Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Winiker v. Bell, Adverse Possession Appellate Brief

Caricato da

Richard VetsteinTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Winiker v. Bell, Adverse Possession Appellate Brief

Caricato da

Richard VetsteinCopyright:

Formati disponibili

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS Appeals Court

No. 2013-P-1008

MIDDLESEX, ss ________________________________ SAMUEL WINIKER AND FRANCES WINIKER Appellants v. KIMBERLY BELL Appellee ________________________________ ON APPEAL FROM A JUDGMENT OF THE MIDDLESEX SUPERIOR COURT ________________________________ BRIEF OF THE APPELLEE, KIMBERLY BELL ________________________________ Richard D. Vetstein, Esq. BBO # 637681 Vetstein Law Group, P.C. 945 Concord Street Framingham, MA 01701 (508) 620-5352 rvetstein@vetsteinlawgroup.com

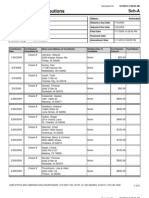

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ISSUES PRESENTED STATEMENT OF THE CASE STATEMENT OF FACTS SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ARGUMENT I. II. The Standard Of Review On Appeal The Trial Courts Findings of Fact Were Amply Supported By the Evidence and Not Clearly Erroneous, and Its Rulings Were Correct Under Massachusetts Adverse Possession Jurisprudence A. B. The Elements of Adverse Possession iii 1 1 3 15 15 16

16 20

The Trial Court Correctly Found That The Winikers Failed To Establish The Precise Area Of Adverse Possession. 21 The Trial Courts Finding That The Winikers Failed To Make Actual Use Of The Disputed Area Was Neither Clearly Erroneous Nor Legally Incorrect 25 The Trial Courts Finding That The Winikers Failed Prove Exclusive Use Was Neither Clearly Erroneous Nor Legally Incorrect 30 The Trial Court Correctly Concluded That the Winikers Did Not Adversely Possess The Bell Property Continuously For Twenty Years 34

C.

D.

E.

III. The Trial Court Did Not Abuse Its Discretion In Allowing Juan Ortegas Testimony 37

ii

IV.

The Winikers Brief Does Not Rise To The Level Of Acceptable Appellate Argument. This Appeal Is Frivolous

39 40 42

V.

CONCLUSION CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE ADDENDUM

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES Avery v. Steele, 414 Mass. 450 (1993) ............... 38 Barboza v. McLeod, 447 Mass. 468 (2006) ............. 15 Boston Edison Co. v. Brookline Realty & Investment Corp., 10 Mass. App. Ct. 63 (1980)................. 36 Boothroyd v. Bogarty, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 (2007) . 29 Brandao v. DoCanto, 80 Mass. App. Ct. 151 (2011). . 29 Conte v. Marine Lumber Co., Inc., 66 Mass. App. Ct. 505 (2006)......................................... 26 Collins v. Cabral, 348 Mass. 797 (1965). . . . . . .25 Custody of Eleanor, 414 Mass. 795 (1993) ............ 31 Demoulas v. Demoulas Super Markets, Inc., 424 Mass. 501 (1997). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15, 17 Foot v. Bauman, 333 Mass. 214 (1955). . . . . . . . 29 G.E.B. v. S.R.W., 422 Mass. 158 (1996) .............. 35 Goddard v. Dupree, 322 Mass. 247 (1948). . . . . . .16 Guardianship of Brandon, 424 Mass. 482 (1997) ....... 36 Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. 450 (1949) ............. 17 In re Sharis, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 839 (2013) .......... 31 Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 (1992) . 15, 17, 18, 29 Kershaw v. Zecchini, 342 Mass. 318 (1961) . . . . . 25 LaChance v. First Natl Bank & Trust Co., 301 Mass. 488 (1938)......................................... 25 Lawrence v. Concord, 439 Mass. 416 (2003) .. 17, 19, 25, 29 iii

Lee v. Mt. Ivy Press, L.P., 63 Mass. App. Ct. 538 (2005)............................................. 35 MacDonald v. McGillvary, 35 Mass. App. Ct. 902 (1993) ........................................... 17, 19, 29 Marlow v. New Bedford, 369 Mass. 501 (1976) ......... 15 Masa Builders, Inc. v. Hanson, 30 Mass. App. Ct. 930 (1991)............................................. 23 Masciocchi v. Utenis, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 1121 (2009) . 20 Masters v. Khuri, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 467 (2004) ...... 35 Mendonca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323 (1968)......................................... 19, 25 New England Canteen Serv., Inc. v. Ashley, 372 Mass. 671. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16 Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 (1993) .. 18, 19, 22, 24, 25, 29, 30, 32 Poirier v. Plymouth, 374 Mass. 206 (1978) ........... 32 Pugatch v. Stoloff, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 536 (1996) 19, 28 Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 (1964) ............... 17 Shaw v. Solari, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 151 (1979) ..... 19, 24 Stone v. Perkins, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 265 (2003) .. 21, 24 Tinker v. Bessel, 213 Mass. 74, 76 (1912) ....... 20, 21 Totman v. Malloy, 413 Mass. 143, 145 (2000). . . . .24 T.W. Nickerson, Inc., v. Fleet Nat. Bank, 456 Mass. 562 (2010). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17 United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364 (1948)......................................... 15

iv

STATUTES G. L. c. 231, 119 ................................. 37 G.L. c. 260, 21 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33 RULES Mass. R. App. P. 16 (e) ............................. 39 Mass. R. App. P. 25 ................................. 40 Mass. R. Civ. P. 52 (a) ............................. 15 Mass. R. Civ. P. 61 ................................. 34 TREATISES 3 Am.Jur.2d Adverse Possession 294 (2002) ......... 20 C.J.S. Adverse Possession 261 (2003) .............. 20

ISSUES PRESENTED I. Whether the trial judges findings of fact

and rulings of law after a bench trial that the appellants failed to meet their high burden of proving adverse possession was clearly erroneous and legally correct. II. Whether the trial court abused his

discretion in allowing a former owner of the subject property to testify, where the witness was disclosed pretrial, with his testimony fully disclosed in an affidavit filed in the case, and the appellants had ample opportunity to cross-examine him using that affidavit. III. Whether the appellants appellate brief rises to the level of acceptable appellate argument. IV. Whether this appeal is frivolous under Mass.

R. App. P. 25. STATEMENT OF THE CASE On March 9, 2009, the Appellant, Samuel Winiker commenced this action in the Middlesex Superior Court, claiming adverse possession over a portion of the abutting property of the Appellee, Kimberly Bell (Bell), on Norfolk Street in Holliston, Massachusetts. (A. 1-8). On April 7, 2009, Bell 1

filed an answer and counterclaim, which sought an permanent injunction ordering Winiker to remove an encroaching retaining wall and driveway from Bells property. (A. 2, 9-12).

On August 25, 2009, Winiker filed an assented to motion to amend his complaint to correct a misnomer, and on September 10, 2009, the Court (Billings, J.) allowed the motion, so that that the Appellants were properly named as Samuel Winiker and Frances Winiker (the Winikers). (A. 2, 17-18).

On March 24, 2011, the parties filed a joint pretrial memorandum. (A. 19-22). It disclosed Juan

Ortega of Florida, who previously owned the Bell property, as a witness for Bell. (A. 21).

On August 6-9, 2012, the Court (Henry, J.) presided over a jury-waived trial over four days during which nine witnesses testified. (A. 3). On

the last day of trial, the trial judge took a view of the properties. (A. 99-113). Both parties filed requests for findings of fact and rulings of law. (A. 3, 23-79, 80-90).

On November 5, 2012, the trial court issued a Memorandum of Decision and Order After Jury-Waived Trial, which ultimately found and ruled that the 2

plaintiffs have not proven by a preponderance of the credible evidence that they adversely possess the disputed portion of the Bell property. (A. 91-103).

Additionally, the lower court ordered the Winikers to remove any portion of their driveway and retaining wall which encroaches on the property of Ms. Bell. (A. 103). On November 7, 2012, the Court entered (A. 104).

Judgment on Finding of the Court.

On November 30, 2012, the Winikers filed a timely Notice of Appeal. (A. 4). On June 27, 2013, the

Appeals Court issued a Notice of Entry. STATEMENT OF FACTS In May of 1964, Samuel Winiker, an experienced real estate professional1, purchased a lot slightly over two acres on Norfolk Street in Holliston, Massachusetts. (Tr. Ex. 1, 2). In 1964, Mr. Winiker

subdivided the land into two buildable lots, designated as Lot X and Lot Y on a recorded plan. (Tr. Ex. 3). Lot Y was already improved with a home; Lot X

was unimproved and suitable for singe family development. (Id.). The Winikers built a home for

themselves on Lot X which is now numbered as 505 Norfolk Street (hereinafter, Winiker Property). (A.

1

(Tr. 381-83). 3

91, 1).

Lot Y is now the property owned by Ms. Bell

and is numbered 523 Norfolk Street (hereinafter, Bell Property). (A. 91, 1).

The Winikers have lived at the Winiker Property for approximately 45 years since the late 1960s. (Tr.305). The Bell Property has had seven sets of They were

owners, five of whom testified at trial.

John and Janice McDevitt, Juan Ortega, Kathleen Carter, James Jackson, and Ms. Bell. (A. 92). The area claimed by the Winikers by adverse possession is an approximately 2,616 square feet pieshaped area along the common boundary line between the Winiker Property and the Bell Property, as shown on a plot plan admitted as Trial Exhibit 14 (hereinafter, Disputed Area). The plot plan was drawn up in 2011

based on Mr. Winikers instructions to the surveyor. (Tr. 439). Mr. Winiker told the surveyor to plot a

line 30 feet into the rear of the Bell Property, then extend that line out straight at an angle to Norfolk Street, to correspond to where he claimed to have mowed the lawn. (Id.). In support of their adverse possession claim, the Winikers claimed to have undertaken various activities within the Disputed Area, such as planting trees, 4

maintaining a garden or berry patch, mowing the grass, and paving a driveway over a small portion of the Bell Property. The trial judge was faced with weighing the

testimony of the current and former owners of the Bell Property with the conflicting and often inconsistent testimony from the Winikers themselves. Tree Planting In support of their claimed adverse use, the Winikers alleged they planted several trees within the Disputed Area. However, as the trial judge observed,

Francis Winiker gave inconsistent testimony compared to her deposition as to when she planted those trees. (T. 144-46, 149). Likewise, Samuel Winiker at 77,

suffered from major lack of recall as to when those trees were allegedly planted. (A. 93). Mr. Winiker

was unable to positively identify one such maple tree on an old photograph of his children sitting on a vehicle dating back to 1972 or on an aerial blowup of the properties used at trial. (Tr.394-98).2 Accordingly, the trial judge discredited the Winikers testimony, and found that they had not proven by a

Mr. Winiker could not even positively identify any of his three kids in the old photograph. (T.380). Neither was he able to remember how many years he has been married. (T. 305, 380). 5

preponderance of the evidence that they planted trees in the Disputed Area. (A.93). Garden/Berry Patch As evidence of adverse use, the Winikers claimed to have maintained a garden and berry patch within the Disputed Area. Again, the trial judge was faced with

contradictory and conflicting testimony on this issue. Under cross-examination, Mrs. Winiker was unable to show exactly where this garden was located in relation to the Disputed Area, and testified inconsistently about the exact dates it was in existence. (Tr.17578). Her husband testified in his deposition that the

garden was installed in the 1990s some 20 years after his wifes assertion and at trial he could not say for sure exactly when the garden was in existence. (Tr. 414-16). With the garden no longer in existence,

the Winikers failed to offer a survey or soil analysis to prove where the alleged garden was located.3 (Tr. 177-78). Moreover, the former owners of the Bell

Property during this time, Juan Ortega, and John and Janice McDevitt, testified that Mrs. Winiker did not have a garden or berry patch on the Disputed Area.

According to Mrs. Winiker, the garden was removed in the late 1980s after she saw a snake. (Tr. 177). 6

(T.107-08; 125-26; 299-300).

As the trial judge

observed from taking a view, such a garden would have been obvious on the land. A.93. Accepting Mr.

Ortegas and the McDevitts' testimony as more credible than the Winikers, the trial court found that Winikers failed to establish that the garden was present within the Disputed Area for the requisite 20-year adverse possession period. (A.94).4 Lawn Mowing As evidence of adverse use, the Winikers claimed to have mowed the Disputed Area for 40+ years. There

was, again, much conflicting testimony on this issue as well as evidence of overlapping mowing by the former owners of the Bell Property. Between the 1960s to the late 1980s, the portion of the Disputed Area closest to Norfolk Street was covered by a dense grove of tall pine trees under which there were layers of pine needles and dirt, which rendered that area unmowable. (Tr.87-88, 91,

Indeed, the Winikers concede this point in their brief: Although the gardening at issue did not [sic] span the entire twenty-year period, it serves as evidence of the Winikers use of the property during a significant period of time. Winiker Brief at 14. 7

287-88, 495-97; A.92).5

Only the more open back area

of the Disputed Area was suitable for mowing. While the trial judge credited Mr. Winikers testimony that he mowed a portion of the Disputed Area towards the back yard area, he also accepted the testimony from all of the testifying prior owners of the Bell Property that they, too, mowed the same general area. John McDevitt, who lived at the Bell

Property from 1977 1983, mowed the back yard area, as it was not demarcated or fenced in. (Tr. 289-93). Mr. Ortega also mowed the same back yard area and specifically by the large maple tree which the Winikers claimed to have planted on the Disputed Area. (Tr. 90-91). Likewise, James Jackson, who resided at

the Bell Property from 1992 to 1998, mowed the same portion of the Disputed Area in the back area, which he characterized as shared and an open lawn area. (Tr. 499-500). Mr. Jackson mowed this area despite

the fact that Mr. Winiker may have mowed the same

For example, James Jackson testified that there was a cluster of pine trees somewhere between 60-80 feet tall, which shed layers and layers of pine needles. (Tr. 495-96). Mr. Jackson also removed up to five of these tall pine trees between the properties and within the Disputed Area, which opened up the previously dense area. (Tr. 497-98). 8

area, thereby creating what he described as an overlap of mowing. (Tr.507-08). Kathleen Carter, who owned the Bell Property between 1986 1992, likewise mowed portions of her back yard area within the Disputed Area. (Tr.266). James Jackson, owner of the Bell Property between 1992 1998, also mowed the same general area. (Tr. 499500, 504-05). Ultimately, given the conflicting testimony, the trial judge found that Mr. Winiker could not establish the exact area over which he mowed and that he mowed the Disputed Area to the exclusion of the owners of the Bell Property. (Tr. 441; A. 93, 11).6 There was

no clear cut delineation of where the property line was and there was no fence or wall between the two properties. (Tr. 400-01; A. 93, 11). Garage Project In 1988, the Winikers started a detached garage and driveway project ultimately resulting in the encroachment that is the genesis of this lawsuit. project took several years to complete, with final town inspections for the 2 story garage completed on

6

The

By way of example, when Mr. Winiker was shown a photograph of the property, he could not point out exactly where he mowed the lawn area. (Tr.441). 9

October 22, 1991. (Tr. Ex. 10).

The trial court found

that the Winikers occasionally stored construction materials on the Disputed Area during the construction, but such use was temporary. (A.95). Mr. Winiker designed the garage with a peculiar jag-edge to accommodate the boundary line shared with the Bell property. Tr. Ex. 16C). (Tr. Ex. 10 (building designs),

The trial judge found that the

nonconventional design demonstrated that Mr. Winiker was fully aware of the location of the lot line. (A.95). The garage project included a new driveway

and retaining wall which encroaches upon the Bell Property, the total area of which is approximately 250 square feet. (Tr. Ex. 14, A.95). encroaching aspect of the project. This was the only The completion of

the encroaching retaining wall and driveway came sometime after the Fall of 1991 and most likely in 1993-94 time-frame since Mr. Winiker did the work himself over the years. (Tr.431-32). Again, Mr.

Winiker went ahead with the encroaching work knowing where the lot line was, as the trial court found. (A.95). During the construction of the garage project, Mr. Winiker approached Kathleen Carter and asked her 10

if she was willing to sell him some of her land on the side property line, within the Disputed Area. (Tr.26769). The sale was never consummated. (Id.).

Use of Disputed Area by the Bell Property Owners There was quite a bit of evidence at trial that the former owners of the Bell Property also used and maintained the unenclosed Disputed Area. As referenced above, all of the former owners of the Bell Property testified they mowed the lawn within the Disputed Area, with no objection from the Winikers. Mr. Ortega measured off the lot lines

himself using his deed and cleared brush from the land, including within the Disputed Area. (Tr. 70, 7682, 88-89). Mr. Ortega also landscaped, raked leaves

and stacked firewood within the Disputed Area, with no objection from the Winikers. (Tr. 89-92, 107). The

stack of firewood remained on the Disputed Area even after Mr. Ortega sold the property to Mrs. Carter. (Tr.267). Mr. Ortega, who is of Puerto Rican descent,

also enjoyed at least two large family pig roast cookouts on his property. (Tr.93, 101-03). He and

his guests utilized the Disputed Area for walking about and volleyball, and seeking some alone time on a rock along the property line within the Disputed Area. 11

(Id.).

Mr. Ortega knocked on the Winikers door to

invite them to the pig roasts, but they did not respond. (Id.).

In addition to lawn mowing and yard work, James Jackson used the Disputed Area occasionally for cookouts, Frisbee and ball games. 05). (Tr. 499-500, 504-

Mr. Jackson also removed some pine trees in the

front portion of the Disputed Area along Norfolk Street. (Tr.497). Again, the Winikers never objected

to Mr. Jackson about using the Disputed Area or otherwise excluded him. (Tr.503-05).

In 1998, Ms. Bell put in dirt, arborvitae plantings and bushes within the Disputed Area after moving in. (Tr.567-71). She also mowed the grass

portions of the Disputed Area in the rear along the Winiker Property and near Norfolk Street. (Id.). Bell also cut through the Disputed Area and the Winiker Property to walk her dog on the way to nearby Lake Winthrop and Stoddard Park. (Tr.641). In 2002, Ms. Bell moved out of state, and she asked Mr. Winiker if he would mow her lawn which he did. (Tr.574-75). In 2007, Ms. Bell again asked Mr. Winiker to mow her lawn which he agreed to do. (A.95). Ms.

12

Bell Surveys Her Property and Installs Fence In April 2008, Ms. Bell commissioned a survey of her property and ran a string along the shared property line with the Winikers. (Tr.586, 592). The

survey showed that a portion the Winikers driveway and retaining wall encroached onto Bells property. Ms. Bell planted a row of Alberta spruce trees in May 2008 along the newly disclosed lot line, while the Winikers were away in Florida. (Id., Tr. Ex. 16-K). When the Winikers returned from Florida, Francis Winiker approached Ms. Bell, scolding her that shed better get those spruce off of there. (Tr.595). Winikers then approached Ms. Bell several times to secure an easement from Ms. Bell. (Tr.595-603). When The

Ms. Bell changed her mind about granting an easement, Mrs. Winiker barged into Ms. Bells home on a Sunday, threatening her that Mr. Winiker had a real estate brokers license and that Ms. Bell better give them what they want. (Tr. 603). Mrs. Winiker told Ms.

Bell that they had already consulted an attorney and if they didnt give them what they want, they were going to sue. (Id.). Ms. Bell felt that the Winikers were trying to intimidate and bully her. (Id.).

13

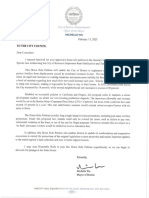

Ms. Bell then delivered a letter dated June 14, 2008 to the Winikers which the Winikers received. (Trial Ex. 13). The letter states, in part:

I wanted to take this opportunity to thank you for honoring my request of mowing my lawn during the entire 2007 mowing season while my house was vacant, as I was trying to move back home to Holliston.You did a good job, and your presence on my property is no longer required or wanted. Next, I wanted to thank you for respecting our mutual property line as indicated by the surveyor stakes and string that were installed in March of this year by GLM of Holliston. Additionally, I wanted to inform you of the new fence that I would like to install along part of our common property lineThe fence will then accommodate your driveway and portion of your stonewall which is currently encroaching on my property. There was no response to this letter by the Winikers. (Tr.607). On August 8, 2008, Ms. Bell installed a fence along the property line (within the Disputed Area), with a jag to accommodate the encroaching driveway and retaining wall, and that fence remains in the same location and configuration today. (Tr.607-09, Tr. Ex. 16E-G, 17). From that point forward, the Winikers

have been effectively excluded from using the Disputed Area. (Tr.608-09).

14

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT The Winikers adverse possession claim fails for four fatal reasons, all amply supported by the evidence and not clearly erroneous: The Winikers failed to establish the precise area over which they claimed adverse possession. See infra at 20-24. The Winikers claimed uses of the Disputed Area did not satisfy the actual use element of adverse possession. See infra at 24-29. See

The Winikers use was not exclusive. infra at 29-33.

The Winikers uses of the Disputed Area, even if credited, did not span an entire, consecutive 20 year period as required by G.L. c. 260, 21. See infra at 33-36.

The Trial Court did not abuse its discretion in allowing the testimony of Juan Ortega where his expected testimony was disclosed pretrial and the Winikers cross examination was not hampered in the least bit. See infra at 36-38.

The Winikers brief fails to rise to the acceptable level of appellate argument as it contains numerous, critical statements of fact and of the trial 15

testimony without any reference to, and often unsupported by, the trial transcript. See infra at 3840. Lastly, the Winikers appeal is frivolous as there is no reasonable expectation of reversal given the deference given to the Trial Courts findings of fact and his well-reasoned Memorandum of Decision. See infra at 40-42. ARGUMENT I. THE STANDARD OF REVIEW ON APPEAL. The appellate review of a bench trial is a twostep analysis, with the judges findings of fact given considerable deference, while his rulings of law are tested for legal error. Findings of fact shall not be Mass. R. Civ. A

set aside unless clearly erroneous.

P. 52 (a), as amended, 423 Mass. 1402 (1996).

finding is clearly erroneous when although there is evidence to support it, the reviewing court on the entire evidence is left with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been committed. Marlow v. New Bedford, 369 Mass. 501, 508 (1976), quoting United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395 (1948). The appellants have the burden

to show that a finding of fact is clearly erroneous. 16

First Pa. Mtge. Trust v. Dorchester Sav. Bank, 395 Mass. 614, 621622, 481 N.E.2d 1132 (1985). In applying the clearly erroneous standard, rule 52(a) requires that due regard shall be given to the opportunity of the trial court to judge the credibility of the witnesses. Demoulas v. Demoulas Super Markets, Inc., 424 Mass. 501, 509-510 (1997). The trial judge, who has a firsthand view of the presentation of evidence, is in the best position to judge the weight and credibility of the evidence. New England Canteen Serv., Inc. v. Ashley, 372 Mass. 671, 675 (1977). The judge's advantage in weighing

the testimony is particularly evident in a case (like this one) involving conflicting testimony, one in which widely differing inferences could be drawn from the evidence, and the drawing of inferences cannot be separated from the evaluation of the testimony itself. Goddard v. Dupree, 322 Mass. 247, 248, 76 N.E.2d 643 (1948). As a consequence, the appellate court does

not review questions of fact found by the judge, where such findings are supported on any reasonable view of the evidence, including all rational inferences of which it was susceptible. T.L. Edwards, Inc. v. Fields, 371 Mass. 895, 896, 358 17

N.E.2d 768 (1976), quoting Bowers v. Hathaway, 337 Mass. 88, 89, 148 N.E.2d 265 (1958). So long as the

judge's account is plausible in light of the entire record, an appellate court should decline to reverse it. Demoulas, 424 Mass. at 509. Where there are two

permissible views of the evidence, the fact-finder's choice between them cannot be clearly erroneous. Gallagher v. Taylor, 26 Mass. App. Ct. 876, 881 (1989), quoting Anderson v. Bessemer, 470 U.S. 564, 573574 (1985). In contrast to the review of findings of fact, an appellate court reviews a trial judges rulings of law de novo, and must be ensured to be in compliance with the applicable legal standards.

T.W. Nickerson, Inc.

v. Fleet Nat. Bank, 456 Mass. 562, 569 (2010); Demoulas, supra at 510. When the judge's

conclusions are based on reasonable inferences from the evidence and are consistent with the findings, there is usually no error. Demoulas, supra, at 510.

18

II.

THE TRIAL COURTS FINDINGS OF FACT WERE AMPLY SUPPORTED BY THE EVIDENCE AND NOT CLEARLY ERRONEOUS, AND ITS RULINGS OF LAW WERE CORRECT UNDER MASSACHUSETTS ADVERSE POSSESSION JURISPRUDENCE. As is fairly typical of an adverse possession

case, the trial court presided over a factually intensive trial with much conflicting evidence, both testimonial and documentary. The trial court was

tasked with evaluating the credibility, scope and duration of the various uses claimed by the Winikers to establish adverse possession, balanced with the often conflicting testimony of the former owners of the Bell Property. An adverse possession trial such

as this is, in essence, a detailed investigation into the history of a small sliver of land a task ideal for a trial court, but much less so for a reviewing appellate court. As discussed infra, the Winikers

adverse possession claim failed for four fatal reasons, all amply supported by the evidence: The Winikers failed to establish the precise area over which they claimed adverse possession.

19

The Winikers claimed uses of the Disputed Area did not satisfy the actual use element of adverse possession.

The Winikers use was not exclusive The Winikers uses of the Disputed Area, even if credited, did not span an entire, consecutive 20 year period as required by G.L. c. 260, 21.

Each reason supports affirming the judgment, and combined they demonstrate the pervasive weaknesses of the Winikers claim. A. The Elements of Adverse Possession Title by adverse possession can be acquired only by proof of non-permissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for twenty years. Lawrence v. Concord, 439 Mass. 416, 421 (2003); Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619, 621-622 (1992); Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251, 262 (1964). Acquisition of title through adverse possession is a question of fact to be proved by the one asserting the title. The burden of proof extends to all of the Holmes v. Johnson, Accord

necessary elements of the claim.

324 Mass. 450, 453 (1949) (citations omitted).

MacDonald v. McGillvary, 35 Mass. App. Ct. 902, 903 20

(1993).

If any of these elements is left in doubt, Mendonca v. Cities

the claimant cannot prevail.

Serv. Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323, 326 (1968). B. The Trial Court Correctly Found That The Winikers Failed To Establish The Precise Area Of Adverse Possession. Before even stepping into the adverse possession batters box, the Winikers were stuck on the on-deck circle of not being able to establish the exact area over which they asserted adverse possession, as Bell argued below and the trial court ruled. This fatality

was caused by the Winikers over-reliance upon the perfectly drawn pie shaped disputed area drafted up for them by a surveyor. (Tr. Ex. 14). As previously

stated, Mr. Winiker had this plan drawn up by instructing his surveyor to plot a course 30 feet into the Bell Property and draw a straight line back to Norfolk Street to the so-called town tree on Norfolk Street. (Tr.319-20). As the trial court correctly

found and ruled, the Winikers various claimed uses did not match up to the disputed area shown on the plan. A centurys old requirement, a claimant of adverse possession must describe the land adversely possessed in an exact and definite matter. See Tinker 21

v. Bessel, 213 Mass. 74, 76 (1912); see also Masciocchi v. Utenis, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 1121 (2009), citing 3 Am.Jur.2d Adverse Possession 294, at 328 (2002). See also 2 C.J.S. Adverse Possession 261,

at 692 (2003) (A claimant of title by adverse possession must further show the extent of their possession, the exact property which was the subject of the claim of ownership). As the SJC held over 100

years ago, [t]he definite description [of adversely possessed land], which would be necessary for a valid grant, must be supplied from evidence of actual use. It must be explicit and not left to inference or implication. Tinker, 213 Mass. at 76. See also

Stone v. Perkins, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 265, 268 (2003) (in the analogous context of prescriptive easements, a claimant must show a definite location of the prescriptive easement on the servient property). The

rationale for this requirement, as the trial court noted during directed verdict arguments (Tr.487), is that the evidence must be sufficiently definite to support a description in the judgment upon which a metes and bounds measurement could be performed. See

Masa Builders, Inc. v. Hanson, 30 Mass. App. Ct. 930, 931 (1991). 22

The Court applied this long-standing legal standard to the facts, and concluded correctly that, [w]hile the plaintiffs have presented a plan which designates the portion of the Bell property which they are claiming by adverse possession, I do not accept that plan as being the area over which they did exert at least some control for some periods of time. 99). (A.

While the Winikers may have hoped the evidence

came in at trial consistent with the pie-shaped Disputed Area on Trial Exhibit 14, that is not how the evidence came in at all. For example, as the trial

court correctly found, the evidence of Mrs. Winikers claimed garden and berry patch was a moving target and not well delineated. She could not say for

certain exactly where the garden was located relative to the Disputed Area, and she conceded it was possible it was on her own property.7 Mrs. Winiker also changed

Mrs. Winiker testified as follows: Q. Okay. And its certainly a possibility that the garden was located wholly on your side of the property, isnt that right? A. Possibly. Q. Youre not really sure, as you sit here today, exactly where the garden is was, correct? A. I have a very good recollection of where it was. Q. Didnt you testify at your deposition that it was possible that the garden was on wholly on your side of the property? 23

the dates of when the garden was created between her deposition and trial. (Tr. 175-78). Her husbands

recollection was far worse, dating the mysterious garden in the 1990s, over 20 years after Mrs. Winiker claimed to have started it. (Tr. 414-16). And of

course, three former owners of the Bell Property testified that Mrs. Winiker did not have a garden at all. (T.107-08; 125-26; 299-300). The same fuzziness inflicted the Winikers evidence of lawn mowing. Because of the large cluster

of pine trees at the front portion of the Disputed Area near Norfolk Street, mowing a straight line in congruity with the Winikers pie-shaped depiction of the Disputed Area was impossible. Mr. Winikers best

case was that he mowed some portion of the Disputed Area in the rear backyard, however, there was abundant evidence that such use was not exclusive and that the former owners of the Bell Property mowed the same area. Instead of a perfectly drawn piece of pie, the evidence of the Winikers adverse use came in more like the family dog ate the pie, with pieces and A. When it was first put in, I thought it was on our side, but I found out later that it wasnt. (Tr.177). 24

crumbles left here and there in the pan.

The evidence

of adverse possession provided by the Winikers was insufficiently definite to support a description in the judgment upon which a metes and bounds measurement could be performed. See Masa Builders, Inc. v. The trial

Hanson, 30 Mass. App. Ct. 930, 931 (1991).

courts judgment can and should be affirmed on this basis alone. C. The Trial Courts Finding That The Winikers Failed To Make Actual Use Of The Disputed Area Was Not Clearly Erroneous and In Accord With Established Case Law.

In general, a person makes actual use of the property if they use, control, or make changes upon the land similar to the uses, controls, or changes that are usually and ordinarily associated with property ownership in the local area. Totman v.

Malloy, 413 Mass. 143, 145 (2000); Stone v. Perkins, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 265, 266 (2007). The test is the

degree of control exercised over the land by the possessors. (1979). Another important factor in the actual use analysis is whether the claimant made any permanent improvements upon the land for the requisite 20 year Shaw v. Solari, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 151, 156

25

period.

See Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551, For example, Massachusetts courts have

556 (1993).

deemed permanent improvements to consist of the building of stone walls, a septic system, or an actual house. LaChance v. First Natl. Bank & Trust Co. of

Greenfield, 301 Mass. 488, 491 (1938); Collins v.

Cabral, 348 Mass. 797, 797-798 (1965); Kershaw v. Zecchini, 342 Mass. 318, 320 (1961).

Improvements

that are not attached to the land and easily removable are not considered evidence of actual use. Mass. App. Ct. at 556. Noting that it was a close question (A.100) a judgment call by the trial judge to be given considerable deference the trial court considered all of the uses put forth by the Winikers but ultimately ruled, correctly, that they fell short of the high threshold of actual use. As the trial Peck, 34

court correctly found, the seasonal or sporadic use of the disputed property, in essence as a side yard, and the acts of mowing and tending a garden and a berry patch are insufficient to give the Winikers adverse possession of the property. (A. 101). This

finding is entirely consistent with the case law on actual use. See Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 26

551, 553-557 (1993) (claimant who mowed, used space for picnic table and lounge chairs, clotheslines, planting and maintaining trees for ten years, raking leaves, but who made no permanent improvements on the lot failed to prove actual use); Conte v. Marine Lumber Co., Inc., 66 Mass. App. Ct. 505, 509 (2006) (clearing trees, burying rubbish, planting rye grass, and digging loam could not suffice in intensity to qualify for adverse possession despite the lack of fencing for the construction of buildings). The trial courts finding that Mr. Winikers lawn mowing was merely seasonal and sporadic was not by any means clearly erroneous or legally incorrect. See Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 (1993) (seasonal lawn mowing for 24 years was not sufficient adverse or exclusive use); Marciano v. Peralta, 2008 WL 4266509, 2 (Mass. App. Ct.,2008) (holding that occasional,

seasonal lawn mowing did not satisfy the requirement of actual use). Indeed, if the occasional mowing of a

portion of a next door neighbors lawn is adverse possession, there would be meritorious adverse possession claims between neighbors from Weymouth to Salem and all points in between.

27

The same is true for the Winikers sporadic parking of vehicles, temporary storage of construction equipment or the seasonal piling up of snow. (Winiker Brief at 14). Mr. Winiker conceded that any storage

of construction materials was for a few months at a time during the projects, and he could not say for sure the actual duration of any such storage. (Tr.472-73). The trial judge did acknowledge that the

Winikers, occasionally used some of the property in question to park equipment and materials during the construction phase. (See A. 93, 9). He concluded

correctly, however, that the sporadic use of some of the disputed property for this purpose was not sufficient to establish ownership of the area. A. 101). See Peck, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 556. As for the plowing of snow, Mr. Winiker readily acknowledged that such use, by definition, was seasonal in that one can only plow snow when it snows, and that depended on the particular season. (Tr.475). During his discussion regarding snow plowing, Mr. Winiker could not provide an exact number of times that he plowed snow into the Disputed Area. (Tr.350). As for parking vehicles, the only place to park vehicles on the Disputed Area was on the new driveway 28 (See

which was not was completed until 1994-95.

With seven

garage bays for five vehicles,(Tr.222), it was no surprise that the Winikers conceded that they parked vehicles within the Disputed Area for no more than a few days at a time as needed. (Tr.44, 347).8 Even if

accepting arguendo that the parking of vehicles is sufficiently adverse use, it fell well short of the applicable 20 year period which ending in 2008 when Ms. Bell fenced in the property line.9 (Tr.403). Lastly, the Winikers did not make any permanent improvements to the land for the requisite 20 year period. The only possible improvement would have been

the encroaching driveway and retaining wall, but again, such use did not pass the 20 year threshold. At best, the driveway and wall began in 1992 but Ms. Bell clearly asserted her ownership by installing a fence in 2008, thereby leaving the period short by 4 years, as the trial court correctly found. (A.101).

On direct, Mr. Winiker testified that the parking of vehicles was as needed for an hour, overnight, maybe a couple of days, but you know, no more than an couple of days at a time. (Tr.347). 9 Mr. Ortega testified that he never observed the Winikers parking on the Disputed Area. (Tr. 108). 29

D.

The Trial Courts Finding That The Winikers Failed To Prove Exclusive Use Was Neither Clearly Erroneous Nor Legally Incorrect.

Proof of exclusive use is often the death-knell of adverse possession claimants, and it was here. Winikers were charged with the formidable task of proving that they excluded Ms. Bell and her predecessors in title and all other persons to the same extent that a true owner would have excluded them if it were his or her property. Lawrence v. Concord, The

439 Mass. 416, 421-2 (2003); Boothroyd v. Bogarty, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40, 44 (2007); Foot v. Bauman, 333 Mass. 214, 218 (1955). In the language of old English property law, such use must encompass a disseisin of the record owner. Peck, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 557.

Exclusive use most often takes the form of a fence, wall or other structure which physically shuts out anyone from gaining access into a disputed area. See, e.g., Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619, 621 (1992) (fence); MacDonald v. McGillvary, 35 Mass. App. Ct. 902, 903 (1993) (fence); Brandao v. DoCanto, 80

Mass. App. Ct. 151 (2011) (entire condominium building). The exclusivity requirement gives the

victim of possible adverse possession the opportunity to challenge the adverse use. See Lawrence v. Concord, 30

439 Mass. 416, 421 (2003).

After all, if a neighbor

sees a fence being installed on her property, the law says she should not sit on her property rights, lest an adverse possession claim ripens. In the same vein, shared or permissive use cannot be exclusive use as a matter of law. Peck, 54 Mass.

App. Ct. at 555-56; Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 421-2 (2003); Boothroy, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44. The Winikers acknowledged throughout their testimony that they never made any attempt to exclude their neighbors or anyone else from the Disputed Area. (Tr. 179-180, 196, 238-239). If fact, they seemed

proud of the fact that they were so welcoming in letting others come onto their property for ball games, to enjoy their garden, and back yard. The

Winikers never installed a fence or other barrier to entry. (Tr. 41, 52, 64). finally installed a fence. Indeed, it was Ms. Bell who There was never any

demarcation of the property line, until Ms. Bell had the property surveyed in 2008. By all accounts from

the trial testimony and the photographs admitted at trial, the Disputed Area was a fairly open side and back yard area with areas of pine and maple trees and lawn typical of any given suburban yard area in the 31

Commonwealth.

The failure to enclose or otherwise

shut out others from the adversely possessed area is almost always fatal to an adverse possession claim, and it is here. See Peck, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 557

The evidence further showed that the owners of the Bell Property made just as much, if not more, use of the Disputed Area, thereby refuting any claim of exclusivity. The trial court was well within its

right as the trier of fact to accept the testimony of Mr. McDevitt, Mr. Ortega, and Mr. Jackson as to their numerous activities on the Disputed Area, including mowing, stacking firewood clean up, removing brush, taking down trees, raking leaves, holding pig roasts and cookouts, playing games, etc.10 (A. 101). The

Winikers could not refute this testimony as they testified they hardly if ever interacted with their neighbors. The Winikers attack on Mr. Ortegas

credibility hardly warrants a response as it was

10

The Winikers contend that the trial courts factual finding that Mr. McDevitt went onto the disputed property . . . seems at odds with his actual testimony. (See Appellants Brief at 15). That is not correct. Mr. McDevitt testified that he mowed back to the end of what we - - of what our property was. (T. 289-293). This was the same area allegedly mowed by Mr. Winiker. As such, the Courts fact finding with regard to Mr. McDevitt is not clearly erroneous. 32

solely within the trial judges province and not shown to be clearly erroneous.11 The case of Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 (1993), rev. denied, is directly on point with this case and supports the trial courts judgment. In

Peck, this Court found no adverse possession although the claimant mowed the disputed area for over 20 years, used a picnic table and lounge chairs, set up three clotheslines, put in a rope swing and sandbox, built a henhouse, planted and cut down several trees, maintained compost and lumber piles, and rakes leaves

11

The Winikers contend that Mr. Ortegas testimony suffers from a number of difficulties, such as alleged problems with credibility, veracity, and undue influence. (See Appellants Brief at 15-17). These criticisms are, of course, the sole province of the trier of fact to evaluate. Moreover, the Winikers make an illogical attempt to undermine Mr. Ortegas testimony concerning his guests use of the Disputed Area, arguing that the rock that Mr. Ortegas guests sat on during his pig roasts is not even in the disputed area but exists directly on the property of the Winikers. (See Appellants Brief at 16). At trial, there was much disagreement over the location of this rock, with the Winikers trial counsel even urging the trial judge to dig around the rock during his view. (Tr.556-62). Recognizing the potential problems with such an archeological dig, the trial court thought better of it. In any event, even if the rock was on the Winiker side, it further weakens the Winikers exclusivity argument, as the only reasonable inference one could draw is that Mr. Ortegas guests could only reach the Winikers rock by walking to it over the disputed area. 33

and pruned trees on the disputed land.

Id. at 553-54.

This was not enough, the Court said, as there was no permanent fence or other structure shutting out others from the land. Passing, then, to the acts of the

present defendant on the land-the crux-we conclude that, taking even an indulgent view, he failed to carry his burden of proving his actual or exclusive use in the sense of the doctrine of adverse possession. Id. at 556.

Following Peck and the other jurisprudence considering exclusivity, the trial court correctly ruled that the plaintiffs failed to establish a disseisin of the other owners of the Bell property. (See A. 101). E. The Court Correctly Concluded That The Winikers Did Not Adversely Possess The Bell Property Continuously For Twenty Years.

The essential statutory requirement, a person claiming title by adverse possession must occupy the locus without the permission of the true owner, continuously for twenty years. Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 425. G.L. c. 260, 21;

Continuity of possession

is interrupted by acts of dominion by the owners consistent with their title of record. 354 Mass. at 326. 34 See Mendonca,

The trial court correctly found and ruled that there was no consecutive 20 year period in which the Winikers exclusively, actually and openly used the Disputed Area. Any adverse possession by the Winikers

starting from the time they occupied their property in the late 1960s was effectively stopped by the activities of the McDevitts beginning in 1977 when they purchased the property. (A.101). And the

activities of the Bell Property owners carried over into the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s with the numerous uses of the Disputed Area by Mr. Ortega, Mrs. Carter, the Jacksons and finally Ms. Bell. As discussed at

length above, the trial courts finding that Mrs. Winikers garden and berry patch did not last for the requisite twenty-year period was not clearly erroneous given the conflicting testimony on that issue. The trial court also correctly found that the activities surrounding the Winikers detached garage project did not run for 20 years. The trial record is

clear from the building permit application, plans and inspection records and Mr. Winikers own testimony that the only encroachment onto the Disputed Area came through the driveway and retaining wall which was completed, at the earliest in 1992, according to the 35

trial courts finding.12 (Tr. Ex. 10, Tr.431-32).13 Bell asserted her ownership of the Disputed Area in

Ms.

2008 by having her property surveyed and installing a fence. The adverse possession time period may be

broken by a challenge to the alleged adverse possession, re-entry onto the land or a legal action. Bucella v. Agrippino, 257 Mass. 483 (1926).14 Accordingly, the encroachment of the driveway and retaining wall lasted only 16 years, at best. Accordingly, the Court correctly concluded that, [t]here is no consecutive twenty year period in which the Winikers exclusively, actually, and adversely used the disputed portion of the Bell property.

12

(A. 101).

The Winikers brief contains what is, at best, an inartful misstatement, when it contends: That garage had a driveway and retaining wall which both in part intruded into the Disputed Property. (See Appellants Brief at 6). The record shows clearly that the garage is solely on the Winikers property. (Tr. Ex. 16, Tr. 339). In fact, that was the reason for the peculiar jag edge of the structure. Accordingly, the Winikers cannot legitimately argue that the garage intruded into the disputed area. 13 More accurately, Mr. Winiker completed the driveway and wall as late as 1993-94 according to his testimony. (Tr.431-32) 14 On April 7, 2009, Bell filed a counterclaim in this action seeking an injunction ordering the Winikers to remove the encroaching retaining wall and driveway from Bells property. (See. A. 10-11). Commencing a legal action against an adverse possessor interrupts a claim for adverse possession. See Pugatch, 41 Mass. App. Ct. at 544 n.10. 36

III. THE COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS DISCRETION IN ALLOWING THE TESTIMONY OF JUAN ORTEGA The trial courts judgment call to allow the testimony of Juan Ortega over the Winikers objection relating to pre-trial disclosure can only be overturned upon a showing of abuse of discretion. The conduct and scope of discovery is within the sound discretion of the judge ... [, and appellate courts will] not interfere with the judge's exercise of discretion in the absence of a showing of prejudicial error resulting from an abuse of discretion. Wilson v. Honeywell, Inc., 28 Mass. App.

Ct. 298, 303-304 (1990), citing Solimene v. B. Grauel & Co., 399 Mass. 790, 799, (1987). been made. Mr. Ortega was listed as a testifying witness on the Joint Pretrial Memorandum. (A.21). did not depose him, however. The Winikers No such showing has

As to pretrial

disclosure, Mr. Ortega submitted an affidavit during summary judgment proceedings which outlined his expected testimony. (Trial Ex. 18). Mr. Ortegas

trial testimony, specifically regarding measuring the lot lines, tracked his affidavit, as the trial judge noted during argument on the issue. (Tr.75). Despite

37

his claimed surprise by Mr. Ortegas testimony, the Winikers trial counsel used Ortegas affidavit extensively during his skilled cross-examination, and in fact offered it as an exhibit which the trial judge allowed. (Trial Ex. 18, A. 132-39). The Winikers If

cross examination was not hampered at all.

anything, it was enhanced by the detail provided in the affidavit. There was no surprise as Ortegas

testimony was entirely consistent with his affidavit which counsel had over a year before the trial. Accordingly, the Winikers have failed to show that the trial judge committed any abuse of discretion or that they were unduly prejudiced by Mr. Ortegas testimony. See Wilson v. Honeywell, Inc., 28 Mass. App. Ct. at 303-304 (ruling that trial judge was not required to exclude evidence despite claimed non-disclosure under Mass. R. Civ. P. 26); G.E.B. v. S.R.W., 422 Mass. 158, 169 (1996) (The burden is on . . . the proponent of the exclusion, to show that the trier of fact might have reached a different result if the ruling had been different.) Id. See G. L. c. 231, 119 (error in

admission of testimony must affect substantial rights proponent of objection).

38

IV.

THE WINIKERS BRIEF DOES NOT RISE TO THE LEVEL OF ACCEPTABLE APPELLATE ARGUMENT. The Winikers brief contains numerous, critical

statements of the fact and of the trial testimony without any reference to, and often unsupported by, the trial transcript. 10, 13-19.15 See Appellants Brief at 3, 6-

This type of appellate draftsmanship

makes an appellate review of a bench trial nearly impossible. It improperly puts the burden on this

Court and Bells counsel to cull through the trial transcript and determine whether the appellants statements are supported by the record and factually accurate. That is the job of the appellants counsel.

The Rules of Appellate Procedure provide that [n]o statement of a fact of a case shall be made in any part of the brief without an appropriate and accurate record reference. Mass. R. A. P. 16 (e).

References in the briefs to parts of the record reproduced in an appendix shall be to the pages of the appendix at which those parts appear, Mass. R. A. P.

15

For example, the Winikers claim, without record citation, the evidence in this case does not demonstrate a single parking of an automobile on the disputed property but a continued habit and pattern of conduct in doing so. Winiker Brief at 14. There was no such evidence adduced at trial of a habit or continued pattern of parking vehicles. 39

16 (e), as amended, 378 Mass. 940 (1979). Guardianship of Brandon, 424 Mass. 482, 497 n.22 (1997). See also Boston Edison Co. v. Brookline

Realty & Investment Corp., 10 Mass. App. Ct. 63, 69 (1980) (striking portions of brief not supported by record references). This Court should disregard all statements of fact and argument contained in the Winikers brief not supported by an appropriate and accurate record reference. Unfortunately, the Winikers Brief is

riddled with this poor practice. V. THIS APPEAL IS FRIVOLOUS. Pursuant to Mass. R. App. P. 25 and G. L. c. 211, 10, Bell respectfully moves for an award of her reasonable attorneys fees, and double costs, in connection with defending against the Winikers frivolous appeal. An appeal is frivolous when the

law is well settled, when there can be no reasonable expectation of a reversal. Mass. 450, 455 (1993). As counsel for Bell argued below, this was a very weak case of adverse possession, and now more so on appeal, given the deferential standard of review. This trial was conducted by a judge who carefully 40 Avery v. Steele, 414

listened to the trial testimony, asked questions, reviewed the trial exhibits and took a view of the property. The trial judge wrote a well reasoned 13

page Memorandum Decision in which he carefully outlined his findings of fact, noting where he credited the testimony of the Winikers or Ms. Bells witnesses. He recited the jurisprudence of adverse

possession law correctly, and his legal reasoning was sound. The Winikers case in chief consisted only of

themselves, and was riddled with inconsistencies, lack of recall and conflicting testimony. Once Ms. Bell

started putting on the former owners of the Bell Property, it was clear that the Winikers would be unable to prove all of the elements of adverse possession over the required 20 year period. not even close. Moreover, there was evidence that the Winikers used threats of litigation to intimidate and bully Ms. Bell. (Tr.603). When Ms. Bell refused to cave into It was

the Winikers demands, they brought this lawsuit, even though it was objectively very weak. Furthermore, as

with all claims of adverse possession, the Winikers claim has created a cloud on Ms. Bells title, and effectively makes it virtually impossible to sell. 41

Not a person of means, Ms. Bell has spent many thousands of dollars on attorneys fees defending this case through trial and appeal. On appeal, it is almost as if the Winikers counsel has mailed it in by filing a substandard brief, filled with misstatements of fact, a dearth of record citations, and legal arguments which have no likelihood of success. Ms. Bell feels that the

Winikers have taken this appeal in order to out-spend her and wear her down into submission. This is unfortunately one of those cases where this Court should seriously consider an award of appellate attorneys fees and double costs. Bell

moves for same, and requests an opportunity to submit an affidavit of attorneys fees and costs. CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, Bell requests that this Honorable Court affirm the judgment of the Superior Court, strike those portions of the Winikers brief are not supported by record references, and award her reasonable attorneys fees and double costs.

42

Respectfully submitted, Kimberly Bell, By her attorney,

_________________________________ Richard D. Vetstein, BBO #637681 Vetstein Law Group, P.C. 945 Concord Street Framingham, MA 01701 (508) 620-5352 rvetstein@vetsteinlawgroup.com Dated: December 2, 2013

43

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE I, Richard D. Vetstein, hereby certify, pursuant to Mass. R. A. P. 16 (k), that the Appellees brief complies with the rules of court that pertain to the filing of briefs, including, but not limited to: Mass. R. A. P. 16 (a)(6) (pertinent findings or memorandum of decision); Mass. R. A. P. 16 (e) (references to the record); Mass. R. A. P. 16 (f) (reproduction of statutes, rules, regulations); Mass. R. A. P. 16 (h) (length of briefs); Mass. R. A. P. 18 (appendix to the briefs); and Mass. R. A. P. 20 (form of briefs, appendices, and other papers).

_________________________________ Richard D. Vetstein, Esq.

ADDENDUM

ADDENDUM MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL LAWS Chapter 211, Section 10. interest. Frivolous appeals; costs and

If, upon the hearing of an appeal in any proceeding, it appears that the appeal is frivolous, immaterial or intended for delay, the court may, either upon motion of a party or of its own motion, award against the appellant double costs from the time when the appeal was taken and also interest from the same time at the rate of twelve per cent a year on any amount which has been found due for debt and damages, or which he has been ordered to pay, or for which judgment has been recovered against him, or may award any part of such additional costs and interest. Chapter 260, Section 21. Recovery of Land.

An action for the recovery of land shall be commenced, or an entry made thereon, only within twenty years after the right of action or of entry first accrued, or within twenty years after the demandant or the person making the entry, or those under whom they claim, have been seized or possessed of the premises; provided, however, that this section shall not bar an action by or on behalf of a nonprofit land conservation corporation or trust for the recovery of land or interests in land held for conservation, parks, recreation, water protection or wildlife protection purposes. MASSACHUSETTS RULES OF APPELLATE PROCEDURE Rule 16. Briefs.

(e) References in Briefs to the Record. References in the briefs to parts of the record reproduced in an appendix filed with a brief (see Rule 18(a)) shall be to the pages of the appendix at which those parts appear. If the appendix is prepared after the briefs are filed, references in the briefs to the record shall be made by one of the methods allowed by Rule 18(c). If the record is reproduced in accordance with 2

the provisions of Rule 18(f), or if references are made in the briefs to parts of the record not reproduced, the references shall be to the pages of the parts of the record involved; e.g., Answer p. 7, Motion for Judgment p. 2, Transcript p. 231. Intelligible abbreviations may be used. If reference is made to evidence the admissibility of which is in controversy, reference shall be made to the pages of the appendix or of the transcript at which the evidence was identified, offered, and received or rejected. No statement of a fact of the case shall be made in any part of the brief without an appropriate and accurate record reference. Rule 25. Damages for Delay.

If the appellate court shall determine that an appeal is frivolous, it may award just damages and single or double costs to the appellee, and such interest on the amount of the judgment as may be allowed by law. MASSACHUSETTS RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE Rule 52. Findings by the Court.

(a) Courts Other Than District Court: Effect. In all actions tried upon the facts without a jury, the court shall find the facts specially and state separately its conclusions of law thereon, and judgment shall be entered pursuant to Rule 58. Requests for findings are not necessary for purposes of review. Findings of fact shall not be set aside unless clearly erroneous, and due regard shall be given to the opportunity of the trial court to judge of the credibility of the witnesses. The findings of a master, to the extent that the court adopts them, shall be considered as the findings of the court. If an opinion or memorandum of decision is filed, it will be sufficient if the findings of fact and conclusions of law appear therein. Findings of fact and conclusions of law are unnecessary on decisions of motions under Rules 12 or 56 or any other motion except as provided in Rule 41(b)(2).

Rule 61.

Harmless Error.

No error in either the admission or the exclusion of evidence and no error or defect in any ruling or order or in anything done or omitted by the court or by any of the parties is ground for granting a new trial or for setting aside a verdict or for vacating, modifying or otherwise disturbing a judgment or order, unless refusal to take such action appears to the court inconsistent with substantial justice. The court at every stage of the proceeding must disregard any error or defect in the proceeding which does not affect the substantial rights of the parties.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Petition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413Da EverandPetition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413Nessuna valutazione finora

- Petition for Certiorari – Patent Case 01-438 - Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a)Da EverandPetition for Certiorari – Patent Case 01-438 - Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lighting the Way: Federal Courts, Civil Rights, and Public PolicyDa EverandLighting the Way: Federal Courts, Civil Rights, and Public PolicyNessuna valutazione finora

- Anti-SLAPP Law Modernized: The Uniform Public Expression Protection ActDa EverandAnti-SLAPP Law Modernized: The Uniform Public Expression Protection ActNessuna valutazione finora

- Motion To Quash - Cleaned Up-6Documento6 pagineMotion To Quash - Cleaned Up-6Joshua KarmelNessuna valutazione finora

- Swindled: If Government is ‘for the people’, Why is the King Wearing No Clothes?Da EverandSwindled: If Government is ‘for the people’, Why is the King Wearing No Clothes?Valutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- The Complete Guide to Planning Your Estate in North Carolina: A Step-by-Step Plan to Protect Your Assets, Limit Your Taxes, and Ensure Your Wishes are Fulfilled for North Carolina ResidentsDa EverandThe Complete Guide to Planning Your Estate in North Carolina: A Step-by-Step Plan to Protect Your Assets, Limit Your Taxes, and Ensure Your Wishes are Fulfilled for North Carolina ResidentsNessuna valutazione finora

- SERVICE PROCESS SUMMONSDocumento5 pagineSERVICE PROCESS SUMMONSemsulli26100% (1)

- Oregon v. Barry Joe Stull Motions January 22, 2020 FinalDocumento60 pagineOregon v. Barry Joe Stull Motions January 22, 2020 Finalmary engNessuna valutazione finora

- Regulatory Breakdown: The Crisis of Confidence in U.S. RegulationDa EverandRegulatory Breakdown: The Crisis of Confidence in U.S. RegulationNessuna valutazione finora

- 12-03-30 Microsoft Motion For Partial Summary Judgment Against MotorolaDocumento30 pagine12-03-30 Microsoft Motion For Partial Summary Judgment Against MotorolaFlorian Mueller100% (1)

- Civil Appellate Practice in the Minnesota Court of AppealsDa EverandCivil Appellate Practice in the Minnesota Court of AppealsValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Pleading IndexDocumento2 paginePleading Indexapi-518705643Nessuna valutazione finora

- Federal Tort Claims Act: Volume 1: Volume 1: Contemporary DecisionsDa EverandFederal Tort Claims Act: Volume 1: Volume 1: Contemporary DecisionsValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Garber Opposition To Motion For Summary JudgmentDocumento102 pagineGarber Opposition To Motion For Summary Judgmentngrow9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fire & Smoke: Government, Lawsuits, and the Rule of LawDa EverandFire & Smoke: Government, Lawsuits, and the Rule of LawNessuna valutazione finora

- 08-10-2016 ECF 1000 USA V DAVID FRY - Motion in Limine To Exclude HearsayDocumento10 pagine08-10-2016 ECF 1000 USA V DAVID FRY - Motion in Limine To Exclude HearsayJack RyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Individual FMLADocumento11 pagineIndividual FMLAMatthew Seth SarelsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Defendants Motion For Summary JudgmentDocumento18 pagineDefendants Motion For Summary JudgmentKenan FarrellNessuna valutazione finora

- Rules of Civil ProcedureDocumento160 pagineRules of Civil Procedurech0pperf100% (3)

- Brief of AppelleeDocumento48 pagineBrief of AppelleeSunlight FoundationNessuna valutazione finora

- Registration by Federation of State Medical Boards To Lobby For Federation of State Medical Boards (300307117)Documento2 pagineRegistration by Federation of State Medical Boards To Lobby For Federation of State Medical Boards (300307117)Sunlight FoundationNessuna valutazione finora

- CASE NO. Nos. 20-5928 United States Court of Appeals For The Sixth CircuitDocumento59 pagineCASE NO. Nos. 20-5928 United States Court of Appeals For The Sixth CircuitChrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Plaintiff Original PeitionDocumento7 paginePlaintiff Original PeitionmartincantuNessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence Outline Goodno (Spring 2013) : Exam: We Do NOT Need To Know Rule Numbers or Case Names I.PDocumento36 pagineEvidence Outline Goodno (Spring 2013) : Exam: We Do NOT Need To Know Rule Numbers or Case Names I.PzeebrooklynNessuna valutazione finora

- CriminalLawOutline PodgorDocumento19 pagineCriminalLawOutline PodgorjarabboNessuna valutazione finora

- Louis E. Wolfson and Elkin B. Gerbert v. Honorable Edmund L. Palmieri, United States District Judge For The Southern District of New York, 396 F.2d 121, 2d Cir. (1968)Documento7 pagineLouis E. Wolfson and Elkin B. Gerbert v. Honorable Edmund L. Palmieri, United States District Judge For The Southern District of New York, 396 F.2d 121, 2d Cir. (1968)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- EasyKnock v. Feldman and Feldman - Motion To DismissDocumento32 pagineEasyKnock v. Feldman and Feldman - Motion To DismissrichdebtNessuna valutazione finora

- Plaintiff's Response in Opposition To Defendants' Motion To AbateDocumento62 paginePlaintiff's Response in Opposition To Defendants' Motion To AbateHeather DobrottNessuna valutazione finora

- 131 Master Omnibus and JoinderDocumento172 pagine131 Master Omnibus and JoinderCole StuartNessuna valutazione finora

- Illinois Civil Procedure Code Section on Form of PleadingsDocumento6 pagineIllinois Civil Procedure Code Section on Form of Pleadingsjuliovargas6100% (1)

- Yale Law Professor Analyzes Restatement of ContractsDocumento26 pagineYale Law Professor Analyzes Restatement of ContractsDemetrius New ElNessuna valutazione finora

- Above the Law: Secret Deals, Political Fixes and Other Misadventures of the U.S. Department of JusticeDa EverandAbove the Law: Secret Deals, Political Fixes and Other Misadventures of the U.S. Department of JusticeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Four Mistakes: Avoiding the Legal Landmines that Lead to Business DisasterDa EverandThe Four Mistakes: Avoiding the Legal Landmines that Lead to Business DisasterValutazione: 1 su 5 stelle1/5 (1)

- United States District Court For The Western District of Texas San Antonio DivisionDocumento6 pagineUnited States District Court For The Western District of Texas San Antonio DivisionTexas Public RadioNessuna valutazione finora

- Baroni V Wells Fargo, Nationstar Et Al Motion To Amend With SACDocumento143 pagineBaroni V Wells Fargo, Nationstar Et Al Motion To Amend With SACDinSFLA100% (2)

- Davis EvidenceDocumento101 pagineDavis EvidenceKaren DulaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gatekeeper Orders in North Carolina Courts What When and How PDFDocumento4 pagineGatekeeper Orders in North Carolina Courts What When and How PDFnwg002Nessuna valutazione finora

- Citigroup's Motion To Dismiss Terra Firma's EMI LawsuitDocumento31 pagineCitigroup's Motion To Dismiss Terra Firma's EMI LawsuitDealBookNessuna valutazione finora

- Brief in Opposition To Trademark Injunction RequestsDocumento32 pagineBrief in Opposition To Trademark Injunction RequestsDaniel BallardNessuna valutazione finora

- Civilprocedure (With 20 General Civil Forms Oh)Documento434 pagineCivilprocedure (With 20 General Civil Forms Oh)cjNessuna valutazione finora

- ConsumerCreditManual NysDocumento83 pagineConsumerCreditManual NysGary LeeNessuna valutazione finora

- 20 08 12 Petition For ContemptDocumento39 pagine20 08 12 Petition For ContemptDanny ShapiroNessuna valutazione finora

- Federal Preliminary InjuctionDocumento10 pagineFederal Preliminary Injuctionapi-302391561100% (1)

- An Overview of Article 78 Practice and Procedure 05-21-09Documento81 pagineAn Overview of Article 78 Practice and Procedure 05-21-09test123456789123456789Nessuna valutazione finora

- Plaintiffs Response To Def's MTN To Quash & MTN For Protective OrderDocumento42 paginePlaintiffs Response To Def's MTN To Quash & MTN For Protective OrderBuddy FalconNessuna valutazione finora

- Winning with Financial Damages Experts: A Guide for LitigatorsDa EverandWinning with Financial Damages Experts: A Guide for LitigatorsNessuna valutazione finora

- Ann Karnofsky Landlord Tenant Court Ruling Central (Massachusetts) Housing CourtDocumento5 pagineAnn Karnofsky Landlord Tenant Court Ruling Central (Massachusetts) Housing CourtRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Court Hearing Transcript, 9/2/20, Baptiste v. Charles Baker, Governor of Massachusetts, Eviction MoratoriumDocumento68 pagineCourt Hearing Transcript, 9/2/20, Baptiste v. Charles Baker, Governor of Massachusetts, Eviction MoratoriumRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- October 7th: Was It A Pogrom?Documento17 pagineOctober 7th: Was It A Pogrom?Richard Vetstein100% (1)

- Mayor Wu Rent Control and Tenant Eviction Protection Revised 2-15-2023Documento4 pagineMayor Wu Rent Control and Tenant Eviction Protection Revised 2-15-2023Richard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Court Hearing Transcript, 9/1/20, Baptiste v. Charles Baker, Governor of Massachusetts, Eviction MoratoriumDocumento77 pagineCourt Hearing Transcript, 9/1/20, Baptiste v. Charles Baker, Governor of Massachusetts, Eviction MoratoriumRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Kaplan v. New England Paragliding Club Ruling On Preliminary InjunctionDocumento7 pagineKaplan v. New England Paragliding Club Ruling On Preliminary InjunctionRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Boston Eviction Moratorium Order On Motion To StayDocumento16 pagineBoston Eviction Moratorium Order On Motion To StayRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Tenczar v. Indian Pond Country Club, Inc., 491 Mass. 89 (Dec. 20, 2022)Documento35 pagineTenczar v. Indian Pond Country Club, Inc., 491 Mass. 89 (Dec. 20, 2022)Richard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Massachusetts Appeals Court Single Justice Ruling On Boston Eviction MoratoriumDocumento8 pagineMassachusetts Appeals Court Single Justice Ruling On Boston Eviction MoratoriumRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- CDC Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions To Prevent The Further Spread of Covid-19Documento17 pagineCDC Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions To Prevent The Further Spread of Covid-19Richard Vetstein100% (1)

- Lawsuit Avila v. Dr. Bisola Ojikutu, Boston Public Health Commission (City of Boston Eviction Moratorium)Documento28 pagineLawsuit Avila v. Dr. Bisola Ojikutu, Boston Public Health Commission (City of Boston Eviction Moratorium)Richard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- CDC Eviction Moratorium Emergency Order Federal RegisterDocumento6 pagineCDC Eviction Moratorium Emergency Order Federal RegisterRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Court Ruling On Boston Eviction MoratoriumDocumento15 pagineCourt Ruling On Boston Eviction MoratoriumRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Boston Public Health Commission Temporary Eviction Moratorium Order 8 31 21Documento3 pagineBoston Public Health Commission Temporary Eviction Moratorium Order 8 31 21Richard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- UMNV V Caffe Nero - Mot Partial SJ - 2084CV01493-BLS2Documento12 pagineUMNV V Caffe Nero - Mot Partial SJ - 2084CV01493-BLS2Richard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hill We Climb - Amanda Gorman, Inaugural Address January 20, 2021, National Youth Poet LaureateDocumento4 pagineThe Hill We Climb - Amanda Gorman, Inaugural Address January 20, 2021, National Youth Poet LaureateRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Amicus Curiae Submissions of Small Landlords, Challenge To Mass. Eviction Moratorium ActDocumento55 pagineAmicus Curiae Submissions of Small Landlords, Challenge To Mass. Eviction Moratorium ActRichard Vetstein0% (1)

- Judge Mark Wolf Opinion Preliminary Injunction Baptiste v. Kennealy, Massachusetts Eviction Moratorium 9.25.20Documento102 pagineJudge Mark Wolf Opinion Preliminary Injunction Baptiste v. Kennealy, Massachusetts Eviction Moratorium 9.25.20Richard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Superior Court Amicus Invitation, Matorin v. CommonwealthDocumento1 paginaSuperior Court Amicus Invitation, Matorin v. CommonwealthRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Memo Re. Preliminary Injunction Final 7.15.20 PDFDocumento35 pagineMemo Re. Preliminary Injunction Final 7.15.20 PDFRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Matorin v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts Decision On Preliminary InjunctionDocumento34 pagineMatorin v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts Decision On Preliminary InjunctionRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions To Prevent The Further Spread of COVID-19Documento37 pagineTemporary Halt in Residential Evictions To Prevent The Further Spread of COVID-19Kristina KoppeserNessuna valutazione finora

- First Amended Complaint, Federal Challenge To Massachusetts Eviction MoratoriumDocumento78 pagineFirst Amended Complaint, Federal Challenge To Massachusetts Eviction MoratoriumRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Single Justice Order of Transfer Matorin v. Chief JusticeDocumento3 pagineSingle Justice Order of Transfer Matorin v. Chief JusticeRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Massachusetts Virtual Remote Notarization Act For COVID-19 Emergency (Final Draft)Documento8 pagineMassachusetts Virtual Remote Notarization Act For COVID-19 Emergency (Final Draft)Richard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Matorin V Chief Justice, SJC Petition Challenge Mass. COVID-19 Eviction MoratoriumDocumento119 pagineMatorin V Chief Justice, SJC Petition Challenge Mass. COVID-19 Eviction MoratoriumRichard Vetstein50% (2)

- Massachusetts Act Providing For Moratorium On Evictions and Foreclosures During COVID-19 EmergencyDocumento8 pagineMassachusetts Act Providing For Moratorium On Evictions and Foreclosures During COVID-19 EmergencyRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Signed Order Re Alarms Inspections PDFDocumento2 pagineSigned Order Re Alarms Inspections PDFRichard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Massachusetts Act Relative To Remote Notarization During COVID-19 State of Emergency.Documento5 pagineMassachusetts Act Relative To Remote Notarization During COVID-19 State of Emergency.Richard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- John Giuca 440.10 Reply Brief January 30 2020Documento27 pagineJohn Giuca 440.10 Reply Brief January 30 2020Richard VetsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Monitoring in The WorkplaceDocumento26 pagineMonitoring in The WorkplaceBerliana SetyawatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Moonlight MazeDocumento35 pagineMoonlight MazeAudiophile DenNessuna valutazione finora

- Ready To Administer Survey Questionnaire. LARIVA PRINT EditedDocumento2 pagineReady To Administer Survey Questionnaire. LARIVA PRINT EditedCharvelyn Camarillo RabagoNessuna valutazione finora

- Pale Canon 5Documento41 paginePale Canon 5Nemei SantiagoNessuna valutazione finora

- Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth, 524 U.S. 742 (1998)Documento26 pagineBurlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth, 524 U.S. 742 (1998)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Tribunal Report NandigramDocumento97 pagineTribunal Report Nandigramsupriyo9277100% (1)

- StatconDocumento94 pagineStatconAngeloReyesSoNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Republic V OrbecidoDocumento2 pagine3 Republic V OrbecidoQueentystica ZayasNessuna valutazione finora

- James Walter P. Capili, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippines and Shirley Tismo Capili, RespondentsDocumento10 pagineJames Walter P. Capili, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippines and Shirley Tismo Capili, RespondentsMoniqueLeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Khap PanchayatsDocumento22 pagineKhap Panchayatsdikshu mukerjeeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Occulted Powers of The British ConstitutionDocumento14 pagineThe Occulted Powers of The British ConstitutionSteven HendryNessuna valutazione finora

- 050 SJS v. DDB 570 SCRA 410Documento15 pagine050 SJS v. DDB 570 SCRA 410JNessuna valutazione finora

- SSS Vs AguasDocumento3 pagineSSS Vs AguasPhi SalvadorNessuna valutazione finora

- IWDA PAC - 9761 - A - ContributionsDocumento2 pagineIWDA PAC - 9761 - A - ContributionsZach EdwardsNessuna valutazione finora

- Colorado v. Evan Hannibal: Motion To SuppressDocumento4 pagineColorado v. Evan Hannibal: Motion To SuppressMichael_Roberts2019Nessuna valutazione finora

- Role of UN in Bridging The Gap BetweenDocumento12 pagineRole of UN in Bridging The Gap BetweenDEEPAK GROVER100% (1)

- Preamble: Read Republic Act 8491Documento3 paginePreamble: Read Republic Act 8491Junjie FuentesNessuna valutazione finora

- Court Convicts Couple of Illegal Drug PossessionDocumento13 pagineCourt Convicts Couple of Illegal Drug PossessioncjadapNessuna valutazione finora

- A Sociological Perspective On Dowry System in IndiaDocumento11 pagineA Sociological Perspective On Dowry System in IndiaSanchari MohantyNessuna valutazione finora

- Mackinac Center Exposed: Who's Running Michigan?Documento19 pagineMackinac Center Exposed: Who's Running Michigan?progressmichiganNessuna valutazione finora

- Fourth Amendment Rights in SchoolsDocumento37 pagineFourth Amendment Rights in SchoolsJeremiahgibson100% (1)