Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Mezirow Transformative Learning

Caricato da

visual18Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Mezirow Transformative Learning

Caricato da

visual18Copyright:

Formati disponibili

This chapter summarizes the transformation theory of adult learning, explains the relationship of transformative learning to autonomous, responsible

thinking (viewed as the central goal of adult education), and discusses practical implications for educators.

Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice

Jack Mezirow

A defining condition of being human is that we have to understand the meaning of our experience. For some, any uncritically assimilated explanation by an authority figure will suffice. But in contemporary societies we must learn to make our own interpretations rather than act on the purposes, beliefs, judgments, and feelings of others. Facilitating such understanding is the cardinal goal of adult education. Transformative learning develops autonomous thinking.

Transformative Learning Theory

Transformative learning (Mezirow, 1991, 1995, 1996; Cranton, 1994, 1996) is the process of effecting change in a frame of reference. Adults have acquired a coherent body of experienceassociations, concepts, values, feelings, conditioned responsesframes of reference that define their life world. Frames of reference are the structures of assumptions through which we understand our experiences. They selectively shape and delimit expectations, perceptions, cognition, and feelings. They set our line of action. Once set, we automatically move from one specific activity (mental or behavioral) to another. We have a strong tendency to reject ideas that fail to fit our preconceptions, labeling those ideas as unworthy of considerationaberrations, nonsense, irrelevant, weird, or mistaken. When circumstances permit, transformative learners move toward a frame of reference that is more inclusive, discriminating, self-reflective, and integrative of experience. A frame of reference encompasses cognitive, conative, and emotional components, and is composed of two dimensions: habits of mind and a point of view. Habits of mind are broad, abstract, orienting, habitual ways of thinking, feeling,

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR ADULT AND CONTINUING EDUCATION, no. 74, Summer 1997 Jossey-Bass Publishers

TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING IN ACTION

and acting influenced by assumptions that constitute a set of codes. These codes may be cultural, social, educational, economic, political, or psychological. Habits of mind become articulated in a specific point of viewthe constellation of belief, value judgment, attitude, and feeling that shapes a particular interpretation. An example of a habit of mind is ethnocentrism, the predisposition to regard others outside ones own group as inferior. A resulting point of view is the complex of feelings, beliefs, judgments, and attitudes we have regarding specific individuals or groups (for example, homosexuals, welfare recipients, people of color, or women). Frames of reference are primarily the result of cultural assimilation and the idiosyncratic influences of primary caregivers. Habits of mind are more durable than points of view. Points of view are subject to continuing change as we reflect on either the content or process by which we solve problems and identify the need to modify assumptions. This happens whenever we try to understand actions that do not work the way we anticipated. We can try out another persons point of view and appropriate it, but we cannot do this with a habit of mind. Points of view are more accessible to awareness and to feedback from others. Jrgen Habermas (1981) has helped us to understand that problem solving and learning may be instrumentallearning to manipulate or control the environment or other people to enhance efficacy in improving performance; impressionisticlearning to enhance ones impression on others, to present oneself; normativelearning oriented to common values and a normative sense of entitlement (members of the group are entitled to expect certain behavior); or communicativelearning to understand the meaning of what is being communicated. Communicative learning involves at least two persons striving to reach an understanding of the meaning of an interpretation or the justification for a belief. Ideally, communicative learning involves reaching a consensus. In instrumental learning, the truth of an assertion may be established through empirical testing. But communicative learning involves understanding purposes, values, beliefs, and feelings and is less amenable to empirical tests. In communicative learning, it becomes essential for learners to become critically reflective of the assumptions underlying intentions, values, beliefs, and feelings. If someone claims he loves you, how authentic is the expression of affection? Is the intent of a friendly stranger to sell you something, to proselytize, or make a sexual overture? Is an acquaintance being truthful? Is what is communicated only a rationalization? Is it meant to be taken literally or as a metaphor? Is the message of a play what you interpret it to be? To resolve these questions of assumption, we rely on a tentative best judgment among those whom we believe to be informed, rational, and objective. We engage in discourse to validate what is being communicated. Our only other recourse is to turn to an authority or tradition to make a judgment for us. Discourse, as used here, is a dialogue devoted to assessing reasons presented in support of competing interpretations, by critically examining evidence, arguments, and alternative points of view. The more interpretations of

TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING: THEORY TO PRACTICE

a belief available, the greater the likelihood of finding a more dependable interpretation or synthesis. We learn together by analyzing the related experiences of others to arrive at a common understanding that holds until new evidence or arguments present themselves. We transform our frames of reference through critical reflection on the assumptions upon which our interpretations, beliefs, and habits of mind or points of view are based. We can become critically reflective of the assumptions we or others make when we learn to solve problems instrumentally or when we are involved in communicative learning. We may be critically reflective of assumptions when reading a book, hearing a point of view, engaging in task-oriented problem solving (objective reframing), or self-reflectively assessing our own ideas and beliefs (subjective reframing). Self-reflection can lead to significant personal transformations. Critically explored assumptions may be in the autobiographical context of a belief, or they may be supporting a social, cultural, economic, political, educational, or psychological system. Transformations in frames of reference take place through critical reflection and transformation of a habit of mind, or they may result from an accretion of transformations in points of view. There are four processes of learning. Referring to the ethnocentric example, one process is to elaborate an existing point of viewwe can seek further evidence to support our initial bias regarding a group and expand the range or intensity of our point of view. A second way we learn is to establish new points of view. We can encounter a new group and create new negative meaning schemes for them by focusing on their perceived shortcomings, as dictated by our propensity for ethnocentricity. A third way we learn is to transform our point of view. We can have an experience in another culture that results in our critically reflecting on our misconceptions of this particular group. The result may be a change in point of view toward the group involved. As a result, we may become more tolerant or more accepting of members of that group. If this happens over and over again with a number of different groups, it can lead to a transformation by accretion in our governing habit of mind. Finally, we may transform our ethnocentric habit of mind by becoming aware and critically reflective of our generalized bias in the way we view groups other than our own. Such epochal transformations are less common and more difficult. We do not make transformative changes in the way we learn as long as what we learn fits comfortably in our existing frames of reference.

Autonomous Thinking

Thinking as an autonomous and responsible agent is essential for full citizenship in democracy and for moral decision making in situations of rapid change. The identified learning needs of the workforce implicitly recognize the centrality of autonomous learning.

TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING IN ACTION

The U.S. Department of Labors SCANS report (1991) identifies acquiring and using information, identifying and organizing resources, working with others, interpreting information, and understanding complex interrelationships as essential competencies and skills. Similarly, the key competencies for workforce preparation identified by the Australian government, employers, and academics include analyzing information, communicating ideas, planning and organizing activities, using mathematical ideas and technology, working in teams, solving problems, and using cultural understandings (Gonzi and others, 1995). The common presumption in these lists is that the essential learning required to prepare a productive and responsible worker for the twenty-first century must empower the individual to think as an autonomous agent in a collaborative context rather than to uncritically act on the received ideas and judgments of others. Workers will have to become autonomous, socially responsible thinkers. As we move into the next century and more technologically sophisticated industry and service sectors, work becomes more abstract, depending on understanding and manipulating information rather than merely acquiring it. New forms of skill and knowledge are required. There is a growing consensus pertaining to the essential understandings, skills, and dispositions required for an adult learner to become an effective member of the workforce of the future. Economists recognize that resources should be directed toward creating a workforce that can adapt to changing conditions of employment, exercise critical judgement as it manages technology systems, and flexibly engage in more effective collaborative decision making. Adult learners themselves view learning to think as autonomous, responsible persons as an important educational objective. For example, the U.S. National Institute for Literacy (Stein, 1995) found that those who participate in literacy programs do so to (1) gain access to information so they can orient themselves in the world; (2) give voice to their ideas, with the confidence they will be heard; (3) make decisions and act independently; and (4) build a bridge to the future by learning how to learn. Their goal is to become autonomous, responsible thinkers. Often, adult learners immediate focus is on practical, short-term objectivesto be able to qualify for a drivers license, get a job or promotion, or teach a child to read. It is crucial to recognize that learning needs must be defined so as to recognize both short-term objectives and long-term goals. The learners immediate objectives may be described in terms of subject matter mastery, attainment of specific competencies, or other job-related objectives, but his or her goal is to become a socially responsible autonomous thinker. The adult educator must recognize both the learners objectives and goal. The educators responsibility is to help learners reach their objectives in such a way that they will function as more autonomous, socially responsible thinkers. Helping people learn to achieve a specific short-term objective may involve instrumental learning. For them to achieve their goal requires communicative learning.

TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING: THEORY TO PRACTICE

Autonomy here refers to the understanding, skills, and disposition necessary to become critically reflective of ones own assumptions and to engage effectively in discourse to validate ones beliefs through the experiences of others who share universal values. Transformation theory holds that moral values are legitimized by agreement through discourse. The universality of such values as truth, justice, and freedom is based on the claim that they have been found to result in more beneficial action than their alternatives. The Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations attests to this. The claim is that if everyone could participate in a discourse, under the ideal conditions of discourse, there would be a universal rational consensus concerning these values. There is an egregious assumption that the acquisition of knowledge or attainment of competencies will somehow automatically generate the understandings, skills, and dispositions involved in learning to think autonomously. However, there are different processes of learning involved and different forms of appropriate educational intervention.

Foundations

Children commonly acquire a foundation of the specific learning required to think autonomously. This includes the ability and disposition to (1) recognize cause-effect relationships, (2) use informal logic in making analogies and generalizations, (3) become aware of and control their own emotions, (4) become empathic of others, (5) use imagination to construct narratives, and (6) think abstractly. Adolescents may learn to (7) think hypothetically, and (8) become critically reflective of what they read, see, and hear. In adulthood, the task is to strengthen and build on this foundation in order to assist the learner to understand new subject content, but, in the process of doing so, to become (1) more aware and critical in assessing assumptionsboth those of others and those governing ones own beliefs, values, judgments, and feelings; (2) more aware of and better able to recognize frames of reference and paradigms (collective frames of reference) and to imagine alternatives; and (3) more responsible and effective at working with others to collectively assess reasons, pose and solve problems, and arrive at a tentative best judgment regarding contested beliefs. Becoming critically reflective of the assumptions of others is fundamental to effective collaborative problem posing and solving. Becoming critically reflective of ones own assumptions is the key to transforming ones taken-forgranted frame of reference, an indispensable dimension of learning for adapting to change.

Education for Transformative Learning

Adult educators need to understand that transformative learning can take several forms involving either objective or subjective reframing. Transformative learning

10

TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING IN ACTION

is rooted in the way human beings communicate and is a common learning experience not exclusively concerned with significant personal transformations. To facilitate transformative learning, educators must help learners become aware and critical of their own and others assumptions. Learners need practice in recognizing frames of reference and using their imaginations to redefine problems from a different perspective. Finally, learners need to be assisted to participate effectively in discourse. Discourse is necessary to validate what and how one understands, or to arrive at a best judgment regarding a belief. In this sense, learning is a social process, and discourse becomes central to making meaning. Effective discourse depends on how well the educator can create a situation in which those participating have full information; are free from coercion; have equal opportunity to assume the various roles of discourse (to advance beliefs, challenge, defend, explain, assess evidence, and judge arguments); become critically reflective of assumptions; are empathic and open to other perspectives; are willing to listen and to search for common ground or a synthesis of different points of view; and can make a tentative best judgment to guide action. These ideal conditions of discourse are also ideal conditions of adult learning and of education. Transformative learning requires a form of education very different from that commonly associated with children. New information is only a resource in the adult learning process. To become meaningful, learning requires that new information be incorporated by the learner into an already well-developed symbolic frame of reference, an active process involving thought, feelings, and disposition. The learner may also have to be helped to transform his or her frame of reference to fully understand the experience. Educators must assume responsibility for setting objectives that explicitly include autonomous thinking and recognize that this requires experiences designed to foster critical reflectivity and experience in discourse. Education that fosters critically reflective thought, imaginative problem posing, and discourse is learner-centered, participatory, and interactive, and it involves group deliberation and group problem solving. Instructional materials reflect the real-life experiences of the learners and are designed to foster participation in small-group discussion to assess reasons, examine evidence, and arrive at a reflective judgment. Learning takes place through discovery and the imaginative use of metaphors to solve and redefine problems. To promote discovery learning, the educator often reframes learner questions in terms of the learners current level of understanding. Learning contracts, group projects, role play, case studies, and simulations are classroom methods associated with transformative education. The key idea is to help the learners actively engage the concepts presented in the context of their own lives and collectively critically assess the justification of new knowledge. Together, learners undertake action research projects. They are frequently challenged to identify and examine assumptions, including their own. Methods that have been found useful include critical incidents, metaphor analysis, concept mapping, consciousness raising, life histories, repertory grids, and participation in social action (Mezirow and Associates, 1990).

TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING: THEORY TO PRACTICE

11

These methods encourage critical reflection and experience in discourse. The focus is on discovering the context of ideas and the belief systems that shape the way we think about their sources, nature, and consequences, and on imagining alternative perspectives. In fostering self-direction, the emphasis is on creating an environment in which learners become increasingly adept at learning from each other and at helping each other learn in problem-solving groups. The educator functions as a facilitator and provocateur rather than as an authority on subject matter. The facilitator encourages learners to create norms that accept order, justice, and civility in the classroom and respect and responsibility for helping each other learn; to welcome diversity; to foster peer collaboration; and to provide equal opportunity for participation. The facilitator models the critically reflective role expected of learners. Ideally, the facilitator works herself out of the job of authority figure to become a colearner by progressively transferring her leadership to the group as it becomes more self-directive. These are familiar concepts in adult education. Transformative learning is not an add-on. It is the essence of adult education. With this premise in mind, it becomes clear that the goal of adult education is implied by the nature of adult learning and communication: to help the individual become a more autonomous thinker by learning to negotiate his or her own values, meanings, and purposes rather than to uncritically act on those of others. This goal cannot be taken for granted; educational interventions are necessary to ensure that the learner acquires the understandings, skills, and dispositions essential for transformative learning. Critical reflection, awareness of frames of reference, and participation in discourse become significant elements in defining learning needs, setting educational objectives, designing materials and methods, and in evaluating learner growth using nontraditional methods such as portfolios.

Conclusion

From the perspective of transformation theory, the nature of adult learning implies a set of ideal conditions for its full realization that may serve as standards for judging both the quality of adult education and the sociopolitical conditions that facilitate or impede learning. From the perspective of transformation theory, there are ideal conditions for the full realization of adult learning; these conditions can serve as standards for judging both the quality of adult education and the sociopolitical conditions that facilitate or impede learning. The position here is that there is an inherent logic, ideal, and purpose in the process of transformative learning. The process involves transforming frames of reference through critical reflection of assumptions, validating contested beliefs through discourse, taking action on ones reflective insight, and critically assessing it. This understanding of the nature of significant adult learning provides the educator with a rationale for selecting appropriate educational practices and actively resisting social and cultural forces that distort and delimit adult learning.

12

TRANSFORMATIVE LEARNING IN ACTION

References

Cranton, P. Understanding and Promoting Transformative Learning: A Guide for Educators of Adults. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1994. Cranton, P. Professional Development as Transformative Learning: New Perspectives for Teachers of Adults. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1996. Gonzi, A., and others. Key Competencies in On the Job Training. Sydney: University of Technology and Science and Department of Industrial Relations, Employment and Training, 1995. Habermas, J. The Theory of Communicative Action. Vol. 1: Reason and the Realization of Society. Boston: Beacon Press, 1981. Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1991. Mezirow, J. Transformative Theory of Adult Learning. In M. Welton (ed.), In Defense of the Lifeworld. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995. Mezirow, J. Contemporary Paradigms of Learning. Adult Education Quarterly, 1996, 46 (3), 158172. Mezirow, J., and Associates (eds.). Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1990. Stein, S. Equipped for the Future: A Customer Driven Vision for Adult Literacy and Lifelong Learning. Washington, D.C.: National Institute for Literacy, 1995. U.S. Department of Labor. What Work Requires of Schools: A SCANS Report for America 2000. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1991.

JACK MEZIROW is emeritus professor of adult education, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Transformative Learning TeoryDocumento16 pagineTransformative Learning Teoryvisual18100% (2)

- David Harvey, Heritage Pasts and Heritage PresentsDocumento16 pagineDavid Harvey, Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presentsvisual18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Read The Book or Watch The MovieDocumento8 pagineRead The Book or Watch The Movievisual18100% (1)

- The Ideological Antecedents of The Rolls-Royce RadiatorDocumento17 pagineThe Ideological Antecedents of The Rolls-Royce Radiatorvisual180% (1)

- This Sentence Is FalseDocumento232 pagineThis Sentence Is Falsevisual18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Paleolithic Art StudiesDocumento25 paginePaleolithic Art Studiesvisual18Nessuna valutazione finora

- 0352 31601102109GDocumento10 pagine0352 31601102109GDemobilisani NacionalistaNessuna valutazione finora

- American Film As American CultureDocumento22 pagineAmerican Film As American Culturevisual18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Exhibition LabellingDocumento4 pagineExhibition Labellingvisual18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Stojimirov Zlatni PecatDocumento7 pagineStojimirov Zlatni Pecatvisual18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Belting Contemporary Art As Global ArtDocumento27 pagineBelting Contemporary Art As Global Artvisual18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ways of Interpreting MythDocumento7 pagineWays of Interpreting Mythvisual18100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Solomon05 TifDocumento19 pagineSolomon05 TifdevilroksNessuna valutazione finora

- PSYDocumento4 paginePSYSaqib AkramNessuna valutazione finora

- NLP CourseDocumento2 pagineNLP CourseRonaldo MofuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Art of Flourishing by Jeffrey B. Rubin, PH.D - ExcerptDocumento35 pagineThe Art of Flourishing by Jeffrey B. Rubin, PH.D - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group50% (4)

- Genet HailuDocumento77 pagineGenet HailuBrook LemmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)Documento22 paginePosttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)kodi gitalindoNessuna valutazione finora

- Travel Dreams Tourists Guests Geotagging Function InstagramDocumento3 pagineTravel Dreams Tourists Guests Geotagging Function Instagramalif hezreelNessuna valutazione finora

- Bion A Theory of Thinking PDFDocumento5 pagineBion A Theory of Thinking PDFSanja DjordjevicNessuna valutazione finora

- Self-Efficacy Leadership Applying CognitiveDocumento12 pagineSelf-Efficacy Leadership Applying CognitivePadmavathy KNessuna valutazione finora

- Analytic Approaches To Aesthetics (Oxford Bibliography)Documento15 pagineAnalytic Approaches To Aesthetics (Oxford Bibliography)Wen-Ti LiaoNessuna valutazione finora

- 2096 6089 1 PBDocumento19 pagine2096 6089 1 PBEdith Cynthya Villagra ApazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Redacted ComplaintDocumento8 pagineRedacted ComplaintHelen BennettNessuna valutazione finora

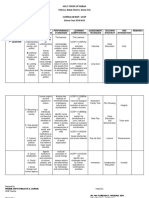

- DAILY LESSON LOG OF M10AL-Ia-1 (Week One-Day One)Documento3 pagineDAILY LESSON LOG OF M10AL-Ia-1 (Week One-Day One)Maricel F. VillafuerteNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Philosophy - Sample 1Documento18 pagineTeaching Philosophy - Sample 1Frederick PatacsilNessuna valutazione finora

- Research QuestionsDocumento4 pagineResearch QuestionsAllyeah Bethel GrupoNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivational Theory PDFDocumento36 pagineMotivational Theory PDFminchanmonNessuna valutazione finora

- Holy Cross of Babak Villarica, Babak District, Samal CityDocumento3 pagineHoly Cross of Babak Villarica, Babak District, Samal CityFibi Gwiin Polet CuanasNessuna valutazione finora

- NHRD Journal On Change ManagementDocumento128 pagineNHRD Journal On Change Managementsandeep k krishnan100% (18)

- Higher-Order Thinking Skills of Junior High School StudentsDocumento8 pagineHigher-Order Thinking Skills of Junior High School StudentsQing Qing ZhangNessuna valutazione finora

- 360 Performance EvaluationDocumento2 pagine360 Performance EvaluationgollasrinivasNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction: Critical Approaches To Tesol: TESOL QUARTERLY Vol. 33, No. 3, Autumn 1999Documento20 pagineIntroduction: Critical Approaches To Tesol: TESOL QUARTERLY Vol. 33, No. 3, Autumn 1999Rogério TilioNessuna valutazione finora

- 1994 Tone Strategic Planning As If Ethics MatteredDocumento19 pagine1994 Tone Strategic Planning As If Ethics Matteredangela bucheliNessuna valutazione finora

- Complete Instructor Manual Bauer Erdogan Organizational Behavior 2.0Documento202 pagineComplete Instructor Manual Bauer Erdogan Organizational Behavior 2.0Rabia Jamil100% (1)

- PORTFOLIO Alternative AssessmentDocumento25 paginePORTFOLIO Alternative AssessmentJoanne Lian Li FangNessuna valutazione finora

- Eval of Preceptor - Erin New HireDocumento2 pagineEval of Preceptor - Erin New Hireapi-266263821Nessuna valutazione finora

- Productive Homework PDFDocumento12 pagineProductive Homework PDFJames FarnhamNessuna valutazione finora

- Halliday Functional Grammar JournalDocumento8 pagineHalliday Functional Grammar JournalYnne Noury100% (1)

- Full PaperDocumento71 pagineFull PaperMarc Joseph LumbaNessuna valutazione finora

- Assure Lesson Plan ThereseDocumento3 pagineAssure Lesson Plan Thereseapi-316263732Nessuna valutazione finora

- Updated Conflict Management and Resolution (Group5)Documento14 pagineUpdated Conflict Management and Resolution (Group5)Andryas AbebeNessuna valutazione finora