Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Fuchs - There Are No Palestinian Refugees

Caricato da

AviDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Fuchs - There Are No Palestinian Refugees

Caricato da

AviCopyright:

Formati disponibili

There Are No Palestinian Refugees

Concerning the Arab Claim of the Right of Return

Yossi Fuchs, Adv.*

*The writer is an attorney, a graduate of Bar Ilan University Law School and a founding member of the Legal Forum for Israel. He specializes in Administrative Law, Constitutional Law and International Law.

One of Israels major problems in international relations concerns its response to the ongoing process of politization of international law concerning the Arab-Israeli conflict.

This process is expressed in several respects, of which the most common is adoption of the term occupation when referring to the territories obtained by Israel as a result of the Six-Day War a war instigated by the Arab states that led to the redemption of Judea and Samaria from Jordanian occupation and the Gaza Strip from Egyptian occupation. Generally, international bodies consider Israel to be an occupying country in these areas1 according to the Fourth Geneva Convention.2 The Arab world, United Nations agencies and many countries completely overlook the designation of these areas as part of the Jewish homeland to be established in what was historically Eretz Israel. They ignore the recognition and unanimous approval of this legal right by the League of Nations Council in 1922.3 It was subsequently included in Article 80 of the United Nations Charter4 and remains valid to this day. Prof. Eugene Rostow, former Dean of Yale University Law School and the US Undersecretary of State who worded UN Resolution 242,5 stated that the Jews have the right to settle in Judea and Samaria just as they have the right to settle in Haifa, Tel Aviv or Jerusalem.6

S Resolution 446 of 22 March 1979; S Resolution 465 (1980) of 3 March 1980 Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 3 C.529.M.314.1922.VI, Mandate for Palestine League of Nations 4 Charter of the United Nations, Chapter XII International Trusteeship System, Article 80 5 S. C. Res. 242, U.N. SCOR, 22nd Sess., U.N. Doc. S/RES/242 (1967) 6 Rostow, Eugene V., The New Republic, 23 April1990: The Historical Approach to the Issue of the Legality of Jewish Settlement Activity.

2

-2-

Another example of this process is the definition of the Arab population as Palestinians, while all relevant international resolutions referred to the Land of Israel as Palestine7 and to its inhabitants according to their nationality: Jews or Arabs. For example, the League of Nations resolution clearly indicates:

recognition has thereby been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country8

UN General Assembly Resolution 181 of November 29, 1947, a resolution rejected immediately by the Arab states, also refers clearly to the division of Palestine and the establishment of a Jewish State and an Arab State.9 The term Palestinian State was not mentioned. Only in later years, especially after the Six-Day War, did the Arab states adopt the term Palestinians, as if they had been born and raised in a country called Palestine for many generations, as if they were the descendants of the ancient Philistines and are now attempting to gain release from the Israeli occupation of their land and rebuild a Palestinian state a state that never existed historically.

One does not have to be a historian or a lawyer to understand that the Palestinians are an integral part of the Arab nation.10 There is no Palestinian language, no historical basis for the existence of a Palestinian people and no legal rights particular to such a group.

Uriel Dan and Yaacov Shimoni (Hebrew), Arab-Palestinian Society and the Transjordan Emirate, The State and the National Home (1917-1947) (in: Yehoshua Porat & Yaacov Shavit (editors), 9th Vol., Yad Ben-Zvi/Keter 1982), P. 263. Additional Examples: The Balfour Declaration 1917; British White Paper of June 1922; British White Paper of 1939; also see http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/mideast.asp. 8 See footnote 3. 9 Resolution 181 (II). Future government of Palestine, A/RES/181(II), 29 November 1947 10 GA Ord Res, 2nd Session, 1947, Ad hoc Committee on the Palestine Question, pp.5-11, also in: Lapidoth and Hirsch (eds.), The Jerusalem Question and its Resolution: Selected Documents (Dordrecht 1994), 13.

-3The most extreme example of the politization of international law is the Palestinian demand of the right of return. To understand this demand, we must first examine the question of whether the Palestinian refugees really exist at all.

It is a historical fact that during the Israeli War of Independence (1947-1949), between 500,000 and 750,000 Arab residents of the Jewish State11 left their homes and settled in nearby countries, in the hope that the newborn State of Israel would be quickly destroyed by an onslaught of numerous Arab states, a victory that would lead to their speedy and triumphant return. They were housed in refugee camps built for them in the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip and in the Jordanian-occupied areas of Judea and Samaria, as well as in Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

Recognition of the people as refugees

The only definition of refugee recognized in International Law is spelled out by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees12 in the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees13 signed in Geneva on July 28, 1951. A refugee is defined as a person who:

As a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to wellfounded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.14

The same Convention denies refugee status to any person who was given citizenship in the absorbing country or who was offered citizenship but refused,15 to ensure that

11 12

Arlene Kushner, The UN Refugee Problem (Hebrew), Techelet 23, Spring 2006, 2 UNHCR United Nations High Commission for Refugees 13 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees 1951 14 Chapter I: General Provisions, Article 1, definition of the term refugee, A(2)

-4the term refugee would not be used for political purposes. According to this definition, a refugee can never pass on his status to his descendants. On the contrary: A descendant of a refugee who was born in a different country is eligible to receive citizenship of that country by birth.

At this point, we should mention another historical fact: After the State of Israel was established, about 900,000 Jews16 were forced to flee their homes in Arab countries due to widespread persecution. Most of them arrived in Israel. In spite of the severe economic difficulties entailed in the absorption of such vast numbers of people, all were granted Israeli citizenship and were therefore not considered refugees by the international standards stated above.

Among the Arabs who fled, many lived in Palestine only for a few years before fleeing, having arrived not long before the War of Independence in search of work.17 It would be difficult to consider them permanent residents before they fled. Large numbers of refugees accepted Jordanian citizenship. Others were eligible for it but refused.

Application of the legal definition of refugee to the Arabs who fled during the Israeli War of Independence thus leads to the conclusion that today, 65 years later, very few, if any, can be considered refugees. As for those few who do qualify, international law does not accord them the right to return to their former country, if such a country exists. This issue will be examined in greater detail below.

The problem is that the Arab countries insisted on including an additional clause in the Convention,18 whereby any person who received aid from UNRWA or other UN agencies (as in the case of the Palestinian refugees) will not be under the authority of the UN High Commissioner of Refugees. This provision was added because the Arab

15 16

Chapter I: General Provisions, Article 1, definition of the term refugee, C(1) Itamar Levin, Downfall in the East: The Liquidation of the Jewish Communities in Arab Countries and the Robbery of their Property (Hebrew) (Ministry of Defence Publishing House, 2001); Dershowitz, Case for Israel, 42-43, 88-89; Michael Oren, Six Days of War, June 1967, The Making of the Modern Middle East (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002), 3-4, 307-308. 17 Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Problem, 1947-1949. 18 Chapter I: General Provisions, Article 1, definition of the term refugee, D(1) .

-5countries feared that the non-political character of the work envisaged for the nascent UNHCR was not compatible with the highly politicized nature of the Palestinian question.19

Our conclusion is that the Arab states declared that even if the Arabs who fled are not recognized as refugees by international law, they will receive political recognition as Palestinian refugees.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) was established by General Assembly Resolution 338 of December 8, 1949 as an autonomous body whose purpose is to supply relief and work to the Palestinian refugees20 who fled Israel during the War of Independence. Dealing with the return of the refugees was never its function, however. UNRWA was founded before the establishment of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. As the UN General Assembly did not define who is to be considered a Palestinian refugee eligible for UN aid, UNRWA drafted its own definition of refugee:

People whose regular domicile was Palestine between June 1946 and May 1948 and who lost their homes and sources of income as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

This definition proves that UNRWA was well aware of the universal definition of refugees, that includes only persons who were permanent residents of one country before leaving that country. UNRWA was compelled to redefine the term refugee to include all the Arabs who fled, including those who immigrated to Palestine shortly before the war for purposes of finding work and later lost their source of income.

At that time, UNRWA had not yet initiated its successful plan to bequeath refugee status to the descendants of the 1948 refugees. This initiative came about much later, with the emergence of the second generation of refugees, its purpose being to perpetuate the status of Palestinian refugees among future generations.

19

UNHCR, The State of the Worlds Refugees: Fifty Years of Humanitarian Action (Oxford, 2004), Chapter 1, The Early Years, Box 1.2. 20 A/RES/302 (IV) 8 December 1949, Assistance to Palestine Refugees.

-6-

A comparison of statistics on refugees throughout the world, published by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees the UN agency that helps rehabilitate uprooted refugees everywhere shows that the number of refugees is constantly declining, while the number of Palestinian refugees under UNRWA supervision is constantly rising, with no rehabilitation in sight. On the contrary: the aim is to perpetuate refugee status. UNRWA states21 that its present purpose is to supply education, health services and relief to eligible refugees from among the 4.6 million Palestinian refugees who live in five areas of activity: Jordan, Lebanon, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank and Syria.

We should note that UNRWAs misdeeds include not only perpetuation of refugee status, that utterly contradicts the humanitarian purpose for which it was established, but also support of educational facilities for tens of thousands of children that attempt to teach them a deep hatred for Israel, while inculcating the idea of the future return of millions of Arabs to Israel and legitimizing acts of terror against Israeli citizens.22

Relevant UN Resolutions

The Arab world generally presents General Assembly Resolution 194 (III) of December 11, 194823 as evidence of the right of return for Palestinian refugees. Nothing is farther from the truth, however. General Assembly resolutions, as opposed to Security Council resolutions, are not binding. They are declarative

recommendations that depend entirely on the mutual agreement of the relevant parties.24

UNRWA website : http://www.unrwa.org. Emanuel Marx and Nitza Nachmias, Dilemmas of Prolonged Humanitarian Aid Operations: The Case of UNHCR, The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, June 22, 2004; Hamas Scores Sweeping Victory in UNRWA Elections, Palestine Information Center, June 10, 2003; www.palestineinfo.co.uk/am/publish/article_1214.shtml; Allison Kaplan Sommer, UNRWA on Trial, Reform Judaism (Winter 2002), p.42; Report (Hebrew) of November 2003 concerning investigations of UNRWA actions. See: www.gao.gov/new.items/d04276r.pdf 23 A/RES/194 (III). Palestine Progress Report of the United Nations Mediator, 11 December 1948 24 Brownlie 1990, 14, 699; Shaw 1997, 89; Akehurst 1997, 378.

22

21

-7Resolution 194 deals with several issues, including an attempt to bring about a ceasefire agreement between the parties to the conflict, the establishment of a reconciliation committee, the demilitarization of Jerusalem, protection of the holy places and the refugee issue (Clause 11).25 This clause does not mention Arab or Palestinian refugees specifically but rather addresses the general issue of refugees, meaning Jewish as well as Arab refugees. It states that refugees should be permitted to return to their homes. The emphasis is on loss of property not loss of a homeland. Moreover, the term should is a term designating a recommendation rather than a binding or compulsory statement. No mention is made of such a legal inherent right. The recommendation is only applicable on condition that the parties are willing to live in full peace with their neighbors at the earliest possible practicable point in time. Furthermore, the resolution stated that refugees who elect not to return to their former homes will be eligible for restitution payments to be tendered by the responsible governments and/or authorities. No mention is made of the Government of Israel as the responsible authority in this matter. As such, it is clear that ultimate responsibility for the Arab refugee problem (and the problem of Jewish refugees who fled Arab countries) lies with the Arab states who chose to launch an all-out attack on the fledgling Jewish state just hours after its birth and not with the state that was the victim of that attack. In any case, the value of the property that the Jewish refugees fleeing Arab countries left behind is far greater than that of the property left behind by the Arab refugees.26

It should also be noted that many Arab states, including Egypt, Lebanon and Syria, voted against Resolution 194, just as they voted against the one calling for partition Resolution 181 (at that time, all Arab countries voted against it). This does not prevent the Palestinians from raising the baseless issue of the so-called right of return, even after their representatives voted against it and viewed the resolutions as non-binding.

A/RES/194 (III), 11: Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date 26 Yaffa Zilbershatz & Nimera Goren-Amitai, The Return of the Palestinian Refugees to the State of Israel, edited by Ruth Gabizon. The Mazila Center for Zionist, Jewish, Liberal and Humanitarian Issues, Jerusalem, 2010, p. 38.

25

-8An additional resolution (Resolution 393 (V)) was accepted by the General Assembly on December 2, 1950 and was defined as Aid to the Refugees from Palestine. The resolution states:

The General Assembly considers that, without prejudice to the provisions of Paragraph 11 of General Assembly Resolution 194 (III) of 11 December 1948, the reintegration of the refugees into the economic life of the Near East, either by repatriation or resettlement, is essential in preparation for the time when international assistance is no longer available, and for the realization of conditions of peace and stability in the area27

This resolution supports our interpretation of Resolution 194, that resettlement of Arab refugees in Arab countries was a distinct option at the time that the resolution was adopted. Security Council Resolution 242,28 adopted after the Six-Day War, referred to the refugee problem, declaring that it should have a just solution. The same wording was used subsequently in Resolution 338. It is no coincidence that term Palestinian refugees was not used. No one was granted a legal right of return. The basis of this resolution was recognition that each side to the conflict has refugees, as detailed above. As such, when discussing an agreement to end the conflict permanently, one cannot ignore the refugee problem. Just as the Jewish refugees who fled from Arab countries were absorbed in the State of Israel and became Israeli citizens, so should the Arab states act in the same manner towards the Arab refugees.

Increased politization of the UN General Assembly became an established fact. Following the Six-Day War of June 1967 and even more so after the Yom Kippur War of October 1973, the Assembly adopted resolutions that recognized the Palestinian People and its right to political independence. The Assembly also referred to the Palestinians right of return to their homes (deleting the term refugees).

27 28

A/RES/393 (V), 2 December 1950, Assistance to Palestinian Refugees. S.C. Res. 242, U.N. SCOR, 22nd Sess., U.N. Doc. S/RES/242 (1967).

-9General Assembly Resolution 3236 of November 22, 1974 stated in Clause 2 that the General Assembly:

Reaffirms also the inalienable right of the Palestinians to return to their homes and property from which they have been displaced and uprooted, and calls for their return.29

It should be noted that this resolution (similar to Resolution 194) concerns returning to homes and property (and not to their country). Such property did not even exist at the time the decision was adopted. If Arab refugees were to submit legal monetary claims for the loss of property, these would be set off by similar counterclaims of Jewish refugees from Arab countries, with a huge surplus in favor of the latter.

In later years, the General Assembly repeatedly accepted resolutions referring to Palestinian rights, while omitting any reference to refugees, apparently because limiting the rights to refugees (as universally defined and as contrasted with the UNRWA definition) would mean that there are no longer refugees who could benefit from the rights.

The politization of General Assembly resolutions reached a peak with Resolution 3379 of November 10, 1975, stating that Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination.30

May we point out that International Law does not recognize a right of return of any other group of refugees to return to the countries from which they fled and does not require any country to reaccept such refugees.31 In fact, modern history includes many conflicts that led to the exchange of civilian populations and the resettlement of refugees in their new countries.

A/RES/3236 (XXIX), Question of Palestine, 22 November 1974. A/RES/3379 (XXX), Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. 31 Yaffa Zilbershatz & Nimera Goren-Amitai, The Return of the Palestinian Refugees to the State of Israel, edited by Ruth Gabizon. The Mazila Center for Zionist, Jewish, Liberal and Humanitarian Issues, Jerusalem, 2010, Third Chapter, p.65.

30

29

- 10 Conclusions According to the universally accepted definition of refugee as implemented in the Israeli War of Independence, a person whose domicile was in Palestine (barring persons who immigrated to Palestine shortly before the War in search of work) and who has not been offered citizenship from his country of refuge is indeed a refugee.

How many people are there to whom the above definitions can be applied? Very few and possibly none at all.

Does international law recognize a right of return of these few refugees to Israel? No.

Therefore: Instead of opposing the claims of the Arab so-called right of return for demographic reasons, such as the potential loss of the Jewish majority in the State of Israel, we must simply tell the truth: There are no Palestinian refugees!

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Temple Mount by Rabbi Mordechai RabinovitchDocumento5 pagineTemple Mount by Rabbi Mordechai RabinovitchAvi100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- הלכות עליה להר הביתDocumento3 pagineהלכות עליה להר הביתAviNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Chanukah Map in English!Documento1 paginaThe Chanukah Map in English!Avi100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Chizuk Now BrochureDocumento2 pagineChizuk Now BrochureAviNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Israeli Documentary Remembers Jerusalem Saint - ArticleDocumento3 pagineIsraeli Documentary Remembers Jerusalem Saint - ArticleAviNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- List of Projects For CommunitiesDocumento10 pagineList of Projects For CommunitiesAviNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

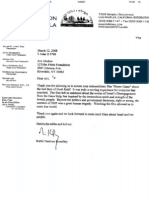

- One of The Lamed Vav - Reb Aryeh Levin Beit Shemesh Recommendation LetterDocumento1 paginaOne of The Lamed Vav - Reb Aryeh Levin Beit Shemesh Recommendation LetterAviNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Programs For Educational ProgramsDocumento1 paginaPrograms For Educational ProgramsAviNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- One of The 36 - Screening Flyer/PosterDocumento1 paginaOne of The 36 - Screening Flyer/PosterAviNessuna valutazione finora

- Home Game Movie Recommendation LetterDocumento1 paginaHome Game Movie Recommendation LetterAviNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- List of Projects For Educational Inst.Documento10 pagineList of Projects For Educational Inst.AviNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Programs For Educational ProgramsDocumento1 paginaPrograms For Educational ProgramsAviNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- An ATFP Presentation: The American Task Force On PalestineDocumento42 pagineAn ATFP Presentation: The American Task Force On PalestineNitin Mann100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The New Zionist Rampage in GazaDocumento4 pagineThe New Zionist Rampage in GazaMichael TheodoreNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- 2 Hunger StrikeDocumento2 pagine2 Hunger StrikekwintencirkelNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing One State and Two State Proposals To Solve The Israel Palestine ConflictDocumento7 pagineAssessing One State and Two State Proposals To Solve The Israel Palestine Conflictvan zonnenNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Hamas Contained The Riseand Pacificationof Palestinian Resistance 1Documento5 pagineHamas Contained The Riseand Pacificationof Palestinian Resistance 1sabra muneerNessuna valutazione finora

- Hilma GranqvistDocumento1 paginaHilma GranqvistburnnotetestNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Leila KhalidDocumento1 paginaLeila KhalidSeema SindhuNessuna valutazione finora

- Ghaza Strip - HistoryDocumento5 pagineGhaza Strip - HistoryCristian Popescu100% (1)

- Slingshot Israel Poll 10.31.23Documento4 pagineSlingshot Israel Poll 10.31.23evanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Revisionism On The West BankDocumento8 pagineRevisionism On The West BankHoang Thanh TungNessuna valutazione finora

- Palestinian Civil Society: A Time For Action by Amal AbusrourDocumento11 paginePalestinian Civil Society: A Time For Action by Amal AbusrourAlex MatineNessuna valutazione finora

- Gaza Is The Scandal The World ForgotDocumento3 pagineGaza Is The Scandal The World ForgotAjit NairNessuna valutazione finora

- Palestine RecogmitonDocumento48 paginePalestine RecogmitonSaurav Kumar100% (1)

- Camp - David. .The - Tragedy.of - ErrorsDocumento14 pagineCamp - David. .The - Tragedy.of - ErrorsajbajbajbNessuna valutazione finora

- Initial Findings of The Profile of Palestinian Terrorists Who Carried Out Attacks in Israel in The Current Wave of TerrorismDocumento66 pagineInitial Findings of The Profile of Palestinian Terrorists Who Carried Out Attacks in Israel in The Current Wave of TerrorismloreNessuna valutazione finora

- BBA LLB Div A Project Topics PIL - 2021-2022 JulyDocumento6 pagineBBA LLB Div A Project Topics PIL - 2021-2022 Julyzuhaib habibNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- City Council Gaza ResolutionDocumento4 pagineCity Council Gaza ResolutionIndiana Public Media NewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Dissertation Topics On PalestineDocumento7 pagineDissertation Topics On PalestineHowToFindSomeoneToWriteMyPaperUK100% (1)

- Curriculum VitaeDocumento2 pagineCurriculum VitaeRana KhaledNessuna valutazione finora

- Guyana and The Islamic WorldDocumento21 pagineGuyana and The Islamic WorldshuaibahmadkhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Munir Akram ArticlesDocumento24 pagineMunir Akram ArticlesSaqlainNessuna valutazione finora

- Seas and Bordering CountriesDocumento17 pagineSeas and Bordering Countriesarshmanever143Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Palestinian Peace Dividend - Jerry NocklesDocumento3 pagineA Palestinian Peace Dividend - Jerry NocklesJerry NocklesNessuna valutazione finora

- 2008-02-01 - Egypt-Gaza Border Effect On Israeli-Egyptian Relations 101806 PDFDocumento5 pagine2008-02-01 - Egypt-Gaza Border Effect On Israeli-Egyptian Relations 101806 PDFapi-26004521Nessuna valutazione finora

- Listen To The Following Passage, Then Answer The Questions BelowDocumento2 pagineListen To The Following Passage, Then Answer The Questions BelowmmmNessuna valutazione finora

- Operation Al-Aqsa Storm Friday Talking PointsDocumento2 pagineOperation Al-Aqsa Storm Friday Talking PointsSuhaib Patel100% (1)

- An Introduction To PalestineDocumento61 pagineAn Introduction To PalestineSJP at UCLA67% (3)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- ANERA Honors Qatar KuwaitDocumento2 pagineANERA Honors Qatar KuwaitInterActionNessuna valutazione finora

- Draft ResolutionDocumento6 pagineDraft ResolutionBrahmjotNessuna valutazione finora

- Hamas: A Beginner's Guide: Khaled Hroub London and Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto Press, 2006Documento4 pagineHamas: A Beginner's Guide: Khaled Hroub London and Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto Press, 2006Salim UllahNessuna valutazione finora