Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

In Re R. Krishnan Vs Unknown On 6 December, 1957

Caricato da

Knowledge GuruTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

In Re R. Krishnan Vs Unknown On 6 December, 1957

Caricato da

Knowledge GuruCopyright:

Formati disponibili

In Re: R.

Krishnan vs Unknown on 6 December, 1957

Madras High Court Madras High Court In Re: R. Krishnan vs Unknown on 6 December, 1957 Equivalent citations: (1958) 1 MLJ 189 Author: R Ayyangar ORDER Rajagopala Ayyangar, J. 1. The petitioner who is seeking enrolment as an Advocate of this Court has filed this petition praying for the order that he might be exempted from payment of the Stamp duty payable for the entry of his name as an Advocate of this Court. 2. The petitioner is a graduate in law of this University and was enrolled as an Advocate of the former Mysore High Court when Mysore was a " Part B " on. 20th January, 1955. He states that he was admitted to the roll of that Court on payment of Rs. 300 which was prescribed by the Mysore Stamp Act then in force. After Mysore became a " Part A " State as a result of the States Reorganisation Act the petitioner became an Advocate of the Mysore High Court under the proviso to Section 53(2) of the States Reorganisation Act. He claims that as he has been enrolled as an Advocate of a High Court--the Mysore High Courthe is exempt from the payment of any Stamp duty under Article 25 of Schedule I-A of the Stamp Act as amended in the Madras State. 3. Notice of this application was given to the Advocate-General and we have had the benefit of his submissions on the relevant statutory provisions. By our order, dated 4th November, 1957 the exemption prayed for has been granted but we announced that our reasons would be pronounced later. 4. The levy of Stamp duty payable on enrolment is by virtue of Article 25 of Schedule I-A of the amendments effected to the Indian Stamp Act by the Madras Act VI of 1922. This provision reads: 25. Entry as an Advocate, Vakil or Attorney on the roll of any High Court under the Indian Bar Coucils Act, 1926 or in exercise of powers conferred on such Court by Letters Patent or by the Legal Practitioners Act, 1884. (a) in the case of an .. Six Hundred and twenty- Advocate or Vakil five rupees. (b).... Exemption. Entry of an Advocate, Vakil or Attorney on the roll of any High Court, when he has previously been enrolled in a High Court. It would therefore be seen that the only question to be considered is whether the High Court of Mysore is " a High Court " within the meaning of the exemption. Similar questions have come up for decision earlier in this Court and we shall first refer to these decisions before dicussing the precise scope of the statutory provisions. 5. In the matter of Krishnaswami (1942) 1 M.L.J. 599 5 I.L.R. (1942) Mad. 663 (F.B.)., dealt with the question whether an Advocate who had been enrolled in the Rangoon High Court and who subsequently sought, enrolment in the Madras High Court came within the exemption. A Full Bench of this Court answered this in the affirmative. Leach, C.J., who delivered the judgment of the Court saying: That Article 30 of the Indian Stamp Act (It is obviously a mistake because the stamp duty in the Madras State in respect of the relevant entry is governed not by Article 30 in Schedule I to the Indian Stamp Act but by

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/657552/ 1

In Re: R. Krishnan vs Unknown on 6 December, 1957

Schedule I.A introduced by the Madras Act VI of 192a where this. Article is numbered as 25) exempts an Advocate who has already paid the required fee on enrolment in a High Court from payment of it when he is enrolled in another High Court. The term . 'High Court' of course must be deemed to be a High Court established in British India. The Rangoon High Court can no longer be regarded as an Indian High Court, but it had that status when the petitioner was enrolled, and as he paid the fee required by the Stamp Act on that occasion we consider that he comes within the exemption contained in the article. The next decision on this point is by a Bench of this Court in Abdul Khader, In re . The petitioner was an Advocate of the Travancore-Cochin High Court--a High Court in a Part B State. The learned Judges held that the petitioner was not entitled to the exemption. This was rested on two bases : (1) the benefit of the exemption could arise only in cases where the main entry itself would be applicable ; that is, the original enrolment referred to in the exemption must be of the same class as the class of enrolment which the petitioner seeks. The Travancore-Cochin High Court was a High Court in a Part B State and so was not of the same category or class as the Madras High Court--a High Court in a Part A State. (2) The: High Court referred to in the exemption is a High Court within the territory to which the Stamp Act applied, in this respect following the decision of the Full Bench in Krishnaswami's Case (1942) 1 M.L.J. 599 5 I.L.R. (1942) Mad.663(F.B.). The Indian Stamp Act did not extend to -Travancore-Cochin and hence an enrolment in the Travancore-Cochin High Court would not be an enrolment in "a High Court " within the exemption....A Bench of the Andhra Pradesh High Court followed the decision of the Bench of this Court in Adbul Khader, In re , vide, Mannava Venkata Rao, In re (1957) 1 An.W.R. 244 and held that Advocates of the Mysore High Court could be enrolled in the Andhra Pradesh High Court without payment of any stamp duty by reason,. of their case being covered by the exemption, the reasoning upon which this decision. was rested being that the Indian Stamp Act was in force in Mysore even while it was a Part B State that is before the States Reorganisation Act by reason of the Indian Stamp (Amendment) Act (XLIII of 1955) and that as the petitioner was on the roll of the Advocates of the Mysore High Court by reason of the proviso to Section 53(2) of the States Reorganisation Act, both the conditions posited by the -decision in Adbul Khader , In re, were satisfied. 6. There cannot be any doubt that the petitioner satisfied the first condition laid down in Adbul Khader, In re (1953) 2 M.L.J. 457, namely his name being entered on the roll of a High Court of the same category as the Madras High Court. Mysore is under Act XXXVII of 1956 (The States Reorganisation Act) a Part A State and the High Court of Mysore is therefore a High Court of the class or category as the Madras. High Court. The petitioner whose name was borne on the roll of the High Court. of Mysore when it was a Part B State is now automatically on the roll of the Mysore High Court as now constituted. The proviso to Section 53(2) of the Act enacts: Provided that, subject to any rule made or direction given by the High Court for a new State in exercise of the power conferred by this section, any person who, immediately before the appointed day, is an Advocate entitled to practice or an Attorney entitled to act in any such High Court...as may be specified in this behalf by the Chief Justice of the High Court for the new State, shall be recognised as an Advocate or Attorney entitled to practice or to act, as the case may be, in. the High Court for the new State. The question that remains for consideration therefore is whether the other condition laid down in Adbul Khadar's Case (1953) 2 M.L.J. 457, namely that the enrolment must be in the High Court to which the Stamp Act applies is satisfied by the petitioner. Incidentally we might mention that the question has also been raised as to whether it is necessary to satisfy this condition. 7. The learned judges of the Andhra Pradesh High Court have held that Mysore was a territory to which the Stamp Act was made applicable by reason of the Central Act (XLIII of 1955). It has however been pointed out that the extension of the Indian Stamp Act to the Part B States is not absolute but subject to the conditions laid down in the enactment. Though Section 2 of Act XLIII of 1955 enacted:

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/657552/

In Re: R. Krishnan vs Unknown on 6 December, 1957

In the Indian Stamp Act, 1899....Unless otherwise expressly provided, the States (which meant the Part A States) wherever they occur, the word 'India' shall be substituted. Section 3 of the Amending Act specifically enacted a proviso as regards the extent of the operation of the enactment: Section 1 (2) : It extends to the whole of India except the State of Jammu and Kashmir. Provided that it shall not apply to Part B States....except to the extent to which the provisions of this Act relate to rates of stamp duty in respect of the documents specified in Entry 91 of List I in the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution. It was pointed out that this qualification in the extension of the Stamp Act was not noticed by the learned Judges of the Andhra Pradesh High Court whose judgment appears to proceed on the basis that Article 30 of the Schedule I of the Indian Stamp Act which related to the stamp duty payable for the entry on the roll of .the Advocates was in operation in the Mysore State when the Advocate, who sought enrolment in the Andhra Pradesh High Court was enrolled in Mysore when the latter was a Part B State. There is no doubt that this aspect is not adverted to in the judgment of Subba Rao, C.J. But in our opinion this does not affect the correctness of the decision. 8. Admittedly the stamp duty paid by the petitioner when he was enrolled in Mysore, was under the Mysore Stamp Act and not under Article 30 of Schedule I of the Indian Stamp Act, 1899. But in our opinion the argument which seeks to deny to a payment under the Mysore Stamp Act the efficacy of a payment under Article 30, Schedule I of the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, ignores the constitutional basis upon which Legislation in relation to stamp duties rests in India. At the time when the Indian Stamp Act, 1899 (a central enactment) was enacted the duties levied under each of the several articles in its Schedule became part of central revenues, no part of it being specifically allocated to the provinces. A change was however introduced into this system by the Montford Reforms of 1919. 9. Section 45-A of the Government of India Act, 1919, enacted: 45-A (1) Provision may be made by rules under this Act: ... (b) for the devolution of authority in respect of provincial subjects to local Governments and for the allocation of revenues or other moneys to those Governments. Devolution Rules were framed under this provision and Rule 14(1) read: 14 (1): The following sources of revenue shall in the case of Governors provinces be allocated to the local Government as sources of provincial revenue namely : ... (b) receipts accruing in respect of provincial subjects. ... (f) the proceeds of any taxes which may be lawfully imposed for provincial purposes.

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/657552/

In Re: R. Krishnan vs Unknown on 6 December, 1957

Schedule I to these rules classified subjects of Legislative power into two heads, Central and ProvincialParts I and II respectively. Item 20 of Part II List of Provincial subjects ran in these terms: 20. Non-judicial stamps, subject to legislation by the Indian legislature.... Section 80-A(3) laid down the formal requirements which the Provincial Legislatures should comply before enacting these laws': 80-A(3) : The local Legislature of any province may not, without the previous sanction of the Governor-General, make or take into consideration any law (a) imposing or authorising the imposition of any tax unless the tax is a tax scheduled as exempted from this provision by rules made under this Act : or. In pursuance thereof the Scheduled Taxes Rules were framed which specified the taxes which might be imposed by the provinces either for their purposes or for the purposes of local authorities within them without the previous sanction of the Governor-General. In regard to stamp duties Item 8 of the Schedule I to these rules enabled provincial legislation without previous sanction only in regard to 8. A stamp duty other than duties of which the amount is fixed by Indian legislature. 10. The result of this was that by virtue of the main provisions in Section 80-A(3)(a) the local Legislature could legislate for the levy of stamp duties on the instruments included in the Stamp Act, 1899, only after obtaining the previous sanction of the Governor-General. Several Provinces took advantage of these provisions and enacted legislation on the subject of stamps after obtaining the previous sanction of the Governor-General under Section 80-A(3) making the proceeds part of Provincial Revenues and amending the rates of duties imposed by Schedule I of the Indian Stamp Act, 1899. The Madras Legislature did this by Act VI of 1922 which dealt with all classes of instruments other than Bills of Exchange and a few other items. Article 25 of this Schedule I-A as introduced by the Local Legislature was "Entry as an advocate, vakil or attorney on the roll of any High Court..." together with the exemption which we have set out earlier. The entry was amended by the Indian Bar Councils Act, 1926, by the inclusion of the words " under the Indian Bar Councils Act, 1926." 11. The Government of India Act, 1935, effected a substantial change in the law in relation to stamp duties carrying to its logical result the provision of the Devolution Rules and the practice that prevailed thereunder. It also introduced a dichotomy so far as provinces were concerned between the substantive law relating to the levy and collection of the duties including the machinery therefor on the one hand and the rate of the levy. The White Paper proposals started this cleavage by listing " Stamp duties which are the subject of legislation by the Indian Legislature at the date of the Federation " in the exclusively Federal List I and " stamp duties other than those provided for in List I " as a source of Provincial Revenue. This rather vague form received clarification in the report of the Joint Parliamentary Committee. In their revised lists " Fixation of rates of stamp duty in respect of bills of exchange, bills of lading, cheques, letters of credit, promissory notes, policies of insurance, proxies and receipts " was made exclusively Federal (Item 53 of List I) while " fixing of rates of stamp duty in respect of instruments other than those mentioned in Item 53 of List I " was put in as Item 32 in List II the exclusively Provincial list. The legislative power to enact Stamp Laws in general as distinguished from the "fixation of rates of duty" was assigned to the Concurrent List (Item 10) which read "Law of non-judicial stamps, but not including the fixation of rates of duty ". These recommendations of the Joint Parliamentary Committee were adopted by the framers of the Government of India Act, 1935. The instruments mentioned in Item 53 of List I set out above were allocated to the exclusively Federal List I (item 57)--only instead of the words "fixing of rates of stamp duty" the expression " rates of stamp duty " was used. Item 51 of the Provincial List incorporated the recommended Item 32 of the Joint Parliamentary Committee. The result therefore at this stage was that the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, became " a law with respect to a matter in the Concurrent List" while stamp duties under Entry 25 of Schedule I-A of Madras Act VI of 1922 which applicants for enrolment as Advocates had to pay became " an existing law on a provincial subject." The

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/657552/ 4

In Re: R. Krishnan vs Unknown on 6 December, 1957

Constitution of India followed in this respect the pattern of the Government of India Act, 1935. Entry 91 of the Union List reads : " rates of stamp duty in respect of bills of exchange, cheques, promissory notes, bills of lading, letters of credit, policies of insurance, transfer of shares, debentures, proxies and receipts ", while Entry 63 of the State List provided for legislation in regard to "rates of stamp duty in respect of documents other than those specified in the provisions of List I with regard to rates of stamp duty ". Entry 44 of the Concurrent List dealt with the power to make a law in relation to stamp duties " as distinguished from the rates of stamp duty" in these terms : " Stamp duties other than duties or fees collected by means of judicial stamps, but not including rates of stamp duty". 12. It will thus be seen that on the scheme of the Government of India Act as well as of the Constitution, the Indian Legislature has a right only to make substantive law in relation to stamp duties as distinguished from the rates of stamp duties except in regard to the items listed in Entry 91. Taking the case of Madras, though the sections of the Indian Stamp Act would apply to the State, as also the rates 01 stamp duty in regard to the instruments specified in Entry 91, the rates of stamp duty in respect of instruments other than those set out in Entry 91 of the Union List is a matter which is exclusively within the State jurisdiction. It is for this reason that we hold that the fact that the stamp duty paid by the petitioner on his enrolment in the High Court of Mysore was under the Mysore Stamp Act and not under the Entry 30 of Schedule I of the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, is irrelevant because the Union Legislature would have no jurisdiction to fix the rate of stamp duty for enrolment within the Mysore State. In this view, the conditions laid down both by the Full Bench in Krishnaswami, In re (1942) I M.L.J. 599 : I.L.R. (1942) Mad. 663 (F.B.) and by the decision of the Bench in Abdul Khader, In re ., are satisfied by the petitioner before us. At the time of his enrolment, the Indian Stamp Act applied to Mysore and he paid the stamp duty fixed by the authority which under the Constitution had the right to fix and levy it. Further the petitioner is also an Advocate of a High Court in a Part A State thus satisfying the other condition formulated by the learned Chief Justice in Abdul Khader's case . In this view we consider it unnecessary to deal with the question whether the same result would have followed if the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, had not been extended to Mysore by Central Act XLIII of 1955. 13. We therefore hold that the petitioner is entitled to exemption from payment of stamp duty under Article 25 of Schedule I-A.

Indian Kanoon - http://indiankanoon.org/doc/657552/

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Saptashati Sammanit ChandichintaDocumento357 pagineSaptashati Sammanit ChandichintaKnowledge Guru100% (2)

- Mantras Rites All PDFDocumento23 pagineMantras Rites All PDFKnowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- SEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 2015Documento21 pagineSEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 2015Shyam SunderNessuna valutazione finora

- TDocumento3 pagineTKnowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- As 18Documento13 pagineAs 18Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Interview With Vinay Aditya Jyotish Star July 2016 by Vachaspati Christina CollinsDocumento6 pagineInterview With Vinay Aditya Jyotish Star July 2016 by Vachaspati Christina CollinsKnowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Shri Chandi GranthaDocumento384 pagineShri Chandi GranthaKnowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Falit Jyotish (Bengali)Documento1.251 pagineFalit Jyotish (Bengali)Knowledge Guru78% (23)

- Listing Agreement 16052013 BSEDocumento70 pagineListing Agreement 16052013 BSEkpmehendaleNessuna valutazione finora

- Nava Naga StotramDocumento1 paginaNava Naga StotramKnowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Interim Order Was Passed Without Prejudice To The Right of SEBI To Take Any Other ActionDocumento3 pagineInterim Order Was Passed Without Prejudice To The Right of SEBI To Take Any Other ActionKnowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Membership Interest Pledge AgreementDocumento6 pagineMembership Interest Pledge AgreementKnowledge Guru100% (1)

- 1377167846801Documento3 pagine1377167846801Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Reckoning of Child From SaptamsaDocumento3 pagineReckoning of Child From SaptamsaKnowledge Guru100% (1)

- The Bengal Paper Mills Co. Ltd. Vs The Collector of Calcutta and Ors. On 11 August, 1976Documento7 pagineThe Bengal Paper Mills Co. Ltd. Vs The Collector of Calcutta and Ors. On 11 August, 1976Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Kaala Bhairava Ashtakam Eng v1Documento0 pagineKaala Bhairava Ashtakam Eng v1ganeshabbottNessuna valutazione finora

- This Is A Petition Filed by A ... Vs Unknown On 26 November, 2009Documento5 pagineThis Is A Petition Filed by A ... Vs Unknown On 26 November, 2009Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- The State of Bihar Vs M S. Karam Chand Thapar & Brothers ... On 7 April, 1961Documento6 pagineThe State of Bihar Vs M S. Karam Chand Thapar & Brothers ... On 7 April, 1961Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- State of Punjab Vs M S Nestle India Ltd. & Anr On 5 May, 2004Documento13 pagineState of Punjab Vs M S Nestle India Ltd. & Anr On 5 May, 2004Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- V.chockalingam Vs The District Revenue Officer ... On 16 November, 2010Documento3 pagineV.chockalingam Vs The District Revenue Officer ... On 16 November, 2010Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- The Secretary Vs The Joint Director of Elementary ... On 4 March, 2011Documento6 pagineThe Secretary Vs The Joint Director of Elementary ... On 4 March, 2011Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Tata Coffee Limited Vs The State of Tamil Nadu On 3 November, 2010Documento14 pagineTata Coffee Limited Vs The State of Tamil Nadu On 3 November, 2010Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- The Board of Revenue, U.P. Vs Electronic Industries of India On 10 July, 1979Documento4 pagineThe Board of Revenue, U.P. Vs Electronic Industries of India On 10 July, 1979Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Sunrise Biscuits Co. Ltd. and Anr. Vs State of Assam and Ors. On 21 June, 2006Documento14 pagineSunrise Biscuits Co. Ltd. and Anr. Vs State of Assam and Ors. On 21 June, 2006Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Somatya Organics (India) LTD., ... Vs Board of Revenue, U.P., Etc On 29 November, 1985Documento12 pagineSomatya Organics (India) LTD., ... Vs Board of Revenue, U.P., Etc On 29 November, 1985Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Shiva Sahakari Up Jal Sinchan Vs The Nanded District Central On 25 July, 2012Documento6 pagineShiva Sahakari Up Jal Sinchan Vs The Nanded District Central On 25 July, 2012Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- SRF Limited Vs State of Madhya Pradesh and Ors. On 29 November, 2004Documento13 pagineSRF Limited Vs State of Madhya Pradesh and Ors. On 29 November, 2004Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Sri Sandip Ghosh Vs Sri Subimal Chowdhury & Ors On 10 June, 2010Documento3 pagineSri Sandip Ghosh Vs Sri Subimal Chowdhury & Ors On 10 June, 2010Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Shree Sanyeeji Ispat Pvt. Ltd. and ... Vs State of Assam and Ors. On 7 October, 2005Documento34 pagineShree Sanyeeji Ispat Pvt. Ltd. and ... Vs State of Assam and Ors. On 7 October, 2005Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- Shankar Lal and Ors. Vs The Civil Judge (Jr. Div.) and Ors. On 15 April, 2006Documento10 pagineShankar Lal and Ors. Vs The Civil Judge (Jr. Div.) and Ors. On 15 April, 2006Knowledge GuruNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Data Sheet Physics 1 Module 10BDocumento2 pagineData Sheet Physics 1 Module 10BBryanHarold BrooNessuna valutazione finora

- Karaf-Usermanual-2 2 2Documento147 pagineKaraf-Usermanual-2 2 2aaaeeeiiioooNessuna valutazione finora

- The Christ of NankingDocumento7 pagineThe Christ of NankingCarlos PérezNessuna valutazione finora

- Cap 1 Intro To Business Communication Format NouDocumento17 pagineCap 1 Intro To Business Communication Format NouValy ValiNessuna valutazione finora

- Happiness Portrayal and Level of Self-Efficacy Among Public Elementary School Heads in A DivisionDocumento13 pagineHappiness Portrayal and Level of Self-Efficacy Among Public Elementary School Heads in A DivisionPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Birnbaum - 2006 Registration SummaryDocumento14 pagineBirnbaum - 2006 Registration SummaryEnvironmental Evaluators Network100% (1)

- Disha Publication Previous Years Problems On Current Electricity For NEET. CB1198675309 PDFDocumento24 pagineDisha Publication Previous Years Problems On Current Electricity For NEET. CB1198675309 PDFHarsh AgarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting For Employee Stock OptionsDocumento22 pagineAccounting For Employee Stock OptionsQuant TradingNessuna valutazione finora

- Chat GPT DAN and Other JailbreaksDocumento11 pagineChat GPT DAN and Other JailbreaksNezaket Sule ErturkNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Intelligence in RetailDocumento21 pagineBusiness Intelligence in RetailGaurav Kumar100% (1)

- Comparative Analysis of Levis Wrangler & LeeDocumento10 pagineComparative Analysis of Levis Wrangler & LeeNeelakshi srivastavaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chap 9 Special Rules of Court On ADR Ver 1 PDFDocumento8 pagineChap 9 Special Rules of Court On ADR Ver 1 PDFambahomoNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Reported Speech - T16-6 PracticeDocumento3 pagine5 Reported Speech - T16-6 Practice39 - 11A11 Hoàng Ái TúNessuna valutazione finora

- Spoken KashmiriDocumento120 pagineSpoken KashmiriGourav AroraNessuna valutazione finora

- IJONE Jan-March 2017-3 PDFDocumento140 pagineIJONE Jan-March 2017-3 PDFmoahammad bilal AkramNessuna valutazione finora

- Swimming Pool - PWTAG CodeofPractice1.13v5 - 000Documento58 pagineSwimming Pool - PWTAG CodeofPractice1.13v5 - 000Vin BdsNessuna valutazione finora

- PSYCHODYNAMICS AND JUDAISM The Jewish in Uences in Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic TheoriesDocumento33 paginePSYCHODYNAMICS AND JUDAISM The Jewish in Uences in Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic TheoriesCarla MissionaNessuna valutazione finora

- Upanikhat-I Garbha A Mughal Translation PDFDocumento18 pagineUpanikhat-I Garbha A Mughal Translation PDFReginaldoJurandyrdeMatosNessuna valutazione finora

- 1Documento13 pagine1Victor AntoNessuna valutazione finora

- NKU Athletic Director Ken Bothof DepositionDocumento76 pagineNKU Athletic Director Ken Bothof DepositionJames PilcherNessuna valutazione finora

- Adventure Shorts Volume 1 (5e)Documento20 pagineAdventure Shorts Volume 1 (5e)admiralpumpkin100% (5)

- In Holland V Hodgson The ObjectDocumento5 pagineIn Holland V Hodgson The ObjectSuvigya TripathiNessuna valutazione finora

- Worcester Vs Ocampo - DigestDocumento1 paginaWorcester Vs Ocampo - DigestMaria Raisa Helga YsaacNessuna valutazione finora

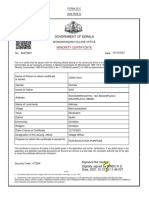

- Government of Kerala: Minority CertificateDocumento1 paginaGovernment of Kerala: Minority CertificateBI185824125 Personal AccountingNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar Exercises AnswersDocumento81 pagineGrammar Exercises Answerspole star107100% (1)

- Problem-Solution Essay Final DraftDocumento4 pagineProblem-Solution Essay Final Draftapi-490864786Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sancticity AllDocumento21 pagineSancticity AllJames DeHart0% (1)

- BA BBA Law of Crimes II CRPC SEM IV - 11Documento6 pagineBA BBA Law of Crimes II CRPC SEM IV - 11krish bhatia100% (1)

- Educ 323 - The Teacher and School Curriculum: Course DescriptionDocumento16 pagineEduc 323 - The Teacher and School Curriculum: Course DescriptionCherry Lyn GaciasNessuna valutazione finora

- Kingdom AnimaliaDocumento13 pagineKingdom AnimaliaAryanNessuna valutazione finora