Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

"Why There?" Islamophobia, Environmental Conflict, and Justice at Ground Zero - Patrick Sweeney and Susan Opotow

Caricato da

Patrick SweeneyTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

"Why There?" Islamophobia, Environmental Conflict, and Justice at Ground Zero - Patrick Sweeney and Susan Opotow

Caricato da

Patrick SweeneyCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Why There?

Islamophobia, Environmental Conflict, and Justice at Ground Zero Patrick Sweeney & Susan Opotow

Social Justice Research ISSN 0885-7466 Soc Just Res DOI 10.1007/s11211-013-0199-6

1 23

Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media New York. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be selfarchived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com.

1 23

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res DOI 10.1007/s11211-013-0199-6

Why There? Islamophobia, Environmental Conict, and Justice at Ground Zero

Patrick Sweeney Susan Opotow

Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013

Abstract Conicts over environmental spaces that are sites of trauma or have been designated as sacred involve questions about who has a legitimate stake in determining the use of the site, and where the hallowedness attached to that space ends. We examine these questions in a study of the 20092010 controversy about the Park51 [sic] Islamic Community Center, sometimes called the Ground Zero Mosque, to examine how issues of distributive, procedural, and inclusionary justice play out in a conict over valuable land close to Ground Zero. This conict, though in a specically fraught locale, speaks to resistance to mosque construction in the USA and Europe. Using newspaper articles on the public debate as data (N = 65), and performing a thematic analysis, we identied four key themes: (1) views of Islam, (2) conict, (3) American identity and ideals, and (4) proximity and place. Utilizing Chi square analyses to examine the effect of propinquity on support for Park51, we found that people living within New York City were more likely to support Park51 than those outside of the city. Our conclusion discusses constructs that link values, space, and social relationshallowed ground, place attachment, social distanceand discuss their relationship to justice. We argue that while several kinds of justice are relevant, at its heart, this conict concerns inclusionary questions about who can speak, who belongs, and who should be excluded. Keywords Environmental conict Distributive justice Procedural justice Inclusionary justice Islamophobia Ground zero

P. Sweeney (&) The Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA e-mail: psweeney@gc.cuny.edu S. Opotow John Jay College of Criminal Justice and The Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

Introduction On May 5, 2010, a community board meeting in Lower Manhattan that might normally have been uneventful was the site of fractious controversy. A raucous four hour hearing (Hernandez, 2010, p. A23) culminated in the approval of a proposal to build an Islamic community center near Ground Zero. The heated exchange concerning two adjacent buildings lasted 9 months. This conict offers valuable details about the intersection of justice and the environment in a unique context, a site of historic and symbolic importance where World Trade Center Towers 1 and 2 stood from 1973 until they were destroyed in the September 11, 2001 (9/11) attacks. This site of conict reveals interconnections among 9/11, Islamophobia, and the distribution of scarce spatial resources in Lower Manhattan. Environmental conicts over sites of memory or trauma surface questions about who has a legitimate stake in determining the use of that site, and where the hallowedness attached to that site ends. Focusing on justice issues within this conict, particularly procedural, distributive, and inclusionary justice, this paper presents an analysis of this conict as it was reported in New York Times articles (N = 65) published from December 9, 2009 to September 21, 2010. These data reveal that environmental and justice issues entwine in questions about the boundaries of and values attached to a highly charged site that has been deemed sacred. Environment as the Context of Conict Environment is both the contexts in which we live and all social relations occur, as well as a social issue in its own right (Opotow & Gieseking, 2011). It is a construct with broad meaning, encompassing micro to macro contexts and built, natural, and socialenvironments. Conict exists whenever incompatible activities occur, particularly activities that will prevent, obstruct, interfere with, injure, or in some way make another action less likely or less effective (Deutsch, 1969). Conict occurs within and about particular environments. Here we study conict about the use of a particular environmentthe area near Ground Zero in Lower Manhattan. The conict over the site near Ground Zero is similar to other land-use conicts which link social identities and meanings to specic geographic locales, generating community dialogs about land-use decisions that can vary in intensity (WesterHerber, 2004; Harwood, 2005). In recent years, conicts over land-use in the United States of America (USA) and Europe have ared over the construction of mosques (Cesari, 2005). In addition to its practical function of providing Muslims with a space for religious services and community activities, the construction of a mosque has importance as a symbolic activity because it embodies the inclusion of Muslims in the public sphere (Sunier, 2005). Resistance to new mosques is often supported by meta-narratives in which Islam is systematically conated with threats to international or domestic order (Cesari, 2005, p. 1019). Issues of national identity and questions of who belongs and who does notplay out in debates about appropriate use of space (Triandafyllidou & Gropas, 2009). Conicts about the construction of mosques in

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

the USA, from Long Island in New York State to Temecula in California have invoked similar issues of inclusion. These conicts are a rich source of data on how justice is debated within a specic environmental context. Justice and Environmental Conict Conicts concerning the construction of mosques can be productively studied from a justice perspective, because justice is at issue when there is a problem of competing claims on a resource (Leventhal, 1979; Coser, 1956). Indeed, conicts are contexts in which concerns for justice emerge (Deutsch, 1985; Opotow, 1990). In environmental conict, justice issues that emerge include the distribution of physical and social resources, the role of values in decision-making, conict management, and the inclusion or exclusion of marginalized groups and perspectives (Opotow & Clayton, 1994; Opotow & Weiss, 2000). We primarily focus on three key lines of psychological research on justice: distributive justice, procedural justice, and inclusionary justice (Opotow, 1997; Clayton & Opotow, 2003). Briey, distributive justice concerns the allocation of physical and social resources. It focuses on the fair distribution of such concrete resources as land and elements of the built environment as well as such socially valued resources as social status and rights (Deutsch, 1985; Foa & Foa, 1974). Procedural justice concerns the fair application of procedures and rules to groups across time, including having a voice in processes, the respectful treatment of those involved, and management of conict (Lind & Tyler, 1988; Thibaut & Walker, 1975). Inclusion in the scope of justice concerns whether prevailing values, rules, and norms apply. Groups that are marginalized or seen as outside the scope of justice may be seen as undeserving of resources or fair treatment. Their material or psychological wellbeing may then be seen as irrelevant and, instead, harm they experience may be condoned (Opotow, 1995). Park51: The Ground Zero Mosque An article about the proposed Park51 Islamic Community Center (Park51) published on the front page of the New York Times in December 2009, 5 months before the furor that erupted at the community board on May 5, 2010, hinted at the conict to come. It noted that a supporter of Park51, Joan Brown Campbell, interfaith leader and former general secretary of the National Council of Churches of Christ USA, acknowledged the possibility of a backlash from those opposed to a Muslim presence at Ground Zero (Blumenthal & Mowjood, 2009, p. A1). Indeed, Blumenthal and Mowjoods (2009) New York Times article marked the beginning of a spirited and, at times, mean-spirited debate about the meaning of 9/11, Islam, and the Park51 Islamic Community Center. The article described the proposed building as unexpected, striking, and bold (p. A1), while the rebuilding of a Christian church in a nearby locale, even closer to Ground Zero, was portrayed as expected, appropriate, and banal (Vitello, 2010, p. A16). While the center became known to many as the Ground Zero Mosque (Barnard, 2011), it is

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

Fig. 1 Photograph of 4551 Park Place, Photo: Susan Opotow

neither at Ground Zero nor is it technically a mosque. We use its ofcial name, Park51, in this paper. Throughout the conict, three key organizers of Park51 served as its public face: Feisal Abdul Rauf, the imam of a mosque nearby; Daisy Khan, Raufs wife and an interfaith organizer; and Sharif El-Gamal, a real-estate developer. All three were featured in and scrutinized by the media and held up as emblematic of what it means to be Muslim in America. As conict intensied, the appropriateness of the center for a site near Ground Zero became front page news. For its supporters, Park51 was a symbol of all that is right with Islam; for those opposed, Park51 was a symbol of the dangers of Islam (Fig. 1). Building Site: Geographic and Social Terrain of the Conict Park51 was planned as an interfaith community center open to all New Yorkers, regardless of religion, modeled on the 92nd Street Y, a nonprot cultural and community center in New York City. Park51s planners wanted its 13 stories to rise two blocks from the pit of dust and cranes where the twin towers once stood, a symbol of the resilience of the American melting pot (Hernandez, 2010, p. A22). They envisioned a building with two oors for Muslim prayer space. Other oors would house a 500-seat auditorium, a theater, a performing arts center, a tness center, a swimming pool, a basketball court, a child care center, an art gallery, a bookstore, a culinary school, and a restaurant. As Low and Altman (1992) argue, the meanings and ideas attached to a place inform the norms, rules, and regulations that govern how a particular site is used. The story of the buildings shuttering due to the events of 9/11 contributed to creating the background of cultural memories that were drawn upon by those debating the future of the space. At this site, there are two adjacent buildings located

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

at 4547 Park Place and 4951 Park Place between Church Street and West Broadway. The neighborhood, Lower Manhattan, is New York Citys center for business and government. This site is just north of an area that was called Little Syria in the rst half of the twentieth century when the neighborhood around Washington Street in Lower Manhattan was the heart of New Yorks Arab worldMuslims, chiey from Palestine, made up perhaps 5 percent of its population. The Syrians and Lebanese in the neighborhood were mostly Christian (Dunlap, 2010, p. A16). A church that served many from this Arab population, Saint George Chapel of the Melkite Rite, still stands nearby at 103 Washington Street. 4951 Park Place is a former substation of the privately owned energy company, Con Edison, which supplies electric, gas, and steam service in NYC. The adjacent building, 4547 Park Place, is a ve-story building designed by Daniel Badger in the Italian Renaissance Palazzo style in 18571858 and built for a shipping rm (Geminder, 2010). In 1968, after the Arab-American community was almost entirely displaced by construction of entrance ramps to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel (Dunlap, 2010, p. A16), the building at 4547 Park Place was bought by discount clothing retailer Sy Syms, becoming an early Syms store. When Syms closed in 1990, the building was leased to the Burlington Coat Factory. This Burlington Coat Factory store closed just after 9/11/01 when out of a baby-blue sky suddenly stained with smoke, a planes landing-gear assembly the size of a World War II torpedo crashed through the roof and down through two empty selling oors (Blumenthal & Mowjood, 2009, p. A1). Since then, 4547 had stood empty, but in July 2009 it was sold to a real estate investment rm headed by Sharif ElGamal. To forestall the planned demolition of 4547 Park Place to build the center, anti-Park51 activists noted the buildings Italian Renaissance style architecture in a complaint to the Landmarks Preservation Commission. The Commission did not nd the buildings architectural details signicant enough to warrant landmark status and voted 90 to deny historic protection to the building (Barbaro & Hernandez, 2010). Beyond the meanings attached to the neighborhood surrounding the buildings at 4547 and 4951 Park Place, this conict also occurred within the hostile sociopolitical terrain of post 9/11 Islamophobia in the United States. Islamophobia is a term that came into use in Europe and USA in the early 1990s and is dened as indiscriminate negative attitudes or emotions directed at Islam or Muslims (Bleich, 2011, p. 1585). In addition to attitudes and emotions, Islamophobia can manifest behaviorally. In the USA after 9/11, Islamophobia has manifested itself in an unrelenting, multivalent assault on the bodies, psyches, and rights of Arab, Muslim, and South Asian immigrants that has included restrictions on immigration of young men from Muslim countries, racial proling and detention of Muslim-looking individuals, and an epidemic of hate violence against Arab, Muslim, and South Asian communities (Ahmad, 2002, p. 101). Hate crimes against Muslims in the USA increased by 1,700 % in the year after 9/11, and antiMuslim attitudes, while relatively understudied in psychology, appear to have increased following 9/11 (Khan & Ecklund, 2012; Sheridan, 2006). Media representations of Islam in the USA after 9/11 have been overwhelmingly negative and often linked to terrorism (Bilici, 2005). Given the ferocity of Islamophobic

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

sentiment in the USA, psychological researchers have urged that Islamophobia must be taken into account when designing studies concerning Muslim Americans, and furthermore declared that psychologists have an ethical responsibility to combat Islamophobia (Amer & Bagasra, 2013). Our study conceptualizes Islamophobia as part of the sociopolitical environment in which the current conict occurred.

Method: Public Debate in the News To examine the relationship between environment as embodied in this site and justice as a contested construct, we examine newspaper articles as records of conict about this controversy. Our data consist of 65 articles, opinions, and editorials published in the New York Times that discuss Park51 from December 9, 2009 to September 21, 2010. Newspapers as Sources of Data Newspapers are an important data source because of their in-depth coverage of events, actions, and activities across contexts and over time. They set the agenda for public discourse and shape collective representations of contemporary issues (Nafstad & Blakar, 2012). The selection of events covered by newspapers and the way in which these events are presented raise questions about bias and validity (Barranco & Wisler, 1999; Earl, Martin, McCarthy, & Soule, 2004; Ortiz, Myers, Walls, & Diaz, 2005). Nevertheless, newspapers are an unparalleled source of information because they offer reports of events as they occur. They also inuence the public discourse as they are a source of information that can stimulate interest in and shape opinion about contemporary events and social issues. Although more commonly used in research in communication studies, political science, and sociology, psychological research draws on newspapers as data, particularly for studies of attitude change. Nafstad and Blakar (2012) conduct longitudinal analyses of changes in language usage in newspapers to trace how neoliberal individualist ideologies can obscure injustice. By studying word frequency alongside contextual analyses of language usage, their approach is an unobtrusive way to examine the creation and legitimation of ideology. Geschke, Sassenberg, Ruhrmann, and Sommer (2010) examine how media coverage affects attitudes toward social groups based on what and how events are reported. Their scholarship analyzes the effects of bias present in content as well as in the rhetorical style of newspaper articles (e.g., form, tone) written about migrants. Stewart, Pitts, and Osborne (2011) study the construction of the concept of the illegal immigrant in public discourse by examining descriptions of undocumented immigrants across a set of newspaper articles. We use newspaper articles to investigate how issues of justice and environment intersect in the public discourse surrounding the Park51 conict. The New York Times offers unparalleled access to the conict surrounding Park51. A newspaper of record, The New York Times meets especially high journalistic standards, is internationally renowned, and inuential (Salles, 2010; Martin & Hansen, 1998). Because Park51 is located within the city in which The New York Times

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

is published, this newspaper offers unequaled coverage of the conict in detailed articles. During the 10 months of our study period, the height of the conict, 14 different journalists reported offering an overarching institutional viewpoint. Data and Analysis To study the Park51 controversy, we conducted a Lexis Nexis search of the New York Times using the descriptors Mosque OR Muslim OR Islam AND Ground Zero OR 9/11. This generated 239 results that included articles not pertinent to the conict (e.g., unrelated election coverage, general discussions of Islam or 9/11). Eliminating duplicate articles and those unrelated to this controversy resulted in a nal sample of 65 articles, op-eds, and letters to the editor. This sample was checked for completeness by searching The New York Times website using the same descriptors and also by checking our sample against the Times Topic page for Park51 which collects all articles on that topic. These checks indicated that we had identied all relevant articles on the Park51 controversy within the 10-month period in which the conict was most intense. To identify the key themes in the 65 newspaper articles on this conict, we used a random number generator to sample ten articles throughout the time period of interest. We read through each, marking key themes, comparing our ndings, and resolving inconsistencies. We repeated this process four times. We next compared the themes for each of the four random samples. We found four themes recurring in more than one sample and we used them to analyze the entire set of 65 articles, allowing each article to be coded with at least one and up to four themes. After presenting our ndings on the four themes, we describe a quantitative analysis that emerged from the data found on the relationship between proximity to Ground Zero and support for Park51 (Table 1).

Results: The Park51 Controversy in the News Our analysis of 65 articles in The New York Times yielded four key themes: (1) views of Islam, (2) conict, (3) American identity and ideals, and (4) proximity and

Table 1 Key article themes Number of articles Theme 1: Views of Islam Theme 2: Conict Theme 3: American Identity and Ideals Theme 4: Place 44 39 38 18 Percent of articles containing theme (%) 68 60 58 28 Examples of topics

Headscarves, terrorism, suspicion, radicalism Fear, interfaith, compromise, anger Religious freedom, civil rights, citizenship Proximity, hallowed ground, delement, public space

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

Fig. 2 Anti-Park51 advertisement created by the American Freedom Defense Initiative

place. Each of our articles contained one or more of these themes, with an average of 2.14; only three included all four themes. In this section we describe each theme and, using one article to illustrate it, discuss its relevance in this conict. The details in the examples illustrate how the theme played out in the Park51 controversy as well as how it is entwined with the other themes. Theme 1: Views of Islam Views of Islam, the most prevalent theme, was present in 44 of the 65 articles which mentioned: terrorism, headscarves, Muslims, barbaric images, religious extremism, collective guilt, meaning of Islam, jihad, radicalism, and suspicion. They reported on competing views of Islam and debated the meaning of Islams true character from the perspective of adherents and non-Muslims. Some of the speakers in these articles positioned Islam as an inherently peaceful religion, while others positioned it as an ideology linked to terrorism and violence. These articles centered around a variety of ashpoints for conict, incidents within the larger controversy that exposed underlying views about Islam through debates over particular issues. Dispute Over Ad Opposing Islamic Center Highlights Limits of the MTAs Powers (Grynbaum, 2010), a New York Times article published on August 12, 2010 exemplies the theme, Views of Islam. This article describes a controversy over an advertisement (Fig. 2) submitted to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) for display on New York City MTA buses. It goes on to describe the MTAs history of rejecting obscene or deceptive advertisements, issues of Islamophobia, radicalism, and the relation of Islam to 9/11. The conict emerged from an advertisement submitted to the MTA by the American Freedom Defense Initiative, a national group vehemently opposed to Park51. Their colorful advertisement consists of a horizontal rectangle featuring a large headline asking WHY THERE? (capitalized). On the left side of the advertisement is an image of the World Trade Center with an airplane about to strike one tower while the other tower is engulfed in ames. On the right side is an image of a building, presumably Park51, emblazoned with a star and crescent. A double-sided arrow near the bottom of the ad links the two buildings. Next to the image on the left are the capitalized words SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 WTC JIHAD ATTACK, and accompanying the image on the right are the words SEPTEMBER 11, 2011 WTC MEGA MOSQUE. Centered and below are the words GROUND ZERO, set in capitalized red text with a yellow border, with a background of black smoke.

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

The article describes the controversy that ensued when the MTA initially rejected the advertisement as unsuitable, repeatedly requesting changes to the photograph of the twin towers (Grynbaum, 2010, p. A22). In response, a federal lawsuit was led by the group sponsoring the advertisement and its leader, the prominent right-wing blogger Pamela Geller, who argued that her right to free speech had been infringed (Grynbaum, 2010, p. A22). The group, which has repeatedly provoked controversy, was already involved in a lawsuit against transit ofcials in Detroit who had rejected a bus advertisement aimed at converting Muslims, an ad that has already appeared on New York City buses. The Why there? advertisement ultimately was displayed on city buses, but it was widely regarded as inappropriate. New York Citys then public advocate, Bill de Blasio, stated that This ad crosses a line, and I cant believe the MTA would allow it on its buses (Grynbaum, 2010, p. A22). This article situates the intersection of the environment and justice in three nested conicts: the presenting conict is within a municipal agency, the MTA, charged with deciding what forms of speech are appropriate. A larger conict is whether Park51 belongs in its proposed site. At its root, the conict is about the nature of Islam and its place in the USA. The conict over the advertisement is a site in which issues of inclusionary justice are played out in a particular environment. Theme 2: Conict The Conict theme, the second most prevalent in our sample, was present in 39 of the 65 articles. It emerged in mentions of constructive and destructive processes and outcomes of conict (Deutsch, 1973). Constructive processes and outcomes include: consensus, compromise, interfaith cooperation, debate, forgiveness, cross-cultural sensitivity, and how some groups have worked together to nd solutions to their differences. Destructive conict processes and outcomes include: culture war, anger, lies, misrepresentations, opportunism, Holocaust metaphors, hate crimes, disgust, fear, and how groups clashed over Park51. Planned Sign of Tolerance Bringing Division Instead (Hernandez, 2010), published in The New York Times on July 14, 2010, exemplies the theme, Conict. Most articles in our sample cover conict. We chose this one because it discusses the deeply emotional nature of the Park51 conict, the various groups involved, and the expression of conict at multiple levels (e.g., local governance to national politics). This article characterizes the Park51 controversy as full of deep divisions marked by vitriolic commentary, pitting Muslims against Christians, Tea Partiers against staunch liberals, and Sept. 11 families against one another (Hernandez, 2010, p. A22). The article reports on a hearing conducted by the citys Landmarks Preservation Commission to decide whether or not to grant protected landmark status to the building at 4547 Park Place, a hearing with bellicose discourseon full display (p. A22). The article describes background of the conict using words charged with tension: sacrilege, fury, vigorous opposition, offense, intensity, hostility, and vitriolic (p. A22), evoking the deep meaning that the Park51 site has for many individuals and groups regardless of whether they support or oppose Park51.

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

The article features quotations from members of two families. Each mourns a relative who died on 9/11, and each has a different viewpoint on the proposed center. These quotes mirror larger patterns of discourses seen across the body of articles that contrast those for and against Park51. A family member on one side says that the center would constitute sacrilege on sacred ground; a family member on the other says the center would embody American religious freedom to counter the extremism that came to the fore that day (Hernandez, 2010, p. A22). This article describes a major element of this conict as opportunistic politicians who have latched onto the issue as a high-prole platform to attack their opponents (Hernandez, 2010, p. A22). For example, a gubernatorial candidate called for an investigation into the centers nances, an investigation that would have to be carried out by his opponent, the states attorney general, who, in turn, has rebuffed those requests (Hernandez, 2010, p. A22). The articles conclusion highlights the perspective of Muslims, noting that many were facing renewed hostility and worries that life in the United States may continue to be clouded with mistrust (Hernandez, 2010, p. A22). Yvonne Haddad, a professor at the Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at Georgetown University, states that building mosques makes a statement that we [Muslims] are here and we are here to stay, and some people would like to wish them away (p. A22). This article reveals the vitriolic, divisive, and politicized nature of the conict surrounding Park51. At the hearing of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, itself a site of conict, a larger conict plays out: how space surrounding Ground Zero should be allocated and used. This, like the dispute about the bus ad, is fundamentally about the inclusion or exclusion of Muslims within the United States. Theme 3: American Identity and Ideals The third theme, American Identity and Ideals, was present in 38 of the 65 articles in mentions of: full citizenship, civil rights, religious freedom, constitutional rights, international view of USA, anti-discrimination laws, how USA laws and rights apply in this conict, and responsibilities and moral norms that are or should be shared by Americans. N.Y. Political Leaders Rift Grows on Islam Center, published in The New York Times on August 25, 2010 reports on two prominent elected ofcials who each articulate a different understanding of American values to oppose or support Park51 (Barbaro, 2010a). The article opens with a description of Sheldon Silver, New York State Assembly Speaker, whose district includes Ground Zero, speaking at City Hall and encouraging the sponsors of Park51 to nd a different location. His remarks were delivered on the same day that New York City Mayor Bloomberg spoke in support of Park51 at a traditional Ramadan dinner at Gracie Mansion. Mayor Bloomberg linked the controversy over Park51 to two aspects of what it means to be an American: rights and ideals. This is a test of our American values, he said, and moving the center would slight American Muslims and damage the countrys standing (Barbaro, 2010a, p. A17). Speaker Silver also invoked what it means to be American in stating that he believes very rmly that our Constitution guarantees us the right to freedom of religion and that includes the, obviously, the right to build

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

houses of worship (p. A17). But then he urged sponsors of Park51 not to exercise that right. For Speaker Silver, the hallowedness of the area surrounding Ground Zero legitimates an exception to the normal application of American ideals, while Mayor Bloomberg took the position that these ideals must apply without exception. Describing the Mayors traditional Ramadan dinner at Gracie Mansion, the article reports that the Mayor read an excerpt of words written by Feisal Abdul Rauf, the Imam associated with Park51, in which Rauf describes his identication with Jews and Christians. This scenea Jewish mayor at a Muslim celebration reading an Islamic religious leaders words about cross-faith identication that were written for the funeral of a Jewish journalistimplies that what it means to be American is to support the ideal of religious diversity. The article reports that the mayor then seemed emotional and his voice began to crack (Barbaro, 2010a, p. A17) as he recited a Hebrew prayer. Sharif El-Gamal, Park51s developer, said Bloomberg touches my heart every time I hear him talk about our rights as Americans and his brave and unwavering statements (Barbaro, 2010a, p. A17). This article describes American values and identity as it connects with religious diversity and guarantees of religious freedom. Although both Speaker Silver and Mayor Bloomberg appear to agree that religious freedom is a core American value, this agreement is revealed as supercial when Speaker Silver argues that Park51s Muslim planners should not exercise their constitutional right to build the Islamic community center near Ground Zero. In this article, the Park51 conict is enacted by two major political gures at two key sites of New York City government, City Hall and Gracie Mansion, to debate questions of justice: who can exercise religious freedom, who should not, who really belongs here, and in what locales. Theme 4: Proximity and Place The theme, Proximity and Place, was present in 18 of the 65 articles, emerging in mentions of: proximity, hallowed ground, sacred space, distance, public space, location, and delement. This theme is attentive to physical distance, symbolic spatial issues (e.g., where the boundaries of Ground Zero lie), and differentiating sacred from secular space. The theme is evoked by questions about how far from Ground Zero hallowed ground extends and whether, realistically, a mosque can dele a neighborhood block that already includes an off-track betting establishment and a strip club. Debate Heats Up About Mosque Near Ground Zero, published in the New York Times on July 31, 2010 reports on conicts over the meaning of space on the periphery of Ground Zero. The article includes the perspectives of local and national politicians, faith leaders, and family members of victims of 9/11 (Barbaro, 2010b). Two Republicans, Rick Lazio and Carl Paladino, who each hope to be the partys candidate for governor in New York, spar over Park51. The Park51 controversy also becomes a central issue in political campaigns outside New York City and State. Readers are introduced to Ilario Pantano, a lesser known politician but the central subject of the article and pictured in a full color photograph that accompanies it. Mr. Pantano, a Republican candidate for U.S. Congress in North Carolina, has

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res Table 2 Geographic analysis: position on Park51 and location New York City (NYC) Number of speakers in support of Park51 Number of speakers in opposition to Park51 24 3 Outside NYC but within New York State (NYS) 5 11 Outside NYS 11 19 Total, N 40 33

campaigned on the issue [of the Park51 conict], and says it is stirring voters in his rural district, some 600 miles away from Ground Zero (p. A1). The article also includes views of leaders of faith-based organizations for and against the center, and quotes from politicians currently running for ofce. Barbaro offers the local perspective, noting that for New Yorkers, and particularly for Manhattanites, Ground Zero has slowly blended back into the fabric of the cityit is a construction zone, passed during the daily commute or glimpsed through ofce windows. To some outside of the city, though, it stands as a hallowed battleeld that must be shielded and memorialized (Barbaro, 2010b, p. A1). He suggests that there may be differences in how residents of Manhattan and others across the country conceptualize the physical space and symbolic meaning surrounding Ground Zero. Residential Locale and Support for Park51 To examine Barbaros (2010b) proposition that support for and opposition to Park51 may vary by geographic distance from the site, we identied the residential locale (in New York City, outside New York City but within New York State, or outside New York State) for each speaker quoted in the 65 New York Times articles who had a clear pro or con opinion regarding Park51 (N = 73). Speakers without a clear position on the centers construction or without a geographic locale specied were excluded from our sample. We then conducted Chi square analyses expecting to nd differences among these different groups, in particular that speakers from outside of New York City would be less likely to support Park51 than those from New York City, and that those from outside New York State would be even less likely to support Park51 than those within New York State (Table 2). Our rst Chi square test indicated that perceptions about Park51 differ signicantly based on whether the person resides in New York City, outside New York City but within New York State, or outside of New York State, v2 (2, N = 73) = 20.23, p \ .001. To further examine these differences, the Chi square was partitioned into two components that allow us to see where the differences between these groups lie (Rindskopf, 2005). Test 1 indicates that there is no difference in perceptions of Park51 between people living outside New York City but residing in New York State and people living outside New York State, v2

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

(1, N = 73) = 0.14, p = .713. Test 2 indicates a signicant difference in perceptions of Park51 between residents of New York City and residents of any locale outside New York City, v2 (1, N = 73) = 20.10, p \ .001, showing that those residing within New York City are more likely to support Park51 than those residing outside of it.

Discussion: Understanding the Park51 Conict Throughout the duration of the Park51 conict, the term, hallowed ground, was repeatedly invoked to refer not just to Ground Zero but also to some of the space that surrounds it. Borrowing from the Oxford English Dictionary (Sacred, 2013), we dene hallowed ground as referring to a place set apart for or dedicated to some purpose, entitled to veneration or made holy by association with an object of consecration. In Svendsen and Campbells (2010) study of community-based memorials to 9/11, they nd that in general, Americans are comfortable with representations of the sacred extending beyond spaces designated to contain them (e.g. churches, synagogues, mosques, cemeteries) (p. 320). This leakage of memory, affect, and reverence, what we see as sacred spillover, is crucial to understanding the nature of the Park51 controversy. As in other environmentally fraught sites, such as those contaminated with hazardous substances, the boundaries of an emotionally fraught site such as Ground Zero are not immediately clear. Just as radioactive material or other pollutants may spread far beyond an initial site of environmental trauma, the question of how far is far enough away from a site of emotional trauma may be difcult to measure. How far from the physical border of Ground Zero sacredness extends was a prominent and contentious issue throughout the conict. Mayor Bloomberg, who argued against moving the centers site because it would not quell controversy, satirically asked How big should the no-mosque zone around the World Trade Center be? (Barbaro, 2010a, p. A17). What makes some grounds hallowed and where those grounds end is discussed in a Letter to the Editor of the New York Times which noted that sites of memory likethe Twin Towers include not only the immediate buildings, but large swaths around them that I know from personal experience arent measured in meters or yards, but in emotional sparks (Aizenberg, 2010, p. A30). This notion of calibrating measurements using emotional sparks resonates with four psychological concepts: place attachment, social distance, the Gestalt construct of propinquity, and justice. Place Attachment Our data reveal that a major feature of the conict surrounding Park51 are different meanings associated with Ground Zero, recalling the construct, place attachment. Studied by Low and Altman (1992) to examine humanplace bonding, place attachment is an integrative construct connecting the affective, cognitive, and behavioral attachments of different actors who are embedded in social relationships and to places over time. Low and Altman recognize that attachments may not be to

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

landscapes solely as physical entities, but may be primarily associated with the meanings of and experiences in a place which often involve relationships with other people (p. 7). Meanings associated with a place can also shift over time in response to relocation, environmental disasters, and other pivotal events (Low, 1992). Consistent with this inuential line of environmental psychology research (cf., Kyle & Chick, 2007), our study nds that a site on the periphery of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan and its envisioned use brought into public debate strong senses of place attachment, both retrospectively and prospectively, in support and opposition, with strong affective, cognitive, and behavioral components that entwined with passionate beliefs about values, fairness, and justice. Distance Distance played an important factor in all of the articles. We see three approaches to understanding the meaning of distance as useful: social distance, propinquity, and geographic distance. Social Distance In 1926, Bogardus operationalized the construct, social distance, to measure fellow-feeling and understanding (Bogardus 1926, p. 41). The scale he devised included a listing of 57 statements that range from more to less fellow-feeling and understanding, anchored by would marry and would exclude from my country. In his research, participants were asked to state which, if any, of the social relationships on a list he provided they would approve for members of specic ethnic groups. The scale has been translated into several languages and is widely used in many countries to measure attitudes toward ethnic, religious, and other minority groups (Wark & Galliher, 2007) (Table 3). The interval categories Bogardus developed to measure social distance are analogous to attitudes we found in our analysis of the 65 New York Times articles on the Park51 conict. We propose an adaptation of Bogarduss ve-point scale, which we call the socialenvironment distance scale (SEDS), to measure peoples willingness to allow a site within spaces they care about. Like Bogarduss scale, SEDSs statements range from inclusion in kinship ceremonies to complete societal exclusion. As Bogardus conceptualized foreclosing the possibility of admitting a

Table 3 Social and environmental distance scales Bogardus social distance scale (Wark & Galliher, 2007) Social environment distance scale I would marry this person I would get married in a mosque I would have this person as a close friend I would visit a mosque regularly I would allow this person to live on my street I would allow a mosque on my street I would allow this person to be a member of my occupation I would allow a mosque in my neighborhood I would allow this person to be a citizen of my country I would allow mosques in my country

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

member of a particular ethnic or religious group into part of ones life as indicative of greater social distance, we conceptualize a similar refusal to visit a Mosque or other site in ones community to indicate greater socialenvironmental distance. Similarly, if one is open to utilizing a site for deeply meaningful kinship ceremonies, less socialenvironmental distance is indicated, paralleling Bogarduss anchor of least social distance in which one would marry a member of that group. Consistent with Bogardus (1926) observation that despite the physical proximity of the city, social distance prevails (p. 40); social distance and spatial distance are not the same, nor is physical distance the same as psychological distance. What is considered close or far varies across socio-environmental contexts. Peoples psychological representations of space are different from space as measured in inches and miles (Tversky, 2003). Propinquity Regarding the siting of Park51 two blocks from Ground Zero, Abdel Moety Bayoumi, a member of the Islamic Research Institute at Al Azhar, stated that It will create a permanent link between Islam and 9/11 (Cambanis, 2010, p. A12). His statement, intended to caution against such a linkage, evokes the Gestalt Principle of Propinquity (Bannerjee, 1994) in which two things that are seen as adjacent to each other are perceived as related. The Why there? bus advertisement attempts to visually and discursively forge a link between 9/11 and Park51 by placing the smoldering World Trade Center Towers and a building supposed to represent Park51 next to each other, rendered in an unrealistically similar size and in a similar shade of gray, captioned with the parallel capitalized phrases SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 WTC JIHAD ATTACK, and SEPTEMBER 11, 2011 WTC MEGA MOSQUE. The supposed resemblance of the buildings and the textual analogy is underscored by a large doublesided arrow connecting the two. These strategies attempt to collocate Park51 and 9/11 not only in the advertisement but also in the minds of viewers. An article examining the parallels and discontinuities between the Park51 controversy and European mosque conicts includes a quote from one of the most senior Islamic clerics in France saying that there are symbolic places that awaken memories whether you mean to or not. And it isnt good to awaken memories (Cambanis, 2010, p. A12). Differing perceptions of whether the location of Park51 would awaken difcult memories appears to depend on where people set the boundaries of Ground Zero and whether the meanings they attached to Ground Zero preclude the presence of Muslims. Geographic Distance The two sites, Ground Zero and Park51, which are not necessarily linked become so through advertisements, political propaganda, and public debate in the news. This associative link may be more effective with some people than others, as indicated by the Chi square analyses. New Yorkers seemed to have viewed the two sites as discrete, while those outside the city saw them as connected. A more outsider (etic) perspective of the conict may only view Ground Zero and the future site of Park51

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

in relation to each other, ignoring the blocks between them and the wedding cake producer, oncology center, espresso bar, carpet cleaning service, and other sites that lie between. A closer (emic) view of the sites may see these two sites in relation to the fabric of the city in which they are imbedded rather than as symbols with antithetical meanings. The wide residential geographic range of those quoted in The New York Times demonstrates that the phenomena, place attachment, is not limited to places individuals have lived in, currently live in, or places that are nearby, but that place attachment extends to sites imbued with collective meaning and viewed as hallowed ground. Our Chi square analyses of support for and opposition to Park51 and its relation to geographic distance from the site suggest that those living within New York City have a different conception of Ground Zero and its surrounding area than those living outside New York City. The two-block distance between Park51 and Ground Zero may seem insensitively close to people outside New York City, but two blocks may be a greater distance to those who live in this dense urban environment where each street has its own commercial and residential environment and where neighborhoods may have tightly drawn boundaries (cf., Haberman, 2010, p. A16). The concentration of support for Park51 from those living close to its physical location and opposition for those farther away suggests that differently situated individuals, ideologically and geographically, understand the meaning and nature of a site from distinct perspectives. Thus, conceptions of justice can vary depending on positionality, particularly from proximal and distal vantage points. Justice The question How near is near? although ostensibly a geographic question is laden with important distributive, procedural, and inclusionary justice issues. We discuss each of these justice contingencies in turn. Distributive Justice Throughout the articles, distributive justice questions are evident in statements about valued social resources and questions of rights, deserving, and entitlement attached to those goods. In the Park51 controversy, salient resources are land, access to a public platform, and social legitimacy. Distributive justice issues are apparent in debates and hearings that can allocate the permission to build on the plot of land in Lower Manhattan, a valuable and scarce resource because of the high urban density in Lower Manhattan. Distributive justice is also apparent in the value attached to Park51, whether or not it is deemed a sacred site. Distributive justice also plays out in having the power to disseminate information and be heard. For example, the exchange between Speaker Silver and Mayor Bloomberg about what it means to be an American concerns distributive justice in the ability of some people and their positions to garner attention. Speaker Silver can speak at City Hall and Mayor Bloomberg can host a Ramadan dinner at Gracie Mansion, and both these events were deemed newsworthy and reported on by an international newspaper, a valued platform for disseminating ideas and positions. From a

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

distributive justice perspective, these venues and this coverage are resources that are not allocated equally or available to all. The anti-Park51 advertisement that eventually ran on the sides of New York City buses makes a claim about justice that literally moves through the urban environment and reaches millions of people. From a distributive justice standpoint, this ad is a resource because it is a platform for promulgating ideological beliefs. Procedural Justice Within the Park51 controversy procedural justice is evident in the processes that ultimately allocated advertising space on buses and that rejected claims to landmark status. These were formal procedures, but rhetoric at public events or in the media also debate procedural justice issues that can shift public opinion about what decisions are made and who will participate in making them. The Why there? bus advertisement illustrates how distributive and procedural justice are interwoven and feed into each other, amplifying privilege and resources in the process. Those groups who already held access to certain privileges were able in the conict to magnify that privilege through formal and informal avenues. Procedural justice involved formal challenges using or opposing laws, rules, and regulations, as well as informal activities to inuence popular opinion such as paying for an advertisement, ling a lawsuit, and invoking claims to free speech. How one goes about making claims about justice segues into what resources can be worked to ones advantage. And, relatedly, what resources one has inuences how one can make claims. Thus, we see distributive and procedural justice as closely linked in our data. Inclusionary Justice Inclusionary justice pervaded the debate in questions of who belongs and who does not. The bus advertisement (Grynbaum, 2010) as well as other examples in our data, such as the description of Park51 as sacrilege on sacred ground (Hernandez, 2010, p. A22) promulgate an exclusionary logic positioning Muslims as an outgroup that should be excluded because they threaten America. The bus advertisements implicit claims about Muslims connects them with 9/11 and connects Park51 with bombing and terrorist-initiated destruction to quash Park51 with the more general aim of excluding Muslims from the USA. The four articles we chose to analyze in depth illustrate the larger tendency for Muslim voices to be less prominent in our sample of 65 articles. Ordinarily, a sites developer plays a prominent role, such as Larry Silverstein, the developer of the World Trade Center site. But the right of Park51s developer, Sharif El-Gamal, to take an active part in decision-making is rarely mentioned in this set of articles on the conict. This occurs while other people, such as Ilario Pantano, who lives and works 600 miles away in North Carolina, claims this site as American and this conict as his own. These articles indicate that deeming a site hallowed can justify excluding some groups from consideration or participation in the public debate about the use of this space even when that group is centrally connected to that site. The ability to dene the dimensions of sacredness and what constitutes sacrilege

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

can be powerful rhetorical tools to justify the exclusion of particular groups. In this conict, the social construction of sacredness interacted with the virulently Islamophobic discourses present in the United States after 9/11 to depict the Park51 proposal as controversial and, consequently, debatable. As previously noted, the three key organizers of the center were scrutinized in the press, and some articles (e.g., Hernandez, 2010) featured the perspective of Muslims, particularly the hostility and mistrust they faced. This seems contradictory: in some ways, Muslim voices and perspectives were relegated to the margins while Muslims were also hyper-scrutinized. As Sirin and Fine (2008) observe, after 9/11 Muslims in the USA were placed under suspicion, socially and psychologically, within the nation they considered home (p. 7). Citing Bhabha (2005), they describe American Muslims as over-looked- in the double sense of social surveillance and psychic disavowal (p. 13). Similarly, our analysis suggests that an interaction of distributive, procedural, and inclusionary injustice consistently positioned Muslims as peripheral to and muted in the public debate even while they were scrutinized. Those who are not considered to be genuinely American are rarely afforded the legitimacy to discuss topics debated in the public sphere, even topics that deeply effect their individual and collective lives; in this case, inclusion in or exclusion from American identity. Park51 Today As we write this paper, Park51 has not yet demolished the buildings at 4547 and 4951 Park Place to begin construction on the planned 13 story community center. However, Park51 did open to the public on September 21, 2011 with a surprisingly quiet and controversy-free public event, NYChildren, an exhibition of 160 portraits of immigrant children now living in New York City (see http://park51.org/ 2011/10/nychildren_exhibit/). The 4547 Park Place building now contains 4,000 square feet of renovated space that is used for weekly prayer services, interfaith workshops, lectures, lms, and exhibitions. Its website states: Park51 will be a vibrant and inclusive community center, reecting the diverse spectrum of cultures and traditions, and serving New York City with programs in education, arts, culture and recreation. Inspired by Islamic values and Muslim heritage, Park51 will weave the Muslim-American identity into the multicultural fabric of the United States. Park51 aims to foster cooperation and understanding between people of all faiths and backgrounds through relevant programs and initiatives (Park51, 2013).

Conclusion Conict and Justice on Hallowed Ground As our thematic analysis indicated, this high-prole conict over space engaged deep divisions between different conceptions of the meaning of Islam, American identity, and the appropriate use of space surrounding Ground Zero. It opened a

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res

window into distributive justice and the resources at stake in the conict, which included claims to American identity, the site itself, legal rights and documents, and public platforms to speak. This conict also illuminated procedural justice issues including formal decision-making processes such as approval by the local Community Board and the Landmarks Preservation Commission, as well as informal decision-making processes such as the court of public opinion. We saw inclusionary justice at the heart of the conict in fundamental questions about who can speak, who belongs, and who some people would like to wish away (Hernandez, 2010, p. A22). Our ndings regarding residential location and support for Park51 suggest differing conceptions of socialenvironmental space by differently situated individuals, and would benet from further study of how sites of conict are viewed from proximal and distal vantage points. At the time of writing, resistance to the construction of mosques is continuing in both the United States (Obeidallah, 2013) and Europe (ENAR, 2013), having become a standard trope of Islamophobic discourse. Based on this study of the Park51 controversy, ensuing debates over the appropriate use of those spaces will involve questions of distributive, procedural, and inclusionary justice much like those reported here. We see the psychology of justice has having important applications in those conictual contexts. Insights gained in this study at the intersection of the environment and justice may generalize to other disputes over places called hallowed ground that embody national or cultural history, memory, and trauma including the usage or appropriation of sacred indigenous sites; the city of Jerusalem and other religious sites. Such conicts are likely to evoke questions of who has a legitimate claim on determining the future of the site, how far sacredness extends, and they will surely surface the question, Why there?

Acknowledgments We thank Naomi Podber for her assistance, and we appreciate helpful comments on an earlier draft by Dominique Grisard, Markus Brunner, anonymous reviewers, and the editors.

References

Ahmad, M. (2002). Homeland insecurities: Racial violence the day after September 11. Social Text, 20(3), 101115. Aizenberg, E. (2010, September 21). Muslims and the apology question. [Letter to the editor]. The New York Times, p. A30. Amer, M. M., & Bagasra, A. (2013). Psychological research with Muslim Americans in the age of Islamophobia. American Psychologist, 68(3), 134144. Bannerjee, J. C. (1994). Gestalt theory of perception. In J. C. Bannerjee (Ed.), Encyclopeadic dictionary of psychological terms. New Delhi: MD Publications. Barbaro, M. (2010a, August 25). N.Y. political leaders rift grows on Islam center. New York Times, p. A17. Barbaro, M. (2010b, July 31). Debate heats up about mosque near Ground Zero. New York Times, p. A1. Barbaro, M., & Hernandez, J. C. (2010, August 4). Mosque plan clears hurdle in New York. New York Times, p. A1. Barnard, A. (2011, August 2). Developers of Islamic center try a new strategy. New York Times, p. A21. Barranco, J., & Wisler, D. (1999). Validity and systematicity of newspaper data in event analysis. European Sociology Review, 15, 301322. Bhabha, H. K. (2005). Race, time, and the revision of modernity. In C. McCarthy, W. Crichlow, G. Dimitriadis, & N. Dolby (Eds.), Race, identity, and representation in education. New York: Routledge.

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res Bilici, M. (2005). American jihad: Representations of Islam in the United States after 9/11. American Journal of Social Sciences, 22, 5069. Bleich, E. (2011). What is Islamophobia and how much is there? Theorizing and measuring an emerging comparative concept. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(12), 15811600. Blumenthal, R. & Mowjood, S. (2009, December 9). Muslim prayers and renewal near Ground Zero. New York Times, p. A1. Bogardus, E. S. (1926). Social distance in the city. Proceedings of the American Sociological Society, 20, 4046. Cambanis, T. (2010, August 26). Looking at Islamic center debate, world sees U.S. New York Times, p. A12. Cesari, J. (2005). Mosque conicts in European cities: Introduction. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31(6), 10151024. Clayton, S., & Opotow, S. (2003). Justice and identity: Changing perspectives on what is fair. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7(4), 298310. Coser, L. (1956). The functions of social conict. New York: Free Press. Deutsch, M. (1969). Conicts: Productive and destructive. Journal of Social Issues, 25(1), 741. Deutsch, M. (1973). The resolution of conict: Constructive and destructive processes. New Haven, CT: Yale. Deutsch, M. (1985). Distributive justice: A social psychological perspective. New Haven, CT: Yale. Dunlap, D. W. (2010, August 25). When an Arab enclave thrived downtown. New York Times, p. A16. Earl, J., Martin, A., McCarthy, J. D., & Soule, S. (2004). The use of newspaper data in the study of collective action. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 6580. ENAR. (2013). Racism in Europe ENAR shadow report 20112012. Brussels: European Network Against Racism. Foa, U. G., & Foa, E. B. (1974). Societal structures of the mind. Springeld, IL: Charles C. Thomas. Geminder, E. (2010, July 20). 45 Park Places place. New York Observer. Retrieved July 6, 2013 from http://observer.com/2010/07/45-park-places-place/. Geschke, D., Sassenberg, K., Ruhrmann, G., & Sommer, D. (2010). Effects of linguistic abstractness in the mass media: How newspaper articles shape readers attitudes toward migrants. Journal of Media Psychology, 22(3), 99104. Grynbaum, M. M. (2010, August 12). Dispute over ad opposing Islamic center highlights limits of the MTAs powers. New York Times, p. A22. Haberman, C. (2010, August 24). Ground zero: Its boundaries are elastic. New York Times, p. A16. Harwood, S. A. (2005). Struggling to embrace difference in land-use decision making in multicultural communities. Planning, Practice, and Research, 20(4), 355371. Hernandez, J. C. (2010, July 14). Planned sign of tolerance bringing division instead. New York Times, p. A22. Khan, M., & Ecklund, K. (2012). Attitudes toward Muslim Americans post 9/11. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 7(1), 116. Kyle, G., & Chick, G. (2007). The social construction of a sense of place. Leisure Sciences, 29(3), 209225. Leventhal, G. S. (1979). Effects of external conict on resource allocation and fairness within groups and organizations. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterrey, CA: Brooks/Cole. Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum. Low, S. (1992). Symbolic ties that bind: Place attachment in the plaza. In I. Altman & S. Low (Eds.), Place attachment. New York: Plenum Press. Low, S., & Altman, I. (1992). Place attachment: A conceptual inquiry. In I. Altman & S. Low (Eds.), Place attachment. New York: Plenum Press. Martin, S. E., & Hansen, K. A. (1998). Newspapers of record in a digital age: From hot type to hot link. London: Greenwood. Nafstad, H. E., & Blakar, R. M. (2012). Ideology and social psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(4), 282294. Obeidallah, D. (2013, September 28). Fox host wants to take away my rights. CNN. Retrieved September 29, 2013 from http://www.cnn.com/2013/09/28/opinion/obeidallah-beckel-muslims/index.html. Opotow, S. (1990). Moral exclusion and injustice: An introduction. Journal of Social Issues, 46(1), 120.

123

Author's personal copy

Soc Just Res Opotow, S. (1995). Drawing the line: Social categorization, moral exclusion, and the scope of justice. In B. B. Bunker & J. Z. Rubin (Eds.), Conict, cooperation, and justice (pp. 347369). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Opotow, S. (1997). Whats fair? Justice issues in the afrmative action debate. American Behavioral Scientist, 41(2), 232245. Opotow, S., & Clayton, S. (1994). Green justice: Conceptions of fairness and the natural world. Journal of Social Issues, 50(3), 111. Opotow, S., & Gieseking, J. (2011). Foreground and background: Environment as site and social issue. Journal of Social Issues, 67(1), 179196. Opotow, S., & Weiss, L. (2000). Denial and the process of moral exclusion in environmental conict. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 475490. Ortiz, D. G., Myers, D., Walls, N. G., & Diaz, M. D. (2005). Where do we stand with newspaper data? Mobilization, 10(3), 397419. Park51 (2013, July 6). Mission. Retrieved July 6, 2013 from http://www.park51.org/mission. Rindskopf, D. (2005). Decomposition of Chi Square. In B. S. Everitt & D. Howell (Eds.), The encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Sacred. (2013). Oxford English Dictionary online. Retrieved July 6, 2013 from http://www.oed.com. ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/view/Entry/169556?redirectedFrom=sacred&. Salles, C. (2010). Media coverage of the internet: An acculturation strategy for press of record? Innovation in Journalism, 7(1), 314. Sheridan, L. P. (2006). Islamophobia pre- and post-September 11th, 2001. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(3), 317336. Sirin, S. R., & Fine, M. (2008). Muslim American Youth: Understanding hyphenated identities through multiple methods. New York: NYU Press. Stewart, C. O., Pitts, M. J., & Osborne, H. (2011). Mediated intergroup conict: The discursive construction of illegal immigrants in a regional U.S. Newspaper. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 30(1), 827. Sunier, T. (2005). Constructing Islam: Places of worship and politics of space in the Netherlands. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 13(3), 317334. Svendsen, E. S., & Campbell, L. K. (2010). Living memorials: Understanding the social meanings of community-based memorials to September 11, 2001. Environment and Behavior, 42(3), 318334. Thibaut, J., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Triandafyllidou, A., & Gropas, R. (2009). Constructing difference: The mosque debates in Greece. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35(6), 957975. Tversky, B. (2003). Structures of mental spaces: How people think about space. Environment and Behavior, 35, 6680. Vitello, P. (2010, August 24). Amid furor on Islamic center, please for Orthodox Church nearby. New York Times, p. A16. Wark, C., & Galliher, J. F. (2007). Emory Bogardus and the origins of the social distance scale. American Sociologist, 38, 383395. Wester-Herber, M. (2004). Underlying concerns in land-use conicts- the role of place-identity in risk perception. Environmental Science & Policy, 7(2), 109116.

123

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Sacred Space Muslim and Arab Belonging at Ground ZeroDocumento19 pagineSacred Space Muslim and Arab Belonging at Ground ZeroPatrick SweeneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Lewin Award Introduction 1958Documento4 pagineLewin Award Introduction 1958Patrick SweeneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Surveillance and Privacy Technologies Impact On IdentityDocumento19 pagineSurveillance and Privacy Technologies Impact On IdentityPatrick SweeneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Artforum Mcdonough Adam-Pendleton November 20113Documento8 pagineArtforum Mcdonough Adam-Pendleton November 20113Patrick SweeneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Berlin in Your Pocket June 2014Documento35 pagineBerlin in Your Pocket June 2014Patrick SweeneyNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

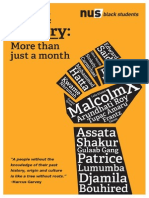

- Black History: More Than Just A MonthDocumento23 pagineBlack History: More Than Just A Monthnusbsc14100% (1)

- Islam Phobia John EspostisoDocumento99 pagineIslam Phobia John EspostisoAinaa NadiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Islam and HumanityDocumento13 pagineIslam and HumanityMuhammad Tausif HashimNessuna valutazione finora

- ICV Response to Double Standards in Peace Conference CoverageDocumento2 pagineICV Response to Double Standards in Peace Conference CoverageAbulNessuna valutazione finora

- 19 P Aurat MarchDocumento15 pagine19 P Aurat MarchJOURNAL OF ISLAMIC THOUGHT AND CIVILIZATIONNessuna valutazione finora

- Modern Myths of Muslim Antsemitism EnglishDocumento10 pagineModern Myths of Muslim Antsemitism EnglishDahlia ScheindlinNessuna valutazione finora

- López Prater - Press ReleaseDocumento28 pagineLópez Prater - Press ReleaseWCCO - CBS MinnesotaNessuna valutazione finora

- Majed (1) Master Thesis Islam and Muslim Identities in Four Contemporary British NovelsDocumento251 pagineMajed (1) Master Thesis Islam and Muslim Identities in Four Contemporary British NovelsHalil ÖzdemirNessuna valutazione finora

- Issue OneDocumento20 pagineIssue OneDimitris DavrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Excluding Muslim Women: From Hijab To Niqab, From School To Public SpaceDocumento8 pagineExcluding Muslim Women: From Hijab To Niqab, From School To Public SpaceSolSomozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Terrorism in Islam and The Rise of Islamic Phobia: How It May Impact Human RelationsDocumento23 pagineTerrorism in Islam and The Rise of Islamic Phobia: How It May Impact Human RelationsAri Wijanarko Adipratomo, A.A.Nessuna valutazione finora

- IGCSE GP Individual ReportDocumento5 pagineIGCSE GP Individual ReportPoorvash MNessuna valutazione finora

- (Palgrave Politics of Identity and Citizenship Series) Rosi Braidotti, Bolette Blaagaard, Tobijn de Graauw, Eva Midden (Eds.)-Transformations of Religion and the Public Sphere_ Postsecular Publics-PalDocumento292 pagine(Palgrave Politics of Identity and Citizenship Series) Rosi Braidotti, Bolette Blaagaard, Tobijn de Graauw, Eva Midden (Eds.)-Transformations of Religion and the Public Sphere_ Postsecular Publics-PalfadmulNessuna valutazione finora

- The Official Anti-Milo ToolkitDocumento31 pagineThe Official Anti-Milo ToolkitLucas Nolan30% (10)

- Andreas Breivik's Mental BackgroundDocumento4 pagineAndreas Breivik's Mental BackgroundAnte VrankovićNessuna valutazione finora

- FEMYSO - Annual Report 2014Documento32 pagineFEMYSO - Annual Report 2014FEMYSONessuna valutazione finora

- Organizational behavior explored in My Name is KhanDocumento19 pagineOrganizational behavior explored in My Name is KhanFaiz AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Shannahan - Qome Queer Questions From A Muslim Faith PerspectiveDocumento14 pagineShannahan - Qome Queer Questions From A Muslim Faith PerspectivemargitajemrtvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay 3Documento9 pagineEssay 3api-210601344Nessuna valutazione finora

- Intro Muslim Studies LaurierDocumento9 pagineIntro Muslim Studies Lauriersheryl.13Nessuna valutazione finora

- Radiant Reality April 2012Documento40 pagineRadiant Reality April 2012takwaniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Islamophobia - Issues, Challenges & ActionsDocumento100 pagineIslamophobia - Issues, Challenges & Actionsnujikabane100% (6)

- Puar Postscript Terrorist - Assemblages - Homonationalism - in - Queer - Tim... - (PG - 260 - 274)Documento15 paginePuar Postscript Terrorist - Assemblages - Homonationalism - in - Queer - Tim... - (PG - 260 - 274)Cătălina PlinschiNessuna valutazione finora

- Sinhala Buddhist Nationalism and Islamophobia in Contemporary Sri LankaDocumento152 pagineSinhala Buddhist Nationalism and Islamophobia in Contemporary Sri Lankakomathi nadarasaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Decline of The Traditional Orientalism in Don Delillo's Falling ManDocumento11 pagineThe Decline of The Traditional Orientalism in Don Delillo's Falling ManIJELS Research JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- India Country Report 2023Documento1 paginaIndia Country Report 2023System DzNessuna valutazione finora

- Intolerance and Cultures of Reception in Imtiaz Dharker Ist DraftDocumento13 pagineIntolerance and Cultures of Reception in Imtiaz Dharker Ist Draftveera malleswariNessuna valutazione finora

- Jumah Khutbah - BosniaDocumento5 pagineJumah Khutbah - BosniaMPACUKNessuna valutazione finora

- NZ Delegation Paper on Religious DiscriminationDocumento2 pagineNZ Delegation Paper on Religious DiscriminationAtabey IbrahimliNessuna valutazione finora

- Albanian dervishes versus Bosnian ulema: popular sufism in KosovoDocumento23 pagineAlbanian dervishes versus Bosnian ulema: popular sufism in KosovotarikNessuna valutazione finora