Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Coalition Ministerial Responsibility

Caricato da

Subrahmanyam SripadaCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Coalition Ministerial Responsibility

Caricato da

Subrahmanyam SripadaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1) BACKGROUND: For the first 30 years since Independence, or for 25 years since the first gener al elections in 1952,

the country had experienced only single-party governance a t the centre. In the 1977 general elections post-Emergency, the Centre had its first experienc e of multi-party governance. This did not last long. In the 1980 and 1984 electi ons, a single party was again given the mandate, in the latter with the largest majority that a single party ever had in the Lok Sabha. But that, ironically, wa s also the end of single-party majority, though from 1991 to 1996 a single party was in power, but without a parliamentary majority. Hence, in a way, since the 1989 general elections the country has been experimenting with various shades of multi-party governance. The 13th general elections of 1999 were the first to bring to power a pre-electi on multi-party coalition that stayed on for its full term of five years. The 200 4 general elections saw yet another step towards coalition governance with two m ajor coalitions fighting to come to power. Are coalitions inherently unstable? The experience of West Bengal in the past th ree decades shows that coalition governments can be as stable as single-party go vernments. And Kerala's experience indicates that two coalitions can emerge over a period, providing the possibilities of stability and periodic change. 2) COLLECTIVE RESPONSIBILITY: But a criticism of some substance is that in a parliamentary system of governanc e, coalition regimes tend to weaken the basic principle of the collective respon sibility of the Cabinet (the executive wing) to Parliament (the legislative wing ) because Ministers of the Cabinet turn out to be the nominees of their parties, and not selected by the Prime Minister. The problem becomes more acute when the coalition consists of a large number of small parties as is often the case. The issue is not only the weakening of colle ctive responsibility: often it becomes the basis of absence of ministerial respo nsibility itself. India is a vast and vastly diverse country and that it is unnatural to expect a single political party to accommodate such diversity of language, caste and soci al customs, economic conditions and much more. These factors found their reflect ion in the country's political processes from the early days of Independence. At the level of the States there has always been a diversity of political partie s, and while coalition governments emerged at the Centre only some three decades after Independence, coalitions started functioning in the States from day one. The very first general elections held according to the new Constitution and on t he basis of universal adult franchise resulted in a non-Congress coalition gover nment in what was then PEPSU (Patiala and East Punjab States' Union). In two other States, Madras (then consisting of most of today's Tamil Nadu, parts of what subsequently became Andhra Pradesh, and the Malabar region of today's Kera la) and Travancore-Cochin, the Congress, which did not win a majority of seats i n the respective State Assemblies, formed governments with the support of minor parties. And, of course, after the 1967 elections many States came to have coali tion governments. The leaders of the powerful regional parties none of them had even 50 members in the Lok Sabha with a strength of 543 seized the opportunity. They prevented the larger of the two national parties (BJP) from coming to power, anointed one amo ng themselves (then a Chief Minister in one of the States) as the Prime Minister to head a coalition called the United Front, and forced the Congress to extend

support from outside. Indeed, while the United Front was in power at the Centre from June 1996 to February 1998, the country had something of a Chief Ministers' Ra j. That was a step forward in this country, which is a federation of States, but it was a learning process too. For, the regional leaders soon realised that a fede ration of States as such cannot function at the Centre. The Centre needed one la rge party with a notional All-India character. Hence when the United Front collaps ed in 1998 and the BJP emerged as the largest single party, but without a majori ty of its own, in subsequent elections the same year, some regional leaders were more than willing to align themselves with that party, which they had shunned t wo years earlier, and become partners in a post-election coalition. Regionalisation can be considered a positive aspect only if it enables the gover nments and, in fact, politics too, to respond to the true aspirations of the peo ple at large. The Akali Dal in Punjab has been based on religious and cultural considerations. The Telugu Desam Party in Andhra Pradesh emerged to protect regional aspiration s and sentiments. The Samajwadi Party in Uttar Pradesh and the Rashtriya Janata Dal in Bihar arose in response to Mandalisation. The Bahujan Samajwadi Party in Ut tar Pradesh was meant initially to champion the cause of Dalits. The Communist P arty of India (Marxist) and the Communist Party of India, mainly in West Bengal and Kerala, have strong ideological moorings. Such diversity is nothing unnatural given the diversity and variety of the count ry. The crucial question is whether regional parties, while being committed to t heir special concerns, are using politics to satisfy the basic needs and promote the basic rights of the people of the region. A major transformation of the pol ity of the country is necessary for this process, which must involve all politic al parties, national and regional. The question is whether parties will become i nclusive in terms of fulfilling the basic needs of all people, responding to the human rights of all people. This is indeed a tall order.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Carpio V Executive SecretaryDocumento8 pagineCarpio V Executive SecretaryIsmael MolinaNessuna valutazione finora

- In The Court of Appeal of Alberta: Restriction On PublicationDocumento24 pagineIn The Court of Appeal of Alberta: Restriction On PublicationCTV CalgaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Engineers Code of EthicsDocumento6 pagineEngineers Code of EthicsNymi D621Nessuna valutazione finora

- CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Subex LimitedDocumento4 pagineCORPORATE GOVERNANCE Subex LimitedBhawana SaloneNessuna valutazione finora

- Crime TheoryDocumento9 pagineCrime TheoryHillary OmondiNessuna valutazione finora

- Formative Assessment III Class 12Documento1 paginaFormative Assessment III Class 12ashverya agrawalNessuna valutazione finora

- CCA Group ActivityDocumento5 pagineCCA Group ActivityShruti PawarNessuna valutazione finora

- Rural Litigation and Entitlement KendraDocumento8 pagineRural Litigation and Entitlement KendraPrakhar Maheshwari100% (1)

- Iskander Mirza (Auto-Saved)Documento14 pagineIskander Mirza (Auto-Saved)ahraaraamirNessuna valutazione finora

- Mahatma Gandhi: Brief ChronologyDocumento7 pagineMahatma Gandhi: Brief ChronologyBraj KishorNessuna valutazione finora

- NCJ To ALLP 6 Tickets (Ramesh)Documento2 pagineNCJ To ALLP 6 Tickets (Ramesh)sri mathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Concept Note CLADHO - EU - Fiscal TransparencyDocumento13 pagineConcept Note CLADHO - EU - Fiscal TransparencyKabera GodfreyNessuna valutazione finora

- At.2507 Understanding The Entity and Its EnvironmentDocumento26 pagineAt.2507 Understanding The Entity and Its Environmentawesome bloggersNessuna valutazione finora

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Public Attorney's OfficeDocumento7 paginePlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Public Attorney's OfficeJose Edmundo DayotNessuna valutazione finora

- Zodiac Killer Thesis StatementDocumento4 pagineZodiac Killer Thesis Statementaprilfordsavannah100% (2)

- Armovit Vs CADocumento5 pagineArmovit Vs CAWEDDANEVER CORNELNessuna valutazione finora

- United States District Court Middle District of Florida Orlando DivisionDocumento12 pagineUnited States District Court Middle District of Florida Orlando DivisionJ Rohrlich100% (1)

- Neurofeedback in ADHDDocumento172 pagineNeurofeedback in ADHDThomas Marti100% (1)

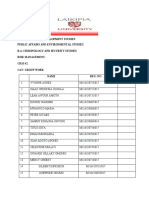

- Tos (Summer Sem 2020-2021)Documento1 paginaTos (Summer Sem 2020-2021)Sarah AgonNessuna valutazione finora

- Answers Module 1 EducareDocumento1 paginaAnswers Module 1 EducareJonathan SpinksNessuna valutazione finora

- SEC-sets-deadline-for-filing-of-annual-reports - For 2019Documento3 pagineSEC-sets-deadline-for-filing-of-annual-reports - For 2019Aya PulidoNessuna valutazione finora

- An Ineluctable Political Destiny Communism Reform Marketization and Corruption in Post Mao China Forest C Sun Full ChapterDocumento33 pagineAn Ineluctable Political Destiny Communism Reform Marketization and Corruption in Post Mao China Forest C Sun Full Chaptersandra.gonzalez152100% (5)

- LSE Uncon OfferDocumento3 pagineLSE Uncon Offer黄涛Nessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 144214 - Villareal v. RamirezDocumento5 pagineG.R. No. 144214 - Villareal v. RamirezKimmy May Codilla-AmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Art. 177 - Gigantoni vs. People of The Phil.Documento1 paginaArt. 177 - Gigantoni vs. People of The Phil.Ethan KurbyNessuna valutazione finora

- Vận Tải Bảo HiểmDocumento6 pagineVận Tải Bảo HiểmMinh ThưNessuna valutazione finora

- New York State Dedicated Highway and Bridge Trust Fund CrossroadsDocumento18 pagineNew York State Dedicated Highway and Bridge Trust Fund CrossroadsNews10NBCNessuna valutazione finora

- 23-719 Bsac American Historians FinalDocumento44 pagine23-719 Bsac American Historians FinalAaron Parnas100% (3)

- Gabriel Feltran. "The Revolution We Are Living"Documento9 pagineGabriel Feltran. "The Revolution We Are Living"Marcos Magalhães Rosa100% (1)

- Correctional Administration in India 7th SemDocumento5 pagineCorrectional Administration in India 7th SemAayushi PriyaNessuna valutazione finora