Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Narration

Caricato da

Jacob LundquistCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Narration

Caricato da

Jacob LundquistCopyright:

Formati disponibili

"A World Complete in Itself": Gatsby's Elegiac Narration Author(s): Dan Coleman Source: The Journal of Narrative Technique,

Vol. 27, No. 2 (Spring, 1997), pp. 207-233 Published by: Journal of Narrative Theory Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30225466 . Accessed: 21/02/2014 01:42

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Journal of Narrative Theory and Department of English Language and Literature, Eastern Michigan University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Narrative Technique.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

"AWorldComplete In Itself":Gatsby'sElegiac

Narration

DanColeman

The only general attributeof projectedromance . . . is the fact [that it deals with] experience disengaged, disembroiled,disencumbered,exempt from the conditions that we usually know to attachto it The balloon of experienceis in fact of course tied to the earth,andunderthatnecessity we swing, thanksto a ropeof remarkable carof the imagilength,in the moreorless commodious nation;but it is by the rope we know where we are, and from the momentthatcable is cut we are at largeand unrelated .The art of the romanceris, 'for the fun of it,' insidiously to cut the cable, to cut it withoutour detectinghim.-Henry James,prefaceto The American [I]n my new novel I'm throwndirectlyon purelycreativeworknot trashyimaginingsas in my stories but the sustainedimagination of a sincereandyet radiant world.-F.E Scott Fitzgerald,letter to Maxwell Perkins'

Nick Carraway beginshis storyby describinghow it will end. "Gatsbyturned

out all right," he explains, " it is what preyed on Gatsby, what foul dust

floated in the wake of his dreamsthat temporarilyclosed out my interestin the abortive sorrowsand short-windedelations of men" (6-7). By insisting from his narrative's outset on its hero's happyending, Nick sets for himself an essentially elegiac ambition:to ensure that his readerscome to the last page of the novel convinced thatGatsbyis "somethinggorgeous"(6). At the end invites us same time, the claritywith which Nick defines his narrative's to considerthe rest of his storyas a means,to studythe functionsof its form,

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

208

to consider how-and how well-Gatsby's parts cooperate or conflict with the achievement of its whole. By taking our bearings from Nick's clearly articulated purpose, we might steer clear of the twin perils described by Roman Jakobson in his critique of "linguist[s] deaf to the poetic function of language and... literary scholar[s] indifferent to linguistic problems" (377). That is to say: the telos by which Nick tries so intently to organize his narrative offers us an excellent opportunity to explore how a novel's formal structures create its aesthetic effects. However, the attempt to identify Nick's elegiac ambition with Gatsby's informing design poses serious problems: neither Nick's sense of Gatsby's happy ending nor his ability to persuade us of it turns out to be as sure and

stable as at first they seem. Returnedto its context, Nick's affirmationof Gatsby's ultimate success suggests his underlying uncertainty;within the

speech in which it occurs, the clear note of Nick's assertion begins to quaver: [T]herewas somethinggorgeousabout[Gatsby]... a romantic readinesssuch as I have never found in any other person and which it is not likely I shallever find again.No-Gatsby turned out all right at the end; it is what preyed on Gatsby,what foul dust floated in the wake of his dreamsthat temporarily closed out my interestin the abortivesorrowsand short-windedelations of men. (6-7) The sentence that ends by insisting on Gatsby's distinction from the corruption which surrounded him, begins by responding to a question that hasn't been asked (No-Gatsby turned out all right at the end). Nick's triumphant declaration of his hero's happy ending must overcome his own equivocation;

it is not simply an assertion but an answer.Althoughostensibly alone, Nick protests as if defending his claim against anotherspeaker."To whom," we might wonder,"is Nick saying 'No'?" It might be thatNick respondsto a silent partof himself, a skepticalinner voice so forceful that Nick must deny it "aloud."If so, Nick's "No" reveals the sense in which this narrator's to makinghis hero turnout all commitment cannot be from his right separated uncertaintyabout whetheror not Gatsby really did. Fromthis perspective,the same tension exposed by the content of Nick's closing speech-i.e., Nick's immenseadmiration for a man who "representedeverythingfor which [he has] an unaffectedscorn"-shows up in its voice (7).2 dialogic form, throughthe crack in Nick's narrative

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration inGatsby Elegiac

209

Drawn back-and-forth between fascinationand skepticism,Nick's story is simultaneouslyan elegiac fiction that aims to make sure that everything turnsout all right-and a "historyof the summer" thattries to make sense of what really happened(10). In this respect,the ambivalenceof Nick's narrative is matchedby the precariousness of his narratorial Because he authority. is not only the ostensible writerof this story but a characterwithin it, Nick lacks a privilegedposition outsidethe fiction's frame.Unlike a more powerful author,Nick cannot ensure that any apparentcompetitionwith his own Last Wordis reallyjust a game whose outcome has been decided ahead of time, a fight rigged from the start. Since Nick's narrativevoice can never completely transcendthat plane on which the other charactersspeak-nor silence thatskepticismin himself which whispersagainstany simple faith in is always uncertainand his ability his hero-Nick's controlof the narrative to bringGatsbyto a happyending is always in doubt.Any power Nick may possess to make Gatsbyturnout all rightis not given but accomplished;any ring of authorityhis words may achieve will never be pure but, instead, always colored by his struggleto achieve it. The historyof the summer,then, to find a voice with which is also the historyof Nick's attemptsas a narrator he can conjure aroundhis hero "a world complete in itself" where "[e]ven Gatsbycould happen"(110, 73). (Recon)figuring the Facts: Metaphoric Worlds With this uncertain"sense of an ending"before his eyes, Nick opens his story by identifyingits origin: "andthe historyof the summerreally begins on the evening I drove over thereto have dinnerwith the Tom Buchanans" (10).3However,Nick's descriptionof "thewhite palacesof fashionableEast Egg glitter[ing]along the water"seems less the materialof history thanthe stuff that fairy tales are made of (10). Unable or unwilling to draw clearly those boundarieswhich distinguishthe Actual from the Imaginary,Nick's narrative begins by creatingan uneasy commercebetween the two. Compelledby Tom into the living roomof his fashionableEast Egg mansion, Nick enters a "bright,rosy-coloredspace"in which

The only completely stationaryobject . .. was an enormous

werebuoyed couchon whichtwoyoungwomen upasthough balloon. were both in white andtheir an anchored They upon

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

210

dresses were ripplingand flutteringas if they had just been blown back in after a short flight aroundthe house. I must have stood for a few momentslistening to the whip and snap of the curtainsand the groan of a pictureon the wall. Then there was a boom as Tom Buchananshut the rear windows and the caughtwind died out aboutthe room and the curtains and the rugs and the two young women ballooned slowly to the floor. (12) The conceit of the balloon, which begins with a simile's qualifications (as if, as though), moves through the collocation created by the "whip and snap of the curtains" and the hyperbolic "groan of a picture on the wall" to end by almost escaping its figurative tethers. Over the course of Nick's description, the balloon-like couch becomes a couch-balloon that settles-like any real

balloon would-because the wind which suspendedit has died out. That is to say: a metaphorwhich is initially, obviously impossible (we know that couches can't really float) andclearly subordinated to the realityit describes the is us understand the sense in which the as to (i.e., image supposed help couch "floats")ultimatelybecomesentirelyplausible,existingindependently in that strangenew world the metaphormakes. In otherwords, this passage takes its readersfrom a "realistic" place where a simile can fancifully compare a couch to a balloon, to a world in which there really are couch-balloons-a magical universe furnishedwith facts entirely alien to ours, but regulated by wholly familiar laws of cause and effect. Nick's description reverses the usual literal-figurativehierarchy;his fantastic trope momentarily warpsreality aroundit. Like "the fresh grass outside that seemed to grow a little way into the crosses thatboundarywhich separatesthe ordinary house,"Nick's metaphor from the fantastic, warpingthe novel's world by means well-describedby

Dorothy Mack (12). "Metaphoring," she argues, "is . . . more than saying

something;it is fabricatinganother'reality.'In choosing to extend the scope

of a particular presupposition to a particular topic, the speaker imposes a way of seeing, feeling, connecting, and judging; he forces his unique and momentary 'world-creating' and 'contrary-to-fact' perspective on the hearer" (84). Along similar lines, Samuel Levin has suggested that most readers, when faced by a metaphor that misrepresents what they know to be true of the world, typically revise their construal of the literal meaning of the words (e.g., "her lips are not really roses, but red in the way that roses are"). Read-

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration in Gatsby Elegiac

211

ers have, however,anotheroption:insteadof treatingtheirideas of the world as stable and the metaphor'smeaning as changeable, they can "[take] the metaphoric expressionliterallyand[accept]the epistemological consequences that ensue" (MetaphoricWorlds4): states of affairs cannot beconceived [A]lthough preternatural as actually of theirexistingcan be existing,the possibility conceivedof: We can forma conception of whatthe world wouldhaveto be likewereit in facttocomprise suchstatesof affairs.... If we readin a poem"thesky is angry," we conceiveof a worldin whichtheskymight be angry; in thesame the starshappy, andso on. way,the windmightbe hungry, Theusualprocessof construal of instead is simplyinverted; thatconsists in aninterpretation withconditions constructing we construct to theactual theactual onethatconforms world, In consequence of the utterance. whatemergesas language inwhich thepoemis expressed, is notthelanguage metaphoric hascaused us to project. Wehave buttheworld thatlanguage into a world. ourselves 121") projected metaphoric ("Language This world wherelanguageis takenliterallyis one in which Nick's narrative invites us to spendmuch of ourreaderlytime. Throughout the novel, the transformativeeffects of Nick's metaphorsare reinforcedby his habit of changing similes which compareA and B into metaphorswhich equate A and B-or even into substitutions by means of whichA takes the place of B. This tendency to take rhetoricalfigures "seriously"marksNick's narrative from its beginning; within the scope of a single page in the first chapter, Jordanis transformed-like the couch that briefly "becomes"a balloonfrom someone whose chin is "raiseda little as if she were balancingsomethat thing on it" into "thebalancinggirl."At the same time, the "something" Jordanseemed to Nick to be balancing-which initially exists only hypothetically as an analogy that Nick draws for his readers ("her chin [was] raised a little as if she were balancingsomethingon it")4-becomes an actual presence within that story-worldsharedby Nick and the novel's other "theobject she was balancinghad obviously tottereda little and characters: her somethingof a fright"(13). given The process of "takingliterally"by which Gatsby's metaphorsdisrupt ourreaderlyexpectationsis insightfullyanalyzedby LeonardPodis. "[M]ost of Nick's markedlyanti-realisticmetaphors," he argues," ... take place in

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

212

the contexts of what seem to be nearly surrealexcursions.The metaphors usually occur in clusters,such thatthe experienceswhich are being set forth attain almost visionary status"(64). In the clusters that Podis analyzes, a series of "non-rational" metaphors pile one uponthe next untiltheiraccumulationof incredibleclaimsbeginsto outweighthereader'ssense of the novel's realism.Nick's descriptionof Gatsby'sultimatevision exemplifies this overwhelming: He musthavelookedup at an unfamiliar sky through frightening leaves and shiveredas he found what a grotesquething

crewasuponthescarcely a roseis andhowrawthesunlight

ated grass. A new world, materialwithoutbeing real, where

likeair, about dreams drifted poor ghosts, breathing fortuitously

... like thatashen,fantasticfiguregliding towardhim through

theamorphous trees.(quoted in Podis63) "Theepithetsemployedhere,"Podis argues," 'unfamiliar sky,' 'frightening leaves,' 'grotesque .. rose,' 'raw sunlight,' and 'scarcelycreatedgrass'are all metaphoricalin that the adjectives are to a degree ... incompatible with the nouns they modify" (63-64). While not "radically"non-rational, Podis contends, these "semanticclashes"begin to "challengeour ability to (69, 64). Not, however,until the second half conceptualizethem rationally" of the passage does Nick's mix of metaphorsstart to disturbhis readers' withinthe novel sense of the basic continuitybetweenthe realityrepresented and the one they're used to. Though spelled out clearly, the analogy which asks us to imagine ghosts "breathingdreams like air" makes no ordinary sense; dreamshave no qualitiesin commonwith the stuff we breathe:"None which come attachedto the term 'dreams'will match of the presuppositions The only alternative[left to the up with the specificationsof the metaphor. reader]is to createnew suppositionsabout 'dreams,'suppositionswhich involve a highly subjective way of seeing" (64). Nick's reportof a "figure gliding..,. throughthe trees"createssimilarkinds of difficultiesfor readers trying to construeit: "The presuppositionsattachedto 'gliding' will allow the word to be applied to a person on a dance floor, but the stretchingof vision to connect this action with a gunmanstalkinghis humantargetproduces a bizarre,distortedeffect" (64). However, Podis's illuminatingstudyfails to accountfor the full rangeof A more complete analysis would powers exercised by Gatsby'smetaphors.

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration inGatsby Elegiac

213

also shed light on how these figures can "worktogether"not only cumulatively, but cooperatively.Podis's explanationof how Nick's weird descriptions can addup to "causeeverydayrealityto disintegrate into an amorphous the in which can also cause the novel's other-world"overlooks ways they fantasticreality to hold together(64). For example: while the premises underlyingNick's descriptionof Daisy and Jordan'scouch-balloonare indeed the logic which informs this other-worldis both familiar "other-worldly," and coherent. In the same way, there is an internalconsistency that binds togetherNick's earlydescriptionof the novel's landscape,andmakesit seem not so unreasonablethat there should be "a pair of enormouseggs" in "the of Long IslandSound"(9).5 great wet barnyard "Eggs"is attractedto "barnyards" by the same force that binds together the figure underlyingthe image of gentle ballooning which runs beneath Nick's descriptionof Daisy and Jordanon the couch. As W. J. Harvey excontinuea nauticaltheme which begins in plains, "buoyed"and "anchored" Homericallusion (wine-coloredrug) and extends the precedingparagraph's of the women's dresses,the "whipand snap into the "ripplingandfluttering" of the curtains" andthe "groanof a pictureon the wall."6 Thematicallyinterrelated, all of these words are part of the same linguistic "collocation,"a term nicely explainedby RonaldCarteras "thecompanyhabituallykept by a word"(159).7Like a conversationbetweenparanoiacswhose perspectives like the crazy banter are warpedin exactly the same way (or alternatively: that bounces between the guests aroundthe Mad Hatter'stea table) the visions of the world presentedby Gatsby'sfantasticmetaphorsgrow compelling by theirconsensus.And the more successfullythey collude together,the more likely we are as readersto take their common fantasy for granted,to considera couch floatinglike a balloon or a lawn runninglike a horse as not particularlyunusual.That is to say: Nick's metaphoricalnetworks, while excursions" The "surreal arenot always"non-rational." often "anti-realistic," invitehis readersmay takethemto a place whose on which Nick's metaphors claims of the "unreality"is made coherent by the mutually corroborating constitute it which (Gatsby 105). metaphors Recalcitrant Railroads, Ash Men, and the Eyes of T. J. Eckleburg: Animate Landscapes in the Valley of Ashes Indeed,those fantasticworldscreatedwithin Nick's extendedmetaphors threatenat times to take over the novel's realityaltogether:

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

214

J N

Abouthalfwaybetween WestEggandNew York themotorroadhastily andrunsbesideit fora quarter joinstherailroad of a mileso as to shrink desolate areaof awayfroma certain land.Thisis a valleyof ashes-a fantastic farmwhereashes growlike wheatintoridgesandhills andgrotesque gardens, where ashestaketheforms of houses andchimneys andrising smoke andfinally, witha transcendent of menwhomove effort, thepowdery dimlyandalready crumbling through air.... thegreylandandthespasms Butabove of bleak dustwhich driftendlessly overit, youperceive, aftera moment, theeyes Theeyes of Dr.T.J. Eckleburg are of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg. blueandgigantic-theirretinas areoneyardhigh.Theylook out of no face but,instead, froma pairof enormous yellow whichpassovera nonexistent nose.(27) spectacles Froman opening thatlocates the Valley in relationto at least one real place, Nick's descriptionmoves throughmild personificationinto unconstrained of a road which animism.Not content with the subduedanthropomorphism the so as to shrink from the waste land, the "hastilyjoins away" railroad..,. literalizesthe landscape'spreviouslyfigurativepersonality, endownarrative ing it with not merelythe powerto act like humanbeings, butthe unqualified ability to become them.s the readeris instructed While surveyingthis allusion-turned-landscape, with almost hypnoticrepetition:"Youperceive, aftera moment,the eyes of Dr.T. J. Eckleburg.The eyes of Dr.T. J. Eckleburgareblue."Describedwith the precision of a driver's license (eyes: blue; retinas:one yard high) and assigned a flatly declarativeagency (They look out of no face), these eyes existence untilat least the passage's maintaintheirfantasticallyindependent facelessness size and when their end, begin to resolve into a realimpossible istic explanation:"Evidentlysome wild wag of an oculist set them there to fattenhis practice"(28). However,the extrapolated opticianhas left town by the time of the story's telling, and only his sign remains to "broodon over the solemn dumping ground"-an inscrutablespirit above a vast abyss of ashes which delivers forthmen only by the most transcendent figuraleffort.Withits referentdead or moved away, the billboardhas become a floating signifier;disconnected from the authorof its meaning,it lies open to infinite interpretation:

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

in Gatsby ElegiacNarration "Godsees everything," Wilson. repeated anadvertisement," "That's Michaelis assured him.(167)

215

Like this oculist abscondituswho is simultaneouslythe advertisement's referent and its creator,Nick is both subject and authorof a signifier which must exist without his being there to guaranteeits significance (i.e., that Gatsby turnedout all right at the end). From this perspective,Nick's firstperson narration might be understoodas an attemptto put some semblance of authorialpresencebehindhis sign.

Gatsby'sBodilyDouble:MyrtleWilson'sGraphicRealism

The cable-cuttingfantasyof the Valley,however,is broughtsharplydown to earthby Tom Buchanan'smistress,whose vivid "incarnation" brings into the novel an insistentfacticity dynamicallyopposedto Gatsby'sunutterable visions. Fromthe momentof her descent from the rooms which Nick imagines as "sumptuousand romantic apartments. . . concealed overhead," Myrtle's "thickishfigure" "block[s] out the light" in "the shadow of a garage.""[W]alkingthroughher husbandas if he were a ghost,"Myrtle smolders in the midst of an otherwiseburnt-outlandscape,the only presence in the Valley substantialenough to escape the overhangingveil of ashes (2930). Whereasour first sight of Gatsbytells us little more than what his posture suggests to Nick's far-awayperspective (a glimpse of arms stretched tremblingtowarda green light distantover darkwater), Myrtle is immediately given to us fully realized in all her bodily magnificence-"[carrying] hersurplusflesh sensuously" in a "spotted dressof darkblue crepe-de-chine"; shakinghands, wetting her lips, commandingher husbandand her lover. In this contrast, the novel sketchesout the meannessof JamesGatz's sharpening of Gatsby's,while ensuringthat life only afterit has shown us the grandeur the barrencircumstanceswhich drive Myrtle's ambitionare the first thing we learnabouther.Immediatelydefinedby hercontext-her husband,sister and friends;her history;the way she decoratesher house-Myrtle is bound into the physical world aroundher;Gatsby,on the otherhand,is given to us "atlarge and unrelated" in a way thatleaves him much freerto slip from the realistic and into the allegorical.Nonetheless, Myrtle's sharpsense of purpose draws her close to Gatsby; she too is a "[boat] against the current" (189). Balanced on the intensityof their common desire to escape their re-

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

216

spective origins, the novel's motion mightbe figuredas a rockingback-andforth between the concrete realismof Myrtle'sstory and the indefinite fantasy of Gatsby's. From Myrtle's perspective deep in the ashes of the wasteland, Tom Buchananrepresentsthe possibility of escape, the power to acquireall the goods on "the list of things [she's] got to get. A massage and a wave and a collar for the dog and one of those cute little ash trays where you touch a spring,and a wreathwith a black silk bow for mother'sgrave that'll last all summer"(41). The most precisely described location in the novel, all the rooms in Myrtle's apartment are small, and her living room is "crowdedto the doors with a set of tapestriedfurniture entirelytoo large for it so thatto move aboutwas to stumblecontinuallyover scenes of ladies swinging in the detail othergardensof Versailles"(33).9Filled with the kind of "realistic" wise absent from Nick's descriptions-an "over-enlarged photograph,apparently[of] a hen sitting on a blurredrock,""old copies of 'TownTattle'" lying on the table, Catherine's"solidsticky bob of red hair,""theremainsof the spot of dried lather" adhering to Mr. McKee's cheek, a dog biscuit "decompos[ing]apatheticallyin [a] saucer of milk"-Myrtle's apartment, unlike every othersetting in the story,is renderedwith a graphicspecificity a set designer could accuratelyreproduce(33, 34, 41). Speech, too, gains an almostphysicalpresenceat Myrtle'sparty.Whereas the ineffable thrillof Daisy's voice leaves behindboth words and the world to which they mightrefer("Ihadto follow the soundof [Daisy's voice] for a moment,up anddown, with my ear alone before any wordscame through"), Myrtle's speech bears her body with it: "Myrtlepulled her chair close to mine and suddenlyher warmbreathpouredover me" (90, 40). At the same time, conversationundergoesa similar incarnation,sinking from the ethereal brillianceof Daisy and Jordan'sintricatebanterto the dull vulgarityof exchange with her sister and Mrs. McKee: Myrtle's ultra-mundane "Ihada woman up herelastweekto lookat my feet and when she gave me the bill you'd of thoughtshe had my [sic]out." appendicitus "What wasthenameof thewoman?" askedMrs.McKee. feet "Mrs. Eberhardt. Shegoesaround atpeople's looking in theirownhomes."

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration inGatsby Elegiac

"I like yourdress," remarked Mrs.McKee."I thinkit's adorable." (35)

217

So insipid thatit soon promptsTomto yawn "audibly," dialoguein Myrtle's moves between apartment gracelessly clumsy speakersand subjectswhose indelicacy (bills, appendicitus,feet) and discontinuity(Mrs. McKee's completely off-topic remarkaboutMyrtle'sdress) would never be allowed in to East Egg's elegantly choreographed repartee(36). This mood of overcrowdingand crudenessgrows strongeras Nick gets drunkerand Myrtle takes up more and more of the space in her apartment: "Herlaughter,her gestures, her assertionsbecame more violently affected momentby momentand as she expandedthe room grew smalleraroundher untilshe seemedto be revolvingon a noisy,creakingpivot throughthe smoky air"(35). At Myrtle'sparty,the gearsshow; the splendorwhich momentarily vanishes from Gatsby's face to reveal "an elegant young rough-neck whose elaborateformalityof speech almost missed being absurd"lies beyond the reachof Myrtle'sviolent affectations(53). In that strictlytangible world she dominatesby the magnificence of her body and the intensity of her desire, Myrtlecan accomplishno more thana physical expansion. Nor does Nick's narration in any way assist Myrtle'stranscendence: if it is relativelyeasy to visualize the balloon to which Daisy andJordan'scouch is compared,it's not at all clearwhatkindof thingMyrtleis supposedto look like as she spins on her pivot.10 Still bound to the earth,Myrtle's metaphor fails to achieve the independentintelligibilitythatdistinguishesmore viable analogies; the "incoherentfailure"of Nick's image draws our attentionto the distance between Myrtle's materialcondition and the possibilities for romancewhich exist beyond it (188). Lacking Gatsby'stheatricalability to make somethingspectacular of himself andhis world-to transform the fundamentalterms of his reality and thereby elude the limits they imposeMyrtle swells to enormousproportionswithoutever becoming larger-thanlife. ThroughNick's deepeninghaze, Myrtle'spartygrows increasinglymore incomprehensible: calledupseveral peopleon Sittingon Tom'slapMrs.Wilson thetelephone; thentherewereno cigarettes andI wentoutto WhenI cameback buysomeat thedrugstoreon thecorner. so I sat downdiscreetly in the living they haddisappeared

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

218

of "Simon it roomandreada chapter CalledPeter"--either was terrible stuffor the whiskeydistorted thingsbecauseit didn'tmakeanysenseto me. (33-34) Joined by transitionsthat obscure causation(then there were no cigarettes; A foland I went out; when I came back), events seem strangelyunrelated; reason.The tenorof the scene soon swings out of the lows B for no apparent made plans confused and into the chaotic:"Peopledisappeared, reappeared, to go somewhere, and then lost each other, searchedfor each other, found each other a few feet away"(41). Then Tom breaksMyrtle'snose and Nick leaves a tableau dominatedby a "despairingfigure on the couch bleeding fluently"andtryingto spreada copy of 'TownTattle'over the tapestryscenes of Versailles"(42). Compelled by Tom to attendMyrtle's partyand to abandonan "almost pastoral"vision of the city (complete with the promise of "a great flock of white sheep" waiting aroundthe corner)Nick proves equally unable to excuse himself once he's there (32). "[C]alled... back into the room"by the "shrillvoice of Mrs. McKee,"Nick is denied escape to a sky he imagines as and is drawnagain into the fiercely "the blue honey of the Mediterranean" be somewhereelse: mundaneweb of Myrtle'sparlor(38). Nick would rather toward thepark I wanted to getoutandwalkeastward through to go I became thesofttwilight buteachtimeI tried entangled whichpulledme back,as if in somewild strident argument Yethighoverthe city ourline of withropes,into my chair. theirshare of human musthavecontributed yellowwindows andI in the darkening streets, secrecyto the casualwatcher I was withinand was him too, lookingup and wondering. andrepelled enchanted without, simultaneously by the inexof life. haustible (40) variety If not simply repelled by what is happeningat Myrtle's party,Nick is attractedto the life aroundhim only when imagininghis distancefrom it. For Nick, the furiousconfusionof Myrtle'spartyrepresentsa concertedeffortto him (39). As force him to "play a part"in the too-real dramasurrounding his attemptsto gain the distancea reader-or an authorsuch, it frustrates needs in orderto give significantshapeto "theinexhaustiblevarietyof life."

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

inGatsby Narration Elegiac Trimalchio's Banquet:A WorldCompletein Itself

219

Whereas the chaosof Myrtle's in munpartyleavesNick "entangled" danedetail,Gatsby's partyofferswhatHenryJamescalls an "experience disembroiled, disencumbered, [and]exemptfromthe condidisengaged, we know to attach to it." The detachment Nickdiscovers tionsthat usually on Gatsbyand no Frenchbob in his hero-"no one swoonedbackward shoulder andnosinging wereformed withGatsby's touched Gatsby's quartets which makes link"-is same isolation headfor one the possiblehis party's men andgirls cameandwent almostallusivepoise:"Inhis blue gardens like mothsamongthewhisperings andthe stars" (55, 43). Yet,in orderfor Nick-the-narrator needs tohappen around Nick-the-character, Gatsby's party to succeed, Nickmust In order forhis elegiacambitions to makeit happen. in itself' (110). ourassentto a "world complete conjure If Gatsby's party-assembledeveryfortnight by "a corpsof caterers" so muchas a theoutof "canvas" and"colored nothing lights"-resembles of its audithe mostenthusiastic member aterset, Nick is simultaneously formaking surethatnobodywonence andthe stagemanager responsible dersaboutthe missingfourthwall (44, 43). In orderto achieveGatsby's Nick's his magnificent andmakecredible Belasco-like"triumph" fakery, andthe gardeners mustworkas hardas thecaterers narration puttogether

(50):

from five crates of oranges andlemonsarrived EveryFriday a fruiterer in NewYork-everyMonday thesesameoranges of pulpless halves. andlemons lefthisbackdoorina pyramid whichcouldextract the Therewas a machine in thekitchen if a littlebutton inhalfanhour, oranges juiceof twohundred thumb. waspressed twohundred timesby a butler's (43-44) The butlerdoesn'tpressthe button;the buttonis pressedby a butler'sthumb: like the magician'sotherhand,Nick's rhetoricalfiguredivertsour attention

fromeverything aboutthe butlernot includedin his representative part. This seeminglyexplicitaccountof the originsof the juice consumedat

Gatsby'spartyobscuresentirelythe agency of those responsiblefor making

as oranges andlemonsandleaveas emptypeels.Thebutton thefruitarrive for moveandmarvelous is pressed andunseenmechanisms thingshappen

no reason we can see; by hiding the connection between effects and their

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

220

causes, Nick's recurrent use of synecdoche casts over Gatsby's party the spell of inexplicability. Like a bouncer checking invitations, this exclusive trope keeps out of the party everything that distracts from its essential riot: "A tray of cocktails floated at us through the twilight and we sat down at a table with the two girls in yellow and three men, each one introduced to us as Mr. Mumble" (47). Disconnected from any person carrying them, the drinks can appear without reminding us of the waiter who will walk offstage and into a life of his own as soon as the curtain falls. In the same way, Nick almost entirely obscures the other guests at the table-eliminating all those features that play no part in the effect he's creating-to leave as synecdochical distillates their single aspect of color (the two girls in yellow) or peculiarity of speech (Mr Mumble).12 Reigning over West Egg is a sense of unreality, a strangeness of tone partially accomplished by the sudden shift of tense by means of which Nick drives his story into the present. After a paragraph which details the preparations for Gatsby's party, Nick swerves without warning into the present perfect: "By seven o'clock the orchestra has arrived," he tells us, without any explanation of how the band-or the narrative-got there (44). Gatsby's party

is filled with things which seem to exist only in the present:

The last swimmershave come in from the beach now and are the carsfromNew Yorkareparkedfive deep dressingupstairs; in the drive,and alreadythe halls and salons andverandasare colors andhairshornin strangenew ways gaudy with primary and shawls beyond the dreamsof Castille. (44)

of its parts,this parade to emphasizethe simultaneity Paratactically arranged of phenomenaleaves no trackswhich mightlead backto the past fromwhich is without any explanation it came. Everythingat Gatsby'sparty"already"

of how it got to be that way. There is no chain of causes leading out from the

this is a world of effects only, "a "now"and into an historicalbackground; thing that merely happened"for no apparentreason: "People were not invited-they went there.They got into automobileswhich bore them out to Long Island and somehow they ended up at Gatsby'sdoor"(78, 45). Alone in even the immediatepastamonga crowdof guestsperfectlyuninterested who "acceptedGatsby'shospitalityandpaidhim the subtletributeof knowing nothing whatever about him"-only the guest called Owl Eyes cares

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration in Gatsby Elegiac

221

about origins and causes: "Whobroughtyou," he asks Nick and Jordan," ... Or did you just come? I was brought.Most people were brought"(65, 50). As we learn later at Gatsby's funeral, Owl Eyes is also the only one besides Nick who cares about Gatsby;in this respect there seems to be a connection between the skeptical fascinationand the compassion both he and Nick feel for Gatsby. Unmarkedby the conditionsof its creation,Gatsby'spartysprings"from [its] Platonicconception";like the "city... all built with a wish out of nonolfactorymoney,"Nick's magnificentfabricationfloats free from any trace of the smell of sweat (or worse) involved in its construction(104, 73). In this respect,the accomplishment of Gatsby'spartyexemplifies what Henry James describes as the essential artisticact: "Really,universally,relations stop nowhere,andthe exquisiteproblemof the artistis eternallybut to draw, by a geometryof his own, the circle withinwhich they shall happilyappear to do so."'3 The Rock of the World and the Fairy's Wing: Escape versus Transformation No such circle exists aroundMyrtle'spartyto obscureits relationsto the rest of the world. Whereas Gatsby's revelry transfiguresthe materialsof real life into theater,Myrtle'ssmall rooms aredominatedby a strictlyrepresentativephotography, Point-the by pictureswhose titles (e.g., "Montauk Gulls" and "Montauk Point-the Sea") suggest a perfectlyliteraltreatment of theirsubjects.Indeed,Tom'sparodyof McKee's style of titling-"George B. Wilson at the Gasoline Pump"-sounds like nothingso much as a newspaper caption (37). Although the guests at Myrtle's partytalk a lot about how Mr. McKee might "makesomethingof" his subject matter,he seems largely uninterestedin a kind of art that would significantlytransformhis materials(36). Nick hints at the povertyof McKee's creativityin the simile by which he describeshim: "Mr.McKee was asleep on a chairwith his fists of a man of action"(41). In the same clenched in his lap, like a photograph that McKee can become a just by coming to rest, he can way photograph makeone by simply holdinghis subjectstill. As RobertEmmetLong puts it: "If the role of the artistis to achieve a vision underlyingthe inchoatematerial of reality,McKee is an artistmanqud,who recordsonly surfaces.Of his wife..,. he has takenone hundredtwenty-sevenphotographs,a figure that, in its exactness, emphasizes the hopeless literalnessof his mind" (108-9).

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

222

J N

One might add that the number of photos, by its magnitude, also emphasizes McKee's failure to isolate the essence of his subject in an interpretive portrait. Unable to make artistic value out of the facts he's given, McKee is left trying to record the "inexhaustible variety" of his wife's changing appearance in a potentially infinite series of snapshots. That is to say: this photographer lacks the aesthetic control which keeps an author from slipping into what Roland Barthes calls "a downward spiral into endless detail": [W]hendiscourseis no longerguidedandlimitedby the structural imperativesof the story . . . there is nothing to tell the detailsat one pointrather writerwhy he shouldstopdescriptive than another:if it was not subject to aesthetic or rhetorical there wouldbe inexhaustible choice, any"seeing" by discourse; would always be some corner,some detail, some nuance of location or colour to add. (14)

Those artisticimperativeswhich informGatsby'spartylose theirpower in a world dominatedby indiscriminate"seeing."More than miles separatethe chorus girl whose broken sobs smear her make-upinto musical notes and Myrtle's sister Catherine,of whose eyebrows Nick says: "[they] had been plucked and then drawnon again at a more rakish angle but the efforts of naturetoward the restorationof the old alignmentgave a blurredair to her face" (56, 34). In Gatsby's universe, a drivercan emerge from a crash not only unscathedbut oblivious to the fact thathe has shorna wheel off his car (58-60). At Myrtle'sparty,wherethe conditionsof naturecan be blurredbut never overcome, her very real blood will leave lasting stains on unmistakable furniture. Embeddedin a fiercely materialcondition, Myrtle has no reason to believe in "theunrealityof reality,[the] promisethatthe rock of the world [is] founded securely on a fairy's wing" (105). Like Nick, she knows that "you can't repeat the past" and recognizes more clearly than anythingelse that "youcan't live forever"(116, 40). Unableto makea grailof herunmysterious lover, Myrtle is like Gatsbybefore he falls for Daisy, wantingno more than to "takewhathe could andgo" (156). Because she cannotimagine changing

the world in which she lives, Myrtle longs only to escape it for a better one.

in escape as such.The young JamesGatz By contrast,Gatsbyis uninterested to he's no list of got get; in its place, he sketchesinto his copy of things keeps Hopalong Cassidy a schedule for self-transformation.

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration in Gatsby Elegiac MakingGatsbyHappen:The Toneof a Narrator'sVoice

223

Yet Gatsby is only partiallyresponsiblefor filling out his Platonic conception of himself. The well-wroughtcreationof Nick's visionary longing, Gatsby is as much a man-madeself as a self-made man. In orderto become the "somethinggorgeous"the prefacepromises,Gatsbyneeds Nick to fill in series of successful gesthe gaps and overlook the failuresin his "unbroken tures."ForGatsbyto happen,Nick mustwritea greenhousearoundhis hero's delicate greatnessand persuadeboth us and himself to believe in it. The obstacles Nick must surmountin order to accomplish our sense of Gatsby's gorgeousness become clearest at those moments when he fails to do so. We become sharplyawareof the resistanceovercome by Nick's most impressive act of cable-cutting-his renderingof the strangemagnificence of Gatsby'sparty-when gravityreassertsitself so forcefullyin Daisy's presence: There werethesamepeople..,.thesamemany-colored, manybutI felt an unpleasantness in the air,a keyedcommotion, thathadn'tbeen therebefore.Or perharshness pervading to accept WestEgg usedto it, grown grown hapsI hadmerely andits in itself,withits own standards as a worldcomplete it now I was at and owngreat again, through looking figures... Daisy'seyes. (110) By focusing our attentionon the incompletenessof Gatsby'sworld, Daisy's on which its radiance perspectivereveals the limitationsof those standards depends-the fragility of that environmentin which this hero can happen. Daisy's presence at Gatsby'spartyexposes how ephemeralis that greatness he shares with the protagonistof Tenderis the Night: "[T]o be included in Dick Diver's world for a while was a remarkable experience .... So long as [people] subscribedto it completely,theirhappinesswas his preoccupation, but at the first flicker of doubt as to its all-inclusivenesshe evaporatedbefore their eyes" (36). Looking back, one can see more clearly the effect of Nick's narration the "many-keyedcomearlierin the novel, the partit plays in transforming into "somethingsignificant,elementaland motion"of Gatsby'sextravaganza In the events which close Gatsby's first party profound"(51). themselves, are horrible;yet, when translatedthroughthe tissue of Nick's perception,

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

224

they come across very differently: I lookedaround. Mostof theremaining women werenow withmensaidtobetheir husbands. Even Jordan's having fights thequartet fromEastEgg,wererentasunder party, by dissension Thereluctance to go homewasnotconfined to wayward men.Thehallwasatpresent two sooccupied by deplorably bermenandtheirhighlyindignant wives Inspiteof thewives'agreement that[their mahusbands'] levolence wasbeyond thedispute endedin a short credibility andbothwiveswereliftedkicking intothenight. (56struggle 57) From an incongruous combination of modifiers (e.g., "deplorablysober men"),Nick's descriptionrings througha scale of strikinglydiscordantlinguistic registers:the elevationof "malevolence beyondcredibility"abuts thejournalisticstraightforwardness of "thedisputeendedin a shortstruggle" and finally sublimatesoff as the mock-lyrical"liftedkicking into the night." The facts themselvesarebrutal;only by ironizingtheminto playful inconsequence can Nick write a scene of couples fighting into a properfinale to Gatsby's party.In anothersense, there are no facts; wrappedround in the dense weave of his narrative behindNick's voice, peopleandthingsdisappear

telling of them.14

The same voice is almost silent when Daisy visits Gatsby'sparty.Like a role is reporter tryingsimply to keep trackof whathe sees, Nick's narratorial to As limited little more thantranscribing directlyquoteddialogue. a result, Nick's power to inflect the events he presentsis sharplyrestricted. A transnarrator Nick does little to distract us from parent innocently bystanding, seeing that there's nothing funny in Daisy's offering Tom her "little gold pencil" to take down the addressof anotherwoman;the "genial"tone Nick hearsin Daisy's voice is not his wry irony but her cutting sarcasm(112). At the same time, Daisy's cynical acceptanceof Tom's flirtationadds an ugliness to his adulterythatis less immediatewhen we see him alone with either Myrtle or Daisy. "I'd enjoyed these same people only two weeks before," Nick tells us. "But what had amusedme then turnedseptic on the air now" lends no redeemingsparkleto the only exchange we're (112). The narrative

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration inGatsby Elegiac

given between the party regulars: "Anything I hate is to get my head stuck in a pool," mumbledMiss Baedeker. "Theyalmostdrownedme once over in New Jersey." "Thenyou oughtto leave it alone,"countered DoctorCivet. criedMiss Baedekerviolently."Your "Speakforyourself!" hand shakes. I wouldn't let you operateon me!" (113)

225

Though only talk, the dialogue in this scene suggests that having your head

stuck in a pool could get you drowned,that the hilariousdrunkennessof a doctor might matterin those operatingrooms the talk makes real-in that worldwhich lies beyondthe edge of Gatsby'sperfectlawn,thatoutsiderealm whose presenceproves the incompletenessof Nick's fantasticone.

How They TurnOut at the End: DeathsPhysicaland Metaphorical

The airof menacewhich hangsover Daisy's visit precipitatesviolently in the scene of the car crash.Having escaped from the rooms in which she has been locked up by her husband,Myrtle runs out into the road, screaming back at George:

"Beat me!" [Michaelis] heard [Myrtle] cry. "Throwme down and beat me, you dirtylittle coward!" A momentlater she rushedout into the dusk, waving her hands and shouting;before he could move from his door the business was over. The "deathcar,"as the newspaperscalled it, didn'tstop;it came out of the gatheringdarkness,waveredtragicallyfor a aroundthe next bend .... The momentand then disappeared other car . . . came to rest a hundredyards beyond, and its back to whereMyrtleWilson, her life violently driverhurried extinguished, knelt in the road and mingled her thick, dark blood with the dust. Michaelis and this man reached her first but when they had tornopen her shirtwaiststill dampwith perspiration they saw that her left breast was swinging loose like a flap and there was no need to listen for the heartbeneath.The mouth

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

226

J N

was wide openandripped at the corners as thoughshe had chokeda littlein givingup the tremendous vitalityshe had stored so long.(144-45) As the narrativeveers away from Myrtle to Michaelis's view of her, the crashbecomes "thebusiness"and the momentof impactis hiddenby a shift to the newspaper'seven moredistantperspective.When we next see Myrtle, it's not immediatelyclear what happenedduringthe car's tragic wavering; the agency suggestedby Myrtle'skneelingandminglingalmostoverwhelms our sense of her devastation-a fact which has been relegatedto a phrase tangentialto the line of force drawnfrom the subject to its predicate("its driverhurriedback to where MyrtleWilson, her life violentlyextinguished, knelt in the road and mingled her thick, darkblood with the dust"). If left at all confused, however, we are quickly set straightby the next Fromthe mechanicalimage of Myrtle's brutallydirectstatement. paragraph's breast"swingingloose like a flap,"Michaelis's sweep of vision bringsus to "theheart"and "[t]hemouth":impersonalpartsthathave nothingto do with the woman until now defined by the sensuality with which she carriedher "surplusflesh" (29). Only a slammingcarcould tearaway thatbodily life no dreamcould sustain,and once Myrtleis dead, thereis absolutelynothingof her left. If Myrtleafterthe crashhas little in commonwithMyrtlebeforeit, Gatsby in this sense, Myrtle'sis the only physical is barely changedby his murder; death in the novel. The "colossal vitality of his illusion"is inseparablefrom Gatsby's own vitality; the momenthis dreamproves impossible is the mohas nothing ment of his own extinction(101). Gatsby'sdeathas a character the out of the Wilson he fades with to do story long trigger George pulls; executionercan accomplishhis misguidedjustice. before his redundant Sticks and Stones: Mundane Speech and Body Heat The day of Gatsby'sdoom is the kind when trainticketsreturnstainedby the sweat of the conductor'shand,when convertibles'seats leave theirdrivers wishing they'd parkedin the shade,when even the butlerglistens slightly. Througha noon like a teakettleboiling-"only the hot whistles of the National Biscuit Companybrokethe simmeringhush"(120)-Nick returnsto the scene of his history'sbeginningandentersthe Buchanans'living room to

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration in Gatsby Elegiac

discover that everythinghas changed:

227

one chapter

Theonlycompletely stationary objectin theroomwasan enormous couchonwhichtwoyoungwomen werebuoyed up as though balloon. uponananchored Theywerebothin white andtheirdresseswererippling andfluttering as if theyhad thehouse. justbeenblownbackin aftera short flightaround (12) chapter seven couch,likesilver DaisyandJordan layuponanenormous ownwhitedresses downtheir thesingidols,weighing against of the breeze fan. ing "Wecan'tmove," (122) theysaidtogether. The words Daisy didn't mean at all when she welcomed Nick in the first chapter-" 'I'm p-paralyzedwith happiness' "-are here corroborated by has moved thatmuchcloser to fact; the narrative's description(13). Flirt-talk metaphorhas deflatedand fallen backto earth;the women who once floated throughthe room like balloonsarenow silverballastunmovedby the breeze. At the same time, speech, which began the novel as the ephemeralfluff behindwhich the Real was obscured,has now gained an almostbodily presence: " 'The thing to do is to forgetaboutthe heat,'" says Tom." 'Youmake it ten times worse by crabbingaboutit' "(133). Overwhelmedby the materialityof her immediateenvironment-what Italo Calvino calls "theweight, the inertia, the opacity of the world" (4)-Daisy's voice "struggle[s] on throughthe heat, beating against it, moulding its senselessness into forms" (125). The temperature weighs heavily on that cable-cuttingbanterwhich might otherwise have relieved the scene's oppressive mood: " 'It's so hot,' [Daisy] complained.'Yougo. We'll ride aroundandmeet you after.'With an effort her wit rose faintly, 'We'll meet you on some corner.I'll be the man smokingtwo cigarettes'"(132). In air so thick that"everyextragesturewas an affrontto the common storeof life," not even the thrill of Daisy's casual fiction can raise conversationabove that sensuous experience Nick recalls

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

228

most vividly, the "sharp kept climbphysical memorythat..,. my underwear of beads sweat raced ing like a damp snake aroundmy legs and intermittent cool across my back"(121, 132-33). No longerable to lift its audienceaway from the bodies of the novel's characters,language now clings tightly to them. Wanting"nothingless of Daisy than that she should go to her husband and say, 'I never loved you,' " Gatsby arrangesa confrontationwith Tom designed to set the stage for his returnwith Daisy to the life they left five yearsearlier(116). But Daisy refusesto play the role Gatsbyhas scriptedfor her, and our hero proves unable to "'fix everythingjust the way it was before'" (117). Unwilling to say that she never loved her husband,to "[wipe] out" the three years of their marriage,Daisy leaves Gatsby facing Tom's insistencethat" 'there'rethingsbetweenDaisy andme thatyou'll triumphant never know, things that neitherof us can ever forget'" (139, 140). Against these "things"-the irrevocable historyof a honeymoonin a particular place, no his fantastic ambitions has the fact of a real daughter-Gatsby defense; have run agroundon the rock of the world. For Nick's hero, this is the motells us, "seemed mentof the car'simpact: Tom'sunrefuted claims,thenarrator " and later we learn that to bite physically into Gatsby," 'Jay Gatsby' had brokenup like glass againstTom'shardmalice"(140, 155). "JayGatsby"the perfect achievementof James Gatz's carefully scheduledmetamorphosis-exists no longer; the man who filled the contoursof the name he invented for himself has been translatedby Tom into "Mr.Nobody from Nowhere"(137). The destructionof his defining dreamnearlycomplete,thereis not much more of Gatsby'sstoryleft to tell. Fromhis first sight of an indistinctneighbor with arms stretchedtowarda distantgreen light, Nick has been brought to a vision of Gatsbywaitingon Daisy's lawn to makesureshe'll be all right, the "sacrednessof [his] vigil" reducedto a "watchingover nothing"(153). Nick's descriptionof Gatsby'sdeathfeels almost like an epilogue: of the water movement Therewasa faint,barely perceptible thedrain its waytoward as thefreshflow fromoneendurged theshadows of With littleripples thatwerehardly attheother. downthepool.A moved waves,theladenmattress irregularly the surface was smallgustof windthatscarcely corrugated with its accidental burcourse disturb its accidental to enough of leavesrevolved it slowly,tracden.Thetouchof a cluster

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration in Gatsby Elegiac

a thinredcirclein thewater. ing, liketheleg of a compass, It wasafterwe started withGatsby toward thehousethat the gardener sawWilson's bodya littlewayoff in the grass, andtheholocaust wascomplete. (97, 170)

229

In a world where motion and matterhave been reducedto an absoluteminimum andactionhas been emptiedof intent,thereis no mentionof the corpse Nick has discovered.The mass that warps the mattresslacks the weight to keep its course against the most qualified of currents(so scarce it hardly shadowswaves); in the absenceof all desire,this ghostly bier spins slowly at the touch of leaves. As its hero fades and the novel's exhaustedplot winds down, the history of Nick's attemptto authora purely creative work rises to a climax. In his accountof Gatsby'slast moments,Nick's narrative leaves behindthe matterof-fact and entersentirelyinto the metaphorical: where Myrtle'sviolent destructionleaves behinda thingout of which herpersonalityhas been brutally ripped, all that remains of the man that was Gatsby is a red circle drawn acrosstroubledwater.What'sleft of Gatsbythe hero transcends not only the fact of his body but the limitationsof physical law altogether:in the real world, the shot that killed a man floating on an air mattresswould likely puncturethe raftand leave him lying at the bottomof the pool. By his cablecuttingaccountof Gatsby'sdeath,Nick sets him spinningimpossiblythrough a world disengagedfrom what we know of how things work-into the only world in which even Gatsbycould happenand turnout all right at the end.

CornellUniversity Ithaca,New York

Notes

1. 2. James 33-34; Fitzgerald,Life 67. In this respect,Nick experienceswhatMikhailBakhtindescribesas a "fulldialogization of consciousness"in which "[t]heother'sdiscourse..,. penetrates the consciousness and in monologically confispeech of the hero"in forms which "wouldnot be appropriate dent speech"(222). In so doing, Nick designs a narrative like one of Kermode's"end-determined fictions": "Men,like poets, rush 'into the middest,'in media res, when they areborn;they also die

3.

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

230

in mediis rebus,and to make sense of theirspanthey need fictive concordswith origins and ends, such as give meaningto lives and to poems"(6, 7). 4. This parentheticalspace within which speakersask their listeners to visualize a nonexistent comparison(as Nick asks us to imagine a woman balancing an object on her chin) might function like the "asides"in a play. Both rhetoricalforms create a space outside the ordinarychannelsof communicationfrom which characters can speak more to their audiences. directly Nick's surrounding descriptionmight reinforceour sense of the rightnessof this "world elsewhere":"Twentymiles from the city a pair of enormouseggs, identical in contour and separatedonly by a courtesy bay, jut out into the most domesticatedbody of salt waterin the WesternHemisphere,the greatwet barnyard of Long IslandSound"(9). By inlets and chickens laying eggs for farmhinting at a likeness between "domesticated" ers, Nick's unusualchoice of words might suggest that both these naturalbodies are redefinedby the "courtesy" they show towardhumanbeings. To Harvey'sacuteanalysisof how these two images createa "doubleexposure,"I would add thatthe apparently onomatopoeicdescriptionof Tom closing the windows-"Then there was a boom as Tom Buchananshut the rear windows"-serves not only as the sound of the windows slamming, but as a ship's "boom"as well, therebyclosing the collocation of metaphors(95). Thereareothermomentsin Gatsbywhen Fitzgeraldcreates a context that brings out the homonymicpotentialof words; see, for example, the descriptionwhich distinguishesMyrtle from the ashes that surroundher: "She smiled slowly and walking throughher husbandas if he were a ghost shook hands with Tom, looking himflush in the eye. Then she wet her lips" (my emphasis,30). "Forexample," Cartercontinues," 'busy' [and] 'buzz' have a high probabilityof cowith 'bee';bee in turnregularly co-occurswithwordssuchas 'hive' or 'honey' occurrence and less regularlywith items such as 'intrepid'or 'transmogrifying' "(159). sentencesthroughwhich the It's worth noticing the resemblancebetween the paratactic ashes transmutethemselves into people and those syntactic hurdles over which the Buchanans'lawn must leap in its race towardtheirhouse: The lawn startedat the beach and ran toward the front door for a quarterof a mile, jumpingover sun-dialsand brickwalks and burning gardens-finally, when it reachedthe house driftingup the side in brightvines as thoughfrom the momentumof its run.(11)

*c *c *

5.

6.

7.

8.

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration inGatsby Elegiac

where ashes takethe formsof houses andchimneysandrising smoke and finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and alreadycrumblingthroughthe powdery air.

231

The parallelsentence shapes sharedby these animateterrainsmight suggest an unlikely consonance between East Egg and the Valley of Ashes. In the basic insinceritybehind Daisy's thrilling smiles, the dimly rememberedscandal associated with Jordan'ssardonic charm, and the cruelty implicit in Tom's lever-like body, there might be ashes already.Withinworlds moreor less explicitly burntout, wherepeople lack those dreaming ambitions which could give form to their restlessness, agency diffuses into landscapes which run and leap and shape themselves. 9. The same images of opulence with which Myrtlecan only cover her furniture,serve as the models by which Gatsbybuilds his dreaminto concrete being; her ungainly aspirations to "scenes . . . of Versailles"are his actual "MarieAntoinette music rooms and Restorationsalons"(96).

10. As Podis puts it: "The vehicle used to metaphorizeMyrtle... comes with no definite presuppositionsattachedto it, since it has no priorexistence in language"(65). thatis "justpersonal,"Myrtleexpresses 11. Drawnby materialambitionsinto a relationship she is rendered"fluent"only by the flow herself most articulatelyin "body-language"; on herside to obscurehertoo-sensualcontours,Myrtle of herblood. Withoutthe narrator lacks the means to tell a story in which she turnsout all rightat the end. Because she has visions for her,Myrtleproves finally as perishableas her no one to speakherunutterable flesh. 12. For a differentapproachto Fitzgerald'suse of this trope, see Hilton Anderson'sdiscussion of "Synecdochein The Great Gatsby."Basically,Andersonargues that Fitzgerald representsGatsby by his smile and Daisy by her voice in order to delay his readers' discovery of these characters'more distastefulqualities. 13. Preface to RoderickHudson (5). 14. Fitzgeraldrecognizes the power of this kind of obscurationin his explanationof the of Daisy's "tremendous fault"constituted by the novel'slackof"an emotionalpresentment lack of the attitudetowardGatsby after their reunion(and consequent logic or importance in her throwinghim over)":"Everyonehas felt this but no one has spotted it because its [sic] concealedbeneathelaborateandoverlappingblanketsof prose"(Letterto H. L. Mencken,Life 110).

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

232

Works Cited

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. Problems of Dostoevsky'sPoetics. Ed. and Trans.by Caryl Emerson. Minnesota:Universityof MinnesotaPress, 1984. A Reader Ed. Barthes,Roland. "TheReality Effect."Rpt. in FrenchLiteraryTheoryToday: Tzvetan Todorov.Trans.R. Carter. CambridgeUniversityPress, 1982. Carter,Ronald. "Sociolinguisticsand the Integrated English Lesson."In Linguisticsand the Teacher.Ed. RonaldCarter. Boston: Routledge, 1982. Fitzgerald,F. Scott.A Life in Letters.Ed. MatthewJ. Bruccoli.New York:CharlesScribner's Sons, 1994. . The Great Gatsby.New York:Macmillan, 1992. . Tenderis the Night. New York:Macmillan,1996. CenturyInterHarvey,W. J. "Themeand Texturein The Great Gatsby."Rept. in Twentieth pretations of The GreatGatsby.Ed. ErnestH. Lockridge.Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall,1968. Jakobson,Roman. "Closing Statement:Linguistics and Poetics." In Style in Language. Ed. ThomasA. Sebeok. New York:JohnWiley & Sons, 1960. James, Henry. "Preface."The American.Rpt. in The Art of the Novel. New York:Charles Scribner'sSons, 1934. "Preface." RoderickHudson.Rpt.in TheArtof theNovel. New York:CharlesScribner's . Sons, 1934. Kermode,Frank.TheSense of an Ending.New York:OxfordUniversityPress, 1966. Levin, Samuel R. MetaphoricWorlds: Conceptionsof a RomanticNature.New Haven:Yale University Press, 1988. InMetaphor and Thought, concepts,andworld:Threedomainsof metaphor." ."Language, 2nd edition. Ed. AndrewOrtony.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress, 1993. Long, Robert Emmet. "The Great Gatsby-The IntricateArt." Rpt. in Critical Essays on Fitzgerald'sThe GreatGatsby.Ed. Scott Donaldson. Boston: G. K. Hall & Company, 1984. as One Kindof SpeechAct."Meaning:A CommonGroundof Mack, Dorothy."Metaphoring and Literature. Ed. Don L. F. Nilsen. CedarFalls: University of Northern Linguistics Iowa Press, 1973.

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Narration in Gatsby Elegiac

233

Podis, LeonardA. " 'The Unrealityof Reality': Metaphorin The Great Gatsby."Style 11 (1977): 56-72. Poirier,Richard.A WorldElsewhere:The Place of Style in AmericanLiterature.New York: Oxford UniversityPress, 1966.

This content downloaded from 70.112.207.146 on Fri, 21 Feb 2014 01:42:05 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Berardi - The Soul at Work - From Alienation To AutonomyDocumento113 pagineBerardi - The Soul at Work - From Alienation To AutonomyPoly Styrene100% (5)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- 10 Stages To A Breakup (Relationships)Documento8 pagine10 Stages To A Breakup (Relationships)Bob CookNessuna valutazione finora

- Accelerationism Hyperstition and Myth-ScDocumento22 pagineAccelerationism Hyperstition and Myth-ScJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Realism and Naturalism in Nineteenth C AmericaDocumento249 pagineRealism and Naturalism in Nineteenth C America1pinkpanther99Nessuna valutazione finora

- Woman Hating - Andrea Dworkin PDFDocumento207 pagineWoman Hating - Andrea Dworkin PDFlamenzies123100% (7)

- A Day Without TechnologyDocumento6 pagineA Day Without TechnologyRenztot Yan EhNessuna valutazione finora

- Marxism and Roman Slavery PDFDocumento26 pagineMarxism and Roman Slavery PDFJacob Lundquist100% (1)

- AnalysisDocumento51 pagineAnalysisPrecylyn Garcia BuñaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Croix Marx Antiquity Article PDFDocumento36 pagineCroix Marx Antiquity Article PDFJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Toward The Spartan Revolution PDFDocumento27 pagineToward The Spartan Revolution PDFJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Ideology in The Iliad - Rose PDFDocumento49 pagineIdeology in The Iliad - Rose PDFJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Intro Marx and ClassicsDocumento3 pagineIntro Marx and ClassicsJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Greek Art and Lit in Marx PDFDocumento27 pagineGreek Art and Lit in Marx PDFJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Buck-Morss, S. - Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History PDFDocumento172 pagineBuck-Morss, S. - Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History PDFJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Animal-Attentive Queer Theories PDFDocumento138 pagineAnimal-Attentive Queer Theories PDFJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Classes and Society in Classical Greece PDFDocumento34 pagineClasses and Society in Classical Greece PDFJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Complianceisgendered1 PDFDocumento16 pagineComplianceisgendered1 PDFJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Franco Berardi The Uprising On Poetry and Finance 1 PDFDocumento87 pagineFranco Berardi The Uprising On Poetry and Finance 1 PDFJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- 44847251Documento19 pagine44847251Jacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- AnthropocentricmDocumento16 pagineAnthropocentricmdeary74Nessuna valutazione finora

- Berlant InfantileCitizenshipDocumento19 pagineBerlant InfantileCitizenshipJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- A Natural Choice D Ponton May 2015 FinalDocumento19 pagineA Natural Choice D Ponton May 2015 FinalJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Awakening at The Point of No ReturnDocumento4 pagineAwakening at The Point of No ReturnJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Email FlowchartDocumento1 paginaEmail FlowchartJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 PBDocumento20 pagine1 PBJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender-Related Difference in The Slave Narratives of Harriet Jacobs and Frederick DouglassDocumento22 pagineGender-Related Difference in The Slave Narratives of Harriet Jacobs and Frederick DouglassJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- EScholarship UC Item 8td2j5r5Documento59 pagineEScholarship UC Item 8td2j5r5Jacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Marriott Corpsing ReviewDocumento10 pagineMarriott Corpsing ReviewJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 PBDocumento21 pagine1 PBJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Gut Sociality Janus Head-LibreDocumento27 pagineGut Sociality Janus Head-LibreJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Freccero Mirrors of CultureDocumento10 pagineFreccero Mirrors of CultureJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Ableism K Complete UNT 2012Documento143 pagineAbleism K Complete UNT 2012Colin BascoNessuna valutazione finora

- Global Warming Bad - JDI 2013Documento25 pagineGlobal Warming Bad - JDI 2013David DempseyNessuna valutazione finora

- Chase Anna C 201106 PHD ThesisDocumento227 pagineChase Anna C 201106 PHD ThesisJacob LundquistNessuna valutazione finora

- Literary AnalysisDocumento5 pagineLiterary Analysisapi-358270712Nessuna valutazione finora

- Drama: Drama Is A Literary Composition Involving ConflictDocumento6 pagineDrama: Drama Is A Literary Composition Involving ConflictElvin Nobleza PalaoNessuna valutazione finora

- International Man Booker PrizeDocumento8 pagineInternational Man Booker PrizeThavam RatnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Early Life: The European MagazineDocumento5 pagineEarly Life: The European MagazineSanyam JainNessuna valutazione finora

- Royal Road v13Documento126 pagineRoyal Road v13kresnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Enotes - The Eve of ST Agnes Part 1 (Learn) PDF Keats, JohnDocumento2 pagineEnotes - The Eve of ST Agnes Part 1 (Learn) PDF Keats, Johnlanzarote777Nessuna valutazione finora

- Romanticism and ByronDocumento3 pagineRomanticism and ByronPaulescu Daniela AnetaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 of Cups Upright Love - Google SearchDocumento1 pagina2 of Cups Upright Love - Google SearchNoel Angelo MacawayNessuna valutazione finora

- 02 Evolution of Western LiteratureDocumento9 pagine02 Evolution of Western LiteratureFrancis SoriaNessuna valutazione finora

- Biag Ni Lam-AngDocumento17 pagineBiag Ni Lam-AngLuke Matthew De LeonNessuna valutazione finora

- Franz GrillparzerDocumento9 pagineFranz GrillparzerDiana GhiusNessuna valutazione finora

- The Scarlet Letter: Identity Theme inDocumento2 pagineThe Scarlet Letter: Identity Theme inIoana MunteanuNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature: Genres of LiteratureDocumento5 pagineLiterature: Genres of LiteratureBianca Jane AsuncionNessuna valutazione finora

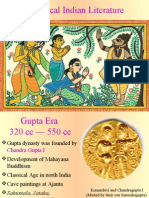

- Classical Indian LiteratureDocumento19 pagineClassical Indian LiteratureAnand Choudhary100% (1)

- Figure and Affect in CollinsDocumento21 pagineFigure and Affect in CollinsShih-hongChuangNessuna valutazione finora

- Jane Nissen Books Catalogue 2013Documento1 paginaJane Nissen Books Catalogue 2013Pip JohnsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Drama As A Dominant Form in The Elizabethan AgeDocumento9 pagineDrama As A Dominant Form in The Elizabethan AgeTaibur Rahaman100% (1)

- Farrell Privacy in Miller's TaleDocumento24 pagineFarrell Privacy in Miller's TalediscoveringmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Act 2 Scene 2Documento3 pagineAct 2 Scene 2folaloveNessuna valutazione finora

- R&W Narrative ReportDocumento5 pagineR&W Narrative ReportElaine SarabiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ser and Estar ExplanationDocumento3 pagineSer and Estar ExplanationCarlos VillegasNessuna valutazione finora

- Dead Poet SocietyDocumento2 pagineDead Poet SocietyRensun LaureñoNessuna valutazione finora

- Beauty and The Beast and Social DynamicsDocumento9 pagineBeauty and The Beast and Social DynamicsEric ChienNessuna valutazione finora

- Written by BhavyaDocumento2 pagineWritten by Bhavyasales zfNessuna valutazione finora

- 5th Adol Mid-TermDocumento3 pagine5th Adol Mid-TermwelcomevtNessuna valutazione finora

- Mandrie Si PrejudecataDocumento2 pagineMandrie Si PrejudecataIoana Cristea50% (2)