Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Consumer Attitude Towards Counterfeits

Caricato da

kanwalasgharDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Consumer Attitude Towards Counterfeits

Caricato da

kanwalasgharCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits: a review and extension

Celso Augusto de Matos

Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (PPGA-EA-UFRGS), Brazil

Cristiana Trindade Ituassu

Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil, and

Carlos Alberto Vargas Rossi

Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (PPGA-EA-UFRGS), Brazil

Abstract Purpose The purpose of this research is to propose and test a model that integrates the main predictors of consumers attitude and behavioral intentions toward counterfeits; to help companies understand the main factors inuencing consumer behavior toward counterfeits and create effective anti-piracy strategies. Design/methodology/approach An integrated model is proposed following the studies by Ang et al. and Huang et al. A survey with 400 consumers was conducted in the Brazilian market and the Structural Equation Modeling technique was used to test the hypothesized relationships. Findings The main contribution of the paper is to show that consumer intentions to buy counterfeited products are dependent on the attitudes they have toward counterfeits, which in turn are more inuenced by perceived risk, whether consumers have bought a counterfeit before, subjective norm, integrity, price-quality inference and personal gratication. The paper reinforces the mediator role of attitude in the relationship between these antecedents and behavioral intentions. Moreover, previous experience with counterfeits consumption does not have a direct effect on behavioral intentions, but only an indirect effect through attitude. Practical implications The paper contributes to inform policy makers and managers of brands about the main predictors of consumers attitudes toward counterfeits. In this way, ads intended to discourage consumption of counterfeits could use the perceived risk as the main message appeal. Originality/value This paper investigates the key antecedents and consequences of consumer attitudes toward counterfeits by integrating and testing two recent models dealing with this subject in the marketing literature. Keywords Attitudes, Consumer behaviour, Counterfeiting, Risk assessment, Brazil Paper type Research paper

An executive summary for managers and executive readers can be found at the end of this article.

Introduction

Counterfeiting is a signicant and growing problem worldwide, occurring both in less and well developed countries. In the USA economy, the cost of counterfeiting is estimated to be up to $200 billion per year (Chaudhry et al., 2005). Considering the countries worldwide, almost 5 percent of all products are counterfeit, according to the International Anticounterfeiting Coalition (IACC, 2005) and the International Intellectual Property Institute (IIPI, 2003). A number of denitions have been used for product counterfeiting. In this paper, we use the one given by Cordell et al. (1996) and also used by Chaudhry et al. (2005): any unauthorized manufacturing of goods whose special characteristics are protected as intellectual property rights

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0736-3761.htm

(trademarks, patents and copyrights) constitutes product counterfeiting. Actions to limit counterfeits can arise from both supply and demand side, considering the tactics companies employ to deter counterfeits (Chaudhry et al., 2005) and the motivations that make a counterfeit an interesting option for some customers (Huang et al., 2004; Ang et al., 2001). Because research addressing counterfeit purchasing from the consumers perspective is still incipient, especially considering the antecedents of the construct attitudes toward counterfeits, this study focuses on the demand side. The aim is to propose and to test a model that deals with the main predictors of consumer attitudes toward counterfeits and their intentions to buy such products, integrating the main ndings existing in the literature. The article is presented in ve parts. First, a brief review of the main antecedents and consequences of the consumer attitudes toward counterfeits were examined, resulting in a conceptual model to be tested. Second, valid scales for the constructs considered in the model were identied in the literature. Third, the conceptual model was tested by means of the structural equation modeling. Fourth, a discussion of the main results is presented, comparing ndings with

The authors are thankful for the support provided by the Brazilian Funding Council for Research (Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa CNPq.)

Journal of Consumer Marketing 24/1 (2007) 36 47 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited [ISSN 0736-3761] [DOI 10.1108/07363760710720975]

36

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

previous studies. Finally, the conclusions are presented, including the main contribution of the study and strategies managers can use in order to reduce consumer attitudes toward counterfeits.

Theoretical background and conceptual model

Consumer attitude toward counterfeits Attitude is . . .a learned predisposition to behave in a consistently favorable or unfavorable manner with respect to a given object (Schiffman and Kanuk, 1997, p. 167). Indeed, according to Bagozzi et al. (2002, p. 4), the most widely accepted denition of attitude conceives of it as an evaluation, for example: . . .a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor. (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993, p. 1). Attitude is considered to be highly correlated with ones intentions, which in turn is a reasonable predictor of behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). In these authors rationale (i.e. theory of reasoned action), not only the attitude one has toward an object will affect his/her intentions toward it, but also what inuences one receives from his/her reference group will be important, namely the subjective norms. In summary, intentions to perform a behavior will be inuenced by individual and interpersonal level factors. In the context of this study, consumer evaluation of counterfeits will be an important predictor of his/her intention to buy a counterfeit, as well as how much agreement about this behavior he/she receives from his/her reference group. In this way, what factors inuence consumer evaluation of a counterfeit becomes the focus of the investigation. Based on the literature review, the main predictors are presented below. Price quality inference As the two main differences consumers perceive between a counterfeit and an original product are the lower prices and the poorer guaranties, price and risk constructs are likely to be important factors related to attitude toward counterfeits (Huang et al., 2004). In fact, previous studies have shown that price difference is an important variable when choosing a counterfeit (Cespedes et al., 1988; Cordell et al., 1996). Inference of quality by the price level is a common belief among consumers and an important factor in consumer behavior (Chapman and Wahlers, 1999). In this sense, consumers tendency to believe that high (low) price means high (low) quality becomes even more important when there is little information about the product quality or the consumer is unable to judge product quality (Tellis and Gaeth, 1990). As proposed also by Huang et al. (2004), considering that counterfeits are usually sold at lower prices, the greater the relationship price-quality for the consumer, the lower his/her perception of quality for the counterfeits. For this reason, it is expected that: H1. A consumer who more strongly believes in the pricequality inference has a more negative attitude toward counterfeits. Risk averseness and perceived risk in counterfeits purchasing Risk averseness is dened as the propensity to avoid taking risks and is generally considered a personality variable (Bonoma and Johnston, 1979; Zinkhan and Karande, 1990). This psychological consumer trait is an important characteristic for discriminating between buyers and nonbuyers of a product category, especially a risky one (e.g. 37

Internet shoppers and non-shoppers, Donthu and Garcia, 1999). In the context of counterfeits, Huang et al. (2004) found a signicant inverse relationship between risk averseness and attitude. Following these authors rationale, we expected that: H2. Consumers who are more (less) risk averse will have unfavorable (favorable) attitude toward counterfeits. As stated in H2, consumers believe that counterfeits are sold with lower prices and poorer guaranties. Because of this, the risk variable is as important as the price-quality inference. The concept of perceived risk more often used in marketing literature denes risk in terms of the consumers perceptions of the uncertainty and adverse consequences of buying a product or service (Dowling and Staelin, 1994). Hence, consumers judge what are the chances that a problem might occur and also what will be the negative consequences of such problem, and this judgment will inuence every stage of the consumer decision-making process. As the nature of these problems vary, the risk might include different components, such as performance, nancial, safety, social, psychological, and time/opportunity dimensions (Havlena and DeSarbo, 1991). Albers-Miller (1999) found a signicant role of the risk factor on the purchasing of counterfeits. In this context, a consumer may consider that: . the product will not perform as well as an original item and there will be no warranty from the seller; . choosing a counterfeit will not bring the best possible monetary gain; . the product may not be as safe the original one . the selection of a counterfeit will affect in a negative way how others perceive them; and . he/she will waste time, lose convenience or waste effort in having to repeat a purchase. In this sense, it is hypothesized that: H3. Consumers who perceive more (less) risk in counterfeits will have unfavorable (favorable) attitude toward counterfeits.

Integrity Consumer purchase of a counterfeit is not a criminal act, but as consumer participation in a counterfeit transaction supports illegal activity (i.e. counterfeit selling), consumers respect for lawfulness might explain how much engagement he/she will have in buying counterfeits. Indeed, research shows that consumers willingness to purchase counterfeit products is negatively related to attitudes toward lawfulness (Cordell et al., 1996). In this sense, those consumers who have lower ethical standards are expected to feel less guilty when buying a counterfeit (Ang et al., 2001). Rather, they rationalize their behavior in a way to reduce the cognitive dissonance of an unethical behavior. Using this rationale, we expect that: H4. Consumers who attribute more (less) integrity to themselves will have unfavorable (favorable) attitude toward counterfeits. Personal gratication Personal gratication concerns the need for a sense of accomplishment, social recognition, and to enjoy the ner things in life (Ang et al., 2001). There are conicting results in this aspect in the literature because Bloch et al. (1993) suggest

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

that consumers choosing a counterfeit see themselves as less well off nancially, less condent, less successful and lower status than counterfeit non-buyers; on the other hand, result found by Ang et al. (2001) showed no signicant inuence of personal gratication on consumer attitudes toward counterfeits. Because of this, we do not hypothesize the direction of the relationship, but only that: H5. Consumers sense of accomplishment will affect their attitude toward counterfeits. Subjective norm Subjective norm is a social factor referring to the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform a given behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Consumers may be informationally susceptible, when expertise from others inuences their choice (e.g. when one does not know the product category), and also normatively susceptible, when they are more interested in making a good impression to others (Bearden et al., 1989). Regarding counterfeits, friends and relatives may act as inhibitors or contributors to the consumption, depending on how much this behavior is approved by them. Hence, it is expected that: H6. Consumers perceiving that their friends/relatives approve (do not approve) their behavior of buying a counterfeit will have favorable (unfavorable) attitude toward counterfeits. Previous experience Research has shown that counterfeits buyers are different from non-buyers, with the former viewing such purchases as less risky, trusting stores that sell counterfeits and not viewing this purchase as unethical (Ang et al., 2001). Hence in this study, it is expected that: H7A. Consumers who have already bought (have never bought) a counterfeit have more favorable (unfavorable) attitude toward counterfeits. H7B. Consumers who have already bought (have never bought) a counterfeit have more favorable (unfavorable) behavioral intentions toward counterfeits.

Method

A survey was conducted among consumers in two big Brazilian cities. They were interviewed in the streets close to the points where counterfeited products were being sold. Interviewers were trained by the authors in administrating the survey instrument and were instructed to include in the sample people with different prole, considering age, gender, education and income. A question concerning whether participant had already bought a counterfeited product was also included in the instrument. Data collection was performed both on week and weekend days. A total of 400 individuals answered the survey instrument and were used in the data analysis. Based on the literature, the authors built the survey instrument, using scales that were already validated in previous research. Table I summarizes the items used for each construct, as well as the authors used as reference. Participants answered these items using Likert scales varying from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). Only the scale of behavioral intentions used a different format, with anchors varying from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely). In this study it was not specied any counterfeited product in particular. Questions considered the expression counterfeited products in general because the aim at this moment was to assess consumer attitudes toward counterfeited products overall. After data collection, the analysis followed these steps: . descriptive statistics for the scale items and for the demographic variables; . missing values and outliers detection; . linearity between the scale items; . dimensionality using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA); . reliability and validity of the scale items using internal consistency coefcient (Cronbachs alpha), as well as composite reliability and average variance extracted as suggested in the measurement literature (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Gerbing and Anderson, 1988); and . estimation of model parameters and interpretation.

Results

Descriptive analysis The following prole was found among the participants: 230 (57.6 percent) were female, 74 (18.5 percent) were 20 years old or less, 86 (21.5 percent) were between 21 and 25 years, 47 (11.8 percent) between 26 and 30 years, 86 (21.6 percent) were between 30 and 40 years and 106 (26.6 percent) had 41 years or more. In terms of education, 208 (52 percent) had already completed high school, followed by those who had not, 120 (30 percent). Concerning personal income, the majority (171 or 43 percent) said they received monthly up to R$500.00 (equivalent to US$230.00), followed by 149 (37 percent) in the range between R$500.00 and R$1,000 (149 or 37 percent) and 79 (20 percent) with more than R$1,000 by month. Most of the participants (279 or 70 percent) afrmed that they had already bought a counterfeit. The scale items presented means varying from 2.15 (item I like shopping for gray market goods) to 6.88 (item I admire responsible people). In general, the scale means indicate that respondents manifested unfavorable attitudes toward counterfeited products and low behavioral intentions toward them. 38

Behavioral Intentions

The link attitude-behavioral intentions has been extensively examined in the marketing literature. According to the Theory of Reasoned Action, attitude is positively correlated with behavioral intentions, which in turn is an antecedent of the real behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). Indeed, research has found support on this relationship (Kim and Hunter, 1993). In the context of counterfeits, it is expected that: H8: Consumers with more favorable (unfavorable) attitudes toward counterfeits will have more favorable (unfavorable) behavioral intentions toward these products.

Conceptual model

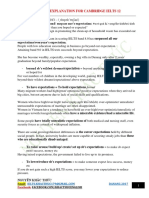

Based on the theoretical background just presented, Figure 1 shows the model proposed and submitted to empirical test.

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

Figure 1 Conceptual model for attitude toward counterfeited products

Comparing the scores of the scales with the demographic variables, no signicant differences were found between man and women, neither between different ranges of age, education nor income. Due to the data collection process (i.e. personal interview), questionnaires did not present missing values because interviewers were instructed to collect all the information from each participant. These data were submitted to the outliers analysis suggested by Hair et al. (1998, p. 69), namely computing the Mahalanobis distance and excluding cases with signicant high values. Using this procedure, 17 cases were identied and excluded from the data set. These cases were characterized as having lower means in the items referring to perceived risk and higher values in the propensity to buy counterfeited products, when compared to the rest of the sample. Analysis of variance showed signicant differences in these means ( p , 0.05). Linearity analysis was performed by checking the correlations between all items used in the questionnaire. Considering items from the same construct, the higher value found was 0.76 (i.e. items bi1-bi2 from Table I), suggesting there was no problem of multicollinearity in the data (see Tables II and III). Asymmetry was found in all variables when analyzing the normality graphs for each of them. Nevertheless, data were not submitted to transformations. Rather, the authors used different methods for estimating the 39

parameters, when testing the conceptual model, and compared the stability of the results. Dimensionality The scales used to measure the constructs of the conceptual model were submitted to the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) in order to test their dimensionality. Using Principal Axis Factoring as the extraction method and Oblimin as the rotation method and eigenvalues greater than one, seven factors were extracted (see Table IV). A simulation with other methods (e.g. Principal Components and Varimax rotation) produced similar results. Results presented in Table IV suggested that dimensionality was not found in only one case, between the constructs of attitude and behavioral intentions, which grouped together in one factor. Reliability and validity Scales were analyzed in terms of their reliability, by means of the internal consistency (Cronbachs alpha) and composite reliability (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), and also validity, considering convergent and discriminant validity. Reliability, initially assessed by Cronbachs alpha, was computed in two stages: considering the original items of each scale and after the exclusion of those with lower correlation with the scale. After this renement, values ranged from 0.46 (risk averseness) to 0.87 (integrity).

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

Table I Descriptive statistics

Scale Mean 3.86 3.64 4.80 5.44 6.38 6.38 3.13 2.15 2.76 2.83 2.27 3.47 2.95 SD 2.08 1.99 2.06 1.83 0.97 1.08 2.26 1.60 1.98 2.07 1.67 2.10 2.04

Price quality inference (Lichtenstein et al., 1993, Huang et al., 2004) PQ1 Generally speaking, the higher the price of a product, the higher the quality PQ2 The price of a product is a good indicator of its quality PQ3 You always have to pay a bit more for the best Risk averseness (Huang et al., 2004; Donthu and Garcia, 1999) RA1 When I buy something, I prefer not taking risks RA2 I like to be sure the product is a good one before buying it RA3 I dont like to feel uncertainty when I buy something. Attitude toward counterfeited products (Huang et al., 2004) AT1 Considering price, I prefer gray market goods AT2 I like shopping for gray market goods AT3 Buying gray market goods generally benets the consumer AT4 Theres nothing wrong with purchasing gray market goods. AT5 Generally speaking, buying gray market goods is a better choice Subjective norm (Ajzen, 1991) SN1 My relatives and friends approve my decision to buy counterfeited products SN2 My relatives and friends think that I should buy counterfeited products Behavioral intentions (Zeithaml et al., 1996) Considering today, what are the chances that you. . . BI1 . . .think about a counterfeited product as a choice when buying something BI2 . . .buy a counterfeited product BI3 ...recommend to friends and relatives that they buy a counterfeited product BI4 . . .say favorable things about counterfeited products Perceived risk (Dowling and Staelin, 1994) PR1 The risk that I take when I buy a counterfeited product is high PR2 There is high probability that the product doesnt work PR2 Spending money with a counterfeited product might be a bad decision Integrity (Ang et al., 2001) INT1 I consider honesty as an important quality for ones character INT2 I consider very important that people be polite INT3 I admire responsible people INT4 I like people that have self-control Personal gratication (Ang et al., 2001) PG I always attempt to have a sense of accomplishment

2.70 2.68 2.20 2.19 5.93 6.14 6.03 6.86 6.86 6.88 6.47 6.60

1.87 1.92 1.68 1.61 1.65 1.42 1.49 0.40 0.41 0.35 1.06 0.82

Another measure of reliability was also considered, namely the composite reliability. Results here were similar to those ones presented above, with lower values in the same scales of risk averseness (0.48). In all other scales the lower value found was 0.76, which is superior to the minimum of 0.70 suggested in the literature (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). This pattern of low values for the risk averseness scale is similar to the results presented by Huang et al. (2004), although they found values greater than the ones present here. The regression weights found for each item when running each constructs as a separate model were used as indication of Convergent Validity. This analysis, together with the reliability results presented above, was used to purify the constructs measures. Items with regression weights (i.e. lambdas) lower than 0.50 were excluded from the scale and the Cronbachs alpha, composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE) were recalculated (see Table V). In conjunction with the value of the lambdas, it was also checked its signicance 40

and the variance of the item explained by the construct (i.e. squared multiple correlation, SMC). Some constructs presented values of AVE below the lower bound of 0.50 suggested in the literature (e.g. Fornell and Larcker, 1981), although an improvement was reached after excluding the items with lambdas , 0.50. These constructs include: risk averseness (AVE 0:32), similar to what was found by Huang et al. (2004), when AVE 0:39, and attitude (AVE 0:45). Discriminant Validity was performed by comparing the shared variance between each pair of construct with the average variance extracted in each one of the pair (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Absolute values of correlation among constructs ranges from 0.025 (risk averseness-behavioral intentions) to 0.883 (attitude-behavioral intentions). Only in this case, the squared correlation (78 percent), indicating the shared variance, was higher then the AVE in attitude (45 percent) and in behavioral intentions (61 percent), then

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

Table II Correlations between items

PQ1 PQ1 PQ2 PQ3 RA1 RA2 RA3 DU AT1 AT2 AT3 AT4 AT5 SN1 SN2 B11 B12 B13 B14 PR1 PR2 PR3 PG INT1 INT2 INT3 INT4 1.00 0.59 * * 0.40 * * 0.09 0.02 0.07 2 0.11 * 0.02 0.02 0.09 2 0.15 * * 0.02 2 0.13 * 2 0.07 0.02 0.06 2 0.02 0.05 0.00 0.07 0.02 0.00 2 0.03 0.00 2 0.02 0.08 PQ2 1.00 0.36 * * 0.08 0.06 0.03 2 0.12 * 2 0.07 0.05 0.02 2 0.13 * * 0.01 2 0.10 2 0.07 2 0.03 0.05 2 0.06 0.01 2 0.01 2 0.01 2 0.01 0.03 2 0.04 2 0.02 2 0.03 2 0.02 PQ3 RA1 RA2 RA3 DU AT1 AT2 AT3 AT4 AT5 SN1

1.00 0.14 * * 0.12 * * 0.10 2 0.07 2 0.08 2 0.09 0.00 2 0.11 * 2 0.12 * 2 0.13 * 2 0.13 * 2 0.01 2 0.02 2 0.14 * * 2 0.13 * 0.11 * 0.07 0.04 0.13 * * 0.09 0.12 * 0.13 * 0.10 *

1.00 0.19 * * 0.18 * * 2 0.09 2 0.07 2 0.10 0.00 2 0.19 * * 2 0.13 * 2 0.04 0.04 0.01 2 0.03 2 0.14 * * 2 0.17 * * 0.14 * * 0.04 0.08 0.08 0.18 * * 0.27 * * 0.23 * * 0.03

1.00 0.30 * * 2 0.04 0.00 2 0.04 2 0.09 2 0.07 2 0.09 0.02 2 0.02 2 0.03 0.00 2 0.09 2 0.05 0.06 0.04 2 0.02 0.08 0.09 0.13 * 0.18 * * 0.16 * *

1.00 2 0.5 0.02 2 0.01 0.00 2 0.22 * * 2 0.16 * * 2 0.06 0.03 0.03 0.04 2 0.06 2 0.06 0.02 0.03 0.05 0.16 * * 0.17 * * 0.14 * * 0.19 * * 0.05

1.00 0.47 * * 0.36 * * 0.27 * * 0.18 * * 0.24 * * 0.25 * * 0.16 * * 0.38 * * 0.42 * * 0.35 * * 0.35 * * 0.06 2 0.10 * 2 0.20 * * 2 0.04 2 0.14 * * 2 0.06 2 0.05 0.01

1.00 0.47 * * 0.40 * * 0.14 * * 0.36 * * 0.29 * * 0.22 * * 0.48 * * 0.54 * * 0.44 * * 0.47 * * 2 0.14 * * 2 0.19 * * 2 0.32 * * 0.07 2 0.09 2 0.04 2 0.05 0.01

1.00 0.48 * * 0.25 * * 0.46 * * 0.20 * * 0.18 * * 0.47 * * 0.49 * * 0.51 * * 0.54 * * 2 0.20 * * 2 0.31 * * 2 0.34 * * 2 0.04 2 0.17 * * 2 0.18 * * 2 0.16 * * 0.02

1.00 0.12 * 0.52 * * 0.17 * * 0.15 * * 0.44 * * 0.43 * * 0.37 * * 0.45 * * 2 0.14 * * 2 0.26 * * 2 0.33 * * 0.02 2 0.08 2 0.11 * 2 0.18 * * 2 0.03

1.00 0.28 * * 0.19 * * 0.18 * * 0.17 * * 0.18 * * 0.24 * * 0.23 * * 2 0.15 * * 2 0.19 * * 2 0.16 * * 2 0.04 2 0.09 2 0.11 * 2 0.10 * 2 0.03

1.00 0.34 * * 0.26 * * 0.42 * * 0.41 * * 0.48 * * 0.55 * * 2 0.19 * * 2 0.34 * * 2 0.41 * * 2 0.12 * 2 0.29 * * 2 0.28 * * 2 0.32 * * 2 0.09

1.00 0.59 * * 0.35 * * 0.32 * * 0.26 * * 0.29 * * 2 0.06 2 0.14 * * 2 0.24 * * 0.01 2 0.02 0.00 2 0.03 2 0.13 * *

Notes: * Correlation is signicant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed); * * Correlation is signicant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Table III Correlations between items

SN2 PQ1 PQ2 PQ3 RA1 RA2 RA3 DU AT1 AT2 AT3 AT4 AT5 SN1 SN2 B11 B12 B13 B14 PR1 PR2 PR3 PG INT1 INT2 INT3 INT4 B11 B12 B13 B14 PR1 PR2 PR3 PG INT1 INT2 INT3 INT4

1.00 0.29 * * 0.23 * * 0.31 * * 0.29 * * 2 0.04 2 0.13 * 2 0.17 * * 2 0.02 2 0.09 2 0.08 2 0.11 * 0.00

1.00 0.76 * * 0.48 * * 0.52 * * 2 0.12 * 2 0.34 * * 2 0.40 * * 0.04 0.01 0.00 2 0.01 2 0.08

1.00 0.60 * * 0.61 * * 2 0.19 * * 2 0.32 * * 2 0.44 * * 0.00 2 0.06 2 0.07 2 0.07 2 0.08

1.00 0.66 * * 2 0.22 * * 2 0.33 * * 2 0.40 * * 2 0.10 * 2 0.26 * * 2 0.21 * * 2 0.19 * * 0.02

1.00 2 0.25 * * 2 0.32 * * 2 0.41 * * 2 0.05 2 0.21 * * 2 0.26 * * 2 0.25 * * 2 0.04

1.00 2 0.43 * * 2 0.32 * * 0.05 0.09 0.17 * * 0.17 * * 0.08

1.00 2 0.62 * * 0.16 * * 0.13 * 0.11 * 0.13 * * 0.06

1.00 0.12 * 0.09 0.11 * 0.13 * * 0.10

1.00 0.33 * * 0.23 * * 0.24 * * 0.08

1.00 0.67 * * 0.69 * * 0.14 * *

1.00 0.74 * * 0.20 * *

1.00 0.20 * *

1.00

Notes: * Correlation is signicant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed); * * Correlation is signicant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

41

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

Table IV Dimensionality test by exploratory factor analysis

Items BI2 BI1 BI4 AT1 AT2 BI3 AT3 AT5 INT2 INT3 INT1 PQ1 PQ2 PQ3 PR2 PR3 PR1 SN1 SN2 RA3 RA2 RA1 AT4 Variance explained Attitude/behavioral intentions Integrity 0.077 0.158 2 0.129 0.042 2 0.056 2 0.110 2 0.015 2 0.167 0.863 0.850 0.793 2 0.055 2 0.059 0.087 2 0.049 2 0.044 0.071 0.052 2 0.098 2 0.043 0.010 0.152 0.036 9.3 Factors Price-quality relation 0.035 0.013 0.008 2 0.059 0.005 2 0.070 0.079 0.062 0.021 2 0.027 2 0.025 0.796 0.755 0.490 0.001 2 0.025 0.017 2 0.020 2 0.013 2 0.060 0.004 0.103 2 0.110 6.3 Perceived risk 2 0.025 2 0.039 2 0.026 0.068 2 0.050 2 0.047 2 0.039 2 0.123 0.008 0.031 2 0.004 0.067 2 0.067 0.015 0.986 0.586 0.453 0.001 0.021 0.008 2 0.034 0.005 2 0.097 3.9 Subjective norm 2 0.017 2 0.103 2 0.040 2 0.026 0.063 2 0.052 0.043 2 0.169 2 0.013 0.038 0.039 0.017 2 0.026 0.041 0.019 0.063 2 0.059 2 0.788 2 0.733 0.051 2 0.046 2 0.077 2 0.118 2.8 Risk aversion 2 0.089 2 0.051 0.051 2 0.044 0.021 0.036 0.035 0.180 0.031 2 0.037 0.021 0.037 0.039 2 0.066 0.049 0.019 2 0.023 0.058 2 0.066 2 0.679 2 0.427 2 0.293 0.291 2.4

0.827 0.722 0.714 0.680 0.673 0.644 0.596 0.436 2 0.009 0.022 2 0.001 0.108 2 0.037 2 0.017 0.100 2 0.204 2 0.023 0.031 0.004 0.112 2 0.023 2 0.057 0.123 20.1

Notes: Total variance explained: 50.54%; item int4 was excluded because it load alone as a different factor; Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy 0:833; Bartletts Test of Sphericity: x2 3:351; df 253; p , 0.000

failing to suggest discriminant validity (see results in Table VI). Using another criteria (Bagozzi and Philips, 1982) and constraining this correlation to unity produced a signicant change in the goodness-of-t statistic (Dx2 25:389; df 1; p , 0.000). We used as additional evidence of discriminant validity between these constructs further evidence obtained when testing the full model (i.e. signicant predictors of attitude were not signicant predictors of behavioral intentions), which will be presented ahead. Estimation of model parameters After the process of scale renement presented above, the conceptual model with the remaining indicators (see Figure 1) was submitted to test. Results using both the maximumlikelihood (ML) method and the generalized least squares (GLS) show that the t indexes approximate acceptable levels using ML (i.e. GFI 0:898; AGFI 0:854; NFI 0:874; CFI 0:917; PACFI 0:703; RMSEA 0:064) and using GLS (i.e. GFI 0:928; AGFI 0:897; NFI 0:666; CFI 0:806; PACFI 0:622; RMSEA 0:045), considering the measurement literature (e.g., Byrne, 2001). In both methods, however, chi-square parameter was signicant ( p , 0.000). Since chi-square is sensitive to sample size, relative chi-square (x2/df) is commonly suggested in the measurement literature. Using ML method, a value of 2.575 was found for the relative chi-square, which is in the acceptable level of 2 or 3 to 1 (Arbuckle, 1997). Because similar results were also found for the coefcients when using both ML and GLS, only those produced by the 42

ML, the most frequently used method (Thompson, 2002), are presented (see Table VII). Considering the antecedents of attitudes, signicant paths were found for perceived risk ( p , 0.000), integrity ( p , 0.002), personal gratication ( p , 0.015), subjective norm ( p , 0.000) and the dummy ( p , 0.000), supporting H3, H4, H5, H6, H7A respectively. Only risk averseness was a nonsignicant antecedent ( p , 0.933), failing to support H2. Contrary to expectations, however, results showed a positive relationship between price-quality and attitude ( p , 0.009), failing to support H1. Results revealed also that attitude toward counterfeits is most signicantly affected by the following constructs: perceived risk (b 20:487); dummy have bought a counterfeit before or not (b 0:347), subjective norm (b 0:245), integrity (b 0:157), price-quality inference (b 0:149) and personal gratication (b 0:109). In this order, these variables are the most important for explaining consumer attitude toward counterfeited products. When assessing the variables inuencing behavioral intentions, it was found that attitude was signicant ( p , 0.000; b 0:891), supporting H8; but the dummy have bought a counterfeit before or not was not ( p , 0.493; b 0:033), not supporting H7B. This result is interesting because it shows a mediating effect of attitude in the relationship between the dummy, a proxy of consumer previous experience with counterfeits, and intentions to buy a counterfeit. In other words, experience inuences attitudes, which in turn inuences behavior.

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

Table V Summary of constructs measures

Scale Cronbachs alpha (a) Composite reliability (CR) Average variance extracted (AVE) Price-quality relation a 5 0:71; CR 5 0:72; AVE 5 0:48 a a 5 0:74; CR 5 0:76; AVE 5 0:62 Attitude toward counterfeit a 5 0:70; CR 5 0:74 AVE 5 0:38 a a 5 0:75; CR 5 0:76; AVE 5 0:45

Items pq1 pq2 pq3 * at1 at2 at3 at4 * at5 bi1 bi2 bi3 bi4 pr1 * pr2 pr3 int1 int2 int3 int4 * sn1 sn2 ra1 * ra2 ra3

Standardized regression weights 0.810 0.726 0.497 0.583 0.712 0.692 0.301 0.686 0.803 0.911 0.676 0.700 0.471 0.918 0.676 0.789 0.849 0.877 0.221 0.680 0.860 0.339 0.558 0.540

t

8.162 7.519 9.332 9.215 4.911 9.179 18.168 13.711 14.302 6.876 8.282 17.237 17.497 4.094 7.58 3.358 3.432

p

0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.001 0.001

Squared multiple correlations (SMC) 0.657 0.527 0.247 0.340 0.507 0.478 0.091 0.471 0.644 0.830 0.457 0.490 0.222 0.843 0.458 0.622 0.721 0.770 0.049 0.463 0.115 0.311 0.292

Behavioral intentions a 5 0:85; CR 5 0:86; AVE 5 0:61

Perceived risk a 5 0:71; CR 5 0:74; AVE 5 0:51 a a 5 0:76; CR 5 0:77; AVE 5 0:63 Integrity a 5 0:53; CR 5 0:80; AVE 5 0:54 a a 5 0:87; CR 5 0:88; AVE 5 0:70 Subjective norm a 5 0:74; CR 5 0:75; AVE 5 0:60 Risk averseness a 5 0:39; CR 5 0:48; AVE 5 0:24 a a 5 0:46; CR 5 0:48; AVE 5 0:32

Notes: * Excluded due to low weights (, 0.5); a values for the puried scale; Fit statistics after purication process (measurement model): chi square 403:50; df 155; p , 0.000; GFI 0:901; AGFI 0:853; CFI 0:919; RMSEA 0:065

In order to test which of the exogenous construct from Figure 1 would have a signicant inuence on behavioral intentions, an alternative model was also tested, in which constructs are modeled to inuence both attitudes and behavioral intentions. As a result, it was found that most variables signicantly affect attitudes but not behavioral intentions (i.e. price-quality inference, subjective norm, perceived risk, integrity, dummy and personal gratication), and only one did not affect either of them (i.e. risk averseness). This nding can be interpreted as an indication of parsimony in the original conceptualized model and it also reinforces the mediating role of attitudes in the relationship between the key reviewed antecedents and the behavioral intentions. It is also an interesting result because, considering the high amount of shared variance between attitudes and behavioral intentions, one would expect that constructs with a signicant effect on attitudes would also have a signicant effect on behavioral intentions. This not being the case suggests the discriminant validity between attitudes and behavioral intentions. When comparing consumers who have bought a counterfeit with those who afrmed that have never bought a counterfeit, it was found that the former have more favorable attitudes (M havebought 0:28, M haveneverbought 20:66, p , 0.000) and 43

behavioral intentions ( M havebought 0:29, M haveneverbought 20:68, p , 0.000), tend to disagree with the notion that high price means high quality (M havebought 20:08, M haveneverbought 0:20, p , 0.012), agree more on the question that their friends and relatives approve their decision to buy counterfeits (M havebought 0:15, M haveneverbought 20:35, p , 0.000), perceive less risk in the counterfeit (M havebought 20:11, M haveneverbought 0:26, p , 0.001) and have lower scores on integrity (M havebought 20:06, M haveneverbought 0:14, p , 0.065). These results support H7.

Discussion

Although gray market has grown worldwide, research from a demand perspective remains scarce as emphasized by Huang et al. (2004). In order to ll this void, this paper aimed to investigate the key antecedents of consumer attitudes toward counterfeits, as well as the inuence of this attitude on the behavioral intentions toward these products. Based on recent marketing literature, this article integrates two conceptual models, one proposed and tested by Huang et al. (2004), who considered price-consciousness, price-quality inference and risk averseness as antecedents of consumer attitudes, and the

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

Table VI Discriminant validity by squared correlations and AVE

PQ Price-quality (PQ) Risk aversion (RA) Subjective norm (SN) Perceived risk (PR) Integrity (IN) Attitude (AT) Behavioral intentions (BI) RA SN PR IN AT BI

0.624 0.011 0.023 0.002 0.001 0.003 0.002

0.322 0.002 0.004 0.102 0.012 0.001

0.601 0.084 0.003 0.188 0.216

0.63 0.029 0.705 0.361 0.088 0.447 0.356 0.030 0.780 0.611

Notes: Numbers in italic are the AVE for the construct; for scales with only two items (e.g. SN); the loadings used for computing AVE were those obtained when modeling all constructs correlated with each other (measurement model)

Table VII Parameter estimation

Standardized Critical weights ratios (b) (t) 0.149 0.005 0.245 2 0.487 2 0.157 0.347 0.109 0.891 0.033 0.643 0.915 0.648 0.465 0.672 0.871 0.858 0.724 0.843 0.798 0.876 0.656 0.694 0.627 0.664 0.773 0.844 0.731 0.772 2.604 0.084 4.114 2 7.262 2 3.067 6.722 2.435 10.812 0.685 3.937

Relations AT AT AT AT AT AT AT BI BI pq2 pq1 ra3 ra2 sn2 sn1 pr3 pr2 int2 int1 int3 at1 at2 at3 at5 bi1 bi2 bi3 bi4 PQ RA SN PR IN DU PG AT DU PQ PQ RA RA SN SN PR PR IN IN IN AT AT AT AT BI BI BI BI

Regression Standard weights errors 0.115 0.013 0.2 2 0.582 2 0.733 1.126 0.208 0.857 0.103 0.667 1 1 0.673 0.752 1 1 0.803 0.985 1 0.96 1 0.741 0.825 0.743 1 1.119 0.837 0.847 0.044 0.15 0.049 0.08 0.239 0.168 0.085 0.079 0.15 0.169

p

0.009 0.933 0.000 0.000 0.002 0.000 0.015 0.000 0.493 0.000

0.219 0.102

3.073 0.002 7.372 0.000

0.076 0.056 0.054 0.064 0.078 0.067 0.065 0.057 0.055

10.606 0.000 17.444 0.000 17.863 0.000 11.558 0.000 10.611 0.000 11.133 0.000 17.138 0.000 14.574 0.000 15.511 0.000

Notes: SMC: attitude 0:642; behavioral intentions 0:825

other proposed by Ang et al. (2001), who considered social factors (i.e. informative susceptibility and normative susceptibility) and personality factors (i.e. value consciousness, integrity and personal gratication) as antecedents of consumer attitudes. The study presented here considered as antecedents a combination of these factors presented above. Two constructs 44

are similar in content when comparing these two models: price-consciousness and value consciousness, meaning the concern for paying lower prices, subject to some quality constraint (Lichtenstein et al., 1993). In their study, Ang et al. (2001) found that consumers who were more value conscious had a more favorable attitude towards piracy than less value conscious consumers. On the other hand, in Huang et al. (2004)s study, the price-consciousness construct was not signicant. In the present research, this construct was not included. It remains, however, as an interesting relationship to be tested in future research. In the sense of combination of factors from both models, subjective norm was considered as representing the social inuence. The authors also included a new construct in the model in order to better explain the risk component, which was the risk consumers perceive when they buy a counterfeit. This variable was not considered in either of the two models presented above. Perceived risk is more specic than risk averseness because the former deals with how much risk consumer perceive when s/he buys a counterfeit while the latter indicates only the consumer propensity to take risks overall. Although some constructs had a relative small average variance extracted (e.g., risk averseness) and some of the t indexes obtained in the model only approximate the desired level (e.g. GFI should be higher than 0.9), 82.5 percent of the variance in the behavioral intentions and 64 percent of the variance in the attitudes could be explained by the variables in the model (i.e. considering Squared Multiple Correlations, SMC for these constructs). These values are rather considerable, especially considering previous research (e.g., in the study by Ang et al., 2001, adjusted R2 was equal to 0.44 for the model predicting purchase intentions). Results from this extended model revealed that perceived risk was the most important variable to predict consumer attitude toward counterfeits, followed by the fact that he/she have bought a counterfeit before or not, subjective norm, integrity, price-quality inference and personal gratication. Consumers who perceived more risk in the counterfeits had unfavorable attitudes toward them, in line with previous research dealing with perceived risk (e.g. Dowling and Staelin, 1994). Those consumers who had already bought a counterfeit had favorable attitude toward it. Those consumers whose relative and friends approve their decision to buy counterfeits have more favorable attitudes, a result convergent with the predictions of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Consumers who considered important values as honesty, politeness and responsibility tended to have a negative attitude toward counterfeits, in accordance with previous research (e.g. Ang et al., 2001, Cordell et al., 1996), but those who seek to have a sense of accomplishment have positive attitudes, different from Ang et al.s study, which found a positive but non signicant effect. Finally, those consumers who considered the price as an indication of quality had more favorable attitudes toward counterfeits, which is contrary to the results found by Huang et al. (2004) and the prediction made in H1. In this case of the price-quality inference, it was hypothesized that consumers considering high price, high quality and low price, low quality would have unfavorable attitudes toward counterfeits because of its inferior price. Results suggested that this was not the case, or at least that consumers who are used to buy counterfeits may apply this rule to the gray market in itself (i.e. those counterfeits of inferior price are perceived as low

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

quality and those ones of higher prices as higher quality). This can be an important alternative explanation especially if one considers that 70 percent of the respondents in this study had already bought a counterfeit. Only the construct risk averseness did not have a signicant inuence on attitudes, which is different from the result presented by Huang et al. (2004). This nding is interesting if one considers that perceived risk was the most important predictor. A possible explanation is the difference in meaning between them and also the easiness with each respondents probably related the perceived risk items to the context of the research, maybe having difcult to do so in the risk averseness items. This difference, however, should be considered in future investigations. Because previous research reviewed did not mention the direct effect of the antecedents of attitudes on purchase/ behavioral intentions, one important contribution of this paper is also to show that the signicant predictors of attitudes presented above do not have a direct inuence on consumers behavioral intentions, even though attitudes and behavioral intentions are highly correlated in this study. This is an evidence of the mediator role of attitude: the key constructs affect attitudes, which in turn affect behavioral intentions. The relative importance of these predictors can also contribute to the policy makers or managers of international brands who should use the perceived risk as the main appeal in the messages intended to discourage consumption of counterfeits. Another important point is that those consumers who have bought a counterfeit have more favorable attitudes when compared to those who have not. This is a real threat for the original brands, because once consumers experiment the counterfeit, they tend to have a favorable attitude and then have a positive behavioral intentions. The results suggested, however, that this experience does not have a direct effect on behavioral intentions. In this way, it is possible to inuence attitudes consumers have toward counterfeits through other variables, for example, by inuencing the (negative) perceived social acceptance consumer will have when buying a counterfeit. This would be the practical implication of the signicant effect of the construct subjective norm. Another alternative could be trying to inuence consumer personality, such as integrity, although this one is more difcult to change, encouraging consumers to consider values as responsibility and honesty in their life. It was found that consumers who attempt to have a sense of accomplishment had more favorable attitudes toward counterfeits. These consumers may consume counterfeits as an opportunity to experiment a product innovation, which can be more salient for electronic products. This could be even more signicant for low-income consumers, which can be investigated in future research. In terms of demographic variables, results are convergent with previous research when nding that consumers of counterfeits have more favorable attitudes and behavioral intentions (Ang et al., 2001). This might be a problem for those trying to reduce the counterfeit consumption, because if these consumers are satised with the performance of the pirated product, there will be more resistance for attitude change. It was also found that these consumers: . do not use price as a reference of quality; . consider that the reference groups approve their decision to buy counterfeits, which can be viewed as a strategy to reduce cognitive dissonance; and . are not afraid that the counterfeit will not work properly. 45

Conclusions and suggestions

This research contributes to the existing literature by extending and testing the key antecedents of the consumer attitudes toward counterfeits. It also identies the relative importance of each antecedent in predicting attitudes. It is argued that these attitudes act as mediator in the relation between the constructs considered and the behavioral intentions. Another contribution is related to the practical implications of this paper, when it considers the strategies managers can use for dealing with the problem of consumers loosing loyalty in the brands and turning into counterfeits. As suggestions for future research, one could test the model presented here in different product categories (e.g. CDs, DVDs, clothes, toys etc) and check for possible differences. It is also recommended that new important variables be included in the model, which can be done by searching for moderators and boundary conditions. This might be the case of consumer involvement with the product, for instance. It should be expected that when consumers are more involved with the product, he/she should be more worried about the buying decision and have a higher risk aversion.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991), The theory of planned behavior, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 50 No. 2, pp. 179-211. Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980), Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Albers-Miller, N.D. (1999), Consumer misbehavior: why people buy illicit goods, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 273-87. Ang, S.H., Cheng, P.S., Lim, E.A.C. and Tambyah, S.K. (2001), Spot the difference: consumer responses towards counterfeits, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 18 No. 3, pp. 219-35. Arbuckle, J.L. (1997), AMOS Users Guide: Version 3.6, SPSS, Chicago, IL. Bagozzi, R. and Philips, L.W. (1982), Representing and testing organizational theories: a holistic construal, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 459-90. Bagozzi, R.P., Gu rhan-Canli, Z. and Priester, J.R. (2002), The Social Psychology of Consumer Behavior, Open University Press, Buckingham. Bearden, W.O., Netemeyer, R.G. and Teel, J.E. (1989), Measurement of consumer susceptibility to interpersonal inuence, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 473-81. Byrne, B.M. (2001), Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ. Bloch, P.H., Bush, R.F. and Campbell, L. (1993), Consumer Accomplices in product counterfeiting; a demand side investigation, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 10 No. 4, pp. 27-36. Bonoma, T.V. and Johnston, W.J. (1979), Decision making under uncertainty: a direct measurement approach, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 177-91. Chapman, J. and Wahlers, A. (1999), revision and empirical test of the extended price-perceived quality model, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 53-64.

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

Cespedes, F.V., Corey, E.R. and Rangan, V.K. (1988), Gray markets: causes and cures, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 66 No. 4, pp. 75-83. Chaudhry, P., Cordell, V. and Zimmerman, A. (2005), Modeling anti-counterfeiting strategies in response to protecting intellectual property rights in a global environment, Marketing Review, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 59-72. Cordell, V., Wongtada, N. and Kieschnick, R.L. Jr (1996), Counterfeit purchase intentions: role of lawfulness attitudes and product traits as determinants, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 41-53. Donthu, N. and Garcia, A. (1999), The Internet shopper, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 39 No. 3, pp. 52-8. Dowling, G.R. and Staelin, R. (1994), A model of perceived risk and intended risk-handling activity, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 119-34. Eagly, A.H. and Chaiken, S. (1993), The Psychology of Attitudes, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Fort Worth, TX. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981), Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50. Gerbing, D.W. and Anderson, J.C. (1988), Un updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 25, May, pp. 186-92. Hair, J.F. Jr, Anderson, R.E., Tatham, W. and Black, W.C. (1998), Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed., Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Havlena, W.J. and DeSarbo, W.S. (1991), On the measurement of perceived consumer risk, Decision Sciences, Vol. 22 No. 4, pp. 927-39. Huang, J.H., Lee, B.C.Y. and Ho, S.H. (2004), Consumer attitude toward gray market goods, International Marketing Review, Vol. 21 No. 6, pp. 598-614. International Anticounterfeiting Coalition (2005), Facts on fakes, available at: www.iacc.org/Facts.html (accessed November 30, 2005). International Intellectual Property Institute (2003), Counterfeit goods and the publics health and safety, available at: www.iacc.org/IIPI.pdf (accessed November 30, 2005). Kim, M.S. and Hunter, J.E. (1993), Relationships among attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behavior: a metaanalysis of past research, Part 2, Communication Research, Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 331-64. Lichtenstein, D.R., Ridgway, N.M. and Netemeyer, R.G. (1993), Price perceptions and consumer shopping behavior: a eld study, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 30 No. 2, pp. 234-45. Schiffman, L.G. and Kanuk, L.L. (1997), Consumer Behavior, 8th ed., Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Tellis, G.J. and Gaeth, G.J. (1990), Best value, priceseeking, and price aversion: the impact of information and learning on consumer choices, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 54, April, pp. 34-45. Thompson, B. (2002), Ten commandments of structural equation modeling, in Grimm, L.G. and Yarnold, P.R. (Eds), Reading and Understanding More Multivariate Statistics , American Psychological Association, Washington, DC. 46

Zeithaml, V.A., Parasuraman, A. and Berry, L.L. (1996), The behavioral consequences of service quality, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60, April, pp. 31-43. Zinkhan, G.M. and Karande, K.W. (1990), Cultural and gender differences in risk-taking behavior among American and Spanish decision markers, The Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 131 No. 5, pp. 741-2.

Further reading

Blackwell, R.D., Miniard, P.W. and Engel, J.F. (1995), Consumer Behavior, The Dryden Press, Orlando, FL. Hubbard, R. and Armstrong, J.S. (1994), Replications and Extensions in marketing: rarely published but quite contrary, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 11, pp. 233-48.

About the authors

Celso Augusto de Matos is a marketing doctoral candidate at the School of Management at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (PPGA-EA-UFRGS). His research interests are in the areas of attitude formation and change, consumer behavior in services, and marketing research. His research has been published in the International Journal of Consumer Studies, Brazilian Administration Review, ACR conference and in a number of Brazilian journals and proceedings. He is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: celsomatos@yahoo.com.br Cristiana Trindade Ituassu holds a masters degree from the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil (CEPEADUFMG). Her research interests are in the areas of country image, consumer behavior, and advertising. Her research has been published in a number of Brazilian proceedings. Dr Carlos Alberto Vargas Rossi is a professor at the School of Management at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (PPGA-EA-UFRGS). His research interests are in the areas of strategic marketing, consumer behavior, and marketing theory. His research has been published in the International Journal of Consumer Studies, Brazilian Administration Review, ACR conference and in a number of Brazilian journals and proceedings.

Executive summary and implications for managers and executives

This summary has been provided to allow managers and executives a rapid appreciation of the content of this article in toto to take advantage of the more comprehensive description of the research undertaken and its results to get the full benet of the material present. There is plenty of evidence to prove that the sale of counterfeit goods is a growing cause for concern. Around 5 percent of products worldwide are believed to be fake, while the problem costs the US economy over $200 billion every year. Despite this level of concern, scant research exists into the purchasing of pirated goods particularly from a consumer perspective. Inuential factors Previous studies have, however, identied several factors that may inuence consumer intention towards counterfeit

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits Celso Augusto de Matos et al.

Journal of Consumer Marketing Volume 24 Number 1 2007 36 47

products. The factors operate at individual and interpersonal level and include: . Price-quality correlation. A belief that many consumers equate product quality from its price and the level of guarantee offered. Specically, many theorists believe that the typically lower cost of pirated goods leads the consumer to assume lower quality also. . Risk aversion and perceived risk. Research has proven that some consumers possess a personality trait making them averse to risk taking and has shown this trait to be a signicant factor in whether or not the consumer will make purchases deemed risky. Buying online is one example that many people regard as involving risk. Some consumers perceive more specic risks that can relate not only to price and quality but also to safety, nance, performance, social or psychological. . Integrity. The ethical standards of the consumer. . Subjective norm. How pressure from relatives and friends can lead individuals to adopt certain attitudes and behaviors. . Previous experience. Whether or not the consumer has previously bought pirated goods. . Personal fulllment. How individuals perceive themselves. Earlier studies have provided conicting evidence in regard to this factor. Some researchers found little evidence of links between personal fulllment and counterfeit goods, while others discovered that those buying such products regarded themselves as less condent, being lower achievers, having less money and being of inferior standing than non-buyers. . Behavioral intentions. Other studies have indicated strong links between attitude and intention, and that intention is a reliable predictor of actual behavior. Two existing conceptual models each considered the impact of some of the above factors. De Matos et al. extend this work by combining the models and investigating a range of hypotheses relating to all the factors. Survey and ndings The authors conducted a survey in areas of two large Brazilian cities where counterfeit goods were on sale. Interviews were carried out in the streets and the sample obtained included respondents with different age, gender, income and education proles. In response to a question about previous purchases, 70 percent of the 400 surveyed admitted they had already bought fake goods. For other questions, respondents answered on a scale ranging from completely agree to completely disagree apart from behavioral intentions, where answers ranged from very likely to very unlikely. The responses indicated that no real importance could be attached to gender, age, income level or education. Contrary to expectation, the study did not provide sufcient evidence to imply that consumers who rmly believe in the price-quality link will have a more negative attitude towards counterfeit products. Indeed, many participants who considered that quality is indicated by price revealed more rather than less favorable attitudes. The authors speculate that consumers might in fact apply the price-quality inference within the counterfeit market itself

particularly given the high number of respondents who had previously bought such products. The assumption that higher levels of risk aversion would have a similar effect was also unproven. De Matos et al. express particular surprise at the latter ndings given that perceived risk was discovered to be the most inuential of all factors considered. Prior purchase was next, followed by subjective norms, integrity, price-quality inference and personal gratication. Importantly, evidence suggests that these factors inuence consumer attitude towards pirated goods but do not directly inuence purchase intention. The authors note the complexity of this issue given that attitude was found to inuence intention. Most other ndings were as anticipated and concurred with previous studies. For instance, consumers who valued honesty and responsibility generally display a negative attitude towards counterfeits. Likewise, there was also considerable support for the theory that peer approval or disapproval affects consumer attitude. The results of the survey enabled de Matos et al. to build a prole of a consumer most likely to buy fake goods. Such a consumer would probably have a more favorable attitude and purchase intention towards counterfeits, tend to disagree with the notion that higher price means better quality, perceive less risk, places lower value on integrity. In the survey itself, these respondents also revealed higher levels of agreement in relation to the question about peer approval of their purchases. Implications and suggestions for future research The authors believe that the study can aid marketers in the battle to dissuade consumers from purchasing counterfeit products. Given that perceived risk was most inuential, they suggest that the most effective results may be possible if this factor is at the core of advertising campaigns. However, if the consumer has previously bought pirated goods the challenge becomes more difcult and is compounded further when he or she is satised with these purchases. In this instance, de Matos et al. propose that trying to inuence the social acceptance factor may be the best tactic to adopt. Attempting to inuence integrity is another option, although the authors acknowledge the difculties inherent in persuading individuals to reect on the values they hold. In view of the inconclusiveness, further investigation of the price-quality link could prove fruitful, as might additional exploration into the relationship between risk averseness and perceived risk. The authors also point out that the survey focused on general rather than specic counterfeit products and suggest that consideration of different product categories may be informative. For example, they speculate that lower income consumers who value personal accomplishment may experience innovation through the purchase of counterfeit electrical or other hi-tech products. Inclusion of other variables such as consumer involvement with the product may likewise prove to be signicant. cis of the article Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits: (A pre a review and extension. Supplied by Marketing Consultants for Emerald.)

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

47

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Programming Language Foundations PDFDocumento338 pagineProgramming Language Foundations PDFTOURE100% (2)

- Key formulas for introductory statisticsDocumento8 pagineKey formulas for introductory statisticsimam awaluddinNessuna valutazione finora

- Micropolar Fluid Flow Near The Stagnation On A Vertical Plate With Prescribed Wall Heat Flux in Presence of Magnetic FieldDocumento8 pagineMicropolar Fluid Flow Near The Stagnation On A Vertical Plate With Prescribed Wall Heat Flux in Presence of Magnetic FieldIJBSS,ISSN:2319-2968Nessuna valutazione finora

- MMW FinalsDocumento4 pagineMMW FinalsAsh LiwanagNessuna valutazione finora

- THE PEOPLE OF FARSCAPEDocumento29 pagineTHE PEOPLE OF FARSCAPEedemaitreNessuna valutazione finora

- Kahveci: OzkanDocumento2 pagineKahveci: OzkanVictor SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- Individual Assignment ScribdDocumento4 pagineIndividual Assignment ScribdDharna KachrooNessuna valutazione finora

- Ali ExpressDocumento3 pagineAli ExpressAnsa AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 1 - International Banking Meaning: Banking Transactions Crossing National Boundaries Are CalledDocumento6 pagineUnit 1 - International Banking Meaning: Banking Transactions Crossing National Boundaries Are CalledGanesh medisettiNessuna valutazione finora

- ExpDocumento425 pagineExpVinay KamatNessuna valutazione finora

- School Quality Improvement System PowerpointDocumento95 pagineSchool Quality Improvement System PowerpointLong Beach PostNessuna valutazione finora

- SWOT Analysis of Solar Energy in India: Abdul Khader.J Mohamed Idris.PDocumento4 pagineSWOT Analysis of Solar Energy in India: Abdul Khader.J Mohamed Idris.PSuhas VaishnavNessuna valutazione finora

- SEO Design ExamplesDocumento10 pagineSEO Design ExamplesAnonymous YDwBCtsNessuna valutazione finora

- Cells in The Urine SedimentDocumento3 pagineCells in The Urine SedimentTaufan LutfiNessuna valutazione finora

- Numerical Methods: Jeffrey R. ChasnovDocumento60 pagineNumerical Methods: Jeffrey R. Chasnov2120 sanika GaikwadNessuna valutazione finora

- Desert Power India 2050Documento231 pagineDesert Power India 2050suraj jhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Individual Sports Prelim ExamDocumento13 pagineIndividual Sports Prelim ExamTommy MarcelinoNessuna valutazione finora

- IELTS Vocabulary ExpectationDocumento3 pagineIELTS Vocabulary ExpectationPham Ba DatNessuna valutazione finora

- Recycle Used Motor Oil With Tongrui PurifiersDocumento12 pagineRecycle Used Motor Oil With Tongrui PurifiersRégis Ongollo100% (1)

- Modern Indian HistoryDocumento146 pagineModern Indian HistoryJohn BoscoNessuna valutazione finora

- 14 15 XII Chem Organic ChaptDocumento2 pagine14 15 XII Chem Organic ChaptsubiNessuna valutazione finora

- Abinisio GDE HelpDocumento221 pagineAbinisio GDE HelpvenkatesanmuraliNessuna valutazione finora

- Instagram Dan Buli Siber Dalam Kalangan Remaja Di Malaysia: Jasmyn Tan YuxuanDocumento13 pagineInstagram Dan Buli Siber Dalam Kalangan Remaja Di Malaysia: Jasmyn Tan YuxuanXiu Jiuan SimNessuna valutazione finora

- Ks3 Science 2008 Level 5 7 Paper 1Documento28 pagineKs3 Science 2008 Level 5 7 Paper 1Saima Usman - 41700/TCHR/MGBNessuna valutazione finora

- Newcomers Guide To The Canadian Job MarketDocumento47 pagineNewcomers Guide To The Canadian Job MarketSS NairNessuna valutazione finora

- Creatures Since Possible Tanks Regarding Dengue Transmission A Planned Out ReviewjnspeDocumento1 paginaCreatures Since Possible Tanks Regarding Dengue Transmission A Planned Out Reviewjnspeclientsunday82Nessuna valutazione finora

- USA V BRACKLEY Jan6th Criminal ComplaintDocumento11 pagineUSA V BRACKLEY Jan6th Criminal ComplaintFile 411Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 1 Writing. Exercise 1Documento316 pagineUnit 1 Writing. Exercise 1Hoài Thương NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- Imaging Approach in Acute Abdomen: DR - Parvathy S NairDocumento44 pagineImaging Approach in Acute Abdomen: DR - Parvathy S Nairabidin9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Microsoft Word 2000 IntroductionDocumento72 pagineMicrosoft Word 2000 IntroductionYsmech SalazarNessuna valutazione finora