Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Training With Purpose Strength Training Considerations For Athletes

Caricato da

Thomas Aquinas 33Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Training With Purpose Strength Training Considerations For Athletes

Caricato da

Thomas Aquinas 33Copyright:

Formati disponibili

art icle s.e lit e f t s.co m http://articles.elitefts.

co m/training-articles/training-with-purpo se-strength-training-co nsideratio ns-fo r-athletes/

Training with Purpose: Strength Training Considerations for Athletes

In the publics view, what some of us do to prepare athletes has a very small scope. T he term strength and conditioning usually brings visions of a meathead coach loading plates, spotting athletes, and screaming motivational words. However, those of us who are in the f ield know that this isnt anywhere near the truth. In reality, we program the body to respond correctly and to be prepared f or the requirements of an athletes sport. While certain sports require larger amounts of absolute strength than others, the reality is most athletes have a large amount of qualities that need to be developed with a limited amount of time to do so. Even in sports that are traditionally seen as strength related, each positional requirement can be broken down with varying levels of what can be developed through lif ting weights. T he purpose of this article is to examine some considerations when training athletes and to think of the entire process when designating intensity, volume, and exercise selection. I f irst became involved in the strength and conditioning f ield as an intern at Robert Morris University. At the time, Tom Myslinski was the head strength and conditioning coach and he worked with every sport on campus. At this point, my background was very powerlif ting inf luenced. I only knew of some things that I had read on elitef ts and they were still above my head at the time. I started this position right as practices were starting f or f ootball and incoming f reshman players were arriving. I remember being taken aback by the programming because the players werent moving massive weights in the weight room. T here wasnt any max ef f ort or dynamic ef f ort work, and there wasnt very much volume being perf ormed. I was even more conf used when some of the other sports didnt do many traditional barbell lif ts such as squats and bench presses. However, af ter learning more and starting to grasp an understanding of what was going on, I started to get the idea that a f ew things were at play. One is the f act that athletes dont only lif t weights, so the other stressors had to be accounted f or. T he second was that while many athletes may be talented at their sport, they dont necessarily have a very strong background in lif ting weights or strength training. Because of this, basic movements need to be perf ormed prior to progressing to barbell lif ting if barbell movements are even necessary f or their sport. I will say though that it took me a while af ter this to not always def ault to strength work as the end all be all. Even when interning at Pitt, I kept thinking that some of the volumes or intensities of lif ting were lower than what I had preconceived Division I players to be capable of handling in the of f season. However, considering that the work is in conjunction with sprints, jumps, medicine ball throws, and other drills that also compete f or the same central nervous system resources, it should make sense that volumes in the weight room have to be conservative. T his leads me to the next point of how many perceive what the preparation of athletes involves. Strength training f or a sport like f ootball makes people think of barbells loaded to the very ends of the collar being tossed around with players and coaches screaming motivational phrases. Of ten times, the public or even positional coaches are surprised to f ind out that some of the most skilled athletes dont have the highest levels of maximal strength in the weight room. But these athletes might also be the most skilled at their sport and have the ability to display the strength they do have in the actual competition.

I used to be one of these people who always thought about how much better an athlete might be if he could move more weight or if he was bigger and stronger. However, this doesnt take into account the qualities that the athlete needs to develop and how being able to lif t more weight maximally in the weight room may negatively af f ect other qualities. In most cases, athletes dont need to lif t maximally at high volumes to become stronger.

Int ensit y considerat ions

In the case that were talking about, the intensity of the load could be described as the percent of a maximum, a rate of perceived exertion (RPE), or a measure of physiological response. For practical purposes, most coaches will usually use a percentage or RPE scale f or this. While some sports have a need f or maximal strength, athletes dont have to work maximally in these lif ts to improve strength. When it comes to experience in weight training, many athletes arent necessarily as skilled as they are at the sport they compete in. Due to this, true maximal attempts arent usually necessary or warranted f or certain athletes. For one, they can continue to get stronger and induce other desirable adaptations through other loading protocols (higher rep work to f ocus on muscular endurance, submaximal and repeated ef f orts to f ocus on hypertrophy, etc.). Additionally, part of the training process should f ocus on motor learning. For this to occur, athletes have to become ef f icient at movements with submaximal ef f orts prior to being able to perf orm them with maximal intensities. In essence, more than one purpose can be achieved by using submaximal and repeated ef f ort loading protocols, but this may not be true of maximal attempts. T his is especially true in athletes with limited training histories who have low levels of strength. By having them work up to a maximal attempt, they wont really have a ton of volume when you perf orm the max. Contrast this with working submaximal weights and having more total work perf ormed where the total volume will be higher.

Now, I know a f ew people will play devils advocate and say Well, both you and I agree that athletes arent lif ters, so why should the f orm be perf ect? While I understand that athletes arent lif ters, the point here is that maximal attempts with bad f orm can open athletes up to injury. While I know that this may happen every once in a while when attempting a true max, it shouldnt happen all the time. Also, the minority of training would be perf ormed at true maximal intensities and coaches can always decide when to shut a player down. T his could be done when technical f laws are beginning to surf ace as opposed to a true max. Another consideration is the other stressors in the training load including sprints, jumps, throws, drills, and depending on the time of the year, practices. T here will always be some give or take in this area. Central nervous system intensive activity such as sprinting has a strong neurological ef f ect and athletes are able to produce a high amount of f orce in these types of movements. T his doesnt necessarily mean that high intensity strength training cant be perf ormed, but it may not be needed on a consistent basis. Also, in ref erence to lower body training, sprint and jump training provide a high intensity stimulus to the lower body in which true maximal strength work may not be necessary or may end up being counterproductive to the training process as a whole in sports that are alactic/aerobic. T he last consideration is the amount of maximal strength necessary. For certain sports, there isnt a need to display any great amount of f orce against large, external resistances. For these sports or positions, a greater level of explosive strength and high speed strength is of importance, which may not be developed by lif ting heavy weights slowly. For other sports, there isnt any need to display great amounts of f orce at any point. In this case, true maximal strength training may be a waste of time f or the athlete. While this seems like it should be common sense, there are some coaches or trainers out there who probably would have a racewalker (that weird sport in the Olympics where theyre penalized f or moving too quickly) perf orming maximal ef f ort work week in and week out and talking about the virtues of training the central nervous system when in reality it has no real carryover to the sport.

Volume considerat ions

For an athlete who doesnt compete in a strength sport, volume in the weight room will always be inf luenced by what other components are being trained. T here isnt going to be a chart, program, set/rep scheme, or any other absolute when determining how much work an athlete should perf orm in the weight room. T he only absolute should be a consideration of the total amount of work. Keep in mind that adaptive reserves are f inite. Again, going back to an example of this, someone may look at a weight room workout on paper, see that there may only be one or two strength exercises being perf ormed, and think that it doesnt seem like very much volume. Many who look at programs with a lif ters mind may think that the athlete couldnt possibly get stronger. However, all high central nervous system intensive activity that may have been perf ormed on that day and that will be perf ormed later in the weekneeds to be considered. Because of this, there may not be a whole lot of time to include a f ull-f ledged lif ting workout. When looking at the amount of sprints, jumps, throws, f ull speed drills, and similar exercises, it becomes apparent that there is only so much lif ting that can be included. As f ar as how much volume is too much or too little, this is something that cant be decided by any one chart or source. Prilipens chart has been an old standby, but we need to consider that this was based on junior Olympic lif ters who werent necessarily practicing a sport, running, or jumping. Because of this, many times f ewer lif ts should be included in a workout than what is listed as optimal. While you can start with a high amount of volume and roll the dice as f ar as recovery and adaptation, it is a f ar smarter idea to be conservative and possibly low ball the volume of strength work to allow room f or progress. For an athlete who doesnt lif t as a sport, the weight room will always be only a component of becoming better. Will there be times when maximal strength may have an emphasis over other qualities? It really depends on the sport. We could take a sport like f ootball, which is traditionally viewed as having a need f or high levels of maximal strength. However, if we break down the sport by position, its easy to see that certain positions such as of f ensive and def ensive linemen will have a greater need f or maximal strength than their skill player counterparts. However, even in this case, it really doesnt matter how much weight they can squat, bench, or clean if theyre unskilled at the sport, constantly injured, unable to move, and so on. Even f or the players who need a level of strength, they also have to f ocus on a variety of other motor abilities. T hey might be able to lif t the house in the weight room, but this doesnt mean that they will be able to display this on the f ield. T here may be times of the year when slightly higher volumes of strength work are being perf ormed, but the strength coach should consider whether or not high volumes of weight room work are redundant or counterproductive. For athletes who engage in true sprint work at maximum velocity with appreciable volumes, large amounts of direct hamstring work may have a negative ef f ect on the ability to sprint or lead to sof t tissue injuries. In this case, the hamstrings are already being taxed to a great degree in the top speed work, so f urther taxing them with intense loading may be too much structurally. T his is one of the instances where it is important to f ocus on what not to do instead of attempting to do too much.

Exercise select ion considerat ions

When working with athletes, we need to consider the actual exercises that were choosing. Choose movements that actually contribute to what the athlete needs to do in his sport and dont f ocus on what they dont need. With athletes, our main goal is to strengthen what will contribute to them reaching higher sports results. Far too of ten, we see coaches having a hard on f or certain exercises or the perf ormance of certain exercises. One that comes to mind is squat depth. Some are obsessed with ass to grass or f ull squatting. However, if we look at most sports, regardless of position, it isnt a requirement or a necessity f or an athlete to squat that deep. I know this f rom my own experience, as I used to require all my athletes to squat to what is parallel by powerlif ting standards. However, f or most athletes, the depth of a half squat (90 degree f lexion of the knee) is as f ar as they need to go. T his applies to any lif t including Olympic lif ts and powerlif ting variations. Some movements are pretty much expendable, such as all general barbell, dumbbell, and machine exercises. If an athlete isnt capable of perf orming an exercise ef f iciently or saf ely and it isnt of great importance to his sport, consider whether or not the athlete can perf orm another movement that accomplishes the same thing. Something I learned f rom Buddy Morris while interning at Pitt is, Give them things they wont f uck up. T his is why arguments over Olympic lif ting versus powerlif ting versus Strongman are irrelevant. T here shouldnt be any blind allegiance to any one exercise because a large amount of weight room exercises are nothing more than general f or the athlete. We need to examine what is possible, usef ul, and appropriate f or the needs of the athlete. I know someone has gotten his panties in a wad and will probably say that having athletes squat high will leave them tight, immobile messes and that this is doing a massive disservice to them. However, lets not f orget that things such as mobility and f lexibility should be addressed through other areas of the training process. If dynamic warm ups, supportive exercises with greater ranges of motion, and prehabilitation are perf ormed, it is unnecessary to think that every movement perf ormed needs to be through the greatest range of motion possible. T his is reminiscent of those who think that overhead pressing is necessary because athletes will need to place their arms overhead to reach f or a ball but f orget that this is unloaded.

Many of these general weight room exercises arent always f orgiving to a large number of dif f erent leverages. Certain long-limbed individuals will be at a disadvantage f or movements like squats and benches. Others may be built in ways that arent best suited f or pulling or whatever other general exercise we want to consider. T his is why the main consideration needs to be the training ef f ect. As f ar as movements, at times, its best to just write in generalities because being stuck to one particular exercise may be an inef f icient use of time. Movements like sprints, jumps, medicine ball throws, and even specialized exercises may be more f orgiving to a certain population of athletes. In a question on the Q&A that I had to the T hinker a while back in ref erence to exercise selection, he stated that movement ef f iciency is the ultimate qualif ier f ollowed by selecting the loading parameters f or the desired training ef f ect that will still allow proper execution.

Put t ing it all t oget her

When deciding on intensity, volume, and exercise selection f or athletes, the f ollowing questions should be considered: 1. What type of strength is required for the athlete in his sport? Its important to look at the individual athlete, not the sport. Dif f erent positions have dif f erent needs. While certain sports may need a certain level of maximal strength, each position may have dif f erent requirements. In certain positions, maximal strength may only act as a base f or the development of more important qualities like explosive strength or high speed strength. For other sports, maximal strength development may not be needed and it may be a waste of time to develop it to any great extent. 2. How many other stressors are being imposed on the athlete at the current time?

Remember that there is a time and a place to have a greater amount of work in the weight room. At other times, the weight room may have to take a back seat to other stressors that are at higher volumes. In the of f season, sprints or more specialized work f or the athletes sport may be the f ocal point. Weight room work will have to be conservative in either intensity or volume. At other times of the year, practice and competition may be the greatest stressor to take into account. Weight room work will be a supportive role and possibly may need to be regulated down a good bit to maintain perf ormance in the sport itself . 3. What is the desired training effect, and what is necessary to reach this effect? Draw up a list of movements that can help reach this goal. Def ine loading parameters f or each that will be directed toward the desired training ef f ect. Also, throw out whatever movements arent necessary and narrow down the list. 4. Of the movements listed, which ones are possible, useful, or appropriate for the athlete? While certain movements may be of use to the athlete, they may either not be possible due to injury or structural limitation or they might not be appropriate due to other prerequisites f or perf ormance. At this point, the list can be narrowed down f urther and choices that f it all three of the criteria can be made.

Conclusion

As coaches, it is important f or us to remember that the athletes we train arent powerlif ters, Olympic lif ters, or strongman. T hey are trying to develop skills in a sport that has its own set of perf ormance guidelines. Strength is only one of the motor abilities they may or may not need to be successf ul. T he weight room is only one tool that may be used to develop the various types of strength they need. Proper execution of exercise and loading parameters that reach the desired training ef f ect should always be considerations when programming f or athletes. Ill admit that Im a guy who in the past has def aulted to the weight room. While I like strength as much as the next person, it cant be the f ocal point at all times. Whatever is deemed possible, usef ul, and appropriate f or the athlete in relation to the end goal of the training process is what has to be considered. While some of the exercise selection can end up being dry or boring, it is all about perf ormance in the event or game that matters f or the athlete. Everything else is just one piece of the puzzle.

Related Articles

Training with Purpose: Programming T houghts and Considerations for the New Year Training with Purpose: Rebuilding Training with Purpose: Individualization

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Pre Algebra HandbookDocumento107 paginePre Algebra HandbookThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ethics 2 Says, "Happiness (Felicitas) Is The Reward of Virtue." But Intellectual Habits Do Not Pay AttentionDocumento9 pagineEthics 2 Says, "Happiness (Felicitas) Is The Reward of Virtue." But Intellectual Habits Do Not Pay AttentionThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Education of A Tactical Meathead Getting Jacked and Making Money Part 1Documento10 pagineThe Education of A Tactical Meathead Getting Jacked and Making Money Part 1Thomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- By The Coach For The Coach The Ladies Take OverDocumento9 pagineBy The Coach For The Coach The Ladies Take OverThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- LATINA MI Secundus DiçsDocumento2 pagineLATINA MI Secundus DiçsThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Are You Training Too HeavyDocumento5 pagineAre You Training Too HeavyThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sacrament of Initiation and PenanceDocumento44 pagineSacrament of Initiation and PenanceThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly 528Documento5 pagineAmerican Catholic Philosophical Quarterly 528Thomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mcinery Prudence and ConscienceDocumento11 pagineMcinery Prudence and ConscienceThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Set and Rep Schemes in Strength Training Part 1Documento7 pagineSet and Rep Schemes in Strength Training Part 1Thomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ive Got 99 Problems But My Shoulder Aint OneDocumento3 pagineIve Got 99 Problems But My Shoulder Aint OneThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Keep It Simple Stupid Part 2 Assistance WorkDocumento4 pagineKeep It Simple Stupid Part 2 Assistance WorkThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reignite Progress With New ScienceDocumento13 pagineReignite Progress With New ScienceThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Kentucky Strong Add 100 Pounds To Your PullDocumento12 pagineKentucky Strong Add 100 Pounds To Your PullThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Training With Purpose Programming Thoughts and Considerations For The New YearDocumento5 pagineTraining With Purpose Programming Thoughts and Considerations For The New YearThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Flexible Periodization Method Out of Sight Out of Mind Part 3Documento4 pagineThe Flexible Periodization Method Out of Sight Out of Mind Part 3Thomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Training With Purpose IndividualizationDocumento6 pagineTraining With Purpose IndividualizationThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Speed Vs SpeedstrengthDocumento4 pagineSpeed Vs SpeedstrengthThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Coach G What Is Your Philosophy Part 2 PDFDocumento11 pagineCoach G What Is Your Philosophy Part 2 PDFThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Developing Your Own Training Philosophy PDFDocumento5 pagineDeveloping Your Own Training Philosophy PDFThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- My Return To PowerliftingDocumento8 pagineMy Return To PowerliftingThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Monster Garage Gym Its Not Always The Strongest Lifter Who Wins PDFDocumento9 pagineMonster Garage Gym Its Not Always The Strongest Lifter Who Wins PDFThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- High Powered JournalingDocumento6 pagineHigh Powered JournalingThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- OffSeason Football Training For The NFL Working With Defensive Players From The Oakland Raiders PDFDocumento3 pagineOffSeason Football Training For The NFL Working With Defensive Players From The Oakland Raiders PDFThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Flexible Periodization Method Program Design With Kettlebells Part 2Documento7 pagineThe Flexible Periodization Method Program Design With Kettlebells Part 2Thomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Training With Purpose Deep Love or Cheap LustDocumento5 pagineTraining With Purpose Deep Love or Cheap LustThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Developing Your Own Training PhilosophyDocumento5 pagineDeveloping Your Own Training PhilosophyThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Facts Needed To Prevent Hamstring StrainsDocumento4 pagineFacts Needed To Prevent Hamstring StrainsThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- Elitefts Classic Training The Bench Press by Jim WendlerDocumento5 pagineElitefts Classic Training The Bench Press by Jim WendlerThomas Aquinas 33Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Multiplication of Decimals: For Mathematics Grade 5 Quarter 2 / Week 3Documento24 pagineMultiplication of Decimals: For Mathematics Grade 5 Quarter 2 / Week 3Mr. BatesNessuna valutazione finora

- Admit Card 2019-20 Odd-SemDocumento2 pagineAdmit Card 2019-20 Odd-SemVIKASH KUMARNessuna valutazione finora

- Importance of Interpersonal Relationship: An Individual Cannot Work or Play Alone Neither Can He Spend His Life AloneDocumento2 pagineImportance of Interpersonal Relationship: An Individual Cannot Work or Play Alone Neither Can He Spend His Life AlonenavneetNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic Act No. 10029Documento12 pagineRepublic Act No. 10029Mowna Tamayo100% (1)

- Address:: Name: Akshita KukrejaDocumento2 pagineAddress:: Name: Akshita KukrejaHarbrinder GurmNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity Design For Career Week CelebrationDocumento4 pagineActivity Design For Career Week CelebrationLynie Sayman BanhaoNessuna valutazione finora

- List of Most Visited Art Museums in The World PDFDocumento15 pagineList of Most Visited Art Museums in The World PDFashu548836Nessuna valutazione finora

- Answer Sheet - For PMP Mock 180 QuestionsDocumento1 paginaAnswer Sheet - For PMP Mock 180 QuestionsAngel BrightNessuna valutazione finora

- Mark Scheme (Results) : January 2018Documento11 pagineMark Scheme (Results) : January 2018Umarul FarooqueNessuna valutazione finora

- Kawar Pal Singh Flinders Statement of PurposeDocumento5 pagineKawar Pal Singh Flinders Statement of Purposeneha bholaNessuna valutazione finora

- 10.2 Friendships in Fiction and Power of PersuasionDocumento6 pagine10.2 Friendships in Fiction and Power of PersuasionMarilu Velazquez MartinezNessuna valutazione finora

- CSEC POA CoverSheetForESBA FillableDocumento1 paginaCSEC POA CoverSheetForESBA FillableRushayNessuna valutazione finora

- Berlitz Profile 2017Documento15 pagineBerlitz Profile 2017Dodi CrossandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Developmental Characteristics of 6th GradersDocumento52 pagineDevelopmental Characteristics of 6th GradersDalen Bayogbog100% (1)

- ID Model Construction and Validation: A Multiple Intelligences CaseDocumento22 pagineID Model Construction and Validation: A Multiple Intelligences CaseFadil FirdianNessuna valutazione finora

- f01 Training Activity MatrixDocumento2 paginef01 Training Activity MatrixEmmer100% (1)

- Podar Education Presentation 2020Documento14 paginePodar Education Presentation 2020MohitNessuna valutazione finora

- LESSON PLAN Friends Global 10 - Unit 6 ListeningDocumento5 pagineLESSON PLAN Friends Global 10 - Unit 6 ListeningLinh PhạmNessuna valutazione finora

- Apply To Chevening 2024-25 FinalDocumento19 pagineApply To Chevening 2024-25 FinalSaeNessuna valutazione finora

- Certificte of Participation Research Feb.17 2022Documento14 pagineCertificte of Participation Research Feb.17 2022Janelle ExDhie100% (1)

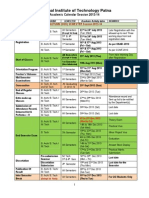

- Nit Patna Academic CalendarDocumento3 pagineNit Patna Academic CalendarAnurag BaidyanathNessuna valutazione finora

- Thời gian: 150 phút (không kể thời gian giao đề)Documento9 pagineThời gian: 150 phút (không kể thời gian giao đề)Hằng NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- Lucknow Public Schools & CollegesDocumento1 paginaLucknow Public Schools & CollegesAຮђu†oຮђ YสdสvNessuna valutazione finora

- Developing The Cambridge LearnerDocumento122 pagineDeveloping The Cambridge LearnerNonjabuloNessuna valutazione finora

- Ej 1165903Documento15 pagineEj 1165903Christine Capin BaniNessuna valutazione finora

- ResumeDocumento4 pagineResumeJacquelyn SamillanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Mafikeng Study Info - Zfold - Web - 1-1 PDFDocumento2 pagineMafikeng Study Info - Zfold - Web - 1-1 PDFNancy0% (1)

- USC University Place Campus MapDocumento2 pagineUSC University Place Campus MapTaylor LNessuna valutazione finora

- VM Foundation scholarship applicationDocumento3 pagineVM Foundation scholarship applicationRenesha AtkinsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 2: Language Test B: GrammarDocumento2 pagineUnit 2: Language Test B: GrammarBelen GarciaNessuna valutazione finora