Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Clinical Guideline: Screening For Chronic Kidney Disease: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

Caricato da

Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Clinical Guideline: Screening For Chronic Kidney Disease: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

Caricato da

Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Annals of Internal Medicine

Clinical Guideline

Screening for Chronic Kidney Disease: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

Virginia A. Moyer, MD, MPH, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force*

Description: New U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation statement on screening for chronic kidney disease (CKD). Methods: The USPSTF reviewed evidence on screening for CKD, including evidence on screening, accuracy of screening, early treatment, and harms of screening and early treatment. Population: This recommendation applies to asymptomatic adults without diagnosed CKD. Testing for and monitoring CKD for the purpose of chronic disease management (including testing and

monitoring patients with diabetes or hypertension) are not covered by this recommendation. Recommendation: The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of routine screening for CKD in asymptomatic adults (I statement).

Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:567-570. www.annals.org For author affiliation, see end of text. * For a list of USPSTF members, see the Appendix (available at www.annals .org). This article was published at www.annals.org on 28 August 2012.

he U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) makes recommendations about the effectiveness of specic clinical preventive services for patients without related signs or symptoms. It bases its recommendations on the evidence of both the benets and harms of the service and an assessment of the balance. The USPSTF does not consider the costs of providing a service in this assessment. The USPSTF recognizes that clinical decisions involve more considerations than evidence alone. Clinicians should understand the evidence but individualize decision making to the specic patient or situation. Similarly, the USPSTF notes that policy and coverage decisions involve considerations in addition to the evidence of clinical benets and harms.

www.annals.org) for the USPSTF grades and classication of levels of certainty about net benet.

RATIONALE

Importance

Approximately 11% of U.S. adults have CKD, many of whom are elderly. The condition is usually asymptomatic until its advanced stages. Most cases of CKD are associated with diabetes or hypertension.

Detection

SUMMARY

OF

RECOMMENDATION

AND

EVIDENCE

Chronic kidney disease is dened as decreased kidney function or kidney damage that persists for at least 3 months. No studies have assessed the sensitivity and specicity of screening for CKD with tests for estimated GFR, microalbuminuria, or macroalbuminuria.

Benefits of Detection and Early Intervention and Treatment

The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufcient to assess the balance of benets and harms of routine screening for chronic kidney disease (CKD) in asymptomatic adults (I statement). Common tests considered for CKD screening include creatinine-derived estimates of glomerular ltration rate (GFR) and urine testing for albumin. Testing for and monitoring CKD for the purpose of chronic disease management (including testing and monitoring patients with diabetes or hypertension) are not covered by this recommendation. See the Clinical Considerations section for suggestions for practice regarding the I statement. See the Figure for a summary of the recommendation and suggestions for clinical practice and Appendix Tables 1 and 2 (available at

Evidence that routine screening for CKD improves clinical outcomes for asymptomatic adults is inadequate.

See also: Print Summary for Patients. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . I-50 Web-Only Consumer Fact Sheet CME quiz (preview on page I-30)

Annals of Internal Medicine

www.annals.org 16 October 2012 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 157 Number 8 567

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by Rizka Mulya on 02/22/2013

Clinical Guideline

Screening for CKD: USPSTF Recommendation Statement

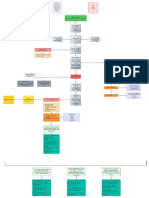

Figure. Screening for chronic kidney disease: clinical summary of U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation.

SCREENING FOR CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE CLINICAL SUMMARY OF U.S. PREVENTIVE SERVICES TASK FORCE RECOMMENDATION

Population Recommendation Asymptomatic adults without diagnosed chronic kidney disease (CKD) No recommendation. Grade: I (Insufficient Evidence)

Risk Assessment

There is no generally accepted risk assessment tool for CKD or risk for complications of CKD. Diabetes and hypertension are well-established risk factors with strong links to CKD. Other risk factors for CKD include older age, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and family history. Although there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening, the tests often suggested for screening that are feasible in primary care include testing the urine for protein (microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria) and testing the blood for serum creatinine to estimate glomerular filtration rate. The USPSTF could not determine the balance between the benefits and harms of screening for CKD in asymptomatic adults. The USPSTF has made recommendations on screening for diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, as well as aspirin use for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. These recommendations are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

Screening Tests

Balance of Harms and Benefits Other Relevant USPSTF Recommendations

For a summary of the evidence systematically reviewed in making this recommendation, the full recommendation statement, and supporting documents, please go to www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

Harms of Detection and Early Intervention and Treatment

Evidence on the harms of screening for CKD is inadequate. However, convincing evidence shows that medications used to treat early CKD may have adverse effects.

USPSTF Assessment

The USPSTF concludes that the evidence on routine screening for CKD in asymptomatic adults is lacking, and that the balance of benets and harms cannot be determined.

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Patient Population Under Consideration

shows that specic treatments for patients with diabetes reduce risk for advanced CKD. The American Diabetes Association recommends screening for CKD in all patients with diabetes. The USPSTF found very limited evidence about whether knowledge of CKD status in patients with isolated hypertension (those who do not also have diabetes or cardiovascular disease) helps in making treatment decisions. However, several organizations recommend screening patients who are being treated for hypertension, including the National Institutes of Healths Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.

Potential Harms

This recommendation applies to asymptomatic adults without diagnosed CKD. Testing for and monitoring CKD for the purpose of chronic disease management (including monitoring patients with diabetes or hypertension) are not covered by this recommendation.

Suggestions for Practice Regarding the I Statement

Potential Preventable Burden and Benets

Chronic kidney disease is very prevalent; in 2011, 11% of the U.S. general population had the condition. However, most affected persons have risk factors for CKD, particularly older age, diabetes, and hypertension. It is usually asymptomatic until its advanced stages. Although there is no evidence on the benets and harms of screening in the general population of asymptomatic adults, evidence

568 16 October 2012 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 157 Number 8

For adults without diabetes or hypertension, risk for CKD and subsequent adverse outcomes from it are small. How many persons with a positive screening test result who will be conrmed to have CKD is unknown. There are no studies on the benets of early treatment in persons without diabetes or hypertension. Persons who have positive results on a screening test but do not have CKD may experience the harms associated with interventions and treatments without the potential for benet.

Current Practice

Serum creatinine testing is widely done for various reasons in clinical practice, including chronic disease

www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by Rizka Mulya on 02/22/2013

Screening for CKD: USPSTF Recommendation Statement

Clinical Guideline

management for patients with hypertension and diabetes. Many patients with CKD stages 1 to 3 seem to have at least some testing in usual clinical care, probably for other conditions or in response to guidelines from other organizations.

Risk Assessment

No generally accepted risk assessment tool for CKD or risk for complications of CKD exists. Diabetes and hypertension are well-established risk factors with strong links to CKD. Other risk factors for CKD include older age, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and family history.

Screening Tests

older age, obesity, and family history. Chronic kidney disease is more prevalent in women (12.6%) than in men (9.7%) and is similar in white (11.6%) and African American (11.2%) adults (1, 2). African Americans are 3 to 5 times more likely to have end-stage renal disease than white Americans (3, 4). Chronic kidney disease is associated with several adverse health outcomes in several studies, including increased risk for death, cardiovascular disease, fractures, bone loss, infections, cognitive impairment, and frailty.

Scope of Review

Although evidence to recommend routine screening is insufcient, the tests often suggested for screening that are feasible in primary care include testing the urine for protein (micro- or macroalbuminuria) and testing the blood for serum creatinine to estimate GFR. No studies have evaluated the sensitivity and specicity of 1-time testing with either or both tests for diagnosis of CKD, dened as decreased kidney function or kidney damage persisting for at least 3 months.

Treatment

This is a new topic for the USPSTF and was nominated for consideration by several organizations. The USPSTF reviewed evidence on screening for CKD, including evidence on screening, accuracy of screening, early treatment, and harms of screening and early treatment.

Accuracy of Screening Tests

Treatment of early stages of CKD is generally targeted to comorbid conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, to reduce the risk for complications and progression of CKD. Treatments include blood pressure medications (particularly angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin IIreceptor blockers), lipid-lowering agents, and diet modication.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Research Needs and Gaps

Future research to dene the sensitivity and specicity of 1-time testing for CKD would help to clarify the usefulness of these tests and interpretation of their results. More research is needed to explore the reasons for and possible interventions to prevent the disproportionate progression to end-stage kidney disease in the African American population. More research is needed on the potential benets and harms of screening and early treatment of CKD in persons without diabetes or hypertension. Studies that evaluate the effect of screening for CKD in patients with hypertension but not diabetes would help to dene the benets and harms of screening in this risk group.

Although a 1-time creatinine-derived estimate of GFR highly correlates to a 1-time direct measurement of GFR, the USPSTF could not nd any studies on the accuracy of screening (with serum creatinine or urinary albumin) for CKD dened as impaired GFR or albuminuria that persists for at least 3 months (1, 2). A few studies provide some information about reliability and false-positive results. Intra-individual variability of urinary albumin is high; reported coefcients of variance estimates range from 30% to 50% (5). Body position, exercise, and fever can affect urinary albumin excretion (5). Although many groups recommend 1-time urinary albumin testing and calculation of a protein creatinine ratio, no standard for collection and measurement of urinary albumin or creatinine exists. A study using NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data reported that 37% of persons with microalbuminuria and a GFR of 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or greater did not have micro- or macroalbuminuria on repeated testing 2 months later (6). Another study reported that 59% of participants with diabetes and persistent microalbuminuria (dened by repeated abnormal protein creatinine ratios over a 2-year period) regressed to normal over a subsequent 6-year period (7).

Effectiveness of Early Detection and Treatment

DISCUSSION

Burden of Disease

Approximately 11% of Americans have an early form of CKD (1, 2). Most cases are asymptomatic; are identied in early stages; and are associated with diabetes, hypertension, or both. Medicare data show that 48% of patients with CKD (excluding end-stage renal disease) have diabetes, 91% have hypertension, and 46% have atherosclerotic heart disease (1, 2). Other reported risk factors include

www.annals.org

No studies directly evaluate the effectiveness of screening for CKD. Treatment of early stages of CKD is targeted to associated conditions, primarily using medications to control hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. There are few studies on early treatment of CKD stages 1 to 3 in persons without chronic diseases (such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease). Evidence shows that identication and treatment of CKD may affect management decisions or health outcomes in patients with established chronic disease, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension, but there is insufcient evidence that identication and early treatment of CKD in asymptomatic adults without these conditions results in improved health outcomes.

16 October 2012 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 157 Number 8 569

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by Rizka Mulya on 02/22/2013

Clinical Guideline

Screening for CKD: USPSTF Recommendation Statement

Potential Harms of Screening and Treatment

The USPSTF found no studies on the direct harms of screening for CKD. Potential harms of screening include adverse effects from venopuncture and psychological effects of labeling a person with CKD. The USPSTF found no studies on these potential harms. The most important potential for harm could occur because of false-positive test results. Patients could be falsely identied as having CKD and receive unnecessary treatment and diagnostic interventions, with their resultant harmful effects. The USPSTF found insufcient evidence to quantify the overall harms from false-positive test results. As discussed previously, several studies provide limited information about the potential frequency of false-positive test results. Convincing evidence shows that some harm occurs from medications used to treat comorbid medical conditions associated with early CKD, such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Although studies inconsistently report withdrawals or adverse effects by treatment group, commonly reported adverse effects of medications reviewed include cough with angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors; hypotension with antihypertension medications; edema with calcium-channel blockers; and hyperkalemia with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin IIreceptor blockers, and aldosterone antagonists (1, 2).

Estimate of Magnitude of Net Benefit

using urinary albumin and serum creatinine testing (9). The National Institutes of Healths Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure recommends that all persons diagnosed with hypertension should have urinalysis and serum creatinine testing; urine testing for albumin is optional (10).

From the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Rockville, Maryland.

Disclaimer: Recommendations made by the USPSTF are independent of the U.S. government. They should not be construed as an ofcial position of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Financial Support: The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary body.

The U.S. Congress mandates that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality support the operations of the USPSTF.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Disclosure forms from USPSTF mem-

bers can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConictOf InterestForms.do?msNumM12-1735.

Requests for Single Reprints: Reprints are available from the USPSTF

Web site (www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org).

References

1. Fink HA, Ishani A, Taylor BC, Greer NL, MacDonald R, Rossini D, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 13: Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment. Comparative Effectiveness Review 37. AHRQ Publication 11(12)-EHC075-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. 2. Fink HA, Ishani A, Taylor BC, Greer NL, MacDonald R, Rossini D, et al. Screening for, monitoring, and treatment of chronic kidney disease stages 1 to 3: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2012; 156:570-81. [PMID: 22508734] 3. Hsu CY, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG. Racial differences in the progression from chronic renal insufciency to end-stage renal disease in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2902-7. [PMID: 14569100] 4. Xue JL, Eggers PW, Agodoa LY, Foley RN, Collins AJ. Longitudinal study of racial and ethnic differences in developing end-stage renal disease among aged medicare beneciaries. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1299-306. [PMID: 17329578] 5. Miller WG, Bruns DE, Hortin GL, Sandberg S, Aakre KM, McQueen MJ, et al; National Kidney Disease Education Program-IFCC Working Group on Standardization of Albumin in Urine. Current issues in measurement and reporting of urinary albumin excretion. Clin Chem. 2009;55:24-38. [PMID: 19028824] 6. Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41: 1-12. [PMID: 12500213] 7. Perkins BA, Ficociello LH, Silva KH, Finkelstein DM, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. Regression of microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2285-93. [PMID: 12788992] 8. National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classication, and Stratication. 2002. Accessed at www.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guidelines_ckd/p9_approach .htm on 27 June 2012. 9. American Diabetes Association. Executive summary: standards of medical care in diabetes2012. Diabetes Care. 2012;35 Suppl 1:S4-S10. [PMID: 22187471] 10. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206-52. [PMID: 14656957]

www.annals.org

Although undiagnosed CKD in its early stages is common and there are potential benecial disease management interventions for persons with chronic diseases, the USPSTF found insufcient evidence on screening accuracy, benets of early treatment in the general population (that is, persons without chronic disease), and harms of screening. Therefore, evidence to assess the balance of benets and harms of screening for CKD in the general asymptomatic adult population is insufcient.

Response to Public Comment

A draft version of this recommendation statement was posted for public comment on the USPSTF Web site from 30 April through 29 May 2012. Most commenters agreed with the USPSTF statement. Several comments requested clarication that this recommendation does not apply to persons with diabetes or hypertension. This information was provided in several places in the statement.

RECOMMENDATIONS

OF

OTHER GROUPS

No guidelines from primary care organizations recommend screening all adults for CKD. The National Kidney Foundation recommends assessing risk for CKD in all patients and doing the following for those at increased risk: measure blood pressure, test serum creatinine levels, test urinary albumin levels, and examine urine for erythrocytes and leukocytes (8). The American Diabetes Association recommends annual screening of all persons with diabetes

570 16 October 2012 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 157 Number 8

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by Rizka Mulya on 02/22/2013

Annals of Internal Medicine

APPENDIX: U.S. PREVENTIVE SERVICES TASK FORCE

Members of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force at the time this recommendation was nalized are Virginia A. Moyer, MD, MPH, Chair (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas); Michael L. LeFevre, MD, MSPH, Co-Vice Chair (University of Missouri School of Medicine, Columbia, Missouri); Albert L. Siu, MD, MSPH, Co-Vice Chair (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, and James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Bronx, New York); Linda Ciofu Baumann, PhD, RN (University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin); Kirsten BibbinsDomingo, PhD, MD (University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California); Susan J. Curry, PhD (University of Iowa College of Public Health, Iowa City, Iowa); Mark Ebell, MD, MS (University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia); Glenn Flores, MD (University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, Texas); Adelita Gonzales Cantu, RN, PhD (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, Texas); David C. Grossman, MD, MPH (Group Health Cooperative, Seattle, Washington); Jessica Herzstein, MD, MPH (Air Products, Allentown, Pennsylvania); Joy Melnikow, MD, MPH (University of California, Davis, Sacramento, California); Wanda K. Nicholson, MD, MPH, MBA (University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina); Douglas K. Owens, MD, MS (Veteran Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, and Stanford University, Stanford, California); Carolina Reyes, MD, MPH (Virginia Hospital Center, Arlington, Virginia); and Timothy J. Wilt, MD, MPH (University of Minnesota Department of Medicine and Minneapolis Veteran Affairs Medical Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota). Ned Calonge, MD, MPH, a former USPSTF member, also contributed to the development of this recommendation. For a list of current USPSTF members, go to www .uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/members.htm.

Appendix Table 1. What the USPSTF Grades Mean and Suggestions for Practice

Grade A B Definition The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. Note: The following statement is undergoing revision. Clinicians may provide this service to selected patients depending on individual circumstances. However, for most individuals without signs or symptoms, there is likely to be only a small benefit from this service. The USPSTF recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. Suggestions for Practice Offer/provide this service. Offer/provide this service.

Offer/provide this service only if other considerations support offering or providing the service in an individual patient.

Discourage the use of this service.

I statement

Read the Clinical Considerations section of the USPSTF Recommendation Statement. If the service is offered, patients should understand the uncertainty about the balance of benefits and harms.

W-176 16 October 2012 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 157 Number 8

www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by Rizka Mulya on 02/22/2013

Appendix Table 2. USPSTF Levels of Certainty Regarding Net

Benefit

Level of Certainty* High Description The available evidence usually includes consistent results from well-designed, well-conducted studies in representative primary care populations. These studies assess the effects of the preventive service on health outcomes. This conclusion is therefore unlikely to be strongly affected by the results of future studies. The available evidence is sufficient to determine the effects of the preventive service on health outcomes, but confidence in the estimate is constrained by such factors as: the number, size, or quality of individual studies; inconsistency of findings across individual studies; limited generalizability of findings to routine primary care practice; and lack of coherence in the chain of evidence. As more information becomes available, the magnitude or direction of the observed effect could change, and this change may be large enough to alter the conclusion. The available evidence is insufficient to assess effects on health outcomes. Evidence is insufficient because of: the limited number or size of studies; important flaws in study design or methods; inconsistency of findings across individual studies; gaps in the chain of evidence; findings that are not generalizable to routine primary care practice; and a lack of information on important health outcomes. More information may allow an estimation of effects on health outcomes.

Moderate

Low

* The USPSTF denes certainty as likelihood that the USPSTF assessment of the net benet of a preventive service is correct. The net benet is dened as benet minus harm of the preventive service as implemented in a general primary care population. The USPSTF assigns a certainty level on the basis of the nature of the overall evidence available to assess the net benet of a preventive service.

www.annals.org

16 October 2012 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 157 Number 8 W-177

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by Rizka Mulya on 02/22/2013

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Part 9. Approach To Chronic Kidney Disease Using These GuidelinesDocumento8 paginePart 9. Approach To Chronic Kidney Disease Using These GuidelinesSudjarwo AntonNessuna valutazione finora

- Epidemiology Paper Final DraftDocumento8 pagineEpidemiology Paper Final Draftapi-583311992Nessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical GuidelineDocumento8 pagineClinical GuidelineAlvaro EnriquezNessuna valutazione finora

- Early Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocumento12 pagineEarly Chronic Kidney DiseaseDirga Rasyidin L100% (1)

- Blood Pressure Control For Diabetic Retinopathy (Review) : CochraneDocumento4 pagineBlood Pressure Control For Diabetic Retinopathy (Review) : CochraneArief VerditoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardio Prevention Intl Class (Armyn)Documento4 pagineCardio Prevention Intl Class (Armyn)Priyangga RakatamaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Kidney Disease in Children Clinical PresentationDocumento4 pagineChronic Kidney Disease in Children Clinical PresentationJendriella LaaeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Guideline Terbaru ACLFDocumento28 pagineGuideline Terbaru ACLFNovita ApramadhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Complications of DiabetesDocumento3 pagineComplications of Diabetesa7wfNessuna valutazione finora

- Renal Medicine 2: Early Recognition and Prevention of Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocumento14 pagineRenal Medicine 2: Early Recognition and Prevention of Chronic Kidney DiseaseAndreea GheorghiuNessuna valutazione finora

- Analgesic Use Parents Clan and Coffee Intake Are Three Independent Risk Factors of Chronic Kidney Disease in Middle and Elderly Aged Population ADocumento7 pagineAnalgesic Use Parents Clan and Coffee Intake Are Three Independent Risk Factors of Chronic Kidney Disease in Middle and Elderly Aged Population AJackson HakimNessuna valutazione finora

- Prevalence of Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease in The United StatesDocumento5 paginePrevalence of Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease in The United StateslionfairwayNessuna valutazione finora

- Self-Management Interventions For Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocumento13 pagineSelf-Management Interventions For Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisKikimariaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cost-Effectiveness - A Modeled AnalysisDocumento13 pagineCost-Effectiveness - A Modeled AnalysisAngelo Cardoso PereiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis and Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkDocumento41 pagineDiagnosis and Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network'-dooublleaiienn Itouehh IinNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline For The Management of High Blood Pressure in AdultsDocumento41 pagine2014 Evidence-Based Guideline For The Management of High Blood Pressure in AdultsJaime Gonzalvez ReyNessuna valutazione finora

- JNC 8Documento14 pagineJNC 8amiwahyuniNessuna valutazione finora

- JSC 130010Documento14 pagineJSC 130010Aqsha AmandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Geriatria Articulo EspecialDocumento15 pagineGeriatria Articulo EspecialBonchita BellaNessuna valutazione finora

- Adams, 2011Documento8 pagineAdams, 2011BrelianeloksNessuna valutazione finora

- Efficacy of Dietary Interventions in End-Stage Renal Disease Patients A Systematic ReviewDocumento13 pagineEfficacy of Dietary Interventions in End-Stage Renal Disease Patients A Systematic ReviewKhusnu Waskithoningtyas NugrohoNessuna valutazione finora

- Hta 8 JNCDocumento14 pagineHta 8 JNCLuis CelyNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis - PMCDocumento24 pagineGlobal Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis - PMCtrimardiyanaisyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study of a Patient with End Stage Renal DiseaseDocumento34 pagineCase Study of a Patient with End Stage Renal DiseaseSean Jeffrey J. FentressNessuna valutazione finora

- Diabcare 2021 Rwe CKDDocumento8 pagineDiabcare 2021 Rwe CKDanderson roberto oliveira de sousaNessuna valutazione finora

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Adherence To Glaucoma Follow-Up Visits in A County Hospital PopulationDocumento7 pagineRacial and Ethnic Disparities in Adherence To Glaucoma Follow-Up Visits in A County Hospital PopulationScott MuNessuna valutazione finora

- Dyslipidemia Awareness, Treatment, Control and Influence Factors Among Adults in The Jilin Province in China: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocumento9 pagineDyslipidemia Awareness, Treatment, Control and Influence Factors Among Adults in The Jilin Province in China: A Cross-Sectional Studytegar jhonessaNessuna valutazione finora

- JNC 8 SummaryDocumento14 pagineJNC 8 Summaryamm1101Nessuna valutazione finora

- JurdingDocumento7 pagineJurdingsiti hazard aldinaNessuna valutazione finora

- first-page-pdf (1) (2)Documento1 paginafirst-page-pdf (1) (2)Shakti PutradewaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mksap 15 General Internal MedicineDocumento181 pagineMksap 15 General Internal MedicineEzequiel Meneses100% (1)

- Prevalence, Risk Factors, Adherence and Non Adherence in Patient With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Prospective StudyDocumento7 paginePrevalence, Risk Factors, Adherence and Non Adherence in Patient With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Prospective StudyRanitaRahmaniarNessuna valutazione finora

- TX Adultos 2013Documento22 pagineTX Adultos 2013joao711Nessuna valutazione finora

- Retrospective CohortDocumento8 pagineRetrospective Cohortbonsa dadhiNessuna valutazione finora

- Alcoholic Liver DiseaseDocumento22 pagineAlcoholic Liver DiseaseVikramjeet SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- CPG Management of Chronic Kidney Disease in Adults June 2011Documento47 pagineCPG Management of Chronic Kidney Disease in Adults June 2011Kokoland KukusNessuna valutazione finora

- Insulin TherapyDocumento55 pagineInsulin TherapyShriyank BhargavaNessuna valutazione finora

- KDIGO Lipid Management in CKDDocumento13 pagineKDIGO Lipid Management in CKDIrma AwaliaNessuna valutazione finora

- jnc8 PDFDocumento14 paginejnc8 PDFRizki NovitasariNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care: Duaine D. Murphree, MD, and Sarah M. Thelen, MDDocumento9 pagineChronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care: Duaine D. Murphree, MD, and Sarah M. Thelen, MDTaufik Ali ZaenNessuna valutazione finora

- Nuclearoption For InsulinomaDocumento3 pagineNuclearoption For Insulinomadantheman123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Diabetes, Glycemic Control, and New-Onset Heart Failure in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery DiseaseDocumento6 pagineDiabetes, Glycemic Control, and New-Onset Heart Failure in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery DiseaseAMADA122Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Clinical Overview of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease A GuideDocumento12 pagineA Clinical Overview of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease A GuideAnindya RosmaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2013 Practice Guideline Long Term Managmentof Successful LTDocumento25 pagine2013 Practice Guideline Long Term Managmentof Successful LTDewanggaWahyuPrajaNessuna valutazione finora

- Labcomp FDocumento23 pagineLabcomp Fking peaceNessuna valutazione finora

- HTTPDocumento65 pagineHTTPAndreea SlabuNessuna valutazione finora

- Seminar: Ning Cheung, Paul Mitchell, Tien Yin WongDocumento13 pagineSeminar: Ning Cheung, Paul Mitchell, Tien Yin WongChandrahas ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Non-Cephalic Presentation in Late Pregnancy: EditorialsDocumento2 pagineNon-Cephalic Presentation in Late Pregnancy: EditorialsNinosk Mendoza SolisNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Intervention Aimed at ImprovingDocumento19 pagineNursing Intervention Aimed at ImprovingAnnis FathiaNessuna valutazione finora

- ADA Consenssus DM Eldery 2012Documento15 pagineADA Consenssus DM Eldery 2012Jason CarterNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study On Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocumento101 pagineCase Study On Chronic Kidney DiseaseZNEROL100% (6)

- Hypoglycemia in Diabetes: Pathophysiology, Prevalence, and PreventionDa EverandHypoglycemia in Diabetes: Pathophysiology, Prevalence, and PreventionNessuna valutazione finora

- Meeting the American Diabetes Association Standards of Care: An Algorithmic Approach to Clinical Care of the Diabetes PatientDa EverandMeeting the American Diabetes Association Standards of Care: An Algorithmic Approach to Clinical Care of the Diabetes PatientNessuna valutazione finora

- Guide to Health Maintenance and Disease Prevention: What You Need to Know. Why You Should Ask Your DoctorDa EverandGuide to Health Maintenance and Disease Prevention: What You Need to Know. Why You Should Ask Your DoctorNessuna valutazione finora

- Screening For Good Health: The Australian Guide To Health Screening And ImmunisationDa EverandScreening For Good Health: The Australian Guide To Health Screening And ImmunisationNessuna valutazione finora

- Outsmarting Diabetes: A Dynamic Approach for Reducing the Effects of Insulin-Dependent DiabetesDa EverandOutsmarting Diabetes: A Dynamic Approach for Reducing the Effects of Insulin-Dependent DiabetesValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (3)

- Diabetes Risks from Prescription and Nonprescription Drugs: Mechanisms and Approaches to Risk ReductionDa EverandDiabetes Risks from Prescription and Nonprescription Drugs: Mechanisms and Approaches to Risk ReductionNessuna valutazione finora

- Restoring Chronic Kidney Disease : Restoring, Preserving, and Improving CKD to Avoid DialysisDa EverandRestoring Chronic Kidney Disease : Restoring, Preserving, and Improving CKD to Avoid DialysisNessuna valutazione finora

- Gerd GuidelineDocumento8 pagineGerd GuidelineDewi AlwiNessuna valutazione finora

- WHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Documento160 pagineWHO Dengue Guidelines 2013Jason MirasolNessuna valutazione finora

- Lipid Profile in Bile and Serum of Cholelithiasis PatientsDocumento12 pagineLipid Profile in Bile and Serum of Cholelithiasis PatientsJagannadha Rao PeelaNessuna valutazione finora

- 00007Documento28 pagine00007Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Original ResearchDocumento23 pagineOriginal ResearchDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- 1750 1172 2 29Documento6 pagine1750 1172 2 29Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- 1750 1172 2 29Documento6 pagine1750 1172 2 29Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- 00003Documento21 pagine00003Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Editorial: Endoscopy For Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Choose WiselyDocumento2 pagineEditorial: Endoscopy For Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Choose WiselyDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Editorial: Cardiovascular Effects of Diabetes Drugs: Emerging From The Dark AgesDocumento2 pagineEditorial: Cardiovascular Effects of Diabetes Drugs: Emerging From The Dark AgesDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- 00004copdDocumento15 pagine00004copdDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- ACP 2012 - Oral Pharmacologic Treatment of Type 2 DMDocumento20 pagineACP 2012 - Oral Pharmacologic Treatment of Type 2 DMLidya ZhuangNessuna valutazione finora

- Incidence and Follow-Up of Braunwald Subgroups in Unstable Angina PectorisDocumento7 pagineIncidence and Follow-Up of Braunwald Subgroups in Unstable Angina PectorisDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Anemia PD PXKT JNTGDocumento10 pagineAnemia PD PXKT JNTGDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- 00005Documento12 pagine00005Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Aap Grand Rounds 2004 Neurology 15 - 2Documento6 pagineAap Grand Rounds 2004 Neurology 15 - 2Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- ReviewDocumento13 pagineReviewDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Apixaban For The Treatment of Acute Venous ThromboembolismDocumento10 pagineOral Apixaban For The Treatment of Acute Venous ThromboembolismDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Helicobacter Pylori - Negative Gastritis: Prevalence and Risk FactorsDocumento7 pagineHelicobacter Pylori - Negative Gastritis: Prevalence and Risk FactorsDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of An Angiotensin 2 Receptor Blocker Plus Diuretic Combination Drug in Chronic Heart Failure Complicated by HypertensionDocumento7 pagineEffects of An Angiotensin 2 Receptor Blocker Plus Diuretic Combination Drug in Chronic Heart Failure Complicated by HypertensionDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Stasi R j08Documento58 pagineStasi R j08Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of An Angiotensin 2 Receptor Blocker Plus Diuretic Combination Drug in Chronic Heart Failure Complicated by HypertensionDocumento7 pagineEffects of An Angiotensin 2 Receptor Blocker Plus Diuretic Combination Drug in Chronic Heart Failure Complicated by HypertensionDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Approach To ThrombocytopeniaDocumento8 pagineApproach To ThrombocytopeniaChairul Nurdin AzaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Aap Grand Rounds 2004 Neurology 15 - 2Documento6 pagineAap Grand Rounds 2004 Neurology 15 - 2Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pathogenesis of Immune Thrombocytopaenic Purpura: ReviewDocumento11 pagineThe Pathogenesis of Immune Thrombocytopaenic Purpura: ReviewNaomi ThamNessuna valutazione finora

- Unstable Angina and NSTEMI: The Early Management of Unstable Angina and non-ST-segment-elevation Myocardial InfarctionDocumento26 pagineUnstable Angina and NSTEMI: The Early Management of Unstable Angina and non-ST-segment-elevation Myocardial InfarctionCristian PeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1081 FullDocumento7 pagine1081 FullDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Case Report With Review of The LiteratureDocumento4 pagineOral Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Case Report With Review of The LiteratureDhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- A 07 V 43 N 1Documento4 pagineA 07 V 43 N 1Dhilah Harfadhilah FakhirahNessuna valutazione finora

- Practice: Pneumomediastinum and Subcutaneous Emphysema Associated With Pandemic (H1N1) Influenza in Three ChildrenDocumento3 paginePractice: Pneumomediastinum and Subcutaneous Emphysema Associated With Pandemic (H1N1) Influenza in Three ChildrenYandiNessuna valutazione finora

- Illness in GraphologyDocumento3 pagineIllness in Graphologymysticbliss100% (2)

- OstarineDocumento3 pagineOstarinehaydunn55Nessuna valutazione finora

- Med-Surg Nursing NotesDocumento232 pagineMed-Surg Nursing NotesMaria100% (4)

- AtropineDocumento4 pagineAtropineAnung RespatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases Imaging FindingsDocumento18 pagineProstate Cancer Bone Metastases Imaging FindingsAnonymous rna2NXPc9QNessuna valutazione finora

- The Importance of Endocrine GlandsDocumento4 pagineThe Importance of Endocrine GlandsMark Vincent Lacbain SaguinNessuna valutazione finora

- Electrostatic Field TherapyDocumento10 pagineElectrostatic Field Therapybooks sanNessuna valutazione finora

- Concept MapDocumento3 pagineConcept MapSophia PandesNessuna valutazione finora

- Health Vocabulary by Raccoony ZNODocumento10 pagineHealth Vocabulary by Raccoony ZNOДаша КошелєваNessuna valutazione finora

- Gouty Arthritis PathophysiologyDocumento1 paginaGouty Arthritis PathophysiologyKooksNessuna valutazione finora

- Thyroid WorkbookDocumento17 pagineThyroid Workbookpinkyhead99100% (1)

- Anatomy Mcqs With AnswersDocumento8 pagineAnatomy Mcqs With AnswersJk Flores67% (6)

- Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaDocumento9 pagineBenign Prostatic Hyperplasiamardsz100% (1)

- Cleric Spell List D&D 5th EditionDocumento9 pagineCleric Spell List D&D 5th EditionLeandros Mavrokefalos100% (2)

- AnsdDocumento12 pagineAnsdAlok PandeyNessuna valutazione finora

- Media 2Documento51 pagineMedia 2guugle gogleNessuna valutazione finora

- Case LabirinitisDocumento5 pagineCase LabirinitisAnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bioflavonoids Therapeutic PotentialDocumento15 pagineBioflavonoids Therapeutic PotentialCăplescu LucianNessuna valutazione finora

- Trade/Generic Name Classification Action of Medication Dosage/Route/ Frequency Indications For Use (Patient Specific)Documento16 pagineTrade/Generic Name Classification Action of Medication Dosage/Route/ Frequency Indications For Use (Patient Specific)lightzapNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 22: Young Adult Edelman: Health Promotion Throughout The Life Span, 8th EditionDocumento10 pagineChapter 22: Young Adult Edelman: Health Promotion Throughout The Life Span, 8th Editionmarvado10100% (1)

- Acupuncture Is A Form of Treatment or Energy Medicine That Involves Inserting Very Long Thin Needles Through A PersonDocumento4 pagineAcupuncture Is A Form of Treatment or Energy Medicine That Involves Inserting Very Long Thin Needles Through A PersonRonalyn Ostia DavidNessuna valutazione finora

- Brain Abscess (MEDSURG)Documento3 pagineBrain Abscess (MEDSURG)Yessamin Paith RoderosNessuna valutazione finora

- Nail Malformation Grade 8Documento30 pagineNail Malformation Grade 8marbong coytopNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal Health ReflectionDocumento7 paginePersonal Health Reflectionapi-284107243Nessuna valutazione finora

- Approach To HIV: Dr. Tejaswee BanavathuDocumento46 pagineApproach To HIV: Dr. Tejaswee BanavathuAbinash SwainNessuna valutazione finora

- Bad Trip Due To Anticholinergic Effect of CannabisDocumento2 pagineBad Trip Due To Anticholinergic Effect of CannabisRobert DinuNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug-Addiction-Biology ProjectDocumento37 pagineDrug-Addiction-Biology ProjectAhalya Bai SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- CA DIAGNOSTIC TEST Copy 1Documento11 pagineCA DIAGNOSTIC TEST Copy 1Ermita AaronNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity # 7 Fluid and Electrolyte Balance (WITH NCP)Documento15 pagineActivity # 7 Fluid and Electrolyte Balance (WITH NCP)Louise OpinaNessuna valutazione finora