Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Jurnal 5 PDF

Caricato da

Ratna Ayu KTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Jurnal 5 PDF

Caricato da

Ratna Ayu KCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Budgeting in the information age: a fresh approach

Jackie Brander Brown Department of Accounting and Finance, The Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK Helen Atkinson School of Service Management, University of Brighton, Eastbourne, UK

Keywords

Accounting systems, Hospitality, Organizational structure

Introduction

As we move forward from the industrial age into today's emerging information age, hospitality organizations face an extremely complex and challenging competitive environment. To compete successfully within such an environment, it is considered imperative that organizational management should focus on anticipating and responding to the ever-changing needs of customers (Hope and Fraser, 1997). Rather than responding to these needs by investing further in their organization's productive capacity, however, it is suggested that management instead need to leverage their organization's knowledge in order to maintain an awareness of external developments and offer an innovative, speedy and quality service to customers (Hope and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Hope, 1997; Fanning, 1999). Accordingly, it is claimed that the main competitive constraint for organizations is no longer financial capital, as in the industrial age, but rather the primary limiting resource in the information age is, and will progressively be, that of intellectual capital (Hope and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Hope, 1997). For such a change in management emphasis to be fully effective, it is argued that a new organizational structure is required which, in addition, will need to be supported by more appropriate forms of accounting control systems (Hope and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Hope, 1997). The multi-divisional (M-form) organizational structure, which was ``in tune'' with the industrial age emphasis on volume and productivity, is thought to be too bureaucratic and unresponsive for the needs of organizations in the information age. Instead, it is proposed that a leaner, more

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at http://www.emerald-library.com/ft

For hospitality organizations to compete successfully in the emerging information age, with its emphasis on innovation, quality and speed, it is suggested that they must adopt more flexible, responsive and empowered management structures. However, if such developments are to prove effective, it is essential that hospitality organizations also overhaul their accounting systems, most of which were designed to support the previous industrial era's focus on volume and productivity. Indeed, there is a concern that traditional budgeting systems with their typical bureaucratic encouragement of internally-focused, departmentcentred cost minimization may present a significant barrier to effective change. It is proposed instead that a fresh approach to the objectives of budgeting is needed, involving ``alternative steering mechanisms'' that promote empowerment, flexibility and knowledge-sharing. This suggestion is supported by evidence from an American hotel where such a fresh approach to budgeting has been developing, ``matching'' its more progressive management structure.

Abstract

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 13/3 [2001] 136143 # MCB University Press [ISSN 0959-6119]

responsive and empowering network (Nform) model will be more effective (Bartlett and Goshal, 1996; Hope and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Hope, 1997). Unfortunately, though, as companies have attempted to develop these more flexible management approaches, it has been identified that they often fail to fully support these changes by, at the same time, substantially overhauling their accounting control systems most of which were designed to fit the earlier industrial era (Hope and Fraser, 1997). In particular, there is considerable concern that traditional budgeting systems, with their typical encouragement of internally focused, department-centred costminimization, may present a very significant barrier to effective change (Bunce and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Fraser, 1997). Consequently, it is proposed that a completely fresh approach to the objectives of budgeting is needed one which especially promotes the information age emphasis on empowerment, flexibility and knowledge-sharing (Bunce and Fraser, 1997). This article opens by summarizing the suggested developments in management structures as organizations progress from the industrial era into the information age. Limitations associated with traditional approaches to budgeting systems are then outlined, together with proposed new approaches to the main purposes of budgets. A review of budgetary control as currently practised in hospitality organizations is then presented, including the identification of emerging developments. Then, empirical evidence concerning the management structure and budgetary control systems of an American hotel that appears to be adapting well to the information age is considered, before the article finally concludes with the proposal of a fresh approach to budgeting within the hospitality industry.

[ 136 ]

Jackie Brander Brown and Helen Atkinson Budgeting in the information age: a fresh approach International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 13/3 [2001] 136143

Developments in management structures

It is widely accepted that the M-form management structure, as illustrated in Figure 1, was an appropriate and effective organizational form for the industrial age, with its focus on the traditional limiting factors of finance, land and labour (Hope and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Hope, 1997). This approach to organizational management views senior management as the fundamental source of an organization's experience and knowledge, with their primary roles being that of strategy formulation and resource allocation. Middle management, meanwhile, is regarded as being responsible for maintaining organizational control, while the front-line managers are seen as being the organization's implementers (Anthony, 1965; Anthony and Govindarajan, 1995; Hope and Fraser, 1997). Indeed, Hope and Fraser consider that overall it is an approach that particularly embodies the management philosophy prevalent in the industrial era of command and control, contract and compliance. However, whilst this M-form organizational model is considered to have been ``in tune'' with its time, it is increasingly viewed as being too bureaucratic and unresponsive for today's information age organizations, especially as Hope and Fraser, (1997, p. 21) argue that ``. . . it creates a culture that is risk averse and gives a false sense of security . . .'' . Instead, it is suggested that a new management structure, such as the N-form model illustrated in Figure 2, is needed if today's organizations are to compete successfully in

Figure 1 M-Form management structure

an age when the key limiting factor is an organization's intellectual capital which, it is suggested, includes the important organizational elements of competent management, enthusiastic and skilled workers, strong brands and loyal customers (Bartlett and Goshal, 1996; Hope and Fraser, 1997). In this respect it is especially interesting to note that intellectual capital has been found to form the major part of the market value of many companies today while, moreover, empirical evidence also seems to indicate that those companies which have focused on building their intellectual capital have not only provided excellent returns for their owners, but have also consistently outperformed the competition (Hope and Fraser, 1997). As indicated in Figure 2, this N-form approach to management treats the organization's front-line managers as the entrepreneurs, with responsibility for strategy and decision making. The organization's middle managers are then viewed as being integrators supporting the development of competencies both within the organization as well as with external partners, while top management are responsible for providing inspiration and a sense of purpose, and for challenging an organization's ongoing ideas and processes (Bartlett and Goshal, 1996; Hope and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Hope, 1997). Such a model, which is underpinned by a focus on maximizing value rather than costminimization, is considered to be much more in tune with the information age management philosophy of enterprise and responsibility, trust and loyalty. Moreover, given that it is considered to be more marketoriented as well as more organic and responsive, it is thus thought to be far more appropriate for organizations competing in the information age (Bartlett and Goshal, 1996; Hope and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Hope, 1997). A significant number of well-established organizations in a variety of industries including, for example, IKEA, Volvo, Handels Banken, Asea Brown Boveri and HewlettPackard have already adopted such a flexible, empowered management structure. Moreover, they have also incorporated into their management control systems such associated developments as total quality management (TQM), business process reengineering (BPR), economic value added (EVA) and the balanced scorecard. However, many organizations that have similarly attempted to thus ``shift'' themselves into the information age have, unfortunately, found their efforts stifled principally as they come

[ 137 ]

Jackie Brander Brown and Helen Atkinson Budgeting in the information age: a fresh approach International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 13/3 [2001] 136143

up against the very significant barrier presented by traditional budgeting systems (Bunce and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Hope, 1997).

Traditional budgeting systems: concerns and suggestions

Concerns regarding a number of limitations and weaknesses that have been linked to traditional budgeting processes are becoming increasingly widespread, with the primary ``fear'' being that they could potentially hinder and damage an organization's performance (Bunce and Fraser, 1997). For the most part, these concerns fall into one of two main categories: that the process is inefficient and, furthermore, that it is ineffective.

and the pursuit of continuous improvement; that they strengthen the traditional vertical chain of command rather than empowering the people on the organization's front line; and that they emphasize cost-minimization rather than the maximizing of value (Bunce and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Fraser, 1997). Overall, it is considered that such budgeting systems often fail to give lasting improvement or generate congruent behaviour (Bunce and Fraser, 1997; Fanning, 1999) indeed, Hope and Hope (1997) summarize the situation by concluding that:

. . . the budgeting process is too rigid, too internally focused, adds too little value, takes too much management time, and encourages the wrong managerial behaviour . . .

With regard to being inefficient, for instance, it is generally considered that the traditional budgeting process is very bureaucratic and protracted (Bunce and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Fraser, 1997; Fanning, 1999). In particular, it is claimed that budgets take up too much management time, often involving numerous revisions and substantial delays (Fanning, 1999). Significant concerns regarding the apparent ineffectiveness of traditional budgets, meanwhile, include: that typically such budgets encourage parochial behaviour, reinforcing departmental barriers while hindering flexibility, responsiveness and knowledge sharing; that they are seen as a rigid commitment, constraining management to out-of-date assumptions while inhibiting both management initiative

Budgeting systems: concerns about inefficiencies and ineffectiveness

It is suggested that a significant number of these problems of inefficiency and ineffectiveness relate to the fact that traditional budgeting systems were actually initially designed just as an aid to financial forecasting, cash flow management and the control of costs and capital expenditure. In recent times, though, budgets have also been utilized to support such important management functions as communicating and determining corporate goals and objectives, allocating resources and appraising performance functions for which the budgetary control system was never designed, and for which it is not at all well suited (Bunce and Fraser, 1997). It is perhaps not surprising then that it is considered that the traditional budgeting system is ``out of sync'' with the needs of organizations in the information age and that a new approach to achieving management's purposes for budgeting is needed (Hope and Fraser, 1997; Hope and Hope, 1997).

Figure 2 N-Form management structure

It has been suggested that it may be possible to meet the budgetary needs of organizations in the information age through adopting ``better budgeting'' processes including, for example, activity based budgeting (ABB) and zero-base budgeting (ZBB) (Fanning, 1999). However, it is being increasingly argued that just ``tinkering'' with an organization's budgeting systems will not be adequate. Instead, it is suggested that what is really needed is a fundamentally new approach to such important budgeting purposes as forecasting and resource allocation, performance measurement and control, and cost management an approach which incorporates a range of ``alternative steering mechanisms'' that especially

Budgeting systems: suggested new approaches

[ 138 ]

Jackie Brander Brown and Helen Atkinson Budgeting in the information age: a fresh approach International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 13/3 [2001] 136143

promote empowerment, flexibility and knowledge-sharing (Hope and Fraser, 1997). More specifically, researchers such as Hope and Fraser propose that the important functions of forecasting and resource allocation would be better achieved through the use of rolling forecasts, which should be prepared quickly and updated when required and which should not be constrained by the traditional annual planning cycle. Also, as these forecasts will need to be as objective and accurate as possible, they will necessitate good access to relevant external indicators as well as the swift and open transmission of key data around the organization. In the meantime, Hope and Fraser also anticipate that the purposes of performance measurement and control will no longer be based on the traditional ``actual versus budget'' comparison, but rather will be focused on strategic milestones and relative measures all determined within the context of a balanced scorecard framework. Furthermore, they consider that effective cost management will be better achieved by supporting the development of an organizational culture based on adding value and continuous improvement reinforced by an organization-wide, long-term reward system. Particularly useful tools that may be adopted in this respect include activity based management (ABM) and benchmarking.

Budgeting systems in the hospitality industry

Given the previously noted concerns regarding traditional approaches to budgeting, it is interesting to note that research undertaken with regard to the use of such systems within the hospitality industry has identified that operations of all sizes appear to place considerable importance on their traditional budgeting activities (DeFranco, 1997), utilizing them on a regular basis and viewing them as a potentially valuable control tool (Brander Brown, 1995). Furthermore, the development of ``bottom-up'', participative approaches to budget determination as well as other more sophisticated budgetary control techniques are becoming increasingly widespread especially in multi-unit operations (Schmidgall and Ninemeier, 1987; Schmidgall et al., 1996), while the use of more simplified systems has been viewed as being more appropriate for smaller and/or single unit operations, or where perceptions of environmental uncertainty are high (Rusth, 1990).

Underpinning this apparently favourable opinion, and related widespread usage of traditional budgeting systems, are a number of perceived benefits including, for example, that such budgets can assist managers in setting positive targets both for themselves and for other employees (Schmidgall, 1995). Furthermore, Schmidgall also suggests that such targets, when properly used, can provide a positive motivating influence, supporting the achievement of an organization's aims. It has, however, also been apparent for some time that a number of problems and limitations have been associated with the use of such traditional budgeting processes within the hospitality industry. For instance, it is claimed that hospitality budgetary control systems typically demonstrate something of an adversarial nature (Pickup, 1985), and that where management and employees either do not actively participate in the budget process and/or where budget targets are seen as being unattainable, then a number of serious dysfunctional consequences such as gameplaying, and feelings of tension and mistrust may emerge, with potentially detrimental implications for an organization (O'Dea, 1985; Pickup, 1985; Ferguson and Berger, 1986; Brander Brown, 1995). Moreover, it has been noted that multi-unit operations have tended to adopt standardized budgeting systems (Rusth, 1990), which do not permit the particular circumstances of an individual operation to be fully reflected, while it has also been asserted that the form of budgetary control systems typically in use is neither sufficiently flexible nor comprehensive (Schmidgall and Ninemeier, 1987; Eder and Umbreit, 1987). Suggested improvements to overcome such perceived limitations include the provision of higher levels of properly controlled and co-ordinated information (Schmidgall and Ninemeier, 1987), and the incorporation of a wider range of indicators including more qualitative data (Eder and Umbreit, 1987). Additionally and, perhaps, reflecting the increasing complexity and competitiveness of the industry, a range of other suggested improvements and developments have also recently begun to (re)materialize. For instance, although the need for more clearly identified management information needs including in relation to budgets is long-established (Bullen and Rockart, 1981; Geller, 1984), calls for more up-to-date, relevant critical success factors are again being heard (Jones, 1995; Brotherton and Shaw, 1996; Atkinson and Brander Brown, 2000). Similarly, despite the fact that it has been recognized for some

[ 139 ]

Jackie Brander Brown and Helen Atkinson Budgeting in the information age: a fresh approach International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 13/3 [2001] 136143

time that planning within the hospitality industry should be proactive rather than reactive, involving the anticipation of possible alternative scenarios (Lee and Powell, 1972; Rusth and Lefever, 1988), it is apparent that such associated tools as flexible budgetary control have not, as yet, been widely used (Collier and Gregory, 1995; Harris and Brander Brown, 1998). The proposed need for a more proactive budgetary approach, however, appears to be emerging again, with a recent study involving a number of high standard, fullservice hotels having identified a growing emphasis on the use of regular re-forecasts and updates of projected performance attainment (Brander Brown, 1998; Brander Brown, in progress). This study has also identified a number of other developing improvements with regard to hotel budgeting systems, including: the explicit inclusion of critical external factors, both with regard to forecasts as well as subsequent performance comparisons; the establishment of more detailed formats for budget reports, considerably beyond that available using a Uniform Systems of Account approach; and the substantial reorganization of budgeting systems so as to better fit more flexible organizational structures (Brander Brown, 1998; Brander Brown, in progress). Such noted developments are already well under way at the Lakefront Hotel an American property that certainly appears to be adapting well to the challenges of the information age.

especially aimed at generating a flexible and entrepreneurial spirit, promoting the taking of risks and the trying out of new ideas while still ensuring effective responsibility and accountability. This IBU approach also places a considerable emphasis on empowerment, teamwork and knowledgesharing encouraging the hotel's front-line management and staff to use their initiative and ``do what they've been trained to do'' in order to provide outstanding guest service. The Lakefront's management approach is also underpinned by a strong belief in the hotel's mission to ``. . . distance ourselves from the competition . . .''. In relation to this there is a clear focus within the Lakefront on continuous improvement, with recent management advances within the hotel including: the appointment of a Director of TQM driving the design and implementation of innovative quality processes; the investigation and subsequent development of activity based costing techniques, especially with regard to market segment profitability; and the deliberate embracing of a longer-term balanced approach to performance incorporating not only an external, market-oriented focus but also involving more qualitative internal information concerning employee morale and guest satisfaction. A telling overall summary of the hotel's management approach was provided by one IBU manager who summarized that ``. . . the status quo is not acceptable . . .'' at the Lakefront an approach that seems well suited to the challenges of the information age. Not only has the Lakefront developed a management approach suited to the information age, it is also well on the way to developing a range of control systems and tools which more effectively address the fundamental purposes associated with traditional approaches to budgeting and which are thus more appropriately matched to this N-form structure. For example, with regard to forecasting and resource allocation, the Lakefront's annual plan is supplemented by frequent revised forecasts and updates. These plans and re-forecasts, which incorporate highquality external data as, for instance, provided through regular (STaR) reports provided about the Chicago market by Smith Travel Research are developed through team-working, and are openly communicated to all management and staff by utilizing the hotel's internal computer network.

Empirical evidence: the Lakefront Hotel

The 1,200 room Lakefront Hotel (the Lakefront) is a high-standard, full-service property located in Chicago, adjacent to Lake Michigan and close to both the city's main business district and its ``Magnificent Mile'' shopping area. The hotel is widely viewed as being a ``flagship'' operation within the wellestablished international company which is responsible for managing the property a position which, in significant part, reflects its progressive management approach. The Lakefront's on-site management team includes a managing director, a five member advisory board and ten independent business and/or service unit managers (IBUs). This N-form type arrangement (illustrated in Figure 3) is known within the Lakefront as the ``IBU system of management', and is

The Lakefront's budgeting systems

The Lakefront's management approach

[ 140 ]

Jackie Brander Brown and Helen Atkinson Budgeting in the information age: a fresh approach International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 13/3 [2001] 136143

The Lakefront has, in addition, deliberately developed a more balanced approach to its performance management and control. For instance, the hotel's performance information specifically includes both external and internal quantitative data as well as broader, ``softer'' evaluations of key areas of performance. Moreover, these indicators are especially focused on ``new'' critical indicators that have been established for the whole property as well as for each individual IBU. The performance information provided is also widely disseminated to all the hotel's management and staff, both through the computerized internal network as well as through visual ``dashboards'' that are on display in each IBU as well as in the staff cafe . With regard to hotel's cost management activities, meanwhile, and as already noted, the Lakefront has established a culture of continuous improvement, including the active encouragement of empowerment and teamwork and the exercising of initiative to ``add value''. Alongside this, the hotel has also begun to incorporate and develop a number of more advanced control tools including TQM, ABC and benchmarking. The Lakefront, however, has also identified and is addressing a number of possible problem areas which will need to be faced by any hospitality organization trying to develop its management structures and control systems for the information age. More specifically, it is considered vital that the adoption of an N-form management approach should not be permitted to foster unhealthy competition between front-line management and staff. Experience at the Lakefront would seem to suggest that such a potentially damaging situation can be

avoided by encouraging all management and staff to focus on the interests of the guests and of the overall hotel. Furthermore, although continuing improvements in information technology make the provision of very detailed information and the frequent updating of plans possible, it is also considered that with regard to enhancing efficiency and effectiveness, the relative costs and benefits of undertaking such activities need to be more fully appreciated.

A fresh approach to budgeting in the hospitality industry

Drawing together the proposed generic alternative steering mechanisms noted previously, together with the suggested improvements being called for within the hospitality industry and the developments which have already taken place at the Lakefront, a fresh approach to the main purposes of budgeting within the hospitality industry can be construed an approach which should more effectively support the more flexible, responsive, empowered N-form organizational model. In particular, it is proposed that in relation to the purpose of forecasting and resource allocation, detailed updates of projected performance attainment should be produced on a relatively frequent basis. These updates should not, in any way, be restricted by an organization's financial reporting cycle, but rather should respond to significant identified and/or anticipated movements in the organization's critical success factors. Furthermore, these updates should be communicated widely and on a very timely basis, primarily using internal computer networks and/or dashboards. With regard to the performance measurement and control aspect of budgeting systems, meanwhile, it is suggested that hospitality organizations need to develop a balanced range of performance indicators. These should incorporate strategic indicators of an operation's ``drivers'' of future performance as well as shorter-term measures regarding results actually achieved. In addition, it is also considered important that these performance indicators also include a number of objective and reliable market-oriented benchmarks. Furthermore, in order to better support effective cost management within an Nform organization, hospitality organizations will need to develop an

Lessons from The Lakefront

Figure 3 The Lakefront Hotel organizational structure

[ 141 ]

Jackie Brander Brown and Helen Atkinson Budgeting in the information age: a fresh approach International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 13/3 [2001] 136143

organizational culture which focuses on continuous improvement and adding-value. Alongside the potential adoption of such well-known techniques as TQM, ABM and benchmarking in this respect, it is an approach that will also necessitate the active encouragement of empowered creativity and knowledge-sharing. Finally, whilst the hotel accounting team will obviously have a role in assisting management to appreciate the balance of costs and benefits associated with such proposals, it also appears likely that such developments will demand a proactive and involved accounting team, working handin-hand with management to enable hospitality organizations to cope more effectively with the challenges of the information age.

Anthony, R. (1965), Planning and Control Systems: A Framework for Analysis, Harvard Graduate School of Business, Boston, MA. Anthony, R. and Govindarajan, V. (1995), Management Control Systems, Irwin, Chicago, IL. Atkinson, H. and Brander Brown, J. (2000), ``Performance measurement systems in the UK hotel industry: rethinking the folly of measuring the wrong things?'', Proceedings of the Ninth Annual CHME Hospitality Research Conference, University of Huddersfield. Bartlett, C.A. and Goshal, S. (1996), ``Beyond the M-form: toward a managerial theory of the firm'', http//www.gsia.cmu.deu/bosch/ bart.html. Brander Brown, J. (1995), ``Management control in the hospitality industry: behavioural implications'', in Harris, P.J. (Ed.), Accounting and Finance for the International Hospitality Industry, ButterworthHeinemann, Oxford. Brander Brown, J. (1998), ``Towards an understanding of the relationship between organizational culture and accounting controls: a case study from the US hotel industry'', paper presented at the British Accounting Association Annual Conference, the Manchester Conference Centre, UMIST. Brander Brown, J. (in progress) ``Relating organizational culture and accounting control systems in an industry context: a grounded theory for the hotel industry'', PhD thesis in progress, Oxford Brookes University. Brotherton, B. and Shaw, J. (1996), ``Towards an identification and classification of critical success factors in UK hotels plc'', International Journal of Contemporary

References

Hospitality Management, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 113-35. Bullen, C.V. and Rockart, J.F. (1981), A Primer on Critical Success Factors, Working Paper No. 69, Centre for Information Systems, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, MA. Bunce, P. and Fraser, R. (1997), ``Beyond budgeting . . .'', Management Accounting, February, p. 26. Collier, P. and Gregory, A. (1995), Management Accounting in Hotel Groups, Chartered Institute of Management Accountants, London. DeFranco, A.L. (1997), ``The importance and use of financial forecasting and budgeting at the department level as perceived by hotel controllers'', Hospitality Research Journal, Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 99-110. Eder, R.W. and Umbreit, W.T. (1987), ``Measures of management effectiveness in the hotel industry'', Hospitality Education and Research Journal, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 333-41. Fanning, J. (1999), ``Budgeting in the 21st century'', Management Accounting, November, pp. 24-5. Ferguson, D.H. and Berger, F. (1986), ``The human side of budgeting'', The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 87-90. Geller, A.N. (1984), Executive Information Needs in Hotel Companies, Peat, Marwick, Mitchell & Co., Houston, TX. Harris, P.J. and Brander Brown, J. (1998), ``Research and development in hospitality accounting and financial management'', International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 17, pp. 161-81. Hope, J. and Fraser, R. (1997), ``Beyond budgeting . . . breaking through the barrier to the third wave'', Management Accounting, December, pp. 20-3. Hope, T. and Hope, J. (1997), ``Chain reaction'', People Management, September, pp. 26-31. Jones, T.A. (1995), ``Identifying managers' information needs in hotel companies'', in Harris, P.J. (Ed.), Accounting and Finance for the International Hospitality Industry, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford. Lee, R.W. and Powell, E.W. (1972), ``Profit planning: the continuing feasibility study'', The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 79-86. O'Dea, W. (1985), ``Budgetary control: a behavioural perspective'', International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 179-80. Pickup, I. (1985), ``Budgetary control within the hotel industry'', International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 4 No. 4, pp. 149-55. Rusth, D.B. (1990), ``Hotel budgeting in a multinational environment: results of a pilot

[ 142 ]

Jackie Brander Brown and Helen Atkinson Budgeting in the information age: a fresh approach International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 13/3 [2001] 136143

study'', Hospitality Research Journal, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 217-22. Rusth, D.B. and Lefever, M.M. (1988), ``International profit planning'', The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 29 No. 3, pp. 68-73. Schmidgall, R.S. (1995), Hospitality Industry Managerial Accounting, The Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Motel Association, East Lansing, MI.

Schmidgall, R.S. and Ninemeier, J.D. (1987), ``Budgeting in hotel chains: co-ordination and control'', The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 79-84. Schmidgall, R.S., Borchgrevink, C.P. and ZahlBegnum, O.D. (1996), ``Operations budgeting practices of lodging firms in the United States and Scandinavia'', International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 189-203.

[ 143 ]

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Becker, B. E., & Huselid, M. A. 1998. High Performance Work PDFDocumento25 pagineBecker, B. E., & Huselid, M. A. 1998. High Performance Work PDFÁtila de AssisNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Philosophy of The Human Person - 2nd QuarterDocumento5 pagineIntroduction To Philosophy of The Human Person - 2nd Quarternamjoonsfluff100% (1)

- Tracing Practice Preschool Workbook PDFDocumento20 pagineTracing Practice Preschool Workbook PDFO ga100% (3)

- Beyond Budgeting - ArticlesDocumento32 pagineBeyond Budgeting - Articlesagarai100% (1)

- Concept of Knowledge ManagementDocumento13 pagineConcept of Knowledge ManagementzoeltyNessuna valutazione finora

- Book Summary - Assignment - Wycliffe - Okelo (200447259)Documento33 pagineBook Summary - Assignment - Wycliffe - Okelo (200447259)Wycliffe OkeloNessuna valutazione finora

- Question One (3 Marks) : Bsmh5023 Strategic Human Resource ManagementDocumento2 pagineQuestion One (3 Marks) : Bsmh5023 Strategic Human Resource ManagementZulaihaAmariaNessuna valutazione finora

- SSRN Id1456709Documento27 pagineSSRN Id1456709Chai LiNessuna valutazione finora

- 5.0 Predicting The Future Approach of Corporate Finance: The New Financial ParadigmDocumento5 pagine5.0 Predicting The Future Approach of Corporate Finance: The New Financial ParadigmsyaidatulNessuna valutazione finora

- Behind The Habits..Documento22 pagineBehind The Habits..Neha ChopraNessuna valutazione finora

- Clayton M. Christensen et al (2010). Innovation Killers: How Financial Tools Destroy Your Capacity to Do New Things (Boston: Harvard Business School Press), Harvard Business Review Classics Series, pp. 49, p/b, ISBN 978-1-4221-3655-3Documento6 pagineClayton M. Christensen et al (2010). Innovation Killers: How Financial Tools Destroy Your Capacity to Do New Things (Boston: Harvard Business School Press), Harvard Business Review Classics Series, pp. 49, p/b, ISBN 978-1-4221-3655-3International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Manchester Metropolitan University Shiga University University of HertfordshireDocumento33 pagineManchester Metropolitan University Shiga University University of HertfordshireAmber HendersonNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 SM PDFDocumento10 pagine1 SM PDFEth Fikir NatNessuna valutazione finora

- Final PaperDocumento15 pagineFinal PaperGregory HilgendorfNessuna valutazione finora

- Management Accounting Systems in Islamic and Conventional Financial Institutions in MalaysiaDocumento24 pagineManagement Accounting Systems in Islamic and Conventional Financial Institutions in MalaysiadestiyuniNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Management and Decision Making Among Micro Business in Tagum CityDocumento29 pagineFinancial Management and Decision Making Among Micro Business in Tagum CityHannah Wynzelle Aban100% (1)

- Frow Et Al. Budgeting 2010Documento18 pagineFrow Et Al. Budgeting 2010Mekala jaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Emerging Patterns of Management Accounting Research: Anthony G. Hopwood Michael BromwichDocumento2 pagine1 Emerging Patterns of Management Accounting Research: Anthony G. Hopwood Michael BromwichTayyaba ArifNessuna valutazione finora

- Can Enterprises Function Without The BudgetDocumento20 pagineCan Enterprises Function Without The BudgetIwora AgaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study SubmissionDocumento3 pagineCase Study SubmissionIosif LafazanidisNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial ManagementDocumento27 pagineFinancial ManagementMohamed KotbNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic Management Literature ReviewDocumento8 pagineStrategic Management Literature Reviewafdtrajxq100% (1)

- The Tyranny of The Balanced Scorecard in The Innovation EconomyDocumento19 pagineThe Tyranny of The Balanced Scorecard in The Innovation EconomybrankodNessuna valutazione finora

- The Influence of Innovation in Tangible and Intangible Resource Allocation: A Qualitative Multi Case StudyDocumento21 pagineThe Influence of Innovation in Tangible and Intangible Resource Allocation: A Qualitative Multi Case StudyMATHILDA ANGELA DENISE R. REYESNessuna valutazione finora

- Budgetary ControlDocumento58 pagineBudgetary ControlGrantha Gangamma100% (2)

- Business KabuDocumento5 pagineBusiness KabuZED360 ON DEMANDNessuna valutazione finora

- Budget and Budgetary ControlDocumento13 pagineBudget and Budgetary ControlMaheshKumarChinniNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic and Social Significance of BudgetsDocumento16 pagineEconomic and Social Significance of BudgetsAysel SalahovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Upravljanje Ljudskim Resursima: Fakultet Za Poslovne Studije I PravoDocumento16 pagineUpravljanje Ljudskim Resursima: Fakultet Za Poslovne Studije I PravoNinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Knowledge Management Practices in The Banking Industry: Present and Future State - Case StudyDocumento12 pagineKnowledge Management Practices in The Banking Industry: Present and Future State - Case StudylizakhanamNessuna valutazione finora

- Sidrah Rakhangi - TP059572Documento12 pagineSidrah Rakhangi - TP059572Sidrah RakhangeNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of Transformational Leadership, Organisational Learning and Technological Innovation On Strategic Management Accounting in Thailand's Financial InstitutionsDocumento24 pagineEffects of Transformational Leadership, Organisational Learning and Technological Innovation On Strategic Management Accounting in Thailand's Financial InstitutionsdiahNessuna valutazione finora

- Cost Information and Business StrategyDocumento10 pagineCost Information and Business StrategyAli JumaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Paper 5 - Budgets - EARDocumento22 paginePaper 5 - Budgets - EARRuiCarvalhoNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis 2Documento21 pagineThesis 2Nsemi NsemiNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study On "Financial Planning and Forecasting": Tirupathi Mahesh Dr. K. Veeraiah Ms. O. AyeeshaDocumento11 pagineA Study On "Financial Planning and Forecasting": Tirupathi Mahesh Dr. K. Veeraiah Ms. O. Ayeeshaaditya devaNessuna valutazione finora

- Victoria University of Bangladesh: Anstotheqno-1Documento12 pagineVictoria University of Bangladesh: Anstotheqno-1Md Shadat HossainNessuna valutazione finora

- Total SummaryDocumento6 pagineTotal SummaryRomel ChakmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mergers and Acquisition EssayDocumento5 pagineMergers and Acquisition EssayAidaalNessuna valutazione finora

- Hamdan 2017Documento16 pagineHamdan 2017andiniaprilianiputri84Nessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Management ReportDocumento24 pagineFinancial Management Reportilyasabdullah984Nessuna valutazione finora

- Marks and SpencerDocumento11 pagineMarks and SpencerShafaqat AlamNessuna valutazione finora

- Issues of HRDocumento6 pagineIssues of HRsaba kurawleNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is HR Strategy?Documento4 pagineWhat Is HR Strategy?khanlodhiNessuna valutazione finora

- Dissertation On Budgetary Control and Financial Performance of Insurance Companies in Makati CityDocumento28 pagineDissertation On Budgetary Control and Financial Performance of Insurance Companies in Makati CityMaggie Deocareza100% (1)

- HRM in Marks & SpencerDocumento8 pagineHRM in Marks & SpencerLinh CaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Strategy As A Situational Factor of Subsidiary PMSDocumento11 pagineBusiness Strategy As A Situational Factor of Subsidiary PMSPutrisa Amnel VianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis Firm PerformanceDocumento6 pagineThesis Firm Performancewguuxeief100% (2)

- Entrepreneurial - Ecosystems - and - Growth-Oriented EntrepreneurshipDocumento38 pagineEntrepreneurial - Ecosystems - and - Growth-Oriented Entrepreneurshiprocha09mNessuna valutazione finora

- Managers' Perception of Potential Impact of Knowledge Management in The Workplace: Case StudyDocumento8 pagineManagers' Perception of Potential Impact of Knowledge Management in The Workplace: Case StudyUsman RashidNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Papers Strategic Management AccountingDocumento5 pagineResearch Papers Strategic Management Accountingfvf6r3arNessuna valutazione finora

- Review Literature Linking Corporate Performance Mergers AcquisitionsDocumento8 pagineReview Literature Linking Corporate Performance Mergers Acquisitionsc5qvf1q1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Wayne Cascio and John Bourdreau InvestinDocumento4 pagineWayne Cascio and John Bourdreau InvestinLuis AlbertoNessuna valutazione finora

- Integrated Reporting, Corporate Governance, and The Future of The Accounting FunctionDocumento6 pagineIntegrated Reporting, Corporate Governance, and The Future of The Accounting FunctionAnonymous D40DzEztJbNessuna valutazione finora

- Toward A Balanced Scorecard For Higher Education: Rethinking The College and University Excellence Indicators FrameworkDocumento10 pagineToward A Balanced Scorecard For Higher Education: Rethinking The College and University Excellence Indicators FrameworkAmu CuysNessuna valutazione finora

- TopicDocumento4 pagineTopicSoumitree MazumderNessuna valutazione finora

- Beyond BudgetingDocumento5 pagineBeyond BudgetingNahid HamidNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample 2Documento13 pagineSample 2Snehashis SahaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Stages of Shifting To HRM From Personnel ManagementDocumento3 pagineThe Stages of Shifting To HRM From Personnel ManagementFarheen Ahmed100% (1)

- The Application of The Beyond Budgeting To Organisations - An Example of Application of Borealis CompanyDocumento11 pagineThe Application of The Beyond Budgeting To Organisations - An Example of Application of Borealis CompanyHritik ShoranNessuna valutazione finora

- Employee Engagement PDFDocumento7 pagineEmployee Engagement PDFRatna Ayu KNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal KeuanganDocumento29 pagineJurnal KeuanganRatna Ayu KNessuna valutazione finora

- Ownership and ProfitabilityDocumento21 pagineOwnership and ProfitabilityRatna Ayu KNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 Dan Chapter 3 (Pasar Modal Dan Investasi)Documento8 pagineChapter 2 Dan Chapter 3 (Pasar Modal Dan Investasi)Ratna Ayu KNessuna valutazione finora

- Saffi 2010Documento32 pagineSaffi 2010Ratna Ayu KNessuna valutazione finora

- 17 Impact of Short Selling Activity On Market Dynamics Evidence From An Emerging Market PDFDocumento27 pagine17 Impact of Short Selling Activity On Market Dynamics Evidence From An Emerging Market PDFRatna Ayu KNessuna valutazione finora

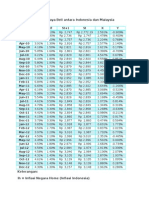

- Paritas Daya Beli Antara Indonesia Dan MalaysiaDocumento6 pagineParitas Daya Beli Antara Indonesia Dan MalaysiaRatna Ayu KNessuna valutazione finora

- Indonesia V.S Malaysia: PERIODE 2010-2012Documento12 pagineIndonesia V.S Malaysia: PERIODE 2010-2012Ratna Ayu KNessuna valutazione finora

- Penyelarasan Instrumen Pentaksiran PBD Tahun 2 2024Documento2 paginePenyelarasan Instrumen Pentaksiran PBD Tahun 2 2024Hui YingNessuna valutazione finora

- Resumen CronoamperometríaDocumento3 pagineResumen Cronoamperometríabettypaz89Nessuna valutazione finora

- Design and Fabrication Dual Side Shaper MachineDocumento2 pagineDesign and Fabrication Dual Side Shaper MachineKarthik DmNessuna valutazione finora

- Substation DiaryDocumento50 pagineSubstation Diaryrajat123sharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Simple Stress & StrainDocumento34 pagineSimple Stress & StrainfaisalasgharNessuna valutazione finora

- Duncan Reccommendation LetterDocumento2 pagineDuncan Reccommendation LetterKilimanjaro CyberNessuna valutazione finora

- TG Comply With WP Hygiene Proc 270812 PDFDocumento224 pagineTG Comply With WP Hygiene Proc 270812 PDFEmelita MendezNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Forensic Science Questioned DocumentsDocumento50 pagineIntroduction To Forensic Science Questioned DocumentsLyka C. De Guzman100% (2)

- TS en 12697-6 A1 Yoğunluk Ve Öz Kütle Tayi̇ni̇Documento17 pagineTS en 12697-6 A1 Yoğunluk Ve Öz Kütle Tayi̇ni̇DEFNENessuna valutazione finora

- Work Performance Report in Project ManagementDocumento3 pagineWork Performance Report in Project Managementmm.Nessuna valutazione finora

- CVE 202 Lecture - 28062021Documento11 pagineCVE 202 Lecture - 28062021odubade opeyemiNessuna valutazione finora

- SLE Lesson 7 - Weather CollageDocumento4 pagineSLE Lesson 7 - Weather CollageKat Causaren LandritoNessuna valutazione finora

- IB Source CatalogDocumento145 pagineIB Source Catalogeibsource100% (2)

- Catalog BANHA FINAL OnlineDocumento65 pagineCatalog BANHA FINAL OnlineHomeNessuna valutazione finora

- Formalization of UML Use Case Diagram-A Z Notation Based ApproachDocumento6 pagineFormalization of UML Use Case Diagram-A Z Notation Based ApproachAnonymous PQ4M0ZzG7yNessuna valutazione finora

- NadiAstrologyAndTransitspart 2Documento7 pagineNadiAstrologyAndTransitspart 2Jhon Jairo Mosquera RodasNessuna valutazione finora

- Course Outlines For CA3144 Sem A 2014-15Documento3 pagineCourse Outlines For CA3144 Sem A 2014-15kkluk913Nessuna valutazione finora

- Analytics For Sustainable BusinessDocumento6 pagineAnalytics For Sustainable BusinessDeloitte AnalyticsNessuna valutazione finora

- Fox 7th ISM ch07-13Documento1.079 pagineFox 7th ISM ch07-13Ismar GarbazzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Karatina University: University Examinations 2018/2019 ACADEMIC YEARDocumento5 pagineKaratina University: University Examinations 2018/2019 ACADEMIC YEARtimNessuna valutazione finora

- DNC / File Transfer Settings For Meldas 60/60s Series: From The Meldas ManualDocumento4 pagineDNC / File Transfer Settings For Meldas 60/60s Series: From The Meldas ManualPaulus PramudiNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit - Ii: Types of CommunicationDocumento73 pagineUnit - Ii: Types of CommunicationAustinNessuna valutazione finora

- Developing Training Program For Effective and Quality Volleyball PlayersDocumento13 pagineDeveloping Training Program For Effective and Quality Volleyball PlayersDeogracia BorresNessuna valutazione finora

- Uci Xco Me Results XDocumento4 pagineUci Xco Me Results XSimone LanciottiNessuna valutazione finora

- Brainstorming WhahahDocumento20 pagineBrainstorming WhahahJohnrey V. CuencaNessuna valutazione finora

- Senior Instrument Engineer Resume - AhammadDocumento5 pagineSenior Instrument Engineer Resume - AhammadSayed Ahammad100% (1)

- Anomaly Detection Time Series Final PDFDocumento12 pagineAnomaly Detection Time Series Final PDFgong688665Nessuna valutazione finora

- CEFR B1 Learning OutcomesDocumento13 pagineCEFR B1 Learning OutcomesPhairouse Abdul Salam100% (1)