Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Brands As Ideological - The Cola Wars

Caricato da

mgolaghaeeTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Brands As Ideological - The Cola Wars

Caricato da

mgolaghaeeCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Journal of Business Case Studies March/April 2009

Volume 5, Number 2

Brands As Ideological Symbols: The Cola Wars

Praveen Aggarwal, University of Minnesota Duluth, USA Kjell Knudsen, University of Minnesota Duluth, USA Ahmed Maamoun, University of Minnesota Duluth, USA

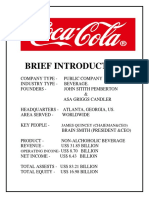

ABSTRACT The Coca-Cola Company is the undisputed global leader in the cola industry. Despite its size and marketing savvy, the company has faced a barrage of competition from new companies in the Middle East and some parts of Europe. These companies have tried to create a niche for themselves by tapping into the anti-U.S. sentiment that prevails among a section of population in these markets. We review three such competitors, Zam Zam Cola, Mecca Cola, and Qibla Cola and their strategies for challenging the global giant. Keywords: Cola Wars, Anti-U.S. sentiment, Beverages industry. THE COCA-COLA COMPANY

ith sales and operations in over 200 countries, The Coca-Cola Company is the worlds largest producer and marketer of nonalcoholic beverage concentrates in the world. While Coca-Cola beverages have been sold in the United States since 1886, the company has made significant advances in its global reach and dominance in the last few decades. Of the roughly 50 billion beverage servings consumed worldwide on any given day. The Coca-Cola Company serves 1.3 billion of those servings. In terms of worldwide sales of nonalcoholic beverages, the company claimed a 10% market share in 2004, while employing approximately 50,000 people. As of 2004, the company divided its global operations into six segments or operating groups: North America Africa Asia Europe, Eurasia and Middle East Latin America Corporate The relative size and contributions of these segments are given in Table 1. The Coca-Cola Company recognizes a number of factors that could create challenges and risks for the company. Specifically, it identifies peoples obesity concerns, water quality and availability issues, changing consumer preferences, and increasing competition as potential threats. In the Middle Eastern market, an important element that contributes to changing consumer preferences and increased competition is the political environment in which the company operates. Since 2000, the turmoil in the Middle East the second Palestinian Intifada and the second Gulf War has created an anti-American sentiment that has not only given rise to new competitors in the Middle East, but has also fueled consumer resentment against American brands. Both established companies and entrepreneurs have taken advantage of the anti-American climate in the Middle East and even Europe to market products that taste and look like the real thing.

27

Journal of Business Case Studies March/April 2009

Volume 5, Number 2

Table 1: The Coco-Cola Company Performance Overview: 2004 ($ million) Europe, North Eurasia and Latin America Africa Asia Middle East America Corporate Net Operating Revenue 2004 $6,643 $1,067 $4,691 $7,195 $2,123 $243 2003 6,344 827 5,052 6,556 2,042 223 2002 6,264 684 5,054 5,262 2,089 211 Operating income 2004 $1,606 $340 $1,758 $1,898 $1,069 ($973) 2003 1,282 249 1,690 1,908 970 -878 2002 1,531 224 1,820 1,612 1,033 -762 Income before taxes 2004 $1,629 $337 $1,841 $1,916 $1,270 ($771) 2003 1,326 249 1,740 1,921 975 -716 2002 1,552 187 1,848 1,540 1,081 -709 Source: The Coca-Cola Company Annual Report 2004

Consolidated $21,962 21,044 19,564 $5,698 5,221 5,458 $6,222 5,495 5,499

The five geographic segments are quite different in their market structures as well as consumption habits. The Coca-Cola Company reports the following information pertaining to these segments (Table 2):

Table 2: Market Characteristics of the Segments Company Employees (Includes Corporate) 11,700 8,400 9,400 16,200 4,700 Annual Per Capita Consumption of Company Products 411 servings 35 servings 26 servings 82 servings 214 servings

Population 333 million North America 869 million Africa 3.3 billion Asia Europe, Eurasia, 1.2 billion and Middle East 547 million Latin America Source: The Coca-Cola Company Annual Report 2004

Brands Sold 93 86 184 129 105

The trend can be traced back to late 2000 when the then Israeli opposition leader, Ariel Sharon, visited the religious compound in Jerusalem to assert that the site would remain under Israeli sovereignty if his party won the election. The compound is the holiest site in Judaism (Temple Mount) and the third holiest site in Islam (Al-Aqsa Mosque). Although Sharon did not actually go into Al-Aqsa Mosque, the visit ignited the second Palestinian uprising, also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada. Violence, riots, and unrest erupted in Jerusalem, and almost instantly spread to other Palestinian territories. Throughout the Middle East, people were manifesting an unprecedented solidarity with the Palestinian cause through gigantic demonstrations chanting anti-Israeli and anti-American slogans. American MNCs were caught in the backlash as street anger turned into calls to boycott American brands, including McDonald's, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, KFC, Pizza Hut, Marlboro, Proctor & Gamble, and Starbucks. Capitalizing on the boycott campaign, a range of "Muslim-friendly" drinks was launched as part of a backlash against U.S. brands such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi. Three such brands, Zam Zam Cola, Mecca-Cola, and Qibla Cola, managed to ride the anti-American sentiments and boost their sales. Though they had different histories - Mecca and Qibla were founded in Europe in 2002 and 2003 respectively by Muslim entrepreneurs, while Zam Zam is a product of the Iranian Revolution - their strategies were similar. Each brand attempted to get the most out of the antiAmerican sentiment among Muslim consumers. Table 3 provides a break-up of Coca-Colas 2004 unit case volume for the segment Europe, Eurasia, and Middle East.

28

Journal of Business Case Studies March/April 2009

Table 3: Europe, Eurasia, & Middle East: 2004 Unit Case Volume Country/Region Share Germany 14% Eurasia and Middle East 12% UK 12% Spain 12% Central Europe and Russia 11% France 7% Italy 6% Belgium 3% Netherland 3% Other 20% Source: The Coca-Cola Company Annual Report 2004

Volume 5, Number 2

ZAM ZAM COLA Zam Zam Cola, named after the Well of Zamzam in Mecca that Muslims consider sacred, was founded in 1954 as the Iranian partner of Pepsi until their contract was terminated after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Zam Zam's 17 plants bottled Pepsi between 1954 and 1979, when American companies assets were confiscated in t he aftermath of the Ayatollah coup. Since then, the company has been controlled by the Foundation of the Dispossessed, a powerful state charity run by clerics. For nearly half a century, Zam Zam's main market remained the home market of Iran. Zam Zam Cola has long been a local player with its 65 products distributed throughout Iran (Zam Zam Group Web site). The turning point was the turmoil in the Palestinian territories which reached its peak in spring 2002. Consumers in the Muslim world stepped up boycotts of American products to protest support of Israel in the ongoing Middle East conflict. As a result, Zam Zam Cola was bombarded by substantial orders from neighboring Arab countries. The company took advantage of the opportunity, and Iranian factories worked round the clock to pick up the slack. Within four months, the company captured a sizable Middle Eastern market, and exported millions of cans to Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states (Arabic News 2002). "The campaign of boycotting American products and the good quality of Zamzam Cola have given us excellent sales," general manager Firas Khawaja told Reuters news agency (BBC News 2002). In fact, the company didnt really venture overseas and register its trademark with the World Intellectual Property Organization until December 2002 (World Intellectual Property Organization 2002). By the end of 2002, Saudi Arabia unofficially named Zam Zam the "Hajj drink". Ten million bottles of Zam Zam were exported to Saudi Arabia and Gulf countries during the pilgrima ge season to Mecca. After Arab countries in the region started boycotting some American goods, including Coca-Cola, demand for Zam Zam really took off, Bahram Kheiry, Zam Zams marketing manager said in October 2002 (Theodoulou, et al 2002). Zam Zams cola was exported to Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Kuwait, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. After capturing a sizeable share in the Middle Eastern market, Zam Zam turned to Europe, and Denmark was its first stop (Copenhagen Post Online 2002). By early 2003, U.S. companies in the Middle East were hoping to recover from the two plus year boycott campaign. However, the war in Iraq did not help. Operation Iraqi Freedom gave consumers in the Middle East one more reason to continue boycotting American MNCs. Just as the boycott campaign, initially inspired by the Palestinian intifada was starting to loose steam, the war in Iraq gave it energy and force. Many Arabs were furious over Iraqi civilian casualties, the excessive force used in bombarding Baghdad, and mistrust over the actual reasons for the invasion (Gulf News 2003). This renewed interest in the boycott was good news for Zam Zam which announced plans to upgrade and expand production plants in Iran to meet the growing demand for its drinks. The company also announced the setting up of additional bottling facilities in neighboring Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Dubai (Middle East Times 2002). In July 2003, Zam Zam was in the process of establishing a factory in Bahrain or the United Arab Emirates to 29

Journal of Business Case Studies March/April 2009

Volume 5, Number 2

avoid tariffs and reduce transport costs. The six Gulf Arab countries of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, and Oman constitute a free trade area (Arabic News 2002). However, in a sudden and unexpected move, the authorities in Saudi Arabia banned Zam Zam imports as there were objections over its brand name (AME Info 2003). The local distributor, Al-Majarra Company, was in disbelief. We have not received any official communiqu from the Ministry of Comme rce and Industry or from Saudi customs about the issue, a company spokesman told Arab News (Haider & Al-Harbi 2003). The ban came as a relief to Coke and Pepsi after an 18-month boycott. Things have improved for Coca-Cola and Pepsi and people are gradually returning to them. The boycott is dying down . Zamzam Cola is the only drink which had the potential to make a dent into the market of these two American soft drink companies. Its name was the biggest attraction, a major supermarket chain staff said in an interview (Haider 2003). MECCA COLA Capitalizing on the same anti-American sentiment, Tawfiq Mathlouthi, a French Muslim entrepreneur who emigrated from his native Tunisia in 1977, launched Mecca-Cola in Paris in November 2002. It all began when Mr. Mathlouthi asked his ten-year old son to give up drinking Coke because of its American origin. His son agreed, but only if Mr. Mathlouthi could provide an alternative. That's how the idea was born,'' Mathlouthi said in an interview (Tagliabue 2002). His objective was to cater to European Arabs and Muslims who boycotted the U.S. beverages. He argued that his product would give consumers a soft drink choice that did not implicitly offer support to American policies in the region. Mr. Mathlouthi even pro mised that 10% of the profits would go to a Palestinian childrens charity and another 10% to support charitable associations in the country where product was sold . The launch was relatively successful and Mecca sold more than 2 million of its 1.5-litre bottles in France within two months, each one described by the company's founder as "a little gesture against US imperialism and foreign policy". Mr. Mathlouthi also added that "demand has been phenomenal" (Henley & Vasagar 2003). Mathlouthi, a lawyer and journalist who ran a radio station for France's Muslim minority, has been known for his strong opposition to the American and Israeli policies. He has publicly issued declarations against "Imperialism and Zionism" from time to time. It is all about combating "America's imperialism and Zionism by providing a substitute for American goods and increasing the blockade of countries boycotting American goods," Mr. Mathlouthi told BBC News Online (Murphy 2003). In another statement, he explained: "People are thirsty for a way to stand up to American hypocrisy . Mecca Cola is not just a drink It is an act of protest against Bush and Rumsfeld and their policies" (Delves 2003). The prominently visible slogan, "Ne buvez plus idiot, buvez engag" or Don't drink stupid, drink with commitment clearly explained the attitude of the company. The product label may look like Coca-Cola's, but the message was undoubtedly controversial and probably provocative. The brand name itself referred to Mecca, the holiest city of Islam located in Saudi Arabia. The label also mentions: "Please do not mix with alcohol." Coca-Cola dismissed Mr. Mathlouthi's move, saying he had "identified a commercial opportunity which involves the exploitation in Europe of the difficult and complex si tuation in the Middle East Ultimately it is the consumer who will make the decision," the company said in a statement (Murphy 2003). The consumer made the decision and Cokes sales dropped, forcing Coca - Cola executives to distance themselves from U.S. Middle East policy. A spokesman said: We are a business, so we do not get involved in political issues (Theodoulou, et al 2002). Nevertheless, in December 2002, Coke acknowledged that the Arab boycott had wounded the company. The president of Coca-Cola Africa, Alexander B. Cummings Jr., told analysts that ''our business in these countries has been hurt by the boycotting of American brands.'' Another Coke executive, asked about Mecca-Cola, replied briefly, ''We are aware of Mecca, and we have felt the impact of the boycott of American goods'' (Tagliabue 2002). Mathlouthi's Mecca Cola has been a huge success since the start of sales in early November 2002. From his warehouse in Paris he shipped out over a million bottles per week to local supermarkets and grocery stores. He 30

Journal of Business Case Studies March/April 2009

Volume 5, Number 2

didnt spend on advertising, but rather relied on word of mouth, creating a buzz, and featuring Palestinian children fighting Israeli soldiers on the companys Web site. Mathlouthi's marketing strategy was that real-life footage of the Intifada would be more effective and obviously less expensive than hiring celebrities to endorse his product. Palestinian donations were a major selling point as well (Kovach 2002). Meanwhile, Mathlouthi admitted that an imminent war in the Middle East would soar his sales. The biggest boost for Mecca-Cola would be war in Iraq. If there's a war, you'd have an extraordinary flare-up of MeccaCola'' (Theodoulou, et al 2002). Mathlouthi was right. Sales surged as other supporters joined forces after the U.S. war in Iraq. Orders from Arab and European countries started to pour in on the company, together with bids from companies wanting to become local distributors. Riding on anti-American anger over issues like Palestine, Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan, Mecca Cola achieved impressive sales in a very short period of time. For example, in January 2003, Mecca opened its UK base in Birmingham and sold 300,000 liters in two weeks (Grimston 2003). In May 2003, Mecca was introduced in Yemen and was distributed through a sole agent (Yemen Times 2003a). Mr. Mathlouthi held a press conference in Sanaa, Yemen, in December 2003 and announced that the company would build a factory for Mecca-Cola in Sanaa by mid 2004 (Yemen Times 2003b). In August 2003, Mecca moved its headquarters to Dubai and announced plans to invest Dh35 million (approximately $10 million) in a facility in Jebel Ali Free Zone to produce the new Muslim alternative to the existing colas in the market. The new plant was expected to manufacture almost 400,000 cans per day, and was expected to be operational by the end of 2004 (Qadir 2003). In June 2004, Mecca Cola went on sale in parts of Israel for the first time. Bottles featuring illustrations of Jerusalem's landmark Dome of the Rock lined the shelves in Arab Israeli towns and markets. "Drink from commitment, taste the flavor of freedom," was written in Arabic on the bottle. Mr. Mathlouthi said that he wanted to "struggle against Zionism inside its home" (Ettinger 2004). He also added that he got the idea to launch Mecca during Israel's siege of the Palestinian city of Jenin during the second Intifada. In late 2004, in order to win back customers, Coca-Cola aired a stunning commercial across the Middle East featuring Arab pop star Nancy Ajram. According to Cokes regional manager, the pricey ad had an immediate impact across the Arab region (Los Angeles Times 2008). QIBLA COLA Qibla was launched in the British market in February 2003, following the initial success of Mathlouthi's Mecca brand in France, targeting the 2.5 million Muslim community in the U.K. The two founders of the company were cousins, Zahida Parveen and Zafer Iqbal. Like its counterpart, it used a religious tag and a catchy slogan. Qibla is an Islamic term which means the direction in which all Muslims turn their faces in prayers and that direction is towards the Ka'abah (a square stone building in the Sacred Mosque) in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. "Liberate Your Taste" declared Qibla Colas slogan. The company announced that ten percent of p rofits from every two-liter bottle sold would go to the Muslim charity Islamic Aid, which specializes in establishing humanitarian projects in some of the world's most deprived communities. The company admitted its directors had no experience in the soft drink market, yet they saw an opportunity. By offering a dose of activism along with the usual sugar, preservatives and carbonated water, Parveen and Iqbal were utilizing the same strategy Zam Zam and Mecca adopted: cashing in on antiAmerican sentiment (BBC News 2003). Ms. Parveen said she designed the drink to provide an ethical alternative for Muslims. She said in an interview that Qibla Cola was asking consumers to liberate their taste buds from the multibillion dollar marketing machines. "By choosing to boycott major brands, consumers are sending a powerful signal: that the exploitation of Muslims cannot continue unchecked" (CBC News 2003). "Muslims are increasingly questioning the role some major multinationals play in our societies. They ask, should the money of the oppressed go to the oppressors?" she explained in another interview (Jeffery 2003). Qibla had a relatively good start and sold millions of units in the first few months by securing independent local retailers and restaurants. They also had ambitious and quick plans to take the brand global. In November 2003, Qibla products were introduced in the Norwegian market (The Qibla Cola Company 2003 ). In January 2004, Qibla 31

Journal of Business Case Studies March/April 2009

Volume 5, Number 2

signed an agreement with a distributor in Bangladesh to bottle locally and distribute products of the Qibla Cola Company. Commenting on the contract, Mohammed Haider, Chief Business Development Officer said, The appeal for Qibla Cola is gaining global momentum. Consumers appreciate the way Qibla Cola tastes and looks whilst knowing that their money will contribute to worthy causes, (The Qibla Cola Company 2004a). In March 2004, Qibla signed an agreement with Mighty Beverages Ltd of Pakistan to exclusively bottle and distribute products of the Qibla Cola Company in Pakistan (The Qibla Cola Company 2004b). In September 2004, Qibla announced on its Web site that the company was distributing its products in Canada, Netherlands, Norway and Pakistan with Australia, Libya and Malaysia to follow soon (The Qibla Cola Company 2004c). Regardless of this apparent progress and expansion, the company struggled to keep up its momentum. In July 2004, charity Islamic Aid cancelled its agreement with Qibla Cola because it had not yet received any money. When Qibla Cola was established in 2003, it marketed itself on the selling point that 10% of profits would go to charity. Qibla responded to the agreement cancellation by renewing its promise to donate to charity once it started making profits (BBC News 2004). As the year 2004 came to a close, The Coca Cola Company faced several challenges in the Middle Eastern as well as some European markets. It wasnt so much the Companys products or promotional acumen that was being challenged. The so-called Muslim Colas were redefining the battle at an ideological level. This case illustrates many of the challenges faced by MNCs when brands become ideological symbols. Case Questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. What strategic alternatives are open to The Coca-Cola Company in combating Zam Zam, Mecca and Qibla? Which one would you recommend and why? Was it a good business decision for The Coca-Cola Company to distance itself from U.S. Middle East policy? Why? Why not? What are the risks faced by Zam Zam? Mecca? Qibla? What could be the consequences of the risks you have identified? In your view, are there any ethical or moral problems associated with basing a brand on ideology? Why? Why not?

AUTHOR INFORMATION Praveen Aggarwal (Ph.D. Syracuse University) is Professor of Marketing and Chair of the Department of Marketing in the Labovitz School of Business & Economics at the University of Minnesota Duluth. His research interests are in the areas of consumer decision-making processes, strategic marketing, and price and non-price promotions. Praveen has several years of work experience as a senior executive in the food products industry in India. Kjell R. Knudsen (Ph.D. University of Minnesota) is Associate Professor of Policy and Administrative Behavior and the Dean of the Labovitz School of Business and Economics at the University of Minnesota Duluth. Before joining UMD, he served as Project Manager at the Royal Norwegian Council for Industrial and Scientific Research in Oslo, Norway. He also served for several years as a consultant to the Norwegian Center for Organizational Learning in Oslo, Norway as well as the Foundation for Strategic and Industrial Research in Trondheim, Norway. His research interests include policy formulation and implementation, leadership, management culture, organizational learning, and economic development. Ahmed Maamoun (Ph.D. California Coast University) is Assistant Professor of Marketing in the Labovitz School of Business and Economics at the University of Minnesota Duluth. Ahmed has several years of experience in the field of international business, acquired in multinational companies in the Middle East and New Zealand. He is interested in studying international corporations and how multinationals adjust their strategies to respond to cultural and socio-political differences.

32

Journal of Business Case Studies March/April 2009 REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31.

Volume 5, Number 2

AME Info (2003), Saudi Arabia Bans Zam Zam Cola, August 13. Arabic News (2002), Saudi Arabians Boycott Coca Cola and Pepsi for Iranian Zamzam, August 23. BBC News (2002), Islamic Cola 'Selling Well in Saudi', August 21. BBC News (2003), Islamic Cola launched in the UK, February 4. BBC News (2004), Cola Firm Renews Charity Pledge, August 1. CBC News (2003), The Muslim Cola Wars, February 7. Copenhagen Post Online (2002), Faithful Look Forward to Muslim Cola, October 17. Delves, Philip (2003), Mecca Cola Gives Taste for Anti-Americanism, Telegraph, January 1. Ettinger, Yair (2004), And Now Comes a Political Cola, Haaretz, August 6. Grimston, Jack (2003), British Muslims Find Things Go Better with Mecca, Times, January 19. Gulf News (2003), Arabs React with Dismay and Disbelief, April 8. Haider, Saeed & Al-Harbi, Mohammad (2003), Firm Surprised at Kingdom Ban on Zamzam Cola, Arabic News, July 28. Haider, Saeed (2003), US Cola Giants Getting the Fizz Back in Business, Arabic News, July 31. Henley, Jon & Vasagar, Jeevan (2003), Think Muslim, Drink Muslim, Says New Rival to Coke, Guardian, January 8. Jeffery, Simon (2003), Is it the real thing? Guardian, February 5. Kovach, Gretel (2002), Cola: 'Pepsi' For Palestine, Newsweek, December 16. Los Angeles Times (2008), Cola Makers Target Mideast, February 4. Middle East Times (2002), Iranian Zamzam Cola Hits Saudi Market to Rival US Giants, August 23. Murphy, Verity (2003), Mecca Cola Challenges US Rival, BBC News, January 8. Qadir, Jamila (2003), Mecca Cola Launched in Dubai, Khaleej Times, August 14 Tagliabue, John (2002), They Choke On Coke, But Savor Mecca -Cola, New York Times, December 31. The Coca-Cola Company Annual Report 2004. Theodoulou, Michael & Bremner, Charles & McGrory, Daniel (2002), Cola Wars as Islam Shuns the Real Thing, Times, October 11. The Qibla Cola Company (2003), Qibla Cola Enters Norway to Provide Alternative Soft Drinks to People of Conscious, November 11. The Qibla Cola Company (2004a), Qibla Cola Signs Agreement for Bangladesh Distribution, January 7. The Qibla Cola Company (2004b), Qibla Cola Signs Agreement for Pakistan Distribution, March 25. The Qibla Cola Company (2004c), Qibla Cola Moves to New Premises, September 29. World Intellectual Property Organization (2002), Zam Zam Cola, December 25. Yemen Times (2003a), Mecca Cola Introduced to the Yemeni Market, May 12 -25 Yemen Times (2003b), Mecca Cola Factory in Yemen in May 2004, December 29 -31. Zam Zam Group Home Page. (http://www.zamzamgroup.com/EN/GIHISTORY.ASP)

33

Journal of Business Case Studies March/April 2009 NOTES

Volume 5, Number 2

34

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Case Study Analysis Coors Brewing CompanyDocumento64 pagineCase Study Analysis Coors Brewing Companyipsa2582% (11)

- Case Study BrandDocumento8 pagineCase Study BrandSenthil Kumar Ganesan100% (1)

- The CocaDocumento17 pagineThe Cocalordkhan008Nessuna valutazione finora

- Complete Islamyat BookDocumento110 pagineComplete Islamyat BookNoor Ahmed100% (1)

- The Cola Wars: International Marketing - Case 1Documento11 pagineThe Cola Wars: International Marketing - Case 1api-26094307Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coca-Cola in JapanDocumento19 pagineCoca-Cola in JapanDonde Ke100% (3)

- Case 8 The Coca-Cola Company in JapanDocumento19 pagineCase 8 The Coca-Cola Company in JapanNguyễn Thùy LinhNessuna valutazione finora

- Ammar Aamir 040 Assignment 1Documento5 pagineAmmar Aamir 040 Assignment 1Ammar AamirNessuna valutazione finora

- Case 1 Coca ColaDocumento6 pagineCase 1 Coca ColaSimran JeetNessuna valutazione finora

- Mecca Cola TutoDocumento6 pagineMecca Cola TutoIkram ArifNessuna valutazione finora

- The Coca Cola Company Transnational CorporationDocumento10 pagineThe Coca Cola Company Transnational Corporationapi-301902344Nessuna valutazione finora

- Swot On Coca Cola and PepsiDocumento19 pagineSwot On Coca Cola and PepsiReena GNessuna valutazione finora

- Swot Analysis of CocaDocumento25 pagineSwot Analysis of CocaAkshay Kumar GautamNessuna valutazione finora

- Caso Coca ColaDocumento4 pagineCaso Coca ColaItalo GuaylupoNessuna valutazione finora

- Coca Cola PakistanDocumento27 pagineCoca Cola PakistanWaqar K KharalNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3 Case Study - Globalization and Coca ColaDocumento4 pagineUnit 3 Case Study - Globalization and Coca ColaVera RedNessuna valutazione finora

- Multinational Company Report:: 10 Commerce Will RobertsDocumento7 pagineMultinational Company Report:: 10 Commerce Will RobertsRobboNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Analysis Corona BeerDocumento7 pagineCase Analysis Corona Beerfbl3Nessuna valutazione finora

- Marketing Plan For Coca ColaDocumento14 pagineMarketing Plan For Coca ColaDaw Nan Thida WinNessuna valutazione finora

- Case StudyDocumento9 pagineCase StudyShøùrōv ÄhmĒDNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study 2Documento9 pagineCase Study 2Amna AslamNessuna valutazione finora

- IB SectionA Group12 ReportDocumento15 pagineIB SectionA Group12 ReportSanjeet KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Middle EastDocumento45 pagineMiddle Eastswetaagarwal2706100% (1)

- The Coca-Cola Company Analysis 1. Company Overview 1.1 Executive SummaryDocumento35 pagineThe Coca-Cola Company Analysis 1. Company Overview 1.1 Executive SummaryASAD ULLAHNessuna valutazione finora

- BIG Rock International Expansion PlanDocumento20 pagineBIG Rock International Expansion PlanAly Ihab GoharNessuna valutazione finora

- Cocacola Company HistoryDocumento10 pagineCocacola Company HistoryGlenny MgibaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pepsi Vs CokeDocumento5 paginePepsi Vs CokeNathan RonoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Coca-Cola Company: HistoryDocumento6 pagineThe Coca-Cola Company: HistoryMa PhannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case 12 - Corona BeerDocumento12 pagineCase 12 - Corona BeerRobert Paredes DimapilisNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study NoDocumento13 pagineCase Study NoFobe NudaloNessuna valutazione finora

- Coca Cola PDFDocumento58 pagineCoca Cola PDFANIKET MESTRYNessuna valutazione finora

- Coca ColaDocumento59 pagineCoca ColaSaad Mahmood0% (1)

- Mba508 Molson Coors BrewingDocumento11 pagineMba508 Molson Coors BrewingNigel Psalm Yap100% (1)

- Presentation On Energy DrinkDocumento56 paginePresentation On Energy DrinkRochak RajNessuna valutazione finora

- Pepci CoDocumento3 paginePepci CozeropointwithNessuna valutazione finora

- Soft Drinks in India: Chapter-1Documento53 pagineSoft Drinks in India: Chapter-1nicks012345Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coca Cola FinalDocumento30 pagineCoca Cola Finalshadynader67% (3)

- Case Studies of MMDocumento8 pagineCase Studies of MMsamyukthaNessuna valutazione finora

- Emperador IncDocumento3 pagineEmperador IncRena Jocelle NalzaroNessuna valutazione finora

- Coca ColaDocumento11 pagineCoca ColaFiza Wahla342Nessuna valutazione finora

- SABMILLER MarketingDocumento25 pagineSABMILLER Marketingderek4wellNessuna valutazione finora

- CCBPLDocumento57 pagineCCBPLHasham NaveedNessuna valutazione finora

- Term Project Marketing ManagementDocumento48 pagineTerm Project Marketing ManagementMrunal ShirsatNessuna valutazione finora

- Acquisitions: The Coca-Cola Company (Documento8 pagineAcquisitions: The Coca-Cola Company (Pagal_Aurat_143Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coca-Cola Research.2Documento8 pagineCoca-Cola Research.2CHRISTINE JOY OGOYNessuna valutazione finora

- The Coca-Cola Company - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento11 pagineThe Coca-Cola Company - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAbhishek ThakurNessuna valutazione finora

- MM6Documento6 pagineMM6Lailanie Kay Castillon JaranayNessuna valutazione finora

- Case - CokeDocumento19 pagineCase - Cokekrave_18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Personality:: Clearly Canadian Beverage CorporationDocumento5 paginePersonality:: Clearly Canadian Beverage CorporationnidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Organizational Structure of The Coca Cola CompanyDocumento37 pagineOrganizational Structure of The Coca Cola Companyprasadmahajan26Nessuna valutazione finora

- Describe The Extent of Coca Cola's International Presence?Documento2 pagineDescribe The Extent of Coca Cola's International Presence?Mirha KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Satish RajDocumento41 pagineSatish RajSatish RajNessuna valutazione finora

- The Coca Cola CompanyDocumento7 pagineThe Coca Cola CompanyArun J VasNessuna valutazione finora

- Communications Report Final DraftDocumento24 pagineCommunications Report Final Draftapi-279815457Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coke Vs Pepsi (1999)Documento9 pagineCoke Vs Pepsi (1999)Sidharth Sankar RathNessuna valutazione finora

- Ch02 Coca ColaDocumento5 pagineCh02 Coca ColaShaheed PashaNessuna valutazione finora

- WorldDocumento1 paginaWorldLakshmananKandanathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Brand Breakout: How Emerging Market Brands Will Go GlobalDa EverandBrand Breakout: How Emerging Market Brands Will Go GlobalNessuna valutazione finora

- Secret Formula (Review and Analysis of Allen's Book)Da EverandSecret Formula (Review and Analysis of Allen's Book)Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Gospel of Barnabus Its True ValueDocumento78 pagineThe Gospel of Barnabus Its True ValueMuhammad YusufNessuna valutazione finora

- Ar Radd 'Ala Nuh KellerDocumento14 pagineAr Radd 'Ala Nuh Kellercalikaar500% (1)

- Learn Namaz Sunni Step by Step With Pictures GuidanceDocumento11 pagineLearn Namaz Sunni Step by Step With Pictures GuidanceMD Fuad HasanNessuna valutazione finora

- Developing Standards For Mosque Design in Lahore, Pakistan Muhamamd Ilyas MalikDocumento19 pagineDeveloping Standards For Mosque Design in Lahore, Pakistan Muhamamd Ilyas MalikiriNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of GeographyDocumento8 pagineJournal of GeographyBadrun TamanNessuna valutazione finora

- Martin Nguyen - Modern Muslim Theology - Engaging God and The World With Faith and Imagination (Religion in The Modern World) - Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (2018)Documento222 pagineMartin Nguyen - Modern Muslim Theology - Engaging God and The World With Faith and Imagination (Religion in The Modern World) - Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (2018)benyelles100% (1)

- 14 - Islamic ArchitectureDocumento311 pagine14 - Islamic ArchitectureHilbertCabanlongMangononNessuna valutazione finora

- Enrichment XiiDocumento11 pagineEnrichment Xii'aisyah Jihan 'aliyahNessuna valutazione finora

- Islamic Colonial CPAR Lesson 3Documento30 pagineIslamic Colonial CPAR Lesson 3Alliyah Shane PastorNessuna valutazione finora

- The Dirtection of Qibla (Makkah) : January 1987Documento8 pagineThe Dirtection of Qibla (Makkah) : January 1987FadlanNessuna valutazione finora

- ArchiDocumento9 pagineArchiKristine Mae PastorNessuna valutazione finora

- Grade6 HistoryDocumento138 pagineGrade6 HistoryMubahilaTV Books & Videos OnlineNessuna valutazione finora

- 2058 s07 Ms 2 PDFDocumento7 pagine2058 s07 Ms 2 PDFAbdullah ArifNessuna valutazione finora

- Islamic Center Design With Islamic ArchiDocumento11 pagineIslamic Center Design With Islamic ArchiMuhammad Sufiyan SharafudeenNessuna valutazione finora

- MOSQUEMANAGEMENTDocumento127 pagineMOSQUEMANAGEMENTMahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jumuah Khutbah at Masjidul Haram 23rd August 2013Documento21 pagineJumuah Khutbah at Masjidul Haram 23rd August 2013Zīshān FārūqNessuna valutazione finora

- Surah Baqarah - Structural AnalysisDocumento16 pagineSurah Baqarah - Structural AnalysisKhandkar Sahil RidwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Temple in Jerusalem: Jews JudaismDocumento18 pagineTemple in Jerusalem: Jews JudaismJohnathon Doe100% (2)

- Islamic Architecture Cities: Dr. Raed Al TalDocumento19 pagineIslamic Architecture Cities: Dr. Raed Al TalMehroz BalochNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Pray-Dhahiri FiqhDocumento3 pagineHow To Pray-Dhahiri FiqhBM SplashtimekingNessuna valutazione finora

- SKAMA Inet1428x PDFDocumento242 pagineSKAMA Inet1428x PDFMuneerNessuna valutazione finora

- 005a - Fiqh Syllabus Class 5aDocumento55 pagine005a - Fiqh Syllabus Class 5aJafari MadhabNessuna valutazione finora

- A Brief History of Philippine ArtDocumento19 pagineA Brief History of Philippine ArtJune Patricia AraizNessuna valutazione finora

- Qibla in The Mediterranean: Mo'nica Rius-Pinie SDocumento8 pagineQibla in The Mediterranean: Mo'nica Rius-Pinie SBadrun TamanNessuna valutazione finora

- Qibla Direction MeasurementDocumento11 pagineQibla Direction MeasurementHerdy SadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Interpretation of The Meaning of Mosque Architecture: A Case Study Mosque 99 Cahaya in Lampung, Sumatera Island, IndonesiaDocumento5 pagineInterpretation of The Meaning of Mosque Architecture: A Case Study Mosque 99 Cahaya in Lampung, Sumatera Island, IndonesiaYuda GynandraNessuna valutazione finora

- Tamheed Ul ImanDocumento39 pagineTamheed Ul ImanImtiaz AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Mosque and Social Integration-Ready To PublishDocumento12 pagineMosque and Social Integration-Ready To PublishnurhasanahNessuna valutazione finora

- Sultaniyya - Abdalqadir As-SufiDocumento137 pagineSultaniyya - Abdalqadir As-SufiJabal Sab KadyrovNessuna valutazione finora