Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Alchin - Justified True Belief

Caricato da

Cecilia ChowDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

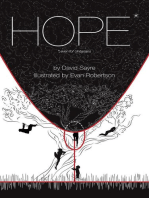

Alchin - Justified True Belief

Caricato da

Cecilia ChowCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1

('--

0

D

0

511.1111 teach you wh.1t knvw!ec(s-e i;;!' When

you k1l0W.1 thins, tv recLl,S'nisc tll.lt YLJlI

knL)W it; .1nd when VUlt du IlLlt kttL1W.I

thins- to recognise th;t yvu. do not knLlw it.

rhJt l:> knuwledSe.

COI1jllliu:;

Whu-:, there' IS

shout:tng chere no

CruC" kmJwledge.

Lt'lllldrd(J dd Vi/h'i

0)

NOTHING IN ALL THE

WORLD IS MORE

DANGEROUS THAN

SINCERE IGNORANCE

AND CONSCIENTIOUS

STUPIDITY.

Mediocre minds usually

dismiss anything which

reaches beyond their Own

understanding.

c

--

C

CD

S

CD

L-

eu

eu

..c

5

l'vltlflill Lwita

Education is learning what you

didn't even know you didn't know.

Daniel J. Boorscin

FnlJh'ois til! L7 RUc/llirJlICdld

It i::; very for a llIall to

talk ahout what he does not

under:;tand: as as he

HIlIlel"stands that he does not

understand it.

C. K. CheSli::rton

Those wh() are CVl1vtl1ced they have a

mQ'lOPQly Qn The TrL(th always Feel that

they are Qnly saving the WQrld when they

slaughter the heretics.

A very popular

error - baving the

courage of one's

convictions;

rather it is a

matter of having

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr

THERE ARE MANY WHO

KNOW MANY THINGS,

YET ARE LACKING IN

WISDOM.

Democrirus

the courage for an

attack upon one's

convictions.

Anon

The most imporc.an-c truths are

likely to be which ...

socie"ty at that "time least wants

to hear.

vV'. H. Auden

Never assume the

obvious is true.

The criterion of truth is that it works even if

nobody is prepared to acknowledge it.

William Safire

Ludwig von Mises

c

c

h"

i

,

Ai m S By the end ofthis chapter you should:

understand that, perhaps contrary to what you have so far found

in your formal education, certainty and truth are not easily found

recognise that there are many dubious pieces of 'knowledge'

available and that even the word of a world authority is no

guarantee of truth

understand that 'certainty' is a matter of degree and that some

opinions are better than others

be able to give at least an initial definition of 'knowledge' and

distinguish between 'knowledge' and 'belief'

be able to list and give a simple critique of different reasons for

saying that you 'know' something

be able to discuss how these different reasons relate to the

standard academic subjects.

_____ J.l1 o...IJt..LlrOJ::Lucli.oD

You have probably been in full-time education for a number of

years, and in that time you have acquired a vast amount of

knowledge. With the help of your teachers and your textbooks.

the ;'umber of facts you know and the depth of your knowledge

are probably alnazing. What is more, you are learning more and

more. and will probably go on to do so for several more years. In

the sciences, for example, many of you will know about Einstein's

theories. Einstein is widely regarded as one of the greatest

geniuses of all time. and yet the physicists among you will be

writing about his ideas in your exams. In English literarure. many

of you will be able to analyse and discuss Shakespeare. possibly

the greatest English playwright the world has ever seen and will

ever see. The same goes for any Other subject; you will be studying

ideas that only thinkers of great genius could develop.

\Nhen you scale that up to all the people alive today. you realise

that the amount of knowledge out there is lTuly staggering. \Vhat

is more, you have access to so much of it. You wam to know vvhal

ill1imals \vere walking the Earth two hundred million years Jgo?

Look il up in a book. You Want 10 know \'Vhat it's like in

Antarctica in the middle of \vinter? \Natch a documentary. And

il'S getting better all the time - with newspapers. magazines. TV

the. internet. you can find out all about the world without

leaving the comfort of your own home. And what could be mure

reliable than journalism and the internet?

\Vell. recent headlines thaI hJve been seen in one. adminedly

less IhJn il\uslrious. newspaper include '\tv'oman Eaten by Fur

COJ!!' and 'Alien Base Found on Dark Side {)[ Moon!'. The lauer

is especially interesting, as vvhen it \yas poiJ1led OUl that NASA

piclUres sho\ved no such base. the nt'\-vspaper ran all 'Alien Base

Disappears!' story. The iJ1lerllet, too. is hardly a

totally lruslwonhy source of information -'just look for the 'Elvis

is alive and well and working as a plumber in Bolivia' websites!

So can we lrllSl the information that \-\'e have?

J can imagine wh,11 you art' at this stage: that these art'

stupid eXJmples. Ollly rl'ally gullible people would believe siories

i

J

as ridiculous as these, ilnd nobody with ,lilY sellse w(1uld 111.1kl'

errors as obvious. So now consider the following predictions.

They are slightly different from the ne\NSpapl'r he;:H.llinl's in th,ll

they Jre Jil claims about the fUlLlre, but they still lell us

something about the possibility of error.

That! is JlO likelihood ehar humalls l"t'ili tTl'f {dP (lIe POWtT ,l! rlit' 1/{0111.

Roben !v1illikan, Nobel Prize vVinner in Physics (1923)

The atom bomb will neva!:fo ojf dl1d I sped/.:. ,IS III! t'XPl'fL

AdmirJl vY. Leahy, Jdvisor to the US President (1945)

/ eliink rhue wi!! be a ~ v o r d marker for five LOI11Plf{t'rs.

Thonl<lS vYatson. founder of IBivl (1958)

By 2000 womt'n will we'l1r panes. !11e'Jl wii! We'dr skirrs. b{lr/t St'X!!S will

go bare-Lllt'Sh'd (we'dtiza permiuing) dJld c/<J{hes will be .\'t'e-tiznJ/{!:fh,

Rudi Gernreitch, American fashion expert (1970)

Tilt' {mane! wilt /lever lake' of!

Bill Gales. founder of !'vUcrosofr { 1988}

So it isn't just stupid people who get things wrong. Perhaps there Jre

errors in what you are told every day. even in what you are reading

now. It could be that what you [earn in school isn't towlly correct.

So when I said that you have a lot of knowledge, maybe I should

have been more carefuL How much of what you know is true?

A Identify something that you have been told, which you believed at

the time but which you now recognise is false. How did you find out

the truth?

B Think of some things about which you are absolutely certain. Is

anyone else certain about them, too?

C What is the difference between 'I am certain that .. .' and 'It is

certain that _ . . ?'

So when and how do you know if something is true? In relation to

your studies, which of your subjects is the mOst reliable, and why?

Does this reliability come at a cost? Answering these questions is

the central theme of this book, and sometimes the answers can be

quite surprising; they can force us to look at the world in a different

way. As a brief example, let's consider how much we know in light

of how long we have been around. Those of you who study history

may sometimes feel overwhelmed at the massive length of human

history. Geographers often comment how the impact of humans

can be felt all over the world, even in the remotest places. These are

both very valid perspectives. We humans dominate the Earth. In

many ways. we are the supremely powerful species on Earth at the

moment - there's no doubt about that.

But let's look at it slightly differently. Suppose you took the

whole history of the Universe and compressed it into one year.

(The year has been constructed on current estimates that the

Universe is 15 billion years old; that the Earth is 4.55 billion years

old; that humans developed around two million years ago. These

figures are controversial and almost certainly wrong, but we

don't know by how much! So take this example in the spirit in

which it is meant!) So now it is 12.00p.m .. I January. and the

Universe began exactly one year ago. How long would we have

c

been around for? Let's examine (he cosmic calendar.

Current theory suggests that our galaxy formed on 1 May. It

took another [our months, 10 9 September, until our solar system

appeared. A few days later. the Earth was formed. around

14 September. After life begins on 25 September, it may seem like

things are speeding up. bUl it then takes until 12 November for

the oldest photosynthetic plants to develop. and it isn't until

I December that there is a significant quantity of oxygen in the

atmosphere. So [or the first eight-and-a-half months. there was

no Earth. and even then for another two-and-a-half months

there was no conceivable way for humans. had they been

around, to survive. But at least now we are beginning to

approach human history ...

Although there was oxygen in the atmosphere. fish did not

develop until 19 December; trees followed soon after on

23 December. and the first dinosaurs turned up on 24 December.

Mammals arrived on 26 December. and had to live with the

dinosaurs until 28 December when it seems that a massive comet

struck the Earth. causing major climatic change. The dinosaurs,

unable to cope with this. died out. and the age of the mammals

started. Humans appeared on 3 I December. All of human history.

therefore. happened on the last day of the year. Well. at least we

have a day (remember that the dinosaurs had [our!). Or do we?

In fact. probably not. Humans developed rather late in the day.

around IO.50p.m. Current belief is that Peking Man first used fire

in a controlled way at 11.46p.m., and at 11.59p.m. cave paintings

started being created in Europe. Things happen in a rush now,

with agriculture transforming the human way of life at 11.59.10.

and the alphabet allowing detailed communication through

generarions at 11.59.51. The modern calendar began al 11.59.56

with the binh of Christ. The great Mayan civilisation and Chinese

Sung Dynasty came and weIll at 11.59.58. and ant' second later,

al 11.59.59, the modern technological world was born with the

Renaissance and Industrial Revolution.

On the cosmic scale, therefore. it is only in the last fraction of a

sl'cond. on the last day in the entire year that an'}lone alive today

has existed. that you were born. Most people feel this to be

profoundly humbling. And vvhere dot'S it leave humans' feelings

of grandeur, sense of power and Sense of cenaiJ1lY?

A What is the humans' place in the Universe? How likely is it that

humans have found out any profound truths about the Universe?

B What are humankind's greatest successes?

C Does it really matter how long we have been around?

S01lll' people think that lhe cosmic calendar anJlogy cJ:\Is into

qUl'stioll our ccrtaiJ1lies and our claims 10 knowledge. Cenainly.

il aler!.s us to tht' fact that our POiIll of view is jusl one. perhJjb

vl'ry rtn:1lI ilnd very moot'st. perspective J:nd it gives us good

rl'JSllil 10 Jpproach grand clJims to knowledge with SOl1l<:

hllmility. Howevl'f. 'Nt' il<lve skirted Jround lilt' subject for l(lng

l'lwugh. V'Ve 1l1..'ed t(l find oul whJI knowledgl' JctuJlIy is hl'iorl'

Wl' begin propl'l'ly In qUl'stion il.

,

I

I

i

!

,

!

LJ

, o.

1

I

I

>=

's:

i",

icc

,'"

I ....

I",

'J::

Is:

,-

I

This may seem like a ridiculous question. 'vVe know Wh,ll

knowledge ('5. don't we? WelL maybe, but explaining it may

prove to be i.1 little tricky. Le(s think about <1 couple or eX<llllpks

where we use [he word 'know', 'vVhJt do you l1l<lke of thl' person

who claims that [hey know that (he Sun is pulled JCross thl' sky

by six chameleon-like horses who blend into the sky so well thal

they Jre invisible: Or about my knowledge that [ am. in fJel. Lhe

secret hybrid product of an alien/human experimelH? Can wt'

really say we 'know' such things?

Most people would say that these beliefs are nut knowledge

because they are not true. We wouldn't say that people knew the

Earth was flat; we would say that they believeu it. but that they

were proven wrong. Similarly, children cannQ( know, but can

only believe, that Santa Claus is coming to town. There is ..1

difference between belief anu knowledge.

A We have suggested that you can believe something without knowing

it. Is it possible to know something without believing -it?

B Is knowledge the same as true belief? Can you imagine a case where

someone beHeves something which is true, but where we would not

say that she knows it?

C One night my watch broke at 11.51, but I didn't realise. I was

asleep at the time, and when I woke up I just put the watch on

without looking at it. The next time I looked at it, it was, by chance,

11.51.1 believed it was 11.51, and it was, in fact, 11.51, So did I

know it? If not, why not?

In answer to question C, mOSt people would say that I did nOt

know it was 11.51. and that it was just a fluke. But this means

something is wrong with saying knowledge is true belief. I

believed it was 11. 51. and it was true that it was 11.51. So why

didn't I know it was 11.51?

Let's consider another example. Imagine that you find a

lost manuscript detailing a conversation between two scholars,

Joseph and Daniel, from the Middle Ages. The text starts;

'JOSeph! I have made a great discovery! The Earrh is round, not flat as

everyone believes!'

Immediately your eyes light up! You have a fantastic new

historical document. Excitedly, you read on:

'Whar rubbish Daniel. Anyone can see that the Earrh is flat. The Greeks

may have written something about a round Earrh, but we have moved on

since chen. We know it is flat. Why are you saying this?'

'I have compelling evidence: can deny it. '

'Go on chen, tell me what brilliant discovery YOll have made. '

You are breathless with excitement - what evidence has Daniel

found? Will he talk about the shadow cast by the Earth on the

moon, or about ships vanishing on [he horizon?

c

'Its wonder lies in its ve1Y simplicity! Take off your shoes and /o(Jk at your

feet - they are wnlcd on the bocrom! Your Jeer have arches! Whar is the

reaSOl1 for char? It can only be that in your childhood. when you H-'alked

around shoes. your fcer were moulded to rhe shape oj [he round

Earrh! '

Deflated and disappointed. you realise that Daniel did not know

the Earth was round at all! He believed it. and it is true, but he

didn't know it because his reasons were n01 adequate - his belief

was unjustified. In the case of my faulty watch (above), I did not

know that it was 11.51 because my justification would have

rested on a false assumption - that my watch was working. So

perhaps we may define knowledge as justified, true belief.

A Does the 'justified, true belief' definition fit our understanding of the

term 'knowledge', or does it wrongly include or exclude anything?

That is, can you think of a situation where either:

someone might have justified, true belief but we wouldn't say

that they knew something

someone did not have justified, true belief but we would say they

knew something?

So is the 'justified, true belief' definition absolutely correct? It has

been suggested that to define knowledge like this is not very

helpful- and for a very simple reason. If we claim to know

something then we believe it. and we believe it to be justified and

to be true. But how do we know if it is really justified andlor

really true? You should see the problem here - we are trying to

define knowledge in terms of justificalion and truth, but we are

having to use the concept of knowledge in doing so! Our

definition has become circular, and ultimately unhelpful.

A Moliere once wrote that a sleeping potion worked by virtue of its

'dormitive faculty'" How is this related to what was said in the

previous paragraph?

B Can you find a solution to the problem that defining knowledge as

'justified, true belief' may be a circular definition?

If we Jpproach the issue in a dif!t'n:nt \Nay" then the

problem (If justification is nut as serious JS we Rather

than saying "Ihis is juslifi<:d' or "this is 11tH justifit:J", mJybe \Ne

sh()uld talk about the validity of lhe jllslifici1!illn - inr exampk,

'poor jtlslificJtit1n', justifiCJlinn' or 'l'xcelknl justification'

- il'Jding 10 'slronger' (lnd 'wl'Jke( forms of knowkdgt.

A What sort of justifications would lead to 'strong' knowledge or

'weak' knowledge?

B ReVisit the examples in this section and describe the validity of the

justifications, Is the 'knowledge' 'strong' or 'weak'?

C Which of your school subjects give you 'strong knowledge'? Which

give you 'weak knowledge'?

8

How do we proceed from here: 'yVc have beell arguing aboul [hl"

meaning of words for a little toO long (this is something thJt.

rightly or wrongly, philosophers are of len accused of dOing!).

Perhaps we need to start looking at examples of whJt we consider

to be knowledge. and see how we justify these clJims. So let us

take our tentative definition of 'justified, true belief' Jt face VJlut'

and, while we remain aware that it is a limited definition, let's

use it to set our the parameters of our inquiry. If knowledge is

justified, true belief then we must examine whitt we believe, how

we justify our beliefs and whether or not they are likely 10 be

true. Let's start with a simple question.

It is very easy to read, often in reputable newspapers, that news is

about facts, and opinions un those facts. Facts are disputable (for

example, we can argue about the number of computers sold in

lndia in (999) but there is a right and a wrong answer. Opinions

are rather different - you may hear it said that an opinion can

never be wrong because everybody is entitled to their own

opinion. The notion of freedom is sometimes interpreted as

meaning that anyone's opinion is as good as anyone else's.

This is actually pure nonsense. Suppose you are a keen runner.

but you break your leg in an accident. Your leg is put in plaster

for a month. and when the plaSter is removed you are keen to

start training straightaway. In my opinion. you should start

training immediately. and push yourself really hard. ignoring any

pain. until you are as fit as you were before the accident. In your

doctor's opinion. you should take things very slowly. and stop as

soon as you feel any pain.

Which opinion is better? Clearly. the one that is based on

reason and experience. This is the kind of opinion most important

to educated people. and the kind we will concentrate on in this

course. Most people would agree that some opinions are better

than others - the difficult thing is to decide how to tell a good

opinion from a bad one. In the case of the injured runner. it

seems reasonable to trust a doctor. as she will have better reasons

for her judgement than a lay person.

We might plausibly argue that there are three types of questions.

Questions that have one correct answer. Example: how many

atoms of hydrogen are there in a water molecule?

Questions that have many possible answers but which require

justification and reasoned judgements. Example: what is the

beSt way to tackle the developing world's debt problem?

Questions that have no correct answer but depend totally on

the' person answering the question. Example: which type of

chocolate tastes best?

Sometimes it is possible to argue about which category a question

falls into - for example. 'Is this painting good an?' Some people

might put it in the third category while some might choose the

second. If in doubt. it is worth assuming that it is a question

worthy of debate and exploring how a discussion develops. If it

o

turns out to be pure personal choice. with nothing to be said for

one side more than the other. then it will probably turn out to be

a short and boring discussion! If you find yourself coming up with

reasons that appeal to 'universal' intellectual standards. such as

clarity, consistency. honesty, factual accuracy and so on. then the

question is cenainly a 'type two' question.

It is the appeal to 'universal' intellectual standards which is

important. and it is these standards which we shall be looking at in

some detail. (Of CQurse, we might argue about 'universal' bUI 10

argue at all requires some agreement.) The standards mean that we

can at least try to make coherent intellectual progress towards a

well-reasoned and justified answer with even the hardest questions.

A Do you think three categories of question are enough? Are there

any others you could add?

B For each of the following questions, decide which of the three

categories of knowledge the answer fits into.

How many planets are there in the solar system?

Who is the Singaporean minister with responsibility for education?

When was the French Revolution?

Is it wrong to kill?

What is the colour of the nearest wall?

Does God exist?

Are you happy?

Is your teacher happy?

is one plus one always two?

Does violence on television contribute to violence in the

community?

Was Hitler a good leader?

Can a male doctor know more about childbirth than a mother of

ten children?

Is it possible to know something but be unable to say what it is

that you know?

Will science eventually tell us how and why the Universe started?

C Three categories may not really seem to do the variety of questions

justice. If we want to analyse different types of knowledge, it might

be helpful to be more specific. What categories might you divide

knowledge up into?

In Jlls\vering the questions above, you have begun to justify your

thinking. In one sense. this whole book is about justifying our

thoughts on various topics: about arguing for what we believe in.

Vve nalurJlly do this all the time - when we explain why we

wZ!111 to set' a panicular film, how we solved a maths problem. Of

the nature of our religiOUS beliefs. For such an important topiC it

is surprising that we lIsually spend so little time examining

v.."helher ur nUl our reasons are-Jctually good reasons, or if some

II

-,

g!

(!J,

I

!

I

I

I

i

I

I

types of reasons are bener than others. In fact. most of us i

probably don'\ I'Ven know the differcl1ltypes of reasons IhM \Nl' !

h ~ l V l . so this IllLlSt be ollr stJrting point. U

,.

0

Q

0

I-

<:l

OJ

:s:

OJ

a:

"

.1-

i

A

Below is a rather dubious list of things that I might claim to know,

and another list of reasons that I might give to support these pieces

of knowledge. Match the reasons to the claims.

Claims

I know that the sky is blue because

I can see it.

I know that 1 + 1 = 2.

I know that it is wicked to murder a

person.

I know that I have a fear of spiders.

1 know that I went out for a run

yesterday.

I know that what the doctor said is true.

I know that women are more emotional

than men.

I know exactly what God wants of me.

I know that I am going to Heaven.

I know that a lake is more beautiful

than a sewage works.

I know that [love my brother.

Reasons

Value judgement

Faith

Memory

Authority

Intuition

Revelation

Sense perception

Logic

Self-awareness

Common knowledge

Instinct

B Are there any other ways to justify things that we know?

C Are any of these ways of knowing really the same thing?

D Which of these do you think are the most reliable ways of finding

the truth? Justify your answer.

We can argue about the distinctions, differences anu overlaps

between the categories given here as there are several possible

ways to categorise knowledge. For our purposes, we will suggest

that sense perception and logic (orm two vital cJ.tegories. and

later on we shall see how they arise naturally from an

examination of everyday and academic knowledge.

We have seen that there may be good reasons to think carefully

about we claim to know; that knowledge is a multi-faceted

and complex concept and humans are only recent additions to

the Universe. What hope do we have for certainty and truth

when we are so Iin1ited? And yet. we seem to have made so

much progress. even in the shon time we have been around. Our

societies are radically different to those of any animals; we know

how the stars shine and we have the power to destroy the Earth.

So far we have even had the wisdom not to! Have we overplayed

the weaknesses of humankind?

Perhaps in our quest for truth we should be a little more

positive and look at what we do know rather than what we do

nor. iY\avbe we should IlJrn OUf attention [Q what seems [Q be the

model for certainty in today's world - the narufal

sciences.

,

e

c

At this stage, any text that takes a thoughtful, reflective and wide-

ranging approach to knowledge will be very helpful. Excellent, short

and accessible essays on topics as diverse as propaganda, art, Santa

Claus, God and truth can be found in Martin Gardner's Order and

Surprise (Oxford University Press, 1983) and The Whys of a $crivening

Philosopher (Oxford University Press, 1985). For a more philosophical

but delightfully readable and very short introduction, you might try

Thomas Nagel's What Does It All Mean? (Oxford University Press,

1989). By the same author, Mortal Questions (Cambridge University

Press. 1979) is much more advanced but equally fascinating. For a

look at the whole concept of knowledge, it is hard to find a better

introduction than Stephen Gade Hetherington's Know/edge Puzzles

(Westview Press, 1996). In terms of relevant fiction, Robert Pirsig's Zen

and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (Bodley Head, 1974) takes an

unusual but compelling approach to some of the issues, and the

dazzling stories, essays and parables in Jorge Luis Borges' Labyrinths

(Penguin, 1964) defy description, providing a unique and paradoxical

window on the everyday world.

""

,gl

~

~

~

~

"-I

!

i

11 i

--'

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Edward O. Wilson - Letters To A Young Scientist-Liveright (2013)Documento171 pagineEdward O. Wilson - Letters To A Young Scientist-Liveright (2013)Leandro Mir100% (3)

- Hugh Nibley - Secrets of The Scriptures - The CreationDocumento62 pagineHugh Nibley - Secrets of The Scriptures - The CreationSyncOrSwim86% (7)

- Scientific Facts in The Bible PDFDocumento94 pagineScientific Facts in The Bible PDFRin Lavid78% (9)

- Telephonebetweenworlds1950 PDFDocumento129 pagineTelephonebetweenworlds1950 PDFVitor Moura Visoni100% (2)

- Is There A Creator Who Cares About YouDocumento94 pagineIs There A Creator Who Cares About YouraphaffNessuna valutazione finora

- Renault Nissan The Challenge of Sustaining ChangeDocumento12 pagineRenault Nissan The Challenge of Sustaining ChangeCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sky People (1970) by Brinsley Le Poer TrenchDocumento192 pagineThe Sky People (1970) by Brinsley Le Poer TrenchNur Agustinus100% (6)

- Arnett Kevin Mysteries Myths or MarvelsDocumento89 pagineArnett Kevin Mysteries Myths or Marvelsapi-3832144Nessuna valutazione finora

- Alexandre Koyre - From The Closed World To The Infinite Universe PDFDocumento241 pagineAlexandre Koyre - From The Closed World To The Infinite Universe PDFioan dumitrescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Cosmic Ships: Truth and Lies about UFOs, Other Humanities, and Our FutureDa EverandCosmic Ships: Truth and Lies about UFOs, Other Humanities, and Our FutureNessuna valutazione finora

- Edward O. Wilson Letters To A Young Scientist 2013Documento127 pagineEdward O. Wilson Letters To A Young Scientist 2013Diana RomeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Brain and Visual Perception 1 0195176189 PDFDocumento738 pagineBrain and Visual Perception 1 0195176189 PDFMaxim PopescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 2 Module Method of PhilosophizingDocumento3 pagineLesson 2 Module Method of PhilosophizingMikee MarceloNessuna valutazione finora

- Secrets of The ScripturesDocumento38 pagineSecrets of The ScripturesLeena Rogers100% (3)

- Humanology: A Scientist's Guide to Our Amazing ExistenceDa EverandHumanology: A Scientist's Guide to Our Amazing ExistenceNessuna valutazione finora

- Forgotten History: Captivating History Events that Have Been ForgottenDa EverandForgotten History: Captivating History Events that Have Been ForgottenNessuna valutazione finora

- Accelerating Personal EvolutionDocumento32 pagineAccelerating Personal EvolutionSean HsuNessuna valutazione finora

- Feynman ValueofscienceDocumento3 pagineFeynman ValueofscienceAjay DevNessuna valutazione finora

- Ted Hall's Playing.... DeckDocumento149 pagineTed Hall's Playing.... DeckReed BurkhartNessuna valutazione finora

- Ret. Librarian Patricia Konarski Tucson Pick: Transcript of Library of Congress Presentation Hosted by Carolyn BrownDocumento56 pagineRet. Librarian Patricia Konarski Tucson Pick: Transcript of Library of Congress Presentation Hosted by Carolyn BrownPatricia KonarskiNessuna valutazione finora

- Incompatible Truths - How Inept Modeling by Elites Subverted Western Religion and CultureDa EverandIncompatible Truths - How Inept Modeling by Elites Subverted Western Religion and CultureValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Lethbridge Part 1Documento21 pagineLethbridge Part 1Juan Miguel ll100% (1)

- Book-9 The Alien AgendaDocumento84 pagineBook-9 The Alien AgendaMirsuxNessuna valutazione finora

- Reason and LogicDocumento58 pagineReason and LogicPolis PortalNessuna valutazione finora

- Past, Present and Future: An Irreverent Treatment of HistoryDa EverandPast, Present and Future: An Irreverent Treatment of HistoryNessuna valutazione finora

- Alien Agenda Investigating The Extraterrestrial Presence Among Us by Jim Marrs Best Research PDFDocumento3 pagineAlien Agenda Investigating The Extraterrestrial Presence Among Us by Jim Marrs Best Research PDFPipirrin GonzalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay About JesusDocumento16 pagineEssay About JesusRoberta FranceschiniNessuna valutazione finora

- The Agenda by Beverly FoxDocumento46 pagineThe Agenda by Beverly FoxiamhappyoneNessuna valutazione finora

- We Don’T Dig Dinosaurs!: What Archaeologists Really Get up ToDa EverandWe Don’T Dig Dinosaurs!: What Archaeologists Really Get up ToNessuna valutazione finora

- Invader Moon: Who Brought Us the Moon and Why?Da EverandInvader Moon: Who Brought Us the Moon and Why?Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (4)

- Unidentified Submerged Objects and Underwater BasesDa EverandUnidentified Submerged Objects and Underwater BasesNessuna valutazione finora

- Alien Abductions (Or: Budd Hopkins, the Last Important Ufologist)Da EverandAlien Abductions (Or: Budd Hopkins, the Last Important Ufologist)Valutazione: 2 su 5 stelle2/5 (1)

- The Origins of Everything: Some True Stories for EliDa EverandThe Origins of Everything: Some True Stories for EliNessuna valutazione finora

- Flying Saucer Revelations - Michael X BartonDocumento64 pagineFlying Saucer Revelations - Michael X Bartonbirddogpan3g6t5100% (11)

- Mind Over Matter: Conversations with the CosmosDa EverandMind Over Matter: Conversations with the CosmosValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (9)

- Letters To A Young ScientistDocumento81 pagineLetters To A Young ScientistHana mae100% (1)

- Creation Science Evangelism 1998-Kent HovindDocumento101 pagineCreation Science Evangelism 1998-Kent Hovindsirdomino100% (1)

- Survival Manual: by Luc BodinDocumento29 pagineSurvival Manual: by Luc BodinJill Morgan César Sanou100% (1)

- Why Atheism Mark ThomasDocumento53 pagineWhy Atheism Mark ThomasKent Whitey JohnstonNessuna valutazione finora

- ISLAM The Natural Disposition For MankindDocumento34 pagineISLAM The Natural Disposition For MankindIslambase Admin100% (3)

- RichardDawkins NetDocumento106 pagineRichardDawkins NetTaufik Rahman MahlanNessuna valutazione finora

- Dr. Walter Bowman Russell: 1954 NewsletterDocumento8 pagineDr. Walter Bowman Russell: 1954 NewsletterfractalinkNessuna valutazione finora

- The Art of Being HumanDocumento8 pagineThe Art of Being HumanDahildu NeguNessuna valutazione finora

- Celestial Science - Max Steinberg - PDF For ComputersDocumento170 pagineCelestial Science - Max Steinberg - PDF For ComputersMax Steinberg100% (4)

- My Reality: As It Appears at the Beginning of the Twenty-First CenturyDa EverandMy Reality: As It Appears at the Beginning of the Twenty-First CenturyNessuna valutazione finora

- Urantia the Earth-The Origin of It All: Exploratory Journeys in the Urantia BookDa EverandUrantia the Earth-The Origin of It All: Exploratory Journeys in the Urantia BookValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- Giants by Glenn KimballDocumento20 pagineGiants by Glenn KimballBrian Ngenoh100% (1)

- Gods of Air and DarknessDocumento126 pagineGods of Air and DarknessBibliophilia7100% (3)

- Audition Repertoire PDFDocumento1 paginaAudition Repertoire PDFCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Mystères Limpides:: Time and Transformation in Debussy's Des Pas Sur La NeigeDocumento31 pagineMystères Limpides:: Time and Transformation in Debussy's Des Pas Sur La NeigeCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Rings Debussy 2008 PDFDocumento32 pagineRings Debussy 2008 PDFCecilia Chow100% (1)

- DMA Program Qualifying Examination ReportDocumento1 paginaDMA Program Qualifying Examination ReportCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Metra Schedule PDFDocumento2 pagineMetra Schedule PDFCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Betterment: General Investing GoalDocumento1 paginaBetterment: General Investing GoalCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Group X Spring ScheduleDocumento2 pagineGroup X Spring ScheduleCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Taubman TechniqueDocumento3 pagineTaubman TechniqueCecilia Chow100% (1)

- Desai, Mihir (2009) The Decentering of The Global FirmDocumento20 pagineDesai, Mihir (2009) The Decentering of The Global FirmCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Symphonic Band: Nformation For Riday ArchDocumento1 paginaSymphonic Band: Nformation For Riday ArchCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Keyboard Skills Observation FormDocumento1 paginaKeyboard Skills Observation FormCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- CPT ApplicationDocumento1 paginaCPT ApplicationCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Contract PDFDocumento4 pagineContract PDFCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Lined Portrait Letter CollegeDocumento1 paginaLined Portrait Letter CollegeCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- The Private Music LEssonDocumento4 pagineThe Private Music LEssonCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Group ClassesDocumento5 pagineGroup ClassesCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Private Lesson GuidelinesDocumento1 paginaPrivate Lesson GuidelinesCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of Student TeachingDocumento2 pagineEvaluation of Student TeachingCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Embraer in ChinaDocumento21 pagineEmbraer in ChinaCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- (7 Lenovo Entering Global Competition)Documento27 pagine(7 Lenovo Entering Global Competition)Cecilia Chow100% (1)

- WTO and OECD (2012) Trade in Value-Added Concepts, Methodologies and ChallengesDocumento28 pagineWTO and OECD (2012) Trade in Value-Added Concepts, Methodologies and ChallengesCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Huawei Enters The United StatesDocumento9 pagineHuawei Enters The United StatesCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal Data Form: Please Type or Print LegiblyDocumento1 paginaPersonal Data Form: Please Type or Print LegiblyCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Development Intern (3 Positions) : Chamber Music Festival and Institute - David Finckel Wu Han, Artistic DirectorsDocumento2 pagineDevelopment Intern (3 Positions) : Chamber Music Festival and Institute - David Finckel Wu Han, Artistic DirectorsCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Strt-460-Winter2019 Levy Final 19Documento10 pagineStrt-460-Winter2019 Levy Final 19Cecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Yang Dissertation 2014 PDFDocumento50 pagineYang Dissertation 2014 PDFCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Nutrition Guide: Limited Time Only & Featured OfferingsDocumento13 pagineNutrition Guide: Limited Time Only & Featured OfferingsCecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Correct The Citations 2018Documento2 pagineCorrect The Citations 2018Cecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Sep 25, 2018, 12:28Documento4 pagineSep 25, 2018, 12:28Cecilia ChowNessuna valutazione finora

- Martin Mahner and Mario Bunge PDFDocumento11 pagineMartin Mahner and Mario Bunge PDFTiago SilvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mind Over Machine - The Power of Human IDocumento6 pagineMind Over Machine - The Power of Human INueyNessuna valutazione finora

- GEC 04 Module 2 BeamerDocumento60 pagineGEC 04 Module 2 BeamerJonwille Mark CastroNessuna valutazione finora

- Searle On ConversationDocumento161 pagineSearle On ConversationtiagomluizzNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are Poets For? PDFDocumento25 pagineWhat Are Poets For? PDFVicky DesimoniNessuna valutazione finora

- Discrete Structures Set Theory: Duy BuiDocumento8 pagineDiscrete Structures Set Theory: Duy BuiAwode TolulopeNessuna valutazione finora

- FIRST Semester, AY 2020-2021 I. Course: II. Course DescriptionDocumento17 pagineFIRST Semester, AY 2020-2021 I. Course: II. Course DescriptionKimberly SoruilaNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 Critical Reading StrategiesDocumento2 pagine7 Critical Reading StrategiesNor AmiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Ib Psych Command TermsDocumento2 pagineIb Psych Command Termsloveis102050% (2)

- Accounting Is An InstrumentDocumento21 pagineAccounting Is An Instrumentclaudia_claudia1111Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Brief Guide To Writing Philosophy PapersDocumento8 pagineA Brief Guide To Writing Philosophy PapersrussmccormNessuna valutazione finora

- The Necessity of Grammar TeachingDocumento4 pagineThe Necessity of Grammar TeachingDuc Nguyen MinhNessuna valutazione finora

- Cultural Relativism': Human Rights QuarterlyDocumento47 pagineCultural Relativism': Human Rights QuarterlyLixo ElectronicoNessuna valutazione finora

- Susan Haack Femnist Epistemology PDFDocumento13 pagineSusan Haack Femnist Epistemology PDFPedroNessuna valutazione finora

- Commentary of Educating RitaDocumento2 pagineCommentary of Educating RitaJessica Linares CuervoNessuna valutazione finora

- De Morgan's Laws Revisited: To Be AND/OR NOT To Be: Raoul A. Bernal, Amgen, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CADocumento4 pagineDe Morgan's Laws Revisited: To Be AND/OR NOT To Be: Raoul A. Bernal, Amgen, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CAbennelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Filosofia Spațiului Și Timpului: Curs 7Documento24 pagineFilosofia Spațiului Și Timpului: Curs 7Adriana TodoroviciNessuna valutazione finora

- (Developments in International Law 46) Stéphane Beaulac - The Power of Language in the Making of International Law_ The Word Sovereignty in Bodin and Vattel and the Myth of Westphalia-Martinus Nijhof.pdfDocumento215 pagine(Developments in International Law 46) Stéphane Beaulac - The Power of Language in the Making of International Law_ The Word Sovereignty in Bodin and Vattel and the Myth of Westphalia-Martinus Nijhof.pdfÜmber EhitusNessuna valutazione finora

- 3.research InsightsDocumento19 pagine3.research InsightsRomana NakonechnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rombeiro - Intelligible Species Mature Thought Henry of Ghent (Enrique de Gand)Documento41 pagineRombeiro - Intelligible Species Mature Thought Henry of Ghent (Enrique de Gand)Umberto MartiniNessuna valutazione finora

- An Kit ShahDocumento10 pagineAn Kit ShahCarmelo R. CartiereNessuna valutazione finora

- Badiou - The Three NegationsDocumento7 pagineBadiou - The Three NegationsChristina Soto VdPlasNessuna valutazione finora

- Kant's Transcendental Deductions - The Three 'Critiques' and The 'Opus Postumum' (Studies in Kant and German Idealism) (PDFDrive - Com) - 1Documento293 pagineKant's Transcendental Deductions - The Three 'Critiques' and The 'Opus Postumum' (Studies in Kant and German Idealism) (PDFDrive - Com) - 1Thamires Alessandra100% (1)

- Alien Abduction Study Conference Mit Summary ReportDocumento5 pagineAlien Abduction Study Conference Mit Summary ReportGregory O'Dell100% (1)

- Legal Technique Midterm NotesDocumento7 pagineLegal Technique Midterm NotesChristia Sandee SuanNessuna valutazione finora

- De Vogel Greek Philosophy Aristotle PDFDocumento345 pagineDe Vogel Greek Philosophy Aristotle PDFsamm123456Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Rational Nature of ManDocumento17 pagineThe Rational Nature of ManLuna TremeniseNessuna valutazione finora

- (Starting With) Andrew Ward - Starting With Kant (2012, Continuum)Documento191 pagine(Starting With) Andrew Ward - Starting With Kant (2012, Continuum)Habib HaamidNessuna valutazione finora

- Humanistic-Existential Approach: What Is Humanism?Documento6 pagineHumanistic-Existential Approach: What Is Humanism?yohanesNessuna valutazione finora