Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Sphor, K. (2011) - Contemporary History

Caricato da

Serge VargasDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Sphor, K. (2011) - Contemporary History

Caricato da

Serge VargasCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Journal of Contemporary History http://jch.sagepub.

com/

Contemporary History in Europe: From Mastering National Pasts to the Future of Writing the World

Kristina Spohr Readman Journal of Contemporary History 2011 46: 506 DOI: 10.1177/0022009411404583 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jch.sagepub.com/content/46/3/506

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Journal of Contemporary History can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jch.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jch.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Jul 21, 2011 What is This?

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Article

Contemporary History in Europe: From Mastering National Pasts to the Future of Writing the World

Kristina Spohr Readman

London School of Economics, UK

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3) 506530 ! The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0022009411404583 jch.sagepub.com

Abstract Debates surrounding the approach to and distinctiveness of contemporary history qua history that had been simmering ever since the professionalization of history in the late nineteenth century re-emerged with vigour after 1990. This article attempts to identify what characterizes and distinguishes (the history of) our present time, by comparing the evolution of what has been labelled contemporary history in France, Germany and Britain over the last 90 years. In discussing some of the conceptual problems and methodological challenges of contemporary history, it will be revealed that many in Europe remain stuck in an older, national (and transnational) fixation with the second world war and the nazis atrocities, although working in medias res today appears to point to the investigation of events and phenomena that are global. The article will seek to make a fresh suggestion of how to delimit contemporariness from the older past and end with some comments on the significance of the role of contemporary history within the broader historical discipline and society at large. Keywords contemporary history, global, transnational, Zeitgeschichte

. . . it is the business of the historian, looking back over events from distance, to take a wider view than contemporaries, to correct their perspectives and to draw attention to developments whose long-term bearing they could not have expected to see. For the most part, they have made little use of their opportunity; indeed, it seems as though they are in danger of being frozen forever in the patterns of thought of the years 193345. Georey Barraclough1

1 This quote contains Geoffrey Barracloughs handwritten amendments to p. 27 of the original edition of his Introduction to Contemporary History (London 1964) which he wished to make for the 1967 Corresponding author: Kristina Spohr Readman, International History Department, LSE, London WC2A 2AE, UK Email: K.Spohr-Readman@lse.ac.uk

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

507

The end of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet empire saw the declassication of decades of archival material from many Eastern European countries, most notably East Germany, as well as the release of selected Western documents. This opening of the archival oodgates had a major impact on historical scholarship. History had rapidly moved into real-time. The sheer volume of literature published during the rst post-Cold War decade and beyond shows that many took the opportunity to study the most recent past.2 Yet this development also brought the problematique concerning historians distance temporal and ideological from their object of research to the fore, just as it had been debated after the rst and second world wars.3 Furthermore, the social, political and cultural repercussions of such major changes as the events of 198991 and the technological revolution of the 1980s and 1990s (digitalization and the internet) meant that historians in the naughties could look upon the twentieth century at large from a new perspective and study it in new ways. This context of a world and discipline in ux fostered the re-ignition of the much older and wider professional controversy among historians as to what contemporary history actually was, how it should be practised and what its ends were. Were the new ruptures of 198991 or subsequently 2001 relevant for the elds periodization? And in which ways should contemporary history today relate to the historical discipline at large, to society and to politics? It is signicant that the institutionalization and acceptance of contemporary history within the academy was still a relatively recent development and that, especially in Europe, these processes had been tied to very specic national circumstances and trajectories. Indeed, contemporary history (on the continent especially) had served many states postwar political projects of fostering democracy and thus had a purpose: political and individual decision-making was to be informed by a through understanding of the recent past. Since the 1950s, then, the subjects of the second world war and nazism in particular had come to dominate the works of those who called themselves contemporary historians. Over the past 20 years, however, the theme of the national mastering of the past has been superseded as the most immediate political and public concern by the growing sense of an evolution towards an intensifying and accelerating integration of the worlds societies and states. And, I would argue, it is this phenomenon contemporary historians ought to grapple with.

Pelican edition, but which were not permitted by his publishers C.A. Watts & Co. I wish to thank N.N. Barraclough for lending me the annotated book. 2 Journalistic books, official histories and memoirs form the bulk of this literature. See Michael Cox, Another Transatlantic Split? American and European Narratives and the End of the Cold War, Cold War History, 7, 1 (2007), 12146; Kristina Spohr, German Reunification: Between Official History, Academic Scholarship and Political Memoirs, Historical Journal, 43, 3 (2000), 86988. 3 Particularly after the second. See Astrid M. Eckert, The Transnational Beginnings of West German Zeitgeschichte in the 1950s, Central European History, 40, 1 (2007), 66.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

508

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)

The present article, with Britain, France and Germany as its central European reference points, has three aims: rst, to set the scene, I will briey trace the evolution of the nature and position of contemporary history in the context of the historical disciplines professionalization in the nineteenth century. Second, the circumstances in which contemporary history emerged as a recognized sub-discipline after 1945 will be explored, along with how and why the eld evolved so strictly within and remained for so long wedded to very nationally-conceived parameters. Finally, by examining Charles Maiers and Geo Eleys dierent attempts at re-dening the fundamental global changes that aected the twentieth-century world and by re-evaluating the thought of Georey Barraclough, which is now almost 60 years old, I seek to re-conceptualize the terms of reference for contemporary history. I propose that contemporary European historians today ought to attempt to transcend the institutional stickiness tied to the obsession with particular, now already older, national pasts and turning points. Instead, their focus should be on the implications of truly working in medias res; and in doing so and by employing all new tools available to them, the emerging task is to write the world as it presents itself today by which I mean producing more transnational or global, and distinctly less Euro-centric, narratives of contemporary aairs. Scholars scepticism towards contemporary history rst originated in the move to professionalize the historical discipline in the nineteenth century, when Leopold von Ranke pushed for the establishment of history as a Wissenschaft. Ranke argued that the proper business of the historian was not judging the past, . . . [and] instructing the present for the benet of future ages, as the semi-professional historians had previously done, but rather establishing how it actually was (wie es eigentlich gewesen ist). The strict presentation of the facts . . . is undoubtedly the supreme law, he wrote.4 This emphasis on objectivity to establish authority led to the creation of a common standard for historical scholarship, which in turn demanded certain qualications from the historian.5 Writing scholarly history could not be about ones own experiences and eyewitness accounts, but the methodological breakthrough was seen to be in the systematic examination of surviving written sources from the past. The new professional history, as promoted by German scholars (including Ranke, Barthold G. Niebuhr and Johann G. Droysen), then, excluded contemporary history in its truest sense. Indeed, even Heinrich von Treitschke, considered by many as the nineteenth-century German contemporary historian par excellence, was no exception: at his death in 1896 his History of Germany in the Nineteenth Century only reached up to 1847. Still, this is not to claim that Droysen, Treitschke and others were not at all presentist in their

4 See Fritz Stern (ed.), The Varieties of History (London 1956), 5462, esp. 57. 5 J.L. Gaddis, On Contemporary History: An Inaugural Lecture Delivered before the University of Oxford on 18 May 1993 (Oxford 1995), 911; Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The Objectivity Question and the American Historical Professsion (New York 1988), 218, 5160.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

509

writing. While they took their professional legitimization as serious scholars of history from the archives, they were nevertheless commenting on contemporary aairs not least by using some of their studies of the past as a means to inuence the direction of present-day politics, as, for example, Droysen intended with his Geschichte der preussischen Politik in support for the Hohenzollerns rule. The problem that arose from such presentist works was twofold: the openly political agenda and outlook coloured the interpretations of the past, while none of the historians in question were actually experts in contemporary history per se.6 In general, serious historical research in Germany now had a rm orientation towards the past and past politics and the relations between states, in particular. The focus on the critical study of primary sources, especially government papers, conrmed this trend towards the predominance of political and diplomatic history. To be sure, while private archives remained mostly inaccessible, post-Rankean historians beneted from the opening of state or royal archives, which were both growing in numbers and increasingly professionally run, as well as from the boom in the publication of selected (but hardly ever contemporary) government documents by Royal Commissions. But governments were obviously driven by a political self-interest in histories that fostered their nation-building drive.7 In at least one important way, this development towards the professionalization of history was revolutionary. Since the beginnings of what has been considered serious historical writing, history had been indissolubly linked to the present and historys use had always been seen as being a means to improve the understanding of the present. Thucydides History of the Peloponnesian War8 provided the archetype. It had been written with the conviction that future generations would better understand their own times if they knew as much as possible about the authors own. This was signicant because, as much as Thucydides work is praised as the most ancient example of serious history, he wrote about events through which he lived. Ironically, Thucydides work can hence also be used as a prime exemplar of contemporary history, as advocates of the eld have always pointed out.9 Similar analogies can also be made with, for example, Guiccardinis, Macchiavellis or Gibbons works. In fact, in the centuries between Thucydides and Ranke many considered contemporary history to be best history.10 With the rise of the German

6 On the professionalization of history in Germany and its wider consequences for the discipline across Europe, see John Burrow, A History of Histories (London 2009), 45366. See also the essays by Sebastian Manhart and Friedrich Jaeger in Horst Walter Blanke (ed.), Historie und Historik: 200 Jahre Johann Gustav Droysen (Cologne 2009), 3872, 10629. 7 Kasper Risbjerg Eskildsen, Leopold von Rankes Archival Turn: Location and Evidence in Modern Historiography, Modern Intellectual History, 5, 3 (2008), 42553. See also, for example, Harold Temperley and Lillian M. Penson, A Century of Diplomatic Blue Books, 18141914 (Cambridge 1938). 8 Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War (Chicago 1989). See also Bernard Williams, Truth and Truthfulness: An Essay in Genealogy (Princeton, NJ 2002), ch. 7. 9 R.W. Seton-Watson, A Plea for the Study of Contemporary History, History, 14 (April 1929), 4; Gavin Henderson, A Plea for the Study of Contemporary History, History, 26 (June 1941), 523; Gaddis, Contemporary History, op. cit., 6. 10 Timothy Garton Ash, History of the Present: Essays, Sketches and Despatches from Europe in the 1990s (London 1999), x; Seton-Watson, Plea, op. cit., 4. See also Matthias Peter and Hans-Ju rgen Schro der, Einfuhrung in das Studium der Zeitgeschichte (Paderborn 1994), 1920, 26.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

510

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)

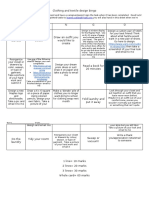

Table 1. Contemporary History Articles in the main History Journals between 1990 and 2005 Articles on the Periods No. of all Articles English Historical Reviewz Historical Journaly Historyz Past and Presentz Historische Zeitschriftz Revue Historiquey American Historical Reviewy Journal of Modern Historyz 277 565 219 395 296 328 276 226 190045 41 122 32 62 44 33 70 83 194670 11 29 10 5 6 13 12 12 19712005 1 3 1 1 2 0 4 1 Other 224 411 176 327 244 282 190 130

The table is based on the authors own research and calculations. y articles and historiographical reviews (no review articles, notes and documents, debates, and fora) z articles only (no review articles, notes and documents, debates, and fora) The article category Other denotes that these articles span other centuries and/or span parts of all three periods indicated. It is also noteworthy that the majority of articles in the 19461970 column appeared mostly during the early 2000s.

historical school, for the rst time, scholarly history became largely detached from the present. Following Rankes philosophy, achieving sucient insulation from contemporary concerns had emerged as the historians highest endeavour. Crucially, this standpoint was not only a matter of the overall historiographical ethos of Rankeans. Their understanding of the role of reliable sources in historical research and hence their xation with written archival documents, which were simply not to be had for the most recent past, explains why contemporary history developed the way it did. The export of these German ideas on the nature and practice of academic history across Europe and to the United States during the nineteenth century meant that contemporary history was pushed to the fringes of historical scholarship. Until well into the twentieth century it was conned to the areas of popular memory and historians political engagement, as well as to the works of popular historians and journalists. And while the size of the historical profession was to grow, and university syllabi thematically and methodologically were to diversify,11 many, even today, consider it precipitate and over-hasty to write history while it is still smoking, to quote Barbara Tuchmann. A glance at the list of articles published in some of the main general history journals in Britain, France, Germany and the USA during the last one and a half decades (19902005) reveals that the tendency of virtually ignoring

11 Tosh, In Pursuit of History (Harlow 2000), 7190; John Catterall, What (if anything) is Distinctive about Contemporary History?, Journal of Contemporary History, 32, 4 (1997), 446; Peter Steinbach, Geschichte und Politik nicht nur ein wissenschaftliches Verha ltnis, Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, B28 (2001) [web-archive], 15.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

511

Table 2. Contemporary History Articles in the specialized European Contemporary History Journals between 1990 and 2005 Articles on the Periods No. of all Articles Journal of Contemporary Historyz Contemporary European Historyz Contemporary British Historyz Vierteljahrshefte fu r Zeitgeschichtez Revue dHistoire Moderne et Contemporainez 463 200 311 231 486 190045 282 94 41 108 68 194670 112 76 144 81 41 19712005 16 24 93 18 11 Other 53 6 33 24 366

The table is based on the authors own research and calculations. z articles only (no review articles, notes and documents, debates, and fora) The article category Other denotes that these articles span other centuries and/or span parts of all (or at least two) periods indicated. It also includes biographical and methodological articles.

the most recent past is widely spread (see Table 1). Of course, one might expect more contemporary research on the 1950s than the 1980s, given that these journals are dedicated to covering the breadth of the historical profession both in terms of elds and epochs. Yet, it is the scale of the decline in article numbers the closer we move to the present that is striking, and crucially this slide becomes all the more evident when looking at the contents of specialist journals on contemporary history (see Table 2). As Eric Hobsbawm argued in 1992, retrospective is the historians secret weapon, because retrospective is the chronological distance which stabilises his perspective.12 This was very much in line with R.G. Collingwoods view, expressed in 1924. He wrote that it is only after close and prolonged reection that we begin to see why things happened as they did, and to write history instead of newspapers.13 Yet, crucially, Hobsbawm also pointed out that historians today needed as he himself did to write about the most recent past, too: to provide future historians with a good picture of our time, and with a view to preserving source material that, while abundant and varied, is increasingly ephemeral.14 Contemporary history rst began to re-establish itself in the European and American historical professions after the rst and second world wars. With both scholars and governments looking for explanations of the events of the previous two decades, the eld soon became institutionalized as a sub-discipline of history in West Germany, France, Britain, America and elsewhere in the western hemisphere. Yet the label contemporary history denoting a sub-discipline as much as being a reection of a particular epoch was inconsistently used, and its multiple

sent, in Institut dHistoire du Temps Pre sent 12 Eric Hobsbawm, Un historien et son temps pre ` Franc [IHTP] (ed.), Ecrire lhistoire du temps present En hommage a ois Bedarida (Paris 1993), 102. 13 R.G. Collingwood, Speculum Mentis or: The Map of Knowledge (Oxford 1924), 82. 14 Hobsbawm, Historien, op. cit., 102.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

512

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)

interpretations only added to the conceptual and methodological confusion about this eld qua history that has persisted until the present day.15 In dierent countries, historians allocated very dierent meanings to what they called contemporary history. Evidently these denitions were bound up with national histories and traditions. In France, even if quite serious scholars wrote about the 1789 revolution relatively soon after the events and thus deed German historiographical trends, lhistoire contemporaine became established (and institutionalized) in historical scholarship with Ernest Lavisses Histoire de France contemporaine, published in 192022. His ten-volume edition covered the period from the French Revolution of 1789 to the Peace of Versailles in 1919.16 The current ditions du Seuil series Nouvelle Histoire de la France contemporaine likewise E reaches from the French Revolution to the late twentieth century.17 And as Robert Gildeas and Anne Simolins 2008 volume Writing Contemporary History proves, the events of 1789 are considered by many French historians as a major historical caesura still aecting contemporary France, and specically as the starting point of Frances modern or contemporary era.18 Indeed, if we consider the recent controversies in French politics, including criticism of former colonial ` -vis ethnic minorities in the hexagon, the signicance of policies or the policies vis-a the institutional and normative heritage of the revolution for Frances self-image pubbecomes obvious. Or as Serge Bernstein put it: Pour la culture politique re licaine, tout commence en 1789.19 This explains why the concept of contemporariness in France embraces some two hundred years. Yet over the last 30 or 40 years, Vichy France and de Gaulles presidency have equally installed themselves as narrower temporal and thematic bounds for the study of French contemporary history.20 The classication lhistoire contemporaine has hence increasingly been related to two very dierent stretches of time, a practice which Franc ois darida criticized as ambiguous and misleading. Be darida however directed his Be criticism less against the above-mentioned contemporary periods in French history as such, but against the distortion of what he believed to be the true meaning of the word contemporary.21

Re mond, Quelques questions de porte e ge ne rale en guise dintroduction, in IHTP, Ecrire, 15 Rene op. cit., 2733. 16 Ernest Lavisse, Histoire de France contemporaine, depuis la revolution jusqua` la paix de 1919 (Paris 192022). Cf. Pierre Nora, Lhistoire de France de Lavisse, in Nora, Les Lieux de memoire, vol. I (Paris 1986), 31575. 17 Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine (Paris 1972), the first volume being by Michel Vovelle, La chute de la monarchie, 17871792 (Paris 1972) and the currently last (19th) volume being by Jean Jacques Becker in collaboration with Pascal Ory, Crises et alternances: 19741995 (Paris 1998). 18 Robert Gildea and Anne Simolin (eds), Writing Contemporary History (Oxford 2008). 19 Serge Bernstein, Les cultures politques en France (Paris 1999), 114. de lhistoire du temps pre sent, in Dossier: Lhistoire du temps 20 See Pieter Lagrou, De lactualite present, hier et aujourdhui, (July 2000), 5, http://www.ihtp.cnrs.fr/spip.php%3Farticle470&langfr. html (last accessed 9 January 2011). darida, France, in Anthony Seldon (ed.), Contemporary History: Practice and Method (Oxford 21 Be sent in Frankreich: Zwischen nationalen 1988), 12930. Cf. Rainer Hudemann, Histoire du temps pre ffnung, in Alexander Nu Problemstellungen und internationaler O tzenadel and Wolfgang Schieder (eds), Zeitgeschichte als Problem: Nationale Traditionen und Perspektiven der Forschung in Europa [Sonderheft Geschichte und Gesellschaft] (Go ttingen 2004), 175200.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

513

darida was a strong defender of Hans Rothfels idea that ones In eect, Be own time should be synonymous with what is considered to be contemporary.22 darida A forceful advocate of studying truly contemporary aairs, in the 1970s, Be introduced a new classication: lhistoire du temps present (history of the present), with which he wanted to indicate a much shorter time-frame of the recent past.23 Yet in practice the new term has merely been used as a synonym for what others call lhistoire contemporaine. The French Institut dhistoire du temps present (IHTP), darida in 1978, is a case in point. Its research, though intended to founded by Be focus on the years after 1945, especially decolonization, has centred primarily on Vichy France (and the questions related to French resistance and/or collaboration with nazi Germany). What is hence predominantly associated with lhistoire du temps present is an epoch starting with the second world war as a major historical rupture that is seen as inuencing present politics and society. In terms of methodological innovation, it is noteworthy that research on the Vichy syndrome brought to the fore Pierre Noras concept of the lieux de memoire, a concept which has signicantly inuenced and shaped historical scholarship both at home and abroad.24 As in France, thanks to Lavisse, in Germany contemporary history was already practised during the 1920s, where the eld unfolded specically as a critical response to Germanys asserted war guilt (as it was ocially stated in the Versailles Treaty). Public demand for better knowledge and the political elites interest in justifying their own actions before and during the rst world war had led to an early declassication of selected diplomatic correspondence by Germany (as well as the Soviet Union, France and England) which spawned an unprecedented surge of historical literature, especially of ocial histories.25 Despite methodological questions over the issue of proper distance in their very contemporary research, the unprecedented access to archival documents seemed to satisfy traditional historians of the validity of their colleagues work, not to mention the acceptability of the historico-political motivation of those contemporary historians who wrote about the Weimar Republic.26

darida, Le temps pre sent, Espaces Temps, 29, 1er trimestre (1985), 11. As to the concept of ones 22 Be sent, in IHTP, Ecrire, op. cit., 589; Timo Soikkanen own time, cf. Serge Bernstein La lacune du pre (ed.), Lahihistoria: teoriaan, metodologiaan ja lahteisiin liittyvia ongelmia (Turku 1995), 1068; Peter and Schro der, Einfuhrung, op. cit., 1517, 314. ` ses sur le thymologie du temps pre sent, in 23 Michel Trebitsch, La quarantaine et lan 40: Hypothe Ecrire, op. cit., 65. 24 Nora, Les Lieux de memoire, op. cit. 25 Johannes Lepsius, Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy and Friedrich Thimme (eds), Die grosse Politik der europaischen Kabinette 18711914 (Berlin 192227); E. Adamov (German edn by K. Kersten and B. Mironow), Die grosse Politik der Ma chte im Weltkrieg aus den Geheim-Archiven der Entente (Dresden 193032); A. von Wenger (ed.), Bibliographie zur Vorgeschichte des Weltkrieges (Berlin 1934); G.P. Gooch, Recent Revelations of European Diplomacy (London 1940); and earlier, Idem, History of Modern Europe, 18781919 (London 1923); H. Temperley and G. P. Gooch (eds), British Documents on the Origins of War, 18981914 (London 192638); Documents Diplomatiques Franc ais, 18711914 (Paris 192959). Cf. W. Pick, Contemporary History (Oxford 1949), 757; SetonWatson, Plea, op. cit., 910. 26 See Peter and Schro der, Einfuhrung, op. cit., 23. Cf. Arthur Rosenberg, Die Entstehung der deutschen Republik (Berlin 1926).

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

514

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)

As a scholarly term, the designation Zeitgeschichte (re-)appeared with vigour after the second world war in (West) Germany, and Hans Rothfels in 1953 put forward the now classic denition of contemporary history as the epoch of those living and its treatment by academics. But he also designated 1917 as the starting point for contemporary history, for a universal-historical epoch27 an epoch in which foreign policy was driven by domestic, especially societal concerns. He further specied the present as a time of coexistence of two ideologically opposed political camps in East and West, yet with this antagonism simply following from other longer-term historical antagonisms.28 Thus, from the outset Rothfels denition embodied a conicting dualism: the idea of uid temporal boundaries (with a generational component and an openness to constant rejuvenation) versus the idea of a new universal (or global) epoch from 1917 onward. This embodied an international, or rather transnational, not purely German national, outlook. The establishment in 1947 of the Institut zur Erforschung der nationalsozialistischen Politik (Institute for Research on National Socialist Politics) in Munich, renamed in 1952 as the Institut fur Zeitgeschichte (IfZ, Institute of Contemporary History), institutionalized Zeitgeschichtsforschung (research on contemporary history), specically research on the nazi regime and the second world war. The IfZ, as a separate research institute, acted initially on the periphery of the universities, and only by the early 1980s had the number of West German university chairs in Zeitgeschichte or neueste Geschichte risen from one in 1954 to 31, thus reecting the sub-disciplines solid establishment in the university sector.29 From its inception, West German contemporary historical research bore a political purpose, as the young Bonn Republic tried to build a democratic civic culture. Indeed, this postwar political culture was to be shaped by lessons learned from the past. They searched for answers, initially to how the 1945 catastrophe had come about and how to rise from it, and then later on why and how the fall of democracy and the ascendancy of Hitler, the second world war and the Holocaust had been possible. With these questions in view, West German contemporary historians including Rothfels, Theodor Schieder, Werner Conze and later Martin Broszat and Hans-Ulrich Wehler investigated the politics and society of the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich. They pointed to the law of objectivity in the study of archival sources, while avoiding any discussion or even explicit expression of their own involvement and contemporariness in the nazi era. Only from the 1980s did historians of contemporary aairs also begin to explore West German

27 Hans Rothfels, Zeitgeschichte als Aufgabe, Vierteljahrshefte fur Zeitgeschichte, 1, 1 (1953), 18, esp. 2, 6, 7. 28 Jan Eckel, Hans Rothfels: Eine intellektuelle Biographie des 20. Jahrhunderts (Go ttingen 2005), 3013. 29 Ralph Jessen, Zeithistoriker im Konfliktfeld der Vergangenheit, in Konrad H. Jarausch and Martin Sabrow (eds), Verletztes Gedachnis: Erinnerungskultur und Zeitgeschichte im Konflikt (Frankfurt a. M. 2002), 156, 168.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

515

postwar politics; and from German unication in 1990, the entire East German past.30 This is not to say that after the 1950s the study of truly contemporary aairs was not considered desirable in principle. Indeed, Rothfels himself, in spite of his dual denition, had been keenly urging the necessity of studying and analysing events that lay only ve, ten, fteen or twenty years in the past.31 Over the last couple of decades popular history has certainly engaged with current aairs; and over the last few years scholarly history has in important and original ways even begun to explore the major domestic and international socio-economic and political shifts of the 1970s and early 1980s, not least as new socio-cultural research trends have led to studies of westernization and modernization.32 Nonetheless, historical practice shows that those who consider themselves as contemporary historians in (West) Germany have primarily tended to keep their research topics in line with the declassication of archival material. And here, leaving aside GDR and reunication history which is possible due to exceptional circumstances, a lot of research remains concentrated on nazism, the second world war and Weimar Germany as pivotal, if not dening, twentieth-century moments and developments. This, compounded by Hitlers omnipresence in the media and in national memory politics, might be seen as paralysing the evolution of German contemporary history to some extent. Considering that even the recent dual reappraisal of the past (brown and red, as well as Eastern and Western) has kept German historians essentially focused on their nation-state and perhaps inadvertently promoted an inward-looking approach, the discipline of Zeitgeschichte in Germany has perhaps not moved forward as much in time and scope as it ought to have done.33 It is undeniable of course that nazism had a signicant impact on the postwar (West) German nation just as East German communism has had since 1990 on unied Germanys society and politics. The culture of remembrance on

30 Norbert Frei, The Federal Republic of Germany, in Seldon, Contemporary History, op. cit., 122 9; Idem, Farewell to the Era of Contemporaries: National Socialism and Its Historical Examination En Route into History, History and Memory, 9, 12 (1997), 5979; Hartmut Kaelble, La Zeitgeschichte: sent, in IHTP, Ecrire, op. cit., 838. On the lhistoire allemande et lhistoire internationale du temps pre relationship between the first generation of German contemporary historians, studying nazi Germany as an object of research and the place of the nazi era in their own, personal biography, see Mathias Beer, Der Neuanfang der Zeitgeschichte nach 1945: Zum Verha ltnis von nationsozialistischer Umsiedlungs- und Vernichtungspolitik und der Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ostmitteleuropa, in Winfried Schulze and Otto Gerhard Oexle (eds), Deutsche Historiker im Nationalsozialismus (Frankfurt a. M. 1999), 274301; Mathias Beer, Wo bleibt die Zeitgeschichte? Fragen zur Geschichte einer Disziplin, 20 March 2003, http://hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de/forum/typediskussionen&id293 (last accessed 9 January 2011). 31 Hans-Peter Schwarz, Die neueste Zeitgeschichte: Geschichte schreiben, wa hrend sie noch qualmt, Vierteljahrshefte fur Zeitgeschichte, 51, 1 (2003), 6. 32 See Konrad Jarausch, Das Ende der Zuversicht? Die siebziger Jahre als Geschichte (Go ttingen 2008); Anselm Doering-Manteuffel and Lutz Raphael, Nach dem Boom: Perspektiven auf die Zeitgeschichte seit 1970 (Go ttingen 2008). Cf. Andreas Ro dder, Die Bundesrepublik Deutschland 19691990 (Mu nchen 2003). 33 Christoph Klessmann and Martin Sabrow, Contemporary History in Germany after 1989, Contemporary European History, 6, 2 (1997), 21922, esp. 221; Konrad H. Jarausch and Thomas Lindenberger (eds), Conflicted Memories: Europeanizing Contemporary Histories (New York and Oxford 2007), 119.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

516

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)

a societal and political level to take the public controversy over the Holocaust memorial in Berlin in the 1990s or over Gu nter Grass revelations of his SS past in his autobiography of 200634 as two examples has been and still is a clear reection of this. It also shows that the past, history, is seen as something that could and should be brought into the service of contemporary aairs.35 Yet it is a paradox that German historians and the IfZ, being increasingly distant from their object of research, should still refer to the nazi era as contemporary history. It would perhaps seem more logical to classify 19331945 as part of the realm of general (or modern) history, while pointing however to its ghostly presence within contemporary politico-cultural debate.36 And this historicizing may also deal with the problem of the early 2000s tide of retrospective self-victimization of Germans as suerers of war and expulsion, arising from the recent fashion of analysing personal recollections and recovering authentic visualizations of the past that seem to have swept away the critical confrontation with the nazi past.37 Hans-Peter Schwarz has attempted to come to grips with this specically German denitional muddle of Zeitgeschichte that is so deeply entwined with institutional frameworks. In 2003 he suggested the introduction of a new term neueste Zeitgeschichte (newest contemporary history) to denote the most recent past, by which he meant the (post-Cold War) epoch, starting in the late 1980s. With this he seemed to follow Karl Dietrich Bracher, who in 1978 had supported an epochal view with reference to German practice, labelling the period 191445 altere Zeitgeschichte and the post-1945 era neuere Zeitgeschichte.38 But thus far, Schwarzs proposal seems to have made no wider impact, with the label neueste Zeitgeschichte failing to become institutionalized among the historical profession.39 It is unsurprising, then, that the IfZs journal Vierteljahrshefte fur Zeitgeschichte (founded in 1953 by Rothfels), like the institute itself, continues to shy away from publishing any research GDR and reunication history apart beyond the magical archival threshold of 30 years. In Britain, contemporary history as a eld of academic study also came into existence after the rst world war. Before then, neither contemporary English political history nor general history (meaning European history) was taught at universities. In 1914, the Oxford modern history syllabus still excluded post-1837

34 Gu ttingen 2006). nter Grass, Beim Hauten der Zwiebel (Go 35 Martin H. Geyer, Im Schatten der NS-Zeit, in Nu tzenadel and Schieder (eds), Zeitgeschichte als Problem, op. cit., 2553. 36 On historicism and historicization, see Martin Broszat, Nach Hitler: Der schwierige Umgang mit unserer Geschichte (Munich 1986); Dan Diner, Ist der Nationalsozialismus Geschichte? Zu Historisierung und Historikerstreit (Frankfurt a. M. 1987); cf. Philippe Burrin, Lhistorien et l historisation, in IHTP, Ecrire, op. cit., 7788; and Jo rn Ru sen, The Logic of Historicization: Metahistorial Reflections on the Debate between Friedla nder and Broszat, History and Memory, 9, 12 (1997), 11344. 37 Norbert Frei, 1945 und wir: Das Dritte Reich im Bewusstsein der Deutschen (Munich 2005), 722. 38 Ludmilla Jordanova, History in Practice (London 2000), 40; Tosh, In Pursuit, op. cit., 33; Schwarz, Die neueste Zeitgeschichte, op. cit., 25, fn. 99. Hans Gu nter Hockerts, in turn, has defined GDR history as dritte Zeitgeschichte: see Hans Gu nter Hockerts, Zeitgeschichte in Deutschland: Begriff, Methoden, Themenfelder, Historisches Jahrbuch, 113 (1993), 127. 39 Schwarz, Die neueste Zeitgeschichte, op. cit., 8.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

517

British political history and post-1878 European history. Contemporary British and European history simply lay outside the scope of exact scholarship.40 Yet English university historians did not use the strict classication rules of the archives as a pretext for their reluctance to study more recent topics. Rather, as Llewellyn Woodward pointed out, they defended their view (following Rankean lines of argument) by claiming that recent events could not be seen in the proper perspective; it was necessary to know what had happened next, and next meant then at least two or three generations.41 This is not to say that no English historians wrote about the most recent past. Sir John Seeleys The Expansion of England (1883)42 had connected current aairs and history, covering English colonialism from the eighteenth century up to the 1870s. But Seeley was something of an exception, at least within the academy. Moreover, he was less a historian (despite holding the Chair of Regius Professor of History at Cambridge University) than a classicist. Overall, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a professional objection to contemporary (British) history was predominant. As R.W. Seton-Watson argued, it was an [un]worthy subject for the true historians pen because of its incompatib[ility] with the detachment and calm of academic life.43 The two world wars pushed the Rankean doctrine rapidly into the background at least for a short time. With the early release of archival material, as well as oral evidence by many witnesses, the issue of necessary distance seemed forgotten. Shelves of government-sponsored ocial histories, as well as other contemporary histories were published after 1919 and also after 1945. Regarding the latter caesura, it is signicant to note that British historians, together with their American counterparts had the unique opportunity to be rst in sifting through nazi papers that Allied troops had seized in 19445, before they were returned to the West German government in the late 1950s and early 1960s. As Astrid Eckert has explained, by writing German Zeitgeschichte contemporary British (and American) historians were actually involved in a transnational, rather than national endeavour that was to last for decades to come.44 Crucially, in both postwar eras historians such as Hugh Seton-Watson, Gavin Henderson and J.W. Pick45 wrote about the methodological problems and denitions of, as well as justications for, writing contemporary history. In 1950 the Recent History Group, with A.J.P Taylor and Alan Bullock, was founded in Oxford. Soon, however, a certain traditionalism was to dominate again within the academy: the scientic and objective approach of studying the past in isolation from the present regained prestige and inuence among professional historians. This meant that research

40 Llewellyn Woodward, The Study of Contemporary History, Journal of Contemporary History, 1, 1 (1966), 12. 41 Ibid., 4. 42 Sir John Robert Seeley [ed. and with an introduction by John Gross], The Expansion of England (Chicago 1971). 43 Seton-Watson, Plea, op. cit., 2. 44 Eckert, The Transnational Beginnings, op. cit., 87. 45 See F.W. Pick, Contemporary History: Method and Men, History, 31 (March 1946), 2655.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

518

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)

on the rst world war, as well as the 1920s and 1930s became taboo, at least until a number of years after 1945. Interestingly, economic historians, and specically the new breed of business historians that emerged in the 1940s and 1950s, were less worried about making contemporary issues their object of research, as a closer look at articles published in the Business History Review reveals. Scholars working in the dominant sphere of political or diplomatic history, by contrast, had to consider not only the right temporal perspective a necessity for good history, but also the practical obstacle of the classication rules that governed the release of archival sources. In the 1940s, the latest British documents available for consultation in the Public Record Oce were dated 1885 (with the exception of the selected pre-released sources on the rst world war); during most of the 1950s the date was 1902. With the Public Records Act of 1958, most documents 50 years old were to be released on a year-by-year basis; and it was not until 1967 that the Wilson government amended the declassication rule to 30 years. Although a distance of three decades remained, the new Act brought the front line of history closer to the present.46 In this light, it does not seem very surprising that discussion on contemporary history as a respectable sub-discipline of history arose among British historians during the 1960s. Apart from the less stringent classication rules of British archives, the decline of the British Empire, the rise of new political actors such as the European Communities and the changes in the political, social and technological environment of the Cold War world also played a major role in the evolution of the discipline of history, and especially in reawakening an interest in contemporary history in Britain, as new circumstances needed to be explained. Notably, a new postwar generation of academics in Britain and abroad increasingly conducted research in the social sciences (sociology, political science, international relations theory, government studies and others). Borrowing from their ideas and methods and inuenced by the developments in the world around them, historians also embarked on new types of history. These new fashionable branches included social history (or the history of social structure), gender history, history of science, urban history and intellectual history.47 It was in the context of these developments in the historical discipline and in the context of social sciences dealing legitimately with the very recent past and even current aairs that contemporary history and in particular contemporary social history was (re-) discovered by historians.48 Indeed, in this epoch the Institute of Contemporary History was founded (1965) and the Journal of Contemporary History (1966) launched. Both seemed to give the eld of contemporary history more weight and credibility though it is noteworthy

46 Brian Brivati, Julia Buxton and Anthony Seldon (eds), The Contemporary History Handbook (Manchester 1996), xixii; Seldon, Contemporary History, op. cit., 120. 47 Arthur Marwick, The New Nature of History: Knowledge, Evidence, Language (Basingstoke 2001), 12444; Steinbach, Geschichte und Politik, op. cit., 3. 48 Peter and Schro der, Einfuhrung, op. cit., 28. See also Donald Cameron Watt, Contemporary History in Europe (London 1969); Bernard Krikler and Walter Laqueur (eds), A Readers Guide to Contemporary History (London 1972).

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

519

that Institute and Journal had their roots in the Wiener Library in London, which had grown from the personal library of a Jewish immigrant, Dr Alfred Wiener. Signicantly, from the outset the Institutes and Journals focus was on Europes fascist past and specically nazism. Bearing in mind the dierent implications of Zeitgeschichte and histoire contemporaine, what did historys contemporariness really mean to the British? According to Arthur Marwick in 1968, British contemporary history was dominated by a notorious colourlessness. There were no Soviets, no concentration camps, no resistance movements to be explored.49 Or, to put it another way, Britain and British society did not seem to have endured a similarly disruptive and trenchant national caesura in 1945, if compared with the traumas the Germans and French had gone (and were still going) through. In the UK, there was simply no need after the war for contemporary historians to engage in a process of confronting and overcoming an illiberal political system or in (re-) building the nation and public memory. Britains development as a polity had, after all, remained largely unaffected. Thus, from the late 1940s to the mid-1960s, British contemporary history lived something of a wallower existence. At a time when the social sciences were in ascendancy and when the very nature and practice of history was the object of intense debate among historians most prominently E.H. Carr and G.R. Elton50 Georey Barraclough wrote the now classic study An Introduction to Contemporary History (1964). For Barraclough, contemporary history was synonymous on a content-level with a history of a changing world, because as he put it the forces shaping [contemporary history] cannot be understood unless [one is] prepared to adopt worldwide perspectives. Interestingly, Barracloughs point of departure was the realm of politics, which he combined with socio-economic discussions of industrialization and technological advancements and ideas on the decline of the West. Focused on broad structural changes as he aimed for a universal perspective, he eectively conceptualized global history as contemporary history as opposed to contemporary history in a national framework. He insisted that his approach was not about supplementing our conventional view of the recent past by adding a few chapters on extraEuropean aairs, but re-examining and revising the whole structure of assumptions and preconceptions on which that view was based.51 Barraclough then suggested that contemporary history had to be understood as dierent in quality and content from what historians commonly referred to as modern history.52 He advocated a great divide of two ages the modern and the contemporary believing that, following a period of transformation or watershed after 1890, the start of a new contemporary or post-modern era (not

49 Arthur Marwick, The Impact of the First World War on British Society, Journal of Contemporary History, 3, 1 (1968), 55. 50 E.H. Carr, What is History? (Basingstoke 1961); G.R. Elton, The Practice of History (London 1967). 51 Geoffrey Barraclough, An Introduction to Contemporary History (2nd edn, London 1967), 10. 52 Ibid., 10.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

520

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)

to be confused with the concept of postmodernity in philosophy) began in late 1960 or early 1961.53 Barraclough chose this precise date because the onset of John F. Kennedys presidency indicated to him that a new generation, not involved in pre-1939 politics and not conditioned by pre-war attitudes and experiences, was coming into power.54 Unfortunately for Barraclough, his perception was premature: after Kennedys assassination, a series of men born early in the twentieth century, not least Ronald Reagan, won US presidential elections. Apart from Barracloughs chronological divisions, what is astonishing about his concept of the new contemporary age is that he considered the term contemporary history colourless, as he expected this new, contemporary age to be renamed ex post facto at a major turning point sometime in the future. Thus, although used to indicate an age, or epoch, he did not introduce contemporary history as a permanent label for one specic period.55 Historians have mostly disagreed with Barracloughs equation of contemporary history with the new post-modern age, as well as the latters precise starting date(s). Yet Barracloughs book was a pioneering work for the eld; and in the British context it created a theoretical prole for the subject. In hindsight, his peers even credited him with contextualizing the fundamental change of world politics in the twentieth century. Even if his concept of a new contemporary age, with reference to the conventional threefold division into ancient, medieval and modern has not found support, historians today tend to treat the decades between 1945 and 1990 as a period of its own with very distinct and novel features. For many in Britain, the Cold War and beyond, coined by some also as the postwar era, rather than nazism and the era of the second world war, became associated with the eld of contemporary history; indeed, a new specialist Institute of Contemporary British History (established in 1986) was to focus on postwar British domestic and foreign policy, the Commonwealth and decolonization. Interestingly, a number of eminent European historians have made their take on contemporary history synonymous with a specic classication of the twentieth century: Eric Hobsbawm in Age of Extremes referred to the short twentieth century (19141991) which is marked by signicant historical ruptures; Henry Rousso wrote about the hypothetical long twentieth century (19502020), which he dened in relation to the idea of ones lifetime; and Tony Judt in his Postwar pointed to an era of memory construction and remembrance (1945 2005) whilst proposing for Europe, 60 years after Auschwitz, nally to historicize its past.56 Following such epochal logic, British (as much as German and French) university courses have increasingly referred to history since 1945 or twentieth-century

53 Ibid., 10, 2930. 54 Ibid., 29. 55 Ibid., 21, 23. 56 Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century (London 1994); Henry Rousso, sent, vingt ans apre ` s, in Dossier: Lhistoire du temps present, hier et aujourdhui Lhistoire du temps pre (July 2000), 45, http://www.ihtp.cnrs.fr/spip.php%3Farticle471&langfr.html (last accessed 9 January 2011). See also Jordanova, History, op. cit., 128; Peter and Schro der, Einfuhrung, op. cit., 37.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

521

history as contemporary history.57 The undergraduate and postgraduate history papers that include such a contemporary component do indeed go up to Thatcher or even Blair (for British history) or up to the end of the Cold War and even further, to the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks, or the decision-making processes in the run-up to the second Iraq war in 2003 (for International or European history), although the weighting of course bibliographies tends to lie with the preand immediate post-1945 decades. Curiously, a similar tendency can be observed when looking at the major Journals dedicated to contemporary history (see Table 2). The Journal of Contemporary History, which subscribed to the broader Rothfelsian idea of contemporary history, announced in its rst issue (1966) that The eld of study and discussion of the Journal will be Europe in the twentieth century, and has continued to publish primarily work on the two world wars and the interwar period. This pattern can also be detected for the German Vierteljahrshefte fu r Zeitgeschichte, and even the Revue dHistoire Moderne et Contemporaine, most articles from which admittedly cover the fteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The newer British journals Contemporary European History and Contemporary British History (launched in 1992 and 1987 respectively) fare somewhat better, with near-equal numbers of articles on topics from the 19141945 era, and the early Cold War period in the former and the majority of articles in the 194670 bracket in the latter. It should also be noted, when assessing the gures in the second-to-last column, that most articles in this category published in the JCH, CEH, VfZ and RHMC focus on Eastern European and Soviet issues and specically the collapse of communism; the exception is CBH, where British electoral politics and Thatcherism seem to be the dominant theme. Of course, the exceptional early availability of documentary evidence from the former Soviet bloc was justication enough for the objectivists, and gave history and historians an excuse to study these recent political events soon after they had happened. The usual second Rankean objection to contemporary history, the issue of (sucient) temporal distance, was overridden. Yet it could be argued that, in spite of their position as witnesses of the events, scholars have been comfortable researching the era, of the Cold War and the even longer period of Soviet communism because these had become history in the conventional sense, in that as historical phases or phenomena they could be considered over.58 Of course, the same argument has been turned on its head, as in the case of Germanys nazi past, and even today the second world war era is perceived as not over, because contemporary witnesses survive and those events still aect present-day German aairs. How, then, do we characterize the contemporariness of contemporary history today? What are its distinguishing features?

57 See Vanessa Ann Chambers, Informed By, but Not Guided By, the Concerns of the Present: Contemporary History in UK Higher Education Its Teaching and Assessment, Journal of Contemporary History, 44, 1 (2009), 89106. Cf. Anthony Seldon, The Theatre of Contemporary History, in Idem (ed.), Contemporary History: Practice and Method (Oxford 1988), 11718. 58 See Juhana Aunesluoma and Pauli Kettunen (eds), The Cold War and the Politics of History (Helsinki 2008).

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

522

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)

And what does this mean for how we think about and might do contemporary history in the twenty-rst century? The end of the Cold War prompted numerous historians across Europe to categorize the events of 198991 (the fall of communism and of the Soviet empire, together with the new Maastricht Treaty) as constituting a historically important recent rupture and indicating the beginning of a new historical epoch:59 the postCold War phase qua contemporary history. For some today this post-Cold War phase the beginning of which US president George H.W. Bush had originally heralded with his speech on a new world order on 11 September 199060 has already ended, too. John Gaddis stated:

We have never had a good name for it, and now its over. The post-Cold War era let us call it that for want of any better term began with a collapse of one structure, the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, and ended with the collapse of another, the World Trade Centers Twin Towers.61

As the post-Cold War phase recedes into the postwar era or the even longer duree of twentieth-century history, for Gaddis at least the naughties seem to epitomize the contemporary time. These recent denitions of contemporary history, derived from a specic chronology, can be seen as growing out of the tradition in which other, earlier caesurae, such as the now famous Stunde null or 1917, have been identied as starting points for new, contemporary ages. To be sure, dierent national traditions have tended to date contemporary history according to specic circumstances in their national pasts. But we have to accept that, for the last few decades, there has existed among contemporary historians across (Western) Europe a strong 1930s and 1940s, if not to say nazi-centric, historiographic xation. Other attempts to frame the contemporary in terms of chronology, but referring to more generic features of any recent age which only acquires a clearer label by hindsight, have ranged from Finnish historian Yrjo Blomstedts rather rigid, indistinctive sources-bound idea of a no mans land that keeps rolling on between the present and what is traditionally considered (in political history at least) the documented (archival) past,62 to the more ambiguous or looser statements with an emphasis on uidity, dynamism and open-endedness.63 The latter were implied darida and others, who as part in the interpretations of Rothfels, Laqueur, Be

, op. cit., 3. 59 Soikkanen, Lahihistoria, op. cit., 11112; Lagrou, De lactualite 60 George Bush, Address Before a Joint Session of the Congress on the Persian Gulf Crisis and the Federal Budget Deficit (11.9.1990), http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/public_papers.php?id 2217&year1990&month9, (last accessed 19 September 2008). 61 Quotation from Schwarz, Die neueste Zeitgeschichte, op. cit., 9. 62 Soikkanen, Lahihistoria, op. cit., 105; Yrjo Blomstedt, Historian rintama, Valvoja, 16 (1964), 346; Lauri Hyva ma ki, Uusimman historiamme tutkimuskysymyksia: Oman ajan historia ja politiikan tutkinta (Helsinki 1967). sent entre histoire et sociologie, in IHTP, Ecrire, op. cit., 50. 63 Dominique Schnapper, Le temps pre

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

523

of their broader denitions (including also epochal vantage points) determined the timeframe of contemporary history as ones own time. This lifetime obviously diers from individual to individual depending on their age, and generations overlap. Or, to use Hans Gu nter Hockerts metaphor: contemporary history is a ausgedehnter Bahnhofsbereich, in dem kurze und lange Zuge aus verschiedenen Richtungen nach sehr unterschiedlich langer Fahrtdauer eintreen.64 Hockerts rened conception of ones own time by denition an un-datable period that embodied by default a certain conict of [multiple] contemporary histories, as Karl Dietrich Bracher had put it two decades earlier could be expanded to include numerous past events, structures and experiences that aect or are part of our present-day lives, and are anchored in the consciousness of the contemporary witness, in the personal and cultural memory. Today, this would indeed mean (in the German case, which incidentally both Hockerts and Bracher use as their reference point) the inclusion of the rst world war, Weimar, the nazis and the Cold War, with the turning points of 1945 and 198990. Not only are some still alive to have witnessed the earlier events, but (say) the current teenage generation may just still be a secondary witness via rst-hand accounts of contemporary witnesses. Moreover, the latter is certainly also being aected through the societal culture of memory (as reected in exhibitions, new memorials and memorial days, lms and broadcasts) and the governments Geschichtspolitik.65 This particular generational approach, then, poses a problem. Apart from being in its conception, and with reference to its starting point, very personal and national at once, it eectively covers most of the twentieth century, much of which (especially research on fascism, nazism and communism) historians now also study as serious Vergangenheitsgeschichte, the history of the past. (A look back to the 1980s Historikerstreit and the question of historicization [Historisierung] which of course equally aects Cold War or, here, East German History serves as a reminder.)66 To put it another way, the older (pre-1945) contemporary history keeps breaking into the newer, ensuring that the past is part of the present. And even if we leave this conundrum by itself, it is worse that those who call themselves contemporary historians at present have, in practice, tended to become stuck in the early phases of their lifetime and even in a time prior to it, instead of exploring the unfolding events and developments at the front line of their time (as Rothfels had suggested). In other words, rejuvenation has come to a halt. This is not solely based on a particular understanding of (the nature of) contemporary history, given the elds specic postwar political mission which, over time, has created a certain institutional stickiness. It is also linked perhaps to a certain dedication to the Rankean rules of historicism: temporal (and implicitly ideological) distance and the use of traditional (written) sources. Such methodological

64 Hockerts, Zeitgeschichte, op. cit., 127. (Translation of quote: an extended station concourse where short and long trains arrive after very varying journey times from different directions.) 65 Christoph Klemann, Zeitgeschichte als wissenschaftliche Aufkla rung, Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, B5152 (2002), 10. 66 Ru sen, Logic, op. cit., 11344.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

524

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)

conservatism needs revising if we are to rebalance the early lifetime and to widen the elds thematic scope. This is not to suggest that historical research on truly current aairs has been non-existent. A glance at recent publishers lists of new historical monographs and history textbooks proves the opposite. However, these works, the majority of which have been undertaken in the area of contemporary political and international aairs, reect the rather traditional approaches of political and international history. It is possibly easier and more tempting to study recent wars and certain relatively closed episodes in current political aairs (such as the First and Second Gulf Wars, Yugoslavian Wars, Thatcherism, Blairism and New Labour, transatlantic relations, activities of the international institutions (EU, NATO and UN), the evolution of post-Soviet Russia)67 where there appear to be more obviously detectable starting, turning and end points; indeed, where a specic shorter-term sequence of events can be identied, isolated and treated as a closed episode; and for which sources (including ocial documents, oral history and memoirs) are possibly more easily identiable. By contrast, there are signicantly fewer studies exploring ongoing cultural, social, economic and other (longer-term) phenomena, where tendencies of development might be more dicult to detect and where it is more dicult to seek to establish the signicance and direction of emergent trends and evolutionary processes, or possibly to identify them as recurrent patterns. Yet, the problems of studying near-un-discernible long-term trends should not cause historians to avoid even trying, not least because multidimensional macrolevel phenomena such as climate change, the globalization of marketized economic development, the international banking crisis, terrorism, mass migration and the multi-ethnic society, human rights and pop culture, are crucial in characterizing our contemporary time. Most prominently, Charles Maier and Geo Eley have recently advocated what could be called a thematic-chronological approach, with globalization as its central theme, in an attempt to identify from todays perspective what makes the contemporary era (and thus implicitly its history) stand out. Charles Maier has taken issue with existing temporal delimitations, in particular the periodization expressed with the label twentieth-century history. In its stead he has proposed an alternative chronological narrative: one built around territoriality. Looking back, he has suggested that what we have been witnessing for the last two to three decades is the contemporary dissolution of structural order. This allows

67 See for example, Kenneth Dyson and Kevin Featherstone, The Road to Maastricht: Negotiating Economic and Monetary Union (Oxford 1999); Brendan Simms, Unfinest Hour: Britain and the Destruction of Bosnia (London 2001); Steven Fielding, The Labour Party: Continuity and Change in the Making of New Labour (Basingstoke 2002); Antony Seldon and Dennis Kavanagh, The Blair Effect, 20015 (Cambridge 2005); Richard English, The Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA (Basingstoke 2003); Kristina Spohr Readman, Germany and the Baltic Problem after the Cold War: The Development of a New Ostpolitk, 19892000 (London 2004); Geir Lundestad, Just Another Major Crisis? The United States and Europe since 2000 (Oxford 2008). For textbooks, see E.H.H. Green, Thatcher (London 2006); Stephen Lovell, Destination in Doubt: Russia since 1989 (London 2006); , The Padraic Kenney, The Burdens of Freedom: Eastern Europe since 1989 (London 2006); Ilan Pappe Israel/Palestine Question: A Reader (London 1999).

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

525

researchers to glimpse trends formerly so ubiquitous they had not been perceived as issues in historical investigation. Maier argues that it was between 1860 and 1970 that spatially anchored structures for politics and economics were taken for granted. Now this territoriality is disappearing. And this might mean two things for how we understand and look at the present: rst, that way has been given to the rise of culture or civilization as a replacement for space, and here international or community conict will be at stake. Indeed, with the collapse of the territorial we are all virtual neighbours, and culture might thus end up as the trope for all group frictions that can never be transcended. Or, second, that there might be the desire to deploy political regulation to control the globalized economy. In other words, supranational agglomerations like the EU might provide the territorial base for political intervention; though this might dilute cultural cohesion and hence cause a populist backlash, expressed through the longing for a smaller and closed identity space.68 Geo Eley in turn has taken the language of globalization as a starting point and reection of our time; he has identied two ways in which the term is currently being used: as a category of ordinary language which circulates in the public sphere as a claim and as a demonstrable social fact (the supposed structural primacy of global integration) that really exists. Eley himself is most interested in an analysis of the ideology or discourse of globalization, by which he means the insistence on globalization as the organizing reality of the emerging international order and the crystallizing of specic practices, policies and institutions around that insistence. Indeed, he refers to his undertaking as historicizing the global. While fully accepting the critique of some, that globalization in the sense of integrating dierent parts of the world into one can be traced all the way to the fteenth century and, we could add, this process did not at all stages originate from Europe he rst highlights the frequent use of the term in the current policy discourse. Secondly, he posits that we are witnessing new (post-1960s) forms of exploitation of labour in what he has identied as our globalized, post-Fordist economies of the capitalist world. Yet he also points to the signicant development of the demise of the global option for the colonial, neo-colonial and post-colonial non-Western world of anti-imperialist sovereignty that disappeared with the USSR in 1991, and to the subsequent (and parallel) developments of an accelerating and intensifying integration of the worlds societies and states. Finally, he takes issue with globalization as a political project that brings to the fore the following tensions: global governance versus global civil society, US hyperpower versus anti-globalization (even anti-capitalist) Leftist grassroots lobby, Europe or Western civilization versus the Muslim world, to name but a few.69

68 Maier, Consigning the Twentieth Century to History: Alternative Narratives for the Modern Era, The American Historical Review, 105, 3 (June 2000), 47 pars, at par. 43, http://www.historycooperative. org/journals/ahr/105.3/ah000807.html (last accessed 19 September 2008). 69 Geoff Eley, Historicizing the Global, Politicizing Capital: Giving the Present a Name, History Workshop Journal, 63 (2007), 15488. On cycles of globalization from the sixteenth century onwards, see Adam McKeown, Periodizing Globalization, History Workshop Journal, 63, 1 (2007), 21830.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

526

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)

Both Maier and Eley in their dierent ways have grappled with the notion of globalization in describing what they consider the distinctive feature of the present. There is, however, the danger of over-emphasizing one single aspect, such as globalization, as the sole characteristic of our present time. Firstly, globalization as presented by Maier and Eley cannot simply be isolated as the general theme and generic feature of, and by implication denition for, todays or tomorrows contemporary history although at present this aspect might seem to stand out in our lives, and thus appear more real to publics, scholars and political elites than it was even in Barracloughs time. Secondly, there is the problem that the simple process of globalization is not new: it can be interpreted as one of the key components of the making of the modern world (Christopher Bayly). Either way, it is ultimately problematic to derive an overarching denition of contemporary history primarily from the character of an epoch; just as the choice of a precise starting point (related to specic historical ruptures, such as 1917, 1945, 198990 or 2001) to circumscribe what is actual seems too rigid. Despite these caveats, I would like to advocate a more global or transnational narrative of contemporary aairs, given the fresh impulses that the recent growth of these historiographical trends (intended as approaches overcoming national as much as methodological boundaries within a fragmented historical discipline and across related social sciences) have oered to historians. Barraclough, and to some extent Rothfels, developed their denitions in rather dierent circumstances from those of the present, but both sketched the outlines of a contemporary history that was global in scope and universal in approach avant la lettre, so to speak. It was, however, a vision that European contemporary historians failed to fully embrace. In terms of conceptualization, let us revisit Barracloughs musings. He had held that Contemporary History begins when the problems which are actual in the world today rst take visible shape.70 What are we to make in 2011 of this statement? From his vantage point in the early 1960s, Barraclough identied 18901960 as marking a watershed period between the modern and contemporary ages, and thus eectively delimited the historical hinterland of contemporary aairs and framed a distinctive contemporary period. His statement can, however, be seen as carrying useful insights into how contemporary history might be thought about and practised today, and dened for the future. Leaning on Barraclough, I want to postulate, rstly, that the principal distinguishing feature of contemporary history (in the truest sense of the term) is surely that its practitioners will write in medias res about events and developments that are perceived as actual and central to presentday life, as perceived by publics and political elites, and the outcome of which might still be uncertain. It is this denition of instantaneity that forms the chronological core of recentness. Secondly, in order to illuminate this uncertain present, contemporary historians need not only work from a certain starting point forward, exploring temporal causalities, contingency and agency of their object of research. They must also look backwards for explanatory depth to

70 Barraclough, Introduction, op. cit., 12.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

Spohr Readman

527

said historical hinterland of events and the roots of developments indeed, as far back as necessary. If, in this vein, we then really concern ourselves with what our actual problems are, I propose that the contemporary historians long obsession be it in Britain, France or Germany with the second world war or nazi Germany as the beginning of our present concerns has to be left behind (allowed to simply grip us . . . as memory,71 as Charles Maier put it). Looking at the nature of our highly interconnected and increasingly globalized contemporary world in terms of communication, human interaction, economics, politics and culture contemporary historians will have to move beyond their Euro-centric perspective and their xation on themes of the past so deeply entwined with a national mastering of the past, that seems to have dominated contemporary historiographies in Europe for the last few decades. For example, the internet has had wider implication for society at large. It has brought humans across the globe together in a virtual environment, as a global community. This raises questions about the categories of locality, identity, citizenship and state, as well as about power structures, and how real and virtual environments and identications can co-exist. While the global context, with its emphasis on interactions at all levels, perhaps matters more today than in the past in our shrunk worldwide terrain, the above does not mean that we should discard studies of the local, regional or national, or micro-processes in favour of macro-approaches.72 Rather, our horizons must be broadened to engage in innovative ways with the wide range of issues in the present, which also means confronting the reality of the growing speed with which things have been changing since the 1970s and certainly since the 1990s, and considering the new ways in which history is being recorded. The revolution in information technology (the internet and digitalization) over the last two decades is immensely signicant.73 Today a wealth of contemporary source material, including ocial government documents (parliamentary debates, speeches, treaties, etc.), poll data, newspapers, magazines, lm and photo documents, collections of personal testimonies, journals and so on is stored in electronic archives and even accessible via the internet. Tracing, analysing and explaining the very recent past imposes peculiar and novel challenges to historians, not least as much communication takes place online, via email, blogs, twitter and other electronic means and networks. As much as access is instant and global, a drawback is that web-(re)sources can be ephemeral. Moreover, contemporary historians do not simply have to ask themselves which methods of source critique are to be applied in evaluating these materials, but, crucially, how the new media might have aected, for example, decision-making processes and whether decisions or events are still

71 Charles Maier, Consigning the Twentieth Century to History: Alternative Narratives for the Modern Era, The American Historical Review, 105, 3 (June 2000), 47 paragraphs, here par. 43, http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ahr/105.3/ah000807.html (last accessed 19 September 2008). 72 Cf. Michael Gehler, Zeitgeschichte zwischen Europa isierung und Globalisierung, Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, B512 (2002), 2335. 73 Cf. Hartmut Voit, Voru berlegungen zu einer Didaktik der Zeitgeschichte, Zeitschrift fur Geschichstdidaktik (2002), 717, esp. 9.

Downloaded from jch.sagepub.com at UNIV AUTONOMA AGUASCALIENTES on July 23, 2013

528

Journal of Contemporary History 46(3)