Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Lehman Brothers

Caricato da

Kerry1201Descrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Lehman Brothers

Caricato da

Kerry1201Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Lehman Brothers Collapse Causes: Malfeasance A March 2010 report by the court-appointed examiner indicated that Lehman executives

regularly used cosmetic accounting gimmicks at the end of each quarter to make its finances appear less shaky than they really were. This practice was a type of repurchase agreement that temporarily removed securities from the company's balance sheet. However, unlike typical repurchase agreements, these deals were described by Lehman as the outright sale of securities and created "a materially misleading picture of the firms financial [42] condition in late 2007 and 2008." Subprime mortgage crisis In August 2007 the firm closed its subprime lender, BNC Mortgage, eliminating 1,200 positions in 23 locations, and took an after-tax charge of $25 million and a $27 million reduction in goodwill. Lehman said that poor market conditions in the mortgage space "necessitated a substantial reduction in its resources and capacity in the [43] subprime space". In 2008, Lehman faced an unprecedented loss to the continuing subprime mortgage crisis. Lehman's loss was a result of having held on to large positions in subprime and other lower-rated mortgage trancheswhen securitizing the underlying mortgages; whether Lehman did this because it was simply unable to sell the lowerrated bonds, or made a conscious decision to hold them, is unclear. In any event, huge losses accrued in lowerrated mortgage-backed securities throughout 2008. In the second fiscal quarter, Lehman reported losses of $2.8 billion and was forced to sell off $6 billion in [44] assets. In the first half of 2008 alone, Lehman stock lost 73% of its value as the credit market continued to [44] tighten. In August 2008, Lehman reported that it intended to release 6% of its work force, 1,500 people, just ahead of its third-quarter-reporting deadline in [44] September. In September 2007, Joe Gregory appointed Erin Callan as CFO. On March 16, 2008, after rival Bear Stearns was taken over by JP Morgan Chase in a fire sale, market analysts suggested that Lehman would be the next major investment bank to fall. Callan fielded Lehman's first quarter conference call, where the firm posted a profit of $489 million, compared to Citigroup's $5.1 billion and Merrill Lynch's $1.97 billion losses which was Lehmans 55th consecutive profitable quarter. The firm's stock price leapt 46 percent after that announcement. On June 9, 2008, Lehman Brothers announced US$2.8 billion second-quarter loss, its first since being spun off from American Express, as market volatility rendered many of its hedges ineffective during that time. Lehman also reported that it had raised a further $6 billion in capital. As a result, there was major management shakeup, when Hugh "Skip" McGee III (head of investment banking) held a meeting with senior staff to strip Fuld and his lieutenants of their authority. Consequently, Joe Gregory agreed to resign as President and COO, and afterward he told Erin Callan

that she had to resign as CFO. Callan was appointed CFO of Lehman in 2008 but served only for six months, before departing after her mentor Joe Gregory was [45][46][47] demoted. Bart McDade was named to succeed Gregory as President and COO, when several senior executives threatened to leave if he was not promoted. McDade took charge and brought back Michael Gelband and Alex Kirk, who had previously been pushed out of the firm by Gregory for not taking risks. Although Fuld remained CEO, he soon became isolated from [33][48] McDade's team. On August 22, 2008, shares in Lehman closed up 5% (16% for the week) on reports that the statecontrolled Korea Development Bank was considering [49] buying the bank. Most of those gains were quickly eroded as news came in that Korea Development Bank was "facing difficulties pleasing regulators and attracting [50] partners for the deal." It culminated on September 9, when Lehman's shares plunged 45% to $7.79, after it was reported that the state-run South Korean firm had [51] put talks on hold. On September 17, 2008 Swiss Re estimated its overall net exposure to Lehman Brothers as [52] approximately CHF 50 million. Investor confidence continued to erode as Lehman's stock lost roughly half its value and pushed the S&P 500 down 3.4% on September 9. The Dow Jones lost 300 points the same day on investors' concerns about [53] the security of the bank. The U.S. government did not announce any plans to assist with any possible financial [54] crisis that emerged at Lehman. The next day, Lehman announced a loss of $3.9 billion and its intent to sell off a majority stake in its investmentmanagement business, which includes Neuberger [55][56] Berman. The stock slid seven percent that [56][57] day. Lehman, after earlier rejecting questions on the sale of the company, was reportedly searching for a buyer as its stock price dropped another 40 percent on [57] September 11, 2008. Just before the collapse of Lehman Brothers, executives at Neuberger Berman sent e-mail memos suggesting, among other things, that the Lehman Brothers' top people forgo multi-million dollar bonuses to "send a strong message to both employees and investors that management is not shirking accountability for recent [58] performance." Lehman Brothers Investment Management Director George Herbert Walker IV dismissed the proposal, going so far as to actually apologize to other members of the Lehman Brothers executive committee for the idea of bonus reduction having been suggested. He wrote, "Sorry team. I am not sure what's in the water at Neuberger Berman. I'm embarrassed and I [58] apologize." Short-selling allegations During hearings on the bankruptcy filing by Lehman Brothers and bailout of AIG before the House Committee [59] on Oversight and Government Reform, former Lehman Brothers CEO Richard Fuld said a host of factors including a crisis of confidence and naked shortselling attacks followed by false rumors contributed to both the collapse of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers.

House committee Chairman Henry Waxman said the committee received thousands of pages of internal documents from Lehman and these documents portray a company in which there was no accountability for [60][61][62] failure". An article by journalist Matt Taibbi in Rolling Stone contended that naked short selling contributed to [63] the demise of both Lehman and Bear Stearns. A study by finance researchers at the University of Oklahoma Price College of Business studied trading in financial stocks, including Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, and found "no evidence that stock price declines were [64] caused by naked short selling". Bankruptcy On Saturday, September 13, 2008, Timothy F. Geithner, the then president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, called a meeting on the future of Lehman, which included the possibility of an emergency liquidation of its [65] assets. Lehman reported that it had been in talks with Bank of America and Barclays for the company's possible sale. However, both Barclays and Bank of America ultimately declined to purchase the entire [65][66] company. The next day, Sunday, September 14, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) offered an exceptional trading session to allow market participants to offset positions in various derivatives on the condition [67] of a Lehman bankruptcy later that day. Although the bankruptcy filing missed the deadline, many dealers [68] honored the trades they made in the special session. Shortly before 1 am Monday morning (New York time), Lehman Brothers Holdings announced it [69] would file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection citing bank debt of $613 billion, $155 billion in bond debt, and [70] assets worth $639 billion. It further announced that its [69] subsidiaries would continue to operate as normal. A group of Wall Street firms agreed to provide capital and financial assistance for the bank's orderly liquidation and the Federal Reserve, in turn, agreed to a swap of lowerquality assets in exchange for loans and other [71] assistance from the government. The morning witnessed scenes of Lehman employees removing files, items with the company logo, and other belongings from the world headquarters at 745 Seventh Avenue. The spectacle continued throughout the day and into the following day. Later that day, the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) suspended Lehman's Australian subsidiary as a market participant after clearing-houses terminated contracts [72] with the firm. Lehman shares tumbled over 90% on [73][74] September 15, 2008. The Dow Jones closed down just over 500 points on September 15, 2008, which was at the time the largest drop in a single day since the [75] days following the attacks on September 11, 2001. In the United Kingdom, the investment bank went into administration with PricewaterhouseCoopers appoin [76] ted as administrators. In Japan, the Japanese branch, Lehman Brothers Japan Inc., and its holding company filed for civil reorganization on September 16, 2008, [77] in Tokyo District Court. On September 17, 2008, the [78] New York Stock Exchange delisted Lehman Brothers.

On March 16, 2011 some three years after filing for bankruptcy and following a filing in a Manhattan U.S. bankruptcy court, Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc announced it would seek creditor approval of its reorganization plan by October 14 followed by a [79] confirmation hearing to follow on November 17. Liquidation Barclays acquisition On Tuesday, September 16, 2008, Barclays plc announced that they would acquire a "stripped clean" portion of Lehman for $1.75 billion, including most of [3][80] Lehman's North America operations. On September 20, this transaction was approved by U.S. Bankruptcy [81][82] Judge James Peck. On September 20, 2008, a revised version of the deal, a $1.35 billion (700 million) plan for Barclays to acquire the core business of Lehman (mainly its $960-million [83] headquarters, a 38-story office building in Midtown Manhattan, with responsibility for 9,000 former employees), was approved. Manhattan court bankruptcy Judge James Peck, after a 7-hour hearing, ruled: "I have to approve this transaction because it is the only available transaction. Lehman Brothers became a victim, in effect the only true icon to fall in a tsunami that has befallen the credit markets. This is the most momentous bankruptcy hearing I've ever sat through. It can never be deemed precedent for future cases. It's hard for me to [84] imagine a similar emergency." Luc Despins, then a partner at Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy, the creditors committee counsel, said: "The reason we're not objecting is really based on the lack of a viable alternative. We did not support the transaction because there had not been enough time to properly [citation needed] review it." In the amended agreement, Barclays would absorb $47.4 billion in securities and assume $45.5 billion in trading liabilities. Lehman's attorney Harvey R. Miller of Weil, Gotshal & Manges, said "the purchase price for the real estate components of the deal would be $1.29 billion, including $960 million for Lehman's New York headquarters and $330 million for two New Jersey data centers. Lehman's original estimate valued its headquarters at $1.02 billion but an appraisal from CB Richard Ellis this week valued it at [citation needed] $900 million." Further, Barclays will not acquire Lehman's Eagle Energy unit, but will have entities known as Lehman Brothers Canada Inc, Lehman Brothers Sudamerica, Lehman Brothers Uruguay and its Private Investment Management business for high networth individuals. Finally, Lehman will retain $20 billion of securities assets in Lehman Brothers Inc that are not [85] being transferred to Barclays. Barclays acquired a potential liability of $2.5 billion to be paid as severance, if it chooses not to retain some Lehman employees [86][87] beyond the guaranteed 90 days. Nomura acquisition Nomura Holdings, Japan's top brokerage firm, agreed to buy the Asian division of Lehman Brothers for $225 million and parts of the European division for a [88][89] nominal fee of $2. It would not take on any trading assets or liabilities in the European units. Nomura negotiated such a low price because it acquired only Lehman's employees in the regions, and not its stocks,

bonds or other assets. The last Lehman Brothers Annual Report identified that these non-US subsidiaries of Lehman Brothers were responsible for over 50% of [90] global revenue produced. Sale of asset management businesses On September 29, 2008, Lehman agreed to sell Neuberger Berman, part of its investment management business, to a pair of private-equity firms, Bain Capital Partners and Hellman & Friedman, for [91] $2.15 billion. The transaction was expected to close in early 2009, subject to approval by the U.S. Bankruptcy [92] Court, but a competing bid was entered by the firm's management, who ultimately prevailed in a bankruptcy auction on December 3, 2008. Creditors of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. retain a 49% common equity interest in the firm, now known as Neuberger Berman [93] Group LLC. In Europe, the Quantitative Asset Management Business has been acquired back by its employees on November 13, 2008 and has been renamed back to TOBAM. Financial fallout Lehman's bankruptcy was the largest failure of an investment bank since Drexel Burnham Lambert collapsed amid fraud allegations 18 years [71] prior. Immediately following the bankruptcy filing, an already distressed financial market began a period of extreme volatility, during which the Dow experienced its largest one day point loss, largest intra-day range (more than 1,000 points) and largest daily point gain. What followed was what many have called the perfect storm of economic distress factors and eventually a $700bn bailout package (Troubled Asset Relief Program) prepared by Henry Paulson, Secretary of the Treasury, and approved by Congress. The Dow eventually closed at a new six-year low of 7,552.29 on November 20, followed by a further drop to 6626 by March of the next year. Durvexity spiked, due to funding issues at the [94] major investment banks. The fall of Lehman also had a strong effect on small private investors such as bond holders and holders of so-called Minibonds. In Germany structured products, often based on an index, were sold mostly to private investors, elderly, retired persons, students and families. Most of those now worthless derivatives were sold by the German arm of Citigroup, the German Citibank now owned by Crdit Mutuel. Ongoing litigation On March 11, 2010, Anton R. Valukas, a court-appointed examiner, published the results of its year-long investigation into the finances of Lehman [95] Brothers. This report revealed that Lehman Brothers used an accounting procedure termed repo 105 to temporarily exchange $50 billion of assets into cash just [96] before publishing its financial statements. The action could be seen to implicate both Ernst & Young, the bank's accountancy firm and Richard S. Fuld, Jr, the [97] former CEO. This could potentially lead to Ernst & Young being found guilty of financial malpractice and [98] Fuld facing time in prison. According to the Wall Street Journal, in March 2011, the SEC announced that they weren't confident that they

could prove that Lehman Brothers violated US laws in its [99] accounting practices. In October 2011 the administrators of Lehman Brothers Holding Inc. lost their appeal to overturn a court order forcing them to pay 148 million into their underfunded [100] pensions plan. The Bear Stearns Conspiracy This is one scandal the National Enquirer has not reported. No babies with mystery fathers, no former vice presidential candidates cowering in a hotel basement to escape the paparazzi. This scandal, relegated to the business pages if covered at all, is un-juicy compared to l'affaire Edwards, with a wife betrayed, children humiliated, hypocrisy exposed--it is a small wonder, after the ethical hemming and hawing, that the big-time publishers and broadcasters jumped in to take part in the fun. Yet, entertainment value aside, the Edwards scandal directly affected almost nobody but the Edwards family and a few disillusioned followers. The Bear Stearns scandal continues to affect tens of thousands of people in all sorts of ways. As the story lacked prurient interest, it was left to Bloomberg.com to unearth persuasive information that the Wall Street firm was seemingly brought down by a conspiracy that netted its participants a profit of upwards of $250 million on an investment of $1.7 million in a week or so. Nice work, if you can get it. The putative conspirators, whose name or names have not been made public, pulled off their heist with ease. They bought a bunch of what Wall Street calls "puts." A put is a piece of paper guaranteeing its owner the right to sell 100 shares of stock at a stated price within a specified period of time. In the case of this bank job, the period of time was as little as five days. With Bear Stearns stock selling at over $60 a share, somebody bought the right to sell almost 6 million shares at $30 a share. To make money on these puts, the price of Bear Stearns stock would have to lose more than half its value fast. In fact, in the days immediately after the unknown person or persons bought all those puts, Bears Stearns stock dropped like a duck shot out of the sky, to a price of $10 a share or less. The persons behind the scheme then bought Bear Stearns shares at $10 or less and exercised the puts, thereby selling them for $30 and pocketing the difference. How could someone know that in a matter of days the fifth-largest trading house on Wall Street would see the value of its stock drop to next to nothing? "Even if I were the most bearish man on earth, I can't imagine buying puts 50 percent below the price with just over a week to expiration," says Thomas Haugh, general partner of Chicago-based options trading firm PTI Securities & Futures LP, cited by Gary Matsumoto of Bloomberg. "It's not even on the page of rational behavior, unless you know something." Then with the price of stock still above $50, somebody bought puts giving them the right to sell the stock at five dollars a share--which is about what you would expect to be the price of the shares of a company in bankruptcy. Matsumoto quotes one broker as saying, "When you buy $5 strikes [puts] when the stock is trading over $50, you

either have to be manipulating, or you have to have insider information." Another broker quoted in his report remarked, "Nobody in their right mind would buy that put unless you knew what was going down." The timing of the purchase of the puts screams out that a well-placed person inside Bear Stearns was telling someone on the outside of the firm's increasing confusion and division. At a crucial moment when rumors were rife on Wall Street that Bear Stearns customers would not be able to withdraw their money, the stock market was hit by a large number of orders to sell Bear Stearns stock. That augmented the force of the rumors of insolvency already working to depress the price, even as panicky customers fell over one another getting their money out. There are too many disastrous coincidences here to be explained just by bad luck. The name of the bearer of this bad luck remains hidden. A spokeswoman for the Chicago Board of Options Exchange, where the puts were bought, has refused to tell Bloomberg the name. We know the name of the mother of the baby John Edwards did or did not sire, but we are in the dark as to who may have authored the scheme that cost thousands of people their jobs and their savings and that gave the financial markets a major kick down the mountain, a fall that will continue to take millions of us with them. The Regulatory Failure behind the Bear Stearns Debacle Bear Stearns never ran short of capital. It just could not meet its obligations. At least that is the view from Washington, where regulators never stepped in to force the investment bank to reduce its high leverage even after it became clear Bear was struggling last summer. Instead, the regulators issued repeated reassurances that all was well. Bears principal regulator was the Securities and Exchange Commission, which says it was watching closely. At all times, wrote Christopher Cox, the S.E.C. chairman, in the aftermath of the collapse, the firm had a capital cushion well above what is required to meet supervisory standards. Even when the Federal Reserve concluded it had to subsidize a takeover of Bear by JPMorgan Chase to preserve the financial system, Mr. Cox wrote, Bear qualified under the Feds rules as well capitalized. Could that indicate there is something wrong with the Feds rules? Does it sound a little like a doctor emerging from a funeral to proclaim that he did an excellent job of treating the late patient? The S.E.C. does not see it that way. It its view, this was a case of an old-fashioned bank run, and no capital standards can stop such a run when confidence is lost. That kind of statement is a condemnation of the kind of supervision that the S.E.C. did, said one expert on financial regulation, Edward J. Kane, a finance professor at Boston College, in an interview this week. If there is good capital, you should be able to convince your counterparties of it. The S.E.C. assumed that Bear, or any other investment bank, could always borrow against securities it owned. It assumed that lenders would put up at least 93 percent of the value of those securities, and as much as 97 percent for the safer ones.

In a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Analysis, prepared for a conference to be held next week at Cambridge University, Mr. Kane assigned some of the blame for the current credit crisis to international regulatory competition, in which national regulators, fearful of seeing business go overseas, dared not be too tough. Instead, regulators from around the world agreed on common capital standards, the latest version of which is known as Basel II. That standard has loopholes that allowed banks to add lots of leverage, some of it pushed off balance sheets in ways that obscured the risks that remained and minimized the apparent need for capital. The job of determining the risk of various assets, and thus the amount of capital needed, was largely subcontracted to bond rating agencies and to the banks themselves. On the grounds that the y were helping innovative U.S. firms to compete effectively in global markets, federal supervisors refused to take on the political and practical challenge of establishing and maintaining their ability to see and to discipline complicated risk exposures, Mr. Kane said. If any big bank was going to have a lot of leverage, it was almost inevitable that all would. In good times, it is hard for a more conservative institution to stay competitive when its rivals use borrowing to magnify profits. It is no coincidence that the crisis of 2007 and 2008 had its origin in unregulated financial products traded in unregulated markets. Ever since the Great Depression, the government has tried to limit the leverage available to the public in the American stock market. But regulators, led by Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the Federal Reserve, thought innovation would be hampered, and financial activity driven overseas, if there were any attempts to impose limits on leverage in the unregulated markets. The Treasury Department regulatory overhaul proposal introduced this week had its genesis in a move to relax regulation to make American markets more competitive. The proposal took for granted the benefits of financial innovation, but unfortunately was released just when that innovation was shown to have failed in ways that left the American credit system largely dependent on government guarantees to function at all. Few mortgage loans are now being made without some kind of guarantee from the government or from governmentsponsored enterprises, and investment banks now have the assurance they can borrow from the Federal Reserve. A severely overleveraged banking system may be portrayed as an accident waiting to happen, Mr. Kane wrote. A regulation-induced crisis occurs when misfortune impacts a banking system whose managers have made their institutions vulnerable to this amount and type of bad luck. For now, market revulsion is limiting leverage in the system and driving banks to raise more capital if they can. Mr. Cox told a Senate hearing Thursday that the Basel committee should think more about liquidity. But there has been no admission from regulators that they

erred in letting leverage get so far out of hand that a well capitalized company could not find anyone willing to lend it money without government help. The Story Behind Parmalat's Bankruptcy by Claudio Celani The bankruptcy of the giant food company Parmalat, warned Italian Finance Minister Giulio Tremonti on Dec. 22, runs the risk of leading to "general corporate insolvency" in Italy, if there is a run on corporate bonds. Throughout Europe, financial operators are nervous about the enormous sums of fraudulent financial paper that went up in smokeand about where the trail of criminal investigation will lead. A senior European financial source, for example, told EIR that Parmalat's collapse throws a spotlight on the huge volume of dirty deals that are being run by top international banks through offshore centers such as the Cayman Islands. These deals are often used to finance political, illegal, or high-risk speculative efforts, he said, and the Parmalat scandal could expose this entire dirty sub-structure of the global financial system, with unforeseeable financial as well as political consequences. Parmalat is the largest Italian food company and the fourth largest in Europe, controlling 50% of the Italian market in milk and milk-derivative products. Suddenly, it was discovered that its claimed liquidity of 4 billion euro did not exist, and that EU 8 million in bonds of investors' money had evaporated as well. Parmalat is the largest bankruptcy in European history, representing 1.5% of Italian GNPproportionally larger than the combined ratio of the Enron and WorldCom bankruptcies to the U.S. GNP. Behind Parmalat's facade as a productive agro-industrial company with 34,000 employees, hides a giant financial speculative scheme to lure investors' money and syphon it off through a network of 260 international offshore speculative entities, where the money disappeared. It has been reported that at the receiver-end of that scheme, the Cayman Islands-based offshore entity called Bonlat had invested $6.9 billion in interest swaps, the highest-risk derivatives operations. So far, through this scheme, at least EU 8 billion have disappeared, but the figure is provisory. It is now being discovered that over the years, Parmalat had become a tool of the banks, which had invented, built up, and managed the speculative scheme. Which banks? The list currently investigated by prosecutors in Parma and Milan reads like the Burke's Peerage of the international financial system: Bank of America, Citicorp, J.P. Morgan, Deutsche Bank, Banco Santander, ABN; it goes on with all the largest Italian banks: Capitalia (Rome), S. Paolo-IMI (Turin), Intesa-BCI (Milan), Unicredito (Genoa-Milan), Monte dei Paschi (Siena), to name just a few. How It Developed The story began in 1997, when Parmalat decided to become a "global player" and started a campaign of international acquisitions, especially in North and South America, financed through debt. Soon, Parmalat became the third largest cookie-maker in the United States. But such acquisitions, instead of bringing in profits, started,

no later than 2001, to bring in red figures. Losing money on its productive activities, the company shifted more and more to the high-flying world of derivatives and other speculative enterprises. Parmalat's founder and now former CEO Calisto Tanzi engaged the firm in several exotic enterprises, such as a tourism agency called Parmatour, and the purchase of the local soccer club Parma. Huge sums were poured into these two enterprises, which have been a loss from the very beginning. It has been reported that Parmatour, now closed, has a loss of at least EU 2 billion, an incredibly high figure for a tourist agency. The losses of the Parma soccer club are not yet fully known. Here, Parma insiders are pointing at what they call the "Medelln Cartel" connectioni.e., the purchase of overpriced Colombian soccer players, and other extravagances. While accumulating losses, and with debts to the banks, Parmalat started to built a network of offshore mail-box companies, which were used to conceal losses, through a mirror-game which made them appear as assets or liquidity, while the company started to issue bonds in order to collect money. The security for such bonds was provided by the alleged liquidity represented by the offshore schemes. The largest bond placers have been Bank of America, Citicorp, and J.P. Morgan. These banks, like their European and Italian partners, rated Parmalat bonds as sound financial paper, when they knew, or should have known, that they were worth nothing. While Bank of America has participated as a partner in some of Parmalat's acquisitions, Citicorp is alleged to have built up the fraudulent accounting system. What strikes one is not only the dimension of the scheme, but the arrogance of its authors. For instance, one of the offshore mail-box firms used to channel the liquidity coming from the bond sales was called Buconero, which means "black hole"! Appropriately, the first class-action suit in the United States on the Parmalat case, filed by the South Alaskan Miners' Pension Fund, is against Parmalat, its auditors, Bank of America, and Citicorpand focusses on Buconero. "The Parmalat fraud has been mainly implemented in New York, with the active role of the Zini legal firm and of Citibank," said San Diego lawyer Darren Robbins, a partner in the firm Milberg Weiss Bershad Hynes & Lerach, which is leading the class-action suit. "We believe that Citigroup, by creating instruments like the sadly famous 'Buconero,' has played a fundamental role in helping Parmalat to fake their balance sheets and hide their real financial situation." The New York-based Zini lawfirm named by Robbins, has played a role which seems to have come out of the movie The Godfather. Through Zini, firms owned by Parmalat have been sold to certain American citizens with Italian surnames, only to be purchased again by Parmalat later. The whole operation was fake: The money for the sale in the first place came from other entities owned by Parmalat, and it served only to create "liquidity" in the books. Thanks to that liquidity, Parmalat could keep issuing bonds. Mafia? Former CEO Tanzi declared to prosecutors in Parma that the fraudulent bonds system "was fully the banks' idea." Parmalat's

former financial manager, Fausto Tonna, counterfeited Parmalat's balance sheets in order to provide security for the bonds, but "it was the banks which proposed it to Tonna," Tanzi declared. Tanzi's version has been so far confirmed by Luciano Spilingardi, head of Cassa di Risparmio di Parma and member of the Parmalat board. Bond issues were ordered by the banks, Spilingardi said to prosecutors, according to leaks published in the daily La Repubblica. "I remember," Spilingardi says, "that one of the last issues, of 150 million euros, was presented to the board meeting as an explicit request by a foreign bank, which was ready to subscribe the entire bond. If I remember correctly, it was Deutsche Bank." Spilingardi says that he expressed "perplexity" about the proposal, because a previous bond issue of EU 600 million had failed, in the Spring of 2003, causing a 10% fall of Parmalat stocks in one day. But the request was accepted, and the last Parmalat bond, issued in Summer 2003, made its way to the Cayman Islands black hole. At the moment of Parmalat's default, in December 2003, the financial manager of Parmalat was no longer Tonna, who had left after the failed bond issue in the Spring. He has been replaced by Alberto Ferraris, who comes from ... Citibank. In June 2003, before the last bond issue "ordered" by Deutsche Bank, Parmalat's board gained a new member: Luca Sala, a top manager coming from ... Bank of America. The Parmalat crisis finally broke out on Dec. 8, when the company Parmalat defaulted on a EU 150 million bond. The management claims that this was because a customer, a speculative fund named Epicurum, did not pay its bills. Allegedly, Parmalat has won a derivatives contract with Epicurum, betting against the dollar. But it was soon discovered that Epicurum is owned by firms whose address is the same as some of Parmalat's own offshore entities. In other words, Epicurum is owned by Parmalat. On Dec. 9, as rumors spread that Parmalat's claimed liquidity was not there, Standard & Poor's finally downgraded Parmalat bonds to junk status, and in the next few days, Parmalat stocks fell 40%. On Dec. 12, the Parmalat management somehow found the money to pay the bond, but on Dec. 19 came the end: Bank of America announced that an account with allegedly $3.9 billion in liquidity, claimed by Parmalat at BoA, did not exist. In one shot, the bankruptcy was revealed, and Parmalat stocks fell an additional 66%. Later, Tonna would confess that he had faked BoA documents, using a scanner, scissors, and glue, to "invent" such a $3.9 billion account, a version which is still the official one. 'Systemic Risk' On Dec. 22, the Italian government rushed through emergency legislation aimed at allowing quick bankruptcy procedures for Parmalat, in order to protect its industrial activity, payrolls, vendors, etc., from creditors' claims. The government appointed Enrico Bondi to present a reorganization plan by Jan. 20. So far, so good. But Bondi, who had already replaced Tanzi a few days before, has two loyalties: he was appointed by the government, but he is also a man trusted by the banks, including for his reorganization of the Ferruzzi-

Montedison group, which was eventually sold to the Agnelli group. Fears are that Bondi will obey the banks, which want to chop up Parmalat and sell it in pieces the plan feared by the trade unions and, at least publicly, by the government itself. That same day, Paolo Raimondi, head of the Italian LaRouche movement, issued a statement in which he said that the Parmalat bankruptcy, like the Cirio, Enron, and LTCM cases, "are not isolated cases in an otherwise functioning system. Instead, they are the most evident manifestation of the bankruptcy of the entire financial system." After pointing to the role of derivative speculation in the Parmalat case, Raimondi stressed that Citigroup and Bank of America, Parmalat's main financial partners, are "the number two and three among banks involved in derivatives operations." Because it is not just a firm at stake but the whole system, "the solution must be a global one," Raimondi said, pointing to Lyndon LaRouche's proposal for a world financial reorganization called a New Bretton Woods. "The Italian Parliament has already discussed, in the past, a series of motions on the New Bretton Woods, which were introduced on different occasions by Senators Pedrizzi and Peterlini, and by Representative Brugger, and received support from a hundred members of Parliament, from all parties." Raimondi also called the recent statement by "a high moral authority, such as Milan Cardinal Dionigi Tettamanzi, who, presented with the New Bretton Woods proposal, said that the Italian government not only can, but must, promote it." Over Christmas, this statement was circulated in Italy, and distributed in Parma by LaRouche Youth Movement organizers. The Italian government is aware of the systemic dimensions of the crisis, at least as concerns the Italian bond market, as Minister Tremonti's Dec. 22 statement about "general corporate insolvency" shows. "Do you have any idea," said Tremonti to his colleagues, "of what would happen if the market demanded liquidation of money invested in corporate bonds? Therefore, we must quickly review current legislation protecting investors." Tremonti referred to 100,000 Italian owners of Parmalat bonds, mostly families which have been advised by their banks to buy paper which is now worth nothing. This is the third large insolvency hitting Italian investors in one year: The first, the Argentinian insolvency, wiped out EU 12 billion euro in bonds owned by 450,000 Italians; then, the bankruptcy of Cirio, another food company, meant a default on EU 1.2 billion in bonds owned by 40,000 families. Panic is already spreading, and a run on the Italian bond market is on the horizon. Bank stocks have plunged, with Capitalia, the main Italian creditor of Parmalat, having lost 40% since Dec. 4. The red thread of this catastrophe is represented by the role of the banks. Italian banks, not unlike their international colleagues, have lured unaware customers into high-risk investmentsworkers, pensioners, and professionals who, in most cases, did not know where their money was invested, or who were fraudulently told that it was "safely" invested. In the Argentinian bonds case, consumer organizations have filed a legal action against the banks, because they

failed to inform customers, as prescribed by law, that the investment was a high-risk one. In the Cirio case, it came out that on the eve of the company's insolvency, creditor banks rushed to dump their Cirio bonds, by selling them to their customers! And Italian newspapers are now publishing letters by owners of Parmalat bonds, telling how they were still being sold such bonds by their banks on Dec. 11, two days after the first Parmalat default, and after Standard & Poor's had downgraded them to "junk" status! The role of the banks, and of their putative supervisor, the Bank of Italy, has been the issue of an all-out war between Tremonti and BoI Governor Antonio Fazio, since the Cirio default. Things have now escalated, as the failure of BoI supervision in the Parmalat case is dramatically evident. Beyond the power struggles which are also involved, the real issue is, who controls the Bank of Italy. The fact is that the central bank, which is supposed to exercise control over the banking system, is itself controlled by the banks, which are its shareholders! The Italian central banking system is not dissimilar to the U.S. Federal Reserve or other central banking systems. Under the Bretton Woods system of regulations, however, it was partially under government control. This changed first in 1979, when deregulation freed the central bank from the obligation to buy government debt, and finally after 1992, when the largest shareholders of the Bank of Italy were privatized. These are Banca Commerciale (now Intesa-BCI), Credito Italiano (now Unicredito), IMI (now S.Paolo-IMI), and Banca Nazionale del Lavoro. The reader will recognize the names of some among Parmalat's main creditors and bond-placers. These are the controllers of the Bank of Italy, which the BoI is supposed to control. In the past months, Tremonti has led an unsuccessful battle to change this, by attempting to introduce local government representatives onto the boards of the Banking Foundations, which control Italian banks. Through that move, Tremonti hoped also to gain a handle on banking decisions to finance, for instance, infrastructure investments. He lost that battle, due to the staunch opposition of the Bank of Italy. But now the issue is again on the table, and decisions are expected to be taken after a parliamentary committee, set up after the Parmalat case broke, has investigated the current state of relations between the banking system and the corporate world. On Jan. 8, a government initiative is expected on a new control authority, which is supposed to assume the supervisory powers which the Bank of Italy had, but never implemented. HealthSouth Corporation, based in Birmingham, Alabama, is the United States's largest owner and operator of inpatient rehabilitative hospitals. Operating in 28 states across the country and in Puerto Rico, HealthSouth serves patients through its network of inpatient rehabilitation hospitals (101), outpatient rehabilitation satellite clinics (29) and home health agencies (25). HealthSouth's hospitals provide a higher

level of rehabilitative care to patients who are recovering from conditions such as stroke and other neurological disorders, orthopedic, cardiac and pulmonary conditions, brain and spinal cord injury, and amputations. HealthSouth was involved in a corporate accounting scandal in which its Founder, Chairman, and Chief Executive Officer, Richard M. Scrushy, was accused of directing company employees to falsely report grossly exaggerated company earnings in order to meet stockholder expectations. At the company's height in 2003, it recorded nearly $4.5 billion in revenue, dominated the rehabilitation, surgery and diagnostic services market and employed more than 60,000 people at 2,000 facilities in every state of the U.S. along with its facilities in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Puerto Rico and Saudi Arabia. The company was the largest publicly listed healthcare company in the United States based on the number of locations and the third based on [citation needed] revenue. By mid to late 2006, HealthSouth, which never had to file for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Protection, completed its recovery and relisted its stock on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol HLS. The company currently operates one division: inpatient rehabilitation. The company formerly operated an outpatient rehabilitation, surgery center and diagnostics division. The company also previously owned and operated several acute care hospitals that specialized in orthopedics, but sold all of those hospitals by 2006. The former outpatient division also operated an occupational medicine division until 2001, when it was sold. HealthSouth also sold its Long-term acute care facilities in May 2011. The long-term hospitals contributed around $200 million in revenue. Company beginnings HealthSouth was incorporated in Birmingham, Alabama as a Delaware company on February 22, 1984 as Amcare, Inc. by its founder Richard M. Scrushy. The company opened its first facility in Little Rock, Arkansas and one in Birmingham later that year. In 1985 the company changed its name to HealthSouth Rehabilitation Corporation. In 1986 the company went public with its IPO on the NASDAQ Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol HSRC. At the end of the company's last investor roadshow presentation in New York City before its IPO, Scrushy received a

standing ovation from the investment bankers in attendance, an extreme rarity. In September 1988 the company moved to the New York Stock Exchange and became listed under the symbol HRC. By 1990 the company had expanded to 50 facilities across the US. HealthSouth finished out 1992 with $400 million in annual revenue. In 1993 the company made its first large acquisition when it bought 28 hospitals and 45 outpatient rehabilitation facilities fromNational Medical Enterprise for around $300 million in cash. The acquisition doubled the company's annual revenue to $1 billion and also made HealthSouth the nation's largest provider of rehabilitative care. In 1994, HealthSouth further expanded when it announced it would buy fellow Birmingham-based ReLife for $180 million in stock. Growth Throughout the mid-1990s, HealthSouth expanded rapidly through mergers and acquisitions. In 1995 the company changed its name to HealthSouth Corporationto better reflect its diversified interests in healthcare. On August 31, 1995 HealthSouth CEO Richard Scrushy announced that HealthSouth was going to build a new headquarters on US Highway 280 in Birmingham. The new corporate campus was to be built 2 on 85 acres (340,000 m ) of land that the company had bought fromSouthern Company earlier that year. The corporate campus plans included a five story headquarters building with a connecting conference center and parking deck. In January 1995 the company entered the surgery center business with its $155 million acquisition of Surgical Health Corporation. One month later the company acquired Novacare's entire rehabilitational hospital business for $215 million in cash. In 1996 the company expanded into diagnostics with its purchase of Health Images Inc. In the beginning of 1996 the company adopted the slogan "The Healthcare Company of the 21st Century". Less than a year later the company adopted the "H" logo as its corporate identity. HealthSouth made its largest acquisition yet when it purchased Horizon/CMS for $1.8 billion in 1997. A few months later after the acquisition, HealthSouth sold the long-term care assets of Horizon/CMS it did not need to Integrated Health Services for $1.15 billion in cash. HealthSouth along with many Healthcare publications called this the "deal of the century". Also in February 1997 the company finally moved into its new corporate headquarters. The headquarters building itself contained

a company store and museum. HealthSouth continued on its acquisition spree through 1999 by purchasing the majority of Columbia/HCA's surgical division. In 2001 the company announced it would, along with Oracle Corporation, build the world's first all-digital hospital on its corporate campus. The 13 story structure was meant as a replacement for its aging HealthSouth Medical Center in downtown Birmingham. Construction began soon after on the new HealthSouth Medical Center. Accounting scandal The first of HealthSouth's accounting problems surfaced in late 2002 after CEO Richard M. Scrushy sold $100 million in stock several days before the company posted a large loss. HealthSouth was accused by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) of an accounting scandal where the company's earnings were falsely inflated by $1.4 billion. In 1996, Scrushy allegedly instructed the company's senior officers and accountants to falsify company earnings reports in order to meet investor expectations and control the price of the company's stock. The fraud continued for seven years. In certain fiscal years, the company's income was overstated by as much as 4700%. The $1.4 billion represents more than 10% of the company's total assets. At one point, the company's corporate taxes-based on its fraudulent earnings--were higher than its actual earnings. In 1998, HealthSouth was accused of violation of the Securities Exchange Act by failing to disclose negative trends and misrepresenting company's financial [1] information. In March 2003, HealthSouth's CEO Richard M. [2] Scrushy was charged with the accounting fraud and the SEC announced it was investigating whether Scrushy's stock sell was related to HealthSouth posting a large loss. HealthSouth hired an outside law firm to review Scrushy's stock sale, with the firm concluding that the sale and profit loss were not related, although this did not take the company off the SEC's radar. On the evening of March 18, 2003 FBI agents executed search warrants at the company's headquarters after the company's Chief Financial Officer William Owens agreed to wear a wire in a failed attempt to get Scrushy to talk about the fraud. In June 2005, Scrushy was acquitted on all 36 of the accounting fraud counts against him, most notably one

count in violation of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. However, four years later, he was sued for fraud by HealthSouth investors and ordered to repay his company $2.8 billion. Recovery and the new HealthSouth Following the raid at the company's corporate headquarters, the board of directors held an emergency meeting to discuss what actions needed to be taken. One of the first actions was the termination of Richard Scrushy as Chairman and CEO, and Bill Owens as CFO. Robert P. May was elected as interim CEO and Joel C. Gordon as Chairman. Another issue that was immediately addressed by the board was the means by which it obtain the cash for interest payments of senior bonds and principal payments due on a $344 million convertible bond. The board agreed that the company's cash flow problems were too great to tackle on its own. At the advice of its lender JPMorgan Chase, the company hired restructuring firm Alvarez and Marsal to bring its finances in order and immediately appointed Bryan Marsal Chief Restructuring Officer. By the end of 2003, the company had most of its finances reorganized and was able to avoid Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Efforts were made at the corporate headquarters to eradicate all signs of the prior existence of Scrushy within the company. The board removed Scrushy's name from the conference center, closed the company store and museum and opened the fifth floor executive offices to all employees, which, during Scrushy's tenure, had been kept away. The board also sold all but a few of the company's eleven corporate jets, which included a Gulfstream V and a Sikorsky S-76 C+ helicopter. In an effort to save money, the company halted construction of its Digital Hospital, for which building costs had doubled, to $400 million. On May 10, 2004, Jay Grinney was chosen by the board as the company's permanent CEO. Soon after Grinney's appointment, the company moved forward with its goal of again becoming a current filer with the SEC. By doing so, the company restated earnings from 2000 to 2003. The company also sold or closed many underperforming facilities, including its medical center division, in its effort to return to profitabiity. On May 15, 2006, the company completed its goal of once again becoming a current filer with the SEC when it filed its first quarter 2006 financial result. It was the first time the company had filed a 10-Q since its accounting scandal began. On August 14, 2006 the company

unveiled its restructuring plan which included the sell, spin-off or other disposition of its surgery, outpatient, and diagnostic divisions, along with a 1-for-5 reverse stock split, to coincide with its relisting on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol HLS. The reverse stock split was approved by stock holders at a special meeting at the company's corporate headquarters on October 18, 2006. The last step in HealthSouth's recovery from its accounting scandal occurred on October 26, 2006 when it was again relisted on the New York Stock Exchange. On January 29, 2007 the company announced it would sell its more than 600 outpatient centers to Select Medical Corporation for $245 million in cash. The transaction was completed on May 1, 2007. On March 26, 2007, HealthSouth announced it would sell its surgery center division to private investment partnership TPG Capital for $920 million in cash and equity interest in the newly formed company worth between $25 to $30 million. The surgery center division comprised 139 outpatient surgery centers and three surgical hospitals. It was also announced that the new surgery center company would remain headquartered in [3] Birmingham. The transaction was completed on June 30, 2007 with the creation of Surgical Care Affiliates. On April 29, 2007, HealthSouth announced a definitive agreement to sell its diagnostic division to the Gores Group for $47.5 million. It was also announced that the newly formed company was to remain in Birmingham. The transaction was completed on July 31, 2007 with Diagnostic Health Corporation being formed. In July 2010, HealthSouth gave the American Cancer Society of Alabama the black V-12 2000 BMW 750iL, a bullet-proof sedan that HealthSouth purchased for security reasons under former CEO Richard Scrushy. Scrushy bought the car from HealthSouth in 2003 after an accounting scandal broke. Scrushy also owned a maroon 2000 bullet-proof V-12 BMW 750iL that was sold in 2009 by HealthSouth as part of a civil judgment against Scrushy. In 2009, HealthSouth had obtained ownership of Scrushy's black 2000 BMW 750iL.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Lehman Brothers Holdings IncDocumento17 pagineLehman Brothers Holdings Incrachit1993Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman BrothersDocumento5 pagineLehman BrothersArslan_Gul_667Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bankruptcy of Lehman BrothersDocumento9 pagineBankruptcy of Lehman BrothershornzzNessuna valutazione finora

- Bankruptcy of Lehman BrothersDocumento12 pagineBankruptcy of Lehman Brothersavinash2coolNessuna valutazione finora

- Bankruptcy of Lehman BrothersDocumento6 pagineBankruptcy of Lehman BrothersNickNessuna valutazione finora

- Background: Bankruptcy of Lehman BrothersDocumento14 pagineBackground: Bankruptcy of Lehman Brothersrose30cherryNessuna valutazione finora

- Bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers Is TheDocumento11 pagineBankruptcy of Lehman Brothers Is Themanas_samantaray28Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bankruptcy of Lehman BrothersDocumento12 pagineBankruptcy of Lehman BrothersMihir MehtaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Brothers Case SummaryDocumento4 pagineLehman Brothers Case SummaryJevanNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study: The Collapse of Lehman Brothers: Bankruptcy Worldcom Enron Subprime MortgageDocumento4 pagineCase Study: The Collapse of Lehman Brothers: Bankruptcy Worldcom Enron Subprime Mortgageshinaru04Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Brothers Crash HistoryDocumento4 pagineLehman Brothers Crash HistoryAmit MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Leh BrosDocumento3 pagineLeh BrosHitesh BachaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study The Collapse of Lehman BrotheDocumento4 pagineCase Study The Collapse of Lehman BrotheAnurag SarrafNessuna valutazione finora

- Bankruptcy Worldcom Enron Subprime Mortgage: Who Is To Blame For The Subprime CrisisDocumento3 pagineBankruptcy Worldcom Enron Subprime Mortgage: Who Is To Blame For The Subprime Crisisrose30cherryNessuna valutazione finora

- Rise and Fall of Lehman BrothersDocumento4 pagineRise and Fall of Lehman BrothersMuneer Hussain100% (1)

- The History of Lehman BrothersDocumento6 pagineThe History of Lehman BrothersL A AnchetaSalvia DappananNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Brother FallDocumento3 pagineLehman Brother FallswetaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study Lehman BrothersDocumento9 pagineCase Study Lehman BrothersAris Surya PutraNessuna valutazione finora

- The Collapse of Lehman BrothersDocumento16 pagineThe Collapse of Lehman BrothersAkash BafnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study of Lehman Brothers CollapseDocumento4 pagineCase Study of Lehman Brothers Collapsemukesh chhotala100% (1)

- NDocumento6 pagineNAnonymous ZsGfRcvH2SNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Brothers BankruptcyDocumento3 pagineLehman Brothers BankruptcyAya KabNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman BankruptcyDocumento34 pagineLehman BankruptcyBHAVNA FATEHCHANDANI100% (13)

- Leman BrothersDocumento7 pagineLeman Brothersblueeagle477952Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman BrothersDocumento4 pagineLehman BrothersgopalushaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shaheed Sukhdev College of Business Studies New DelhiDocumento28 pagineShaheed Sukhdev College of Business Studies New Delhinavs_anandNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Brothers - Never Too Big To FailDocumento10 pagineLehman Brothers - Never Too Big To FailPredit SubbaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Brothers DownfallDocumento17 pagineLehman Brothers DownfallAli ImranNessuna valutazione finora

- Ljfa - Tp3-W3-Audit Method & Practice-Irfan Jaya Kusumah-2101751990Documento6 pagineLjfa - Tp3-W3-Audit Method & Practice-Irfan Jaya Kusumah-2101751990Irfan JayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Written Statement of Richard S. Fuld, Jr. Before The Financial Crisis Inquiry CommissionDocumento8 pagineWritten Statement of Richard S. Fuld, Jr. Before The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commissionccomstock3459Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Dearth of Ethics and The Death of Lehman Brothers: Tugas Personal Ke 3 Minggu Ke 3Documento4 pagineThe Dearth of Ethics and The Death of Lehman Brothers: Tugas Personal Ke 3 Minggu Ke 3karlinaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Story of Lehman Brothers: Nidhi Dalmia Mba Semester - I Section - A 1001563908 NiecDocumento27 pagineThe Story of Lehman Brothers: Nidhi Dalmia Mba Semester - I Section - A 1001563908 NiecAnthony RakotobeNessuna valutazione finora

- E) How They Got CaughtDocumento4 pagineE) How They Got Caughtanaury17Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1911 - F1242 - Ljfa - TP3-W3-R2 - 2101762104 - Wenni Marine JoamDocumento8 pagine1911 - F1242 - Ljfa - TP3-W3-R2 - 2101762104 - Wenni Marine JoamWenni MarineNessuna valutazione finora

- Becg Assingment On "Lehman Bankruptcy"Documento12 pagineBecg Assingment On "Lehman Bankruptcy"Sachin BabbiNessuna valutazione finora

- A Case Study On The Lehman BrothersDocumento22 pagineA Case Study On The Lehman BrothersAnne Reyes100% (1)

- Lehman ResearchDocumento7 pagineLehman ResearchFreya DaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Brothers: Ankit Purohit B.E. (ET&T) 4 Semester Section - A Bhilai Institute of TechnologyDocumento31 pagineLehman Brothers: Ankit Purohit B.E. (ET&T) 4 Semester Section - A Bhilai Institute of TechnologyAnkit PurohitNessuna valutazione finora

- Policy Fin CrisisDocumento7 paginePolicy Fin CrisisThought LeadersNessuna valutazione finora

- The Fall of Lehman BrothersDocumento5 pagineThe Fall of Lehman BrothersDr. Sanjeev KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Last Days of Lehman BrothersDocumento19 pagineThe Last Days of Lehman BrothersSalman Mohammed ShirasNessuna valutazione finora

- What If Lehman SurvivedDocumento6 pagineWhat If Lehman SurvivedTroy UhlmanNessuna valutazione finora

- From The TimesDocumento12 pagineFrom The TimespeteradrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Finanace Assignment 1Documento13 pagineFinanace Assignment 1waelNessuna valutazione finora

- Failure of Lehman Brothers: Jitendra SoniDocumento4 pagineFailure of Lehman Brothers: Jitendra Sonijitu222soni3386Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study-Lehman BrothersDocumento14 pagineCase Study-Lehman BrothersRaviNessuna valutazione finora

- AUDITDocumento2 pagineAUDITathirah jamaludinNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Brothers Holdings IncDocumento1 paginaLehman Brothers Holdings IncSamina AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment No. 3 International Finance: Lehman BrothersDocumento5 pagineAssignment No. 3 International Finance: Lehman BrothersWasim Bin ArshadNessuna valutazione finora

- Syndicate Assignment: Case Study: Letting Go of Lehman BrothersDocumento6 pagineSyndicate Assignment: Case Study: Letting Go of Lehman BrothersJane Tito100% (1)

- Lehman Brothers Holdings IncDocumento27 pagineLehman Brothers Holdings IncTushar SinglaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Bro Corporate Governance FailureDocumento18 pagineLehman Bro Corporate Governance FailureAzhar AkhtarNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Brothers (Analysis) - FinalDocumento33 pagineLehman Brothers (Analysis) - FinalAhmed RefaatNessuna valutazione finora

- MF GlobalDocumento3 pagineMF GlobalKinghim TongNessuna valutazione finora

- Remadial Assignment FinalDocumento6 pagineRemadial Assignment FinalWael Al AridiNessuna valutazione finora

- Case 3 Lehman BrothersDocumento19 pagineCase 3 Lehman BrothersYusuf UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lehman Brothers BankruptcyDocumento8 pagineLehman Brothers BankruptcyOmar EshanNessuna valutazione finora

- FinTech Rising: Navigating the maze of US & EU regulationsDa EverandFinTech Rising: Navigating the maze of US & EU regulationsValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Summary of David Carey & John E. Morris' King of CapitalDa EverandSummary of David Carey & John E. Morris' King of CapitalNessuna valutazione finora

- Leveraged Financial Markets: A Comprehensive Guide to Loans, Bonds, and Other High-Yield InstrumentsDa EverandLeveraged Financial Markets: A Comprehensive Guide to Loans, Bonds, and Other High-Yield InstrumentsNessuna valutazione finora

- Pls - Vote Chadray Guisa-Ed As A School PresidentDocumento11 paginePls - Vote Chadray Guisa-Ed As A School PresidentKerry1201Nessuna valutazione finora

- WorldCom ScandalDocumento2 pagineWorldCom ScandalKerry1201Nessuna valutazione finora

- 6.1 Exponential Function and InverseDocumento2 pagine6.1 Exponential Function and InverseKerry1201Nessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Accounting FraudCase Study of Satyam Computers LimitedDocumento13 pagineCorporate Accounting FraudCase Study of Satyam Computers LimitedchrstNessuna valutazione finora

- Record Layout DiagramsDocumento10 pagineRecord Layout DiagramsKerry1201Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nature On Trial: The Case of The Rooster That Laid An EggDocumento22 pagineNature On Trial: The Case of The Rooster That Laid An EggacaryaweareNessuna valutazione finora

- Midterm Org. ManagementDocumento5 pagineMidterm Org. Managementnm zuhdiNessuna valutazione finora

- Rosalina Buan, Rodolfo Tolentino, Tomas Mercado, Cecilia Morales, Liza Ocampo, Quiapo Church Vendors, For Themselves and All Others Similarly Situated as Themselves, Petitioners, Vs. Officer-In-charge Gemiliano c. Lopez, JrDocumento5 pagineRosalina Buan, Rodolfo Tolentino, Tomas Mercado, Cecilia Morales, Liza Ocampo, Quiapo Church Vendors, For Themselves and All Others Similarly Situated as Themselves, Petitioners, Vs. Officer-In-charge Gemiliano c. Lopez, JrEliza Den DevilleresNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. Lamahang CASE DIGESTDocumento2 paginePeople v. Lamahang CASE DIGESTRalson Mangulabnan Hernandez100% (1)

- Tax Invoice UP1222304 AA46663Documento1 paginaTax Invoice UP1222304 AA46663Siddhartha SrivastavaNessuna valutazione finora

- Form No. 1: The Partnership Act, 1932Documento3 pagineForm No. 1: The Partnership Act, 1932MUHAMMAD -Nessuna valutazione finora

- Conflict of Laws Bar ExamDocumento9 pagineConflict of Laws Bar ExamAndrew Edward BatemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Disabled Workers in Workplace DiversityDocumento39 pagineDisabled Workers in Workplace DiversityAveveve DeteraNessuna valutazione finora

- HarmanDocumento10 pagineHarmanharman04Nessuna valutazione finora

- FM 328 Module 1Documento49 pagineFM 328 Module 1Grace DumaogNessuna valutazione finora

- Print For ZopfanDocumento31 paginePrint For Zopfannorlina90100% (1)

- Iecq 03-2-2013Documento14 pagineIecq 03-2-2013RamzanNessuna valutazione finora

- Russo-Ottoman Politics in The Montenegrin-Iskodra Vilayeti Borderland (1878-1912)Documento4 pagineRusso-Ottoman Politics in The Montenegrin-Iskodra Vilayeti Borderland (1878-1912)DenisNessuna valutazione finora

- M-K-I-, AXXX XXX 691 (BIA March 9, 2017)Documento43 pagineM-K-I-, AXXX XXX 691 (BIA March 9, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (2)

- Sea Freight Sop Our Sales Routing OrderDocumento7 pagineSea Freight Sop Our Sales Routing OrderDeepak JhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Malala YousafzaiDocumento13 pagineMalala YousafzaiAde SihombingNessuna valutazione finora

- List of European Countries Via WIKIPEDIA: Ran K State Total Area (KM) Total Area (SQ Mi) NotesDocumento3 pagineList of European Countries Via WIKIPEDIA: Ran K State Total Area (KM) Total Area (SQ Mi) NotesAngelie FloraNessuna valutazione finora

- DMT280H редукторDocumento2 pagineDMT280H редукторkamran mamedovNessuna valutazione finora

- Flash Cards & Quiz: Berry Creative © 2019 - Primary PossibilitiesDocumento26 pagineFlash Cards & Quiz: Berry Creative © 2019 - Primary PossibilitiesDian CiptaningrumNessuna valutazione finora

- FCI Recruitment NotificationDocumento4 pagineFCI Recruitment NotificationAmit KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Form - 28Documento2 pagineForm - 28Manoj GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Motion To Disqualify MCAO - 7-31-13Documento14 pagineMotion To Disqualify MCAO - 7-31-13crimefileNessuna valutazione finora

- Iad Session 2 PQ Launch FinalDocumento78 pagineIad Session 2 PQ Launch FinalShibu KavullathilNessuna valutazione finora

- 2018 NFHS Soccer Exam Part 1Documento17 pagine2018 NFHS Soccer Exam Part 1MOEDNessuna valutazione finora

- Asuncion Bros. & Co., Inc. vs. Court Oflndustrial RelationsDocumento8 pagineAsuncion Bros. & Co., Inc. vs. Court Oflndustrial RelationsArya StarkNessuna valutazione finora

- Farolan v. CTADocumento2 pagineFarolan v. CTAKenneth Jamaica FloraNessuna valutazione finora

- GR 220835 CIR vs. Systems TechnologyDocumento2 pagineGR 220835 CIR vs. Systems TechnologyJoshua Erik Madria100% (1)

- Robhy Dupree ArmstrongDocumento2 pagineRobhy Dupree ArmstrongRobhy ArmstrongNessuna valutazione finora

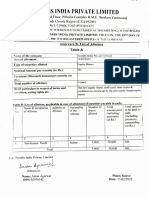

- Tectabs Private: IndiaDocumento1 paginaTectabs Private: IndiaTanya sheetalNessuna valutazione finora

- Federal Lawsuit Against Critchlow For Topix DefamationDocumento55 pagineFederal Lawsuit Against Critchlow For Topix DefamationJC PenknifeNessuna valutazione finora