Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

In The News Selective Prosecution

Caricato da

jafernandTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

In The News Selective Prosecution

Caricato da

jafernandCopyright:

Formati disponibili

In the News: Selective Prosecution

Posted on March 16, 2011 by Philbert E. Varona One of the issues highlighted by the recent charges of corruption leveled against for er !"P #hief of $taff and #abinet $ecretary !ngelo %. &eyes 'follo(ing (hich he chose to end his life by his o(n hand) is the ris* of being sub+ected to selective and alicious prosecution by one,s political ene ies. $o e -uarters have ta*en the vie( that it (as anifestly unfair for $ecretary &eyes to have been sub+ected to intense and hostile -uestioning by his political opponents before the $enate '(ith full edia coverage or .trial by publicity/). 0ased on (hat are reported to be so e of $ecretary &eyes, final (ords on this issue 'see lin* to a report by the Philippine #enter for 1nvestigative 2ournalis here), it appears that the assailed syste s and .traditions/ (ithin the !"P (ere e3tant at the ti e he +oined the service. $o e have theori4ed that there are other, ore po(erful persons behind the scenes (ho are far ore deserving of punish ent, but have anaged to evade prosecution due to their political connections. 1s selective prosecution a valid defense under Philippine la(5 %he case of Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Court of Appeals '6.&. 7o. 118922, : 2une 1886) is of so e guidance. 1n that case, the #o issioner of 1nternal &evenue filed a co plaint against "ortune %obacco #orporation and several of its officers for ta3 evasion. One of the defenses raised (as that the accused (ere being singled out for cri inal prosecution in a discri inatory fashion, thus violating the e-ual protection clause of the #onstitution. %he #ourt found that the prosecutors had e3cluded certain evidence that (ould have sho(n that other tobacco co panies had paid the ta3es on the sa e basis and in the sa e anner as had "ortune 'and yet, according to the accused, (ere not si ilarly charged (ith ta3 evasion). !ccording to the #ourt, this indicated that only "ortune (as singled out for prosecution. ;o(ever, the #ourt stopped short of a*ing a categorical state ent that selective prosecution is a valid defense, as there (ere other grounds on (hich the #ourt based its ac-uittal of "ortune and the other accused. 1n a separate opinion, 2ustice 0ellosillo dissented fro the a+ority,s finding that there (as selective prosecution of "ortune and the other accused. !ccording to 2ustice 0ellosillo, .<t=here is no sho(ing that < = #o issioner of 1nternal &evenue is not going after others (ho ay be suspected of being big ta3 evaders and that only <the accused= are being prosecuted, or even erely investigated, for ta3 evasion > <!=ssu ing ex hypothesi that other corporate anufacturers are guilty of using si ilar sche es for ta3 evasion, the proper re edy is not the dis issal of the co plaints against private respondents, but the prosecution of other si ilar evaders./ 2ustice 0ellosillo also pointed out that .in the absence of (illful or alicious prosecution, or so?called @selective prosecution,, the choice on (ho to prosecute ahead of the others belongs legiti ately, and rightly so, to the public prosecutors./ %he case of Drilon v. Court of Appeals '6.&. 7o. 106822, 20 !pril 2001) also sheds so e light on the issue. 1n Drilon 'involving a civil co plaint for da ages brought by $enator 2uan Ponce Enrile, based on the filing of cri inal charges against hi for .rebellion co ple3ed (ith urder

and frustrated urder,/ a cri e (hich the $upre e #ourt, in separate proceedings, had ruled non?e3istent), alicious prosecution (as defined as a cri inal prosecution, civil suit, or other legal proceeding instituted against another aliciously 'or other .i proper and sinister otives/) and (ithout probable cause. %he gist of the action is the putting of legal process in force, regularly, for the ere purpose of ve3ation or in+ury. 1n such a case, the victi of alicious prosecution ay clai da ages fro the prosecutor. 1n Drilon, the #ourt clarified that a civil clai for da ages based on alicious prosecution should be filed only after the accused shall have been ac-uitted, i.e., after the cri inal charges have been dis issed and it can be established that the prosecution (as in fact aliciously brought. !ccording to the #ourt, allo(ing a party to file a co plaint for alicious prosecution before his ac-uittal (ould stifle the prosecution of cri inal cases by the ere e3pediency of filing da age suits against the prosecutors. %he rule is ore clearly stated in the Anited $tates. 1n the case of U.S. v Christopher Lee Armstrong et al. 'B1C A$ :B6, 1 16 $.#t. 1:D0 <1886=) E (hich involved an allegation by the accused that they had been selected for prosecution on the basis of their race E the A.$. $upre e #ourt 'citing nu erous cases) noted that a selective prosecution clai is .not a defense on the erits to the cri inal charge itself, but an independent assertion that the prosecutor has brought the charge for reasons forbidden by the #onstitution./ %he A.$. #ourt noted that prosecutors retain .broad discretion/ to enforce cri inal la(s because they are designated by statute as the E3ecutive,s delegates to help hi discharge his constitutional responsibility to ensure that the la(s be .faithfully e3ecuted,/ and that the presu ption of regularity supports their prosecutorial decisions in the absence of clear evidence to the contrary. %hat said, the A.$. $upre e #ourt (ent on to note that a prosecutor,s discretion is nevertheless .sub+ect to constitutional constraints/ such as the e-ual protection clause, (hich re-uires that a decision (hether to prosecute ay not be based on .an un+ustifiable standard such as race, religion, or other arbitrary classification./ Fhere it is de onstrated that the ad inistration of a cri inal la( is .directed so e3clusively against a particular class of persons > (ith a ind so une-ual and oppressive,/ the syste of prosecution a ounts to .a practical denial/ of e-ual protection of the la(. %he A.$. #ourt cautioned, ho(ever, that courts should be hesitant to e3a ine a decision (hether to prosecute. %he #ourt noted that the factors usually considered in deciding (hether to prosecute E e.g., the strength of the case, the prosecution,s general deterrence value, the 6overn ent,s enforce ent priorities, and the case,s relationship to the 6overn ent,s overall enforce ent plan E ay not be (ithin a court,s co petence to evaluate. !dditionally 'citing reasons si ilar to those that (ould be noted by the Philippine $upre e #ourt in Drilon five years later), courts should note that .<e=3a ining the basis of a prosecution delays the cri inal proceeding, threatens to chill la( enforce ent by sub+ecting the prosecutor,s otives and decision a*ing to outside in-uiry, and ay under ine prosecutorial effectiveness by revealing the 6overn ent,s enforce ent policy./ %he re-uire ents for a selective prosecution clai dra( on .ordinary e-ual protection standards,/ i.e., the clai ant ust de onstrate that the prosecutorial policy .had a

discri inatory effect and that it (as otivated by a discri inatory purpose./ "or e3a ple, to establish a discri inatory effect in a race case, the clai ant ust sho( that si ilarly situated individuals of a different race (ere not prosecuted. 1n the Lee Armstrong case, the A.$. $upre e #ourt ruled that the accused failed to sho( that the govern ent chose not to prosecute those in si ilar situations, and dis issed their clai .

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 11 November 2013 CivilDocumento14 pagine11 November 2013 CiviljafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Belgica VS OchoaDocumento15 pagine1 Belgica VS OchoajafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Bar Tips by Atty. Joan de VeneciaDocumento1 paginaBar Tips by Atty. Joan de VeneciajafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- 2006 Civil LawDocumento4 pagine2006 Civil LawjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- 9 September 2013 Civil LawDocumento9 pagine9 September 2013 Civil LawjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- 2006 Criminal Law Bar ExamsDocumento4 pagine2006 Criminal Law Bar ExamsjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Rule 135 144Documento40 pagine5 Rule 135 144jafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 January 2014 Philippine Jurisprudence LexotericaDocumento15 pagine1 January 2014 Philippine Jurisprudence LexotericajafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Posted On - Posted In,, - : January 15, 2014 Civil Law Philippines - Cases Philippines - LawDocumento12 paginePosted On - Posted In,, - : January 15, 2014 Civil Law Philippines - Cases Philippines - LawjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 1997 Rules of Civil ProcedureDocumento128 pagine1 1997 Rules of Civil ProcedurejafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- A. Rafael C. Dinglasan Jr. vs. Hon. Court of Appeals, Et Al.Documento11 pagineA. Rafael C. Dinglasan Jr. vs. Hon. Court of Appeals, Et Al.jafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 June 2013 On Civil LawDocumento23 pagine6 June 2013 On Civil LawjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- July 2013 QaDocumento52 pagineJuly 2013 QajafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 1989 Rules On EvidenceDocumento22 pagine4 1989 Rules On EvidencejafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- The Office of The Court Administrator vs. Develyn GesulturaDocumento7 pagineThe Office of The Court Administrator vs. Develyn GesulturajafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Judicial Affidavit SampleDocumento5 pagineJudicial Affidavit SampleJo ParagguaNessuna valutazione finora

- rULE ON wRIT OF aMPARODocumento7 paginerULE ON wRIT OF aMPAROjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Deed of Sale Vs Equitable MortgageDocumento3 pagineDeed of Sale Vs Equitable MortgagejafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- cIV 2 2011 BARDocumento7 paginecIV 2 2011 BARjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Vinson B. Pineda vs. Atty. Clodualdo C. de Jesus, Et AlDocumento5 pagineVinson B. Pineda vs. Atty. Clodualdo C. de Jesus, Et AljafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- The Special Audit Team, Commission On Audit vs. Court of AppealsDocumento15 pagineThe Special Audit Team, Commission On Audit vs. Court of AppealsjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Zenaida D. Mendoza vs. HMS Credit Corporation, Et AlDocumento11 pagineZenaida D. Mendoza vs. HMS Credit Corporation, Et AljafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Vinson B. Pineda vs. Atty. Clodualdo C. de Jesus, Et AlDocumento5 pagineVinson B. Pineda vs. Atty. Clodualdo C. de Jesus, Et AljafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Wallem Maritime Services, Inc. vs. Ernesto C. TanawanDocumento11 pagineWallem Maritime Services, Inc. vs. Ernesto C. TanawanjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Teresita L. Salva vs. Flaviana M. ValleDocumento11 pagineTeresita L. Salva vs. Flaviana M. VallejafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- The Trust As A Way of Preventing The Sale of Property in SaeculaDocumento3 pagineThe Trust As A Way of Preventing The Sale of Property in SaeculajafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 July 2013 Civil LawDocumento33 pagine7 July 2013 Civil LawjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Use by Married Woman of Her Maiden Name in Her ReplacementDocumento3 pagineUse by Married Woman of Her Maiden Name in Her ReplacementjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- Use by Married Woman of Her Maiden Name in Her ReplacementDocumento3 pagineUse by Married Woman of Her Maiden Name in Her ReplacementjafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- The Trust As A Way of Preventing The Sale of Property in SaeculaDocumento3 pagineThe Trust As A Way of Preventing The Sale of Property in SaeculajafernandNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- People vs. Dacanay, 807 SCRA 130, November 07, 2016Documento15 paginePeople vs. Dacanay, 807 SCRA 130, November 07, 2016MIKHAELA DELA TORRENessuna valutazione finora

- Labay Vs SandiganbayanDocumento23 pagineLabay Vs SandiganbayanHazel NiñolasNessuna valutazione finora

- Barredo Vs VinaraoDocumento1 paginaBarredo Vs VinaraoIanLightPajaroNessuna valutazione finora

- Mix Cases UploadDocumento4 pagineMix Cases UploadLu CasNessuna valutazione finora

- Vawc Monthly Report 2019Documento2 pagineVawc Monthly Report 2019Santa Isabel Barangay100% (1)

- Stages of A Murder TrialDocumento7 pagineStages of A Murder TrialGautam KrishnaNessuna valutazione finora

- ACT Supreme Court: Bennett V DaleyDocumento17 pagineACT Supreme Court: Bennett V DaleyToby VueNessuna valutazione finora

- Bail Orders 23-04-2020Documento22 pagineBail Orders 23-04-2020Charan PujariNessuna valutazione finora

- Campaign For Fair Sentencing of Youth BriefDocumento26 pagineCampaign For Fair Sentencing of Youth BriefangelabergmanNessuna valutazione finora

- People vs. Ben RubioDocumento2 paginePeople vs. Ben Rubioclaudenson18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Case & Forwarding ReportDocumento2 pagineCase & Forwarding ReportMarti GregorioNessuna valutazione finora

- CRIMPRO Case DigestDocumento66 pagineCRIMPRO Case Digestericjoe bumagatNessuna valutazione finora

- Del Castillo vs. PeopleDocumento20 pagineDel Castillo vs. PeopleErwin SabornidoNessuna valutazione finora

- Arroyo-Berwin CaseDocumento2 pagineArroyo-Berwin CaseMichelle100% (2)

- Cybersex: Philippines Private InvestigatorsDocumento3 pagineCybersex: Philippines Private InvestigatorsCarson GarazaNessuna valutazione finora

- FBI SSA Transcribed Interview TranscriptDocumento65 pagineFBI SSA Transcribed Interview TranscriptJennifer Van LaarNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter To Lexington Police DepartmentDocumento4 pagineLetter To Lexington Police Departmentthe kingfishNessuna valutazione finora

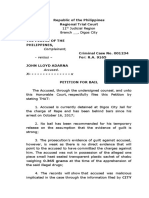

- Petition For Bail John LloydDocumento3 paginePetition For Bail John LloydRea RomeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Compilation of Laws and Other Issuances On Graft and CorruptionDocumento2 pagineCompilation of Laws and Other Issuances On Graft and CorruptionkellhermonsterNessuna valutazione finora

- Rosebud SIoux Tribe Criminal Offense CodeDocumento5 pagineRosebud SIoux Tribe Criminal Offense CodeOjinjintka NewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Crim 1 - Week 2Documento25 pagineCrim 1 - Week 2Ian PalmaNessuna valutazione finora

- File 79406Documento48 pagineFile 79406topo1974Nessuna valutazione finora

- ProceedingsDocumento1 paginaProceedingsnageshNessuna valutazione finora

- Theft Act 1978Documento5 pagineTheft Act 1978HanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Plea WithdrawalDocumento2 paginePlea Withdrawalangie_ahatNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Jesse Wright, JR., A.K.A. Jessie Wright, 392 F.3d 1269, 11th Cir. (2004)Documento15 pagineUnited States v. Jesse Wright, JR., A.K.A. Jessie Wright, 392 F.3d 1269, 11th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 177727. People vs. Cachuela & Ibanez, G.R. No. 191752Documento2 pagineG.R. No. 177727. People vs. Cachuela & Ibanez, G.R. No. 191752Thea BaltazarNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Muhtorov (Amicus Brief)Documento37 pagineUnited States v. Muhtorov (Amicus Brief)The Brennan Center for JusticeNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminal Law Last Minute TipsDocumento54 pagineCriminal Law Last Minute TipsPaula GasparNessuna valutazione finora

- Deposition of WitnessesDocumento1 paginaDeposition of WitnessesInnia PanteNessuna valutazione finora