Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Theory BasedChange

Caricato da

Mahathir FansuriCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Theory BasedChange

Caricato da

Mahathir FansuriCopyright:

Formati disponibili

MILBREY W.

MCLAUGHLIN and DANA MITRA

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY: GOING DEEPER, GOING BROADER

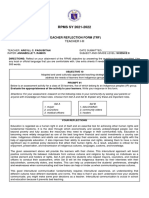

ABSTRACT. This article examines the questions of sustaining and extending theorybased educational change reforms, which are designed by laboratories outside of schools and whose motivating theoretical base assumes change in elemental aspects of classroom practice. This article denes sustainability of theory-based reform as more than maintaining current implementation, rather as deepening reforms in ways that allow for exible response to changes in student, curricular, and school contexts. It draws upon ve years of research in schools and classrooms engaged in one of three theory-based reforms to discuss ve essential factors affecting sustainability: resources, reformers learning, knowledge of the rst principles of the reform and the support of a community of practice, the principal, and the district. This article then turns to scaling up. Rather than merely replicating structures, extending theory-based reform to new sites requires building compatibility between the normative base of the reform with that in the classrooms, schools and districts in which they are growing as well as the capacity of the classroom, school, and district to see it through. This article suggests three main factors that reform founders must focus upon to scale up their reforms attention to site selection, a proactive stance toward district contexts, and planned transfer of authority. The article concludes that issues of invention, implementation, sustainability, and scale occur simultaneously when going deeper and broader with theory-based change.

When are you going to stop drilling, and start pumping? This question captures a Texas philanthropists exasperation with the lack of payoff he saw from a steady stream of investments in educational research and development. We take up the Texans concern to examine the issues of sustaining and extending educational reforms. More specically, we focus on payoff issues associated with a particular type of reform, theorybased change those R&D efforts that aim to change elemental aspects of classroom practice.

T HEORY- BASED R EFORMS AND T HIS R ESEARCH Theory-based reforms present particular challenges to practitioners and implementing systems. One is their motivating theoretical base, which establishes core principles or norms of practice and denes the change. This feature contrasts with reforms that engage only surface curriculum

Journal of Educational Change 2: 301323, 2001. 2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

302

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

or discrete materials and do not implicate the theoretical foundation of classroom practice. Theory-based reforms typically are developed in university laboratories and take practical form as they move into the natural settings of schools. Reformers often are external not only to the school, but to the system, and so may have little direct knowledge of the classrooms into which their theories will enter. Theory-based reforms require signicant teacher learning and contextualization if they are to change teaching and learning in signicant, sustained ways. Theory-based change thus entails three main ideas: core principles, the external development of the reform initially, co-invention and exible implementation in practice. We base this examination of sustaining and extending theory-based change on approximately ve years of research involving three reform efforts that are based on promising theories of learning and instruction: Fostering a Community of Learners, Schools for Thought and the Child Development Project.1 Fostering a Community of Learners (FCL) is an elementary school reform that promotes critical thinking and reection through disciplinary research by utilizing engineered curricula units, reciprocal teaching focusing on research-share-perform, designed assessments, participant structures for classroom management and community-building, and one-on-one coaching.2 Schools for Thought (SFT) integrates FCL with two other cognitively based approaches to learning, Vanderbilts Adventures of Jasper Woodbury to teach mathematical problem solving with complex, realistic problems and the CSILE Project (Computer Supported Intentional Learning Environments)3 for computer-based problem solving.4 The Child Development Project (CDP) is an elementary-school program that promotes social and ethical development in children. It emphasizes building a caring community of learners, the social and ethical as well as intellectual dimensions of learning, using a constructivist approach to teaching and learning, and developing in students the intrinsic motivation to learn.5 Each R&D effort aims to put into practice principles constructed from theories of cognition and learning (FCL and SFT) and of child intellectual and social development (CDP). Though the reforms differ in particular activities and emphases, each advances similar ideas about learner-centered instruction and active engagement of students in their own learning. The school sample for this research consisted of fteen schools, located in eight districts, representing the three reform efforts: FCL (two districts, three schools); SFT (one district, four schools); CDP (three districts, six schools. All FCL, CDP sites were public elementary schools, all basically self-contained classrooms. SFT sites were initially middle schools, with

TABLE I. Characteristics of the reforms Fostering a Community of Learners (FCL) Elementary Promotes multiple forms of literacy by engaging students in generating own research. Focus is to promote critical thinking and reection embedded in deep disciplinary content knowledge. Sustained, interdependent individual and group research a dialogic base founded on deliberately distributed expertise; engineered curricula units; reciprocal teaching; emphasis on authentic materials. Initially curricular units that connect technology with in-depth examination of authentic problems; and later a curricula focus and teacher professional development on deep content rather than casual coverage of categories of knowledge. Technology, including computers, content knowledge in a wider range of disciplines than FCL, collaboration with colleagues, exible student scheduling, context that value in-depth exploration of fewer topics rather than facts. Focus on sustained thinking about authentic problems using in-depth inquiry in science, social studies and mathematics, often utilizing multi-media materials. Elementary and Middle Elementary The approach emphasizes building a caring community of learners, the social and ethical as well as intellectual dimensions of learning. Literature-based reading and language arts; Collaborative classroom learning; Developmental classroom management using problem-solving; Parent involvement; Relationship-building within and between classrooms: and a school wide program that promotes inclusion and the values of a caring community. New teacher learning is required in areas of childrens social-psychological development, constructivist teaching, and classroom management based in developmental discipline. Literacy materials. School and district support for a social and ethical emphasis. Schools for Thought (SFT) Child Development Project (CDP)

Target population Program Philosophy

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

Program Activities

Resource and context demands

Deep disciplinary content knowledge, developmentally appropriate reading materials, physical space, contact with outside experts, technology, collegial relations

303

304

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

data collection including the elementary schools during the last year of the study. The reform sample was strategically selected to afford an opportunity to study reform sites with varied context dimensions, namely the level and type of district/state involvement; range of principal and teacher experience and participation; nature and kind of teacher communities involved; school population (from large urban to suburban, from predominantly African-American to Latino to mixed to majority white populations). This variation provided a rich base to examine the range and depth of educational issues implicated when diverse reform ideas, their change strategies, and the reforming process interact with varied context conditions. The research methodology for this study involved mixed methods, incorporating qualitative eldwork with surveys, and using a nested sampling approach. More in-depth casework (site visits and interviews) was conducted in the core case sites. To capture the importance of multiple embedded contexts and the multiplicity of perspectives (especially teacher communities) located within each context that inuence educational change, data sources to elicit the range of perspectives framed data collection efforts, with primary attention to the teachers perspectives. The main data sources were annual interviews of reform founders, reform staff, district personnel, principals, and teachers. A range of perspectives was deliberately sought, from devoted advocates to willing participants to skeptics and non-participants wherever possible. Classroom visits also occurred during each year of the study. Other data sources supplementing the above work were surveys, teacher focus groups, document collection (from schools/districts and site visits, and from the reform program) and data sharing between the collaborating partners (additional interviews, meeting notes, summer institutes, in-service binders, curricula, teacher journals and products, videotapes, publications, assessments, other documentation, and research results).

S USTAINING T HEORY-BASED C HANGE : G OING D EEPER Sustaining theory-based change requires more than maintaining the status quo or merely continuing the level of implementation achieved when special project resources and attention end. Sustaining theory-based change means deepening changes in practice and understanding in ways that keep practice vital, responsive to changes in students, subject area content and classroom contexts.6 Ironically, reformers and reform advocates, policymakers and funders often pay little attention to the problem

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

305

TABLE II Sustaining theory based change requires Sufcient resources Knowledge of rst principles Supportive community of practice Supportive principal Compatible district context

and requirements of sustaining a reform, when they move their attention to new implementation sites or end active involvement with the project. We nd that teachers ability and willingness to continue a reform, to reect on it, and to keep it a vital part of their classroom practices turns on a number of factors and conditions:7 Resources The requirement easiest to see and understand is resources. Theory-based reforms are resource demanding since the basic stuff of the reform is generally not found in most schools or classrooms both physical and human resources. FCL, for example, goes beyond the typical elementary school reader to build from varied, rich reading materials to support students research. It also relies on additional human resources in the classroom. Reciprocal Teaching [RT] for FCL uses a classroom aide to track down research materials for the class, keep them current and accessible, and work with students. Yet these resources, available as part of the hot house period of invention, are in scarce supply in regular school budgets. FCL teachers doubt they can sustain their new practices without this additional classroom assistance: I can tell you now, if I have no support people in here next year, I wont be doing FCL. It cant be done. CDP teachers enjoyed support from the DSC in the form of research materials, suggestions for classroom activities, and a supply of new materials for instruction. In all of these reform initiatives, teachers are of a voice in saying that in order to sustain their new practices they would need continued access to these materials. Making provision for the resources necessary to sustain a reform effort is a bottom line reformers need to negotiate at the outset with the implementing site or with funders. The challenge to reformers is to use the process of invention of moving theory into practice and practice into theory as occasion to understand the resources required to sustain a

306

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

reform in real school and in terms of real budgets, rather than in the boutique setting of a research and development effort. Reformers Learning as Reforms Move into Classrooms Most change models do not consider the passage from the university laboratory to the classroom as an essential aspect of the process, and dene getting started in terms of adoption or adaptation by the implementer.8 Unlike reforms that can be added to existing practice, or adapted to t specics, theory-based change requires construction once it leaves the sheltered environment of a university laboratory. We call the rst task in a theory-based change process invention since it requires moving theory into practice, and elaborating theory in ways that both resonate with practice and reect essential elements of its theoretical base. Moving from vitro to vivo requires the collaboration of reformers and practitioners and assumes that the reform itself is unnished until that co-construction takes place. It is not news that teachers have much learning to do as they encounter and work with unfamiliar ideas and practices. But invention also requires much practical and theoretical learning on the part of reformers. This dimension of moving ideas into practice is neglected altogether in the planned change literature.9 Reformers need to learn about teachers workplace contexts, the rhythm of their day, and the norms that inform practice and routines. They need to learn about the contexts outside of inventing sites that compete for teachers time and attention, or that conict with reform principles accountability systems, other reform initiatives, community pressures, the broader policy context. Working with teachers in real-life classroom settings affords reformers opportunity to learn more about the reform itself and build a repertoire of contextsensitive theory-into-practice that can inform implementation and future invention. Knowledge of First Principles Implementation takes on a particular meaning in the instance of theorybased change. Many analysts cast the primary focus of implementation in terms of putting particular activity structures, materials, or routines in place, and often that is all that is required. Theory-based change focuses attention instead on implementers understanding the principles that underlie them.10 Teachers need to know, understand and enact the rst principles that constitute the grammar for the reform not only the activities or practices associated with it. Implementation is both assimilation and construction, and must be anchored in general reform principles and

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

307

concrete teaching contexts. The on-going interaction of reform, learning and context means that implementation is, itself, a process requiring ongoing invention. Lacking knowledge of rst principles, teachers risk constructing lethal mutations in their classrooms, as they modify practice, or extend it and unintentionally violate rudiments of the reforms theoretical base. Some teachers associated with Fostering a Community of Learners, for example, did not understand that simply having students read aloud to one another was not Reciprocal Teaching. Without understanding the theory upon which their new practice is based, teachers lack the capacity for selfcritique or for providing reective feedback for colleagues, so practice likely will stagnate. The problem for implementation is not only one of teachers learning how to do it, but of teachers learning the theoretical percepts upon which participant structures and activity structures are based. Absent knowledge about why they are doing what theyre doing, implementation will be supercial only, and teachers will lack the understanding they will need to deepen their current practice or to sustain new practices in the face of changing contexts. Teachers need knowledge of a reforms rst principles if they are to sustain their reform-associated practices after special project status ends. More important than activities, materials and strategies, without principled knowledge, teachers lack the capacity to respond to competing pressures or challenges in their environment. Susan Goldman, a co-inventor of Vanderbilts SFT program, relates the difcult lessons Vanderbilt reformers learned: The district changed the curriculum objectives from relatively broad content specication with lots of exibility in sequence to specic mandates on what was to be taught and when. Many SFT teachers felt that if they couldnt use the units they couldnt do the program. Unless the teachers have an armor to take with them [rst principles] then the program falls apart as soon as one piece of it is no longer relevant. SFT professional development and support had focused almost exclusively on procedures for doing SFT: teachers skills at using computers in their classrooms, and how to conduct reciprocal teaching or jigsaw strategies, but provided almost no explicit exposure to the rst principles of the reform. Teachers, as a result, did not understand why the strategies associated with SFT were important, and so could not adapt their practice to changed circumstances. John Bransford, a co-inventor of Vanderbilts SFT program, reects: We didnt give them a user-friendly theory of learning that lets them think critically about their practice and be generative.

308

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

Based on these experiences, SFT researchers fundamentally revised teacher professional development activities to start with the theory underlying SFT, expressed in a user-friendly form. Bransford summarized: Weve been working a lot on trying to help teachers to think about issues of learning in ways that let them see that . . . a good theory will really generate good practice. We didnt introduce a technology tool at all this past six months when we were doing the six after school sessions. They just focused on content in their domain, the learner and processes . . . . I think that has been successful. Currently, professional development staff provide opportunities for teachers to focus on student understanding and examine their assumptions about content domain learning and how students develop it.11 This new approach met with opposition from project teachers who said they wanted concretes they could use right away in their classrooms. SFT researchers told us:

. . . when we switched direction this year from the implementation mode of us telling them what to do, they werent very happy about it at all . . . [They] took me aside and said, Were not going to do this again. Well stick with you right now . . . We dont want to pull out in the middle, but this is a totally different feel. Youre asking for a lot more now. Its a switch from our project, to having them lead what they want to work on [with us as resources]. It took months to get on really comfortable ground. But recently one of them said, I know what it was now . . . You guys were asking us to think. We didnt want to do that. Its tough to rethink what youve been doing.

One way to alleviate anxiety associated with engaging teachers in learning the theory underlying the effort was to encourage teachers to begin with changing just one area of their teaching. An SFT staff developer described the important changes in the Learning Technology Centers work with teachers: We now tell teachers that we want them to take some pieces and work on them slowly. When they get that piece done, well move on to another piece . . . And in about two or three years growth theyll have all the pieces [of the theory]. The Child Development Project started out to expose teachers to core principles from the beginning. Marilyn Watson, a chief CDP architect and designer of teacher training, said: We had a very strong belief that teachers needed material to scaffold their performance in the classroom to help them understand the theoretical constructs that we were talking about in the workshops . . . . CDP also constructed their workshops and training sessions in ways that required teachers to think through project essentials and not just be told them. CDP trainers describe how they countered teachers questions for clarication and direction with What do you think? That reply, a trainer told us, was really to remind teachers that theyre not to regard us

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

309

as the expert, but that the goal is [to get teachers to think deeply about the project.] . . . So thats the art form of staff development . . . probing them to think more deeply. CDPs investment in teachers learning why as well as how to implement the project has paid off in teachers ability to not only sustain the work they had done under the project umbrella, but also to extend it to new areas of the curriculum. For example, teachers in a Louisville school pointed to science materials they had used the CDP way, to engage students in discussions of ethics and moral decisions. Once you learn the underlying ideas, they told us, you can CDP any piece of curriculum. A Supportive Community of Practice The experience of these three theory-based reform efforts suggests that while the focused involvement of one or two teachers may be the best strategy during the period of invention, when reformers are working to instantiate their theories in practice and to understand how particular contexts affect their design, implementation should aim to embrace the whole school, and foster teacher learning and buy-in on a broader scale. Sustaining practice also requires a community of practice to provide support, deect challenges from the broader environment, and furnish the feedback and encouragement essential to going deeper.12 The classroom-based projects we examined typically lacked such a school-level professional community understanding of the reform, and teachers found it difcult to continue their project work as a consequence. One of the founding FCL teachers, for instance, talks about the difference in her ability to work with the reform in different school contexts: At [my old school] I was by myself in my own classroom . . . . I needed a community . . . Community is the core of FCL. The principal of a school stresses that introducing FCL schoolwide, rather than in one or two teachers classrooms would have to be the whole focus of the school, not just one classroom . . . . Thats how to make it real, not just an experiment. CDP came to the same conclusion and began using a whole-school approach, focused explicitly on building a community of practice to sustain the reform over time.13 CDP now takes teacher community as the primary vehicle of learning and a major goal of the reform itself. For example, one cornerstone of CDP in-service was a purposeful mix of teachers who normally do not work together, such as primary and upper grade teachers, so that teachers were very familiar with what everyone else in the school is doing. A teacher commented; Were all moving so well together in the same direction, we all know whats going on. Visiting CDP schools three to ve years after the formal involvement with the project ended, we saw

310

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

that these communities of practice continued to function both to sustain project norms and values, and to induct teachers new to the school to the CDP way of doing things. SFTs experience also underscores the important role of community as a support for teachers continued growth and development. A Vanderbiltbased researcher commented, Ive been involved in three or four schools with research, and one of the schools involved only seven classrooms, and the other school I worked in involved the whole school and it was tremendously different because, when somebodys doing something special, you start cracking the unity of the staff. They changed their philosophy because a classroom-by-classroom focus was often divisive for participating teachers. One teacher told us: There were some negative things our rst year because we were different, and we had a special frame, and we got to leave school, and we had help, and all those kinds of things . . . We got a lot of extras, they didnt understand how much work we were doing. In a staff meeting one teacher not working on SFT commented, What are we? Schools for Non-Thought? The SFT professional development model began following a similar path of focusing on the teacher as reform agent in 1999.14 The recent introduction of a site facilitator for each SFT site has helped with building a community of practice. The site facilitators work with teachers, principals, and librarians to think how to better work as a team and how to incorporate SFT into the school so that it is sustainable. In this current form of SFT support, any teacher can come to these meetings, not just the teacher receiving SFT training. At some schools this is most of the staff. For example, a school with only one SFT teacher has 11 staff members coming to the meetings. The school has also provided technology for other teachers, which has helped to eliminate the haves/have nots problem at the site. Teacher leadership was another important element of school-based professional community that builds upon the rst principles to reform practices. In one SFT school, for example, a teacher was not only a model teacher in his classroom, but other teachers at his school looked to him for help as they undertook the reform effort. His leadership is widely regarded as the key to the spread of the reform in his school.15 In their latest work, the SFT professional development model actively works toward the development of teacher leaders who are seen as collaborating equals who facilitate the learning of their peers rather than as experts on the theory. Beginning in 1999, SFT has focused intentionally on encouraging teachers to develop their own understanding of how to reframe what they do with students so that they see SFT principles as the foundation for an

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

311

inquiry process in their own classrooms.16 CDP has similarly identied the importance of teachers developing their own understanding of reform. In CDP schools, for example, involvement of teachers as model teachers and in-service presenters strengthened reform participation, as long as the lead teachers did not retain their separate status as leaders, but quickly engaged their colleagues in helping to construct and sustain the reform effort. A Knowledgeable, Supportive Principal Sustaining theory-based change after special project status ends also requires a supportive principal, one who not only understands the values and perspective underlying the project, but also actively endorses its core principles from the beginning of the project. Principals who are not conversant and appreciative of these norms of practice might create a school environment that either competes or conicts with practices associated with a theory-based reform. For example, a principal at one of SFTs agship schools ostensibly supported SFT because of his strong support for technology. Yet, his ideas about technology differed in critical ways, and SFT teachers felt marginalized given their principals somewhat different technology agenda. Schools for Thought founders now believe that they neglected an essential element when they initially by-passed principals in project professional development and implementation activities. They relied on principals for their administrative support (e.g., exibility in scheduling), but not for their instructional leadership. Goldman pointed out that the revised project strategies now involve the principal as instructional leader of a site based community . . . . [In our original effort], principals had to be on board with it but they didnt have to do anything but be passively supportive. But [we have learned that] passive support will not sustain SFT practice. As a result, all new teachers applying to receive SFT training must have the explicit support of their principal to receive the training. The principal also is expected to participate in the monthly site meetings with teachers, the librarian, and the SFT site coordinator as a way to structure regular principal participation in the reform. Initial results of this emphasis show correlation between individual teacher change and quality of the school community.17 At successful CDP schools, principals served both as instructional and cultural leader. A CDP trainer echoes SFTs lessons about what active principal support must comprise:

Number one, they have to deeply understand it. So if they do that, then they are willing to put themselves on the line to support the project . . . Setting a tone that is not only positive, but non-threatening to people. And also a tone of high-expectation and expectation that

312

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

well all keep trying even though we might not all agree with some pieces. Its a combination of making sure the day-to-day is running smoothly in a school so that change can be attempted . . . And then theres that piece of going beyond and kind of being the beacon and the inspiration to keep people looking towards something new.

CDP principals were learners themselves, and took an active role in building learning communities to deepen practice. They participated in teachers workshops or other project learning opportunities. One CDP teacher said, for example, The [principal was] always there during all the training and just supportive . . . you had to have the leadership to make this project work . . . we were all equal on that team. I think that experience helped [our principal] listen to us. Compatible District Context Compatibility in this instance refers to norms of practice. Even the most dedicated teachers and principals will have a hard time sustaining reform practices and philosophy if their district context is hostile or pushing in incompatible directions. Prior to 1997, the superintendent of Nashville strongly supported SFT. One teacher spoke of the legitimacy that the former superintendent brought to SFT: [The superintendent] would actually come to visit our school to see what we were doing. And that made you feel like the power structure is behind this, this is a good way to go. It made a difference. Not only did the [superintendent] come, but he brought the whole Chamber of Commerce. They came in on buses to look at Schools for Thought. Efforts to sustain SFT were undermined in Nashville when the sudden departure of a supportive superintendent in January, 1997 brought several changes, including the highly specied and mandated Core Knowledge curriculum. Teachers involvement in SFT was compromised by this shift in district context. As one SFT staff put it: If you have a thumb in the back saying, If you dont do Core, youre going to be red, what are you going to do? Schools for Thought? Or Core? Youre going to do Core. While the previous superintendent was, in the words of one project staff member extremely supportive of technology in the classrooms, very supportive of moving away from rote learning to hands-on, constructivist, critical thinking emphasis, they failed to realize the degree to which the other members of the central ofce staff didnt really buy into the superintendents vision. When the superintendent resigned, district support vanished and SFT teachers found themselves adrift in a district setting embarked on a contrasting reform agenda.

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

313

At the time of the shift in district leadership in 1997, Goldman reected on what she and her colleagues at Vanderbilt learned from their experience with their projects context:

One big lesson is that you have to build for the instability, all the changes, in the system at all levels. There is no level at which the system is not changing not in terms of kids in classes, not in terms of teachers, not in terms of the district policy, and so on. You have to think about whether what you are doing is going to be robust enough to survive when everything around it is unstable and changing. I was not thinking that way several years ago.

CDP was particular among these three projects in that the Developmental Studies Center planned for instability at all levels of the implementing system. The DSC worked to embed CDP principles and support throughout the district, rather than just at the top. CDP planned for changes at the teacher level by ensuring that teachers fully understood the projects rst principles, and so could adapt and grow as new students, new curricula and new requirements entered their classrooms. It planned for instability at the school or organizational level by focusing both on the development of a teacher community committed to CDP, and by engaging principals from the beginning in project sessions and professional development. Principals were the focus of learning and invention no less than were teachers. It involved district personnel in professional development activities and visited regularly to answer questions and provide materials. The result, as one CDP teacher put it, CDP is in the walls of this school. Even if our [current and extremely supportive] principal left, this faculty would not have another principal who didnt support CDP. Thus, teachers new to the community were quickly socialized to its norms and values. Looking back on FCL efforts, Ann Brown commented on the limits of a teacher-centric effort that ignores other critical aspects of the context, If youre [a teacher] doing something by yourself, and no one knows, its self-defeating. FCLs current efforts build on this experience to include an entire school in FCL, rather than targeting only a few classrooms, and by creating an agreement of support with the superintendent and key staff from the start of the project and by having a community advocate who had a strong relationship with the district to serve as a mediator. By all accounts, this attention to FCLs school and district context led to a depth of implementation and integration into school and district priorities that the project did not achieve in earlier sites.

314

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

TABLE III Going to scale requires Teachers invest their professional repertoire in the reform principles. School system provides ongoing learning opportunities, allocates resources and materials, assumes responsibility to lead ongoing reform implementation, and exercises authority to manage the variable enactment of reform practice. Reformer can no longer be sole proprietor.

G OING B ROADER WITH T HEORY-BASED C HANGE Most strategies and policy conversations directed at scaling up the fruits of education research and development (or pumping in the Texans terms) frame the problem of scale primarily in terms of spreading or replicating specic practices.18 This view of the problem is, as Ann Brown puts it, a chimera, when it focuses attention on material, surface or procedural aspects of a reform to the neglect of the norms and philosophies or the rst principles that are essential to situating and sustaining it. Ann Brown and Joe Campione advised: It is the rst principles, not the surface procedures, that we want to disseminate. And it is these that we wish to share with teachers, so that they are free to design or modify any surface activity in ways that are consistent with the principles.19

W HAT D OES G OING TO S CALE M EAN ? Scale, in the instance of theory-based change, is affected by the degree of consistency between the value basis and the beliefs underlying a reform, and those of its organizational and institutional setting. A reform can be said to be an accepted practice when it is no longer seen as an interruption or exception to organizational life. Going to scale has as much, if not more, to do with the normative structures of the organizational setting as it does with the procedural structures. Going to scale involves all of the issues and requirements associated with sustaining change and more. Going to scale requires support not only for sustaining existing practices, but for broadening the reach of the reform at multiple levels of the system the individual teachers classroom, the school and the district. Going to scale involves managing

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

315

and supporting teachers efforts to sustain and deepen their practices while also engaging teachers new to the reform. The initial cohort of teachers engaged in a theory-based change effort enjoys important resources of money, time, equipment and technical assistance. Subsequent groups of teachers must do much if not all of the same work of invention, learning core principles, and embedding them in their practice, but with much fewer resources. Going broader while going deeper thus engages all elements of the change process simultaneously inventing, implementing and sustaining reform. One way to think about scale in the instance of theory-based reforms is in terms of the consistency and coherence of the multiple messages sent to teachers. District curricula, reform initiatives, accountability schemes, teacher evaluation and promotion strategies all communicate values and priorities to teachers. To be sure, the difculty of fostering some measure of coherence with the norms and values operating in a school or classroom context is heightened by the fact that most district policy environments resemble a pharmacy, with multiple and often incompatible prescriptions at work simultaneously. Yet, moving theory-based reform to scale requires deep and exible understanding of context, otherwise both reformers and implementers are handicapped.20 We also see that going to scale means different things at different levels of the system. Going to scale at individual and school levels essentially signals issues of sustaining and extending teachers reform practices while sustaining what already exists. At the level of an individual teacher, bringing a reform such as FCL to scale may mean extending reform practice broadly, beyond existing units of instruction spreading reform pedagogy across subject areas, applying reform knowledge to selection of new materials, using reform principles to reconstruct approaches to student assessment, and so on. When FCL moves from occupying a discrete portion of teaching activity to characterizing the whole of a professional practice, reform has been brought to scale at the individual level. Similarly, reform on the scale of a school organization may mean that reform practices occur not only in one or two exceptional classrooms, but also in classrooms across the school, and reform principles inform organization-level decisions and routines. This notion of scale means not only breadth of procedural change across the unit of interest (classroom, school, district); it also means that the changed practices signify, emerge from, and reinforce layers of knowledge, norms, and activities that constitute a whole professional practice or the workings of a whole organization. For a teachers practice to be an FCL practice or for a school to be a CDP school means that reform is also

316

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

occurring on the dimension of depth. It is for this reason that we inextricably link scale with the capacity to sustain reform practice: the breadth and depth of its effect on practice (at whatever unit of change) means it becomes, in effect, rooted there. As internalized as belief, practice, norm, and policy, the reform principles become self-generative. They become the normative grammar for future action. Given these dimensions of change, scale presents a problem that is exponentially more complex than the problems of invention and implementation. It requires that the reform undergo transition from being an external entity to an internal one at individual, organizational and institutional levels. The embedded contexts in which teachers and schools sit thus become the crucial actors for reform. Going broader at the district level can mean a number of different things. It might mean a corridor of practice where students move through classrooms associated with the reform. Both FCL and SFT imagined scaling up in these terms. It might mean a cluster of schools engaged in the reform. Or, it might mean embedding the core principles and practices in district policies and routines. While corridors have proven difcult to maintain, our experience suggests that this latter meaning of going to scale as embedding core principles is both the most demanding, and ultimately the most essential for practices to be sustained at any level, classroom, school, corridor, cluster or any other conguration. C HALLENGES OF G OING TO S CALE Reformers face a number of issues in addressing the problem of scale in the instance of theory-based projects. First, individual change on a scale larger than a segmented portion of practice implicates not only teachers ability to learn to do the reform; it demands that teachers commit to investing their professional repertoire, perhaps even their identity, in the reform principles and practices. The extent to which this investment represents fundamental change or extension of existing beliefs and practices obviously depends on the context of teachers existing work and workplace which in turn has implications for investment of reform resources and design of learning opportunities and support. Working to scale at an organizational or institutional level draws the reform onto a much larger stage, where explicit policies are operating at multiple levels of the system (school, district, state, federal and national), and where embedded cultural and organizational traditions of the schools exert force implicitly. For reforms to be realized in practice on an organizational or institutional scale, the internal (school system-based) policy and

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

317

cultural systems must have the capacity and will to commit to the principles and practices of the reform, either by changing or by buffering them from inconsistent practices or norms. Going to scale requires compatibility between the core values of the reform and both the procedural and normative structures that operate in the broad context. Second, sustaining reform principles and practices as professional practice or organizational routine means that the school system not the reform project must provide teacher learning opportunities, allocate resources and materials, assume responsibility to lead ongoing reform implementation, and exercise authority to manage the variable enactment of reform practice. Thus, one problem of scale is to build reform-centered knowledge, material, and leadership capacity within the many layers of the school system so that informed judgments can be made about the extent to which school and district practices adhere to core principles, even though material and practices may have evolved over time. Third, the problem of scale alters the reform founders relationship to the reform itself. Internalizing reform involves reconceptualization of proprietorship, moving from reformer as sole proprietor (or limited partnerships with practitioner co-creators) to reformer as one of many sources of wisdom and authority about the reform. S TEPS R EFORMERS C AN TAKE TO S UPPORT S CALE These reforms had very different experiences with scaling up, or going broader with the reform effort. FCL, which was never fully focused on questions of dissemination and scale, in fact lost rather than expanded initial sites as teachers isolated in their schools became discouraged or felt they had insufcient resources to continue. SFT suffered a blow to their plans to expand project activities when the district suddenly changed instructional direction. Since the shift in district context, SFT has focused training individual teachers as the unit of change and has fostered support for these teachers through discussions at their site and in teacher learning communities. CDP, drawing on over 15 years experience, achieved some important measure of success in broadening project activities in demonstration schools and districts. We derive a number of lessons from this collective experience about things reformers can do both early on and during implementation to increase theory-based projects chances of going broader, as well as going deeper strategic site selection, taking a proactive stance toward context, and developing strategies for transferring authority and ownership of the project to teachers, schools and districts.

318

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

TABLE IV Steps reformers can take to support scale Careful attention to site selection. Proactive stance toward district contexts. Transfer of authority planned from the start. Strong community of practice.

Site Selection All of the reform founders point to site selection as critical to all aspects of project vitality, effect, and stability. Site selection engages questions of scale and starting points start with a handful of interested teachers and schools? Start with the system? Starting small can aid invention by having time to clearly teach rst principles, but can frustrate implementation and stall efforts to go broader at individual, school or district levels if broader capacity and knowledge sharing is not developed. John Bransford says that one of the most important lessons they learned through their SFT efforts was not to come in as this specialized program thats only helpful to a few schools . . . . Our goal has to be to help the system as a whole. Developmental Studies Center was perhaps most strategic in choosing their demonstration sites with an explicit assessment of the districts and schools capacity to sustain and broaden the reform once their involvement ended. They chose districts that had commitment to professional development and some sort of reputation of good relationships with teachers. DSC staff also advised that another thing to look for is whether the district is willing to put on the table someone whos actually capable of leading. Do the people theyre giving you as their district people, have the voice of the superintendent, or do they have access to the top levels in the district. Then we did school visits and sized up the principal and looked at the staff. A Proactive Stance toward District Contexts Reformers associated with each of these efforts acknowledge the importance of the district as a mediator of their projects chances for expansion, or even survival of a theory-based reform. CDP staff, for example, found that the one district where it didnt work out was a district where the coordinator had a lot of other responsibilities and we had to work around her, rather than work with her. A district that worked really well was one in which a person in the district basically lived the project. We didnt have to

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

319

say, You need to be thinking about this and you need to be thinking about that. She was calling us saying, You need to be thinking about this and you need to be thinking about that. Issues of both implementation and scale require development of leadership and commitment to rst principles of the reform at all levels of the system a painful SFT lesson. When district leadership changed hands in 1997, Vanderbilts SFT staff feared that the conicting new district paradigm would prove to be a major impediment to including new teachers in the project: The new district agenda [Core Knowledge] has devastated any plans for scale. Individually, [committed SFT] teachers think they can balance Core and SFT as long as they can be exible with the Core mandates. [But] most teachers cant imagine taking on Schools for Thought if they havent before, and those who are doing it, have put it on the back burner for a while. Without district support, Vanderbilt staff were concerned that only pockets of SFT practice would continue in classrooms where teachers have really bought into the program and made it central to their practice. These examples suggest the importance of linking reform concepts with other issues in the district, and taking a proactive stance toward the context in which the project must be supported and valued. For example, CDP staff worked with Louisville educators to show them how CDP could support the efforts required under the Kentucky Education Reform Act, thereby connecting CDP to the districts dominant regulatory framework. SFT subsequently took an active role in enabling Nashville teachers to work with SFT rst principles while also responding to Core Knowledge requirements. Reformers also confront the need to be political. John Bransford reects on the obligation he feels to enter the broader district conversation: I hate doing a lot of these things [such as talking with the school board, giving presentations at community meetings] . . . . I think [academics] strategy is to rely as much on data, and bring science into a political context and to educate the community about what the real issues are over time. Being political also means, Bransford says, paying much more attention to the global contexts of your intervention and that includes really knowing your school board, your superintendent, your principals. Transfer of authority Reform initiatives often fall at when reformers withdraw their support and attention from invention and implementation sites. Many reformers and funders see their role dened by a grants implementation schedule. The experiences of these reform efforts make clear that how a reform effort

320

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

exits a site is critical to the projects longer-term existence at any level of the system. The Child Development Project, drawing upon some of their own hard-earned experience, was planful about when and how they transferred authority for the project to teachers, schools and districts. They developed multiple occasions to enable schools and district to take ownership of reform and the principles that underlie it for teachers to develop the condence to make their own decisions related to project activities. CDP staff saw this process essentially as a teaching task, and in the last year of involvement with schools and districts, they set about to make this transition:

We presented information to the site team people and said, these are some options you might want to use. But the site teams have already become independent enough to say, we will use that and no were not going to use that . . . So theres already been some independence thats grown [from] Help! What do we do? [to] We know what we need, thanks very much for the info, but this is what were going to do.

Part of the tension of letting go is acknowledging that ownership of the principles becomes transferred as well. A CDP staffer comments, [Looking at] the choices they make, we would have made other choices. Its like parenting. CDPs experience cautions reformers to pay as much attention to strategy at the end of a special project as they do to buy-in and learning at the beginning. Vanderbilts transition of authority of SFT to the district has required district staff and Vanderbilt personnel to work together, and the two groups have learned that districts make decisions quite differently. These differences have resulted in what could be considered a clash of cultures, with district personnel emphasizing clear rules, consistent procedures and efciency and Vanderbilt staff focusing on continual reassessment and knowledge generation.

C ONCLUSION : D OING E VERYTHING AT ONCE Theory-based reform does not move through discrete stages in which problems are solved as implementers co-invent, carry out and then attempt to go deeper and broader with reform practices. The issues posed by these tasks call for different resources, and dene different roles for founders and educators, but they also co-occur in fundamental ways. We nd that sustaining and expanding reform practices inevitably revisit the tasks of invention and implementation, as teachers veteran to the project must reinvent the reform to keep it relevant and vital in their classrooms, and as

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

321

teachers new to the project struggle to make it part of their practice. We see that going deeper and going broader with a theory-based reform depends in fundamental ways on what happened as the initiative moved from laboratory to classroom, and into implementation sites. Can reformers attend to everything at once think about inventing on a small scale, while also anticipating the challenges of sustaining, deepening and expanding theorybased reform at the school and system levels? Do the individuals who can imagine and invent theory-based reforms necessarily possess the political and strategic skills important to sustaining and broadening them? Few funders, policymakers or reformers have tackled these complex and difcult questions. But they may be among the most important questions of all if education research and development efforts are to provide a signicant return on the resources invested in them.

N OTES

1 Stokes et al., 1997; The Mellon and Russell Sage Foundations supported this research. 2 Brown & Campione, 1996. 3 Research on all three had been conducted under the auspices of the CSEP (Cognitive

Studies of Educational Practice, James S. McDonnell Foundation) program and shared compatible goals and visions for middle school instruction. 4 Lamon et al., 1996. 5 Lewis, Watson & Schaps, 1997. 6 Hargreaves & Fullan, 1998. 7 For other discussions of factors affecting implementation and sustainability of theorybased reforms, see Bol et al., 1998. 8 See, e.g., Fullan, 2001. 9 With the notable exception of Schwab, 1970. 10 Important exception to this claim is Cohen & Barnes, 1993. 11 The model, Content-based Collaborative Inquiry, emphasizes learning communities and works toward supporting the development of these (Zech et al., 2000). 12 See McLaughlin & Talbert, 1993, 2001 for a discussion of the connections between professional communities and teachers willingness and ability to rethink their practice. 13 Lewis, Watsonm & Schaps, 1997. 14 Zech et al., 2000; see also Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1999. 15 Bray, 1998. 16 Zech et al., op. cit. 17 Goldman et al., 1999. 18 See, for example, Bodilly, 1998; Elmore, 1996; Stringeld et al., 1998. 19 Brown & Campione, 1996, p. 265. 20 The discussion of the quasi-practical in Schwab, 1970 also emphasizes the importance of context mediating the relationship between theory and practice.

322

MILBREY W. MCLAUGHLIN AND DANA MITRA

R EFERENCES

Bodilly, S.J. (1998). Lessons from New American Schools Scale Up Phase. Santa Monica, CA: RAND. Bol, L., Nunnery, J.A., Lowther, D.L., Dietrich, A.P., Pace, J.B., Anderson, R.S., BassoppoMoyo, T. & Phillipsen, L.C. (1998). Inside-in and outside-in support for restructuring: The effects of internal and external support on change in the New American Schools. Education and Urban Society 30(3), 358384. Bray, M.H. (1998). Leading in Learning: An Analysis of Teachers Interactions with Their Colleagues as They Implement a Constructivist Approach to Learning. Doctoral dissertation, School of Education. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University. Brown, A.L. & Campione, J.C. (1996). Psychological theory and the design of innovative learning environments: On procedures, principles and systems. In L. Schauble and R. Glaser (eds), Innovations in Learning: New Environments for Education (pp. 289325). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Cochran-Smith, M. & Lytle, S.L. (1999). Relationships of knowledge and practice: Teacher learning in communities. In A. Iran-Nejad & D.P. Pearson (eds), Review of Research in Education (pp. 249305). San Francisco: American Educational Research Association. Cohen, D.K. & Barnes, C. (1993). Pedagogy and policy. In M. McLaughlin and I. Oberman (eds), Teacher Learning: New Policies, New Practices. New York: Teachers College Press. Elmore, R.F. (1996). Getting to scale with successful educational practices. In S. Fuhrman & J. ODay (eds), Rewards and Reform: Creating Educational Incentives That Work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Fullan, M. (2001). The New Meaning of Educational Change: Third Edition. New York: Teachers College Press. Goldman, S.R., Bray, M.H., Cynthia, L. Gause-Vega, C.L., Zech, L.K. & the Schools for Thought Professional Development Group (1999). A Learning Communities Model of Professional Development. Presented at the Invited Symposium 8th European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction, Gteborg, Sweden, August. Hargreaves, A. & Fullan, M. (1998). Whats Worth Fighting For Out There. New York: Teachers College Press. Lamon, M., Secules, T., Petrosine, A.J., Hackett, R., Bransford, J. & Goldman, S. (1996). Schools for Thought: Overview of the international project and lessons learned form one of the sites. In L. Schauble & R. Glaser (eds), Contributions of Instructional Innovation to Understanding Learning. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Lewis, C.C., Watson, M. & Schaps. E. (1997). Conditions for School Change: Perspectives from the Child Development Project. Oakland, CA: Developmental Studies Center. McLaughlin, M.W. & Talbert, J.E. (1993). Contexts that Matter for Teaching and Learning. Stanford University: Center for Research on the Context of Teaching. McLaughlin, M.W. & Talbert, J.E. (2001). Communities of Practice and the Work of High School Teaching. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Schwab, J.J. (1970). The Practical: A Language for Curriculum. Washington: National Education Association Center for the Study of Instruction. Stokes, L.M., Sato, N.E., McLaughlin, M.W. & Talbert, J.E. (1997). Theory-based Reform and Problems of Change: Contexts that Matter for Teachers Learning and Community. Stanford University: Center for Research on the Context of Teaching.

THEORY-BASED CHANGE AND CHANGE-BASED THEORY

323

Stringeld, S., Datnow, A., Ross, S. & Snively, F. (1998). Scaling up school restructuring in multicultural, multilingual contexts: Early observations from Sunland county. Education and Urban Society 30(3), 326357. Zech. L., Gause-Vega, C., Bray, M.H., Secules, T. & Goldman, S.R. (2000). Contentbased collaborative inquiry: Professional development for school reform. Educational Psychologist 35(3), 207218.

AUTHOR S B IO

Milbrey McLaughlin is the David Jacks Professor of Education and Public Policy at Stanford University. Professor McLaughlin is Co-Director of the Center for Research on the Context of Teaching, an education research center supported by both federal and foundation funding, and Executive Director of the John Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities, a partnership between Stanford University and Bay Area communities to build new practices, knowledge and capacity for youth development and learning. She is the author or co-author of a number of books, articles, and chapters on education policy issues, including her latest work: Communities of Practice and the Work of High School Teaching (with Joan Talbert, University of Chicago Press 2001). Dana Mitra is a doctoral student in the Administration and Policy Analysis program at Stanford Universitys School of Education. She received her A.B. from Brown University (Educational Studies and Public Policy) and her M.A. from Stanford University (Sociology). Mitra also is a research assistant at the Center for Research on the Context of Teaching, an education research center supported by both federal and foundation funding.

MILBREY M C LAUGHLIN

Stanford University CERAS Building Room 402 520 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3084 USA E-mail: milbrey@stanford.edu

DANA MITRA

School of Education Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-3084 USA E-mail: dmitra@stanford.edu

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- FFA UNESCO Framework For Action - EducationDocumento83 pagineFFA UNESCO Framework For Action - EducationMathilde de la PaixNessuna valutazione finora

- Weber Et Al. What Customers Really NeedDocumento15 pagineWeber Et Al. What Customers Really NeedMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Eduinnovationmahathir PDFDocumento1 paginaEduinnovationmahathir PDFMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- PUBLIC REPL World Bank Report 07 Education FA Full WEB PDFDocumento52 paginePUBLIC REPL World Bank Report 07 Education FA Full WEB PDFMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- ISO 9000 Awareness Presentation 8-27-15Documento19 pagineISO 9000 Awareness Presentation 8-27-15mahinda100% (1)

- Theory CntigencyDocumento28 pagineTheory CntigencyMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary PHD Thesis Inge de KortDocumento3 pagineSummary PHD Thesis Inge de KortMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Suerf ViDocumento44 pagineSuerf ViMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- OutDocumento114 pagineOutAhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Thematic Analysis Exercise - A Study On Violence and Aggression (Smith and Osborn 2003)Documento1 paginaThematic Analysis Exercise - A Study On Violence and Aggression (Smith and Osborn 2003)Mahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- 01 Irma OKDocumento7 pagine01 Irma OKMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- TQM Seminar Paper 5Documento30 pagineTQM Seminar Paper 5Mahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- 99 Racz Irma PaperDocumento14 pagine99 Racz Irma PaperMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Pemikiran StrategikDocumento2 paginePemikiran StrategikMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic Planning Using Hoshin KanriDocumento10 pagineStrategic Planning Using Hoshin KanriWinner#1Nessuna valutazione finora

- McKLean Rapid DesignDocumento9 pagineMcKLean Rapid DesignMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Kaizen Lean Management Service Sector2Documento22 pagineKaizen Lean Management Service Sector2Mahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Pengurusan PerubahanDocumento8 paginePengurusan PerubahanMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Mit16 660jiap12 3-6Documento27 pagineMit16 660jiap12 3-6Mahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Surat Siaran Urusan Pemangkuan Guru Cemerlang Dan Pensyarah Cemerlang Tahun 2014Documento11 pagineSurat Siaran Urusan Pemangkuan Guru Cemerlang Dan Pensyarah Cemerlang Tahun 2014mrdanNessuna valutazione finora

- Kriteria Penilaian NTExICC2013Documento1 paginaKriteria Penilaian NTExICC2013Mahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Theory-Based Instructional Models Applied in Classroom ContextsDocumento10 pagineTheory-Based Instructional Models Applied in Classroom ContextsMahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- Summative Test 12 Sains Tahun 5Documento7 pagineSummative Test 12 Sains Tahun 5Mahathir FansuriNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Heqmal Razali CVDocumento1 paginaHeqmal Razali CVOchadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Spencer Glatt - Consultant Agreement - Please Have Consultant Sign - 2816200 1Documento2 pagineSpencer Glatt - Consultant Agreement - Please Have Consultant Sign - 2816200 1api-535837127Nessuna valutazione finora

- Transfer Goal & Unpacking DiagramDocumento1 paginaTransfer Goal & Unpacking DiagramClevient John LasalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Esl Siop SpanishDocumento2 pagineEsl Siop Spanishapi-246223007100% (2)

- Name: Jee Anne Tungpalan Teacher: Mr. Jonel Barruga Grade & Section: BEED-IIC Date: May 28,2020Documento2 pagineName: Jee Anne Tungpalan Teacher: Mr. Jonel Barruga Grade & Section: BEED-IIC Date: May 28,2020Jonel BarrugaNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Affecting The Utilization of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of Hiv Among Antenatal Clinic Attendees in Federal Medical Centre, YolaDocumento9 pagineFactors Affecting The Utilization of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of Hiv Among Antenatal Clinic Attendees in Federal Medical Centre, YolaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Games and Economic Behavior Volume 14 Issue 2 1996 (Doi 10.1006/game.1996.0053) Roger B. Myerson - John Nash's Contribution To Economics PDFDocumento9 pagineGames and Economic Behavior Volume 14 Issue 2 1996 (Doi 10.1006/game.1996.0053) Roger B. Myerson - John Nash's Contribution To Economics PDFEugenio MartinezNessuna valutazione finora

- E-Shala Learning HubDocumento8 pagineE-Shala Learning HubIJRASETPublicationsNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan PeDocumento7 pagineLesson Plan PeSweet Angelie ManualesNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of OC and LeadershipDocumento8 pagineImpact of OC and Leadershiperrytrina putriNessuna valutazione finora

- Engineeringstandards 150416152325 Conversion Gate01Documento42 pagineEngineeringstandards 150416152325 Conversion Gate01Dauødhårø Deivis100% (2)

- MRR Format For GED109Documento1 paginaMRR Format For GED109Cyrus VizonNessuna valutazione finora

- TO Questioned Documents: Darwin P. Batawang, Ph.D. CrimDocumento54 pagineTO Questioned Documents: Darwin P. Batawang, Ph.D. Crimako si XianNessuna valutazione finora

- SITRAIN Brochure Sep 12 PDFDocumento6 pagineSITRAIN Brochure Sep 12 PDFPaul OyukoNessuna valutazione finora

- Life Cycle Costing PDFDocumento25 pagineLife Cycle Costing PDFItayi NjaziNessuna valutazione finora

- Training - Development Survey at BSNL Mba HR Project ReportDocumento74 pagineTraining - Development Survey at BSNL Mba HR Project ReportSrinivasa SaluruNessuna valutazione finora

- Group Communication - Notice, Agenda, Minutes: Chethana G KrishnaDocumento36 pagineGroup Communication - Notice, Agenda, Minutes: Chethana G KrishnaKoushik PeruruNessuna valutazione finora

- Aruba SD-WAN Professional Assessment Aruba SD-WAN Professional AssessmentDocumento2 pagineAruba SD-WAN Professional Assessment Aruba SD-WAN Professional AssessmentLuis Rodriguez100% (1)

- Name of Student: - Prefinal Assignment No.1 Course/Year/Section: - Date SubmittedDocumento2 pagineName of Student: - Prefinal Assignment No.1 Course/Year/Section: - Date SubmittedJericho GofredoNessuna valutazione finora

- RPMS SY 2021-2022: Teacher Reflection Form (TRF)Documento3 pagineRPMS SY 2021-2022: Teacher Reflection Form (TRF)Argyll PaguibitanNessuna valutazione finora

- Sft300 - Project Del.1 - Spring 22 2Documento4 pagineSft300 - Project Del.1 - Spring 22 2Ahmad BenjumahNessuna valutazione finora

- Gabriel FormosoDocumento3 pagineGabriel FormosoMargaret Sarte de Guzman100% (1)

- Pronunciation in The Classroom - The Overlooked Essential Chapter 1Documento16 paginePronunciation in The Classroom - The Overlooked Essential Chapter 1NhuQuynhDoNessuna valutazione finora

- Performance Management & ApraisalDocumento22 paginePerformance Management & ApraisalKaustubh Barve0% (1)

- Final Moot Court Competition Rules of ProcedureDocumento4 pagineFinal Moot Court Competition Rules of ProcedureAmsalu BelayNessuna valutazione finora

- Foresight PDFDocumento6 pagineForesight PDFami_marNessuna valutazione finora

- Advocacy and Campaigns Against Drug UseDocumento4 pagineAdvocacy and Campaigns Against Drug UseaudreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Rizal As A Student (Summary)Documento5 pagineRizal As A Student (Summary)Meimei FenixNessuna valutazione finora

- Vb-Mapp Master Scoring Form: Level 3Documento11 pagineVb-Mapp Master Scoring Form: Level 3Krisna Alfian PangestuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Digital Cities Challenge: Designing Digital Transformation Strategies For EU Cities in The 21st Century Final ReportDocumento119 pagineThe Digital Cities Challenge: Designing Digital Transformation Strategies For EU Cities in The 21st Century Final ReportDaniela StaciNessuna valutazione finora