Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

BASSAM TIBI Islamism Peace Maghreb

Caricato da

ahmadsiraziCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

BASSAM TIBI Islamism Peace Maghreb

Caricato da

ahmadsiraziCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Islamism, Peace, and the Maghrib

Islamism, Peace, and the Maghrib

by Bassam Tibi

Islamism in the contemporary Maghrib is the subject of this lecture. The fact that it is delivered at an Israeli university by a Sunni Arab of Damascusone descended from one of that citys oldest and most notable familiesbegs explanation. My personal point of departure is my commitment to peace, through acknowledging the place of Israel in the Middle East, and the right of the Jewish people to sovereignty on the grounds of mutuality. This acknowledgment is clearly related to the topic of this lecture, given the impediment posed by Islamism to the peace process. And since peace in international relations is democratic peace, this raises the related question of the compatibility of Islamism and democracy.

Islamism and Democratic Peace

Let me be unequivocal from the very beginning: as a reformist Muslim, I believe in the compatibility of Islam, understood as morality, with modern democracy. Islamism, in contrast, is not a religionbased morality, but is rather a concept of political order, which is not a democratic one. I operate on the assumption that a democratic peace is a guarantee for non-belligerent conflict resolution, through which democracies negotiate with each other, rather than wage war. In this context, the question is whether divine orders states based on divine law, such as the Islamic sharia or the Jewish halachacould live in peace with one another. Numerous opinion polls demonstrate that secular Israelis are more favorable to the peace process than non-secular ones. My findings support a similar assessment for the Arab states. To be sure, peace is

Bassam Tibi is Professor of International Relations at Gttingen University. His lecture was delivered as the Sixteenth Annual George A. Kaller Lecture, on 12 January 2000.

Bassam Tibi

so urgent in the Middle East that we cannot wait until preconditions of secularization and democratization are achieved. But in realistic terms, we need to ask which political systems are more favorable to peace than others. My working hypothesis is that an Islamic state as envisaged by the Islamists cannot accept Israel as an equal partner for Arab Muslims. In contrast, the traditional Islam-based monarchy in Morocco has been highly supportive of the idea of peace with Israel, as the legacy of the late King Hassan II demonstrated. But before I test this working hypothesis on the negative connection between peace and Islamismand I will do so by a case study of the Maghribit is pertinent to define peace. Prior to the age of nationalism and the formation of the State of Israel, Muslims and Jews lived in a kind of social peace with one another. This has sometimes been called the Jewish-Islamic symbiosis, and it is invariably celebrated in interreligious dialogues. But is this symbiosis the model we need for a lasting peace in the Middle East? The answer is yes and no. The following anecdote clarifies the limits of the historical legacy. In May 1994, I had the privilege to be a partner in the establishment of a Jewish-Islamic dialogue.1 At the outset, one of the participants, a rabbi, stood up and expressed the gratitude of Jews to Muslims for their past tolerance and protection, but hastened to add this: However, the historical situation has changed. Jews now claim sovereignty and no longer accept the status of dhimmi (protected minority). Acceptance of this fact is a precondition of our dialogue. The inescapable truth is that since the creation of Israeland despite all the injustice its creation involvedJewish-Arab peace is related to acceptance of the right of Jews to sovereignty.2 Existing and past injustice must be dealt with in the framework of democratic peace between sovereign entities. Only after the Peace of Westphaliaafter the establishment of mutually accepted, secular sovereign statesdid religion-based war ceased in Europe. A Muslim-Jewish variety of Westphalia is a precondition of a democratic peace.3 Islamism constitutes one of its principle impediments.

Islamism, Peace, and the Maghrib

The Nature of Islamism

It is the politicization of Islam that produces the ideology of Islamism. Such politicization, in the form of contemporary Islamic fundamentalism, is unprecedented in the history of Islam. Here one cannot but stress the distinction between the religion of Islam and political Islam. Islamismthe Islamic variety of religious fundamentalismis first of all a concept of political order. Religious fanaticism, extremism, and terrorism are only side effects of this phenomenon; they do not pertain to its substance. The underpinning of Islamism is a concept of political order (nizam siyasi) labeled by the Islamists themselves as Gods rule (hakimiyyat Allah).4 Islamism matters in the first place as a vision of an alternative political order, in which Islamists are cast as a counter-lite opposed to the ruling lites. Islam is a religion of divine precepts. In contrast, Islamism is a political concept of order. This Islamism was introduced to the Maghrib from outside the subregion. Ideologically, the major impact came from the Arab East, principally Egypt and Syria, via the medium of the Muslim Brotherhood and the writings of the Egyptian thinker Sayyid Qutb. Politically, the Iranian Revolution had an immense influence on the Maghribthis, despite the apparent difference between Irans Shiite identity and the Sunni identity of Maghribi Muslims. True, the export of the revolution failed, but its ripple effects were noticeable. There is also evidence that many Maghribi Islamists went to Iran, and that several of their movements received funds from Teheran. Militarily, the war in Afghanistan facilitated the shift of political Islam toward violence, particularly in the Arab world. The Mujahidin who fought the infidel Soviets in Afghanistan after the invasion of December 1979 included about 20,000 Arabs (among them, of course, the now-notorious Usamah bin Ladin). Among these warriors of political Islam, there were 2,000 Algerians and an unknown number of Tunisians and Moroccans. At the end of the war, these Islamists returned home to engage in politically destabilizing, irregular military action which often took the form of terrorism. Here it is imperative to reiterate that Islam, as a world religion and belief, is in no way whatsoever a threat. Talk about an Is-

Bassam Tibi

lamic threat is ideological, and needs to be interpreted through the cultural and psychological analysis of stereotypes and the othering of alien cultures. The tendency in some circles to collapse all distinction between Islam and Islamism deserves separate study, and I leave it to another lecturer. Yet in making that crucial distinction, I would emphasize that while Islam is not (and cannot be) a threat to anyone, Islamism certainly isfirst of all, to regional stability in North Africa and other parts of the world of Islam, and also to Arab-Israeli peace. In the Maghrib, the call for an Islamic state unfolded on several levels, most dramatically in Algeria where Islamists resorted to the use of force. At the outset, it was the mosque which constituted the first framework for a gestation of the Islamist discourse (Franois Burgat); in the second stage, the Islamist movement left the obscurity of the mosque... and began via the university to come into public view.5 From the mosque and the academic campus, the Islamist movement entered the urban street and the subproletarian suburb. In each setting, the Islamist movement became the vehicle of counter-lites, determined to displace elites by shattering the system itself. Looking across the Maghrib, the Tunisian movement has the oldest roots. Rashid al-Ghannushi, who led the development of the Tunisian movement from its origins, seems to me the most able Islamist in North Africa.6 He first came in touch with the Muslim Brotherhood during a study stint in Damascus, and the external sources of his thought are easy to identify. Ghannushi is certainly a moderate, but he is clearly not a liberal Muslim. In the early years, the movement under his guidance pronounced itself a political party and professed its acceptance of political pluralism. But other pronouncements suggested that Ghannushi had endorsed such pluralism as a tactic, and continued to regard Islamist incorporation into a multi-party system as a state of transition, leading to the ultimate goal of an Islamic state. In contrast to Tunisia, political Islam came to Algeria first through the states own politics of Arabization, effected in part by importing Muslim Brethren from Egypt. Most prominent among the imported imams was Shaykh Muhammad al-Ghazzali, who was brought to direct the scientific council of the Abd al-Qadir University and then ascended to still higher educational positions. Ghazzali returned

4

Islamism, Peace, and the Maghrib

to Egypt, where he left a similar legacy (including a fatwa that justified the slaying of the Egyptian writer Faraj Fuda).7 The next push was violent, and followed the gradual return home of the Algerian Afghan Arabs. These returnees imparted their military skills to several thousand more members of the Algerian Islamic Salvation Front (FIS).8 Algeria provides the only instance in the Maghrib where an Islamist movement succeeded in mobilizing the suburbs and becoming an obvious threat to stability. If Tunisias Islamist movement is the Maghribs oldest, and Algerias movement is its most powerful, Moroccos movement might best be described as its weakest. Shaykh Abd al-Salam Yasin is little more than a symbol of Moroccan Islamism. In fact, the Islamic legitimacy of the Moroccan kings as commanders of the faithful leaves little Islamic ground for a political opposition. (It goes without saying here that the late King Hassan II championed peace, and his son Muhammad VI is continuing this tradition.) Given the great sectarianism in groups and subgroups among the Islamists of the Maghrib, and the related splits in their movements, their prospects for seizing power are clearly limited. But Islamists, even if they fail to establish the divine-political order they envisage, are nevertheless capable of destabilizing the existing order. The result could be the creation of a chronic disorder, characterized by riots, ethno-religious cleavages and internal wars. Algeria provides a case in point. In this light, Islamism must still be regarded as the major force of opposition in the Maghrib, and a political reality to be reckoned with.

Lasting Peace?

It must also be reckoned with in the equation of regional peace. In my view, Islamic fundamentalism in North Africa is an obstacle to peace in the Mediterranean. The Algerian Islamist Abbasi Madani characterized the role of the mosque in this way: The mission of the mosque is not the same as that of a church.... The mosque is a place in which all the affairs of the umma are treated.... It is from there that the armies left to confront the enemy.9 In historical terms, Abbasi Madani is right. But this is not the religion of Islam as revealed ethics; this is Islam reduced to Islamic history. The historian

5

Bassam Tibi

of early Islamic jihad, Khalid Yahya Blankinship, informs us that the mosque indeed served as a part of the logistics of the Islamic wars of conquest (futuhat).10 But the revival to this concept does disservice to peace in the Mediterranean. Such an interpretation is relevant solely to the historical context of jihad and crusadesthat is, of enmity.11 In our age, in which we need Mediterranean peace and intercultural bridging, we cannot afford to revive that tradition. To the contrary: it is incumbent on us to engage in the politics of preventing the clash of civilizations.12 This must be extended to the Arab-Israeli conflict. The Maghrib is a subregion of the Middle Eastern regional subsystem, and is inevitably involved in the Arab-Israeli conflict and in the search for a peaceful resolution. And the fact is that the Islamists, including those of the Maghrib, would never accept a peace with Israel based on mutual acceptance of sovereignty. A tactical peace cannot be a lasting peace, just as an Islamist state can never be a democratic state, based on democratic pluralism and secular civil society. True, the temporary peace admitted by some Islamists is better than sporadic war. But nothing can ever absolve us from the pursuit of a lasting peace.

NOTES

1. See the coverage by Bassam Tibi, Krieg der Zivilisatione (new enlarged ed.; Munich, 1998), pp. 291ff. 2. Avi Primor and Bassam Tibi, 50 Jahre Israel (Ostry, Trier 1999). 3. See Bassam Tibi, Frieden im Nahen Osten im Lichte einer Vergegenwrtigung des Westflischen Friedens, Osnabrcker Jahrbuch Frieden und Wissenschaft, vol. 6 (1999), pp. 175-86. 4. See Muhammad Salim al-Awwa, Fi al-nizam al-siyasi lil-dawla al-Islamiyya (Cairo, 1983). The term hakimiyyat Allah was first coined by Sayyid Qutb. 5. Franois Burgat, The Islamic Movement in North Africa (Austin, 1993), p. 86f. 6. In 1994, I had the opportunity to spend a week with him on the occasion of an Euro-Mediterranean Dialogue held by Danish Pen in Copenhagen. See both our contributions to Bridging the Cultural Gap, ed. Niels Barfoed (Copenhagen, 1995). 7. For details and references see Bassam Tibi, Im Schatten Allahs. Der Islam und die Menschenrechte (Munich, 1994), pp. 175-78.

Islamism, Peace, and the Maghrib

8. Mark Huband, Warriors of the Prophet. The Struggle for Islam (Boulder, 1999), p. 59. 9. Quoted by Burgat, The Islamic Movement, p. 90. 10. Khalid Y. Blankinship, The End of the Jihad State: The Reign of Hisham Ibn Abd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads (Albany, 1994), p. 15f. 11. See Bassam Tibi, Kreuzzug und Djihad. Der Islam und die christliche Welt (Munich, 1999). 12. Roman Herzog, Preventing the Clash of Civilizations, ed. H. Schmiegelow (London, 1999). Copyright 2001 by Bassam Tibi

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Al Attas Philosophy of Science by AdiasetiaDocumento50 pagineAl Attas Philosophy of Science by AdiasetiaFaris ShahinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Kebangkitan Demokrsi IslamDocumento15 pagineKebangkitan Demokrsi IslamahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Figures Include Direct Business Transaction (DBT)Documento1 paginaFigures Include Direct Business Transaction (DBT)ahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- Professor Tariq Ramadan Is Back To USADocumento7 pagineProfessor Tariq Ramadan Is Back To USAahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Playing With IslamDocumento3 paginePlaying With IslamahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Concept of ShuraDocumento1 paginaConcept of ShuraahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Islamic: Rise and Fall ofDocumento1 paginaIslamic: Rise and Fall ofahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Islam and HomosexualityDocumento3 pagineIslam and HomosexualityahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Open Democracy - December 2012: Extrait Du Tariq RamadanDocumento5 pagineOpen Democracy - December 2012: Extrait Du Tariq RamadanahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Muslims Must Have Faith in AmericaDocumento3 pagineMuslims Must Have Faith in AmericaahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Islam and HomosexualityDocumento3 pagineIslam and HomosexualityahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- No To Forced Marriages Our Duty Our ConscienceDocumento3 pagineNo To Forced Marriages Our Duty Our ConscienceahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Islam & The WestDocumento7 pagineIslam & The WestahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Is It The End of Islamism or The Birth of New Liberal Capitalist IslamistsDocumento3 pagineIs It The End of Islamism or The Birth of New Liberal Capitalist IslamistsahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- Contemporary Islamic Conscience in CrisisDocumento3 pagineContemporary Islamic Conscience in CrisisahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Dead Without Trial AgainDocumento3 pagineDead Without Trial AgainahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- Interview: Extrait Du Tariq RamadanDocumento12 pagineInterview: Extrait Du Tariq RamadanahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- But Can You Be A Gay MuslimDocumento14 pagineBut Can You Be A Gay MuslimahmadsiraziNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Main Stages in English RenaissanceDocumento2 pagineMain Stages in English RenaissanceGuadalupe Escobar GómezNessuna valutazione finora

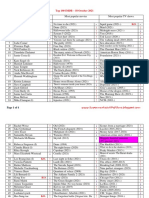

- Top 100 IMDB - 18 October 2021Documento4 pagineTop 100 IMDB - 18 October 2021SupermarketulDeFilmeNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Transpo Case ReportDocumento10 pagineTranspo Case ReportJesse AlindoganNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Issues in The PhilippinesDocumento19 pagineSocial Issues in The PhilippinessihmdeanNessuna valutazione finora

- Code of Ethics For Company SecretariesDocumento2 pagineCode of Ethics For Company SecretariesNoorazian NoordinNessuna valutazione finora

- Ballymun, Is The Place To Live inDocumento10 pagineBallymun, Is The Place To Live inRita CahillNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Anthony Kaferle, Joe Brandstetter, John Kristoff and Mike Kristoff v. Stephen Fredrick, John Kosor and C. & F. Coal Company. C. & F. Coal Company, 360 F.2d 536, 3rd Cir. (1966)Documento5 pagineAnthony Kaferle, Joe Brandstetter, John Kristoff and Mike Kristoff v. Stephen Fredrick, John Kosor and C. & F. Coal Company. C. & F. Coal Company, 360 F.2d 536, 3rd Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Vicente Vs EccDocumento1 paginaVicente Vs EccMaria Theresa AlarconNessuna valutazione finora

- A Couple of Minutes LaterDocumento10 pagineA Couple of Minutes LaterNavi Rai33% (3)

- 1st Group For Cyber Law CourseDocumento18 pagine1st Group For Cyber Law Courselin linNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Admin Tribumal and Frank CommitteeDocumento8 pagineAdmin Tribumal and Frank Committeemanoj v amirtharajNessuna valutazione finora

- Character Evidence NotesDocumento9 pagineCharacter Evidence NotesArnoldNessuna valutazione finora

- 9B Working UndercoverDocumento4 pagine9B Working UndercoverJorge Khouri JAKNessuna valutazione finora

- People of The Philippines, Appellee, vs. MARIO ALZONA, AppellantDocumento1 paginaPeople of The Philippines, Appellee, vs. MARIO ALZONA, AppellantKornessa ParasNessuna valutazione finora

- Partnership PRE-MID PersonalDocumento12 paginePartnership PRE-MID PersonalAbigail LicayanNessuna valutazione finora

- Datatreasury Corporation v. Wells Fargo & Company Et Al - Document No. 581Documento6 pagineDatatreasury Corporation v. Wells Fargo & Company Et Al - Document No. 581Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora

- CharltonDocumento6 pagineCharltonStephen SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- The Complete Book of Magic and WitchcraftDocumento164 pagineThe Complete Book of Magic and WitchcraftTomerKoznichki89% (65)

- Haig's Enemy Crown Prince Rupprecht and Germany's War On The Western FrontDocumento400 pagineHaig's Enemy Crown Prince Rupprecht and Germany's War On The Western FrontZoltán VassNessuna valutazione finora

- Belgian Overseas Vs Philippine First InsuranceDocumento6 pagineBelgian Overseas Vs Philippine First InsuranceMark Adrian ArellanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Chapter 5Documento7 pagineChapter 5Adrian SalazarNessuna valutazione finora

- BasicBuddhism Vasala SuttaDocumento4 pagineBasicBuddhism Vasala Suttanuwan01Nessuna valutazione finora

- ChapterDocumento12 pagineChapterRegine Navarro RicafrenteNessuna valutazione finora

- 6days 5nights Phnom PenhDocumento3 pagine6days 5nights Phnom PenhTamil ArasuNessuna valutazione finora

- COMMISSION ON AUDIT CIRCULAR NO. 81-155 February 23, 1981Documento7 pagineCOMMISSION ON AUDIT CIRCULAR NO. 81-155 February 23, 1981debate ddNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pre-Hispanic Barangay GovernmentDocumento5 pagineThe Pre-Hispanic Barangay GovernmentNestor CabacunganNessuna valutazione finora

- The Locked RoomDocumento3 pagineThe Locked RoomNilolani JoséyguidoNessuna valutazione finora

- William Cooper - Operation MajorityDocumento6 pagineWilliam Cooper - Operation Majorityvaneblood1100% (4)

- Scope of Application of Section 43 of The Transfer of Property Act, 1882.Documento8 pagineScope of Application of Section 43 of The Transfer of Property Act, 1882.অদ্ভুত তিনNessuna valutazione finora

- Verb With MeaningDocumento2 pagineVerb With MeaningJatinNessuna valutazione finora

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaDa EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (23)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentDa EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (7)