Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Jurnal Kegawatdaruratan Medik

Caricato da

Wahyuni Uni RamadhaniTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Jurnal Kegawatdaruratan Medik

Caricato da

Wahyuni Uni RamadhaniCopyright:

Formati disponibili

CLINICAL REPORT

Australian Dental Journal 2002;47:(3):259-261

Chest pain in the dental surgery: A brief review and practical points in diagnosis and management

PJ Chapman*

Abstract If a dental patient develops chest pain it must always be managed promptly and properly, i.e., the practitioner immediately stops the procedure and, being aware of the patients medical history, questions the patient regarding the nature of the pain to help determine the likely diagnosis. It will most likely be a manifestation of coronary artery disease (synonymous with ischaemic heart disease), i.e., angina pectoris or acute myocardial infarction, most usually the former. Angina will usually resolve with proper intervention whereas up to about onehalf of myocardial infarction cases will develop cardiac arrest, mostly in the first few hours, and this will be fatal in up to two-thirds of cases. As health care professionals, dental practitioners have an inherent duty of care to be able to initiate appropriate care if such a medical emergency occurs.

Key words: Chest pain, dental patient. (Accepted for publication 28 November 2001.)

with the patients medical practitioner where indicated, plus provision of adequate local anaesthesia and stress minimization. Cardiac arrest patients should also be identified, e.g., history of moderate or severe hypertension, heart failure, insulin dependant diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, etc.4,5 Medical advice may need to be sought and in some cases this may involve referral to a specialist, i.e., physician or cardiologist.4,5 Accepted practices4-11 The practitioner should refamiliarize himself/herself regarding the medical history and current medication of all cardiac risk patients at the start of an appointment. The practitioner should recall that ischaemic cardiac pain is usually located in the centre of the front of the chest, i.e., retrosternal, is of variable intensity, often described as a feeling of tightness or heaviness of the chest and can radiate to the left shoulder and arm and, less commonly, to the left side of the neck and mandible. Anginal pain tends to be similar for each individual each time it occurs whereas the pain of AMI is generally of greater intensity than that of angina and is often described as crushing in nature. Also the AMI patient may be cyanotic while nausea and vomiting are also common these features are rarely seen in angina. For the patient with a history of angina, administer a prophylactic dose of glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) a few minutes before commencing the appointment. (GTN presentations: tablet dose 0.6mg; spray dose 0.4mg.) It is generally recommended that GTN be kept as an emergency drug and GTN spray is the preferred presentation because of its longer shelf-life. If they experience their typical anginal chest pain later in the appointment, sublingual GTN should be administered in the recommended fashion, i.e., one dose about every five minutes, up to a maximum of three doses until the pain is relieved and administer supplemental oxygen. However, because GTN may cause hypotension with reflex tachycardia, the practitioner, who is monitoring basic signs (consciousness, colour, pulse and blood pressure (BP)), will check the systolic BP before subsequent doses if this is <100mmHg, withhold subsequent doses of GTN as otherwise myocardial

259

INTRODUCTION The occurrence of chest pain in a dental patient is uncommon. A recent estimate from an Australian survey of medical emergencies in the dental office is that a practitioner would experience one case of angina in a career of 40 years whereas the incidence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was about one-in-ten dentists, also in a 40 year career.1 These and other results are recorded in Table 1 and compared to the results of two similar surveys.2,3 Responding immediately to a patient with chest pain is critical to a successful outcome. This will be outlined in the following section. DISCUSSION The basis of safe practice is a complete and up-todate medical history for all patients, plus, especially for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), liaison

*Senior Lecturer (Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery) and Medical Officer, School of Dentistry, The University of Queensland.

Australian Dental Journal 2002;47:3.

Table 1. Occurrence of angina, AMI and cardiac arrest in dental practice1-3

Country No of dentists surveyed Frequency of chest pain cases per dentist per year % of chest pain cases which were angina Frequency of cardiac arrest cases per dentist per year % survival of cardiac arrest cases % of medical emergencies experienced which were cardiac arrests* Australia (1997)1 811 0.03 93 <0.005 75 UK (1999)2 302 0.2 96 <0.005 100 UK (1999)3 1093 0.03 90 <0.005 53

<0.01

0.45

1.0

(*medical emergencies does not include vasovagal syncope or hyperventilation).

oxygen consumption will be increased by the reflex tachycardia and more doses will increase the myocardial ischaemia. The risk of hypotension occurring is minimized if the patient is initially placed in a semi-reclined position (the preferred position for all patients experiencing chest pain). Of course, in the case where reflex hypotension occurs and the pain persists, call 000 immediately. If the pain is relieved by GTN and basic signs are normal, and the patient so desires, it would generally be considered safe to continue the appointment. Otherwise, consider contacting the patients medical practitioner and discuss additional measures to prevent recurrence, e.g., slow release GTN skin patches applied at least four hours before the appointment, oral sedation, etc. However, if in the previous scenario the pain is not considerably eased within 10 minutes from commencing the trial of GTN, or fully relieved within 15 minutes, or recurs, presume an AMI and call 000 immediately; continue administering oxygen and prepare for possible cardiac arrest. If the chest pain experienced by the anginal patient is of a different character than usual, or more severe than ever before, or requires a higher dose of GTN than usual for relief, presume an AMI and contact 000 immediately. If a patient with a history of both AMI and angina develops chest pain in the surgery, always presume it is an AMI and call 000 immediately. If a patient develops chest pain for the first time, always presume it is an AMI. Medical aid should be sought immediately if there is any doubt as to the cause of the patients chest pain. If the practitioner suspects an AMI at the start, then, after calling 000 and awaiting their arrival a dose of GTN can be administered but only after confirming that the systolic BP is above 100mm Hg. Otherwise do not administer. The GTN will only partially or

260

temporarily diminish the pain of an AMI, but will reduce myocardial oxygen consumption as well as increasing myocardial perfusion, thereby improving the prognosis. A second dose can be given (after confirming the BP) about five minutes later. Nitrous oxide, e.g., Entonox can also be used for continuing pain. Additionally, in the same scenario, administer a soluble aspirin tablet (300mg) early because of its antithrombotic effect, i.e., it will limit the area of infarction of course do not administer if there are contraindications, e.g., allergy, bleeding disorder, etc. Oral absorption occurs rapidly (as first-pass metabolism is by-passed) and the patient is told to hold the tablet under the tongue, or in the buccal sulcus, and to avoid swallowing it. If this is not practical at the time, e.g., the patient is nauseous, the patient is given a dissolved soluble aspirin tablet which will be effective within 20-30 minutes. Do not perform elective treatment within the first six months on a patient who has suffered an AMI. Any emergency work in this time must be done as a medically monitored case, because the risk of reinfarction is greatly increased in this period with a corresponding increased mortality rate. The medically monitored case is usually done with intravenous sedation and local anaesthesia with an anaesthetist in attendance in a hospital facility the patient is kept on supplemental oxygen via nasal prongs under continuous electrocardiogram and pulse oximetry monitoring with provision for advanced cardiac life support including a defibrillator. After six months, general dental treatment can be performed if there has been an uncomplicated recovery, but with close monitoring. However, the patients medical practitioner must always be contacted prior to the first appointment and preventive measures discussed. Finally, the AMI patient with continuing serious post-infarction complications, e.g., severe heart failure, unstable angina will need to be done as a medically monitored case no matter how long since the AMI occurred because of the continuing high risk of reinfarction and cardiac arrest. The patients medical practitioner therefore must be consulted before any treatment is considered. REFERENCES

1. Chapman PJ. Medical emergencies in dental practice and choice of emergency drugs and equipment: a survey of Australian dentists. Aust Dent J 1997;42:103-108. 2. Girdler NM, Smith DG. Prevalence of emergency events in British dental practice and emergency management skills of British dentists. Resuscitation 1999;41:159-167. 3. Atherton GJ, McCaul JA, Williams SA. Medical emergencies in general dental practice in Great Britain. Part 1: Their prevalence over a 10-year period. Br Dent J 1999;186:72-79. 4. Jowett NI, Cabot LB. Patients with cardiac disease: considerations for the dental practitioner. Br Dent J 2000;189:297-302. 5. Chapman PJ. A case report of acute heart failure caused by a patient delaying taking his diuretic medication. Aust Dent J 2002;47:66-67.

Australian Dental Journal 2002;47:3.

6. Malamed SF, KS Robbins. Medical emergencies in the dental office. 5th edn. Minneapolis: Mosby, 2000: Ch 27-29. 7. Scully C, Cawson RA. Medical problems in dentistry. 4th edn. New Delhi: Wright, 1998:61-63. 8. Bochner F (ed). Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: AMH Pty Ltd, 2000:612-619. 9. Fauci AS. Principles of Internal Medicine. 14th edn. Auckland: McGraw-Hill, 1998: Ch 243. 10. Rees TD, Rose LF. Periodontal management of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol 1996;67:627-635.

11. Weaver T, Eisold JF. Congestive heart failure and disorders of the heart. Dent Clin North Am 1996;40:543-561.

Address for correspondence/reprints: Dr PJ Chapman School of Dentistry The University of Queensland 200 Turbot Street Brisbane, Queensland 4000

Australian Dental Journal 2002;47:3.

261

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- BPJ 39 Angina Pages 38-47Documento10 pagineBPJ 39 Angina Pages 38-47ger4ld1nNessuna valutazione finora

- Periodontics يرﻛﺷ ﺎﮭﻣ د: Periodontal management of medically compromised patientsDocumento8 paginePeriodontics يرﻛﺷ ﺎﮭﻣ د: Periodontal management of medically compromised patientsYehya Al KhashabNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing and managing chest pain in primary careDocumento8 pagineAssessing and managing chest pain in primary careVictoria GomezNessuna valutazione finora

- Management of Patients With Compromising Medical ConditionsDocumento20 pagineManagement of Patients With Compromising Medical ConditionsAbdulSamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Course Task CU2Documento3 pagineCourse Task CU2Camille MactalNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Coronary SyndromeDocumento41 pagineAcute Coronary SyndromeAbdulhameed MohamedNessuna valutazione finora

- RNPIDEA-Coronary Artery Disease Nursing Care PlanDocumento8 pagineRNPIDEA-Coronary Artery Disease Nursing Care PlanAngie MandeoyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Management of CAD and ACSDocumento9 pagineNursing Management of CAD and ACSfriendofnurse100% (4)

- Planning and GoalsDocumento3 paginePlanning and Goalsali sarjunipadangNessuna valutazione finora

- How to rapidly respond to chest painDocumento3 pagineHow to rapidly respond to chest painPamela laquindanumNessuna valutazione finora

- Management of Medical Emeregency in Dental PracticeDocumento51 pagineManagement of Medical Emeregency in Dental Practicechoudharyishita163Nessuna valutazione finora

- Week 2 - Ms1 Course Task - Cu 2Documento3 pagineWeek 2 - Ms1 Course Task - Cu 2jaira magbanuaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dental care considerations for patients with heart diseaseDocumento24 pagineDental care considerations for patients with heart diseaseAli ahmed0% (1)

- Angina PectorisDocumento11 pagineAngina PectorisJohn Matley CaampuedNessuna valutazione finora

- Guidelines for thrombolysis in STEMIDocumento25 pagineGuidelines for thrombolysis in STEMIrranindyaprabasaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Intervention For Chest PainDocumento2 pagineNursing Intervention For Chest Painjhaden100% (3)

- Chest Pain Protocol in EDDocumento3 pagineChest Pain Protocol in EDshahidchaudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- Chest Pain Care PlanDocumento2 pagineChest Pain Care Planapi-545292605Nessuna valutazione finora

- Managing Chest Pain During Dental ExtractionDocumento15 pagineManaging Chest Pain During Dental ExtractionMahmoud TayseerNessuna valutazione finora

- Prehospitalresearch - Eu-Case Study 5 Antero-Lateral STEMIDocumento8 paginePrehospitalresearch - Eu-Case Study 5 Antero-Lateral STEMIsultan almehmmadiNessuna valutazione finora

- CHC-PC-0033: Procedure Number Version NosDocumento7 pagineCHC-PC-0033: Procedure Number Version NosQari Ramadhan AminNessuna valutazione finora

- Cardiovascular System Diseases Part 1Documento22 pagineCardiovascular System Diseases Part 1Prince Rener Velasco PeraNessuna valutazione finora

- Angina and MI Nursing Care ScenariosDocumento3 pagineAngina and MI Nursing Care ScenariosMaye Arugay100% (1)

- Managing Angina and Monitoring for MI ComplicationsDocumento3 pagineManaging Angina and Monitoring for MI ComplicationsGeraldine MaeNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Management 1. Approach ConsiderationsDocumento10 pagineMedical Management 1. Approach ConsiderationsYannah Mae EspineliNessuna valutazione finora

- Myocardial Infarction: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and ManagementDocumento2 pagineMyocardial Infarction: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and ManagementChris T NaNessuna valutazione finora

- Angina Types, Causes, SymptomsDocumento38 pagineAngina Types, Causes, Symptomsekhafagy100% (1)

- 2004 Core SeptDocumento147 pagine2004 Core SeptSana QazilbashNessuna valutazione finora

- 062 Cerebral-Challenge 5 Update 2011 PDFDocumento5 pagine062 Cerebral-Challenge 5 Update 2011 PDFcignalNessuna valutazione finora

- KillipsDocumento12 pagineKillipsNhorlyn Adante SoltesNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Coronary Syndrome - A Case StudyDocumento11 pagineAcute Coronary Syndrome - A Case StudyRocel Devilles100% (2)

- Cardiovascular Diseases 2Documento40 pagineCardiovascular Diseases 2Ali MuradNessuna valutazione finora

- Angina PectorisDocumento11 pagineAngina Pectorisjialin80% (5)

- Dental Treatment Fo Medical CompromisedDocumento43 pagineDental Treatment Fo Medical CompromisedWasfe BarzaqNessuna valutazione finora

- Presentation 3Documento42 paginePresentation 3Max ZealNessuna valutazione finora

- Managing Atrial Fibrillation 2015Documento8 pagineManaging Atrial Fibrillation 2015Mayra Alejandra Prada SerranoNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Scenario 1 - P3W1Documento4 pagineCase Scenario 1 - P3W1Chaz BayanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chest PainDocumento9 pagineChest PainIlyes FerenczNessuna valutazione finora

- Treating Dental EmergenciesDocumento15 pagineTreating Dental Emergenciesminaxi123Nessuna valutazione finora

- ACLS Secondary Survey For A Patient in Respiratory Arrest: BLS Arrest Figure 1. Basic Life Support Primary SurveyDocumento30 pagineACLS Secondary Survey For A Patient in Respiratory Arrest: BLS Arrest Figure 1. Basic Life Support Primary SurveyLusia NataliaNessuna valutazione finora

- ACS Case StudyDocumento26 pagineACS Case StudyMari Lyn100% (1)

- Acute Cardiac Pain Management GuideDocumento31 pagineAcute Cardiac Pain Management Guidejan100% (1)

- Chan, Johnson - TreatmentGuidelines PDFDocumento0 pagineChan, Johnson - TreatmentGuidelines PDFBogdan CarabasNessuna valutazione finora

- Managing Angina with Lifestyle ChangesDocumento7 pagineManaging Angina with Lifestyle ChangesLorrie SuchyNessuna valutazione finora

- Chest Pain Management NursingDocumento2 pagineChest Pain Management NursingJessica Koch100% (1)

- Nursing DiagnosisDocumento58 pagineNursing DiagnosisPrecious Santayana100% (3)

- Angina and MI Nursing CareDocumento2 pagineAngina and MI Nursing CareElaine Marie SemillanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Managing dental patients with cardiovascular diseasesDocumento54 pagineManaging dental patients with cardiovascular diseasesSafiraMaulidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Angina PectorisDocumento17 pagineAngina PectorisRacel HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- SOMBILLO Scenario 1 ANGINADocumento2 pagineSOMBILLO Scenario 1 ANGINAKarla SombilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Protocol 13: Chest Pain: A&E DoctorDocumento4 pagineProtocol 13: Chest Pain: A&E DoctorVanessa HermioneNessuna valutazione finora

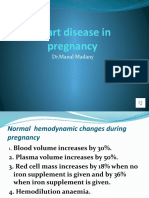

- Heart Disease in Pregnancy VoiceoverDocumento30 pagineHeart Disease in Pregnancy VoiceoverMohammed AbdNessuna valutazione finora

- Study Notes Emergency MedicineDocumento12 pagineStudy Notes Emergency MedicineMedShare57% (7)

- #3 Acs 6 PDFDocumento6 pagine#3 Acs 6 PDFOmar BasimNessuna valutazione finora

- What Symptoms Should Lead The Nurse To Suspect The Pain May Be Angina?Documento5 pagineWhat Symptoms Should Lead The Nurse To Suspect The Pain May Be Angina?Dylan Angelo AndresNessuna valutazione finora

- Caeserean DeliveryDocumento5 pagineCaeserean Deliveryapi-142637023Nessuna valutazione finora

- ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHY IN ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASEDa EverandELECTROCARDIOGRAPHY IN ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASENessuna valutazione finora

- MRCP(UK) and MRCP(I) Part II 200 CasesDa EverandMRCP(UK) and MRCP(I) Part II 200 CasesNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Surgical Topics: An Infographic GuideDa EverandAcute Surgical Topics: An Infographic GuideNessuna valutazione finora

- A Practical Guide to Common Presenting Complaints in Primary CareDa EverandA Practical Guide to Common Presenting Complaints in Primary CareNessuna valutazione finora

- Epithelial and connective tissue types in the human bodyDocumento4 pagineEpithelial and connective tissue types in the human bodyrenee belle isturisNessuna valutazione finora

- Ororbia Maze LearningDocumento10 pagineOrorbia Maze LearningTom WestNessuna valutazione finora

- Sexual Self PDFDocumento23 pagineSexual Self PDFEden Faith Aggalao100% (1)

- SEO-optimized title for practice test documentDocumento4 pagineSEO-optimized title for practice test documentThu GiangNessuna valutazione finora

- The Republic of LOMAR Sovereignty and International LawDocumento13 pagineThe Republic of LOMAR Sovereignty and International LawRoyalHouseofRA UruguayNessuna valutazione finora

- Lecture Notes 1-8Documento39 pagineLecture Notes 1-8Mehdi MohmoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Narasimha EngDocumento33 pagineNarasimha EngSachin SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Benchmarking The Formation Damage of Drilling FluidsDocumento11 pagineBenchmarking The Formation Damage of Drilling Fluidsmohamadi42Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Research TeamDocumento4 pagineThe Research Teamapi-272078177Nessuna valutazione finora

- Policy Guidelines On Classroom Assessment K12Documento88 paginePolicy Guidelines On Classroom Assessment K12Jardo de la PeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bible Study RisksDocumento6 pagineBible Study RisksVincentNessuna valutazione finora

- Crossing To The Dark Side:: Examining Creators, Outcomes, and Inhibitors of TechnostressDocumento9 pagineCrossing To The Dark Side:: Examining Creators, Outcomes, and Inhibitors of TechnostressVentas FalcónNessuna valutazione finora

- Crypto Portfolio Performance and Market AnalysisDocumento12 pagineCrypto Portfolio Performance and Market AnalysisWaseem Ahmed DawoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Medicalization of Racial Features Asian American Women and Cosmetic SurgeryDocumento17 pagineMedicalization of Racial Features Asian American Women and Cosmetic SurgeryMadalina ElenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Test Unit 3Documento2 pagineTest Unit 3RAMONA SECUNessuna valutazione finora

- The Other Side of Love AutosavedDocumento17 pagineThe Other Side of Love AutosavedPatrick EdrosoloNessuna valutazione finora

- Longman - New Total English Elementary Video BankDocumento26 pagineLongman - New Total English Elementary Video Bankyuli100% (1)

- Twin-Field Quantum Key Distribution Without Optical Frequency DisseminationDocumento8 pagineTwin-Field Quantum Key Distribution Without Optical Frequency DisseminationHareesh PanakkalNessuna valutazione finora

- Foundation of Special and Inclusive EducationDocumento25 pagineFoundation of Special and Inclusive Educationmarjory empredoNessuna valutazione finora

- 17 Lagrange's TheoremDocumento6 pagine17 Lagrange's TheoremRomeo Jay PragachaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pragmatic Marketing FrameworkDocumento2 paginePragmatic Marketing FrameworkohgenryNessuna valutazione finora

- Adina CFD FsiDocumento481 pagineAdina CFD FsiDaniel GasparinNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial MarketsDocumento323 pagineFinancial MarketsSetu Ahuja100% (2)

- BSC Part IiDocumento76 pagineBSC Part IiAbhi SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Nitrate Reduction in Sulfate Reducing BacteriaDocumento10 pagineNitrate Reduction in Sulfate Reducing BacteriaCatalinaManjarresNessuna valutazione finora

- Team Fornever Lean 8 Week Strength and Hypertrophy ProgrammeDocumento15 pagineTeam Fornever Lean 8 Week Strength and Hypertrophy ProgrammeShane CiferNessuna valutazione finora

- Software Security Engineering: A Guide for Project ManagersDocumento6 pagineSoftware Security Engineering: A Guide for Project ManagersVikram AwotarNessuna valutazione finora

- HCF and LCMDocumento3 pagineHCF and LCMtamilanbaNessuna valutazione finora

- Wjec Gcse English Literature Coursework Mark SchemeDocumento6 pagineWjec Gcse English Literature Coursework Mark Schemef6a5mww8100% (2)

- Islamic Finance in the UKDocumento27 pagineIslamic Finance in the UKAli Can ERTÜRK (alicanerturk)Nessuna valutazione finora