Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Rooting and Sucking Reflexes

Caricato da

papang_bahtiarTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Rooting and Sucking Reflexes

Caricato da

papang_bahtiarCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Rooting and Sucking Reflexes A hungry infant will turn the head to the right or left when the

cheek is brushed by a hand or facecloth. If a nipple is touched to the face whether to the right or left, above or below the mouth-the lips and tongue will tend to follow in that direction. These rooting and sucking reflexes should be present in all full-term babies. As might be expected, they are more easily elicited before than after a feeding. The reflexes may be absent in small prematures. Absence among full-term infants suggests depression of the central nervous system from maternal anesthesia, hypoxia, or congenital defect.

Rooting reflex These responses usually last until the infant is 3 or 4 months old. However, the rooting response may persist during sleep until as late as 7 or 8 months. At later ages, visual stimulation plays a part-babies may root for a bottle but may not respond to the touch of a finger. Persistence of the response beyond the 7th month, or its reappearance later in life, warrant thorough medical evaluation.

While rooting and sucking reflexes are being appraised, attention should also be given to the possible presence of such anomalies as a particularly small chin, a face that appears unusually fat in relation to a rather small skull, peculiar dentition (such as double-fused teeth), a cleft lip or palate, or asymmetry of the nasolabial folds. Excess salivation, mucus, and frothing always warrant attention. Feeding problems are discussed later. The Moro Reflex The Moro reflex, sometimes termed a "startle" reflex, is a series of movements by an infant in response to a stimulus. The pattern of movement varies among infants, and gradually alters during the first few months of life with increasing maturity. It is not possible, therefore, to give a single description for all ages and all infants. Mitchell described the reflex in the infant a few days old:

The initial part of the response is extension and abduction of the upper ex- tremities with extension of the spine and retraction of the head. The forearms are supinated and the digits tend to extend and fan out, with the exception of the distal phalanges of the index finger and thumb, which may be C-shaped ... the upper extremities describe an arc-like movement, bringing the hands towards one another in front of the body, and finally return to the position of flexion and abduction [Mitchell, 1960, p. 9].

Sometimes there is a slight tremor or even a rhythmic shaking of the limbs. The movement of the lower extremities is usally less pronounced. Both legs tend to extend and abduct with the upper extremities, although there may be a slight movement of flexion first. If the lower extremities are extended when the stimulus is applied, the flexion movements may be more readily noted. A sudden jolting movement, such as that produced by striking the mattress or table on both sides of the infant, will usually cause the startle response. Occasionally a loud noise may precipitate the reflex. Extension of the head relative to the trunk or a sudden strong stimulus appear to be the most reliable means of eliciting the reflex.

Moro reflex The Moro reflex is strongest during approximately the first 8 weeks of life. Thereafter, it becomes less pronounced. McGraw (1937) found that most infants change at about 90 days from the newborn phase to a transitional phase in which movements become less gross, and at about 130 days to the final "body-jerk" phase. Persistence of the Moro reflex after the 6th month should be considered suspicious and deserves careful medical evaluation. The Moro response is missing or incomplete in the younger premature but should be readily obtained in any full-term normal baby. Its absence in a newborn may be due to a central nervous system disorder. Occasionally, an infant will display the Moro reflex on the first day, but this is followed by greatly diminished intensity of the response during the ensuing weeks, possibly because of birth injury or general muscular weakness. Occasionally cerebral edema or other factors may cause the reflex to be absent on the first day and gradually develop during the following 4 days. In some cases of cerebral hemorrhage, the reflex may be present the first day, disappear, and return slowly after the 6th day. These variations point to the value of public health nurses following up infants who have been discharged early from the hospital after delivery. Asymmetry of response may occasionally be noted in normal full-term infants, but asymmetry usually suggests fracture of the clavicle or humerus, injury to the brachial plexus, or neonatal hemiplegia. Paine (1964) points out that a defective Moro, opisthotonos, and the setting-sun sign of the eyes (only the upper half of the iris showing above the lower lid) are the principal and probably indispensable clinical signs of kernicterus in the first week of life. Whenever such symptoms are noted, the need for medical attention is immediate and urgent.

Paine did not find persistence of the Moro reflex beyond the 6th month in any of the infants in his series who had homologous retardation of psychic and motordevelopment. But abnormal persistence was seen occasionally in the presence of spastic tetraparesis, and in one infant who subsequently developed athetosis. Touwen (1976) points out that it may be hard to differentiate the Moro reflex from a fright response occurring later in life. Nevertheless, the older child with a persistent Moro is at risk of having this resemblance overlooked. As an example, in teaching the child self-feeding, the sudden extension of the arms and opening of the hands, causing the spoon to fly off in one direction and perhaps the food in the other, may be interpreted by the caregiver or "behavior shaper" as due to volitional, maladaptive behavior. Or it may be ascribed to the possibility that the child is too retarded to understand what is expected of him. In fact, this behavior may be due to elicitation of the Moro by lack of ability to maintain the head erect so that it drops back unexpectedly, a sudden flash of sunlight on the spoon, or a loud noise or unexpected jostle of the chair or table. In the course of routine nursing functions, no matter how gently the infant is handled, the reflex will be elicited several times in any 24-hour period in a hospital nursery, during the appraisal and demonstration bath carried out in the home by the public health nurse, or during the infant's visits to a well-child conference. If the infant's limbs are free to move, the hospital nurse should be alert for the Moro response when she rolls the bassinet to display the infant at the nursery window or when she replaces the infant in the bassinet after changing the crib sheet. The public health nurse should look for the Moro reflex as she puts the infant down just before or after demonstrating how to bathe the infant. Extreme care should be exercised at all times in handling distressed or premature infants, and they should receive more constant and consistent medical surveillance. However, while feeding, when checking vital signs, and in other circumstances when the infant is subjected to slight movements, the nurse can observe if and when the Moro appears and the characteristics of the response. The Asymmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex Articles by Gesell (1938) and Gesell and Ames (1960) contain descriptions of the asymmetrical tonic neck reflex. These authors assert that it is present in practically all infants during the first 12 weeks of life, often spontaneously manifested by the quiescent baby in the supine position as

well as during general postural activity. The asymmetrical tonic neck reflex appears "when the infant, lying on the back, turns the head to one side or if the head is passively rotated to one side." The infant tends to assume a "fencing" position-with his face toward the extended arm, while the other arm flexes at the elbow. The lower limbs respond in a similar manner.

Asymmetrical tonic neck reflex Paine (1960), Prechtl and Beintema (1964), and Andre-Thomas et al. (1960) have pointed out, however, that there is no constant asymmetrical tonic neck pattern among newborns. The response tends to be most noticeable between 2 and 4 months of age, being replaced by symmetrical head and arm positions (when the baby is in supine position) by the time the infant is 5 or 6 months old. Paine (1964), Prechtl and Beintema (1964), and Vassella and Karlsson (1962) agree that, while the tonic neck pattern may be partially imposed on a normal infant by passive rotation of the head, this is not a consistent response. A study of 66 normal infants during their first year of life found that a few infants under 3 months of age could sustain the asymmetrical tonic neck pattern for more than 30 seconds, but none demonstrated an imposable, sustained response (Paine et al., 1964). The studies indicate that while the asymmetrical tonic neck posture may be apparent from time to time during the first few months of life, persistence of the response after the 7th month constitutes an index of suspicion. Responses that are completely obligatory or unusually strong on one side or the other deserve medical attention at any age.

A persistent asymmetrical tonic neck reflex is potentially a very handicapping disability. The child is prevented from seeing both hands simultaneously unless measures are instituted to position the head and hands in midline. The effort to bring food or any object to the mouth is also inhibited. The influence of the pattern on the legs obviously poses severe restriction on the ability to achieve standing and walking. Since the newborn needs gentle cleansing of the face, neck, and area around the ears several times in a 24-hour period, the nurse has many opportunities to watch for the asymmetrical tonic neck response as she rotates the head of the infant in supine to cleanse first one side of the face and then the other. An observant nurse can discern whether the asymmetrical tonic neck reflex is present, whether the response is stronger on one side than the other, and whether it is compulsory or persistent. If the body response seems dependent on the head position in serial observations of an infant over 6 months of age, the nurse should ascertain whether the reflex has persisted. Waving a bright toy first to the right and then to the left of the child is an effective way to elicit active rotation of the head. With young infants it is a bit easier to use a passive head rotation maneuver. Observation for the asymmetrical tonic neck reflex pattern provides opportunity for carefully examining the child's neck to note the possible presence of torticollis or webbing. A particularly short neck in relation to the rest of the body is also worth noting. Finally, it is of interest to note that the early and normal tendency of the infant to extend the "face arm" places the hand in an excellent position to be viewed without effort. Even during the first few days and weeks of life, many normal infants may be observed maintaining attentive eye contact for minutes at a time with the hand they are facing while in this position. "Learning" that the hand is there, at the end of the arm, is a first step toward later learning what can be done with a hand. The Neck-Righting Reflex As the asymmetrical tonic neck response is "lost," it is replaced with a neck-righting reflex, in which passive or active rotation of the head to one side is followed by rotation of the shoulders, trunk, and pelvis in the same direction. In the true neck-righting response, there is a momentary delay between the head rotation and the following of the shoulders, as opposed to the automatic, sudden, and complete body rotation in

immediate response to a passive turn of the head that may occur in some abnormal states.

Neck-righting reflex The nurse may observe the two-step righting response in the normal child of 1 or 2 years, as he voluntarily gets up to a sitting position from the supine. First, he turns the head, then the shoulders, trunk, and pelvis, before undertaking the more complicated series of maneuvers by which he rolls over and achieves sitting (and/or rises from the floor in the quadrupedal manner). Paine et al. (1964) found that the neck-righting reflex was obtainable in all normal infants by 10 months of age and was gradually covered up by voluntary activity, making the age of its disappearance difficult to gauge. However, they point out that a neckrighting reflex in which the response is much stronger with the head to one side than to the other is not seen in normal infants; nor should the response at any age be so completely invariable that the baby can be rolled over and over. Stereotyped reflexes of this type are considered pathologic and are often found in infants with cerebral palsy. It also is relevant to note that infants with low muscle tone (hypotonicity) or with considerable excess of tone (hypertonicity) and infants with an obligatory asymmetrical tonic neck reflex would be impeded from demonstrating a normal neck-righting reflex. Posture in Ventral Suspension and the Landau Reflex All normal neonates display some evidence of tone when suspended in the prone position. The nurse may observe this when the baby is turned to prone during the nursery admission cleansing procedure. Public health nurses may assess tone as they weigh and measure the baby at well-child clinics or while bathing the child at home. As the newborn infant is turned to prone, with the trunk or abdomen supported, the legs should be

flexed. While the head may sag below the horizontal and the spine be slightly convex, the infant should not be completely limp and collapse into an inverted U. As the baby becomes a little older, the head and spine are maintained in a more nearly horizontal plane. There is a gradual increase in the tendency to elevate the head as if to look up, while the spine remains straight. Still later, there is elevation of the head well above the horizontal and arching of the spine in a concave position. Paine et al. (1964) found that the head was above the horizontal in 55 percent of their series at 4 months and in 95 percent at 6 months. The spine was at least slightly concave in approximately half of the 8-month-olds, but concavity was noted universally at 10 months. Many physicians designate this posture, with the back slightly arched, as a "positive Landau" (Touwen, 1976). Dissolution of the reflex is difficult to ascertain since it is gradually covered up by struggling or other voluntary activity. The Landau reflex is tested in a different way by others. While holding the infant in ventral suspension with the head, spine, and legs extended, the nurse then passively flexes the head forward. The reflex is considered present if the whole body then flexes. The reflex may be seen as early as 3 to 4 months but should be present after 7 months of age. In general, the nurse will find that holding the infant in ventral suspension provides more useful information than elicitation of the Landau by means of passive flexion of the head. In any event, the nurse's report to the physicians should describe exactly what was done and the infant's response. Whatever the infant's age, his limp collapse into an inverted U when held in ventral suspension should be called to immediate medical attention. The Parachute Reflex and Optical Placing of the Hands There is a tendency to refer to the parachute reflex when the behaviors being elicited and the reactions being described are actually those associated with the optical placing reaction of the hands. Touwen (1976) calls attention to and describes the difference between the two. In each instance, the infant is held in vertical suspension and suddenly lowered toward a flat surface. The normal positive response is a forward extension of both arms and dorsiflexion of the infant's hands during the movement. The difference between the two is that, in the optical placing reaction, the infant is permitted to see where he is going. This response may be noted as early as 3 months of age. In the true test for the parachute response, the maneuver is the same but the child's visual attention is first attracted to a bright toy displayed in front of and a little

above him and he is then suddenly plunged downward. Under these circumstances the parachute response may not be seen until about 6 or even 9 months of age. Touwen (1976) suggests that the earlier appearance of the positive response, when the child can anticipate visually that he is going down to a flat surface, illustrates the reinforcing effect of visual on vestibular input. Since the older infant tends to smile or chuckle under anticipatory circumstances but may be frightened when unexpectedly plunged, the former is usually the method of choice by the nurse in eliciting the presence of the reflex. If the child is plunged sideward as well as downward to the flat surface, the influence of the optical factors is reduced. Under these circumstances, partial response may be noted as early as 3 months. The complete response begins a little later; it will be noted in most infants by 9 months and in all normal infants by 12 months (Paine et al., 1964). In any event, the nurse should describe in her report exactly the way in which the parachute was elicited. An asymmetrical or absent response warrants medical appraisal.

Parachute reflex

Public health nurses are alerted to watch fathers at play with their children, as the game of "so high" or "airplane" may provide the opportunities to observe for the presence and character of the parachute reflex, as well as for extensor tone in ventral suspension. Nurses who have developed a warm rapport with the child and family may themselves play with the infant in this fashion, since most infants respond with great glee.

Palmar grasp AND Planter grasp "Palmar and Plantar Grasp Palmar and plantar grasp are strong automatic reflexes in full-term newborns. They are elicited by the observer placing a finger firmly in the child's palm or at the base of the child's toes. The palmar grasp response weakens as the hand becomes less continuously fisted, merging, sometime after 2 months, into the voluntary ability to release an object held in the hand. The plantar response disappears at about 8 or 9 months, though it may persist during sleep for a while thereafter. Possible abnormality may be suspected in asymmetry of response. While there is a tendency to fisting in the neonate, this should not be evident at all times. Serial observation of infants in the nursery should reveal relaxation of both hands at some point, usually during or right after feeding, or perhaps when asleep. These appraisals provide additional opportunities for detecting abnormalities of color such as cyanosis of the extremities, edema, simian palm crease (a straight line rather than an M-shape across the palm), and possible malformations of the hands and feet. Persistent edema of the feet is always worth noting, particularly if occurring in a

female child, as it may signal the presence of a chromosomal abnormality (X. 0. Turner's syndrome).

Simian palm crease Traction Response Physicians test the traction response by placing the infant in supine, then drawing him up by the hands to a sitting position. Normally, assistance by the shoulder muscles can be felt and seen. The newborn's head lags behind and drops forward suddenly when the upright posture is reached. Even in the newborn period, however, there should be sufficient head control to bring it back upright, and greater control is expected with age. The nurse in testing the neonate may gently raise the infant from supine in this way, in order to note the presence, absence, or asymmetry of response; but she should avoid reaching the midline point, which causes the head to drop forward suddenly. Supporting Reaction The supporting reaction is elicited by holding the infant vertically and allowing his feet to make firm contact with a table top or other firm surface. The "standing" posture includes some flexion of the hip and knee. Automatic stepping may also be observed when the newborn is inclined forward while being supported in this position. During the first 4 months of life, the crouching position gradually diminishes; this is followed by increase in support, so that normal infants will usually support a substantial propor- tion of their weight by 10 months (Paine, 1964).

Supporting reaction and stepping In this supported standing position, it is to be expected that a few infants will stand on their toes from time to time or occasionally cross or "scissor" their legs. However, consistent standing on the tips of the toes or scissoring of the legs after 4 months of age may be considered an index of suspicion warranting medical attention. A club foot or a deformity at the knee or hip may also become apparent while the supporting reaction is being appraised. By the age of 6 months, the supporting reaction is less easily demonstrable, and by 10 or 11 months, it is difficult to distinguish from voluntary standing.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Basic Reflex PatternsDocumento12 pagineBasic Reflex PatternsRalph Ryan TolentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Infant ReflexesDocumento2 pagineInfant ReflexesJose Raphael Delos SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Primitive ReflexesDocumento3 paginePrimitive ReflexesMio Navarro0% (1)

- Primitive ReflexesDocumento6 paginePrimitive ReflexesMarikit2012100% (1)

- Babinski & Parachute Reflex PPT Group 3 Bsn2aDocumento23 pagineBabinski & Parachute Reflex PPT Group 3 Bsn2aPaula AbadNessuna valutazione finora

- Babkin Palmomental ReflexTextDocumento3 pagineBabkin Palmomental ReflexTextdankopsNessuna valutazione finora

- Physical Development of Infants and Toddlers: Prepared By: Cedrick A. Caintic & WalocDocumento15 paginePhysical Development of Infants and Toddlers: Prepared By: Cedrick A. Caintic & WalocMildred Gonzales SumalinogNessuna valutazione finora

- Pediatric Case Tutorial For Suspected Cerebral PalsyDocumento35 paginePediatric Case Tutorial For Suspected Cerebral PalsySecret AgentNessuna valutazione finora

- A Field Guide to Sensory Motor Integration: The Foundation for LearningDa EverandA Field Guide to Sensory Motor Integration: The Foundation for LearningNessuna valutazione finora

- Cerebral Palsy Road Map:: What To Expect As Your Child GrowsDocumento40 pagineCerebral Palsy Road Map:: What To Expect As Your Child GrowsSergio Curtean100% (1)

- Cerebral Palsy: Fauziah Rudhiati, M.Kep., Ns - Sp.Kep - AnDocumento16 pagineCerebral Palsy: Fauziah Rudhiati, M.Kep., Ns - Sp.Kep - AnPopi NurmalasariNessuna valutazione finora

- OT Relevance RMTDocumento12 pagineOT Relevance RMTFredy RamoneNessuna valutazione finora

- Application of Facilitatory Approaches in Developmental DysarthriaDocumento22 pagineApplication of Facilitatory Approaches in Developmental Dysarthriakeihoina keihoinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cerebral Palsy Info SheetDocumento3 pagineCerebral Palsy Info Sheetapi-263996400100% (1)

- Help Your Class to Learn: Effective perceptual movement programs for classroomsDa EverandHelp Your Class to Learn: Effective perceptual movement programs for classroomsNessuna valutazione finora

- Infant ReflexesDocumento41 pagineInfant ReflexesamwriteaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Neurological Study of Newborn Infants: Clinics in Developmental Medicine, No. 28Da EverandA Neurological Study of Newborn Infants: Clinics in Developmental Medicine, No. 28Nessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction to Cerebral Palsy: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and TreatmentDocumento23 pagineIntroduction to Cerebral Palsy: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and TreatmentVenkata Nagaraj Mummadisetty100% (1)

- Cerebral Palsy: Signs and CausesDocumento2 pagineCerebral Palsy: Signs and CausesAhmad Rais DahyarNessuna valutazione finora

- Process of Motor DevelopmentDocumento33 pagineProcess of Motor Developmentmohitnet1327Nessuna valutazione finora

- Three Dimensions of Learning: A Blueprint for Learning from the Womb to the SchoolDa EverandThree Dimensions of Learning: A Blueprint for Learning from the Womb to the SchoolValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (1)

- Motor MildstonesDocumento13 pagineMotor MildstonesVaio Wolff AbendrothNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Motor ExaminationDocumento2 pagineOral Motor ExaminationJershon YongNessuna valutazione finora

- Masgutova Neurosensorimotor Integration MethodDocumento14 pagineMasgutova Neurosensorimotor Integration MethodristeacristiNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Parent-Delivered Action Observation Therapy On Upper Limb Function in Unilateral Cerebral PalsyDocumento40 pagineEffect of Parent-Delivered Action Observation Therapy On Upper Limb Function in Unilateral Cerebral PalsyNovaria Puspita SamudraNessuna valutazione finora

- Kernicterus, (Bilirubin Encephalopathy) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsDa EverandKernicterus, (Bilirubin Encephalopathy) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNessuna valutazione finora

- Developmental Assessment For Pediatric ResidentsDocumento89 pagineDevelopmental Assessment For Pediatric ResidentsDuncan89100% (1)

- Early Identification and Treatment Techniques in Babies WithDocumento47 pagineEarly Identification and Treatment Techniques in Babies WithDr.GK. JeyakumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Integrating ReflexesDocumento2 pagineIntegrating ReflexesAna G. VelascoNessuna valutazione finora

- Tummy Time ToolsDocumento6 pagineTummy Time ToolsflokaiserNessuna valutazione finora

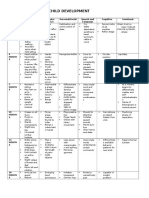

- Developmental Milestones (Complete)Documento14 pagineDevelopmental Milestones (Complete)KIARA VENICE DELGADONessuna valutazione finora

- Growth and DevelopmentDocumento2 pagineGrowth and DevelopmentCharmaine Vergara - GementizaNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Cerebral PalsyDocumento6 pagineWhat Is Cerebral PalsyAriel BarcelonaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cerebral Palsy (CP)Documento16 pagineCerebral Palsy (CP)Divija ChowdaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Sensory Integration ModuleDocumento48 pagineSensory Integration ModuleMadhu sudarshan ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Cerebral PalsyDocumento31 pagineCerebral Palsyfeby1992100% (1)

- Behavioural Problems in ChildhoodDocumento19 pagineBehavioural Problems in ChildhoodSai SanjeevNessuna valutazione finora

- Mixed Cerebral PalsyDocumento12 pagineMixed Cerebral Palsynishu_dhirNessuna valutazione finora

- Sensory Integration Therapy - Key AspectsDocumento16 pagineSensory Integration Therapy - Key AspectsAbd ALRahman100% (1)

- PD Sensory Room TrainingDocumento35 paginePD Sensory Room Trainingapi-393264699Nessuna valutazione finora

- Do You See? We play to get out of visual inattentionDa EverandDo You See? We play to get out of visual inattentionNessuna valutazione finora

- Assess Screen Tools 2Documento17 pagineAssess Screen Tools 2hashem111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sensory History QuestionnaireDocumento6 pagineSensory History Questionnaireİpek OMUR100% (1)

- Neurological Assessment in the First Two Years of LifeDa EverandNeurological Assessment in the First Two Years of LifeGiovanni CioniNessuna valutazione finora

- NEUROMUSCULAR DISEASES IN CHILDRENDocumento40 pagineNEUROMUSCULAR DISEASES IN CHILDRENSven OrdanzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Milestones in Child DevelopmentDocumento3 pagineMilestones in Child DevelopmentEva BellaNessuna valutazione finora

- My Child Without Limits - Cerebral PalsyDocumento46 pagineMy Child Without Limits - Cerebral PalsyBernard Owusu100% (1)

- Rood Approach Muscle RehabilitationDocumento33 pagineRood Approach Muscle RehabilitationCedricFernandez100% (1)

- Movement Difficulties in Developmental Disorders: Practical Guidelines for Assessment and ManagementDa EverandMovement Difficulties in Developmental Disorders: Practical Guidelines for Assessment and ManagementNessuna valutazione finora

- Minimal Brain Dysfunction in ChildrenDocumento31 pagineMinimal Brain Dysfunction in ChildrenDAVIDBROS64Nessuna valutazione finora

- Primitive Reflex in Preterm BabiesDocumento5 paginePrimitive Reflex in Preterm BabiesAmirul Zakri IsmailNessuna valutazione finora

- Primitive Reflexes and How They Affect PerformanceDocumento3 paginePrimitive Reflexes and How They Affect Performancemohitnet1327100% (1)

- Aca - 1Documento28 pagineAca - 1Aparna LVNessuna valutazione finora

- Developmental Milestones Motor Development - Peds Rev 2010Documento13 pagineDevelopmental Milestones Motor Development - Peds Rev 2010Carolina SanchezNessuna valutazione finora

- Hyper-Salivation, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsDa EverandHyper-Salivation, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNessuna valutazione finora

- Neurodevelopmental AssessmentDocumento11 pagineNeurodevelopmental AssessmentReem SaNessuna valutazione finora

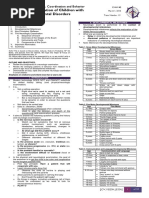

- Neurologic Evaluation of Children With Neurodevelopmental DisordersDocumento10 pagineNeurologic Evaluation of Children With Neurodevelopmental DisordersAthan AntonioNessuna valutazione finora

- The Neurological Examination of the Child with Minor Neurological DysfunctionDa EverandThe Neurological Examination of the Child with Minor Neurological DysfunctionNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing Neuromotor Readiness for Learning: The INPP Developmental Screening Test and School Intervention ProgrammeDa EverandAssessing Neuromotor Readiness for Learning: The INPP Developmental Screening Test and School Intervention ProgrammeValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Obstetric AnesthesiaDocumento440 pagineObstetric Anesthesiamonir61100% (1)

- Claim Form for Outpatient & Dental BenefitsDocumento1 paginaClaim Form for Outpatient & Dental BenefitsYiki TanNessuna valutazione finora

- Uterinefibroids 130120064643 Phpapp02Documento73 pagineUterinefibroids 130120064643 Phpapp02Tharun KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis and Management of Tumor Lysis SyndromeDocumento5 pagineDiagnosis and Management of Tumor Lysis SyndromeAndikhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Stacy Holton cv2014Documento2 pagineStacy Holton cv2014api-258404386Nessuna valutazione finora

- Section - 028 - Edentulous Histology - Tissue ConditioningDocumento13 pagineSection - 028 - Edentulous Histology - Tissue ConditioningDentist HereNessuna valutazione finora

- Malposition & MalpresentationDocumento36 pagineMalposition & MalpresentationN. Siva0% (1)

- Endometrial Hyperplasia: by Dr. Mervat AliDocumento48 pagineEndometrial Hyperplasia: by Dr. Mervat AliAsh AmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Pelvic Inflammatory DiseaseDocumento8 paginePelvic Inflammatory DiseaseAndyan Adlu Prasetyaji0% (1)

- 6 Hysterectomy/TAHBSO Nursing Care Plans: Low Self-EsteemDocumento5 pagine6 Hysterectomy/TAHBSO Nursing Care Plans: Low Self-Esteemonlyone_unik0% (1)

- NigerJClinPract205622-1531061 041510Documento7 pagineNigerJClinPract205622-1531061 041510Gusti Aridewo HutagaolNessuna valutazione finora

- The GWAC Critical Care Chronicle 6-14Documento5 pagineThe GWAC Critical Care Chronicle 6-14gwacaacnNessuna valutazione finora

- ContentServer - Asp 8Documento41 pagineContentServer - Asp 8mutiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pedo Tooth AnomaliesDocumento5 paginePedo Tooth Anomalieszuperzilch1676Nessuna valutazione finora

- Going Under Chapter SamplerDocumento28 pagineGoing Under Chapter SamplerAllen & UnwinNessuna valutazione finora

- English ProficiencyDocumento3 pagineEnglish ProficiencySultan AlexandruNessuna valutazione finora

- Pediatric Vital Signs Reference Chart PedsCasesDocumento1 paginaPediatric Vital Signs Reference Chart PedsCasesAghnia NafilaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 PPT Bioethics Lecture N1Documento44 pagine1 PPT Bioethics Lecture N1h.a.r.ade.v.ierNessuna valutazione finora

- Mindful Motherhood Yoga PosesDocumento4 pagineMindful Motherhood Yoga PosesredtinboxNessuna valutazione finora

- Arju 5Documento3 pagineArju 5arjumardi azrahNessuna valutazione finora

- The Rol of ParamedicsDocumento7 pagineThe Rol of ParamedicsJean ColqueNessuna valutazione finora

- Principles and Interpretation of CardiotocographyDocumento9 paginePrinciples and Interpretation of CardiotocographyCKNessuna valutazione finora

- NCPDocumento10 pagineNCPAnonymous AzknDcNn0% (1)

- Echobasics, Sys FXNDocumento5 pagineEchobasics, Sys FXNJing CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Record WikipediaDocumento4 pagineMedical Record WikipediaRisma KurniaNessuna valutazione finora

- DentinDocumento43 pagineDentinHari PriyaNessuna valutazione finora

- CPT PCM NHSNDocumento307 pagineCPT PCM NHSNYrvon RafaNessuna valutazione finora

- Handle Technique: Instruments and AccessoriesDocumento3 pagineHandle Technique: Instruments and AccessoriesMonette Guden CuaNessuna valutazione finora

- PCODDocumento76 paginePCODShreyance Parakh100% (1)

- Performance Improvement Team Worksheet (Focus-Pdca) Doc2Documento4 paginePerformance Improvement Team Worksheet (Focus-Pdca) Doc2api-283388869Nessuna valutazione finora