Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

LIVING LIFE TO THE FULL: THE SPIRIT AND ECO-FEMINIST SPIRITUALITY - Susan Rakoczy

Caricato da

mustardandwineTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

LIVING LIFE TO THE FULL: THE SPIRIT AND ECO-FEMINIST SPIRITUALITY - Susan Rakoczy

Caricato da

mustardandwineCopyright:

Formati disponibili

http://scriptura.journals.ac.

za

Scriptura 111 (2012:3), pp. 395-407

LIVING LIFE TO THE FULL: THE SPIRIT AND ECO-FEMINIST SPIRITUALITY

Susan Rakoczy School of Religion, Philosophy and Classics University of KwaZulu-Natal Abstract

Jos Comblin, a Latin American liberation theologian, described the presence of the Spirit in five dimensions: action, freedom, speech, community and life. These provide the foundation for developing an ecological pneumatology leading to transformative praxis for the good of all creation. The insights of various eco-feminist theologians such as Heather Eaton, Ivone Gebara, Mary Grey, Elizabeth Johnson and Rosemary Radford Ruether demonstrate how Comblins five-fold pneumatology can enrich eco-feminist spirituality. Spirituality is based on experience of the Sacred, the Divine. The foundation of eco-feminist spirituality is life and liberation; it is holistic, embracing all that is created since nothing is absent from the presence of God. Themes from the Ignatian spiritual tradition of seeking and finding God in all things also provide a helpful discernment heuristic in this time of ecological challenge. Key Words: Jos Comblin, Heather Eaton, Denis Edwards, Ecofeminism, Ivone Gebara, Mary Grey, Holy Spirit, Ignatius of Loyola, Elizabeth Johnson, Jrgen Moltmann, Pneumatology, Rosemary Radford Ruether, spirituality The first chapter of the book of Genesis describes the Spirit breathing over the waters, a powerful evocation of the indwelling of the Spirit of God in all of creation. Fourteen plus billion years since the Flaring Forth separate us from that event; we now live in an era in which the survival of life on Earth is threatened because of human action and inaction. However, the development of ecofeminism and eco-feminist theology has given us new resources to use in moving from reflection to action. Eco-feminism brings together feminism and ecology into a matrix which exposes the domination of women by men and the domination of the natural world by human beings (Rakoczy 2004:300). The word itself, ecofeminisme, was coined by Francoise dEaubonne in 1974 and evolved from radical feminist thought. 1 This article uses Jos Comblins five dimensions of the presence of the Spirit as a framework in which to discuss the outlines of an ecological pneumatology which is the basis for a dynamic eco-feminist spirituality of praxis. Spirituality is based in experience and thus it is fitting to join pneumatology and eco-feminist spirituality.

Comblin: The Creative Spirit

In his book The Holy Spirit and Liberation, Jos Comblin (1923-2011), a leading liberation theologian who worked in Brazil, situates pneumatology in reference to religious

1

Ecofeminism is also linked with third-wave feminisms which pay particular attention to how class, race and culture impact on womens experiences of sexism, patriarchy and kyriarchy.

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

396

Rakoczy

experience which must bear fruit in action. He states, Experiences of the Spirit cannot be separated from positive action (Comblin 1989:20). These experiences have five dimensions and Comblin describes them in relation to the individual, communities and the Church. The first is action. Within the context of oppression of whatever kind, people begin to discover that they are subjects, not objects. This is a movement from passivity to activity, an an experience of re-birth that has to be attributed to the Spirit (Comblin 1989:21). In the context of poverty, people feel called to a vocation, to acting for change together. Their new awareness and strength is a gift of the Spirit. Comblin uses Jesus announcement of his mission in Lukes gospel as a clear example of how the Spirit calls believers to action:

The Spirit of the Lord has been given to me, for he has anointed me. He has sent me to bring good news to the poor, to proclaim liberty to captives and to the blind new sight, to set the downtrodden free, and to proclaim the Lords year of favour (Lk 4:18-19).

Denis Edwards asserts that All divine action is in the Spirit. It is the Spirit who dwells in things, enabling them to be and to become what is new (Edwards 2004:118). Jesus description of the power of the Spirit moving him to action is thus shared by all who act in the Spirit. Every initiative for liberation, for justice, for eco-justice is possible because of the indwelling of the Spirit. As Moltmann maintains, According to the biblical traditions, all divine activity is pneumatic in its efficacy (Moltmann 1985:9). The actions of the Spirit are creating, preserving, and renewing and it is Creation in the Spirit which is the theological concept which corresponds best to the ecological doctrine of creation which we are looking for and need today (Moltmann 1985:12). The second of Comblins descriptions of the Spirit is freedom. Reflecting on the Latin American context which was one of oppression and subjugation, the new freedom people are experiencing is one of self-liberation. They themselves experience liberation in the act of making themselves free; freedom is won in the struggle for liberation (Comblin 1989:24). This resonates with the South African context in which the Struggle was also a personal and collective liberation. The passage from subjugation to freedom occurs through and in the power of the Spirit and includes the emancipation of dominated peoples, the struggle for class liberation, for the liberation of nations, of women, of oppressed race, struggles for human rights and for democracy (66). Comblin uses maternal language to express this freedom: God acts among human beings as a mother; the direction of the whole of human history demonstrates the motherhood of the Spirit...A paternalistic church has forgotten the motherhood of the Holy Spirit (64, 66). Moltmann expands Comblins emphasis on freedom with his descriptions of the liberating actions and presence of the Spirit. Liberating faith first frees the person from sin and inner slavery in order to live in Christs liberating freedom. This freedom means being possessed by the divine energy of life, and participation in that energy (Moltmann 1992:115). Paul enunciates a basic discernment principle, Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom (2 Cor 3:17). Moltmann asserts that the discipleship of Jesus and the liberating Spirit act together, in order to lead people into true freedom (1992:121).

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

Living Life to the Full: The Spirit and Eco-feminist Spirituality

397

Therefore the often common perspective that personal spirituality and action for justice are two separate realms is totally erroneous. The Spirit of freedom sets individuals and communities free so that they can love others, enhancing and deepening social freedom, which is named as solidarity. It is this freedom freedom as community, or sociality which is able to heal the wounds which domination has inflicted and still inflicts (Moltmann 1992:119), a domination caused by the prevalence of the individual capitalistic model which exalts individual freedom at the expense of the community. Liberating hope is the creative passion for the possible (119), focused on the future of creative possibilities both personal and social. The interweaving of these two dimensions constantly changes since the web of relationships in which we live in the presence of the Spirit is always open, always creative. Thirdly, the Spirit empowers new speech. The poor who were afraid to speak and who thought that they had nothing to say realised that they can share what the Word of God means to them, can speak to God in their own words, can demand their rights from government authorities. The Spirit who searches the depths of everything (1 Cor 2:10) is present in the deepest dimension of the person and thus speech springs from the energies hidden in the secret depths of the psyche; it is being brought back to life (Comblin 1989:27). Comblin comments that in Pauline theology also the power of the Spirit is prominently shown in speech (68). Paul himself was conscious of this when he declared, In my speeches and the sermons which I gave, there were none of the arguments that belong to philosophy; only a demonstration of the power of the Spirit (2 Cor 2:4). This sign of the presence of the Spirit is clear today in the new language of ecology and ecofeminism. Prophetic voices denounce the destruction of the planet through human selfishness and announce that there must be a new way for humanity to live together in order that life will flourish. Fourthly, the Spirit creates community and its formation is the proper work of the Spirit, the effect of freedom and liberating speech (Comblin 1989:71). Community needs to grow organically from the people. Comblin criticises efforts of the clergy to set up small communities in parishes according to geography because true community develops organically by the members. Modern values of egoism and selfishness make the formation of community difficult except amongst the poor and he comments that in rich circles they are virtually unthinkable, and they are difficult enough in middle-class circles. (73). This community-making action of the Spirit is seen in ecumenical dialogue and encounters, in inter-religious dialogue and action on behalf of justice. The Spirit breaks down boundaries of race, class, and religion, creating new communities of conscience and praxis. The Spirit creates community not only amongst humanity but also creates the community of all created things with God and with each other (Moltmann 1985:11). The reality that In God we live and move and have our being (Acts 17:28) describes the intimacy of everything from quantum particles to the furthest galaxy. Creation is one reality. Mary Grey depicts this as the field force of mutuality, itself wider than all established religions, which discloses new epiphanies of connection between the human and the non-human. (Grey 2003:112). Lastly, Comblin names life as a constitutive dimension of the presence of the Spirit. Each of the other four dimensions is intertwined with life: Freedom brings life, speech brings life, action brings life, community brings life (Comblin 1989:73). The Spirit as life-

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

398

Rakoczy

giver and renewer of life says that death will not triumph since the dynamic of the Paschal Mystery death to life is stronger than all injustice and oppression. The Spirit leads us to true life by helping us to experience the reality of God in Christ. Life-Giver is an early name for the Spirit and is found in the creeds in which the Spirit is affirmed as Lord and Giver of Life. Various Scripture texts such as Jesuss dialogue with Nicodemus (John 3) stress that life in Christ is new life in the Spirit and in his conversation with the Samaritan woman he offers her living water that will be a spring of eternal life (Jn 4:14). For Paul, it is the Spirit that gives life (2 Cor 3:6). Life in community flourishes when people discover that they live precisely in proportion to the degree to which they allow themselves to become involved in the community and its mission (Comblin 1989:30). Life is not measured in the quantities of new things one acquires but in the depth of new relationships with God in Christ and with others. The Spirit makes real Christs promise of the fullness of life (Jn 10:10). Edwards stresses that the Spirit gives life to all of creation since She is the dynamic presence of God to creatures, enabling them to exist and to evolve by embracing them in relationship with the divine communion and drawing them toward their future in God (Edwards 2006:37). All that lives has energy. Elizabeth Johnson names Spirit-Sophia as the source of transforming energy among all creatures. She initiates novelty, instigates change, transforms what is dead into new stretches of life (Johnson 1992:135). Wherever there is new life from the birth of a baby to the freshness of spring to actions for justice which bring about new relationships there is the Spirit. These five dimensions of the presence and action of the Spirit action, freedom, speech, community and life provide appropriate hermeneutical themes with which to develop an ecological pneumatology.

Towards an Ecological Pneumatology

While in one sense all theological themes are important, at certain times one may become particularly crucial. This was apparent in the 16th century at the time of the Reformation when justification by faith and the relation of Scripture and tradition were contested by Lutherans, Catholics and Calvinists. In our era, characterised by immense ecological challenges, pneumatology the theology of the Holy Spirit is beginning to assume such a theological pride of place. In Western Christianity the Spirit has often been neglected, in contrast to the theology of the Eastern Church which has always had a distinct pneumatological focus since it is rooted in the works of Athanasius, Cyril of Alexandria and Basil the Great. The Orthodox tradition pays more attention to the Holy Spirit both in the doctrine of salvation and in ecclesiology (Krkkinen 2002:12). The worldwide Pentecostal movement has also given renewed prominence to the person and work of the Spirit. Awareness of the presence and activity of the Spirit which has no limits is especially needed in our era. As humanity grapples with ways to preserve life on the whole Earth and to live the insights that everything is connected in God, the insights of an ecological pneumatology which can lead to a spirituality of engagement and care for creation are urgently needed. Moltmann describes the theological challenges of our times and argues that theological traditions cannot merely adapt they must rediscover their own original truth, which has been distorted or suppressed through an ideology of the subjection of nature (Moltmann 1985:12). A renewed pneumatology will be the basis for an ecological theology of creation and an eco-feminist spirituality focused on life to the full. The Spirit as the green face of

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

Living Life to the Full: The Spirit and Eco-feminist Spirituality

399

God (Grey 2003:11) is creatively and lovingly present to all creatures and thus the earth, then, has a sacramental character: it symbolizes the divine that is present in it (Edwards 2004:128). All creatures are important in the web of life; none are forgotten in the Spirit even though humanity often continues to see creation as instruments for human use. Edwards asserts that the interrelated systems that support life on earth ... can be understood as very much the domain of the life-giving Breath of God (128). She who is Spirit-Sophia is the source of transforming energy among all creatures (Johnson 1992:135), from the awakening of the earth in spring to initiatives for the transformation of human structures and communities. The five-fold action of the Spirit which Comblin describes thus is the basis of an ecological pneumatology. His prism is a discernment hermeneutic through which we can interpret contemporary ideas and events. Action: Where and how is the Spirit leading humanity to actions that will demonstrate loving care for our fragile planet? Freedom: How is the Spirit liberating humanity from a perspective that sees the earth and all that lives in it as instruments for human use? How is humanity recognising that true freedom does not mean acquiring more and more stuff but is an inner transformation of the heart and mind? Speech: Who is speaking and writing the bold words that call humanity to recognise that we live together on this planet as one human community? How is this message being communicated? The growth of various forms of social media are binding humanity together in ways never before experienced as ideas quickly spread around the globe. Community: What new forms of ecological communities are being created? They do not have to have religious affiliations since the Spirit acts beyond the borders of religious communities. Where are the communities of care for the earth in ones area? country? continent? Life: How are people energized in new ways to recognise that life is both tough and fragile and that humanity must act on behalf of life in all its multiple forms?

Eco-feminist Theology

We move now from Comblins creative interpretation of the Spirit to considering how the insights of eco-feminist theology can assist the development of a theological vision which focuses on life to the full for all. Ecofeminism brings together feminism and ecology into a matrix which exposes the domination of women by men and the domination of the natural world by human beings (Rakoczy 2004:300). The goal of ecofeminism is a fundamental transformation of consciousness of how we humans understand ourselves, our relationships with others and with all of creation. Ivone Gebara of Brazil describes how she abandoned my exclusively androcentric (human-centered) and androcentric (male-centered) view of the world. I have begun, then, to feel the life within me in a different way (Gebara 1999:vi). Mary Grey concurs and asserts that this as a radical epistemological shift because it involves knowing ourselves as part of the web of life, in communion and interdependent with all living things (Grey 2003:130). This change involves three dimensions. We are to rethink our understanding of the world, moving from a subject-object stance to one which privileges the experience of the poor and marginalized who are most affected by ecological degradation. Grey states that eco-feminist theology is re-thinking the world

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

400

Rakoczy

from the basis of its most marginal categories poor people, indigenous peoples, women and children who, of course, are also present in the first two categories (134). Secondly, we are called to re-think the human person. A Western view of the person has focused on the individual and his or her autonomy and freedom. The traditional African perspective locates the individual in the community and asserts that a person is a person through others. But both are inadequate interpretations in the light of the ecological crisis. The person in community must be seen in relation to the environment and all of creation. We are not separate from the amazing fecundity of life in all its forms; we are intimately related to all that is created. Eco-feminist theology challenges humanity to a new type of kenosis. Grey asserts that:

...knowing the world is acquiring this reverence for the smallest life form. It is taking seriously Christs call to lose self in order to find it. The self we will find will be far beyond the narrow confines of narcissistic individualism.

This will involve both men and women undertaking shared responsibility for sustaining life a life that embraces our own species in relation to the environment (2003:134). Thirdly, we are called to re-think the mystery of God. God is not over and above creation, but at its heart as its Source and within as the Loving Presence that make possible all that exists. A panentheistic understanding of God God within creation opens up new possibilities for theological reflection. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin wrote:

God, in all that is most living and incarnate in Him, is not withdrawn from us beyond the tangible sphere; He is waiting for us at every moment in our action, in our work of the moment. To repeat, by virtue of the Creation, and still more, of the Incarnation, nothing sic here below is profane to those who know how to see (Teilhard de Chardin 1960:33, 35).

We can expand Rosemary Radford Ruethers now classic principle of feminist theology the promotion of the full humanity of women (Ruether 1982, 1993:18) to encompass all of creation. The foundation of eco-feminist theology is therefore the promotion of the dignity and worth of all of creation. Whatever denigrates the value of creation is not of God; what does enhance life is of the Spirit of God for the Spirit is Life. All of creation is one circle of life which lives in the Spirit. Referring to the Trinity and using the symbol of Breath (a traditional image of the Spirit), Gebara speaks of the profound intuition that all of us participate, along with everything that exists, in the same Breath of Life...we all share the same breath (Gebara 1999:154). Eco-feminist theology rejects the stewardship model of the relation of humans and creation because it continues a hierarchical perspective. Humanity remains over and against creation. Johnson comments, Yet it misses the crucial aspect of human dependence upon that which we steward (Johnson 1993:30). She argues that a kinship model more accurately reflects the reality of interdependence. It sees human beings and the earth with all its creatures intrinsically related as companions in a community of life. Because we are all mutually interconnected, the flourishing or damaging of one ultimately affects all. This kinship attitude does not measure differences on a scale of higher or lower ontological dignity but appreciates them as integral elements in the robust thriving of the whole (30). The core insights of eco-feminist theology provide a solid foundation for the next step in our theological exploration of the relationship between pneumatology and eco-feminist theology which is understanding the meaning of eco-feminist spirituality.

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

Living Life to the Full: The Spirit and Eco-feminist Spirituality

401

Principles of Eco-feminist Spirituality

In contemporary life, the word spirituality is amazingly elastic, since it stretches to include everything from solitary spiritual practices outside a formal religious tradition to the core understandings of religious experience within a religion such as Christianity or Buddhism. Spirituality is related to the desire for self-transcendence, for the more beyond the mundane. It is not an exclusively religious term but in this paper will be framed in religious language. Two Asian women, Mary John Mananzan and Sun Ai Park, have beautifully described spirituality as the shape in which the Holy Spirit has molded herself into ones life (Mananzan and Park 1988:77). Sandra Schneiders stresses that Christian spirituality is essentially Trinitarian, christocentric and ecclesial (Schneiders 1986, 1996:31). For Christian women, this means that these symbols of their faith must be reinterpreted in lifeaffirming ways. Elizabeth Johnson provides a helpful interpretation of the Spirit which enriches our understanding of ecofeminism and spirituality. She asserts that as the continuous creative origin of life the Creator Spirit is immanent in the historical world (Johnson 1993:42). This describes panentheism, in which all of creation exists in God. This relationship is not strictly symmetrical because God and the world are different, yet the Spirits encircling indwelling weaves a genuine solidarity among all creatures and between God and the world (43). An eco-feminist spirituality is rooted in the Spirits presence in all of creation. Our earth is damaged through human action and the refusal to act and in urgent need of healing. The Spirit is the healing presence and power which can make that which is broken whole, that which is wounded whole and firm. The Spirit is at work to heal the damaged earth, violent and unjust social structures, the lonely and broken heart (43). Eco-feminist spirituality speaks of earth healing and this understanding of the Spirit gives it a profound theological foundation. The Spirit is ever-active, ever-alive in the world, in the human heart, in every creature. Johnson uses her preferred image of kinship to emphasise that the Spirit characteristically sets up bonds of kinship among all creatures, human and non-human alike, all of whom are energised by this one Source (44). The slow growth of an ecological consciousness in humanity is a sign of the Spirits presence of uniting people across cultures and societies in order to care together for the Earth, our only home. The foundation of Christian feminist spirituality is life and liberation, flowing from Jesus assertion that I have come that they might have life and have it to the full (Jn 10:10). We can describe this spirituality as:

...an approach which seeks and finds God in all the circumstances of life, affirms life and growth in others, works with others to bring a greater fullness of life wholeness and right relationships into every situation and structure of culture and society, including the church (Rakoczy 2004:374).

It is a holistic approach since nothing that exists is absent from the presence of God in whom we live and move and have our being (Acts 17:28). Christian feminist spirituality interprets religious experience within a framework of integration and wholeness. It rejects any kind of dualism: body and spirit, earth and heaven, humanity and creation. Because Christian faith and spirituality have been infected for 2000 years with a suspicion of the body, particularly female bodies, this negative attitude has

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

402

Rakoczy

often been transferred to created reality. Much of the literature of Christian spirituality has exalted the spirit over the world and has warned of the dangers of becoming immersed in worldly things to the detriment of ones soul. In the Roman Catholic tradition, this perspective has only begun to lessen because of the positive perspective of the Second Vatican Council. The opening paragraph of the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes) dramatically express this radical shift: The joy and hope, the grief and anguish of the people of our time, especially of those who are poor or afflicted in any way, are the joy and hope, the grief and anguish of the followers of Christ as well (GS 1). Another important dimension of Christian feminist spirituality is its emphasis on justice, understood as right relationships, and community. Justice for the whole Earth Community with all that humanity shares the planet stretches and expands the understanding of relationships. We can echo the insights of Francis of Assisi who addressed creation as Brother Sun and Sister Moon, Brothers Wind and Air, Sister Fire and Mother Earth and knew that he was part of a much larger community than only human persons. Christian feminist spirituality also breaks down the dichotomy between personal and social transformation. The choice is not personal holiness or commitment to justice but both simultaneously for they are the two feet of love which Catherine of Siena (1347-1380) knew from her own experience. Just as it is very difficult to hop on one foot for even a few minutes, our relationship with God and one another is distorted if either prayer or action is preferred against the other. 2 These dimensions are further enfleshed when they become foundations of eco-feminist spirituality. Heather Eaton emphasises that the ecological dimension of spirituality rests on the presupposition that the earth is sacred, and that the immanent presence of the sacred within nature evokes respect for all living things (Eaton 2005:86). Both religious and nonreligious forms include interconnectedness, webs of relations, interdependence, mutually enhancing patterns of existence together with interest in cosmology meaning a sense of the whole, the unfolding of the universe, ultimate source of revelation (86). Since ecofeminism and its spiritual practice are still unfolding, there is a sense of profound searching as persons discover the Sacred in creation. Rosemary Radford Ruether asserts that ecological spirituality needs to be built on three premises: the transience of selves, the living interdependency of all things, and the value of the personal in communion (Ruether 1992:250). The first is not the traditional injunction to self-denial which has not served women well, since they often struggle to have a strong sense of self but rather an acceptance of the fact that we have but a short time on earth and then through death our bodies disintegrate into organic matter, to enter the cycle of decomposition and recomposition as other entities (252). Echoing Johnsons stress on kinship with the earth, Ruether describes this kinship as global, which also spans the ages, linking our material substance with all the beings that have gone before us on earth and even to the dust of exploding stars (252). She invites us to compose new psalms and prayers which celebrate this cosmological kinship. Each creature is, like ourselves, somehow personal, as we recognise the singularity of a flower, an insect, an animal. The gift of recognising their singularity increases the sense of

2

This is the thesis of Susan Rakoczy, Great Mystics and Social Justice: Walking on the Two Feet of Love (New York: Paulist Press, 2006) in which the lives of mystics such as Catherine of Siena, Ignatius of Loyola, Evelyn Underhill, Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day are analysed to learn how they balanced prayer and social commitment.

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

Living Life to the Full: The Spirit and Eco-feminist Spirituality

403

kinship and so compassion for all living things fills our spirits, breaking down the illusion of otherness (252). Ruether gives a number of suggestions for ways to live a feminist ecological spirituality. The first dimension concerns the personal and the call to conversion from our patterns of consumption, our internalization of the power of male authorities, our disregard for the sacredness of all of creation. She asserts that we need therapies and spiritualities of inner growth in order to learn how to be, rather than to strive (269). We need time to be with nature, to pay close attention to what is around us, and to allow nature to heal our fractured, competitive, consumerist selves. But individual transformation is not sufficient since we are persons in community. Communities are called to create new kinds of liturgies in which persons mourn together for violated lives, to midwife healing and new birth, and to taste a new creation already present (270). These liturgies must also be public events to protest against the systems which are strangling our earth and which also tantalise others with the hope of something different. This calls for an examination of conscience to see how our life-style harms the planet and what efforts we can personally make to live a life which is healthy for all. Ruether insists that the personal is linked to political and so a feminist ecological spirituality includes actions to influence the life of the larger community. Political action takes different forms, depending on the context, but often it is best to begin at the local level where changes can be more obvious. All of these actions demonstrate a deep love which means we remain committed to a vision and to concrete communities of life now matter what the trends may be (273). The strands of an eco-feminist spirituality of commitment to life and liberation, reverence for the body and created reality, work for justice and right relationships, and the intertwining of the personal and political weave themselves together into an unfinished tapestry of hope for a more abundant life for all.

The Praxis of a Pneumatic Eco-feminist Spirituality

The next step of our analysis is to integrate Comblins five dimensions of the presence of the Spirit of God with the evolving understandings of eco-feminist spirituality. Johnsons three-fold interpretation of the Spirit who is immanent in creation, who heals that which is broken and who unites the human community to care for the earth interfaces gracefully with Comblins descriptions of the presence of the Spirit. The Spirit calls all people of faith and of conscience to action, action which is supremely urgent. There is no time to waste; words and documents of good intent must be translated into transforming action. This demands a radical change in consciousness both individually and collectively which is premised on the sacredness of creation because of the Spirits indwelling. The oft-quoted mantra think globally and act locally takes on new meaning when the Spirit pushes and prods humanity to varied and diverse actions. The Spirit creates freedom. Women and nature both stifled and devalued by patriarchal domination need to experience the freedom of the Spirit. Structures of gender oppression and mindsets of domination of the earth are not signs of the Spirit of God. This freedom encompasses the mind, heart and imagination as humanity experiences a profound liberation from habits of thinking which enslave others and nature. The Spirit creates new speech. At Pentecost the apostles, who spoke in one language, presumably Aramaic, were understood by people from diverse linguistic communities. The

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

404

Rakoczy

message of salvation and liberation in and through the Risen Christ was heard clearly and people responded with faith. The language of eco-feminist spirituality contains new terms and ideas that of the unity of humanity and creation, of the urgency of our ecological crisis, of the presence of the Spirit in creation which need to be translated across cultures so that all can understand and act. Eco-feminists speak on behalf of creation who do not have voices to communicate with humanity but who demonstrate the worsening ecological crisis through their deaths and change of habitats because of drought and rising temperatures that they also experience trauma. Ecological speech is Spirit-inspired speech for the good of all. The Spirit creates community. At this time around the world new communities of faith and conscience are being created by people who experience the call to act for the good of creation and the future of the planet. Sometimes these are communities rooted in a religious tradition. An explicit faith tradition such as Christianity gives the ecological community language to express their vision and motivation. Inter-faith and secular communities are also signs of the Spirit as community-builder. All of these communities seek to translate their sense of call on behalf on the Earth into praxis, into transforming action. Lastly, the Spirit creates life life for all and to the full. In the Nicene Creed Christians name the Spirit as life-giver who is the unceasing, dynamic flow of divine power that sustains the universe, bringing forth life (Johnson 1993:42). We see the forces of death and destruction ranged against the earth itself because of human action and inaction, the oppression of women and children, the stigma that clings to those infected and affected by HIV/AIDS, the abuse of the most vulnerable. As powerful as these signs of social sin are, the Spirits presence is yet more pervasive and transforming. Eco-feminist spirituality invites all to look for, nourish and celebrate the fullness of life wherever it is evident. Where life is diminishing all persons must join in fanning into flame the smallest signs of life.

Discerning the Spirit Today

Where is the Spirit active today? Comblins five signs of the presence of the Spirit action, freedom, speech, community and life are a very helpful discernment heuristic in this time of ecological crisis and challenge. In addition, themes from the Ignatian spiritual tradition provide practical assistance to discern the presence of the Spirit from the perspective of eco-feminist spirituality. The foundation of Ignatian spirituality as developed by Ignatius of Loyola 1495-1556 is the challenge to seek and find God in all things. In his letters, Ignatius frequently used these phrases: to seek in all things the presence of God, to find God in all things, to live with God ever before ones eyes, and to always direct ones self to God (Rakoczy 2006:60). In his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius developed Rules for Discernment to guide persons and communities in decision-making. Especially important is his interpretation of consolation and desolation which is built on the awareness of ones feelings and the direction that they are leading a person. Consolation is a positive affective experience of joy and love which increases faith, hope and love (SpEx 316). Desolation is strikingly different since it is darkness and confusion of ones spirit which leads to a weakening of faith, hope and love (SpEx 317).

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

Living Life to the Full: The Spirit and Eco-feminist Spirituality

405

Personal Desolation and Consolation

As we consider the ramifications of global warming and climate change, there are many occasions in which desolation of spirit may occur. The facts of global warming and the extent of the damage to Earth as a whole, to other human communities, to all other living beings and the oceans, atmosphere, etc may easily lead to feelings of horror and helplessness. The immensity of the problems can also lead to a loss of energy and a reluctance to act. One may ask, Who am I that my actions can have a significant effect? I am just one of seven billion plus people riding the earth together. The reality is that all of us feel that our life is indeed very significant and will go to almost any lengths to protect it since self-preservation is our strongest instinct. The most serious sign of desolation is the loss of hope. The future now appears in peril and the stability of the earth is now under threat. What can we hope for if the human community may actually be reduced to a few thousand women and men? Desolation in the light of the knowledge of climate change and its effects can so weaken faith, hope and love that one may indeed conclude that an awful, apocalyptic fate is humanitys future. Since consolation is the opposite affective experience in every way, the effects of the knowledge of the ecological crisis are strikingly different. Ignatius emphasises that consolation is an increase of faith, hope and love that moves the person closer to God and gives him or her deeper peace. Faith strengthens in the profound conviction that we are not alone on the earth but that God who created humanity and all of creation animate and inanimate will never abandon us (Is 49:15). The power of sin and selfishness, seen graphically now in the possible destruction of so much of life on earth because of human choices, moves a person to repentance and the desire to change their way of life. Hope increases as radical trust in God and in the goodness of others also created by God. Love is energy for maintaining and strengthening relationships with God and with others. It moves us outward, beyond ego needs and ego fears, to nurture these relationships which are utterly essential to us as human persons. Because a person feels deeply this connectedness with all of Gods creation, they are willing to make changes in their life to preserve life and help it to flourish on earth, our only home.

Communal Desolation and Consolation

How may communal desolation be experienced? In some ways it is a larger, deeper, more profound experience of personal desolation: horror, helplessness and lack of hope. The increasingly alarming predictions of our planets future are truly frightening and we can increase the horror and helplessness by focusing on the speed of the changes and the worstcase scenarios of the effects of global temperature changes. A kind of paralysis can take hold in which faith communities see no way to act effectively for a future of hope for the next generations. But communal desolation is more than horror and helplessness. It is the withdrawal from the wider community, from shared responsibility for the future, from concerted action. It is a weakening of faith, hope and love as Ignatius describes desolation in profound ways. Faith degenerates into a kind of magic in Gods action to rescue us; hope is a misplaced conviction that radical change is not necessary; love as responsibility disappears as we think me first. Fortunately, communal consolation the increase of faith, hope and love is also possible and real. Because these are communal experiences, they result from our interaction with

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

406

Rakoczy

one another. It is hope expressed as solidarity, which is a new moral category of felt interdependence,... a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good (SRS 38). 3 The experience of solidarity gives each person the confidence to think globally and act locally to prevent the most dire scenarios from becoming reality. The faith and hope of others supports each person and moves them from desolation to consolation, since the faith and hope of all together is truly greater than the sum of each persons experiences. The increase of love which inflames our hearts with love for God (SpEx 316) is also a social experience which binds us together profoundly, both as disciples and as witnesses. The witness of social love, of a new asceticism of Christian communities, of countercultural actions to begin to save a planet in peril, demonstrates to the wider human community that religious faith is shown most concretely in actions for the good of all of humanity today and into the future.

Conclusion

The Spirit is both transcendent and immanent and Her immanence is experienced in diverse ways. Comblins five ways of discerning the Spirit through action, freedom, speech, community and life provide a foundation for a pneumatic eco-feminist spirituality. This spirituality challenges women and men to view creation with a new vision of interdependence and kinship, to be committed to life and liberation for all and to thinking globally and acting locally. The resources of the Ignatian spiritual tradition which emphasise discernment provide helpful guidelines for integrating the personal and the political as persons and communities seek to find God in all things, including our ecological crisis. All persons of conscience are continually challenged to strengthen and deepen their ecological commitment and to develop new, creative ways of ecological praxis.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Comblin, J 1989. The Holy Spirit and Liberation (translated by P Burns). Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books. Eaton, H 2005. Introducing Eco-feminist Theologies. London and New York: T&T Clark International. Edwards, D 2004. Breath of Life: A Theology of the Creator Spirit. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books. Edwards, D 2006. Ecology at the Heart of Faith. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books. Gaudium et Spes, The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, in A Flannery OP (ed.), Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents, volume 1 (rev. edition). Northport, NY: Costello Publishing Company, 1988:903-1001. Gebara, I 1999. Longing for Running Water: Ecofeminism and Liberation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. Grey, MC 2003. Sacred Longings: Eco-feminist Theology and Globalization. London: SCM Press.

3

http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/encyclicals/documents/_hf_jp_ii_enc_30121987_sollicitudorei-socialis.en.html. Accessed 15 September 2012.

http://scriptura.journals.ac.za

Living Life to the Full: The Spirit and Eco-feminist Spirituality

407

Johnson, EA 1993. She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discourse. New York: Crossroad. Johnson, EA 1993. Women, Earth and Creator Spirit. New York: Paulist Press. Krkkinen, V-M 2002. Pneumatology: The Holy Spirit in Ecumenical, International and Contextual Perspective. Ada, Michigan: Baker Academic. http.books.google.co.za.books?isbn=080102448X. Accessed 8 November 2012. Mananzan, MJ and Park, SA 1988. Emerging Spirituality of Asian Women, in V Fabella and M Oduyoye (eds.), With Passion and Compassion: Third World Women Doing Theology. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books. 77-88. Moltmann, J 1985. God in Creation: An Ecological Doctrine of Creation (translated by M Kohl). London: SCM Press Ltd. Moltmann, J 1992. The Spirit of Life (translated by M Kohl). Minneapolis: Fortress Press. Rakoczy, S 2004. In Her Name: Women Doing Theology. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. Rakoczy, S 2006. Great Mystics and Social Justice: Walking on the Two Feet of Love. New York: Paulist Press. Ruether, RR 1983, 1993. Sexism and God-Talk. Boston: Beacon Press. Ruether, RR 1992. Gaia and God: An Eco-feminist Theology of Earth Healing. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco. Schneiders, SM 1986, 1996. Feminist Spiritual Spirituality: Christian Alternative or Alternative to Christianity? in JW Conn (ed.), Womens Spirituality: Resources for Christian Development (2nd edition). New York: Paulist Press. 30-67. Teilhard de Chardin, P 1960. The Divine Milieu. New York and Evanston: Harper & Row, Publishers.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Negotiating Peace: North East Indian Perspectives on Peace, Justice, and Life in CommunityDa EverandNegotiating Peace: North East Indian Perspectives on Peace, Justice, and Life in CommunityNessuna valutazione finora

- BID06 AssignmentDocumento5 pagineBID06 AssignmentJune Cherian KurumthottickalNessuna valutazione finora

- Biblical Hermeneutics Lesson 1Documento3 pagineBiblical Hermeneutics Lesson 1Jaciel CastroNessuna valutazione finora

- Paul Speaks: The Prison Letters: The Lost Books Series, #1Da EverandPaul Speaks: The Prison Letters: The Lost Books Series, #1Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Plight of Christians in The Middle EastDocumento35 pagineThe Plight of Christians in The Middle EastCenter for American ProgressNessuna valutazione finora

- Doing Theology in the New Normal: Global PerspectivesDa EverandDoing Theology in the New Normal: Global PerspectivesNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Rights and Christian MissionDocumento12 pagineHuman Rights and Christian MissionDuane Alexander Miller Botero100% (1)

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Man and His MissionDocumento5 pagineDietrich Bonhoeffer, The Man and His MissionJoseph WesleyNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Social SinDocumento19 pagineUnderstanding Social SinJenn TorrenteNessuna valutazione finora

- Missiology in A Pluralistic WorldDocumento14 pagineMissiology in A Pluralistic WorldynsanchezNessuna valutazione finora

- The Relevance of Juergen Moltmann's Trinitarian Theological Anthropology To The Problem of The Behavioural Custom of Masking 2014-9-19Documento70 pagineThe Relevance of Juergen Moltmann's Trinitarian Theological Anthropology To The Problem of The Behavioural Custom of Masking 2014-9-19Tsung-I HwangNessuna valutazione finora

- Feminist Theology - Women's MovementDocumento2 pagineFeminist Theology - Women's MovementIvin Paul100% (1)

- Feminist EpistemologyDocumento13 pagineFeminist EpistemologyJoyal Samuel JoseNessuna valutazione finora

- Feminist Christology and Pneumatology - Point V - KingslyDocumento3 pagineFeminist Christology and Pneumatology - Point V - KingslyTuangpu SukteNessuna valutazione finora

- Divine Presence and Divine Action: Reflections in The Wake ofDocumento4 pagineDivine Presence and Divine Action: Reflections in The Wake ofspiltteethNessuna valutazione finora

- Augustine's Account of Evil As Privation of GoodDocumento13 pagineAugustine's Account of Evil As Privation of GoodPhilip Can Kheng Hong100% (2)

- 1 18 Muslim Christian Dialogue CSC Volume 2 Issue 1 PDFDocumento18 pagine1 18 Muslim Christian Dialogue CSC Volume 2 Issue 1 PDFAasia RashidNessuna valutazione finora

- Book Review - Global Theology in Evangelical Perspective.Documento7 pagineBook Review - Global Theology in Evangelical Perspective.Debi van DuinNessuna valutazione finora

- Evangelism and Missions: Case StudyDocumento22 pagineEvangelism and Missions: Case StudyFiemyah Naomi100% (1)

- N T Wright Hermeneutic Exploration PDFDocumento24 pagineN T Wright Hermeneutic Exploration PDFAlberto PérezNessuna valutazione finora

- Monasticism's Spiritual Pursuits of Renouncing Worldly LifeDocumento7 pagineMonasticism's Spiritual Pursuits of Renouncing Worldly LifeCarlo Medina MagnoNessuna valutazione finora

- James Gustafson - Place of Christian Scripture in Ethics!!Documento27 pagineJames Gustafson - Place of Christian Scripture in Ethics!!Rh2223dbNessuna valutazione finora

- Re Envisioning Tribal Theology EngagingDocumento21 pagineRe Envisioning Tribal Theology Engagingsimon pachuauNessuna valutazione finora

- Niebuhr, Reinhold - Beyond TragedyDocumento131 pagineNiebuhr, Reinhold - Beyond TragedyAntonio GuilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Christianity and Culture (Acts 15:1-31Documento15 pagineChristianity and Culture (Acts 15:1-31AlbertJnBaptisteNessuna valutazione finora

- Rodney Stark Reconstructing Rise of Christianity WomenDocumento17 pagineRodney Stark Reconstructing Rise of Christianity WomenRodolfo100% (2)

- Betcher, Sharon v. - Becoming Flesh of My Flesh - Feminist and Disability Theologies On The Edge of Posthumanist DiscourseDocumento13 pagineBetcher, Sharon v. - Becoming Flesh of My Flesh - Feminist and Disability Theologies On The Edge of Posthumanist Discoursejen-leeNessuna valutazione finora

- My Assignment 1 PsDocumento11 pagineMy Assignment 1 Psjunaid bhattiNessuna valutazione finora

- 03 Recent Pauline StudiesDocumento12 pagine03 Recent Pauline StudiesKHAI LIAN MANG LIANZAW100% (1)

- The Environment - Why Christians Should CareDocumento3 pagineThe Environment - Why Christians Should CareWorld Vision Resources100% (1)

- Mission and Soteriological UnderstandingDocumento8 pagineMission and Soteriological UnderstandingRin KimaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pauline Thoughts Clas NotesDocumento8 paginePauline Thoughts Clas Notesfranklin cyrilNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Cor 13 Exegesis PaperDocumento11 pagine1 Cor 13 Exegesis PaperNoah BauerNessuna valutazione finora

- Cultural Anthropology Reading - Mission and AnthropologyDocumento9 pagineCultural Anthropology Reading - Mission and AnthropologylidicemeyerNessuna valutazione finora

- Muhammad Iqbal and Environmental Ethics-Talk May14 TurkuDocumento12 pagineMuhammad Iqbal and Environmental Ethics-Talk May14 TurkuibrahimNessuna valutazione finora

- A Theological Investigation Into The Fate of Unevangelised People - Lalhuolhim F. TusingDocumento1 paginaA Theological Investigation Into The Fate of Unevangelised People - Lalhuolhim F. TusingLalhuolhim F. TusingNessuna valutazione finora

- Union Biblical Seminary, Bibvewadi Pune 411037, Maharastra Presenter: Ato Theunuo Ashram MovementDocumento4 pagineUnion Biblical Seminary, Bibvewadi Pune 411037, Maharastra Presenter: Ato Theunuo Ashram MovementWilliam StantonNessuna valutazione finora

- Caste System in India - Origin, Features, and Problems: Clearias Indian Society NotesDocumento15 pagineCaste System in India - Origin, Features, and Problems: Clearias Indian Society NotesMudasir ShaheenNessuna valutazione finora

- Kim Christian - Making Disciples of Jesus Christ 2017Documento348 pagineKim Christian - Making Disciples of Jesus Christ 2017Joel David Iparraguirre Maguiña100% (1)

- Importance of Jerusalem Council TodayDocumento4 pagineImportance of Jerusalem Council TodayTintumon DeskNessuna valutazione finora

- Decolonizing The Body of ChristDocumento28 pagineDecolonizing The Body of ChristAhmad SajidNessuna valutazione finora

- Jesus and PoorDocumento6 pagineJesus and PoorNimshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Bateman Ps110 BSDocumento16 pagineBateman Ps110 BSCori GalloNessuna valutazione finora

- Theology of Mission - Lecture 4Documento64 pagineTheology of Mission - Lecture 4Cloduald Bitong MaraanNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesslie Newbigin's Influence on Mission TheologyDocumento7 pagineLesslie Newbigin's Influence on Mission TheologyRomuloFerreira19Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Nature and Dynamics of Crisis ExperienceDocumento2 pagineThe Nature and Dynamics of Crisis ExperienceDuan Gonmei100% (1)

- 1 B Re Imagining Org, Admin, Polity, MNGMT, Constitution andDocumento20 pagine1 B Re Imagining Org, Admin, Polity, MNGMT, Constitution andPhiloBen KoshyNessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophy PaperDocumento32 paginePhilosophy Paperapi-312442464Nessuna valutazione finora

- Minjung Theology A Korean Contextual The PDFDocumento11 pagineMinjung Theology A Korean Contextual The PDFRoberto HamonanganNessuna valutazione finora

- Prophetic Legacy MLKDocumento40 pagineProphetic Legacy MLKJose María Segura SalvadorNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 SyllogismDocumento14 pagine4 SyllogismJan LeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Orthodox Diakonia Worldwide. An Initial PDFDocumento31 pagineOrthodox Diakonia Worldwide. An Initial PDFNalau Sapu RataNessuna valutazione finora

- P. Joseph Cahill-The Theological Significance of Rudolf BultmannDocumento44 pagineP. Joseph Cahill-The Theological Significance of Rudolf BultmannGheorghe Mircea100% (1)

- Community of Service, Love and Fellowship in Johan's GospelDocumento7 pagineCommunity of Service, Love and Fellowship in Johan's Gospeldiamond krishna dasNessuna valutazione finora

- UntitledDocumento10 pagineUntitled1stLadyfreeNessuna valutazione finora

- 2002 - Andries Van Aarde - Methods and Models in The Quest For The Historical JesusDocumento21 pagine2002 - Andries Van Aarde - Methods and Models in The Quest For The Historical Jesusbuster301168Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Portrait of Christ The Hero in The Epistle To The HebrewsDocumento296 pagineA Portrait of Christ The Hero in The Epistle To The HebrewsRasmus TvergaardNessuna valutazione finora

- The Bible and The People of The BookDocumento9 pagineThe Bible and The People of The Bookneferisa100% (1)

- IMC Leeds 2015 Jacques de VitryDocumento1 paginaIMC Leeds 2015 Jacques de VitrymustardandwineNessuna valutazione finora

- Kalamazoo CFP 2015Documento56 pagineKalamazoo CFP 2015mustardandwineNessuna valutazione finora

- Foam RollerDocumento8 pagineFoam RollerSennheiserNessuna valutazione finora

- Nigel Slater Coffee Walnut CakeDocumento5 pagineNigel Slater Coffee Walnut CakemustardandwineNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Cite A Tweet in MLA FormatDocumento1 paginaHow To Cite A Tweet in MLA FormatmustardandwineNessuna valutazione finora

- CF P Obscuritas PragueDocumento1 paginaCF P Obscuritas PraguemustardandwineNessuna valutazione finora

- Chicken Skewers With Grapes RecipeDocumento3 pagineChicken Skewers With Grapes RecipemustardandwineNessuna valutazione finora

- Queens International Conference, Ideal WomanDocumento1 paginaQueens International Conference, Ideal WomanmustardandwineNessuna valutazione finora

- Sensing The Sacred CFPDocumento1 paginaSensing The Sacred CFPmustardandwineNessuna valutazione finora

- CF P Obscuritas PragueDocumento1 paginaCF P Obscuritas PraguemustardandwineNessuna valutazione finora

- Chicken PiccataDocumento2 pagineChicken PiccatamustardandwineNessuna valutazione finora

- Delehaye, Hippolyte. The Work of The Bollandists Through Three Centuries, 1615-1915. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1922.Documento288 pagineDelehaye, Hippolyte. The Work of The Bollandists Through Three Centuries, 1615-1915. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1922.mustardandwine100% (1)

- La Kabylie Et Les Coutumes Kabyles 1/3, Par Hanoteau Et Letourneux, 1893Documento607 pagineLa Kabylie Et Les Coutumes Kabyles 1/3, Par Hanoteau Et Letourneux, 1893Tamkaṛḍit - la Bibliothèque amazighe (berbère) internationale100% (3)

- Shaviro's Reflections On Cinematic BodyDocumento8 pagineShaviro's Reflections On Cinematic BodyAshtray BoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Week07 Affirmations 3 ChannelsDocumento1 paginaWeek07 Affirmations 3 Channelstanaha100% (2)

- The Higher Metaphysics 1000041877Documento68 pagineThe Higher Metaphysics 1000041877sean lee100% (7)

- The Benefits of Reciting The Vajra Guru MantraDocumento8 pagineThe Benefits of Reciting The Vajra Guru MantraMike Dickman100% (1)

- The teachings of Jijuyu-zanmai, the Samadhi of Self-EnjoymentDocumento34 pagineThe teachings of Jijuyu-zanmai, the Samadhi of Self-EnjoymentsengcanNessuna valutazione finora

- Sri Aurobindo's Integral Education PhilosophyDocumento12 pagineSri Aurobindo's Integral Education PhilosophySaroj MeherNessuna valutazione finora

- Rising StrongDocumento3 pagineRising StrongPatricia CoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Nature, The Modern and The Mystic - Tales From Early Twentieth Century GeographyDocumento16 pagineNature, The Modern and The Mystic - Tales From Early Twentieth Century Geographydhruba.sarkar3695Nessuna valutazione finora

- Daily PrayersDocumento74 pagineDaily Prayersrickyreema67% (3)

- JIGME PHUNTSOK, Vajrasattva PracticeDocumento3 pagineJIGME PHUNTSOK, Vajrasattva Practicemvanth100% (1)

- Vipassana Meditation Guidelines by Chanmyay SayadawDocumento12 pagineVipassana Meditation Guidelines by Chanmyay SayadawTeguh KiyatnoNessuna valutazione finora

- Troma Nagmo (Krodikali)Documento240 pagineTroma Nagmo (Krodikali)John Root100% (6)

- Watch TowerDocumento3 pagineWatch TowerivahdamNessuna valutazione finora

- E-Learning Pathmaps - HTMDocumento3 pagineE-Learning Pathmaps - HTMRLeite RlNessuna valutazione finora

- Spiritual Laws That Govern Humanity and The Universe - Lonnie EdwardsDocumento108 pagineSpiritual Laws That Govern Humanity and The Universe - Lonnie EdwardsMagicien1100% (2)

- 07 Chapter 3Documento71 pagine07 Chapter 3rahulkn2009Nessuna valutazione finora

- v21 2Documento44 paginev21 2Jasbeer MusthafaNessuna valutazione finora

- SoulMate BookDocumento218 pagineSoulMate BookAnoo P100% (8)

- Gandharva TantraDocumento23 pagineGandharva TantraShanthi GowthamNessuna valutazione finora

- Tantra Jyoti SH Camp ReportDocumento36 pagineTantra Jyoti SH Camp ReportVimalMalviyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sources of StrengthDocumento26 pagineSources of StrengthMYRA R. SABEROLANessuna valutazione finora

- Faizan e DarweshDocumento130 pagineFaizan e DarweshFarooq HussainNessuna valutazione finora

- Prior To ConsciousnessDocumento162 paginePrior To ConsciousnessSmith KolemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ten Maxims English - V3 PDFDocumento65 pagineTen Maxims English - V3 PDFSIVAKUMARNessuna valutazione finora

- Ibn Khaldun's Critics of SufismDocumento57 pagineIbn Khaldun's Critics of SufismAbidin ZeinNessuna valutazione finora

- Berlage Hendrik Petrus Thoughts On Style 1886-1909Documento350 pagineBerlage Hendrik Petrus Thoughts On Style 1886-1909ELA TJNessuna valutazione finora

- Daily Practice DownloadDocumento5 pagineDaily Practice DownloadDana MesseguerNessuna valutazione finora

- Sacred Hoop 42Documento48 pagineSacred Hoop 42Jacques Fourcade100% (3)

- Wei Wu Wei (Terrence Gray) - The Effortless WayDocumento17 pagineWei Wu Wei (Terrence Gray) - The Effortless Wayapi-370216767% (12)

- 2005 Karel Werner - A Popular Dictionary of Hinduism (RevED)Documento129 pagine2005 Karel Werner - A Popular Dictionary of Hinduism (RevED)qutobolNessuna valutazione finora

- Lakshmi StotrasDocumento4 pagineLakshmi Stotrassameer1973Nessuna valutazione finora

- Out of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyDa EverandOut of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (10)

- The Dangers of a Shallow Faith: Awakening From Spiritual LethargyDa EverandThe Dangers of a Shallow Faith: Awakening From Spiritual LethargyValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (134)

- Now and Not Yet: Pressing in When You’re Waiting, Wanting, and Restless for MoreDa EverandNow and Not Yet: Pressing in When You’re Waiting, Wanting, and Restless for MoreValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (4)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsDa EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNessuna valutazione finora

- Bait of Satan: Living Free from the Deadly Trap of OffenseDa EverandBait of Satan: Living Free from the Deadly Trap of OffenseValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (308)

- Out of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyDa EverandOut of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (5)

- Crazy Love, Revised and Updated: Overwhelmed by a Relentless GodDa EverandCrazy Love, Revised and Updated: Overwhelmed by a Relentless GodValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (1000)

- The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness: The Path to True Christian JoyDa EverandThe Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness: The Path to True Christian JoyValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (188)

- Tired of Being Tired: Receive God's Realistic Rest for Your Soul-Deep ExhaustionDa EverandTired of Being Tired: Receive God's Realistic Rest for Your Soul-Deep ExhaustionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Just Do Something: A Liberating Approach to Finding God's WillDa EverandJust Do Something: A Liberating Approach to Finding God's WillValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (95)

- How to Walk into a Room: The Art of Knowing When to Stay and When to Walk AwayDa EverandHow to Walk into a Room: The Art of Knowing When to Stay and When to Walk AwayValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (4)

- The Blood of the Lamb: The Conquering WeaponDa EverandThe Blood of the Lamb: The Conquering WeaponValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (234)

- The Deconstruction of Christianity: What It Is, Why It’s Destructive, and How to RespondDa EverandThe Deconstruction of Christianity: What It Is, Why It’s Destructive, and How to RespondValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (26)

- The False White Gospel: Rejecting Christian Nationalism, Reclaiming True Faith, and Refounding DemocracyDa EverandThe False White Gospel: Rejecting Christian Nationalism, Reclaiming True Faith, and Refounding DemocracyValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (2)

- Holy Hygge: Creating a Place for People to Gather and the Gospel to GrowDa EverandHoly Hygge: Creating a Place for People to Gather and the Gospel to GrowValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (100)

- What's Best Next: How the Gospel Transforms the Way You Get Things DoneDa EverandWhat's Best Next: How the Gospel Transforms the Way You Get Things DoneValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (33)

- The Well-Watered Woman: Rooted in Truth, Growing in Grace, Flourishing in FaithDa EverandThe Well-Watered Woman: Rooted in Truth, Growing in Grace, Flourishing in FaithValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (63)

- Jesus and the Powers: Christian Political Witness in an Age of Totalitarian Terror and Dysfunctional DemocraciesDa EverandJesus and the Powers: Christian Political Witness in an Age of Totalitarian Terror and Dysfunctional DemocraciesValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (5)

- For Women Only, Revised and Updated Edition: What You Need to Know About the Inner Lives of MenDa EverandFor Women Only, Revised and Updated Edition: What You Need to Know About the Inner Lives of MenValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (267)

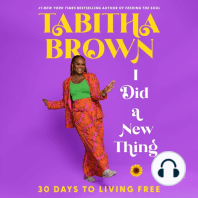

- I Did a New Thing: 30 Days to Living FreeDa EverandI Did a New Thing: 30 Days to Living FreeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (17)