flemmig

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

COLOR

% global population

80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 1 2 3

1519 years 3544 years >65 years

CPITN 3 decreased CPITN 3 increased or unchanged No data available

Fig. 3. Prevalence trends of mild to moderate periodontitis in various regions of the world. The prevalence of Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN) three values have been considered to be decreased or increased when there was a difference of 5% between the most recently and previously reported CPITN values. Changes cover observation periods ranging from 3 to 22 years (145). Note that the increased periodontitis prevalence in the USA reported by the World Health Organization is contradicted by national data showing a reduction in periodontitis prevalence (30).

CPITN

Fig. 5. Estimated global periodontal disease prevalence. Mean Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN) scores were shown for the following age groups: 1519 years (89 countries); 3544 years (89 countries); and 6574 years (28 countries). Error bars indicate standard deviation (145).

CPITN 4 decreased CPITN 4 increased/stable No data available

Fig. 4. Trends in severe periodontitis prevalence in countries around the world. The prevalence of Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN) four values have been considered as decreased or increased when there was a difference of 5% between the most recently and previously reported CPITN values. Changes cover observation periods ranging from 3 to 22 years (145). Note that the increased periodontitis prevalence in the USA, reported by the World Health Organization, is contradicted by national data showing a reduction in periodontitis prevalence (30).

mated prevalence of periodontitis decreased from 87% (in 1955) to 4.2% in 20022004 (30). Although these numbers need to be interpreted with caution given that different periodontal assessment parameters were used and periodontitis case denitions were not uniform throughout the years, the improvement in periodontal health seen in the USA is most remarkable. Improved oral hygiene (52) and reduced smoking habits (65) have been associated with the decrease in periodontitis prevalence. Little attention, however, has been given to the fact that there are approximately 130,000 active dental hygienists in the USA, by far the greatest number of dental hygienist per capita in the world. In 1996, 42.9% of Americans (115 million) had at least one dental visit and, of these, approximately 75% (86 million Americans) had at least one dental visit for preventive care (54). Of all procedures performed in US dental ofces in 2004, more than 30% were preventive in nature (87). From 1990 to 1999 alone, the number of prophylaxes performed increased from 178.5 million to 191 million, and the number of periodontal maintenance procedures increased from 9.8 million to 12.7 million. Over the same time-period, scaling and root planing procedures decreased from 14.1 million to 10.8 million, supporting the notion of a reduced periodontal treatment need in the USA (26).

COLOR

with severe periodontitis remained largely unchanged over a 30-year observation period (64). Signicantly improved oral hygiene scores accompanied the improved periodontal health in the aforementioned populations. The most dramatic improvement in periodontal health has been reported in the USA where the esti-

Impact of oral biolm-associated diseases on quality of life

Oral biolm-associated diseases may impact an individuals ability to function as well as affect the perception of well-being in physical, mental and so-

COLOR

90

Oral biolm-associated diseases

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

cial domains of life (32). Specic instruments to assess oral health-related quality of life have been developed (59). Most of the assessments capture attributes ranging from the domains of symptoms (e.g. pain, comfort), physical aspects (eating, speech, appearance), psychological aspects (condence, mood, personality), to social aspects, such as social life, work and nances. A recent systematic review indicated that dental caries in children is associated with reduced oral health-related quality of life (18). In adolescents and adults, the impact of dental caries on oral healthrelated quality of life is less clear and appears to be most pronounced in populations exhibiting high dental caries prevalence. Among Brazilian adolescents with a high prevalence of caries (88.3%), a positive correlation was found between Oral Health Impact Prole scores, where higher scores indicate impairment of oral health-related quality of life, and decayed teeth (22). However, in a Swedish population with an overall low prevalence and low incidence of caries, oral health-related quality of life measures were unable to discriminate between individuals with high or no caries experience (108). Similarly, among adults, coronal decayed surfaces and the Root Caries Index were associated with patient-based scores only in a cohort exhibiting high disease prevalence (1.6 3.0; 0.1 0.2, respectively), but not in a cohort having a low disease prevalence (0.9 2.3; 0.02 0.1, respectively) (68). Other ndings, showing decayed teeth to be negatively associated with almost all dimensions of the Dental Impact of Daily Living and positively associated with Oral Health Impact Prole 14 scores, support the notion that untreated teeth with caries have a negative impact on perceived oral health-related quality of life (76, 78). Restorative treatment in young children with severe dental caries experience was shown to substantially improve oral health-related quality of life and positively impact families (86). Information regarding the impact of restorative measures on oral health-related quality of life in other populations and age groups is sparse. Caries, trauma and dental restorations may result in pulpal and apical diseases. Although pain is recognized as a cardinal symptom of reversible and irreversible pulpitis, symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess (58, 80), there is a paucity of information regarding the impact of these diseases on other oral health-related quality of life attributes. Arguably, the greatest and most immediate impact on patient-centered outcomes may be relieving acute pain resulting from root canal treatment of pulpal and apical diseases. Given the favorable long-term success

rates of root canal treatment, the reoccurrence of symptoms that may impact oral health-related quality of life appears to be rare (139). A comprehensive assessment of the impact of root canal treatment on oral health-related quality of life, however, is lacking. Chronic forms of periodontal diseases have long been viewed as silent diseases that are not noticed by affected patients. However, recent ndings indicating a considerable impact of periodontitis on oral healthrelated quality of life measures have challenged this concept (68, 69, 76, 78). A negative impact across a wide range of physical, social and psychological aspects of quality of life were found among individuals with periodontitis. UK oral health-related quality of life (oral health-related quality of life-UK) scores, ranging from 16 (poorest) to 80 (best), were negatively associated with patients self-reported periodontal health experiences of swollen gums, sore gums, receding gums, loose teeth, drifting teeth, bad breath and toothache. A signicant, negative correlation between the number of teeth with pocket probing depth of 5 mm and oral health-related quality of life-UK was found (103). In another study, having more than eight teeth with pocket probing depths of > 5 mm compared to having fewer than three teeth with pocket probing depths of > 5 mm was associated with worse perceived oral health (odds ratio = 1.45 and odds ratio = 2.83, respectively) (34). Using the EuroQoL assessment, pain or discomfort were found 7 among 6.1% of those with gingivitis, 11.1% of those with gingival recessions and 25.8% of individuals with pocket probing depths of 6 mm (25). With the exception of pain and eating restriction, gingival bleeding, calculus and periodontal pockets were found to be negatively associated with all Dental Impact of Daily Living measures. When gingival bleeding, calculus and number of periodontal pockets increased, respondents satisfaction regarding appearance, performance, comfort and the total Dental Impact of Daily Living score decreased (78). Among adolescents, both attachment loss (odds ratio = 2.0) and necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (odds ratio = 1.6) were signicantly associated with negative impact on oral health-related quality of life (85). In children, more than one-fth perceived bleeding and swollen gums to impact on their lives (51). Patients receiving regular periodontal supportive therapy have reported signicantly better average oral health-related quality of life-UK scores (55.7) than patients with untreated periodontitis (47.7), indicating the positive effect that periodontal therapy has on oral health-related quality of life (103). These crosssectional observations have been further substanti-

Beikler & Flemmig

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

ated by longitudinal clinical trials demonstrating that nonsurgical periodontal therapy improves oral healthrelated quality of life in patients with periodontitis (13, 69, 109). Improvements in oral health-related quality of life measures resulting from nonsurgical periodontal therapy were detected within 1 week after therapy, whereas oral health-related quality of life scores were found to deteriorate in the rst few days following periodontal ap surgery and returned to baseline levels within 1 week (109). The long-term effect of surgical periodontal therapy on oral healthrelated quality of life has not been assessed. Oral biolm-associated diseases remain the major cause for tooth loss in the developed world. Generally, caries caused by periodontal diseases were the reason for 76% (ranging from 48 to 97%) of all tooth extractions (1, 2, 4, 9, 27, 29, 70, 73, 91, 100, 107, 114, 117, 118, 130, 140) (Table 2). The number of teeth present was positively correlated with perceived satisfaction of an individuals oral condition. The presence of anterior teeth was the most signicant predictor for satisfaction, whereas the presence of molar pairs added little value to satisfaction (42). The presence of teeth is important for daily activities, including opportunity for conversation with family 8 members or others, regular physical activities and attending meetings or group outings (152). Oral Impacts on Daily Performances scores were found to be highest among dentate seniors with the lowest number of teeth (126). A minimum of 20 teeth, with 910 pairs of contacting units (including anterior teeth), is generally associated with adequate masticatory efciency, as assessed by comminution efciency and self-reported masticatory ability. However, there is marked variation in subjective measures of esthetics and psychosocial comfort among age groups, social classes, cultures, regions and countries (3, 55). Restoring edentulous jaws with conventional complete dentures has resulted in an improvement in oral health-related quality of life, as measured using Oral Health Impact Prole scores (6, 7). Compelling evidence has been presented in a recently published systematic review that edentulous patients are more satised with implant-supported overdentures than conventional complete dentures, particularly in the mandible. Furthermore, implant-supported overdentures may signicantly improve oral healthrelated quality of life (134). Evidence to support an impact of mandibular implant-supported overdenture on perceived general health, however, is lacking (43). For the edentulous maxilla, implant-supported prostheses were generally rated as not different from conventional completed maxillary dentures (134).

In partially edentulous patients (Kennedy Class I), the replacement of at least the rst molars using a removable dental prosthesis has been shown to improve Oral Health Impact Prole scores. It, however, did not show any advantage over a xed premolar occlusion in terms of oral health-related quality of life measures (151). The quality of removable partial dentures, as assessed by denture stability and esthetics, is directly associated with the perceived quality of life in partially edentulous patients (67). Information regarding oral health-related quality of life or satisfaction outcomes for the majority of other forms of prosthetic dentistry is sparse.

Systemic implications of oral biolm-associated diseases

Oral biolm-associated diseases may affect systemic health by (i) spreading infections to adjacent tissues and spaces, (ii) hematogenous dissemination of oral biolm bacteria, or (iii) through inammatory 9 mechanisms. Acute forms of odontogenic infections may spread into the adjacent tissues, causing osteomyelitis of the jaws, maxillary sinusitis, noma, deep neck infections, Ludwigs angina, orbital cellulitis, skin ulcers, cervicofacial actinomycosis, septicemia and, in rare cases, even death (23, 45, 111, 119, 125, 143) (Table 1). Odontogenic infections can be life threatening. Mortality rates of descending necrotizing mediastinitis, resulting from odontogenic infections and noma, have been reported to range from 50 to 80% when no adequate therapy was rendered (88). It is therefore not surprising that in medieval Europe, dental caries and periodontal diseases were associated with an increased risk of death (37). According to church registries from the 18th and 19th centuries, dental fever was given as the cause of death in 30% of infants (8). Although medical advances and improved access to care for many populations have drastically reduced the mortality rate resulting from dental infections, there are still approximately 21,000 hospital admissions and at least 150 deaths caused by odontogenic infections in the USA every year (53) and approximately 770,000 cases of life-threatening noma worldwide (17, 98). Oral biolms represent an abundant reservoir of microorganisms that may spread via transient bacteremia, as demonstrated by the types of oral biolms isolated from infections remote from the oral cavity (81). Shedding and subsequent hematogenous dissemination of oral biolm bacteria have been associated with some forms of infective endocarditis,

Oral biolm-associated diseases

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

Table 2. Reasons presented for tooth extraction related to oral biolm-associated diseases in various geographic regions

Author Cahen et al. (27) Kay and Blinkhorn (70) Agerholm and Sidi (1) Chauncey et al. (29) Klock et al. (73) Stephens et al. (130) Reich and Hiller (117) Phipps and Stevens (114) Ong et al. (107) Angelillo et al. (9) Murray et al. (100) McCaul et al. (91) Trovik et al. (140) Richards et al. (118) Aida et al. (2) Al-Shammari et al. (4) Weighted mean Year 1985 1986 1988 1989 1991 1991 1993 1995 1996 1996 1997 2001 2001 2005 2006 2006 Country France Scotland Enland Wales US Norway Canada Germany US Singapore Italy Canada Scotland Norway South Wales Japan Kuwait Extracted teeth Dental caries (%) (n) 14621 2190 5274 1142 985 2510 1215 1877 272 1056 1710 2558 1495 558 9115 2783 49 50 48 33 35 63 21 51 35 34 29 55 40 59 33 44 Periodontal disease (%) 32 21 27 19 19 34 27 35 36 33 26 17 24 29 42 37 Total (%) 81 71 75 52 54 97 48 86 71 68 55 72 64 88 75 81 76

acute bacterial myocarditis, brain abscess, liver abscess, lung abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis and prosthetic joint infections (19, 99, 102, 111, 142, 144, 149) (Table 1). The incidence of organ infections associated with oral biolm bacteria appears to be extremely low as the supporting evidence is mostly based on case reports (99, 102, 111, 142, 144). The incidence of infective endocarditis caused by viridans group streptococci is estimated to be 1.76.2 cases per 100,000 patient years. Men are twice as often affected as women, and the incidence of infective endocarditis increases with age (101). In Finland, the number of septicemias in adults caused by viridans

group streptococci has almost doubled over the past decade. Interestingly, this number is directly proportional to the number of individuals remaining dentate throughout their lives (116). One can only speculate whether the increased retention of teeth in seniors, together with an increased life expectancy in many parts of the world, may lead to a rise in infective endocarditis. The notion that oral biolms may impact systemic health by inammatory mechanisms is supported by cross-sectional studies reporting elevated systemic inammatory markers in patients with periodontitis (28, 33, 36, 83, 128). Strong evidence supports the oral

Beikler & Flemmig

1 systemic link between periodontitis and cardiovascu2 lar diseases, cerebrovascular diseases and diabetes 3 mellitus, all of which have an inammatory etiology. A 4 number of cross-sectional and cohort studies have 5 demonstrated consistent associations between peri6 odontitis and cardiovascular disease, irrespective of 7 common underlying risk factors or confounders such 8 as smoking, age, education, body mass index and 9 lifestyle factors (112). Hazard ratios and relative risk 10 ratios for fatal and nonfatal coronary events have been 11 reported to range from 1.5 to 2.0 in individuals with 12 periodontitis (20, 38); the adjusted risk ratio for cere13 bral ischemia is 7.4 (31, 40). In diabetic patients, peri14 odontitis has been identied as a risk factor for poor 15 glycemic control (31, 82, 104, 132). The association of 16 periodontitis with adverse pregnancy outcomes, 17 osteoporosis, cancer and chronic obstructive pulmo18 nary diseases remains controversial (14, 47, 72, 150). 19 There is some evidence to support that treatment 20 of periodontitis may improve glycemic control in 21 diabetic patients (50). Periodontal therapy also has 22 been shown to reduce inammatory biomarkers, 23 improve surrogate measures of vascular endothelial 24 function (136) and thereby possibly exert an effect on 25 inammatory vascular diseases. However, direct 26 evidence that periodontal therapy may reduce the 27 risk for cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases is 28 lacking. With regard to adverse pregnancy outcomes, 29 an intervention trial with more than 800 enrolled 30 patients demonstrated that treatment of periodontal 31 disease improved periodontal conditions, but did not 32 signicantly reduce the risk of adverse pregnancy 33 outcomes (97). 34 35 36 Financial expenditures for dental 37 services related to oral biolm38 39 associated diseases 40 In order to estimate the costs of managing oral bio41 lm-associated diseases, the national expenditures 42 for professional dental services related to these dis43 eases were calculated. For this purpose, the 500 + 44 45 10 dental procedures listed in the Current Dental Terminology 2009 2010 of the American Dental Asso46 ciation (11) were categorized based on whether they 47 are used primarily for the prevention (A), diagnosis, 48 or treatment of oral biolm-associated diseases and 49 their sequelae, primarily for conditions unrelated to 50 oral biolm-associated diseases (B) or for oral bio51 lm-associated diseases as well as other oral condi52 tions (C). Although there may be instances in which 53

procedures that were assigned to category A or category B are used for other purposes, the frequency of this occurrence was considered to be negligible. Where reliable data were available, the proportions of category C procedures used for oral biolm-associated diseases or other oral conditions were determined. For example, 86% of tooth extractions in the USA are the result of caries (114), while 14% of extractions were considered to be related to conditions other than oral biolm-associated diseases. The same proportions (i.e. 8614%) were applied to restorations, such as xed prostheses or implant-supported restorations, aimed at replacing lost teeth. For other procedures where no reliable data were available, the proportion of each procedure used for the management of biolm-associated diseases was estimated using expert opinion (Table 3). Using the ADA 200506 Survey of Dental Services Rendered 11 (10), and the 50th percentile of the national fees for dental procedures (12), it was estimated that 87% of all dental procedures rendered were related to the prevention, diagnosis and management of oral biolm-associated diseases in dental ofces; the cost of these dental procedures corresponded to 90% of the national expenditures for dental services, amounting to $81 billion in 2006 (124). These gures do not include the approximately $9 billion in expenditures for oral hygiene products sold in the USA in 2006 (90).

Oral biolm-associated diseases are among the most costly medical conditions

The estimated national expenditures for oral biolmassociated diseases in the USA have almost doubled from 1997 to 2006. In 2006, the estimated national expenditures for oral biolm-associated diseases totaled $81 billion and were greater than for any one of the ve most expensive medical conditions reported by the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: heart conditions ($78.0 billion); trauma-related disorders ($68.1 billion); cancer ($57.5 billion); mental disorders ($57.2 billion); and pulmonary conditions ($51.3 billion) (Fig. 6) (106, 124, 129).

Concluding remarks

Oral biolm-associated diseases, and their subsequent diseases and conditions, have broad impli-

Oral biolm-associated diseases

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

Table 3. Procedures assumed to be performed that are unrelated to oral biolm-associated diseases

Estimated percentage unrelated to oral biolm-associated diseases (%)

18

CDT code Diagnostic D0120 D0140 D0150 D0160 D0170 D0180 D0210D0230 D0270D0274 D0330 D0340

Description

Periodic oral evaluation* Limited oral evaluation* Comprehensive oral evaluation* Detailed and extensive oral evaluation* Re-evaluation* Comprehensive periodontal evaluation* Intra-oral radiographs, peri-apical radiographs* Bitewing radiographs* Panoramic lm* Cephalometric lm

10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 23 100

D0350 D0431

Oral facial photographic images Adjunctive test for mucosal abnormalities

100 100

D0460 D0470 Preventive D1510 1515 D1520 1525

Pulp vitality tests* Diagnostic casts*

10 10

Space maintainer xed Space maintainer removable

100 100

Restorative D2330 D2391 Resin-based composite one surface, posterior D27102794 D2950 Core buildup D29522954, 2957 D29602962 Labial veneer Endodontics D33513353 Apexication recalcication 100 Post and core 10 100 Crown single restoration 10 10 Resin-based composite one surface, anterior 20 20

Beikler & Flemmig

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

Table 3. (Continued)

Estimated percentage unrelated to oral biolm-associated diseases (%)

18

CDT code Periodontics D4270,4271

Description

100 Free soft tissue graft, subepithelial connective tissue graft

Maxillofacial prosthetics D5982 5988 Implant services D6010 D6053 6054 Implant abutment-supported removable denture D6056 D6057 Custom abutment D60586067, 6094 Abutment- or implantsupported supported crown D60686077, 6194 Prosthodontics (xed) D62056252 D67106792, 6794 Oral and maxillofacial surgery D7111, 7140 D7210, 7210 D7220 D72307241 D7261 D7280 D7283 D7340 7350 D7410-7411 D7412 Extraction Surgical extraction

Surgical stent, surgical splint

100

Surgical placement of implant body

14 14

Prefabricated abutment

14 14 14

Abutment- or implantsupported retainer

14

Pontic Crown

24 24

14 14 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

Removal of impacted tooth soft tissue Removal of impacted tooth bony Primary closure of a sinus perforation Surgical access of an unerupted tooth Placement of device to facilitate eruption Vestibuloplasty ridge extension Excision of benign lesion Excision of benign lesion, complicated

10

Oral biolm-associated diseases

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

Table 3. (Continued)

Estimated percentage unrelated to oral biolm-associated diseases (%) 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

18

CDT code D74137415 D7450 7460 D7451 7461 D7471 7485 D7472 7473 D7610 7620 D7630 7640 D7670 7671 D7680 D7710 7720 D7730 7740 D7780 D7820 D7865 D7870 D78727877 D7880 D7941 7943 D7945 D7950 D7955 D7960 7963 Orthodontics D8010 D8020 D8030 D8040 D8050

Description Excision of malignant lesion Removal of benign odontogenic cyst or tumor Removal of benign odontogenic cyst or tumor Removal of lateral exostosis Removal of torus palatinus or torus mandibularis Simple fracture maxilla Simple fracture mandible Alveolus simple Facial bones simple complicated reduction Compound facture maxilla Compound fracture mandible Facial bones compound complicated reduction Closed reduction of dislocation Arthroplasty Arthrocentesis Arthroscopy surgical Occlusal orthotic device Osteotomy mandibular rami Osteotomy body of mandible Osseous, osteoperiosteal, or cartilage graft Repair of maxillofacial soft and or hard tissue defect Frenulectomy or frenotomy

Limited orthodontic treatment primary dentition Limited orthodontic treatment transitional dentition Limited orthodontic treatment adolescent dentition Limited orthodontic treatment adult dentition Interceptive orthodontic treatment of the primary dentition

100 100 100 100 100

11

Beikler & Flemmig

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

Table 3. (Continued)

Estimated percentage unrelated to oral biolm-associated diseases (%) 100

18

CDT code D8060

Description Interceptive orthodontic treatment of the transitional dentition Comprehensive orthodontic treatment of the transitional dentition Comprehensive orthodontic treatment of the adolescent dentition Comprehensive orthodontic treatment of the adult dentition Removable appliance therapy Fixed appliance therapy Pre-orthodontic treatment visit Periodic orthodontic treatment visit Orthodontic retention Orthodontic treatment (alternative billing) Repair of orthodontic appliance Replacement of lost or broken retainer Unspecied orthodontic procedure

D8070

100

D8080

100

D8090

100

D8210 D8220 D8660 D8670 D8680 D8690 D8691 D8692 D8999 Adjunctive general services D9220 D9221

100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

Deep sedation general anesthesia rst 30 minutes Deep sedation general anesthesia each additional 15 minutes Analgesia, anxiolysis, inhalation of nitrous oxide Intravenous conscious sedation analgesia Nonintravenous conscious sedation Therapeutic parenteral drug Desensitizing medicament resin Behavior management

100 100

D9230 D9241 9242 D9248 D9610 D9910 9911 D9920

100 100 100 100 100 100

12

Oral biolm-associated diseases

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

Table 3. (Continued)

Estimated percentage unrelated to oral biolm-associated diseases (%) 100 100 100 100 100 100

18

CDT code D9940 9941 D9942 D9951 9952 D9970 D9972 9973 D9974

Description Occlusal guard athletic mouthguard Repair and or reline of occlusal guard Occlusal adjustment Enamel microabrasion External bleaching Internal bleaching

COLOR

90 80 70 60

50 40 30 20 10 0 1997 2002 Year Oral biofilm-associated diseases Heart conditions Trauma-related disorders Cancer Mental disorders Pulmonary conditions 2006

Fig. 6. National expenditures for the most costly medical conditions and oral biolm-associated diseases in the USA in 1997, 2002 and 2006. Expenditures are dened as the sum of direct payments for care provided during the year, including out-of-pocket payments and payments by private insurance, Medicaid, Medicare and other sources. International Classication of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) condition codes are aggregated into clinically meaningful categories that group similar conditions using Clinical Classication System (CCS) software. Cancer includes CCS codes 1145; heart conditions, CCS codes 96, 97 and 100108; pulmonary 16 conditions (COPD, asthma), CCS codes 127134; trauma, CCS codes 225236, 239, 240 and 244; and mental disorders, CCS codes 650663. Expenditures for oral biolm-associated diseases are estimates corresponding to 90% of the national expenditures for dental services (106, 124, 129).

cations on systemic health and oral health-related quality of life, and pose a signicant cost burden on societies. Considerable strides have been made in the prevention and management of oral biolm-associated diseases and their sequelae. Caries is a formidable example of the success of preventive measures, as shown by the substantial decline in its prevalence reported by many developed countries. With respect to the prevention of periodontitis, however, success of prevention is less apparent and varies greatly between populations. Despite the great progress that has been made, large portions of the worlds population remain affected by oral biolm-associated diseases. If the disease burden is to be further reduced, new and more cost-effective prevention and treatment strategies are needed that result in sustained oral health with minimal reliance on patients compliance and regular access to professional dental care. The following assumptions were made with regard to the proportion of procedures that may be employed for both oral biolm-associated and other conditions. as 10% of all therapeutic procedures were found to be unrelated to oral biolm-associated diseases, the same proportion of all diagnostic procedures was assumed to be unrelated to oral biolm-associated diseases. Panoramic lms include those taken by orthodontists. 20% of all resin-based composites are used for noncarious cervical lesions. 10% of all crowns, core buildup, post and core are performed for esthetic reasons. as 14% of all teeth are extracted for reasons other than caries or periodontal disease, the same proportion of procedures aimed at replacing lost teeth

$ billions

13

Beikler & Flemmig

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

was assumed to be unrelated to oral biolm-associated diseases. Fixed prosthodontics procedures include 10% performed for esthetic reasons. average percentage of extractions performed for reasons other than caries or periodontal disease based on the data presented in Table 2.

17.

18.

References

1. Agerholm DM, Sidi AD. Reasons given for extraction of permanent teeth by general dental practitioners in England and Wales. Br Dent J 1988: 164: 345348. 2. Aida J, Ando Y, Akhter R, Aoyama H, Masui M, Morita M. Reasons for permanent tooth extractions in Japan. J Epidemiol 2006: 16: 214219. 3. Akifusa S, Soh I, Ansai T, Hamasaki T, Takata Y, Yohida A, Fukuhara M, Sonoki K, Takehara T. Relationship of number of remaining teeth to health-related quality of life in community-dwelling elderly. Gerodontology 2005: 22: 9197. 4. Al-Shammari KF, Al-Ansari JM, Al-Melh MA, Al-Khabbaz AK. Reasons for tooth extraction in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract 2006: 15: 417422. 5. Albandar JM, Brown LJ, Loe H. Clinical features of early-onset periodontitis. J Am Dent Assoc 1997: 128: 1393 1399. 6. Allen F, Locker D. A modied short version of the oral health impact prole for assessing health-related quality of life in edentulous adults. Int J Prosthodont 2002: 15: 446 450. 7. Allen PF, Thomason JM, Jepson NJ, Nohl F, Smith DG, Ellis J. A randomized controlled trial of implant-retained mandibular overdentures. J Dent Res 2006: 85: 547551. 8. Alt KW NN, Held P, Meyer C, Robach A, Burwinkel M hne als Gesundheits- und Mortalita tsrisiko Rahden. Za 12 Westfalia, Germany: Marie Leidorf Verlag 2006: 2542. 9. Angelillo IF, Nobile CG, Pavia M. Survey of reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Italy. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996: 24: 336340. 10. Anonymous. 200506 Survey of dental services rendered. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association, 2007. 11. Anonymous. Current Dental Terminology 20092010. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association, 2008. 12. Anonymous. National dental advisory service comprehensive fee report 2007. In, 2007. 13. Aslund M, Suvan J, Moles DR, DAiuto F, Tonetti MS. Effects of two different methods of non-surgical periodontal therapy on patient perception of pain and quality of life: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol 2008: 79: 10311040. 14. Azarpazhooh A, Leake JL. Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol 2006: 77: 14651482. 15. Baelum V, Fejerskov O, Manji F, Wanzala P. Inuence of CPITN partial recordings on estimates of prevalence and severity of various periodontal conditions in adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1993: 21: 354359. 16. Baelum V, van Palenstein Helderman W, Hugoson A, Yee R, Fejerskov O. A global perspective on changes in the burden

19.

20.

21. 22.

23.

24. 25.

26. 27.

28. 29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35. 36.

of caries and periodontitis: implications for dentistry. J Oral Rehabil 2007: 34: 872906; discussion 940. Baratti-Mayer D, Pittet B, Montandon D, Bolivar I, Bornand JE, Hugonnet S, Jaquinet A, Schrenzel J, Pittet D; Geneva Study Group on Noma. Noma: an infectious disease of unknown aetiology. Lancet Infect Dis 2003: 3: 419431. Barbosa TS, Gaviao MB. Oral health-related quality of life in children: part II. Effects of clinical oral health status. A systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg 2008: 6: 100107. Bartzokas CA, Johnson R, Jane M, Martin MV, Pearce PK, Saw Y. Relation between mouth and haematogenous infection in total joint replacements. BMJ 1994: 309: 506 508. Beck J, Garcia R, Heiss G, Vokonas PS, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol 1996: 67: 11231137. m J. Tobacco smoking and chronic destructive Bergstro periodontal disease. Odontology 2004: 92: 18. Biazevic MG, Rissotto RR, Michel-Crosato E, Mendes LA, Mendes MO. Relationship between oral health and its impact on quality of life among adolescents. Braz Oral Res 2008: 22: 3642. Bomeli SR, Branstetter BFt, Ferguson BJ. Frequency of a dental source for acute maxillary sinusitis. Laryngoscope 2009: 119: 580584. Bratthall D. Estimation of global DMFT for 12-year-olds in 2004. Int Dent J 2005: 55: 370372. Brennan DS, Spencer AJ, Roberts-Thomson KF. Quality of life and disability weights associated with periodontal disease. J Dent Res 2007: 86: 713717. Brown LJ, Johns BA, Wall TP. The economics of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 2002: 29: 223234. Cahen PM, Frank RM, Turlot JC. A survey of the reasons for dental extractions in France. J Dent Res 1985: 64: 1087 1093. Chapple IL. The impact of oral disease upon systemic health symposium overview. J Dent 2009: 37: S568S571. Chauncey HH, Glass RL, Alman JE. Dental caries. Principal cause of tooth extraction in a sample of US male adults. Caries Res 1989: 23: 200205. Cobb CM, Williams KB, Gerkovitch MM. Is the prevalence of periodontitis in the USA in decline? Periodontol 2000 2009: 50: 1324. rhi V, Collin HL, Uusitupa M, Niskanen L, Kontturi-Na Markkanen H, Koivisto AM, Meurman JH. Periodontal ndings in elderly patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol 1998: 69: 962966. Coons SJ, Rao S, Keininger DL, Hays RD. A comparative review of generic quality-of-life instruments. Pharmacoeconomics 2000: 17: 1335. Craig RG, Yip JK, So MK, Boylan RJ, Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Relationship of destructive periodontal disease to the acute-phase response. J Periodontol 2003: 74: 10071016. Cunha-Cruz J, Hujoel PP, Kressin NR. Oral health-related quality of life of periodontal patients. J Periodontal Res 2007: 42: 169176. Davies D. Understanding biolm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003: 2: 114122. Deliargyris EN, Madianos PN, Kadoma W, Marron I, Smith SC Jr, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease in patients with acute myocardial infarction: prevalence and

14

Oral biolm-associated diseases

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

37. 13 38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48. 49. 50. 51.

52.

53. 54.

55. 56.

contribution to elevated C-reactive protein levels. Am Heart J 2004: 147: 10051009. Dewitte SN, Bekvalac J. Oral health and frailty in the medieval English cemetery of St Mary Graces. Am J Phys Anthropol 2009: ???: ??????. Dietrich T, Jimenez M, Krall Kaye EA, Vokonas PS, Garcia RI. Age-dependent associations between chronic periodontitis edentulism and risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation 2008: 117: 16681674. Domejean-Orliaguet S, Gansky SA, Featherstone JD. Caries risk assessment in an educational environment. J Dent Educ 2006: 70: 13461354. rfer CE, Becher H, Ziegler CM, Kaiser C, Lutz R, Jo rss D, Do ltmann S, Preusch M, Grau AJ. The Lichy C, Buggle F, Bu association of gingivitis and periodontitis with ischemic stroke. J Clin Periodontol 2004: 31: 396401. Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, Lewis BG, Barker LK, Thornton n-Aguilar ED, Horowitz AM, Li CH. Evans G, Eke PI, Beltra Trends in oral health status: United States, 19881994 and 19992004. Vital Health Stat 2007: 11: 192. Elias AC, Sheiham A. The relationship between satisfaction with mouth and number, position and condition of teeth: studies in Brazilian adults. J Oral Rehabil 1999: 26: 5371. Emami E, Heydecke G, Rompre PH, de Grandmont P, Feine JS. Impact of implant support for mandibular dentures on satisfaction, oral and general health-related quality of life: a meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Clin Oral Implants Res 2009: 20: 533544. Emrich LJ, Shlossman M, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol 1991: 62: 123131. Enwonwu CO, Falkler WA, Idigbe EO. Oro-facial gangrene (noma cancrum oris): pathogenetic mechanisms. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2000: 11: 159171. Featherstone JD, Domejean-Orliaguet S, Jenson L, Wolff M, Young DA Caries risk assessment in practice for age 6 through adult. J Calif Dent Assoc 2007: 35: 703707, 710 703. Fitzpatrick SG, Katz J. The Association Between Periodontal Disease and Cancer: a Review of the Literature. J Dent 2010: 38: 8395. Flemmig TF. Periodontitis. Ann Periodontol 1999: 4: 3238. Forshaw RJ. Dental health and disease in ancient Egypt. Br Dent J 2009: 206: 421424. Garcia R. Periodontal treatment could improve glycaemic control in diabetic patients. Evid Based Dent 2009: 10: 2021. Gherunpong S, Tsakos G, Sheiham A. The prevalence and severity of oral impacts on daily performances in Thai primary school children. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004: 2: 57. Gjermo PE. Impact of periodontal preventive programmes on the data from epidemiologic studies. J Clin Periodontol 2005: 32 (Suppl. 6): 294300. Goldberg MTR. Oral and Maxillofacial Infections, 4th edn.: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2002: 158-188. Goodman HS, Manski MC, Williams JN, Manski RJ. An analysis of preventive dental visits by provider type, 1996. J Am Dent Assoc 2005: 136: 221228. Gotfredsen K, Walls AW. What dentition assures oral function? Clin Oral Implants Res 2007: 18 (Suppl. 3): 3445. Grossi SG. Assessment of risk for periodontal disease. I. Risk indicators for attachment loss. J Periodontol 1994: 65: 260.

57. Grossner-Schreiber B, Teichmann J, Hannig M, Dorfer C, Wenderoth DF, Ott SJ. Modied implant surfaces show different biolm compositions under in vivo conditions. Clin Oral Implants Res 2009: 20: 817826. 58. Gutmann JL, Baumgartner JC, Gluskin AH, Hartwell GR, Walton RE. Identify and dene all diagnostic terms for periapical periradicular health and disease States. J Endod 2009: 35: 16581674. 59. Hebling E, Pereira AC. Oral health-related quality of life: a critical appraisal of assessment tools used in elderly people. Gerodontology 2007: 24: 151161. 60. Hintao J, Teanpaisan R, Chongsuvivatwong V, Ratarasan C, n G. The microbiological proles of saliva, supraDahle gingival and subgingival plaque and dental caries in adults with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2007: 22: 175181. 61. Hojo K, Nagaoka S, Ohshima T, Maeda N. Bacterial interactions in dental biolm development. J Dent Res 2009: 88: 982990. thberg C, Helkimo AN, Lundin SA, 62. Hugoson A, Koch G, Go din B, Sondell K. Oral health of individuals Norderyd O, Sjo nko ping, Sweden during 30 years aged 380 years in Jo (1973-2003). I. Review of ndings on dental care habits and knowledge of oral health. Swed Dent J 2005: 29: 125138. thberg C, Helkimo AN, Lundin SA, 63. Hugoson A, Koch G, Go din B, Sondell K. Oral health of individuals Norderyd O, Sjo nko ping, Sweden during 30 years aged 380 years in Jo (1973-2003). II. Review of clinical and radiographic ndings. Swed Dent J 2005: 29: 139155. 64. Hugoson A, Sjodin B, Norderyd O. Trends over 30 years, 1973-2003, in the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 2008: 35: 405414. m J. A 65. Hujoel PP, del Aguila MA, DeRouen TA, Bergstro hidden periodontitis epidemic during the 20th century? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003: 31: 16. 66. Imazato S, Ikebe K, Nokubi T, Ebisu S, Walls AW. Prevalence of root caries in a selected population of older adults in Japan. J Oral Rehabil 2006: 33: 137143. 67. Inukai M, Baba K, John MT, Igarashi Y. Does removable partial denture quality affect individuals oral health? J Dent Res 2008: 87: 736739. 68. Jones JA, Kressin NR, Miller DR, Orner MB, Garcia RI, Spiro A III. Comparison of patient-based oral health outcome measures. Qual Life Res 2004: 13: 975985. 69. Jowett AK, Orr MT, Rawlinson A, Robinson PG. Psychosocial impact of periodontal disease and its treatment with 24-h root surface debridement. J Clin Periodontol 2009: 36: 413418. 70. Kay EJ, Blinkhorn AS. The reasons underlying the extraction of teeth in Scotland. Br Dent J 1986: 160: 287290. 71. Khader YS, Dauod AS, El-Qaderi SS, Alkafajei A, Batayha WQ. Periodontal status of diabetics compared with nondiabetics: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complications 2006: 20: 5968. 72. Kim J, Amar S. Periodontal disease and systemic conditions: a bidirectional relationship. Odontology 2006: 94: 1021. 73. Klock KS, Haugejorden O. Primary reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Norway: changes from 1968 to 1988. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1991: 19: 336341. 74. Langsjoen O, ed. Diseases of the dentition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 1998: 393412.

15

Beikler & Flemmig

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

75. Larsen CS. Biological changes in human populations with agriculture. Annual Review of Anthropology 1995: 24: 185 213. 76. Lawrence HP, Thomson WM, Broadbent JM, Poulton R. Oral health-related quality of life in a birth cohort of 32-year olds. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2008: 36: 305316. 77. Le Pera AF, Mahevich RA, Silverstein H. Xerostomia and its effects on the dentition. J N J Dent Assoc 2005: 76: 1921. 78. Leao A, Sheiham A. Relation between clinical dental status and subjective impacts on daily living. J Dent Res 1995: 74: 14081413. 79. Leek FF. Observations on the Dental Pathology Seen in Ancient Egyptian Skulls. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 1966: 52: 5964. 80. Levin LG, Law AS, Holland GR, Abbott PV, Roda RS. Identify and dene all diagnostic terms for pulpal health and disease States. J Endod 2009: 35: 16451657. 81. Li X, Kolltveit KM, Tronstad L, Olsen I. Systemic diseases caused by oral infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000: 13: 547 558. 82. Lim LP, Tay FB, Sum CF, Thai AC. Relationship between markers of metabolic control and inammation on severity of periodontal disease in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Clin Periodontol 2007: 34: 118123. 83. Linden GJ, McClean K, Young I, Evans A, Kee F. Persistently raised C-reactive protein levels are associated with advanced periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 2008: 35: 741747. 84. Loos BG, John RP, Laine ML. Identication of genetic risk factors for periodontitis and possible mechanisms of action. J Clin Periodontol 2005: 32: 159. 85. Lopez R, Baelum V. Oral health impact of periodontal diseases in adolescents. J Dent Res 2007: 86: 11051109. 86. Malden PE, Thomson WM, Jokovic A, Locker D. Changes in parent-assessed oral health-related quality of life among young children following dental treatment under general anaesthetic. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2008: 36: 108117. 87. Manski RJBE. Dental use, expenses, private dental coverage, and changes, 1996 and 2004. In: MEPS Chartbook No 17. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and 14 Quality, 2007. 88. Marck KW. A history of noma, the Face of Poverty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003: 111: 17021707. 89. Mariotti A. Dental plaque-induced gingival diseases. Ann Periodontol 1999: 4: 719. 90. Markets Ra. Oral Hygiene: Global industry guide. In, 2009. 91. McCaul LK, Jenkins WM, Kay EJ. The reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Scotland: a 15-year follow-up study. Br Dent J 2001: 190: 658662. 92. Mealey B. American Academy of Periodontology Position Paper - Diabetes and periodontal diseases. J Periodontol 2000: 71: 664. 93. Mealey BL, Oates TW. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases. J Periodontol 2006: 77: 12891303. 94. Meng HX. Periodontal abscess. Ann Periodontol 1999: 4: 7983. 95. Meng HX. Periodontic-endodontic lesions. Ann Periodontol 1999: 4: 8490. 96. Michalowicz BS, Diehl SR, Gunsolley JC, Sparks BS, Brooks CN, Koertge TE, Califano JV, Burmeister JA, Schenkein HA.

97.

98. 99.

100.

101. 102.

103.

104.

105. 106.

107.

108.

109.

110. 111.

112.

113.

114.

Evidence of a substantial genetic basis for risk of adult periodontitis. J Periodontol 2000: 71: 16991707. Michalowicz BS, Hodges JS, DiAngelis AJ, Lupo VR, Novak MJ, Ferguson JE, Buchanan W, Boll J, Papapanou PN, Mitchell DA, Matseoane S, Tschida PA; OPT Study. Treatment of periodontal disease and the risk of preterm birth. N Engl J Med 2006: 355: 18851894. Mignogna MD, Fedele S. The neglected global burden of chronic oral diseases. J Dent Res 2006: 85: 390391. binger S, Walter C, Flu ckiger U, Mueller AA, Saldamli B, Stu Merlo A, Schwenzer-Zimmerer K, Zeilhofer HF, Zimmerer S. Oral bacterial cultures in nontraumatic brain abscesses: results of a rst-line study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009: 107: 469476. Murray H, Clarke M, Locker D, Kay EJ. Reasons for tooth extractions in dental practices in Ontario, Canada according to tooth type. Int Dent J 1997: 47: 38. Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB. Infective endocarditis in adults. N Engl J Med 2001: 345: 13181330. Mylonas AI, Tzerbos FH, Mihalaki M, Rologis D, Boutsikakis I. Cerebral abscess of odontogenic origin. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2007: 35: 6367. Needleman I, McGrath C, Floyd P, Biddle A. Impact of oral health on the life quality of periodontal patients. J Clin Periodontol 2004: 31: 454457. Nelson RG, Shlossman M, Budding LM, Pettitt DJ, Saad MF, Genco RJ, Knowler WC. Periodontal disease and NIDDM in Pima Indians. Diabetes Care 1990: 13: 836840. Novak MJ. Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis. Ann Periodontol 1999: 4: 7478. Olin GLRJ. The ve most costly medical conditions, 1997 and 2002: Estimates for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. In: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Qual15 ity, 2005. Ong G, Yeo JF, Bhole S. A survey of reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Singapore. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996: 24: 124127. Oscarson N, Kallestal C, Lindholm L. A pilot study of the use of oral health-related quality of life measures as an outcome for analysing the impact of caries disease among Swedish 19-year-olds. Caries Res 2007: 41: 8592. Ozcelik O, Haytac MC, Seydaoglu G. Immediate postoperative effects of different periodontal treatment modalities on oral health-related quality of life: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2007: 34: 788796. Palmer RJ. Oral bacterial biolms history in progress. Microbiology 2009: 155: 21132114. Parahitiyawa NB, Jin LJ, Leung WK, Yam WC, Samaranayake LP Microbiology of odontogenic bacteremia: beyond endocarditis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009: 22: 4664, Table of Contents. Persson GR, Persson RE. Cardiovascular disease and periodontitis: an update on the associations and risk. J Clin Periodontol 2008: 35: 362379. Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ 2005: 83: 661669. Phipps KR, Stevens VJ. Relative contribution of caries and periodontal disease in adult tooth loss for an HMO dental population. J Public Health Dent 1995: 55: 250 252.

16

Oral biolm-associated diseases

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

115. Ramage G, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Lopez-Ribot J. Our current understanding of fungal biolms. Crit Rev Microbiol 2009: 35: 340355. 116. Rautemaa R, Lauhio A, Cullinan MP, Seymour GJ. Oral infections and systemic diseasean emerging problem in medicine. Clin Microbiol Infect 2007: 13: 10411047. 117. Reich E, Hiller KA. Reasons for tooth extraction in the western states of Germany. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1993: 21: 379383. 118. Richards W, Ameen J, Coll AM, Higgs G. Reasons for tooth extraction in four general dental practices in South Wales. Br Dent J 2005: 198: 275278. 119. Robertson D, Smith AJ. The microbiology of the acute dental abscess. J Med Microbiol 2009: 58: 155162. 120. Rocha CT, Rossi MA, Leonardo MR, Rocha LB, NelsonFilho P, Silva LA. Biolm on the apical region of roots in primary teeth with vital and necrotic pulps with or without radiographically evident apical pathosis. Int Endod J 2008: 41: 664669. 121. Sachdeo A, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Biolms in the edentulous oral cavity. J Prosthodont 2008: 17: 348356. 122. Salvi GE, Carollo-Bittel B, Lang NP. Effects of diabetes mellitus on periodontal and peri-implant conditions: update on associations and risks. J Clin Periodontol 2008: 35: 398409. 123. Schaudinn C, Gorur A, Keller D, Sedghizadeh PP, Costerton JW. Periodontitis: an archetypical biolm disease. J Am Dent Assoc 2009: 140: 978986. 124. Services CfMM. National health expenditure data. In, 2009. 125. Sharkawy AA Cervicofacial actinomycosis and mandibular osteomyelitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2007: 21: 543556, viii. 126. Sheiham A, Steele JG, Marcenes W, Tsakos G, Finch S, Walls AW. Prevalence of impacts of dental and oral disorders and their effects on eating among older people; a national survey in Great Britain. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001: 29: 195203. 127. Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Eriksen HM, Hansen BF. Trends in periodontal health among 35-year-olds in Oslo, 19732003. J Clin Periodontol 2007: 34: 867872. 128. Slade GD, Offenbacher S, Beck JD, Heiss G, Pankow JS. Acute-phase inammatory response to periodontal disease in the US population. J Dent Res 2000: 79: 4957. 129. Soni A The ve most costly conditions, 1996 and 2006: Estimates for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. in: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Reasearch and Quality, 2009. 130. Stephens RG, Kogon SL, Jarvis AM. A study of the reasons for tooth extraction in a Canadian population sample. J Can Dent Assoc 1991: 57: 501504. 131. Tabor HK, Risch NJ, Myers RM. Candidate-gene approaches for studying complex genetic traits: practical considerations. Nat Rev Genet 2002: 3: 391397. 132. Taylor GW. Glycaemic control and alveolar bone loss progression in type 2 diabetes. Ann Periodontol 1998: 3: 30. 133. Temple DH, Larsen CS. Dental caries prevalence as evidence for agriculture and subsistence variation during the Yayoi period in prehistoric Japan: biocultural interpretations of an economy in transition. Am J Phys Anthropol 2007: 134: 501512. 134. Thomason JM, Heydecke G, Feine JS, Ellis JS. How do patients perceive the benet of reconstructive dentistry

135.

136.

137. 138.

139.

140.

141.

142.

143. 144.

145. 146. 147. 148. 149.

with regard to oral health-related quality of life and patient satisfaction? A systematic review Clin Oral Implants Res 2007: 18 (Suppl. 3): 168188. Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: ndings from NHANES III. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol 2000: 71: 743751. Tonetti MS. Periodontitis and risk for atherosclerosis: an update on intervention trials. J Clin Periodontol 2009: 36(Suppl 10): 1519. Tonetti MS, Mombelli A. Early-onset periodontitis. Ann Periodontol 1999: 4: 3953. Toomes C, James J, Wood AJ, Wu CL, McCormick D, Lench N, Hewitt C, Moynihan L, Roberts E, Woods CG, Markham A, Wong M, Widmer R, Ghaffar KA, Pemberton M, Hussein IR, Temtamy SA, Davies R, Read AP, Sloan P, Dixon MJ, Thakker NS. Loss-of-function mutations in the cathepsin C gene result in periodontal disease and palmoplantar keratosis. Nat Genet 1999: 23: 421424. Torabinejad M, Anderson P, Bader J, Brown LJ, Chen LH, Goodacre CJ, Kattadiyil MT, Kutsenko D, Lozada J, Patel R, Petersen F, Puterman I, White SN. Outcomes of root canal treatment and restoration, implant-supported single crowns, xed partial dentures, and extraction without replacement: a systematic review. J Prosthet Dent 2007: 98: 285311. Trovik TA, Klock KS, Haugejorden O. Trends in reasons for tooth extractions in Norway from 1968 to 1998. Acta Odontol Scand 2000: 58: 8996. Tsai C, Hayes C, Taylor GW. Glycemic control of type 2 diabetes and severe periodontal disease in the US adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2002: 30: 182192. Ulivieri S, Oliveri G, Filosomi G. Brain abscess following dental procedures. Case report. Minerva Stomatol 2007: 56: 303305. Vieira F, Allen SM, Stocks RM, Thompson JW. Deep neck infection. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2008: 41: 459483, vii. Wagner KW, Schon R, Schumacher M, Schmelzeisen R, Schulze D. Case report: brain and liver abscesses caused by oral infection with Streptococcus intermedius. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006: 102: e21e23. WHO. http://www.dent.niigata-u.ac.jp/prevent/perio/ contents.html. 2009. WHO. http://www.whocollab.od.mah.se/countriesalphab. html. Geneva 2009 WHO. http://www.whocollab.od.mah.se/expl/globalcar1. html. 2009. WHO. http://www.whocollab.od.mah.se/expl/regions.html. 2009. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour LM, Levison M, Bolger A, Cabell CH, Takahashi M, Baltimore RS, Newburger JW, Strom BL, Tani LY, Gerber M, Bonow RO, Pallasch T, Shulman ST, Rowley AH, Burns JC, Ferrieri P, Gardner T, Goff D, Durack DTAmerican Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Prevention of infective

17

Beikler & Flemmig

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation 2007: 116: 17361754. 150. Wimmer G, Pihlstrom BL. A critical assessment of adverse pregnancy outcome and periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 2008: 35: 380397. B, Freesmeyer 151. Wolfart S, Heydecke G, Luthardt RG, Marre stmann B, Mundt T, Pospiech P, Jahn F, WB, Stark H, Wo

dler M, Aggstaller H, Talebpur F, Busche E, Bell Gitt I, Scha M. Effects of prosthetic treatment for shortened dental arches on oral health-related quality of life, self-reports of pain and jaw disability: results from the pilot-phase of a randomized multicentre trial. J Oral Rehabil 2005: 32: 815 822. 152. Yoshida Y, Hatanaka Y, Imaki M, Ogawa Y, Miyatani S, Tanada S. Epidemiological study on improving the QOL and oral conditions of the aged Part 1: the relationship between the status of tooth preservation and QOL. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Human Sci 2001: 20: 363368. 153. Zitzmann NU, Berglundh T. Denition and prevalence of peri-implant diseases. J Clin Periodontol 2008: 35: 286291.

18

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- 3 DeruptionpathalveolarcleftsDocumento7 pagine3 DeruptionpathalveolarcleftsorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Screw Retained Abutment LevelDocumento4 pagineScrew Retained Abutment LevelorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- MICHELOTTI HomeExerciseRegimenesForTheManagmentOfNonSpecificTMDDocumento7 pagineMICHELOTTI HomeExerciseRegimenesForTheManagmentOfNonSpecificTMDorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Specialties 01Documento3 pagineSpecialties 01orthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- ASDA White Paper Final-NewcombDocumento20 pagineASDA White Paper Final-NewcomborthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- MedulloblastomaDocumento24 pagineMedulloblastomaAina Fe SalemNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Screw Retained Implant LevelDocumento4 pagineScrew Retained Implant LevelorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Comparison Chart For Digital CamerasDocumento1 paginaComparison Chart For Digital CamerasorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- 2011 Awards Scholarships and Fellowships ApplicationDocumento1 pagina2011 Awards Scholarships and Fellowships ApplicationorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- 2014 Written Examination Guide ABODocumento17 pagine2014 Written Examination Guide ABOorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Treatment Effects of Invisalign Orthodontic AlignersDocumento6 pagineThe Treatment Effects of Invisalign Orthodontic AlignersorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Philadelphia Philadelphia International Airport: Airport and Sports ComplexDocumento1 paginaPhiladelphia Philadelphia International Airport: Airport and Sports ComplexorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 Combined CANDIDATE ManualDocumento121 pagine2014 Combined CANDIDATE ManualorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Dental Rule 150Documento3 pagineDental Rule 150orthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Kozlowski - Clinical Efficiency ARTICLEDocumento3 pagineKozlowski - Clinical Efficiency ARTICLEorthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Ormco InstrumentsDocumento44 pagineOrmco Instrumentsorthodontistinthemaking100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Prodigy ClipComparison r5Documento1 paginaProdigy ClipComparison r5orthodontistinthemakingNessuna valutazione finora

- The History and Development of Self-LigatingDocumento14 pagineThe History and Development of Self-LigatingLamar Mohamed100% (1)

- Hero3 Um Black Eng Revd WebDocumento67 pagineHero3 Um Black Eng Revd WebSyafiq IshakNessuna valutazione finora

- Structural and Dynamic Bases of Hand Surgery by Eduardo Zancolli 1969Documento1 paginaStructural and Dynamic Bases of Hand Surgery by Eduardo Zancolli 1969khox0% (1)

- Bell 2015Documento5 pagineBell 2015Afien MuktiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Belo. Nur 192. Session 13 LecDocumento3 pagineBelo. Nur 192. Session 13 LecTam BeloNessuna valutazione finora

- Benign - Malignant Ovarian TumorsDocumento34 pagineBenign - Malignant Ovarian TumorsAhmed AyasrahNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To HemostasisDocumento16 pagineIntroduction To HemostasisRaiza RuizNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Dental Management in Hypertensive PatientsDocumento9 pagineDental Management in Hypertensive PatientsIJAERS JOURNALNessuna valutazione finora

- Maternal Care and ServicesDocumento35 pagineMaternal Care and ServicesAaron ConstantinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lampi DragerDocumento68 pagineLampi DragerAlin Mircea PatrascuNessuna valutazione finora

- MestastaseDocumento10 pagineMestastaseCahyono YudiantoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Gastric CancerDocumento31 pagineGastric CancerHarleen KaurNessuna valutazione finora

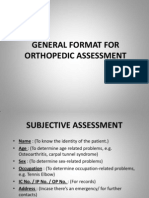

- General Format For Orthopedic AssessmentDocumento27 pagineGeneral Format For Orthopedic AssessmentMegha Patani100% (7)

- Onco-Critical Care An Evidence-Based ApproachDocumento539 pagineOnco-Critical Care An Evidence-Based ApproachZuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Pcap - PathophysiologyDocumento4 paginePcap - PathophysiologyAyla Mar100% (1)

- Determinants of HealthDocumento29 pagineDeterminants of HealthMayom Mabuong92% (12)

- Komunikasi Asuhan Pasien - KARS - 2019Documento93 pagineKomunikasi Asuhan Pasien - KARS - 2019Yudi Tubagja SiregarNessuna valutazione finora

- Fixation of Mandibular Fractures With 2.0 MM MiniplatesDocumento7 pagineFixation of Mandibular Fractures With 2.0 MM MiniplatesRajan KarmakarNessuna valutazione finora

- PartografDocumento31 paginePartografrovi wilmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit One Vocabulary: 'prɔvidәntDocumento53 pagineUnit One Vocabulary: 'prɔvidәntKhanh Chi NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Devoir de Synthèse N°2 2011 2012 (Lycée Ali Bourguiba Bembla)Documento4 pagineDevoir de Synthèse N°2 2011 2012 (Lycée Ali Bourguiba Bembla)ferchichi halimaNessuna valutazione finora

- tmpD824 TMPDocumento12 paginetmpD824 TMPFrontiersNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Elementary Reading Comprehension Test 02 PDFDocumento4 pagineElementary Reading Comprehension Test 02 PDFroxanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rajasekhar2021 Article TheUsefulnessOfGenelynEmbalminDocumento4 pagineRajasekhar2021 Article TheUsefulnessOfGenelynEmbalminyordin deontaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Pediatrics PDFDocumento208 pagineThe Little Book of Pediatrics PDFPaulo GouveiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Status Asthmaticus Case StudyDocumento18 pagineStatus Asthmaticus Case Studygeorgeloto12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Konsensus IBDDocumento15 pagineKonsensus IBDTaufikNessuna valutazione finora

- Tetagam P: Human Tetanus Immunoglobulin IM 250 IUDocumento25 pagineTetagam P: Human Tetanus Immunoglobulin IM 250 IUhamilton lowisNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiple Pregnancy: Prof Uma SinghDocumento53 pagineMultiple Pregnancy: Prof Uma Singhpok yeahNessuna valutazione finora

- Sensus Harian TGL 02 Maret 2022...........Documento121 pagineSensus Harian TGL 02 Maret 2022...........Ruhut Putra SinuratNessuna valutazione finora

- Pre Op NCPDocumento1 paginaPre Op NCPJoshua Kelly0% (2)

- International Journal of Surgery Open: Amir Forouzanfar, Jonathan Smith, Keith S. ChappleDocumento3 pagineInternational Journal of Surgery Open: Amir Forouzanfar, Jonathan Smith, Keith S. ChappleSiti Fildzah NadhilahNessuna valutazione finora

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDa EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeValutazione: 2 su 5 stelle2/5 (1)