Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Uncertainity

Caricato da

Sehrish KayaniTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Uncertainity

Caricato da

Sehrish KayaniCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

Adverse-selection versus signaling: evidence from the pricing of Chinese IPOs

Dongwei Su

Department of Finance, Jinan University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510632, PR China Accepted 28 July 2003

Abstract Because of the high economic uncertainty inherent in the privatization process, nancial markets in China are characterized by large information asymmetry. Using data of 587 rm-commitment initial public offerings (IPOs) between January 1994 and December 1999, I investigate whether IPO underpricing is related to pre-IPO information asymmetry and whether and to what extent underpricing serves as a signal of rm quality. I nd that: (1) Underpricing is correlated with proxies of ex ante uncertainty, including the size of offerings, insider ownership, disclosure practice, market conditions and allocation mechanism. (2) To some extent, underpricing can be explained in terms of a strategy for rms to signal their value to investors. However, the market-feedback hypothesis has more explanatory power than the signaling hypothesis. My empirical results are largely consistent with winners curse and signaling models. 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

JEL classication: G15; G32; P34 Keywords: Initial public offerings; Asymmetric information; Chinese stock markets

1. Introduction The initial public offering (IPO) market is an important channel for capital allocation. From the viewpoint of nance research, IPO underpricing in the sense of abnormal short-run returns on IPOs is commonly perceived as a contradiction to capital-market efciency. Loughran, Ritter, and Rydquist (1994) provide international evidence on IPO underpricing.

Tel.: +86-592-218-0636. E-mail address: tdsu@jnu.edu.cn (D. Su).

0148-6195/$ see front matter 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jeconbus.2003.07.001

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

They argue that underpricing may be caused by basic problems derived from microeconomic uncertainty and information asymmetry, and is likely to depend upon institutional peculiarities inherent in an IPO market. Rock (1986) and Beatty and Ritter (1986) see the explanation of the phenomenon in the winners curse that uninformed investors face. Informed investors always bid for securities that are underpriced. The relatively uninformed investors are aware of the possibility that they would tend to receive a greater portion of the overpriced issues than informed investors would. Thus, IPOs must be sufciently underpriced to compensate uninformed investors for the ex ante uncertainty or adverse-selection bias. In general, the higher is the ex ante uncertainty on the value of an IPO, the higher the expected underpricing will be. Several empirical studies, including Koh and Walter (1989), Keloharju (1993), and Michaely and Shaw (1994), have found evidence consistent with the winners curse explanation. Allen and Faulhaber (1989), Grinblatt and Hwang (1989), and Welch (1989) model signaling games in which ownermanagers (insiders) know the true value of the rm while potential investors (outsiders) do not. IPO underpricing is deliberate and voluntary to signal a rms true value, and is justied to achieve better prices in subsequent seasoned equity offerings (SEOs). Using US data, Jegadeesh, Weinstein, and Welch (1993) test the signaling hypotheses by assessing the likelihood of an SEO as a function of IPO underpricing. They only nd weak evidence that rms that underprice their IPOs are more likely to issue seasoned equities and on average have larger SEOs. Garnkel (1993) tests the signaling hypothesis by examining the probability of insider selling as a function of IPO underpricing. He nds no correlation, casting further doubt on the signaling models. However, Su and Fleisher (1999) test the models using early Chinese IPO data by investigating whether there exists an optimal signaling schedule relating a rms intrinsic value and degree of underpricing. They obtain empirical results consistent with the signaling explanations. In this paper, I apply winners curse model and examine the empirical relationship between IPO underpricing and proxies for ex ante information uncertainty in China. I also apply signaling models and investigate whether underpricing is a deliberate signal of rm quality. In doing so, I carefully relate a rms SEO behavior to IPO underpricing by analyzing whether a more underpriced rm is more likely to issue larger amount of seasoned equities more quickly. My empirical analysis carefully delineates the signaling null versus the market-feedback alternative. When rms underprice to signal quality, the pattern of underpricing should be related to that of SEOs as rms trying to recoup their underpricing costs. Alternatively, factors other than underpricing, such as market timing, can determine the pattern of SEOs. While empirical studies have been carried out previously, these are mainly related to the IPOs in the US and other developed or emerging countries and the results have produced conicting ndings. Economic conditions and institutional framework in China differ signicantly from those in the US and other countries. The conclusions from previous body of IPO research cannot be automatically imputed to China. For example, as noted in the next section, SEOs are much more frequently observed in China than in the US. As another example, insiders (including the government, managers and directors) typically own a much larger percentage of shares than those in the US and other countries. Therefore, the empirical signicance of underpricing signal may differ from that in the US and other countries. In addition, IPO stocks are listed on the two stock exchanges in China straight after completion of

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

the offer. In contrast, IPOs in the US are typically traded in the less visible over-the-counter market. Moreover, because of a lack of accounting and auditing sophistication in China, upper management has incentives to manipulate nancial information. To prevent managers from inating prots or providing false nancial statements, the securities regulatory authorities have set up more stringent requirements for nancial disclosure. In short, Chinese data allow us to examine IPO models in a rapidly developing market that differs substantially from the US in terms of institutional characteristics, market size and sophistication. In this paper, I nd largely consistent empirical results with predictions of adverse-selection and signaling hypotheses. However, I also nd some conicting evidence against existing studies. For example, Su and Fleisher (1999) nd strong evidence that underpricing is a strategy for rms to signal their value to investors. I use a different dataset with different variables (underpricing residual vis--vis raw underpricing) and nd that the market-feedback alternative is a more appealing explanation. Chowdhry and Sherman (1996) argue that time elapsed between IPO date and listing date is a proxy for the extent of information leakage and should be positively related to the degree of IPO underpricing. I nd no such evidence in the Chinese data, probably because subscription information is not a secret during the new issues process and unrelated to the time interval between offering and listing. A lottery mechanism is typical in allocating IPO shares. Investors have a priori knowledge that IPOs must be oversubscribed. The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2, I describe the data and some distinct institutional characteristics about the Chinese IPO market. I also dene variables used in the empirical work. In Section 3, I discuss adverse-selection models and examine the empirical relationship between IPO underpricing and pre-IPO proxies of uncertainty. In Section 4, I discuss signaling models and analyze whether and to what extent underpricing signals rms quality. I contrast the signaling hypothesis to the market-feedback hypothesis and compare their explanatory power. I conclude with a summary of ndings in Section 5.

2. Data and measurement The data consist of 587 rm-commitment domestic A-share IPOs between January 1994 and December 1999. To study the effects of SEOs on IPO underpricing, I also extract a sub-sample of 392 rms that went public between January 1994 and December 1997. The December 1997 cutoff allows two calendar years for a rm to issue seasoned equities.1 A-share IPOs are strictly owned by private Chinese citizens and are freely tradable in RMB in the Shanghai and Shenzhen securities exchanges.2 I exclude foreign-owned B-, H- and N-shares because most of these shares are issued after a rm has been listed in a Chinese

1 IPO date is the day on which the prospectus of the issuing rm appears on China Securities Daily. To allow a rm to issue seasoned equities within a reasonable amount of time, I set a 2-year cutoff date in obtaining My sub-sample. There is nothing special about this cutoff date. I used a cutoff date of 547 calendar days (about one-and-a-half years) in the previous version of the paper and obtained consistent empirical results. 2 RMB, or renminbi, is the ofcial currency in China. In My paper, variables measured by Chinese currency are converted to the US$ using the spot exchange rate. In December 2000, the exchange rate was ofcially managed at about 8.22 RMB per US$.

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

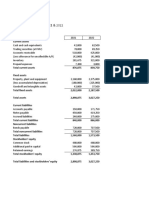

exchange. I believe it is more appropriate to treat newly issued foreign shares as SEOs. In addition to A-shares, there are three more types of domestic shares: government shares, employee shares, and legal entity shares (held by other rms). These three types of shares cannot be traded in the two ofcial exchanges. All share types have identical voting rights (1 share, 1 vote) and equal claims to any and all distributions (dividends and rights offerings). The listing requirements for A-shares are fairly detailed and are designed to achieve a wide dispersion of ownership. Interpreting leverage, protability, and other nancial variables for Chinese rms is very challenging. The traditional Chinese accounting system was brought from the former Soviet Union in early 1950s for the highly centralized economy and was quite different from the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) in the market economies. Different industries have different accounting regulations enforced by their own ministries. On July 1, 1993, the new Enterprise Accounting Standards and Enterprise Financial Accounting Principles came into effect and brought the Chinese accounting practices closer to the international standards. I exclude IPOs before January 1994, so that the pre-IPO nancial variables in the sample of rms are constructed under the new accounting standard. Data on offer prices, number of different types of share offered, the amount of pre-IPO debt, total assets, and other balance sheet items are compiled from the Chinese Futures and Stocks Encyclopedia published by Shanghai Xian Zi Information Corporation. Data on market indices, share prices, trading volume, and spot exchange rates between the US$ and RMB are obtained from Shanghai Shenyin International Securities, Xiamen Branch. All price data are converted to US$. I dene IPO initial return, i.e., the degree of IPO underpricing, as: IPORETN = (P1 P0 )/P0 , where P0 is the initial offering price and P1 is the rst-day market closing price. The mean IPORETN in the sample of 587 rm-commitment domestic A-share offerings between January 1994 and December 1999 is 128.2%. In other words, the rst-day market closing price was on average more than twice as high as the initial price offered to Chinese investors. Many past studies have indicated that IPOs have often been underpriced. Table 1 presents the degree of IPO underpricing for the US, UK and a number of emerging markets.

Table 1 International evidence on IPO underpricing Author(s) Lee, Taylor, and Walter (1996) Aggarwal, Leal, and Hernandez (1993) Clarkson and Merkley (1994) Su and Fleisher (1999) Ljungqvist (1997) Kim, Krinsky, and Lee (1995) Paudyal, Saadouni, and Briston (1998) Aggarwal et al. (1993) Firth (1997) Levis (1993) Ritter (1991) Afeck-Graves, Hegde, and Miller (1996) Country Australia Brazil Canada China Germany Korea Malaysia Mexico New Zealand UK US US Degree of underpricing (%) 11.90 78.50 6.44 948.50 10.57 57.56 62.10 33.00 25.90 14.30 14.06 11.00 Period of study 19761989 19791990 19841987 19871995 19871991 19851989 1995 19871990 19791987 19801988 19751984 19751985 Number of IPOs 266 62 180 308 189 169 95 37 143 712 1526 1183

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119 Table 2 IPO underpricing in China by year of issuance Year 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Number of IPOs 87 20 189 196 100 95

Degree of underpricing (%) 314.5 258.0 93.9 74.5 50.3 56.4

Table 2 presents the degree of underpricing in China by the year of IPO issuance. As shown in these tables, the abnormal return on the rst day of trading is large in China (314.5% in 1994), but decreases over time (56.4% in 1999). Using data of 308 rm-commitment new issues from January 1, 1987 through December 31, 1995, Su and Fleisher (1999) nd that the average A-share IPO underpricing is 948.6%. They attribute the high IPO initial return to Chinas institutional characteristics including a relatively small aggregate supply of shares in the early stage of capital-market development, governments desire to encourage the public to participate in stock markets, bribery, and large information asymmetry. As Chinas institutional settings for new listings improve over time, it is natural to observe smaller degree of average underpricing during the sample period covered in this paper. Other variables used in this empirical work include: IPOSHA: the number of A-shares issued at the IPO date (the publication day of the prospectus in China Securities Daily). IPOVALUE: IPOSHA offer price, proceeds from an IPO (in US$). SEOSHAq : the number of shares issued at the time of an SEO (q = 1, 2, 3). SEOSHAq = SEOSHA

q

SEOVALUE: q SEOSHAq offer price, or the proceeds from all SEOs. TOTALSHA: IPOSHA +SEOSHA +government shares+management and employee shares+legal entity shares, or the total number of shares outstanding. INTRINSC: IPOVALUE + SEOVALUE + book, or face, value of government shares, management and employee shares and legal entity shares, a proxy for rms intrinsic value. INFORMED: the sum of government shares, management and employee shares, and legal entity shares divided by TOTALSHA, or the percentage of shares held by insiders and institutional investors. AFTRETN1: after-market return based on closing prices from the closing of the rst day of trading to the end of the second week of trading. AFTRETN2: after-market return between closing prices from the beginning of the third week of trading to the end of the fourth week. ln AGE: logarithm of the age of a rm in years from the date it was established to the date of its IPO. PROFSHA: calendar years prot prior to the IPO (in US$) divided by the total number of domestic shares at the IPO date. ln TIMEIPO: logarithm of the number of days elapsed between the IPO date and the rst day of market trading. EARNINGS: dummy for earnings forecast, EARNINGS = 1 if the issuer provides earnings forecast in the prospectus, EARNINGS = 0 otherwise. USAGE: dummy for funds usage, USAGE = 1 if the issuer provides disclosure on IPO funds usage in the prospectus, USAGE = 1 otherwise. LEVER-

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

Table 3 International evidence on IPO underpricing Variable Mean Minimum Maximum Number of rms

Full sample of 587 rm-commitment IPOs between January 1994 and December 1999 (as a fraction of rms intrinsic value, %) A-share IPOs 19.38 0.5 85.30 587 Government shares 12.62 0 74.27 422 Legal entity shares 8.14 0 33.85 486 Employee shares 1.04 0 11.20 521 Sub-sample of 392 rm-commitment IPOs between January 1994 and December 1997 (as a fraction of rms intrinsic value, %) A-share IPOs 18.06 0.5 78.33 392 Government shares 13.93 0 74.27 315 Legal entity shares 7.3 0 30.61 323 Employee shares 1.13 0 11.20 366 Seasoned equity 46.62 0 95.1 318 We note that not all rms have government or institutional ownership of shares. However, if a rm does not have government shares, it usually has a large percentage of shares controlled by some legal entities such as state enterprises or institutions.

AGE: the book value of pre-IPO debt (short term and long term) divided by the book value of all assets. MKTRUNUP: cumulative daily returns on the Shanghai/Shenzhen security exchange 30-trading day before an IPO, an indicator for the market conditions surrounding a new issue. RREMSTD: standard deviation of daily returns on the Shanghai/Shenzhen security exchange 30-trading day before an IPO, an indicator for the market uncertainty surrounding a new issue. STD: standard deviation of daily after-market returns estimated over a 100-trading day period after inception of market trading. LD: lottery dummy, LD = 1 if the issuer uses a lottery mechanism in allocating IPO shares, LD = 2 if the issuer uses a xed-price offer with pro-rata allocation on oversubscribed shares, LD = 3 if the issuer uses an auction mechanism with quantity and price bids. EXD: stock exchange dummy, EXD = 1 for a company listed on the Shenzhen Securities Exchange, EXD = 0 for a company listed on the Shanghai Securities Exchange. TIME: variable representing IPO year, which takes the value 1, 2, . . . , 6 for a rm going public in year 1994, 1995, . . . , 1999, respectively. SIC(k): six industry dummies: durable goods (SIC1), non-durable goods (SIC2), transportation and public utilities (SIC3), agriculture (SIC4), services including restaurants, department stores and hotels (SIC5) and domestic and foreign trade (SIC6). Table 3 presents sample statistics for share offerings. Tables 4 and 5 contain sample statistics and correlations for some of the variables used in this paper. As shown in these tables, the government still maintains control in varying degree over many rms. The size of government ownership ranges from 12.62% to 74.27%. Only 165 out of 587 issuers going public between January 1994 and December 1999 do not report government ownership of shares. However, none of these 185 issuers has reported IPO size that is above 50% of its total shares outstanding, indicating that a large portion of its shares is still controlled by other state enterprises. It is also noteworthy in terms of the signaling hypothesis tested in this paper that initial offering size relative to rms intrinsic value is on average 18.06%, which is small relative

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119 Table 4 Descriptive statistics for variable used Variable IPORETN AFTRETN1 AFTRETN2 INFORMED ln AGE PROFSHA ln TIMEIPO LEVERAGE MKTRUNUP PREMSTD STD IPOVALUE INTRINSC Description A-share IPO initial return After-market return in the rst 2 weeks of trading After-market return in the next 2 weeks of trading Fraction of shares held by insiders and institutions Log of years a rm has been in business prior to the IPO Prot per share a year before IPO Log of time elapsed between IPO date and listing date Book value of debt divided by book value of all assets Market return 30-trading day before an IPO Standard deviation of market returns 30 days before IPO Standard deviation of rst 100-trading day returns Proceeds from IPO (in million US$) Proxy for rms intrinsic value (in million US$) Mean 128.2% 0.044% 0.052% 37.5% 2.46 0.22 1.84 0.34 0.31% 2.12% 3.09% 28.83% 163.5% SD 172.6% 0.381% 0.309% 61.6% 0.89 0.47 1.76 0.15 4.33% 1.44% 3.74% 46.4% 246.02% Minimum 52.08% 1.63% 1.42% 11.4% 0.48 0.04 0.49 0.06 13.18% 0.46% 0.68% 1.31% 4.85%

Maximum 692.6% 2.18% 1.75% 84.2% 4.27 1.83 2.63 0.73 29.04% 12.37% 26.25% 385.3% 1292.28%

to SEOs (46.62% on average). In fact, SEOs are frequently observed. About 80% of the Chinese rms (318 out of 392 rms) that went public before December 31, 1997 have issued seasoned equities. By comparison, in the United States, between 1980 and 1986, only about 20% of rms going public issued seasoned equities (Jegadeesh et al., 1993).

Table 5 Correlation matrix for key variables used IPORETN INFORMED PROFSHA LEVERAGE MKTRUNUP PREMSTD STD IPOVALUE ln TIMEIPO 0.428 0.091 0.311 0.383 0.296 0.073 0.526 0.272 MKTRUNUP PREMSTD STD IPOVALUE ln TIMEIPO 0.163 0.02 0.15 0.033 INFORMED 0.027 0.06 0.125 0.114 0.059 0.231 0.069 PREMSTD 0.073 0.086 0.063 PROFSHA LEVERAGE

0.108 0.073 0.059 0.088 0.093 0.004 STD

0.139 0.152 0.006 0.188 0.017 IPOVALUE

0.104 0.028

0.06

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

3. The adverse-selection models Rock (1986) and Beatty and Ritter (1986) propose that there is information asymmetry between informed and uninformed investors. Because quantity rationing instead of price adjustment occurs when there is excess demand for shares, the informed investors crowd out the uninformed investors for allocations of protable issues. The allocations received by uninformed investors are biased toward less-protable issues. Therefore, in order to attract uninformed investors to participate in the IPO market, rms must underprice their IPOs sufciently to allow uninformed investors a reasonable return for their ex ante uncertainty, and to enable them to recover the losses resulting from their purchase of overpriced securities. There are two important empirical implications: (1) Issues in which the public have a priori knowledge that insiders and institutional investors have little or no participation will be less underpriced. The reason is that uninformed investors will not face winners curse and allocation disadvantage, and underpricing will not be required to induce them to participate in the IPO markets. (2) Expected underpricing increases in the ex ante uncertainty surrounding an issue. To examine cross-section variations in the underpricing of Chinese IPOs, I regress the degree of IPO underpricing (IPORETN) against a number of proxies for ex ante uncertainty. That is, I test joint hypotheses that there is a positive relationship between risks and the degree of IPO underpricing and proxies used in the following regression are adequate measures of risks. IPORETNi = 0 + 1 1 1, 000, 000 + 2 EARNINGSi IPOVALUE i + 3 USAGEi + 4 INFORMEDi + 5 PROFSHAi + 6 LEVERAGEi + 7 ln AGEi + 8 MKTRUNUPi + 9 PREMSTDi + 10 STDi + 11 ln TIMEIPOi + 12 LDi + 13 EXDi + 14 TIMEi + k SIC(k)i + i (1)

1/IPOVALUE is the inverse of proceeds raised in an A-share IPO expressed in terms of 1993 purchasing power. It reects the maintained hypothesis that smaller offerings are more speculative, on average, than larger offerings (Beatty & Ritter, 1986). This implies that 1 is positive. In general, rms are unwilling to give out detailed information on what they will do with the net proceeds from IPOs because of increasing legal liability and exposure to competitors. However, the China Security Regulatory Committee (CSRC) requires highly speculative issues to provide future earnings forecasts and disclose IPO funds usage in their prospectus. To determine whether an issue is highly speculative, the CSRC set forth the following standards: (1) Over 10% of the sales revenue is outside the rms reported business scope, main operating region or relevant industry. (2) Over 30% of the sales revenue is with its headquarter or subsidiaries. (3) Fewer than three shareholders own more than 1% of the rms total shares. (4) The rms nancial statements are not audited, or the auditor has reservation about those statements. Falling into any of the above categories will automatically trigger the requirement of more stringent information disclosure. As a result of this regulation, issues that list

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

earnings forecasts and usage of IPO funds are associated with greater ex ante uncertainty.3 2 and 3 , the coefcients for EARNINGS and USAGE, should both be positive. The percentage of shares held by insiders and institutional investors (INFORMED), a proxy for the severity of the winners curse problem, is hypothesized to be positively related to underpricing. In addition, information on the past performance of a rm, such as calendar years prot prior to an IPO divided by the number of IPO shares (PROFSHA), debt-to-total assets ratio (LEVERAGE) and the age of the issuing rm (ln AGE), is related to the ex ante information asymmetry (Ritter, 1991; Su, 2003). In particular, the higher the past prot-per-share, the better is a rms growth potential. 5 should be negative. Su (2003) argues that a high pre-IPO leverage ratio raises ex ante uncertainty about the nancial strength of a rm, because debt nancing for investment projects is not a viable choice for imposing a hard budget constraint on management, while a small pre-IPO leverage conveys good news to the market. This suggests that 6 is positive. Ritter (1991) nds that there is a strong negative relationship between the age of the rm and the IPO initial return, which is consistent with the notion that risky issues require higher average returns and that age is an useful proxy for this risk. Therefore, 7 should be negative. Prevailing market conditions (MKTRUNUP and PREMSTD) inuence the assessment of rm risk. If market returns are high and the variance of returns is low at the time a rm goes public, the IPO initial return will naturally be high (Ritter, 1991). Moreover, risky rms have an incentive to go public when market conditions are favorable. Hence, 8 should be positive while 9 should be negative. Furthermore, Ritter (1984) uses the variability of stock returns of the issuing rm in the after-market period as one of the proxies for ex ante uncertainty. He nds signicant relationship between the variability of after-market returns and the degree of IPO underpricing for a sample of natural resource companies. He interprets his ndings as giving support to the claim that the greater the uncertainty about the true price of new shares, the larger is the discount that an issuer must offer in selling IPOs, and that there is no reason to restrict risk proxies to ex ante observable characteristics. Therefore, I hypothesize that the degree of IPO underpricing is positively related to STD, i.e., 10 is positive. Chowdhry and Sherman (1996) propose that IPO initial returns will be higher if the underwriter gets some direct compensation based on the size of the demand for IPO shares. In addition, when the offer price of an IPO is set many days before the actual issue day, there is a possibility that the rst-day price at which the issue would trade in the secondary market may leak to the public. It is well known that most Chinese A-share IPOs are sold through a lottery mechanism and the underwriter (typically a state bank) sells lottery application forms. The revenue from the sale of lottery forms belongs to the underwriter. The IPO price is also set long before shares are sold41 days on average. The empirical prediction is that the risk of an issue and hence, the degree of underpricing, will be higher if ln TIMEIPO is larger and/or a lottery mechanism is used in share allocation. This suggests that 11 is positive while 12 is negative. Since most rms listed in Shanghai are formerly large-scale state enterprises while most rms listed in Shenzhen are relatively small joint-venture companies, I add a variable EXD

3 For example, it is well known that Tsing Tao Brewery stated one use of its proceeds in the prospectus and then use the money for other purposes, which turned out to yield very disappointing returns to investors.

10

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

Table 6 Factors associated with IPO underpricing Factors Proceeds from the IPO Proportion of insider ownership Pre-IPO debt-to-assets ratio Protability Age of the rm Pre-issue market sentiment Post-issue stock variability Time elapsed for listing Disclosure dummy Stock exchange dummy Expected sign Negative Positive Positive Negative Negative Positive Positive Positive Positive Positive Rationale Smaller offerings are more speculative Adverse-selection problem is less severe when there are fewer informed investors Lower leverage may be considered as a sign of better future prospects Higher protability may be considered as a sign of better future prospects Well-established rms are better known and have less informational uncertainty Risky rms tend to go public during bullish markets The larger is return variability, the higher is the risk Issues with longer time for listing are more risky Firms required to disclose earnings forecast IPO fund usage are more risky Shanghai rms are of larger size, which in turn have less information asymmetry than Shenzhen

to capture the differential risks of these two types of rms. 13 is hypothesized to be positive. Finally, I use SIC(k) and TIME to control for industry-specic risks and risks associated with the year of IPOs.4 Table 6 summarizes factors associated with IPO underpricing and expected signs. I note that to raise a given amount of funds from IPO (IPOVALUE), a rm can sell a smaller fraction of ownership and thus, retain a larger fraction of shares held by government, managers, employees and other institutions (INFORMED). To detect possible simultaneous equation bias, I estimate regression (1) with and without 1/IPOVALUE for the entire sample of 587 rms and a sub-sample of 392 rms. All regressions are corrected for heteroskedasticity using the generalized least squares (GLS) procedure. I present regression results of initial-day underpricing on issue characteristics and proxies of informational uncertainty in Table 7. I nd that there are only minor differences among the regressions. The explanatory power of the model, as measured by the adjusted R2 , is between 0.58 and 0.67. The coefcient estimates for INFORMED are signicantly positive at the 5% level, indicating that IPO underpricing is smaller for issues in which the public knows a priori that government and other institutions have little or no participation. To further investigate the relationship between underpricing and the participation of insider and institutional investors, I rank rms in ascending order of INFORMED and group rms into quintiles. Table 8 compares IPO initial returns and some fundamental characteristics of rms that are grouped into the lowest and highest quintiles of INFORMED. As shown in the table, the mean IPO initial return is signicantly larger for the high INFORMED group than for the low INFORMED group. This suggests that the lemons problem is less pronounced in a market in which

4 Because rms going public in China typically use large state banks, which in turn use their branch networks, to distribute shares, there is little or no variation in underwriters reputation. I do not use variables such as investment banker prestige, venture capital backing and the use of warrants to underwriters as proxies for ex ante uncertainty.

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119 Table 7 GLS regression estimates for the relationship between IPO underpricing and proxies of uncertainty Full sample Constant 1,000,000/IPOVALUE EARNINGS USAGE INFORMED PROFSHA LEVERAGE ln AGE MKTRUNUP PREMSTD STD LD ln TIMEIPO EXD TIME SIC(1) SIC(2) Adjusted R2 4.862 (6.033) 0.801 (2.036) 1.368 (2.269) 2.117 (2.368) 0.522 (0.658) 0.893 (1.383) 1.627 (0.820) 4.126 (2.390) 2.068 (1.719) 0.596 (0.927) 1.250 (3.594) 0.822 (0.407) 1.692 (2.409) 8.207 (6.921) 2.851 (2.065) 3.350 (3.321) 0.582 5.590 (6.825) 8.202 (3.628) 0.872 (2.433) 1.055 (2.028) 1.950 (2.077) 0.868 (0.910) 1.401 (1.795) 1.935 (0.911) 5.288 (3.255) 1.584 (1.480) 0.825 (1.164) 0.986 (3.116) 0.645 (0.315) 1.308 (2.063) 8.926 (7.433) 3.260 (2.361) 3.091 (3.185) 0.605 Sub-sample 6.323 (7.380) 0.866 (2.319) 1.281 (2.195) 2.492 (2.615) 0.760 (0.782) 0.747 (1.304) 2.208 (1.026) 5.037 (3.071) 2.429 (1.901) 0.760 (1.084) 1.395 (3.720) 1.130 (0.624) 1.855 (2.640) 6.225 (5.826) 2.106 (1.744) 2.486 (2.654) 0.642

11

6.904 (8.119) 9.391 (4.188) 0.930 (2.680) 1.171 (2.110) 2.108 (2.294) 1.094 (0.994) 1.296 (1.716) 2.640 (1.185) 4.309 (2.312) 2.137 (1.788) 0.964 (1.237) 1.108 (3.204) 0.893 (0.447) 1.460 (2.488) 6.630 (6.009) 2.517 (1.920) 2.207 (2.513) 0.670

uninformed investors have prior knowledge of a lack of informed investors. This result is consistent with the winners curse hypothesis but is contradictory to the prediction of the signaling model of Perotti (1995), who argues that underpricing of state-enterprises IPOs is an equilibrium outcome for a government issuer to signal its future commitment to pro-market privatization policies. In Table 7, the coefcient estimates for EARNINGS and USAGE are both signicantly positive at the 5% level, suggesting that rms required to provide earnings forecasts and detailed usage of IPO proceeds experience higher IPO underpricing. The coefcient estimates for the reciprocal of the A-share proceeds from an IPO (1/IPOVALUE) are signicantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that smaller offerings have substantially higher average

Table 8 Comparison of the characteristics of rms grouped into the lowest and highest quintile of insider and institutional investors ownership Lowest quintile IPORETN INFORMED IPOVALUE LEVERAGE PROFSHA 2.59% 17.24% 65.18 0.31 0.25 Highest quintile 261.52% 64.3% 104.2 0.26 0.3 t-statistic of the difference 27.14 11.27 1.183 0.164 0.482

A comparison of some fundamental characteristics of rms grouped into the lowest and highest quintile of INFORMED, the percentage of shares held by insiders and institutional investors, based on the sample of 587 non-nancial rm-commitment domestic IPOs between January 1994 and December 1999. IPORETN is the degree of IPO underpricing, IPOVALUE is the offer price multiplied by the number of IPO shares in million US$, LEVERAGE is the pre-IPO debt-to-total assets ratio, and PROFSHA is the calendar years prot prior to the IPO divided by the total number of IPO shares. When calculating t-statistics of the differences in variables, the assumption of unequal variances between the two groups is used if the assumption of equal variance is rejected.

12

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

initial returns. The coefcient estimates for LEVERAGE are signicantly positive at the 10% level only when 1/IPOVALUE is included in the regression, providing weak evidence that investors perceive the debt-to-total assets ratio as a correlate with the ex ante uncertainty of the rm, and that the higher the pre-IPO leverage ratio, the larger is the expected initial return. However, neither ln AGE nor PROFSHA variable is related to underpricing, as the coefcient estimates for these two variables are not statistically signicant. Investors do not seem to view protability and rm age as relevant factors in IPO pricing. In addition, there is evidence that prevailing market conditions inuence the assessment of rm risk because the coefcient estimates for MKTRUNUP are signicantly positive at least at the 5% level and the coefcient estimates for PREMSTD are signicantly negative at the 10% level. Investors seem to believe that risky rms go public when market conditions are favorable (i.e., the pre-IPO market return is high while the standard deviation of returns is low) and require higher initial returns for risky rms. However, in contrast to empirical ndings of the US data by Ritter (1984), the variable STD is not only statistically insignicant, but also of wrong sign. Since I am testing joint hypotheses here, it is possible that the after-market standard deviation of returns is not a very good proxy for the ex ante uncertainty of the rm. Furthermore, I nd contradictory evidence from the Chinese data against Chowdhry and Sherman (1996) who propose that due to the possibility of information leakage, IPO underpricing will be higher if the offer price is set many days before the actual issue day. The coefcient estimates for ln TIMEIPO are insignicant at the conventional level, although it is of right sign. There is lack of evidence that the degree of IPO underpricing is related to the time elapsed between when the IPO price is set and when the issue is actually sold. An explanation is that over-subscription is unrelated to the time lag during issuing and listing. However, the coefcient estimates for LD are signicantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that underpricing is higher, on average, for rms that use a lottery mechanism in allocating shares. The coefcient estimates for EXD are signicantly positive, suggesting that rms listed in the Shenzhen Securities Exchange are, on average, more risky and have higher expected IPO underpricing. TIME, the variable representing the year of an IPO, is signicantly negative at the 1% level. This implies that rms going public in the early stages of development of Chinese stock markets were generally perceived as more risky rms, probably because the degree of information asymmetry among investors was larger at that time. The coefcient estimates for SIC1 and SIC2 are signicantly positive, indicating that durable and non-durable goods industries are underpriced more than the other industries, whose coefcient estimates are insignicant and hence, omitted from Table 7 for brevity. In summary, I nd evidence that there is a positive relation between proxies of ex ante uncertainty (primarily the percentage of insider and institutional investors ownership) and expected underpricing. My empirical results offer strong support for the winners curse hypothesis of IPO pricing.

4. The signaling models Allen and Faulhaber (1989), Grinblatt and Hwang (1989), and Welch (1989) have proposed a class of signaling models of IPO underpricing in which issuers have superior information than investors do about the intrinsic value of the rms. In their models, the

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

13

mean and variance of the companys future cash ows are unknown to investors; however, the offer price is used as a signal of unknown parameters. The issuer maximizes the value of the rm through the IPO and subsequent SEOs. In a separating equilibrium, a high-value issuer signals its quality by underpricing its IPO and retaining a portion of shares. It can afford to underprice its initial offering because it expects to capture larger revenues through after-market SEOs. In contrast, a low-value issuer does not signal because it does not expect to recoup its investment in underpricing through SEOs. The best a low-value issuer can do is to take the money and run when its stock is initially offered. When a separating equilibrium occurs, the average risk-adjusted IPO return over all new issues will be positive, the quantity of shares demanded for underpriced issues will exceed quantity supplied, and shares will be rationed by a mechanism other than the offer price. An empirical implication is that issuers with larger degree of IPO underpricing are more likely to return to the secondary market and offer larger amount of SEOs, more quickly than issuers with lower IPO underpricing. There are various stories rationalizing the signaling hypotheses. One linkage between the underpricing signal and SEO behavior is that an issuer gives out free samples to the public by underpricing and induces the public to learn more about the issuer. The learning process leads to a higher price on the rst day of market trading than would otherwise occurbut for high-value issuers only. This effect on the market price allows a high-value issuer to quickly return to the market with SEOs and thereby reap the return from underpricing its IPO. In another version, investors are more passive and learning occurs through exogenous revelation of information after implementation of the rms innovation. The IPO is underpriced to induce investors to furnish sufcient startup funds to enable implementation of the innovation. Firms are willing to underprice because they expect a higher-than-normal return on their investment. The alternative to a separating equilibrium is a pooling equilibrium where IPO prices are a weighted average of the present value of high-value and low-value issuers. When information is revealed after-market trading starts, price differentiation occurs, but the rst-day market price cannot be predicted from the IPO price and there is no risk-adjusted excess IPO initial return between the offer date and the rst-day market trading for a large sample of rms. In a pooling equilibrium, high-value rms do issue SEOs, but only in response to market-provided information about their value. That is, the market possesses superior information than the issuers. If the after-market returns are high, then rms will issue seasoned equities. If they are low, then there are no seasoned issues. No equilibrium signaling schedule exists. This is the so-called market-feedback hypothesis. Signaling models imply that high-quality issuers underprice their IPOs so that they can subsequently issue seasoned equities at more favorable prices than they would otherwise have received. Issuers that do not plan to sell seasoned equities subsequent to the IPOs do not discount their initial sales. In reality, not all IPOs that appear to be underpriced are followed by SEOs. Among the 392 rms going public before December 31, 1997, 375 of them are underpriced. Among the 375 underpriced rms, 309 of them have issued seasoned equities before December 31, 1999.5 As Jegadeesh et al. (1993) point out, some

5 About 80% of Chinese rms (318 out of 392 rms) going public before December 31, 1997 issued seasoned equities before December 31, 1999. About 97% of rms (309 out of 318 rms) issuing seasoned equities are underpriced.

14

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

of the rms that underprice their IPOs with the intention of issuing subsequent equities may fail to do so because of unexpected economic shocks. However, such shocks are less likely to prevent rms of very high quality to stick to their original plans. In addition, some underpricing may be unintentional or unexpected. Therefore, I view the relationship between IPO underpricing and subsequent offerings probabilistically, that (1) issuers with larger IPO underpricing are more likely to issue seasoned equities than issuers with lower expected IPO underpricing. Additional hypotheses related to IPO-SEO behavior are: (2) issuers with larger IPO underpricing will issue larger amounts of SEOs relative to their intrinsic value, and (3) issuers with larger IPO underpricing will issue SEOs more quickly after the initial sales. Empirical tests need to distinguish between the implications of a separating and a pooling equilibrium, where rms to do not signal their value to the investors through underpricing. A rms specic value is revealed only after-market trading begins. This suggests the market-feedback hypothesis, in which high post-IPO returns lead rms to issue seasoned equities and low post-IPO returns will discourage issues of additional shares. To test the hypothesis that issuers with larger expected IPO underpricing are more likely to issue SEOs, I estimate the following logit model, ln PiSEO 1 PiSEO = 0 + 1 IPORETNi + 2 AFTRETN1i + 3 AFTRETN2i (2)

where PiSEO is the probability that the ith issuer will issue SEOs after the initial sale. PiSEO = 1 if rm i issues seasoned equities, and 0 otherwise. The independent variables are the observed degree of IPO underpricing (IPORETN), the after-market return for the rst 2 weeks (AFTRETN1) and the after-market return for the third and fourth weeks (AFTRETN2).6 To correct for the possible error-in-variable (EIV) problem that arises from the use of the observed IPO initial returns, I obtain the IPO initial returns unexplained by ex ante uncertainties (IPORESID i ) as a proxy for underpricing. In particular, I rst obtain the tted value IPORETNi from regression (1) for each rm. I then subtract IPORETN i from IPORETN to get the value for IPORESIDi and use it in regression (2). The logit regression estimates are presented in Table 9. The slope coefcient for IPORETN and IPORETN i (t-statistics in parentheses) are 0.00171 (1.875) and 0.00286 (2.424), respectively, indicating a positive relationship between the degree of IPO underpricing and the probability for a rm to issue SEOs. To compare the explanatory power of the signaling versus market-feedback hypotheses, I calculate (P SEO /IPORETN) d(IPORETN), (P SEO /IPORESID ) d(IPORESID ) SEO and (P /AFTRETN1) d(AFTRETN1) and evaluate these three expressions using the standard deviation of the respective regressors, obtaining 1.3, 1.8, and 5.1, respectively, implying that a one standard deviation increase in after-market return over the rst 2 weeks

6 Jegadeesh et al. (1993) include a variable representing IPO size in their equation. Their rationale for including IPO size is Since rms that raise relatively small amounts of capital at the IPO may be more likely to return with a seasoned equity offering, I include the natural logarithm of IPO size as an additional explanatory variable. I believe that inclusion of IPO size as a regressor is inappropriate when the hypothesis being tested is that underpricing reduces the size of IPOs relative to SEOs. IPO size becomes endogenous and may well pick up the effect of underpricing I are trying to estimate.

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

15

Table 9 Logit regression estimates for the relationship among IPO underpricing, after-market returns and probability of SEOs Variable Constant IPORETN IPORESID AFTRETN1 AFTRETN2 [1] 1.638 (4.690) 0.00171 (1.875) [2] 2.073 (5.371) 0.00286 (2.424) 0.0295 (2.405) 0.0285 (1.261)

0.0407 (3.119) 0.0220 (1.137)

The dependent variable is the probability for the ith rm to issue SEOs, which takes value 1 if SEOs are observed and 0 otherwise. The independent variables are the observed IPO initial return (IPORETN) or the IPO initial return not explained by ex ante uncertainty (IPORESID), after-market rst 2-week return (AFTRETN1) and after-market next 2-week return (AFTRETN2). I allow two calendar years for a rm to issue SEOs, therefore My sample only consists of rms who went public between January 1994 and December 1997. There are 392 rms in the sample. Figures in parentheses are asymptotic t-statistics. Denotes 10% level of signicance. Denotes 5% level of signicance.

of market trading is associated with an increase in the magnitude of the probability of an SEO that is approximately four times larger than a one standard deviation increase in observed IPO return and more than three times larger than a one standard deviation increase in unexplained IPO return. Although the estimated coefcient for AFTRETN2 is much smaller, and not signicantly different from zero, the signicance and the explanatory power of AFTRETN1 lead us afrmatively to conclude that the empirical power of the market-feedback hypothesis is greater than that of the signaling hypothesis. To test the implication that rms with larger IPO underpricing tend to issue larger amount of seasoned equities, I estimate a Tobit regression that relates IPO underpricing and after-market returns to the ratio of a rms SEO value and its intrinsic value. The ratio is calculated by dividing the proceeds from all SEOs for an individual rm by the sum of the proceeds from its IPO and SEOs.7 The coefcient estimates of Eq. (3) are contained in Table 10. The coefcient estimate for IPORETN and IPORESID i (t-statistic) are 0.000224 (2.281) and 0.000350 (2.906), respectively, indicating that the higher the IPO underpricing, the larger is the size of seasoned equity issues. 0 + 1 IPORETNi + 2 AFTRETN1i SEOVALUE + 3 AFTRETN2i + i if RHS > 0 = (3) INTRINSC i 0 otherwise To compare the relative explanatory power of the signaling and market-feedback hypotheses, I follow the same procedure as with the estimates of Eq. (2) and calculate

7 I allow until December 31, 1999 for a rm to issue its rst SEO. About 80% of the rms that went public between January 1994 and December 1997 issued seasoned equity offerings before this date. Because My sample is censored as of the cutoff date of December 31, 1999, a rms true SEO behavior may not be observed within the stipulated time frame and a Tobit specication is desirable. For a more detailed econometric discussion on the censored regression and Tobit model, see Maddala (1983).

16

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

Table 10 Tobit regression estimates for the relationship among IPO underpricing, after-market returns and size of SEOs Variable Constant IPORETN IPORESID AFTRETN1 AFTRETN2 [1] 0.4868 (22.630) 0.000224 (2.281) [2] 0.343 (15.092) 0.000350 (2.906) 0.006925 (2.973) 0.000801 (1.116)

0.008447 (3.548) 0.000629 (1.240)

The dependent variable is the total amount of SEOs for rm i as a fraction of its intrinsic value (SEOVALUE/INTRINSC). The independent variables are the observed IPO initial return (IPORETN) or the IPO initial return not explained by ex ante uncertainty (IPORESID), after-market rst 2-week return (AFTRETN1) and after-market next 2-week return (AFTRETN2). I allow two calendar years for a rm to issue SEOs, therefore My sample only consists of rms who went public between January 1994 and December 1997. There are 392 rms in the sample. Figures in parentheses are asymptotic t-statistics. Denotes 10% level of signicance. Denotes 5% level of signicance.

[(SEOVALUE/INTRINSC)/IPORETN]d(IPORETN), [(SEOVALUE/INTRINSC)/ IPORESID] d(IPORESID ) and [(SEOVALUE/INTRINSC)/AFTRETN1] d(AFTRETN1) using the standard deviation of the respective regressors. I obtain 0.07, 0.11, and 0.19, indicating that a one standard deviation increase in observed IPO return, unexplained IPO return and rst 2-week after-market return are associated, respectively, with an increase in relative SEO size of 7%, 11%, and 19%, respectively. This comparison suggests that the market-feedback hypothesis has almost twice as much strength in explaining SEO relative magnitude than does the signaling hypothesis. As with the probability of an SEO, the coefcient estimate for AFTRETN2 is positive, but is statistically insignificant. I conclude that while the Tobit regression estimates support the signaling models relating observed and unexplained underpricing to the relative size of SEOs, they do not allow us to reject the alternative hypothesis. In fact, the size of SEOs is also strongly related to after-market returns. Finally, I examine the relationship between IPO underpricing and the time elapsed between the IPO and the rst SEO using the following Tobit model: TIMESEOi =

0 + 1 IPORETNi + 2 AFTRETN1i + 3 AFTRETN2i + i 0 if RHS > 0 otherwise

(4)

where TIMESEOi is the number of days elapsed between the IPO date and the rst SEO date for rm i. TIMESEOi = 0 if rm i has not offered any seasoned equities before December 31, 1999. The Tobit regression estimates are presented in Table 11. The slope coefcients (t-statistic) for IPORETN and IPORESID are 0.00082 (0.629) and 0.00218 (1.105), respectively, which I interpret as contradictory to the signaling hypothesis. However, the estimated coefcients for AFTRETN1 are signicantly negative at the 5% level, indicating that rms with larger after-market returns tend to issue SEOs more quickly than rms with lower after-market returns. Therefore, the Tobit analysis offers support for the market-feedback hypothesis. The main difference between my results and Su and Fleisher (1999)s is that my empirical ndings strongly support the market-feedback alternative rather than the signaling null.

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

17

Table 11 Tobit regression estimates for the relationship among IPO underpricing, after-market returns and time elapsed between IPO and rst SEO Variable Constant IPORETN IPORESID AFTRETN1 AFTRETN2 [1] 223.805 (24.626) 0.00082 (0.629) [2] 240.277 (28.530) 0.00218 (1.105) 0.2737 (3.443) 0.0921 (0.620)

0.1826 (2.950) 0.0785 (0.574)

The dependent variable is the number of days between the IPO date and the rst SEO date for the ith rm in the sample. The independent variables are the observed IPO initial return (IPORETN) or the IPO initial return not explained by ex ante uncertainty (IPORESID), after-market rst 2-week return (AFTRETN1) and after-market next 2-week return (AFTRETN2). I allow two calendar years for a rm to issue SEOs, therefore My sample only consists of rms who went public between January 1994 and December 1997. There are 392 rms in the sample. Figures in parentheses are asymptotic t-statistics. Denotes 5% level of signicance.

There are two possible explanations for this difference. One is that I use a more expanded dataset587 IPOs between January 1994 and December 1999 as opposed to 308 IPOs between January 1987 and December 1995. The exclusion of early data and inclusion of more recent data in this paper avoids institutional peculiarities associated with early development of capital markets and provide better scrutinization of rms behavior in a more market-oriented new issues process. Another is that I use different approach in formulating regressions (2)(4). Besides using the raw IPO initial return IPORETM, I use the under pricing residual IPORESID as an explanatory variable. IPORESID captures the IPO initial return unexplained by ex ante uncertainty and as the results in this section clearly show, provides better t to the model.

5. Conclusion The pricing and valuation of new issue companies have received a lot of interest in the academic community. Many theoretical models have been developed to explain how entrepreneurs can convey their private knowledge about the IPO to potential investors. Models explaining the widespread occurrence of underpricing have been derived and tested. Some of these models relate IPO underpricing to ex ante uncertainties surrounding an issue, while others examine the signaling role of underpricing. There have been a number of empirical studies based on US data and data from other developed and emerging markets, but the evidence in support of the theory has been mixed. In this paper, I empirically investigate winners curse and signaling models using Chinese data. The Chinese IPO market is of interest because it is distinct from other market economies in its economic conditions and institutional framework. Because of the high economic uncertainty inherent in the privatization process, stock markets in China are characterized by large information asymmetry. Chinese corporate and securities laws are less structured and contain more loopholes than those in the US. Laws pertaining investor protection are not known to be rigorously enforced. This suggests that adverse-selection problem may be quite

18

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

serious for companies going public. Another unique feature is that many companies have varying levels of government ownership in the form of state shares or legal entity shares. The high percentage of equity retention by insiders suggests that underpricing signal may differ signicantly from that in the US and other countries. This empirical work is consistent with these views. Major ndings in support of the winners curse and signaling models include: (1) The degree of IPO underpricing is correlated with proxies of ex ante uncertainties surrounding a new issue, including the size of offerings, insider ownership, disclosure practice, market conditions, allocation mechanism, listing exchange and listing year. (2) IPO initial return is negatively related to the size of offerings and positively related to insider ownership of shares. The adverse-selection problem is less pronounced in a market in which uninformed investors have prior knowledge of a lack of informed investors. (3) IPO initial return is positively related to the stock-market risk. Firms required to provide earnings forecasts and usage of IPO proceeds experience higher IPO underpricing. When a lottery mechanism is used in allocating shares, underpricing is signicantly higher. (4) There is evidence from the observed IPO initial returns and underpricing residuals that rms which underprice more are more likely to issue larger amount of seasoned equities, but not more quickly than rms which underprice less. Although empirical results generated from the Chinese data are largely consistent with adverse-selection and signaling hypotheses, there exists strong evidence in support of the market-feedback hypothesis. Firms that experience higher after-market returns during the rst 2 weeks of trading are more likely to issue larger amount of seasoned equities more quickly. Further analysis indicates that the market-feedback hypothesis has more empirical power than the signaling hypothesis.

Acknowledgments I thank Kenneth Kopecky, Executive Editor, Ravi Shukla, Editor, an anonymous referee, John Afeck-Graves, Lisa Bruno, Mike Levis, Jun Liu, Qing Ma, Neil Stevens, Hongzhi Zhou and seminar participants at Jinan University and International Conference Problems and Progress in Chinas Financial Reform for their helpful comments and suggestions. I also acknowledge nancial support by the Scientic Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry.

References

Afeck-Graves, J., Hegde, S., & Miller, R. (1996). Conditional price trends in the aftermarket for initial public offerings. Financial Management, 25, 2540. Aggarwal, R., Leal, R., & Hernandez, F. (1993). The aftermarket performance of initial public offerings in Latin America. Financial Management, 22, 4253. Allen, F., & Faulhaber, G. (1989). Signaling by underpricing in the IPO market. Journal of Financial Economics, 23, 303323.

D. Su / Journal of Economics and Business 56 (2004) 119

19

Beatty, R., & Ritter, J. (1986). Investment banking, reputation, and the underpricing of initial public offerings. Journal of Financial Economics, 15, 213232. Chowdhry, B., & Sherman, A. (1996). International differences in over-subscription and underpricing of IPOs. Journal of Corporate Finance, 2, 359381. Clarkson, P., & Merkley, J. (1994). Ex ante uncertainty and the underpricing of initial public offering: Further Canadian evidence. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 11, 5467. Firth, M. (1997). An analysis of the stock market performance of new issues in New Zealand. Pacic-Basin Finance Journal, 5, 6385. Garnkel, J. (1993). IPO underpricing, insider selling and subsequent equity offerings: Is underpricing a signal of quality? Financial Management, 22, 7483. Grinblatt, M., & Hwang, C. (1989). Signaling and the pricing of unseasoned new issue. Journal of Finance, 44, 393420. Jegadeesh, N., Weinstein, M., & Welch, I. (1993). An empirical investigation of IPO returns and subsequent equity offerings. Journal of Financial Economics, 34, 153175. Keloharju, M. (1993). The winners curse, legal liability, and the long run price performance of initial offerings in Finland. Journal of Financial Economics, 34, 251277. Kim, J., Krinsky, I., & Lee, J. (1995). The aftermarket performance of initial public offerings in Korea. Pacic-Basin Finance Journal, 3, 429448. Koh, F., & Walter, T. (1989). A direct test of Rocks model of the pricing of unseasoned issues. Journal of Financial Economics, 23, 251271. Lee, P., Taylor, S., & Walter, T. (1996). Australian IPO pricing in the short and long run. Journal of Banking and Finance, 20, 11891210. Levis, M. (1993). The long-run performance of initial public offerings: The UK experience 19801988. Financial Management, 22, 2841. Ljungqvist, A. (1997). Pricing initial public offerings: Further evidence from Germany. European Economic Review, 41, 13091320. Loughran, T., Ritter, J., & Rydquist, K. (1994). Initial public offerings: International insights. Pacic-Basin Finance Journal, 2, 165199. Maddala, G. (1983). Limited dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics. New York: Cambridge University Press. Michaely, R., & Shaw, W. (1994). The pricing of initial public offerings: Tests of adverse selection and signaling theories. Review of Financial Studies, 7, 279319. Paudyal, K., Saadouni, B., & Briston, R. (1998). Privatization initial public offerings in Malaysia: Initial premium and long-term performance. Pacic-Basin Finance Journal, 6, 427451. Perotti, E. (1995). Credible privatization. American Economic Review, 85, 847859. Ritter, J. (1984). The hot issue market of 1980. Journal of Business, 57, 215240. Ritter, J. (1991). The long-run performance of initial public offerings. Journal of Finance, 43, 789822. Rock, K. (1986). Why new issues are underpriced? Journal of Financial Economics, 15, 187212. Su, D. (2003). Chinese stock markets: A research handbook. Singapore: World Scientic Publishing (UK) Ltd. Su, D., & Fleisher, B. (1999). An empirical investigation of underpricing in Chinese IPOs. Pacic-Basin Finance Journal, 7, 173202. Welch, I. (1989). Seasoned offerings, imitation costs and the underpricing of initial public offerings. Journal of Finance, 44, 421449.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Activity 2 Example 1.2 PunzalanHarseyJoyDocumento14 pagineActivity 2 Example 1.2 PunzalanHarseyJoyHarsey Joy PunzalanNessuna valutazione finora

- 01 - Mango Financial Management Essentials (232p)Documento232 pagine01 - Mango Financial Management Essentials (232p)Book File100% (6)

- Project On IPODocumento105 pagineProject On IPOArvind MahandhwalNessuna valutazione finora

- ECF Group16Documento26 pagineECF Group16Priyank ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- What Drives Differences in UnderpricingDocumento23 pagineWhat Drives Differences in Underpricinggogayin869Nessuna valutazione finora

- Philip J. Lee-1999Documento21 paginePhilip J. Lee-1999EndiNugrohoNessuna valutazione finora

- Research PaperDocumento18 pagineResearch Paperapi-317623686Nessuna valutazione finora

- Overnight Returns & Intraday Returns. Are They Correlated?Documento6 pagineOvernight Returns & Intraday Returns. Are They Correlated?av_meshramNessuna valutazione finora

- Time-VaryingDemandForLottery Specul - Preview PDFDocumento54 pagineTime-VaryingDemandForLottery Specul - Preview PDFebiz hackerNessuna valutazione finora

- TOPIC 4 StudyDocumento12 pagineTOPIC 4 StudyaccaafmvideosNessuna valutazione finora

- Volatility SkewDocumento43 pagineVolatility SkewjustNeoNessuna valutazione finora

- Session2 - 02 - The Efficiency of IPO StocksDocumento86 pagineSession2 - 02 - The Efficiency of IPO Stocksddi40275Nessuna valutazione finora

- LR Insider TradingDocumento4 pagineLR Insider TradingAsif Khan NiaziNessuna valutazione finora

- Anchor Investors in IPOs PDFDocumento45 pagineAnchor Investors in IPOs PDFShesharaNessuna valutazione finora

- Goldstein, Guembel ('08) - ManipulationDocumento32 pagineGoldstein, Guembel ('08) - Manipulationmert0723Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unchecked Intermediaries by Khawaja & MianDocumento15 pagineUnchecked Intermediaries by Khawaja & Mianmuneebmateen01Nessuna valutazione finora

- IPO Chinese StyleDocumento72 pagineIPO Chinese StyleAriSBNessuna valutazione finora

- Do Behavioral Biases Affect Prices?: Joshua D. Coval and Tyler ShumwayDocumento34 pagineDo Behavioral Biases Affect Prices?: Joshua D. Coval and Tyler Shumwaysafa haddadNessuna valutazione finora

- Research ReportDocumento17 pagineResearch Reportapi-317623686Nessuna valutazione finora

- LR 10 ReportsDocumento10 pagineLR 10 ReportsHari PriyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Insider Sentiment and Market Returns Around The World: Fbrochet@mit - EduDocumento55 pagineInsider Sentiment and Market Returns Around The World: Fbrochet@mit - EduLiew Chee KiongNessuna valutazione finora

- The Determinants of Informed Trading: Implications For Asset PricingDocumento51 pagineThe Determinants of Informed Trading: Implications For Asset PricingHsuan YangNessuna valutazione finora

- Review of LiteratureDocumento4 pagineReview of LiteratureYogeshWarNessuna valutazione finora

- Sujan Karki - Literature ReviewDocumento30 pagineSujan Karki - Literature ReviewsujankarkieNessuna valutazione finora

- IpoDocumento53 pagineIponguyenkhoa86Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Effect of Round Number Bias in U.S. and Chinese Stock MarketsDocumento38 pagineThe Effect of Round Number Bias in U.S. and Chinese Stock MarketsEric GuoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Predictive Nature of Financial Ratios: Adam TurkDocumento9 pagineThe Predictive Nature of Financial Ratios: Adam TurkShaguftaNessuna valutazione finora

- Overconfidence Among Option Traders: Han-Sheng Chen Sanjiv SabherwalDocumento31 pagineOverconfidence Among Option Traders: Han-Sheng Chen Sanjiv SabherwalRenata Pires de SouzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Volume 2Documento38 pagineVolume 2zhusatrianiNessuna valutazione finora

- Ipo Market TimingDocumento34 pagineIpo Market TimingZulfikar FuadNessuna valutazione finora

- Brown and Cliff (2004)Documento27 pagineBrown and Cliff (2004)Ciornei OanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect AuditsDocumento5 pagineEffect Auditsindri retnoningtyasNessuna valutazione finora

- IDocumento7 pagineIHezekia KiruiNessuna valutazione finora

- Nber Working Paper SeriesDocumento43 pagineNber Working Paper SeriesSiddharth AnandNessuna valutazione finora

- Underpricing of Initial Public OfferingsDocumento18 pagineUnderpricing of Initial Public Offeringsgogayin869Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ipo 1Documento44 pagineIpo 1aamritaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Haugen BakerDocumento39 pagineHaugen Bakerjared46Nessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting Information and Stock Price Reaction of Listed Companies - Empirical Evidence From 60 Listed Companies in Shanghai Stock ExchangeDocumento11 pagineAccounting Information and Stock Price Reaction of Listed Companies - Empirical Evidence From 60 Listed Companies in Shanghai Stock ExchangeAnonymous n9DGmLYKNessuna valutazione finora

- IporeturnsandfactorsDocumento22 pagineIporeturnsandfactorsKaun Hai ThumNessuna valutazione finora

- Foreign Exchange SpeculationDocumento13 pagineForeign Exchange SpeculationKristy Dela PeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Project On IPO of Cafe Coffee DayDocumento45 pagineProject On IPO of Cafe Coffee DayVinit Dawane100% (1)

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocumento3 pagineEfficient Market HypothesisShameem AnwarNessuna valutazione finora

- Short Selling, Informational Efficiency, and Extreme Stock Price Adjustment China BasedDocumento20 pagineShort Selling, Informational Efficiency, and Extreme Stock Price Adjustment China BasedAbhishree JainNessuna valutazione finora

- An Empirical Examination of The Pricing of Seasoned Equity OfferingsDocumento17 pagineAn Empirical Examination of The Pricing of Seasoned Equity OfferingsAhmad Ismail HamdaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Earnings and Cash Flow Performances Surrounding IpoDocumento20 pagineEarnings and Cash Flow Performances Surrounding IpoRizki AmeliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Glaser and Weber 2009 Which Past Returns Affect T-WT - SummariesDocumento5 pagineGlaser and Weber 2009 Which Past Returns Affect T-WT - SummariesMohamed SabryNessuna valutazione finora

- The Variability of IPO Initial Returns: Michelle Lowry, Micah S. Officer, and G. William SchwertDocumento42 pagineThe Variability of IPO Initial Returns: Michelle Lowry, Micah S. Officer, and G. William SchwertAhmadi AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Unchecked Intermediaries:price Manipulation in An Emerging Stock MarketDocumento39 pagineUnchecked Intermediaries:price Manipulation in An Emerging Stock MarketMan Ho LiNessuna valutazione finora

- Sharma Seraphim Je38Documento29 pagineSharma Seraphim Je38Irisha AnandNessuna valutazione finora

- Theory of Ipo WavesDocumento39 pagineTheory of Ipo WavesVanyaa KansalNessuna valutazione finora

- Investment Behaviour of Analysts: A Case Study of Pakistan Stock ExchangeDocumento18 pagineInvestment Behaviour of Analysts: A Case Study of Pakistan Stock Exchangesajid bhattiNessuna valutazione finora

- Stock Market and Investment-DikonversiDocumento59 pagineStock Market and Investment-DikonversiAkbar 1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Choi - JOBF - 2015 - Institutional Herding in International MarketsDocumento14 pagineChoi - JOBF - 2015 - Institutional Herding in International MarketsGouri Sankar SahooNessuna valutazione finora

- Financing and Signaling Decisions Under Asymmetric Information - An Experimental StudyDocumento26 pagineFinancing and Signaling Decisions Under Asymmetric Information - An Experimental StudyWihelmina DeaNessuna valutazione finora

- Does Disclosure Regulation Work? Evidence From International IPO MarketsDocumento65 pagineDoes Disclosure Regulation Work? Evidence From International IPO MarketschethansoNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Governance and IPO Underpricing: Evidence From The Italian MarketDocumento39 pagineCorporate Governance and IPO Underpricing: Evidence From The Italian MarketminnvalNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Do Option Prices Predict Stock ReturnsDocumento49 pagineWhy Do Option Prices Predict Stock ReturnsSanket Patel100% (1)

- Introduction (Muhammad Amin - 1735237)Documento7 pagineIntroduction (Muhammad Amin - 1735237)Amin H. HamdaniNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study of Ipo Project RepotDocumento13 pagineA Study of Ipo Project RepotKurapati VenkatkrishnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Stock Market Volatility Research PaperDocumento6 pagineStock Market Volatility Research Paperefj02jba100% (1)

- Event Study Using Anfis (A Neural Model) : Predicting The Impact of Anticipatory Action On Us Stock Market - AN FuzzyDocumento8 pagineEvent Study Using Anfis (A Neural Model) : Predicting The Impact of Anticipatory Action On Us Stock Market - AN FuzzyJose GueraNessuna valutazione finora

- Applied Economic Analysis of Information and RiskDa EverandApplied Economic Analysis of Information and RiskMoriki HosoeNessuna valutazione finora

- Rug01-002164545 2014 0001 Ac PDFDocumento85 pagineRug01-002164545 2014 0001 Ac PDFSehrish KayaniNessuna valutazione finora

- NEW Jobs 2011Documento1 paginaNEW Jobs 2011Sehrish KayaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction and Growth FactsDocumento14 pagineIntroduction and Growth FactsSehrish KayaniNessuna valutazione finora

- 04-Fiscal Development 09Documento18 pagine04-Fiscal Development 09Sehrish KayaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Macroeconomics Variables On Stock Prices: Emperical Evidance in Case of Kse (Karachi Stock Exchange)Documento8 pagineImpact of Macroeconomics Variables On Stock Prices: Emperical Evidance in Case of Kse (Karachi Stock Exchange)Sehrish KayaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Vivian ChepkemboiDocumento8 pagineVivian ChepkemboiBolt essays100% (1)

- Disturbing Questions: INCOME PROTECTION: Ideal For Young Couples Starting Up A FamilyDocumento7 pagineDisturbing Questions: INCOME PROTECTION: Ideal For Young Couples Starting Up A FamilyCherryber UrdanetaNessuna valutazione finora

- FINANCIAL REPORTING II .... Anthony EduahDocumento294 pagineFINANCIAL REPORTING II .... Anthony EduahAnita SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- Practice Exercise 11-28-22Documento82 paginePractice Exercise 11-28-22崔梦炎Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ipos, Their Pros, Cons, and The Ipo Process: GlossaryDocumento6 pagineIpos, Their Pros, Cons, and The Ipo Process: GlossaryMESRETNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is The MUR (Mauritius Rupee) ?Documento3 pagineWhat Is The MUR (Mauritius Rupee) ?Jonhmark AniñonNessuna valutazione finora

- Objective Review of Literature Research Methodology Limitations To Research Introduction To BankingDocumento54 pagineObjective Review of Literature Research Methodology Limitations To Research Introduction To BankingLakshyay RawatNessuna valutazione finora

- Sekai WaDocumento2 pagineSekai WaMicaela EncinasNessuna valutazione finora

- International Business: Seventeenth Edition, Global EditionDocumento12 pagineInternational Business: Seventeenth Edition, Global EditionAhmad Khaled DahnounNessuna valutazione finora

- P 16-3 PDFDocumento2 pagineP 16-3 PDFNatasha PNessuna valutazione finora

- DD309Documento23 pagineDD309James CookeNessuna valutazione finora

- Maf603 Test 1 Oct 2020 - SolutionDocumento3 pagineMaf603 Test 1 Oct 2020 - SolutionSITI FATIMAH AZ-ZAHRA ABD WAHIDNessuna valutazione finora

- CitizenM Hotel InnovationDocumento9 pagineCitizenM Hotel InnovationDydda 7Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sample of Doctoral Thesis On Corporate Governance and Financial PerformanceDocumento5 pagineSample of Doctoral Thesis On Corporate Governance and Financial Performancexgkeiiygg100% (2)

- 34 - Neha Sabharwal - Panacea BiotechDocumento10 pagine34 - Neha Sabharwal - Panacea Biotechrajat_singlaNessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting ExampleDocumento19 pagineAccounting ExampleKevin GalindoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 4 Sources of IncomeDocumento9 pagineLesson 4 Sources of IncomeErick MeguisoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 Accounting For Budgetary AccountsDocumento33 pagineChapter 2 Accounting For Budgetary AccountsRia BagoNessuna valutazione finora

- Brunello Cucinelli Case StudyDocumento16 pagineBrunello Cucinelli Case StudyJASPREET KAURNessuna valutazione finora

- PartnershipDocumento49 paginePartnership20230773Nessuna valutazione finora

- Balance Sheet PosterDocumento2 pagineBalance Sheet PosterVeronika RaichevaNessuna valutazione finora

- Radio One - For ClassDocumento26 pagineRadio One - For ClassRicha ChauhanNessuna valutazione finora

- APC Partner Direct Team CLA Contest For Jun'23Documento17 pagineAPC Partner Direct Team CLA Contest For Jun'23menakaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1 - Examining Business & EconomicsDocumento12 pagineChapter 1 - Examining Business & EconomicsAdam HendersonNessuna valutazione finora

- Rating MethodologiesDocumento42 pagineRating MethodologiesSamNessuna valutazione finora

- My WorkDocumento47 pagineMy Workmuzo213Nessuna valutazione finora

- B2B MarketingDocumento17 pagineB2B Marketingvc8446526703Nessuna valutazione finora

- Team-1 Module 2 Practice-ProblemsDocumento10 pagineTeam-1 Module 2 Practice-ProblemsMay May MagluyanNessuna valutazione finora