Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Planned Brief Psychotherapy

Caricato da

Roci ArceDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Planned Brief Psychotherapy

Caricato da

Roci ArceCopyright:

Formati disponibili

220

Planned Brief Psychotherapy

session may lead to important insights into the broader psychosocial context of specific problematic behaviors (e.g., the presence of marital or work difficulties that exacerbate problem behaviors). BIBLIOGRAPHY

I . Baldwin JD, Baldwin J: Behavior Principles in Everyday Life. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1981. 2. Emmelkamp PMG: Behavior therapy with adults. In Bergin AE, Garfield SL (eds): Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 4th ed. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1994, pp 377427. 3. Emmelkamp PMG, Bourman TK, Scholing A: Anxiety Disorders. A Practitioners Guide. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, 1992. 4. Griest JH: Behavior therapy for obsessive compulsive disorders. J Clin Psycho1 55:60-68, 1994. 5. Noyes R: Treatments of choice for anxiety disorders. In Coryell W, Winokur G (eds): The Clinical Management of Anxiety Disorders. New York, Oxford University Press, 1991. 6. Sloane R, Staples F, Cristol A, et al: Psychotherapy Versus Behavior Therapy. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1975. 7. Wachtel P: Psychoanalysis and Behavior Therapy. New York, Basic Books, 1977.

43. PLANNED BRIEF PSYCHOTHERAPY

Mark A. Blais, Psy.D.

1. What is the natural course of psychotherapy? Despite the common perception that psychotherapy is a long-term, even timeless, enterprise, most of the existing data indicate that psychotherapy as it is practiced in the real world is a time-limited process. National outpatient psychotherapy utilization data from 1987 (obtained before the nationwide impact of managed care) reveals that 70% of psychotherapy users received 10 or fewer sessions, and only 15% received 21 or more sessions.I8 These data are highly consistent with findings from other utilizations studies. Clearly, most patients have a time-limited or brief psychotherapy experience. This chapter will help you deliver psychotherapy in an organized, planned, and thoughtful manner that more closely matches the natural course of psychotherapy.

2. How did brief psychotherapy develop?

Freud was one of the first practitioners of brief psychotherapy. A review of his early cases reveals that he treated many patients in a span of weeks to months rather than years. Over time, as psychoanalytic theory became more complex, the goals of psychoanalysis became more ambitious, and the length of treatment increased greatly. As early as 1925 this trend had become a concern to some. Alexander and French can be considered the true fathers of brief psychotherapy. Their book Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy outlined the first systematic attempt to develop a shorter and more efficient form of psychotherapy. Although not generally accepted in its time, this work laid the foundation for both psychoanalytic psychotherapy and modem brief psychotherapy. The modern era of brief treatment began with the work of Malan and of Sifneos. At present, brief psychoanalytic psychotherapies are supplemented by several other time-limited treatments, such as Becks cognitive therapy, Manns existential psychotherapy, and Klermans interpersonal treatment of depression.

3. How does brief psychotherapy differ from long-term psychotherapy? Four dimensions, considered common to all brief therapies, differentiate short-term from the more traditional long-term therapies: (1) the setting of a fixed time limit for the treatment, (2) holding to specific patient selection criteria, ( 3 ) using a treatment focus to limit the scope of the therapy, and (4) requiring increased activity by the therapist.

Planned Brief Psychotherapy

22 I

Summary o f Selected Planned Brief Psychotherapies

THERAPY SCHOOL NUMBER OF SESSIONS TYPE OF FOCUS PATIENT SELECTION

Analytic

Sifneos Anxiety suppressing Anxiety provoking Malan Davanloo 4-10 12-20 20-30 140 Crisis and coping Very narrow, Oedipal conflict and grief Very narrow, similar to Sifneos Resistance and suppressed anger Central issue and termination Automatic thoughts Patients interpersonal experience Interpersonal, developmental, and existential One borderline trait Fairly open, less healthy Very selective, top 2-l0% outpatients Responds to trial interpretation Less healthy, top 30% outpatients Broad patient selection (passive-dependent) Very broad, not psychotic Depressed patient, any level of health Broad range Borderline outpatients

~ ~

Existential

Mann

I2 exactly

Cognitive

Beck 1-14 12-16

Interpersonal

Klerman

Eclectic

Budman Leibovich

20-40

36-52

Adapted from Groves J: The short-term dynamic psychotherapies: An overview. In Ritan S (ed): Psychotherapy for the 90s. New York, Guilford Press, 1992.

Comparison of Brief and Long-Term Therapy

BRIEF LONG-TERM

Specific focused goals Specific time frame Emphasizes patient selection Here and now focus Attempts to restore psychologic functioning quickly The therapist is active and directive Uses between-session homework

Broad goals: insight and character change Time unlimited Down-plays patient selection Inner life, historical focus Techniques can cause increased psychological distress and temporary dysfunction Therapist is nondirective; therapy unfolds Is mostly limited to treatment hour

4. What is the best attitude for learning brief therapy?

There must be a willing suspension of disbelief and cynicism about brief treatment. Trainees are frequently taught that quick improvement is suspect and likely represents a transient flight into health. This can be a hard lesson to unlearn. Remember, brief therapy is not a fad, but rather a form of treatment developed and refined over many years, based upon clinical experience and treatment outcome studies. It must be recognized from the outset that therapy will end after a set number of sessions (or in some cases on a planned date). This can be difficult, particularly for therapists trained in long-term therapy, because this mindset has ramifications for all treatment decisions and requires a clinician to reconsider every intervention during the treatment. The brief therapist should accept (and expect) that patients will return to therapy periodically across their life span. This perspective allows a brief therapist to focus on the patients current difficulties rather than attempting a total lifelong cure.

222

Planned Brief Psychotherapy

5. For which patients is brief therapy appropriate?

Patient selection is an important (and distinguishing) part of brief therapy. Basically, patient selection is the art of finding the right patient with the right problem for brief psychotherapy. A two-session format is recommended to alleviate time pressure and allow the clinician to conduct a complete psychiatric evaluation while also assessing the appropriateness of the patient for brief psychotherapy.

6. Name some useful criteria for excluding or including a patient for brief psychotherapy. Exclusion criteria are best seen as categories (either the condition is present or absent); if any is present, the patient should be considered a poor candidate for brief treatment. Inclusion criteria are best viewed as dimensions, and as such they are likely present to a varying degree in every patient. The more of these qualities a patient has, the better the candidate for brief psychotherapy. Patient Selection Criteria for Brief Therapy

~ ~ ~~

Exclusion Criteria Actively psychotic Abusing substances At significant risk for self harm

Inclusion Criteria Moderate emotional distress Seeking relief from pain Able to articulate or accept specific cause or circumscribed problem as focus of treatment History of at least one positive mutual interpersonal relationship Functioning in at least one area of life Ability to commit to treatment contract

7. How does the brief therapist focus the treatment? Developing a treatment focus is probably the most misunderstood aspect of brief therapy. Many clinicians write about the focus i n a mysterious and circular manner. It often appears as if the whole success of the treatment rests on finding the one correct focus. Rather, what is needed for a successful brief treatment is the establishment of a functional focus; that is, a focus on which both the therapist and patient can agree to work.

8. How is a functional focus established? One powerful, straightforward technique is the Why now? question used by Budman and Gurman. It is applied by repeatedly asking the patient: Why did you come for treatment now? Why are you here now? Attention is directed to the current problem, rather than last weeks or tomorrows. (Try this simple technique a few times to see how effective it can be.) For example, a male patient (Pt) presents with significant depressive symptoms to a therapist (Th) at a walk-in clinic. Th: 1 hear from what you say that you are depressed and are feeling terrible, but I wonder what made you come in today? Pt: I cant take it any more. I know I need help. Th: You cant take it. What makes it impossible to take it now? Pt: Its getting too bad. I just cant take it any more. Th: It sounds like something happened recently that made you realize how bad things were. What made you realize that you had to get help now? Pt: I just felt so bad I couldnt go to work yesterday. I stayed home in bed all day. I never miss work. I must be falling apart. This line of questioning led to establishing the patients physical inactivity as a functional focus for treatment. As a result, his depression was successfully treated by increasing his physical activity. 9. Describe some typical functional foci. Budman and Gurman describe five common treatment foci: Losses past, present, or pending Development dyssynchronies; being out of step with expected developmental stages (Therapists should be able to identify with this because years of extended schooling and training usually keep life events such as marriage and children on hold.)

Planned Brief Psychotherapy

223

Interpersonal conflicts (usually repeated disappointments in important relationships) Symptomatic presentations and desire for symptom reduction Severe personality impairment (In brief therapy, one aspect of personality impairment can be selected as the focus of therapy.) Beginning brief therapists should use these five common foci to help organize their patients complaints and problems. The most important thing to remember is that you are not finding the focus, only a focus for the therapy.

10. How does the therapist complete the evaluation? Brief therapy is demanding for the therapist and patient. In addition to doing a full psychiatric interview, by the completion of the second evaluation session you need to have ( I ) determined whether the patient is suitable for brief treatment; (2) developed a functional focus; and (3) articulated a clear treatment contract. The patient and therapist must agree on a treatment contract. The contract identifies the treatment focus and spells out details, such as the number of sessions, procedure for missed appointments, and guidelines for post-termination contact. Brief therapy typically lasts 10-24 sessions, but may include as many as 50 sessions. (A 15-session treatment, not including the evaluation sessions, is a good length for a beginning brief therapist to start with). A flexible approach to missed appointments is recommended, and if the patient has a valid reason, the therapist should try to reschedule. if a session is missed without a valid reason, the missed session should be counted and the patients motivation should be explored, because this is resistance to treatment. 11. What is another advantage (besides the extra time) of a two-session evaluation? It allows an assessment of how the patient responds to the therapy (and therapist), providing important additional information about the appropriateness of brief treatment. Some form of intervention at the end of the first evaluation session is helpful in this regard. This initial intervention can be as simple as summarizing the patients problem and offering a tentative treatment focus or as complex as requiring the patient to fill out a psychological questionnaire. At the start of the second session, inquire about the intervention. If the patient responds positively (e.g., found it helpful to think of the problem in this new light; is interested in the psychological test results) and/or is feeling better, it is a sign that brief therapy may work. If the patient has not followed up on the intervention (e.g., did not think about the potential focus) or reacted angrily to it, it is a negative sign. 12. Can the functional focus change? No. Once a functional focus has been established, the therapist must maintain it. One way is by working consistently from within one style or orientation, of which there are basically three: (1) psychodynamic, (2) interpersonal, or (3) cognitive-behavioral. The one you use depends on your preference and, to some extent, your patients problem.

13. Describe the three approaches used in brief therapy. Most psychodynamic treatments are limited in their range of application and are appropriate for only a small percentage of clinic patients, typically those suffering from reactive or neurotic forms of depression (such as failure to grieve, fear of success and competition, and triangular, conflicted love relationships). These are demanding treatments for the therapist to undertake and require that the patient be able to tolerate considerable affective arousal. Brief interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) was developed by Klerman and colleagues specifically to treat depression. It is a highly formalized (manualized) treatment often used in research studies. It can be considered a mix of psychoeducation and supportive therapy. In IPT, the patients symptoms are explained (psychoeducation) and interpersonal interactions, expectations, and experiences are explored. IPT seeks to clarify what the patient wants to receive from relationships and helps patients develop necessary social-interpersonal skills. No effort is made to understand the deeper unconscious meaning of the patients social interactions or desires.

224

Planned Brief Psychotherapy

The cognitive-behavioral therapies, like Becks, are more broadly applicable, both in the percentage of patients who can benefit and the range of problems that can be treated. These therapies aim at bringing the patients autonomic (pre-conscious) thoughts into awareness and demonstrating how these thoughts maintain negative behaviors and feelings.

14. Are all three approaches employed simultaneously? No. A minimal, thoughtful amount of mixing of techniques from different therapy styles is acceptable. Therapeutic flexibility is necessary in brief treatment. It is important, however, to conceptualize and work predominantly from within one orientation to keep treatment focused and clear. Especially avoid uncritical wholesale mixing of styles and orientations, because such wild treatment confuses and disappoints both the therapist and patient.

15. What does it mean to be an active therapist? Completing a psychotherapy in 12-15 sessions requires sustained activity on the part of the therapist to maintain treatment focus and move the therapy process forward. The brief therapist works to structure every session, thereby increasing productivity.

The Active Therapist

Structure each session Give homework assignments Develop and use the working alliance Limit silences and vagueness Use confrontation and clarification Quickly address negative and overly positive transference Limit regression Use supervision

16. Discuss important factors for the active therapist in structuring sessions. Starting each session with a summary of important material from the last session and restating the treatment focus organizes therapy and keeps the treatment on track. Giving homework to the patient to be completed between sessions helps increase the impact of therapy on the patients current life and situation and monitor the patients motivation for change. If the patient does not complete the homework, the motivation for change must be explored. The working alliance between therapist and patient must be developed quickly. It is frequently invoked to return the patient to the treatment focus. Patients may attempt to escape the anxiety inherent in brief therapy by bringing up interesting but diverting material. The therapist should meet such tactics with reminders of the agreed-upon focus (thus invoking the working alliance) and queries about how the new material relates to it. Prolonged silences (by either the therapist or patient) are considered unproductive in brief therapy and also are quickly confronted as resistance. The brief therapist must know how to limit regression. Two useful techniques are (1) organizing interpretations about events in the here and now, using either the therapy relationship or the patients current life situation, rather than around early developmental traumas; and (2) moving the patient away from feelings and into thoughts-What are you thinking rather than What are you feeling? Regressions within sessions are permitted and even encouraged in some short-term work. For example, it is quite common, when employing a treatment modeled after that of Sifneos, to keep a patient focused on an anxiety-provoking conflict despite mild confusion or panic. 17. What are two valuable tools in brief therapy? The brief therapist makes heavy use of confrontation and clarification. Confrontation helps the patient recognize when he or she is avoiding or resisting the treatment focus, usually as a result of anxiety. Clarification techniques are used whenever the patient is communicating in a vague or incomplete manner. Usually the therapist asks for specific examples of unclear situations or feelings. 18. How does transference manifest in brief therapy? Regardless of the style of therapy you employ (psychodynamic, cognitive, or interpersonal) patients inevitably react to some of your interventions based on their past experiences. When such

Planned Brief Psychotherapy

225

reactions are negative (You always criticize me) or excessively positive (You know me better than anyone on earth), they must be explored and interpreted quickly. Rapid attention can help keep the patients transference under control and reduce the likelihood of it becoming a major resistance to treatment.

19. Is supervision unnecessary due to the short-term nature of this type of treatment? As in all psychotherapy, supervision is important in both learning and practicing brief psychotherapy. Supervision by an experienced colleague provides an excellent vehicle for beginning therapists. More advanced practitioners find that some form of ongoing supervision, either formal or informal, helps maintain the treatment focus and aids in identifying subtle, but often important, changes in the patients manner. Such subtle changes can represent the first signs of transference.

20. What are the phases of brief therapy? The initial phase includes evaluating and assessing patient appropriateness for brief therapy, selecting a treatment focus, and establishing the main treatment orientation. For the patient this phase is usually accompanied by slight symptom reduction and mildly positive transference. Both of these factors help with the quick development of a working alliance. In the middle phase, the work gets more difficult. Typically the patient becomes concerned about the time limit and, in addition to the treatment focus, issues of dependency become important. The patient often feels worse, and the therapists faith in the treatment process is tested. The early middle phase of brief therapy can be particularly hard for the therapist, who must be active in sustaining treatment focus, keeping the patient working, and countering patient skepticism while projecting optimism. Good supervision is invaluable during this phase for the beginning brief therapist. In the termination phase, therapy tends to settle down. The patient accepts that treatment will end as planned and that symptoms will decrease. Now, in addition to the treatment focus, post-therapy plans and the patients feelings about termination are explored. Among the most common termination problems is the introduction of new material by the patient. The therapist may be tempted to explore the new information and extend the therapy. This is usually a mistake, because the patient likely is attempting to avoid the treatment focus, and in most cases the treatment should end as planned.

21. How do I handle post-treatmentcontact with the patient? This difficult question must be answered individually by each therapist. During training, the beginning therapist should have the experience of handling the intense feelings (both his or her own and the the patients) that accompany the termination of a treatment in which there will be 110 posttherapy contact. This teaches the therapist how to deal openly with these powerful and important feelings. In ongoing practice, however, it is important to encourage patients to return for treatment when new difficulties develop, and to foster the understanding that help is available if needed. Patient care should be guided by the understanding that Therapy is for living and not vice versa. The brief psychotherapist practices as a primary care physician, available to help patients with (psychological) troubles or crises that develop. 22. How does brief psychotherapy relate to managed care? In a managed care environment, payors are encouraging the use of shorter treatments such as planned brief psychotherapy. However, managed mental health care and brief psychotherapy are not identical. Managed health care is primarily concerned with controlling cost. Planned brief psychotherapy represents a clinically proven procedure for helping some patients in need of psychiatric services. To be administered properly, brief psychotherapy must be based on clinical, not financial, considerations. Although many patients covered by managed care contracts benefit from brief psychotherapy, not all patients are appropriate. Many variables are involved in selecting patients for brief psychotherapy-but mental health insurance coverage is not one of them. Finally, therapy that is considered brief for clinical work (i.e., 15-20 sessions) may be considered too long by managed care companies, who often suggest 6-8 sessions.

226

Marital and Family Therapies

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Alexander F, French T Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. New York, The Ronald Press, 1946. la. Beck AT: Cognitive therapy for depression and panic disorder. Western J Med 151:9-89, 1989. 2. Beck S, Greenberg R: Brief cognitive therapies. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2: 1 1-22, 1979. 2a. Book H E How to Practice Brief Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: The Core Conflictual Relationship Theme Method. Washington, DC, American Ps~chologic~l Association Press, 1998. 3. Budman S, Gurman A: Theory and Practice of Brief Therapy. New York, The Guilford Press, 1988. 4. Burk J, White H, Havens L: Which short-term therapy? Arch Gen Psychiatry 36: 177-1 86, 1989. 5. Davanloo H: Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. New York, Jason Aronson, 1980. 6. Ferenczi S, Rank 0: The Development of Psychoanalysis. New York, Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company, 1925. 7. Flegenheimer W: History of brief psychotherapy. In Horner A (ed): Treating the Neurotic Patient in Brief Psychotherapy. New Jersey, Jason Aronson, 1985, pp 7-24. 8. Goldin V Problems of technique: In Horner A (ed): Treating the Neurotic Patient in Brief Psychotherapy. New Jersey, Jason Aronson, 1985, pp 56-74. 9. Groves J: Essential Papers on Short-Term Dynamic Therapy. New York, New York University Press, 1996. 10. Groves J: The short-term dynamic psychotherapies: An overview. In Rutan S (ed): Psychotherapy for the 90s. New York, Guilford Press, 1992. 1 I . Hall M, Arnold W, Crosby R: Back to basics: The importance of focus selection. Psychotherapy 4578-584, 1990. 12. Horner A : Principles for the therapist. In Horner A (ed): Treating the Neurotic Patient in Brief Psychotherapy. New Jersey, Jason Aronson, 1985, pp 76-85. 13. Horath A, Luborsky L: The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psycho1 61:561-573, 1993. 14. Klerman G, Weissman M, Rounsaville B, Chevron E: Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, Basic Books, 1984. 15. Leibovich M: Short-term psychotherapy for the borderline personality disorder. Psychother Psychosom 35:257-264, 1981. 16. Malan D: The Frontier of Brief Psychotherapy. New York, Plenum Medical Book Company, 1976. 17. Mann J: Time-Limited Psychotherapy. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1973. 18. Olfson M, Pincus HA: Outpatient psychotherapy in the United States. 11: Patterns of utilization. Am J Psychiatry 151:1289-1294, 1994. 19. Sifneos P: Short-Term Anxiety Provoking Psychotherapy: A Treatment Manual. New York, Basic Books, 1992.

44. MARITAL AND FAMILY THERAPIES

Margaret Roath, M.S.W., LCSW

1. What a r e marital and family therapies? Marital and family therapies are therapeutic modalities whose focus of assessment and treatment is on the relationship, not on the individual. Assessment includes gathering data related to the following areas: History of the relationship Communication patterns, both Goals of the individuals in the relationship constructive and destructive Coping mechanisms which have been Description of the strengths of unsuccessful the relationship Precipitant for seeking therapy--why now? Unmet needs of the individuals or what changed? in the relationship Assessment of the precipitant for seeking marital or family therapy is especially important in determining the relationship equilibrium-which may have worked previously for all members of the relationship, but is now out of balance. The precipitant might be a change in external circumstances or a change within an individual that is affecting the relationship.

9

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Chapter 7-Brief Psychodynamic Therapy: BackgroundDocumento54 pagineChapter 7-Brief Psychodynamic Therapy: BackgroundKarenHNessuna valutazione finora

- Coping with Depression: A Guide to What Works for Patients, Carers, and ProfessionalsDa EverandCoping with Depression: A Guide to What Works for Patients, Carers, and ProfessionalsNessuna valutazione finora

- Brief Dynamic Therapy: Fathima P MDocumento18 pagineBrief Dynamic Therapy: Fathima P MFathima MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Principles of Intensive PsychotherapyDa EverandPrinciples of Intensive PsychotherapyValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (3)

- Recent Advances in Social Skills Training For Schizophrenia PDFDocumento12 pagineRecent Advances in Social Skills Training For Schizophrenia PDFMarco Macavilca CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Multimodal Treatment of Acute Psychiatric Illness: A Guide for Hospital DiversionDa EverandMultimodal Treatment of Acute Psychiatric Illness: A Guide for Hospital DiversionNessuna valutazione finora

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy For Depression Ipt Competency FrameworkDocumento38 pagineInterpersonal Psychotherapy For Depression Ipt Competency FrameworkIoana Boca100% (1)

- Goals of TherapyDocumento4 pagineGoals of TherapyMuneebah Abdullah0% (1)

- CBT for Schizophrenia: Evidence-Based Interventions and Future DirectionsDa EverandCBT for Schizophrenia: Evidence-Based Interventions and Future DirectionsCraig SteelValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- A Filled-In Example: Schema Therapy Case Conceptualization FormDocumento10 pagineA Filled-In Example: Schema Therapy Case Conceptualization FormKarinaNessuna valutazione finora

- States and Processes for Mental Health: Advancing Psychotherapy EffectivenessDa EverandStates and Processes for Mental Health: Advancing Psychotherapy EffectivenessNessuna valutazione finora

- 1983 - The Brief Symptom Inventory, An Introductory ReportDocumento11 pagine1983 - The Brief Symptom Inventory, An Introductory ReportBogdan BaceanuNessuna valutazione finora

- Counseling People With Early-Stage Alzheimer's Disease: A Powerful Process of Transformation (Yale Counseling People Excerpt)Documento6 pagineCounseling People With Early-Stage Alzheimer's Disease: A Powerful Process of Transformation (Yale Counseling People Excerpt)Health Professions Press, an imprint of Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.Nessuna valutazione finora

- MSE and History TakingDocumento17 pagineMSE and History TakingGeetika Chutani18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Defense Mechanisms HandoutDocumento1 paginaDefense Mechanisms HandoutV_FreemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychopharmacology: Borderline Personality DisorderDocumento7 paginePsychopharmacology: Borderline Personality DisorderAwais FaridiNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychotherapy Notes Sample GeriatricDocumento2 paginePsychotherapy Notes Sample GeriatricKadek Mardika0% (3)

- 5Ps FormulationDocumento8 pagine5Ps FormulationNguyễn Phạm Minh NgọcNessuna valutazione finora

- Cognitive Behavior Theraphy PDFDocumento20 pagineCognitive Behavior Theraphy PDFAhkam BloonNessuna valutazione finora

- Fundamentals To Clinical PsychologyDocumento6 pagineFundamentals To Clinical PsychologySurabhi RanjanNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Interview Made EasyDocumento107 pagineClinical Interview Made EasyDr Nader Korhani100% (1)

- Diagnosis, Case Conceptualization and Treatment PlanningDocumento14 pagineDiagnosis, Case Conceptualization and Treatment PlanningTrini Atters100% (5)

- A Primer For PsychotherapistsDocumento136 pagineA Primer For PsychotherapistsrichuNessuna valutazione finora

- PTSD and Cognitive Processing Therapy Presented by Patricia A. Resick, PHD, AbppDocumento28 paginePTSD and Cognitive Processing Therapy Presented by Patricia A. Resick, PHD, AbppDardo Arreche100% (2)

- Kring Abnormal Psychology Chapter 5 Mood Disorders NotesDocumento14 pagineKring Abnormal Psychology Chapter 5 Mood Disorders NotesAnn Ross FernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- GC 601 - Carl Jung's Analytical PsychologyDocumento3 pagineGC 601 - Carl Jung's Analytical PsychologyLeonard Patrick Faunillan BaynoNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivational Therapy (Or MT) Is A Combination ofDocumento2 pagineMotivational Therapy (Or MT) Is A Combination ofRumana AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Case Formulation - Major Depressive DisorderDocumento8 pagineSample Case Formulation - Major Depressive DisorderCherry Mae TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- ACT For Psychosis Workshop BABCP 2008 Eric Morris Gordon Mitchell Amy McArthurDocumento11 pagineACT For Psychosis Workshop BABCP 2008 Eric Morris Gordon Mitchell Amy McArthurjlbermudezc100% (1)

- Psychotherapy For BPDDocumento5 paginePsychotherapy For BPDJuanaNessuna valutazione finora

- CV Vivek Benegal 0610Documento16 pagineCV Vivek Benegal 0610bhaskarsg0% (1)

- Case Conceptualization PDFDocumento11 pagineCase Conceptualization PDFluis_bartniskiNessuna valutazione finora

- Tat (1) (1) - 1Documento24 pagineTat (1) (1) - 1Seerat FatimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychotherapy With The Dying PatientDocumento21 paginePsychotherapy With The Dying PatientAdelina RotaruNessuna valutazione finora

- A Manual For MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy in The Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress DisorderDocumento68 pagineA Manual For MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy in The Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress DisorderGouL 11Nessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Brief Psychodynamic TherapyDocumento2 pagineTypes of Brief Psychodynamic TherapyJasroop MahalNessuna valutazione finora

- Syl 1415 Psychodynamic PsychotherapyDocumento3 pagineSyl 1415 Psychodynamic PsychotherapyMaBinNessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence Based Psychological InterventionsDocumento177 pagineEvidence Based Psychological InterventionsGretel PsiNessuna valutazione finora

- Rehabilitation Psychology ChapterDocumento48 pagineRehabilitation Psychology Chapterprince razzoukNessuna valutazione finora

- Prodromal SchizophreniaDocumento13 pagineProdromal SchizophreniadizhalfaNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Skills Training For SchizophreniaDocumento122 pagineSocial Skills Training For SchizophreniaSilvana KurianNessuna valutazione finora

- RP1 Five Stagesof ChangeDocumento5 pagineRP1 Five Stagesof ChangeFarah BahromNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Interview and ObservationDocumento47 pagineClinical Interview and Observationmlssmnn100% (1)

- Diagnostic FormulationDocumento8 pagineDiagnostic FormulationAnanya ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Provisional Diagnosis: Differential DiagnosesDocumento7 pagineProvisional Diagnosis: Differential Diagnoseshernandez2812Nessuna valutazione finora

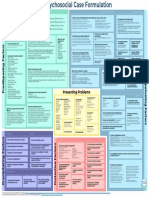

- Biopsychosocial Case Formulation Cheatsheet - No LinksDocumento1 paginaBiopsychosocial Case Formulation Cheatsheet - No LinksAi Hwa Lim100% (1)

- Psychodynamic Diagnostic ManualDocumento6 paginePsychodynamic Diagnostic Manualas9as9as9as9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Offensive Deffensive - Stress and DTDocumento5 pagineOffensive Deffensive - Stress and DTCristina EneNessuna valutazione finora

- Individual PsychotherapyDocumento48 pagineIndividual PsychotherapySanur0% (1)

- Manual Psicoger SparDocumento430 pagineManual Psicoger Sparpereiraboan9140Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case Conceptualization Counselor's Name - DateDocumento1 paginaCase Conceptualization Counselor's Name - DateFarisha Assila100% (1)

- Interview Method in AssessmentDocumento13 pagineInterview Method in AssessmentAnanya100% (2)

- Psycho Dynamic Psychotherapy A SystematicDocumento13 paginePsycho Dynamic Psychotherapy A SystematicJohn DeLongNessuna valutazione finora

- ADVANCE SKILLS Supportive Psychotherapy 3ADocumento5 pagineADVANCE SKILLS Supportive Psychotherapy 3AKiran MakhijaniNessuna valutazione finora

- History TakingDocumento34 pagineHistory TakingSulieman MazahrehNessuna valutazione finora

- Depersonalization ReportDocumento4 pagineDepersonalization ReportLeslie Vine DelosoNessuna valutazione finora

- Impulsive DisordersDocumento21 pagineImpulsive DisordersAli B. SafadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Psy460 Ch07 HandoutDocumento6 paginePsy460 Ch07 HandoutDev PrashadNessuna valutazione finora

- I. Approach To Clinical Interviewing and DiagnosisDocumento6 pagineI. Approach To Clinical Interviewing and DiagnosisRoci ArceNessuna valutazione finora

- Sedative-Hypnotic DrugsDocumento8 pagineSedative-Hypnotic DrugsRoci ArceNessuna valutazione finora

- Encopresis and EnuresisDocumento10 pagineEncopresis and EnuresisRoci ArceNessuna valutazione finora

- Antianxiety AgentsDocumento4 pagineAntianxiety AgentsRoci ArceNessuna valutazione finora

- Mood-Stabilizing AgentsDocumento9 pagineMood-Stabilizing AgentsRoci ArceNessuna valutazione finora

- Group TherapyDocumento6 pagineGroup TherapyRoci ArceNessuna valutazione finora

- DeliriumDocumento5 pagineDeliriumRoci ArceNessuna valutazione finora

- Impulse-Control DisordersDocumento6 pagineImpulse-Control DisordersRoci ArceNessuna valutazione finora

- DementiaDocumento6 pagineDementiaRoci ArceNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S0196655316001693 MainDocumento3 pagine1 s2.0 S0196655316001693 MainSandu AlexandraNessuna valutazione finora

- ACSM's Complete Guide To Fitness & Health, 2nd EditionDocumento449 pagineACSM's Complete Guide To Fitness & Health, 2nd EditionRitaMata95% (22)

- MM 010Documento6 pagineMM 010worksheetbookNessuna valutazione finora

- Nutritional Assessment Among Patient With Hemodialysis in Ramallah Health ComplexDocumento42 pagineNutritional Assessment Among Patient With Hemodialysis in Ramallah Health ComplexYousef JafarNessuna valutazione finora

- Spindler 2021 CVDocumento5 pagineSpindler 2021 CVapi-550398705Nessuna valutazione finora

- Physical Examination ScoliosisDocumento7 paginePhysical Examination Scoliosisyosua_edwinNessuna valutazione finora

- RA For Installation & Dismantling of Loading Platform A69Documento8 pagineRA For Installation & Dismantling of Loading Platform A69Sajid ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- MSDS Addmix 700Documento6 pagineMSDS Addmix 700Sam WitwickyNessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum VitaeDocumento2 pagineCurriculum VitaeHORT SroeuNessuna valutazione finora

- Sexual Reproductive Health Program FGM and Child Early/Forced Marriage (FGM and CEFM) ProjectDocumento4 pagineSexual Reproductive Health Program FGM and Child Early/Forced Marriage (FGM and CEFM) ProjectOmar Hassen100% (1)

- ResearchDocumento71 pagineResearchAngeline Lareza-Reyna VillasorNessuna valutazione finora

- Caregiving NC II - CBCDocumento126 pagineCaregiving NC II - CBCDarwin Dionisio ClementeNessuna valutazione finora

- THESIS PRESENTATION - Final PDFDocumento24 pagineTHESIS PRESENTATION - Final PDFPraveen KuralNessuna valutazione finora

- Mmse Mna GDS PDFDocumento4 pagineMmse Mna GDS PDFSoleil MaxwellNessuna valutazione finora

- 3a. Antisocial Personality DisorderDocumento19 pagine3a. Antisocial Personality DisorderspartanNessuna valutazione finora

- Population Pyramid IndiaDocumento4 paginePopulation Pyramid India18maneeshtNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Exam Review NutritionDocumento9 pagineFinal Exam Review Nutritionjenm1228Nessuna valutazione finora

- Omar Lunan Massage ResumeDocumento2 pagineOmar Lunan Massage Resumeapi-573214817Nessuna valutazione finora

- Traumatic Brain InjuryDocumento50 pagineTraumatic Brain InjuryDavide LeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Rickets of Vitamin D DeficiencyDocumento70 pagineRickets of Vitamin D Deficiencyapi-19916399Nessuna valutazione finora

- PHINMA Education NetworkDocumento3 paginePHINMA Education NetworkMichelle Dona MirallesNessuna valutazione finora

- Acetylcysteine 200mg (Siran, Reolin)Documento5 pagineAcetylcysteine 200mg (Siran, Reolin)ddandan_2Nessuna valutazione finora

- 30 Days To Better Habits - Examples DatabaseDocumento9 pagine30 Days To Better Habits - Examples DatabaseAlysia SiswantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Infection Control Competency QuizDocumento7 pagineInfection Control Competency QuizLoo DrBradNessuna valutazione finora

- Consultation and Liaison Consultation and Liaison Psychiatry (PDFDrive)Documento70 pagineConsultation and Liaison Consultation and Liaison Psychiatry (PDFDrive)mlll100% (1)

- StillbirthDocumento4 pagineStillbirthTubagus Siswadi WijaksanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Holidaybreak CS PDFDocumento2 pagineHolidaybreak CS PDFandrea94Nessuna valutazione finora

- Children, Cell Phones, and Possible Side Effects Final DraftDocumento5 pagineChildren, Cell Phones, and Possible Side Effects Final DraftAngela Wentz-MccannNessuna valutazione finora

- Skill 10 Chest Tube Care and Bottle ChangingDocumento3 pagineSkill 10 Chest Tube Care and Bottle ChangingDiana CalderonNessuna valutazione finora

- Tourist Safety and SecurityDocumento166 pagineTourist Safety and SecurityGiancarlo Gallegos Peralta100% (1)

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Da EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Valutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsDa EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNessuna valutazione finora

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDDa EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (3)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDa EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (404)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDa EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (32)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDa EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (82)

- Dark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingDa EverandDark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1138)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDa EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeValutazione: 2 su 5 stelle2/5 (1)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDa EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (4)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDa EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeDa EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (254)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaDa EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Da EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (110)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesDa EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (1412)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDa EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (6)

- Hearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIDa EverandHearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (20)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsDa EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (170)

- Empath: The Survival Guide For Highly Sensitive People: Protect Yourself From Narcissists & Toxic Relationships. Discover How to Stop Absorbing Other People's PainDa EverandEmpath: The Survival Guide For Highly Sensitive People: Protect Yourself From Narcissists & Toxic Relationships. Discover How to Stop Absorbing Other People's PainValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (95)

- The Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeDa EverandThe Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (4)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsDa EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (39)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryDa EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (46)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessDa EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (328)

- Summary: Thinking, Fast and Slow: by Daniel Kahneman: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDa EverandSummary: Thinking, Fast and Slow: by Daniel Kahneman: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (61)

- How to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingDa EverandHow to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingValutazione: 1 su 5 stelle1/5 (1)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisDa EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (8)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsDa EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNessuna valutazione finora