Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

7060.2005.12206 (Volume 12 Issue 2 Article First Published Online 8 MAR 2006)

Caricato da

for_booksCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

7060.2005.12206 (Volume 12 Issue 2 Article First Published Online 8 MAR 2006)

Caricato da

for_booksCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Effect of Vacation on Health: Moderating Factors of Vacation Outcome

Gerhard Strauss-Blasche, Barbara Reithofer,Wolfgang Schobersberger, Cem Ekmekcioglu, and Wolfgang Marktl

Background: Vacation has recently become a topic of interest in health research as both beneficial and adverse health effects have been documented. The present study was aimed at identifying vacation characteristics predicting healthrelated vacation outcome. Methods: One hundred ninety-one predominantly white-collar employees (109 female, 82 males; mean age 37.8 yr, range 1662 yr) received a questionnaire in the week after vacation assessing subject characteristics, physical vacation characteristics, the individual structuring of the day, health and social behavior, and stress during vacation as well as the perceived change of recuperation and exhaustion from before to after a vacation. Regression analysis was used to identify variables predicting vacation outcome. Results: Twenty-seven percent of the variance of the change of recuperation and 15% of the change of exhaustion could be explained. Recuperation was facilitated by free time for ones self, warmer (and sunnier) vacation locations, exercise during vacation, good sleep, and making new acquaintances, especially among vacationers reporting higher levels of prevacation work strain. Exhaustion was increased by vacation-related health problems and a greater time-zone difference to home, and was reduced by warmer vacation locations. Conclusion: Health-related vacation outcome is significantly affected by the way an individual organizes his or her vacation.

Vacation, defined by Lounsbury and Hoops as a temporary respite from work lasting several days to several weeks, has presently become a topic of interest in health research.1 A recent study suggests that the frequency of annual vacations for men at risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) is associated with a reduced risk of mortality, which is predominantly attributed to the CHD.2 Also, leisure vacation has been reported to be negatively associated with depression,3 a potential risk factor for CHD,4 in a sample of Japanese male white-collar workers. In longitudinal research with healthy employees, we and others found vacation to be associated with at least short-term improvements of health-related variables such as burnout, mood, and physical complaints.5,6 To date, the mechanisms leading to these results, except for a

Gerhard Strauss-Blasche, PhD, Cem Ekmekcioglu, MD, and Wolfgang Marktl, MD: Department of Physiology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, and Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Biological Rhythm Research, Bad Tatzmannsdorf, Austria; Barbara Reithofer, MA: Department of Physiology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria; Wolfgang Schobersberger MD: Institute for Leisure, Travel and Alpine Medicine, University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology Tyrol, Innsbruck, Austria. Reprint requests: Gerhard Strauss-Blasche, PhD, Department of Physiology, Medical University of Vienna, Schwarzspanierstrasse 17, 1090 Vienna, Austria. J Travel Med 2005; 12:94101.

removal of work stress and an increase of personally available time,5,6 are as yet unclear. On the other hand, vacation may also be associated with adverse health effects for some individuals, potentially leading to leisure sickness or cardiac incidence.7,8 Therefore, the aim of the present study was to identify variables relevant to the individuals vacation that affect both positive and negative health-related vacation outcome.The study is exploratory as little information on the effects of specific vacation attributes on healthrelated vacation outcomes is provided in literature. Our approach was to study physiologic and psychological factors that have a known potential effect on well-being and health in addition to vacation-specific variables potentially moderating vacation outcome. Four aspects of vacation were studied: (1) physical aspects of vacation, including vacation duration assuming vacation benefits to increase with longer vacation,9 the average temperature at the vacation site as a climatic variable,10 the timezone difference to account for jet lag,11 and the travel time to account for travel stress12; (2) the organization of daily routine, including the number of provided meals and the planning of the day, both potential exogenous pacemakers affecting health,13 self-determination of daily actions, and time for ones self and needs as leisure factors contributing to psychological well-being 14,15 ; (3) health and social behavior including the amount of physical activity,16 the duration and quality of sleep,17 and making new acquaintances as known factors improving health and mood18; and (4) potential stressors during

94

S t r a u s s - B l a s ch e e t a l , M o d e r a t i n g F a c t o r s o f Va c a t i o n

95

vacation including health problems and interpersonal conflicts.19,20 Methods

Subjects and Procedure

Subjects were employees of a large travel agency and their relatives.A questionnaire, including a cover letter asking for participation in a study of the effect of vacation type and vacation activities on recuperation and well-being, was e-mailed or handed to approximately 500 recipients. Subjects were asked to fill out the questionnaire within the 2 weeks following their vacation. Of the 295 returned questionnaires (response rate 59%), only the 239 filled out by occupationally active individuals were included in the study. Of these, 38 had to be rejected owing to incomplete answers or delayed responses, and 10 were rejected owing to a vacation duration > 4 weeks.The latter criterion was established as vacations > 4 weeks are unusual and the frequency of these vacations was small in the current sample. Of 191 remaining study participants, 109 were females and 82 were males with a mean age of 37.8 years (SD = 11.3; range 1662 yr). Most study participants had partners (72.8%); 24% had children younger than 14 years.The study reflected a variety of locations, most commonly in Austria (27%), followed by Italy (17%), Greece (13%), northern Europe (11%), and Croatia (8%).About 5% of the subjects traveled to other continents.Approximately 80% of the subjects filled out their questionnaire within the first week of return; 30% completed it during the first 3 days after vacation.

Measures

.91. Scale 2 (exhaustion) was composed of three items (In comparison to the 2 weeks before vacation, I now feel more indifferent and apathetic, more depressed, and more exhausted) with a scale reliability of Cronbachs = .73.To describe subject characteristics, age, sex, and an estimate of physical as well as mental strain of daily work were assessed, the latter two because we assumed that more strained individuals would show a greater improvement during vacation.23 The independent variables described four different aspects of vacation: (1) physical vacation characteristics (duration, average temperature, time-zone difference, time to reach destination), (2) organization of the day (number of provided meals, self-determination of ones daily actions, planning of day ahead, time for ones self and needs), (3) health and social behavior (physical activity during vacation, average sleep duration during vacation, sleep quality, making new acquaintances), and (4) stress during vacation (health problems, interpersonal conflicts).A complete list of items and their response frequencies is presented in Table 1.

Statistics

The intercorrelation between the subject characteristics and the independent variables as well as their correlation with the two outcome measures was calculated. The predictive effect of these variables on the two outcome measures was analyzed using two separate linear regression analyses. Vacationer characteristics and the four groups of items representing the different aspects of vacation were entered in five separate blocks.Total R2, R2 change for each block, and values for every variable were listed.None of the variables had a variance inflation factor of greater than 1.5.24 Results The variables of subject and vacation description and their frequency distribution are illustrated in Table 1.The intercorrelation of these variables is illustrated in Table 2. To predict vacation outcome, we conducted two regression analyses for both outcome measuresrecuperation and exhaustion (Table 3). Five groups of variables were entered consecutively as separate blocks.The first block encompassed variables describing the vacationers, the second block variables described physical vacation characteristics, the third block described the way vacationers organized their day, the fourth block related to health and social behavior, and the fifth block related to stressful events during vacation. Twenty-seven percent of the change of recuperation could be explained by the descriptive variables. The vacationer characteristics (block 1) explained 7% of the variance, with the mental strain of prevacation daily

Selected items of a standardized German quality-oflife questionnaire were used as outcome measure.21 This quality-of-life measure, although initially constructed for hypertensive patients, encompasses a broad variety of items related to positive and negative well-being and selfperceived fitness and is quite sensitive to change. From these three scales, 11 items were chosen, and subjects were asked to rate their current state of well-being in comparison to the state 2 weeks before their vacation.This approach is a modification of the postintervention then rating devised to minimize errors in the measurement of change.22 Two scales were derived from the 11 items by factor analysis, together explaining 60.3% of the variance. One item was discarded owing to a low factor loading.Scale 1 (recuperation) was composed of seven items (In comparison to the 2 weeks before vacation, I now feel mentally fitter, feel more balanced and relaxed, can concentrate better during work, feel physically fitter, do my work more easily, am in a better mood, and feel more recuperated) with a scale reliability of Cronbachs =

96

J o u r n a l o f Tr a v e l M e d i c i n e , Vo l u m e 1 2 , N u m b e r 2

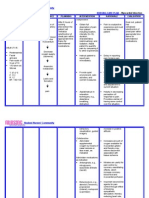

Table 1 Subject Characteristics, Variables Describing Vacation, and Outcome Measures Characteristic/Variable Age (yr) Range 1624 2530 3039 4049 5062 Low 2 3 4 High Low 2 3 4 High 37 814 1521 2228 0 12 58 1520 2125 2630 3045 13 47 812 1348 None 1 (breakfast) 2 3 Not at all 2 3 4 Very much so Not at all 2 3 4 Very much so None 2 3 4 Adequate None 2 3 4 Very often 57 8 9 1011 Bad Response Frequency (%) 12 15.7 28.3 26.2 17.8 37.6 40.7 11.2 7.8 2.7 3.5 17.4 5.4 33.3 40.3 34.9 43.8 12.8 8.5 64.3 33 2.7 14.3 27.9 40 17.8 36.4 37.6 16.3 9.7 34 27.2 22.5 16.2 2.1 11.0 2.1 16.1 68.6 25.7 40.3 9.4 20.4 4.2 2.6 16.2 2.6 31.9 46.6 20.4 26.2 24.1 22.0 7.3 8.9 24.1 39.3 27.7 1.6 Continued

Physical strain of daily work (scale*)

Mental strain of daily work (scale*)

Duration of vacation (d)

Time zone difference to home (h) Average temperature at vacation site (C)

Time to travel to vacation site (h)

Provided meals (number)

Self-determination of daily actions (scale*)

Planning the day ahead (scale*)

Time for ones self and needs (scale*)

Physical activity during vacation (scale*)

Average duration of sleep (h)

Sleep quality (scale*)

S t r a u s s - B l a s ch e e t a l , M o d e r a t i n g F a c t o r s o f Va c a t i o n

97

Table 1 (Continued) Characteristic/Variable Range 2 3 4 Good Not at all 2 3 4 Very much so None 2 3 4 Very often Not at all 2 3 4 Very much so 019 2039 4059 6079 80100 019 2039 4059 6079 80100 Response Frequency (%) 15.7 3.7 25.1 53.9 27.2 32.5 6.3 19.4 14.7 78.0 13.6 5.2 3.1 0 69.6 20.9 3.7 3.1 2.6 5.2 12.6 24.6 41.9 15.7 71.2 17.3 9.4 2.1 0

Making new acquaintances (scale*)

Health problems during vacation (scale*)

Interpersonal conflicts (scale*)

Recuperation (scale 0100)

Exhaustion (scale 0100)

*Five-point Likert scale.

work positively predicting outcome; that is, individuals with high job strain experienced greater recuperation during vacation. Age, sex, and physical strain were not significantly associated with recuperation. Physical vacation characteristics (block 2) explained 6% of the variance, with warm temperature at the vacation site predicting recuperation. Despite a single-order correlation, the duration of vacation did not predict recuperation in the regression analysis nor did time-zone difference or travel time. The way vacationers organized their day (block 3) explained 8% of the variance.Whereas the number of provided meals,the extent of self-determination of ones daily activities, and the extent vacationers tended to plan their day ahead did not predict recuperation, the amount of time vacationers perceived to have for themselves and their needs was positively and strongly associated with recuperation. Health and social behaviors (block 4) explained 7% of the perceived change of recuperation.Vacationers engaging in more physical activity, having a better quality of sleep, and making new acquaintances perceived greater recuperation after vacation. Sleep duration during vacation did not significantly predict recuperation. Potential vacation stressors (block 5) predicted 2% of the

variance. Interpersonal conflicts were negatively related; health problems were unrelated to recuperation. Overall, 15% of the second outcome measure, the perceived change of exhaustion, could be explained by the descriptive variables.The vacationer characteristics (block 1) did not predict exhaustion. Physical vacation characteristics (block 2) predicted 7% of the change of exhaustion,with a greater time-zone difference being positively related to exhaustion and the average temperature at the vacation site negatively related to exhaustion. The duration of vacation and the time to travel to the vacation destination were unrelated. The individual organization of daily vacation activities (block 3) did not predict exhaustion. Also, health and social behaviors (block 4) were unrelated to exhaustion.Stress during vacation (block 5) explained 3% of the variance, with health problems, but not interpersonal conflicts, predicting exhaustion. Discussion Even though studies in tourism and leisure research have assessed the effect of vacation-related factors on vacation satisfaction,25 the present study is, to our knowl-

98

J o u r n a l o f Tr a v e l M e d i c i n e , Vo l u m e 1 2 , N u m b e r 2

Table 2 Intercorrelation of Subject and Vacation Characteristics* Characteristic 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Age Sex (1= m, 2 = f) Physical strain of daily work Mental strain of daily work Duration of vacation (d) Time-zone difference to home (h) Average temperature at vacation site Time to travel to vacation site (h) Number of provided meals Self-determining ones daily actions Planning the day ahead Time for ones self and needs Physical activity duringvacation Average duration of sleep (h) Sleep quality Make new acquaintances Health problems during vacation Interpersonal conflicts 1 2 3 4 5 .24 .24 .26 .29 .19 .26 .22 .27 .32 .30 .16 .17 .14 .21 .18 .27 .27 .22 .32 .30 .37 .19 .15 .17 .19 .18 .18 .22 .25 .17 .21 .22 .37 .17 .21 .18 .27 .18 .18 .14 .21 .25 .17 .19 .15 6 7 8 9 10 .16 11 .17 12 13 14 15 16 .19 17 .21 .21 .29 .19

*Only significant correlations (p < .05) are listed.

edge, the first one investigating the effect of vacation descriptors on health-related vacation outcome. Relevant vacationer characteristics were thereby considered simultaneously.Health-related vacation outcome was measured using two variables derived by factor analysis of rephrased items from a standardized German quality-of-life questionnaire21: recuperation, reflecting positive mood, wellbeing and perceived mental and physical fitness; and exhaustion, reflecting depressive mood and fatigue.The distinction between these two measures can be seen as similar to the established distinction between positive and negative well-being.26 Overall, a qualified proportion of the perceived change of recuperation during vacation could be predicted, indicating that the vacation descriptors did actually tap relevant aspects of vacation. In contrast, only a relatively small amount of the change of exhaustion could be explained, presumably owing to the small increase of exhaustion reported. Of the variables describing the vacationers, sex did not affect vacation outcome in this study, although a

greater improvement of burnout in females has been reported elsewhere.5 Age was associated with a number of differences in vacation organization, such as vacation duration and travel time, but did not affect outcome on its own. Higher mental prevacation work strain was associated with greater vacation-related recuperation, a result that is in accordance with the removal of work strain hypothesis of vacation,27 and has been found for biologic and nonbiologic markers.8,23 Individuals experiencing high levels of work strain show greater improvements of well-being when relieved from this strain (eg,during vacation) than do those who do not experience high work strain. A similar result was not found for physical work strain, presumably because of its small prevalence in the predominantly white-collar-employee study sample. Of the physical vacation characteristics, vacation duration did not predict vacation outcome despite a positive single-order correlation. This is a surprising result, as one would assume that a longer vacation would be more recuperating. It has been found that quality of sleep increases throughout vacation, but mood essentially

S t r a u s s - B l a s ch e e t a l , M o d e r a t i n g F a c t o r s o f Va c a t i o n

99

Table 3. Regression Analysis Predicting Vacation Outcome Block Characteristics/Variables Values Recuperated Exhausted .15* Single-Order Correlations Recuperated Exhausted

.30*** Total R2 1. Subject characteristics (R2 change recuperation: .08**; R2 change exhaustion: .00) Age .12 Sex .10 Physical strain of daily work .12 Mental strain of daily work .17** 2. Physical vacation characteristics (R2 change recuperation: .06*; R2 change exhaustion: .07**) Duration of vacation (d) .09 Average temperature at vacation site .20** Time-zone difference to home (h) .16* Time to travel to vacation destination (h) .01 3. Individual organization of day (R2 change recuperation: .08**; R2 change exhaustion: .03) Number of provided meals .08 Self-determination of ones daily activities .08 Planning the day ahead .09 Time for ones self and needs .21** 4. Health and social behavior (R2 change recuperation: .07**; R2 change exhaustion: .01) Physical activity during vacation .14* Average sleep duration during vacation (h) .08 Sleep quality .14* Making new acquaintances .16* 5. Stress during vacation (R2 change recuperation: .02; R2 change exhaustion: .03*) Health problems during vacation .07 Interpersonal conflicts .11

.09 .05 .00 .02

.11 .04 .09 .20**

.03 .05 .00 .02

.06 .22** .20** .06

.18* .16* .01 .07

.03 .13 .17* .09

.00 .13 .07 .05

.08 .03 .17* .29***

.05 .18* .03 .13

.08 .01 .04 .02

.17* .16* .24* .12

.08 .03 .05 .09

.17* .08

.06 .11

.17* .08

Variables were entered in five blocks; R2 change of each block (the amount of variance explained by those variables) both for recuperation and exhaustion as well as values and single-order correlations are displayed (*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001).

finds its peak after 7 days.9,28 As both variables show the greatest improvement in the first 3 days, several-day vacations may also have a relevant impact on well-being and health, although vacation-related factors such as travel strain and altitude have to be taken into account.28 Another surprising result is the strong positive effect of the average temperature at the vacation site on both outcome measures. As most vacations in warmer climates took place in the summer in the Mediterranean area, the effect presumably is primarily due to sun exposure, a variable known to affect mood positively.10,29 In addition, lifestyle factors also may contribute to this result, illustrated by the association of average temperature with some variables of vacation organization. An expected result is that a greater time-zone difference was related to greater exhaustion, pointing to the well-known phenomenon of jet lag,11 even though the number of time zones crossed was moderate.On the other

hand, the travel time, which ranged from 1 to 48 hours, did not affect vacation outcome.Although related to the strain of travel (r = .31), the type of transportation may be more relevant than the duration, as has been found in a recent study investigating vacation-related factors on myocardial infarction.7 The individual organization of the day, for example, how vacationers planned their time, was the strongest predictor of recuperation among the four studied aspects of vacation.This was owing to the large positive impact of having enough free available time for ones self and ones needs, which is in accordance with the notion that relaxation and freedom of obligations are important aspects of leisure leading to well-being.15,30 The result replicates a previous result obtained by our group,6 and it can be seen as related to the finding that low-effort, that is, relaxing, undemanding activities, enhance afterwork recovery.31 A greater self-determination of ones

100

J o u r n a l o f Tr a v e l M e d i c i n e , Vo l u m e 1 2 , N u m b e r 2

daily activities, however, was not related to recuperation, as has been suggested in leisure research.14 Possibly, selfdetermination or self-control is only important in the presence of stress, as underlined by Karaseks demandcontrol model and illustrated in the negative singleorder correlation with postvacation exhaustion in the present study.32 Also contrary to our expectations,the variables associated with how individuals structured their day (number of provided meals, planning of day ahead) did not affect vacation outcome. Based on our knowledge of residential spa therapy and on the presumed positive effect of exogenous pacemakers,13,33 we had imagined that a moderate amount of daily structure would positively affect well-being and health, but this hypothesis was not supported. Health and social behaviors also predicted recuperation strongly. The amount of physical activity, the quality of sleep, and the extent of making new acquaintances were all positively associated with recuperation. Physical activity is a known factor improving well-being and health.16 In a recent study we found a vacation incorporating regular walking tours to improve perceived health in individuals with metabolic syndrome.28 Quality of sleep not only affects well-being but is also affected by well-being.17 Therefore, the positive effect of good sleep should be interpreted cautiously as good sleep may also be a result of greater recuperation. Sleep quantity, on the other hand, did not predict vacation outcome, a result also in line with other research finding sleep duration less relevant for health and mood,34 although a positive single-order correlation was present. Making new acquaintances was associated with greater recuperation, presumably reflecting the well-known moodenhancing effect of social interaction.18 Stress in the form of health problemsbut not in the form of interpersonal conflictsnegatively affected vacation outcome, with health problems leading to increased postvacation exhaustion. Health problems are a known phenomenon during vacation and travel and are attributable to both environmental and psychological factors.8,19 Although interpersonal conflicts are an obvious stressor affecting well-being,their impact on vacation outcome could not be detected in the present study.20 There are some limitations to this study that have to be addressed. Asking the vacationers to estimate the degree of change from 2 weeks before to after vacation, may be subject to two forms of measurement error: (1) individuals may not be rating change but may be rating their current state, and (2) individuals who are appraising change may be subject to reporting or memory error.35 If the first error applied, the results would reflect an association between a general mood state and

a style of vacation organization, rather than an effect of vacation organization on perceived health, thereby reversing the expected direction of causation.This explanation cannot be completely ruled out but seems unlikely owing to the positive association of perceived workload and positive vacation outcome. If individuals were rating their current state, then a negative association should be present, if any, with high workload potentially being associated with poorer mood and health.36,37 A reporting or memory error cannot be ruled out, but as only effects in relation to vacation organization were assessed, a systematic memory or reporting error should not have affected the results. Conclusions The study implies that the effect of vacation cannot merely be explained by the removal of work stress, as has been indicated in previous studies.5,27 Rather, the way an individual organizes his or her vacation makes a difference in regard to health-related vacation outcome. Having enough time for ones self and ones needs, exercising, getting good sleep, and socializing in a warm vacation climate facilitate recuperation, especially in vacationers reporting higher levels of prevacation mental strain. On the other hand, larger time-zone differences to home and health problems affect vacation outcome negatively.As has been stressed by Eden in a recent article,30 further studies are necessary to establish more consistent criteria regarding vacation description and individual vacation organization and their effects on well-being and health. Declaration of Interests The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose. Acknowledgment We would like to express our gratitude to Mrs. Barbara Hadek for proofreading the final version of the manuscript. References

1. Lounsbury JW, Hoops LL.A vacation from work: changes in work and non-work outcomes. J Appl Psychol 1986; 71:392401. 2. Gump BB, Matthews KA. Are vacations good for your health? The 9-year mortality experience after the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Psychosom Med 2000; 62:608612.

S t r a u s s - B l a s ch e e t a l , M o d e r a t i n g F a c t o r s o f Va c a t i o n

101

3. Tarumi K, Hagihara A. An inquiry into the causal relationship among leisure vacation, depression, and absence from work. Sangyo Ika Daigaku Zasshi 1999; 21:289307. 4. Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I. Going to the heart of the matter: do negative emotions cause coronary heart disease? J Psychosom Res 2000; 48:323337. 5. Westman M, Eden D. Effects of a respite from work on burnout: vacation relief and fade-out. J Appl Psychol 1997; 82:516527. 6. Strauss-Blasche G, Ekmekcioglu C, Marktl W. Does vacation enable recuperation? Changes in well-being associated with time away from work. Occup Med (Lond) 2000; 50:167172. 7. Kop WJ,Vingerhoets A, Kruithof GJ, Gottdiener JS. Risk factors for myocardial infarction during vacation travel. Psychosom Med 2003; 65:396401. 8. Vingerhoets AJ,Van Huijgevoort M,Van Heck GL. Leisure sickness: a pilot study on its prevalence, phenomenology, and background. Psychother Psychosom 2002; 71:311317. 9. Roth S, Silberer G. Urlaubsstimung und Tourismusmarketing. [Holiday mood and tourist marketing.] Planung und Analyse 2000; 2000(2):7783. 10. Molin J, Mellerup E, Bolwig T, et al.The influence of climate on development of winter depression. J Affect Disord 1996; 37:151155. 11. Loat CE, Rhodes EC. Jet-lag and human performance. Sports Med 1989; 8:226238. 12. Raggatt PT, Morrissey SA.A field study of stress and fatigue in long-distance bus drivers. Behav Med 1997; 23:122129. 13. Piggins HD.Human clock genes.Ann Med 2002;34:394400. 14. Coleman D,Iso-Ahola SE.Leisure and health:the role of social support and self-determination.J Leisure Res 1993;25:111128. 15. Caldwell LL, Smith EA. Leisure: an overlooked component of health promotion.Can J Public Health 1988;79(2):S44S48. 16. Scully D, Kremer J, Meade MM, et al. Physical exercise and psychological well being: a critical review. Br J Sports Med 1998; 32:111120. 17. Pilcher JJ, Ott ES.The relationships between sleep and measures of health and well-being in college students: a repeated measures approach. Behav Med 1998; 23:170178. 18. Argyle M, Martin M.The psychological causes of happiness. In: Starck F, Argyle M, Schwarz N, eds. Subjective wellbeing. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1991:74100. 19. Rogers HL, Reilly SM. A survey of the health experiences of international business travelers. Part onephysiological aspects.AAOHN J 2002; 50:449459. 20. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Cacioppo JT, Malarkey WB. Marital stress: immunologic, neuroendocrine, and autonomic correlates.Ann N Y Acad Sci 1998; 840:656663. 21. Siegrist J, Broer M, Junge A. Profil der Lebensqualitaet chronisch Kranker (PLC). Goettingen: Beltz, 1996.

22. Howard GS, Ralph KM, Gulanick NA, et al. Internal invalidity in pretest-posttest self-reporting evaluations and a reevaluation of retrospective pretests. Appl Psychol Meas 1979; 3:123. 23. Strauss-Blasche G, Ekmekcioglu C, Marktl W. Serum lipid responses to a respite from occupational and domestic demands in subjects with varying levels of stress. J Psychosom Res 2003; 55:521524. 24. Miles J, Shevlin M.Applying regression and correlation. London: Sage, 2001. 25. Lounsbury JW, Hoops LL.An investigation of factors associated with vacation satisfaction. J Leisure Res 1985; 17(1):113. 26. Chamberlain K. On the structure of subjective well-being. Soc Ind Res 1988; 20:581604. 27. Westman M, Etzion D. The impact of vacation and job stress on burnout and absenteeism. Psychol Health 2001; 16:595606. 28. Strauss-Blasche G, Riedmann B, Schobersberger W, et al.Vacation at moderate and low altitude improves perceived health in individuals with metabolic syndrome. J Travel Med 2004; 11:300306. 29. Magnusson A, Boivin D. Seasonal affective disorder: an overview. Chronobiol Int 2003; 20:189207. 30. Eden D. Job stress and respite relief: overcoming high-tech tethers. Explor Theoret Mech Perspect 2001; 1:143194. 31. Sonnentag S.Work, recovery activities, and individual wellbeing: a diary study. J Occup Health Psychol 2001; 6:196210. 32. de Lange AH,Taris TW, Kompier MA, et al.The very best of the millennium: longitudinal research and the demandcontrol-(support) model. J Occup Health Psychol 2003; 8:282305. 33. Hildebrandt G, Gutenbrunner C. Die KurKurverlauf, Kureffekt und Kurerfolg. [Spa therapyits course, effects and health improvements.] In: Gutenbrunner C, Hildebrandt G, eds. Handbuch der Balneologie and medizinischen Klimatologie. Berlin: Springer, 1998:85186. 34. Pilcher JJ, Ginter DR, Sadowsky B. Sleep quality versus sleep quantity: relationships between sleep and measures of health, well-being and sleepiness in college students. J Psychosom Res 1997; 42:583596. 35. Allison PJ, Locker D, Feine JS. Quality of life: a dynamic construct. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45:221230. 36. Repetti RL. The effects of workload and the social environment at work and health. In: Goldberger L, Breznitz S, eds. Handbook of stress. New York: The Free Press, 1993:368385. 37. Strauss-Blasche G, Ekmekcioglu C, Marktl W. Moderating effects of vacation on reactions to work- and domestic stress. Leisure Sci 2002; 24:113.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- S R T S: OME Esearch Opics For TudentsDocumento3 pagineS R T S: OME Esearch Opics For Tudentsfor_booksNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5795)

- CS 188 Introduction To Artificial Intelligence Fall 2018 Note 1Documento13 pagineCS 188 Introduction To Artificial Intelligence Fall 2018 Note 1for_booksNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Detailed Analysis of The Binary SearchDocumento10 pagineDetailed Analysis of The Binary Searchfor_booksNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Algorithm Correctness and Time ComplexityDocumento36 pagineAlgorithm Correctness and Time Complexityfor_booksNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Holiday Trips On Individuals' Subjective Wellbeing (Doctoral Dissertation) - Available FromDocumento3 pagineHoliday Trips On Individuals' Subjective Wellbeing (Doctoral Dissertation) - Available Fromfor_booksNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- LocationDocumento1 paginaLocationfor_booksNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Computer Architecture - Chapt 5Documento45 pagineComputer Architecture - Chapt 5for_booksNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Lose Weight With Reiki PDFDocumento19 pagineLose Weight With Reiki PDFAfua Oshun100% (3)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Demystifying The Diagnosis and Classification of Lymphoma - Gabriel C. Caponetti, Adam BaggDocumento6 pagineDemystifying The Diagnosis and Classification of Lymphoma - Gabriel C. Caponetti, Adam BaggEddie CaptainNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- 36450378Documento109 pagine36450378Seiba PerezNessuna valutazione finora

- Saraf Perifer: Dr. Gea Pandhita S, M.Kes, SpsDocumento28 pagineSaraf Perifer: Dr. Gea Pandhita S, M.Kes, Spsludoy1Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Imperforate Anus PDFDocumento2 pagineImperforate Anus PDFGlyneth FranciaNessuna valutazione finora

- 08 Chapter 3 Pyrazole AppDocumento100 pagine08 Chapter 3 Pyrazole AppSaima KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- List of New Drugs Approved in The Year 2023decDocumento4 pagineList of New Drugs Approved in The Year 2023decJassu J CNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- MPUshtrimet 20162017 Verore FDocumento98 pagineMPUshtrimet 20162017 Verore FJeronim H'gharNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Case Study Breast CancerDocumento3 pagineCase Study Breast CancerJustin Joshua Derilo OrdoñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Current Issues in Postoperative Pain Management PDFDocumento12 pagineCurrent Issues in Postoperative Pain Management PDFikm fkunissulaNessuna valutazione finora

- Efficacy and Adverse Events of Oral Isotretinoin For Acne: A Systematic ReviewDocumento10 pagineEfficacy and Adverse Events of Oral Isotretinoin For Acne: A Systematic ReviewFerryGoNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Daftar Harga Pengujian Dan Kalibrasi Alat KesehatanDocumento3 pagineDaftar Harga Pengujian Dan Kalibrasi Alat KesehatanVIDYA VIRA PAKSYA PUTRANessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- David Blaine BiographyDocumento7 pagineDavid Blaine BiographyPunkaj YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Care Plan Myocardia InfarctionDocumento3 pagineNursing Care Plan Myocardia Infarctionaldrin1920Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2002 Solution-Focused Brief TherapyDocumento9 pagine2002 Solution-Focused Brief Therapymgnpni100% (1)

- Photocatalysis PDFDocumento8 paginePhotocatalysis PDFLiliana GhiorghitaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Quantitative Analysis of The Lifting Effect Of.10Documento12 pagineQuantitative Analysis of The Lifting Effect Of.10Arcelino FariasNessuna valutazione finora

- FB-08 05 2023+furtherDocumento100 pagineFB-08 05 2023+furtherP Eng Suraj Singh100% (1)

- Anti - Diabetic Activity of Ethanolic Extract o F Tinospora Cordifolia Leaves.Documento4 pagineAnti - Diabetic Activity of Ethanolic Extract o F Tinospora Cordifolia Leaves.Gregory KalonaNessuna valutazione finora

- Intrathecal Morphine Single DoseDocumento25 pagineIntrathecal Morphine Single DoseVerghese GeorgeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Fiji Times Jan 7Documento48 pagineFiji Times Jan 7fijitimescanadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Genetic Disorders Screening and PreventionDocumento36 pagineGenetic Disorders Screening and PreventionManovaPrasannaKumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Tushar FinalDocumento29 pagineTushar FinalRaj Prixit RathoreNessuna valutazione finora

- Gray On EcopsychologyDocumento10 pagineGray On EcopsychologyGiansar26Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vocabulary Revision PhysiotherapyDocumento4 pagineVocabulary Revision PhysiotherapyHuong Giang100% (2)

- 101 Storie ZenDocumento16 pagine101 Storie ZendbrandNessuna valutazione finora

- Consent Form - EmployerDocumento1 paginaConsent Form - EmployerShankarr Kshan100% (1)

- A Case Study On Ascites of Hepatic OriginDocumento4 pagineA Case Study On Ascites of Hepatic OriginFaisal MohommadNessuna valutazione finora

- Dermatome Myotome SclerotomeDocumento4 pagineDermatome Myotome SclerotomeAdhya TiaraNessuna valutazione finora

- 95 Formulation and Evaluation of Diclofenac Sodium Gel by Using Natural PolymerDocumento3 pagine95 Formulation and Evaluation of Diclofenac Sodium Gel by Using Natural PolymerJulian Kayne100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)