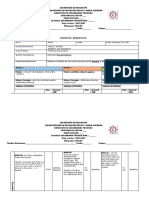

Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Byers, Sarah - The Meanina of Voluntas in Augustine

Caricato da

Diego Ignacio Rosales MeanaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Byers, Sarah - The Meanina of Voluntas in Augustine

Caricato da

Diego Ignacio Rosales MeanaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Augustinian Studies 37:2 (2006) 171-189

The Meaning of Voluntas in Augustine

Sarah Byers

Augustine uses the term voluntas for dispositional and occurrent forms of

horme of a rational being, horme being the Stoic concept of 'impulse' toward

action.

1

In what follows 1 shall first demonstrate this, using mainly books twelve

and fourteen of the De Civitate Dei. There is need of such a demonstration,

for although much ink has been spilt over the sense of "will" in Augustine's

texts, interpretations have varied greatly. Next 1 shall draw attention to a num-

ber of corroborating texts from works spanning thirty years of his writing

career, highlighting how this Stoic concept, together with Stoic epistemology,

makes sense of the uses of voluntas in book eight of the Conlessiones and of

'free will' (libera voluntas, liberum arbitrium voluntatis) in the De Libero

Arbitrio. 1 conclude with suggestions about specific texts and authors influ-

encing Augustine's usage.

Recent Interpretations

Gerard O'Daly has sometimes seemed very c10se to identifying Augustine's

voluntas with Stoic horme, but has not actually done so. In Augustine's Phi-

losophy 01 Mind, he once calls will "impulse,"2 but nowhere mentions the Stoic

concept of "impulse" as a psychic prompt toward action. Moreover, he does

l. See B. Inwood, Ethies and Human Aetion in FArly Stoicism (Oxford: Clarendon. 1985). 20, 53,

and passim.

2. G. O'Oaly, Augustine 's Philosophy 01 Mind (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California

Press. 1987) 26. Again he eomes cJose to identifying appetitus (whieh he identifies wltb "im-

pulse," p. 90) witb voluntas: "Augustine speaks ... of appet;tus and amor, and he also talks in

this connection [se. in eonnection with the eontext of paying attention) of!he voluntas and !he

intentio of !he mind" (211).

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

not provide a c1ear statement of what he takes "will" to mean. Thus the same

instance of "will" in one of Augustine's texts is called both "impulse" and an

"impulsive tendency;"3 he elsewhere refers to "the will as the motor of im-

pulses," 4 and at other times seems to think of vo/untas as a faculty of consent

which generates impulse, or a capacity for impulse that is activated conse-

quent to consent. 5

Others have asserted that Augustine's vo/umas owes much to Stoicism or to

the notion of horme. They have not, however, unreservedly identified vo/untas

as a translation for this Stoic concept, provided detailed textual demonstrations

for their c1aims, or reserved it, in every case, for impulse which is rational.

Thus Rist has said that Augustine was influenced by Seneca, who used vo/untas

for horme, but, he continues, Augustine's voluntas is a philosophical alterna-

tive to Stoic horme because Augustine enriched the 'Stoic theory by introducing

the Platonic element of eros.

6

Gauthier has asserted that ofthe traits ofthe "will"

which are found in Augusti ne, all were already present in the Stoics; but Gauthier

does not see vo/untas as a term specifically for the horme of a rational being.

7

Holte and Bochet are notable examples of scholars writing prior to the pub-

lication of Inwood's 1985 book on Stoic action theory;8 apparently they did not

have enough information about horme to recognize it in Augustine. In 1962

Holte identified Augustine's appetitus with Stoic horme, which he defined sim-

ply as a natural tendency; he also made the separate observation that Augustine

3. O'Daly, 26.

4. Ibid. 53 n. 144.

5. Ibid. 25, 89.

6. J. Rist, "Augustine: Freedom, Love, and Intention," in 11 Mistero del Male e 1<1 Libenil Possibile

(IV): Ripensare Agostino. Studia Ephemeridis Augustinianum, 59 (Rome: Institutum Patristicum

Augustinianum, 1997), 14-18; cf. Augustine: Ancient Thought Baptized (Cambridge: Cambridge

UP, 1994) 186-188. While 1 agree wth Rst that Platonc eros has a central role, 1 thnk that eros

and horme remain two distinct concepts with distinct functions in Augustine's theory of action.

For Augustine's use of Seneca more generally, see S. Byers, "Augustine and the Cognitive Cause

of Stoic Preliminary Passions' (P ropalheiai);' Joumal of the H istory of Philosophy XLI/4 (2003)

433-448; 434 n. 5, 436 n. 24, 446-448.

For eros in the Stoics, see recently M. Graver, Cicero on the Emotions: Tusculan Disputations 3

and 4 (Chicago: Unversity of Chicago Press, 2(02), 174-176 and the interesting remarks of J.

Rist. "Moral Motivation in Plato. Plotinus. Augustine, and Ourselves" in Plato and Platonism

(Washington: Catholic U. Press, 1999),261-277; 270-271.

7. R.-A.Gauthier. L'thique a Nicomaque 1./. (Publications Universitaires: Louvain. 1970) 259;

262.

8. See note l.

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

used vol untas to refer to "conscious impulse giving rise to action.'>9 Because he

did not realize that Stoic horme, as a tendency or disposition, tends toward ac-

tion, nor that the Stoics spoke of an occurrent sense of horme as well as a

dispositional sense, he did not see that Augustine's voluntas was the same as

horme, In 1982, Bochet similarly identified appetitus with horme, but actually

asserted that for the Stoic horme is a natural tendency without a specific orlen-

tation toward action.

1o

Thus although she noticed both occurrent and dispositional

uses of voluntas in Augustine,1I noticed that voluntas in Augustine pertains to

action, and also noticed that appetitus had both a dispositional and occurrenl

sense,12 she failed to identify voluntas either with appetitus or with horme.

A third group has asserted a vague connection between Augustine's volunta.!

andinclination or action; but their statements have not attempted to grapple witl1

the question of historical precedent for Augustine's usage. Thus Augustine's

vo/untas has been described as "a qualified tendency, mental attitude, lasting wish

, , . an inclination of the will" and "a volition, a specific act of Will,"13 a movemenl

of the soul tending to acquire or reject sorne object,14 and a word "which cover[ s 1

'choose,' 'want, 'wish,' and 'be willing."'15 More recently it has simply been note<l

that Augustine uses voluntas in connection withfacere.

16

Least convincingly of all, it has been asserted that Augustine invented tbe

modero notion of the will, which was not derived from earlier doctrines il1

philosophical psychology,I7 or that Augustine began but did not complete the

task of working out a Christian theory of the will that is in fundamental con

trast to classical Greek thought. 18 The texts do not bear this out.

9. R. Holte, Batitude el Sagesse (Paris: tudes Augustiniennes. 1962) 33, 201. 256, 283.

10. 1. Bochet. Saint Augustin et le Dsir de Dieu (Pars: tudes Augustinennes. 1982) 149. n. 5; cf

\05. n. 7.

11.lbid. 105-106.

12. Ibid. 150 n. 1.

13. N. Den Bok. "Freedom of the Will." Augustiniana 44 (1994).237-270; 255.

14. A.-J. Voelke. L'lde de Volont dans le Stoicisme (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1973

192.

15. C. Kirwan. Augustine (LondonINY: Routledge. 1989).85.

16. S. Harrison. "00 We Have a Wi11? Augustine's Way into the WiIl," in G. Matthews. OO., TIII.

Augustinian Tradition (Berke1eylLos AngeleslLondon: University of California Press. 1999)

195-205; see 199.

17. Earlier doctrines including Stoic horme; see A. Dible. The Theory ofWiII in Classical Antiquity

(BerkeleylLos Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1982) 123, 127, 134. 143.

18. C. Kahn. "Disovering the Wi11: From ArislOtle lO Augustine," in The Question of "Eclecticism n

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

Sorne Texts

Augustine explicitly mentions the Stoic concept horm in book nineteen of

the De Civitate Dei, where he tentatively translates it by impetus vel appetitus

actionis.

19

We see that he understands it as an impulse which does not need

reason in order to effect action, but which does reflect rationality in a healthy

human who is beyond the age of reason: "the insane say or do many absurd

things that are for the most part alien to their own aims and characters ...

horm ... is included among the primary goods of nature-is it not respon-

sible 1'or those pitiable movements and actions (jacta) 01' the insane that shock

us, when sensation is distraught and reason is asleep?"20

When he wants to refer specifically to the hormai of rational beings, he

uses voluntates. There is a heretofore overlooked "pfoo1' text" for this cIaim in

De Civitate Dei 5.9, which cIearly shows that by voluntas Augustine means

efficient cause of action, and that he thinks its proper sense is restricted to

rational beings, although it may be used for the horm/motus of animals in an

analogous sen se. lt runs as follows:

Human wills are the causes of human deeds ... voluntary causes [in gen-

eral] belong to God, or angels, or men, or animals-if those mots of animals

lacking reason, by which they do anything in accord with their nature, when

they either pursue or avoid sorne thing, are nevertheless to be called

vo/untates.

21

Studies in Latu Greek Phi/osophy, J. Dillon, ed. (Berkeley/Los AngeleslLondon: University of

California Press, 1988) 234-259; see 237.

19. De Civitate Dei (Hereafter civ.Dei) 19.4.: "Impetus porro vel appettus actions, si hoc modo

recte Latine appeIlatur ea quam Graec vocant hormen." The use of impetus or appetilus 10

translate horm . is Ciceroniano

20. Civ.Dei 19.4: "Phrenetici multa absurda ... dicunt vel faciunt, plerumque a bono suo proposilO

et moribus aliena ... hormen ... primis naturae deputant [Stoici] bonis, none ipse est, quo

geruntur etam insanorum iIli miserabiles motus et facta quae horremus, quando pervertitur

sensus ratioque soptur?" (For quotations from the civ.Dei, I have used but often adapted the

translations in the Loeb. Adaptalions are noted by reference 10 the name of the translator of the

volume; here Ihe translation is adapted from Greene.) Compare the Stoics per Inwood, Ethics,

112. Augustine refees to an age of reason in civ.Dei 22.24.

21. Civ.Dei 5.9: "Humanae voluntates humanorum operum causae sunt. ... lam vero causae

voluntariae aut Dei sunt aut angelorum aut hominum aut quorumque animalium, si tamen

voluntates appellendae sunt animarum rationis expertium motu s i11i quibus aliqua faciunt se-

cundum naturam suam cum quid vel adpetunt vel evitant." My trans., emphasis added.

174

I

r ......

'.

l ... ' ..

,

t

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

Moreover, as we are about to see, Augustine follows the Stoics in under-

standing impulse as having two forms: occurrent and dispositional.

22

According

to Augustine, each form has a corresponding object. An occurrent impulse is

directed toward performing sorne particular action concemed with the attain-

ment or avoidance of one intentional object. A dispositional impulse is directed

toward the set of actions by which one pursues the members of a kind of

object, that is, of an entire class of objects. Rational impulse comes in both of

these forms.

There is also scattered evidence that Augustine knew and was inluenced by

the Stoics' account of a particIuar kind of dispositional horm-'primary im-

pulse' toward self-preservation (prothorme), which the Stoics asserted was

present in all animals.

23

We hear echoes of this in the De Civitate Dei, the De

Libero Arbitrio, the In Epistolam Ioannis, and the Sermones, when Augustine

speaks of the voluntas humana, an innate drive to preserve one's own life, by

which man naturally "wills to live" (vivere vult)Y

A thorough demonstration of Augustine's indebtedness to the Stoic account

of horm, however, depends upon detailed textual work on three groups of

texts: De Civitate Dei XII and XIV, Confessiones VIII. and the De Libero

Arbitrio in conjunction with De Genesi ad Litteram IX and De Civitate Dei V.

1. The City of God Xll and XIV

Books twelve and fourteen of the De Civitate Dei are of the utmost impor-

tance because, with the exception of sections of book eight of the Confessiones,

no part of Augustine's corpus is as thick with references to voluntas. More-

over, they provide the key to unlocking Augustine's meaning in not only book

eight of the Confessiones, but the rest of his corpus as well. We need not be

concemed here with the ostensibly 'theological' context, which describes the

original sins of the fallen angels and of Adam and Eve. 25 For our purposes,

22. See Inwood, Ethics, 32, 45, and 224-225 with 229 on hexis hormliki.

23. See lnwood, Ethics, 19{}-193 and 218-223.

24. Ep./o.tr. 9.2.3, lib.arb. 3.6.18-3.7.21 (esse vis), civ.Dei 14.25, Sumo 299.8: "Amari mors non

potest, tolerari potest. ... Natura ergo, non tantum homines, sed et omnes omnino animantes

recusant mortem et formidant."

25. For philosophical currents, including Stoic ones, in Augustine's understanding of"faIlen-ness,"

compare Augustine, Enarrationes in Psalmos (hereafter En.Ps.) 30.2.13 and Confessiones (here-

after Conf.) 8.9.21-22, 8.11.26 to Seneca De Ira 2.\0.2,2.10.6, 2.13.\, and see N. J. Torchia,

Plotinus. Tolma. and the Descent of Being (New York: Peter Lang, 1993) 11-17.

175

Ocurrent

impulse: one

object.

Dispositional

impulse: a

set of

actions, a

class of

objects.

In absolute

disagreement

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTINE

the only important features of the context are that, as we have already seen,

Augustine included angels as well as humans in the category "rational," and

that by "sin" (peccatum) he meant an evil (internal or external) act.

In book twelve Augustine tries to account for sinful occurrent appetitus, 26

which for the time being I shall transliterate as 'appetite' so as not to beg the

question of whether it is indeed Stoic 'impulse.' He assumes that they must

arise out of (ex eo esse) preceding states of the soul-either the soul's nature

21

or an affectio, an accidental state of the soul by which it happens to be quali-

fied prior to the receipt of an impression (visum).28 Since the appetites in

question are sinful, he reasons that they cannot have their source in the na-

tures of souls as created (which must be good, since created by God). Their

sources must be acquired dispositions. He calls t ~ s dispositional roots of

occurrent appetite vo/untates or cupiditates:

It is not permissible lo doubt that the contrary appetitus of the good and

bad angels aros e not from differences in their original natures, since God,

the good author and creator of all forms of being, created both cIasses, but

from their respective vo/untares and cupiditates.

29

Augustine here plays on the word vo/untas as a translation of bou/esis, one

of the constantiae/eupatheiai predicated of the Stoic sage,30 in order to heighten

the contrast between the good and bad angels, emphasizing the depravity of

the demons by means of the more lurid "cupiditas."31 The vo/untas of the good

26. As Holte (Batitude 33, 201, 256, 283) and Bochet (Saint Augustin et le Dsir 150 n. 1) have

pointed out. Augustine does use appetitu.f for a tendency - by which I take !hem to mean a

disposition of!he soul to pursue certain things (for examples see Con! 10.35.54, the unspeci-

fied appetite to know, and en.Ps. 118,11.6. where he explains pleonexia as a habit by which

someone appetit more !han is enough); at least in book twelve of civ.Dei, however, Augustine

consistently uses it foc occurrent appetites.

27. Civ.Dei 12.6.

28. E.g. see the discussion of visum and affectio at 12.6; Augustine uses affectio foc a quality of the

body or the soul (e.g. "eadem fuerat in utroque corporis et animi affection," civ.Dei 12.6). Cf.

Cicero Tusculanae Disputationes (hereafter TD) 4.29, 4.30, 4.34 and De Inventione 1.36, 2.30,

wherein affectio is a more or less settled disposition, caBed habitus if more settled and weak-

ness or sickness (morbus) if less settled.

29. Civ.Dei 12.1: "Angelorum bonorum et malorum inter se contrarios adpetitus non naturis

principiisque diversis, cum Deus omnium substantiarum bonus acutor et conditor utrosque

creaverit, sed voluntatibus et cupiditatibus exstitisse fas non est." Trans. adapted from Levine.

30. TD 4.6.11-14.

31. Cf. civ.Dei 14.7: "idiomatic usage has brought it about (hat if cupiditas and concupiscentia are

used without any specification of !heir object, !hey can be taken only in a bad sense." Cf. G.

176

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTINE

angels is persistent, holy, and tranquil;32 the cupiditas of the demons is arro-

gant, deceitful, envious-in a word, it is "impure."33 Yet the impure cupiditas

of the demons is also persistent;34 it is a disposition.

In the surrounding text, however, this cupiditas also goes by the name of

vo/untas. He identifies the demons' cupiditas with vo/untas perversa,35 using

vo/untas for a vicious condition ofthe soul (e.g. civ.Dei 11.17: vitium malitiae

... vo/untas ma/a).36 Elsewhere, too, vo/untas is applied to bad, as well as

good, dispositions from which occurrent appetites ariseY Thus Augustine

consistently retains the sense of disposition and constancy that the word

vo/untas has in Cicero's use of it for Stoic bou/esis, but frequently drops the

association with virtue, only capitalizing on that association when he wants to

contrast the demons with the ange)s. The association is not a constant or even

a typical feature of his use of the word vo/untas.

Augustine describes these dispositional vo/untates or cupiditates as orien-

tations toward types of objects. The two societies of angel s are mirrored in the

two "cities" of men on earth; the bad human society is comprised of sub-

groups, with each group "pursuing the advantages and cupiditates peculiar to

itself."38 Thus we are dealng with dispositions to pursue classes of objects.

While occurrent appetites arise out of comparably stable states, these states

themselves result from an interior act of the rational soul. In the case of the

demons, Augustine calls this the act of "tuming away" (conversio) from the

Bonner, "Libido and Concupiscentia in SI. Augustine," Studia Patristica 6 (Texte und

Untersuchungen 81) (1 %2), 303-314.

32. Civ.Dei 11.33 "sancto amore ... tranquillam (societatem angelorum]", 12.1.11: "constanter",

"caritate Dei et hominum persistunt", 12.6: "voluntate pudica stabilis perseveret".

33. Civ.Dei 11.33: "inmundo amore fumantem (societatem angelorum)".

34. Their having cupiditas is synonymous with their having acquired certain character traits: "superbi

fallaces invidi effecti sunt," a state comparable to caecitas (civ.Dei 12.1).

35. Civ.Dei 11.33.

36. Again Augustine's voluntas is like Cicero's affectio; for the identification of affectiones with

vitia, TD 4.29, 4.34. Cf. civ.Dei 12.6: "voluntatem malam ... ipsa quia facta es!, adpetivit."

37. Cf. civ.Dei 11.17-12.9 passim, e.g. 12.3: "inimici enim sunt resistendi voluntate", 12.6: "aut

habet aut non habet aliquam voluntatem; si habet, aut bonam profecto babet aut malam .... Erit

enim, si ita es!, bona voluntas causa peccati, quo absurdius putari nihil potest.", 12.9: "sine

bona voluntate, hoc est dei amore, numquam sane tos angelos fuisse credendum est:' Cf. also

Con! 8.5. \O: "ex voluntate perversa libido."

38. Civ.Dei 18.2, "utilitates at cupiditates suas quibusque sectantibus." Trans adapted from Sanford

and Green.

177

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

object of their previous, good will.

39

The first vicious disposition arose in these

angel.s they "sank:" by a "spontaneous lapse," from their glorious

state mto a vltlated state; thls lapse was a discrete psychic event in which they

began to prefer a new class of goods.

40

. Similar to this account is the description of Adam and Eve's original sin

m book fourteen. In order to explain an occurrence (in this case, an external

rather than an appetitus), Augustine again posits a preceding disposi-

He that there must have been a foregoing vicious state of soul,

he agam calls a vo/untas (praecessisset vo/untas ma/a),41 in order to

how Adam and Eve's performance of the evil deed, eating from the

forbtdden could .have occurred. The contrast he invokes is clearly one

?etwee.n dOl.ng and bemg: "the evil act (opus), i.e.! the transgression involv-

mg thetr eatmg the forbidden fruit, was committeJby those who were already

bad. For only abad tree [disposition] could have produced that evil fruit

[the As in the case of the angels, this disposition is also said to

have ongmate?, The bad tree is a "vo/untas which had grown

dark and cold, a vltlatlOn of the original nature of man. 43 This vo/untas

mala had its beginning (initium) in an act of "defection" from or "desertion"

of the .good sought beforehand.

44

The defection was an appetitus for self-

exaltatlOn.

43

lt is clear throughout both of these books, and throughout his corpus that

Augustine think.s the origi.nal sins of the angel s and humans were

the a turnlng away from God by rational creatures, through pride. Thus

the turnlng away" (conversio) of the good angels who became bad is the

sort of psychic event as the "defection"-i.e., appetitus-of the human

palr who also a:-v.ay. in both cases, an occurrent appetite preceded

and caused a dlsposltlOnal wlll (appetitus -+ vo/untas).

39. Cv.De 12.6.

40. "defluxerunt," civ.Dei 12.1; "a bono sponte deflcit," cv.Dei 12.9.

41. Civ.De 14.13.

42. Civ.Dei 14.\3: ."Non ergo malum opus factum est, id est iBa transgressio ut cibo prohibilo

OISI ab els qUI lam mah eran!. Neque enim fleret ilIe fructus malus nisi ab arbore

mala. Trans. adapted from Levme.

43. Civ.De 14.13.

44. "des.eruit," civ.De 13.15; civ.Dei 14.11: "defectus ab opere Dei ad sua opera'" . 1413'

"dehclt horno." , . el . .

45. Civ.Dei 14.13.

178

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

The case of Adam and Eve now differs from that of the demons only inso-

far as it seems to jump from a dispositional vo/untas to an external action

(vo/untas -+ opus), whereas the demons' disposition was said to yield occur-

rent appetite (vo/untas -+ appetitus). However, if Augustine holds that an

occurrent appetite is necessary for the doing of any external deed, we will

need to insert an appetitus between the humans' disposition (vo/untas) and

act (opus). Then the psychological progression would be the same for the

human pair as for the demons, up until the point of the opus which com-

pletes the series (appetitus -+ vo/untas -+ appetitus-+ opus). In fact, there is

every reason to think that Augustine would insert an appetitus here. He con-

stantly describes action as effected by a preceding appetitus actionis.% Thus

the psychology of action operating in the human pair should indeed be de-

scribed as:

appetitus -+ vo/untas -+ appetitus -+ opus

occurent -+ disposition -+ occurrent -+ external act

What is most interesting, however, is that the first and third elements in

this sequence also go by another name: vo/untas. Augustine repeatedly refen

to the efficient cause of an action (the third element) as a vo/untas (most ex

plicitly, mala vo/untas causa efficiens est operis mali, civ.Dei 12.6) wher

speaking of the demonsY He also refers to the initial turning away or defeco

tion (the first appetitus in the series) as a vo/untas: "the first evil vo/untas ..

was a falling away (defectus)."48 In other words, we find the following:

vo/untas -+ vo/untas -+ vo/untas -+ opus

occurrent -+ disposition -+ occurrent -+ external act

An orientation toward action runs through the whole of this psychologica

sequence. The third vo/untas in the series is a causa efficiens operis, als{

known as appetitus actionis, as we have already seen. The first vo/untas is a:

well, for Augustine says that this occurrent vo/untas, the appetitus for per

verse self-exaltation which was the defection, was "a falling away from th!

46. See esp. Con! 13.32.47, Con! 2.9.17, Con! 10.20.29, De Trinitate (hereafter trin.) 9.12.IE

10.2.4, 11.2.2, 11.1 \.18, 12.13.21, 15.26.47, En.Ps. 74.3, Ad Simplicianus (hereafter Simpl.

2.4, cv.Dei 14.18, 14.26,22.22.

47. Cf. cv.Dei 5.9: "bumanae voluntates humanorum operum causae sunt," cv.Dei 12.6.15: "qui

est enim quod facit voluntatem malam, cum ipsa faciat opus malum?" In trino 9.12.18 occurrer

appetitus and va/untas are interchanged, as they are at trino 15.26.47.

48. Civ.dei 14.11; cf. 12.6, passim.

179

Impulso (appetitus), Disposicin

(voluntad), voluntad o ejecucin

(voluntas)

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

work (opere) of God to the will's own works (opera)."49 And as shown earlier,

tile dispositional voluntas, or second item in the series, is a disposition toward

pursuing (sectari) goods of the c1ass toward which one is oriented. Thus oc-

current and dispositional vo/untates are, for Augustine, occurrent and

dispositionaJ forms of appetitus actionis.

Since Augustine translates the Greek horme by appetitus actionis, and since

the Stoics spoke of both an active and a dispositional form of horme, it is

quite reasonable to conc1ude that in these texts he is using vo/untas as a trans-

lation for Stoic horme.

2. Conjessiones VIII

Turning to Conjessiones book eight, we find of our theory,

and discover additional Stoic features of his usage. When he famously de-

scribes how he was divided between "voluntates, "50 also called "parts of

voluntas," he relies on the concept of dispositional horme. He recounts:

My two wills ... were in conflict with one another, and their discord robbed

my soul of all concentration.

51

So there are two wills. Neither of them is complete, and what is present in

the one is lacking to the other.

52

A will half-wounded, struggling with one part rising up and another part

falling down ... 5.1

These wills or 'parts' of will are dispositions to pursue distinct c1asses of

goods, and have been formed by habitual actions, as he says: "my two

vo/untates, one old, the other new ... were in conflict with one another .... 1

was split between them .... But 1 was responsible for the fact that habit (con-

suetudo) had beco me so embattled against me."54 One "will" tends toward a

49. Cil'.dei 14.11. "Mala yero voluntas prima ... defectus ... fui! quidam ab opere Dei ad sua

opera."

50. In additon to lhe following passages. see Conf. 8.10.24.

51. Conj. 8.5.10: "duae voluntates meae ... conflingebant nter se atque discordando dsspabant

anlmam meam." For translatons of the Confessions 1 have used but often adapted (as noted) H.

Chadwck. Conjessms (OxfordlNew York: Oxford UP, 1991).

52. Conj. 8.9.21: "ideo sunt duae voluntates. quia una earum tota non est et hoc adest alteri quod

deest al teri" ,

53. Conf 8.8.19: "Semisauciam ... voluntatem parte adsurgente cum alia parte cadente luctantem"

Trans. adapled from Chadwick.

54. Con! 8.5.10-11: "Ita duae voluntates meae. una vetus, ala nova ... conflingebant inter se ....

Sed lamen consuetudo adversus me pugnacior ex me facta erat."

180

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

sensual lifestyle and has been forged by his habitual relations with women;55

the other tends toward a celibate life and has been formed by repeated musing

on the philosophical ideal of study and on biblical exhortations to the unmar-

ried state, as well as by frequenting (jrequentare) the church.

56

Voluntates are also occurrent impulses toward particular acts in this book.

Augustine indicates that the repeated actions which had built up his disposi-

tional voluntates had each been preceded by the occurent willing of individual

actions: "1 was responsible for the fact that habit (consuetudo) had become so

embattled against me, since it was [by] willing (volens) that 1 had come to be

where [Le., in the state which] 1 did not [now] want [any longer]."51 Later, too,

the assumption underlying his usage is that the efficient causes of individual

actions are occurrent vo/untates. He explains that when one deliberates be-

tween going to the theater or going to church, there are "two wills quarreJling

with one another."58 Similarly,

both vo/untates are evil when one is deliberating whether to kill a person by

poison or [to kili] by a dagger; whether to encroach on one estate belonging

to someone else or [to encroach on] a different one ... whether to buy plea-

sure by lechery or avariciously to keep his money; whether to go to the circus

or [to gol to the theater ... or ... to steal ... or ... to commit adultery.59

Again, the wills are good when one is deliberating whether "to take delight

in a reading from the apostle ... to take delight in a sober psalm ... [or] te

discourse upon the goSpel."60 Augustine makes explicit that these wiJls, 01

occurrent impulses to act, are each aimed at attaining one intentional object:

"They tear the mind apart by their mutual incompatibility-four or more wills

according to the number of things desired."61

3. De Libero Arbitrio, De Genesi ad Litteram IX, ami De Civitate Dei V

Finally, Stoic action theory and epistemology helps to c1arify the

of Augustinian "free will," the phrase often used to translate

55. See Conj. 6.15.25-6.16.26, 8.11.26; ef. 8.10.24 ifamiliaritate).

56. See Conj. 6.12.21-22, 6.14.24, 8.6.13, 8.1.2.

57. Con! 8.5.11: see the later part of note 52, "quoniam volens quo nollem perveneram."

58. Conf. 8.10.23: "Si ergo quisquam ... altereantibus duabus voluntatibus fluetuet, utrum a(

theatrum pergat an ad eeclesam nostram."

59. Conj. 8.10.24.

60. Conj. 8.10.24. Trans. adapted from Chadwiek.

61. Conf. 8.10.24: "discerpunt enim animum sibimet adversantibus quattuor voluntatibus vel etian

pluribus in tanta eopia rerum, quae appetuntur." Trans. adapted from Chadwick.

181

Voluntas como

causa efficiens

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTINE

arbitrium valuntatis, liberum arbitrium valuntatis, and libera va/untas. lt is

evident that he does not mean by these terms to refer to a faculty of uncaused

willing, since he agrees with the Stoics that every event has an efficient cause.

62

And he does not usually use them to refer to a faculty, although there are

occasions when libera valuntas and valuntas are described as a faculty, as we

shall see.

a. (Liberum) Arbitrium Valuntatis

We begin with the phrase arbitrium valuntatis. The Stoics asserted that hu-

man impulse is preceded by assent to a passively received hormetic impression.

63

They contrasted this with the case of non-rational animals, which lack the power

of assent;64 in these, impulse simply follows such impressions. If Augustine is

deeply indebted to Stoicism for his notion of valuffias, we would expect that

when he uses the phrase arbitrium valuntatis he is being somewhat redundant,

using arbitrium to stipulate in what way valuntas is specifically rational harme-

namely that it is harme which follows on assent (choice, arbitrium). Augustine

might feel the need to spell this out, given that we have seen him allowing the

term valuntas to be used of irrational impulse in an extended, non-technical

sense.

65

Valuntatis, then, would be an objective genitive stipulating that the

kind of assent in question is assent to a hormetic impression, which yields

impulse. In this sense, one's having a will is one's own responsibility and is

chosen, though not directIy so, since the object of assent is the impression.

66

Our expectation is met in a number of texts. In De Genesi ad Litteram

9.14.25, while making epistemological cIaims that cIearly show his debt to

Stoicism, Augustine interchanges arbitrium with iudicium and associates these

with valuntas in order to distinguish the impulse of rational beings from that

of any living creature, which he calls appetitus:

62. See e.g. civ.Dei 5.9, where he argues againsl Cicero: "The concession Ihal Cicero mues, Ihal

nOlhing happens unless preceded by an efficienl cause (causa ejficiens), is enough lo refule

him in Ihis debale [with lhe Stoics) .... It is enough when he admits Ihal everylhing Ihal hap-

pens. happens only by virtue of a preceding cause (causa praecedente)."

63. See Inwood. Ethics. 55

64. See Inwood. Elhics. 44.

65. Civ.Dei 5.9, ciled aboye.

66. Similarly C. Kirwan, allhough wilhout reference to Ihe Sloic background and wilhout stipula-

tion thal arbitrium understood as assenl is the real locus of this 'freedom': "When he [i.e.

Augusline) does say Ihal Ihe human will is free (e.g. De Duabus Animis 12.15), he usually

mean s, 1 think, Ihal men are free whether or nOI to exercise their wills - to engage in Ihe activity

of willing" (Augusline, 86).

182

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

For every living soul, not only rational, as in men, but also irrational, as in

beasts and birds and fish, is moved by impressions. But the rational soul

either consents to the impressions or does not consent, by a choice which

generates impulse: but the irrational [soul] does not have this judgment;

nevertheless in accordance with its nature ir is propelled once having been

affected by sorne impression. And it is not in the power of any soul which

impressions come to it, whether [they come to it] in the bodily sense or in

the interior spirit itself [Le., the imagination]: [but in all cases it is true that]

by such impressions the impulse of any animal is activated.

67

Since the judgment (iudicium) referred to is identified as consent

(consentire) or refusal of consent to an impression, we know that the

"choice" (arbitrium) which is given as its synonym is a choice between the

options of mentally asserting that the impression is accurate, or asserting

that it is falseo

This phrase arbitrium voluntatis also occurs in De Civitate Dei 5 when

Augustine argues for the Stoics, against Cicero, that God's foreknowledge is

compatible with what he calls arbitrium voluntatis; and it again shows

Augustine's Stoic patrimony. He summarizes the philosophical challenge posed

by Cicero in the De Fato

68

thus:

If all future events are foreknown ... the order of causes is fixed (certus est

ordo causarum) . ... If this is the case, there is nothing really in our power,

and there is no rational impulse (nihil est in nostra potestate nullumque est

arbitrium voluntatis). And if we grant this, says Cicero, the whole basis of

human life is overthrown: it is in vain that laws are made, that men employ

reprimands and praise ... and there is no justice in a system of rewards for

the good and punishment for the bad.

69

The phrase arbitrium voluntatis is Augustine's addition to Cicero's text;

he gives it as a synonym for Cicero's phrase in nostra potestate (eph 'hemin).

lt becomes cIear that Augustine understands the voluntas in this phrase t(]

67. "Omnis enim anima viva, non solum rationalis, sicut in hominibus, verum etiam irrationalis

sicut in pecoribus, et volalilibus, et piscibus, visis movetur. Sed anima rationalis voluntati!

arbitrio vel consentit visis, vel non consenti!: irrationalis aulem non habet hoc iudicium; prc

suo tamen genere atque natura viso aliquo tacta propellitur. Nec in potestate uIlius animae est

quae iIIi visa veniant, sive in sensum corporis, sive in ipsum spiritum interius: quibus vis!

appetitus moveatur cuiuslibet animantis." My transo

68. Attributed to the veleres. See De Falo (hereafter DF) 40.

69. Civ.Dei 5.9: "Si praescita sunt omnia futura ... certus est ordo causarum .... Wuod si ita est

nihil est in nostra potestate nullumque est in arbitrium voluntatis; quod si concedimus, inquit

omnis humana vita subvertitur, frustra leges dantur, frustra obiurgationes laudes ... neqU\\

ulla iustitia bonis praemia et malis supplicia constituta sunt." Trans. adapted from Green.

183

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

mean hormelappetitus. and that arbitrium is a reference to assent. when we

consider the original passage from De Fato 40 whch he is summarizing. lt

says: I.f an impression received from the outside is the cause of impulse

(appetltus), assent (assensio) or action (actio), then these are not in our power

(in nostra potestate), in which case there is no justice in rewards and pun-

ishments.

70

Thus Augustine intends to sum up in one phrase (nihil est in

nostra potestate nullumque est arbitrium voluntatis) the linkage between

concepts (appetitus, assensio, and in !lostra potestate) that Ccero estab-

lishes over the course of two sentences.

. In the follow.ing paragraphs of De Civitate Dei 5.9, Augustine repeatedly

mterchanges thls voluntatis arbitrium with other phrases. One of these is

where.liberum be.applied for empha-

SIS, the Idea bemg that smce assent IS by defimtlOn a choIce between options

(to approve or not approve an impression), it is therefore necessarily 'free.' 71

Augustine goes on to describe voluntas itself as "in our power" rather than

"necessary"-i.e., to assert that it is free: "If the term 'necessity' should be

used of what is not in our power (non est in nostra potestate), but accom-

plishes its end even against our will (etiamsi nolimus), for example, the

nece.ssity. of death, then it is clear that our wills (voluntates nostras), by which

we hve nghtly or wrongly, are not under such necessity."72 The basis for this

truism is the fact that arbitrium precedes human impulse;73 it makes human

impulse by definition "free" or "in our power."

When Augustine defends the justice of God's punishments in the De Libero

Arbitrio, he also associates voluntas with liberum arbitrium, and again Stoic

and action-theory are at work. Voluntas is said to be a necessary

condltlOn for acts to be evaluated morally-"no action would be either a sin

or a good deed which was not done voluntate"74-and it is interchanged with

in libero arbitrio. Thus we find:

70. DF 27.40.

71. See also lib.arb. 1.16.34-35 for the interchange of elige re and Liberum arbitrium: "quid autem

qUisque sectandum et aplectandum eligat in voluntate esse positum constitit ... id faciamus ex

libero arbitrio ... Iiberum arbitrium, quo peccandi facultatem habere convincimur."

72. Civ.Dei 5.10.

73. he asserts Ihat it is necessary (by defnitin) Ihat "when we will, we will by free choice"

( dlclmus necesse esse, ut cum volumus, libero velimus arbitrio" (civ.Dei 5.10). This is!he reason

why at civ.Dei 5.10 we hear Ihat va/untas cannot exist, except as !he va/untas oflhe one who wi11s

and not of anolher person (nee alterius. sed eius); wi1l by definition belongs to the one who wills:

For other texts assertmg Ihat one eannot be compelled to will, see Rist, Augustine, 134 and 186.

74. Lib.arb. 2.1.3.

184

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

The first man could have sinned even if he were created wise; and since that

sin would have been a matter of free choice (quod peccatum cum esset in

/ibero arbitrio), it would ha ve been justly punished in accordance with di-

vine law .... The transitions between wisdom and folly never take place

except through will (numquam "isi per voluntate), and for this reason they

are followed by just

Augustine goes on to explain why he has interchanged these two. Voluntas

is impulse rooted in the rational capacity of assent to impressions:

But since nothing incites will toward action except sorne impression,76

but whether someone either affirms or rejects lit] is in his power, but there

is no power [for him over whether] he is touched by this impression, it

must be acknowledged that the rational soul is affected by both superior

and inferior [kinds of] impressions, with the result that the rational sub-

stance chooses from either class what it wills, and by virtue of its choosing

either misery or happiness follows. For example, in the Garden of Eden

... man had no control over what the Lord commanded or what the devil

suggested. But it was in his power not to yield to the impressions of infe-

rior pleasure.

77

75. Lib.arb. 3.24.72-73: "Etiam si sapiens primus horno factus est potuisse tamen seduci, quod

peccatum cum esset in libero arbitrio, iustam divina lege poenam consecutam .... IIIa autem

numquam nisi per voluntatem, unde iustissimae retributions consecuntur." The "iIIa" here is a

reference to the frst man's fall from the pinnacle of wisdom to foolishness (ex arce sapientiae

ut ad stu/titiam primus hamo transire). Augustine adopts Ihe plural neuter to mean "the forrner

kind of aetion," which he eontrasts with passing from sleep to wakefulness and vice versa,

which he says is involuntary (sine vo/untate) and calls "ista." Trans. adapted from Wi11iams,

op. cit. For synonymous use of libera vo/untas and Iiberum vo/untatis arbitrium in Ihe Iib.arb.,

see e.g. 2.18.47.

76. On the necessity of foregoing impression, cf. Iib.arb. 3.25.75: "But from what source did the

devil himself receive the suggestion to desire the impiety (suggestum appetendae impietatis)

by which he fell from heaven? For if he were not affected by any impression, he would not

have ehosen to do what he did, for if something had not come to him. into his mind, in no

way would his attention have shifted toward wickedness .... For he who wills, clearly wills

somethng, which is either brought to one's attention from the outside Ihrough a bodily

sense, or comes into the mind in some obscure way; otherwise one cannot wiI1 (velle non

potest)." My trans.; emphasis added. Compare the Stoics, cited and diseussed by lnwood,

Ethies, 54.

77. Lib.arb. 3.25.74: "Sed quia voluntatem non aIlicit ad faciendum quodlibet nisi aliquod visum,

quid autem quisque vel sumat vel respuat est in potestate, sed quo viso tangatur nulla potestas

est, fatendum est et ex superioribus et ex inferioribus visis animum tangi ut rationalis substan-

tia ex utroque sumat quod voluerit et ex merito sumendi vel miseria vel beatitas subsequatur.

Velut in paradiso ... neque quid sibi praeciperetur a domino neque quid a serpente suggeretur

fuit in homine potestate. Quam sit autem ... non cedere visis inferioris i11ecebrae." My trans.,

except Ihe second to last sentence, which is Williams'.

185

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTINE

Plainly voluntas is here a rational being's impulse toward action, and to be

rational is to have the capacity to yield or not yield to impressions. As was the

case in the De Civitate Dei, this capacity is what prevents humans from being

necessitated; and by it God's justice in punishing human actions is saved. The

voluntary movement of soul (motus animi) by which all sin occurs is in our

power because it ineludes rejection or approbation of impressions; 78 and so

God does not cause everything he foreknows-rather, human beings are re-

sponsible for their acts.

79

b. Libera Voluntas

Thus far we have seen that Augustine calIs both arbitrium vo/untatis and

voluntas "in our power," and also makes the former synonymous with liberum

arbitrium vo/untatis in the De Civitate Dei. We hav't! observed. moreover, that

he interchanges in libero arbitrio with vo/untate in the De Libero Arbitrio. It

comes as no surprise, then, that elsewhere in the De Civitate Dei he substi-

tutes arbitrium voluntatis for vo/untate facere, for in nostra voluntate, ando

occasionalIy, for libera voluntas.!lO Moreover, when summarizing Cicero, he

uses in nostra vo/untate to stand in for Cicero's phrase in nostra potestate.

81

Apparently he considers it enough to say "in our impulse" (in nostra vo/untate)

or "to do by Lrational] impulse" (vo/untate facere) to indicate that an act is in

our power. given that assent has preceded. Thus libera vo/untas, arbitrium

vo/untatis, and /iberum arbitrium vountatis are synonymous, meaning 'ratio-

nal impulse which is by definition free.'82

When libera vo/untas occurs in the De Libero Arbitrio, it is sometimes

interchanged with vo/untas; both have a e1ear connection to action

83

and are

78. See also the passages on consent in De Mendacio 9.12-14 and De Sermo Domini in Monte

1.12.34; Ihese are discussed by C. Kirwan (without much use of the Stoic epistemology) in

"Avoiding Sin: Augustne and Consequentialism" in The Augustinian Tradilion, 183-194; see

186,190.

79. Lib.arb. 3.1.2-3.1.3 and 3.4.11.

80. Civ.Dei 5.9-10.

81. See civ.Dei 5.9. when summarizing what he takes to be the Ciceronian objeclion.

82. Similarly Rist, Augustine. 186 n. 91: "The phrase 'free will' (libera vo/untas) occurs rarely, if

at all, before Augustne, who might seem 10 use it merely as an alternative for liberum arbitrium

vo/untatis (/ib.arb. 3.1.1 )."

83. Libera vo/untas is "of asking, of seeking, of strving" ("Iiberam voluntatem petendi et quarendi

et conandi non abstulit [Creator]," /ib.arb. 3.20.), is onenled loward doing (adfaciendum) and

is acted "through" ("Video enim ex hoc quod incertum est, utrum ad recte faciendum voluntas

libera data sit, cum per illam eliam peccare possmus. tier eliam illud incertum, utrum dan

186

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTINE

linked to recognizable Latin terms for horme: voluntas libera "has motus."84

vo/untas is "tumed by motus,"8S and when people tum libera vo/untas toward

inferior things, they appetunt those inferior things.

86

Given that vo/untas and

libera vo/untas are interchanged, the libera again seems to have been em-

ployed for emphasis.

What is distinctive and non-Stoic about the phrase libera voluntas in the De

Libero Arbitrio is that it is sometimes used for a faculty (facultas) or power (po-

tentia) of the rational soul (animi)87-something given to man by the creator.

f18

which remains in us

89

regardless of whether we use it weIl or badly.90 Occasion-

alIy this capacity is also simply called vo/untas. Thus we find:

Libera vo/untas is a good, since no one can Iive rightly without it. ...

powers of the soul, without which one cannot Iive rightly, are intermediate

goods .... Vo/untas itself is only an intermediate good. But when voluntas

turns away from the unchangeable and common good toward its own private

good, or toward external or inferior things. it sins .... Hence the goods that are

debuerit"f "It is uncertain whether free will was given for aeting rightIy, since we can aIso sin

through it; eonsequentIy it is also uneertain whether it ought to have been given" (lib.arb.

Thus Ihe question is whether Ihe faeulty was given for aeling right/y as opposed to wrong/y, It

being assumed that Ihe faculty is onented toward aelion. Por this use of Ihe notion of faculty,

see below.

84. "Si ita data est vol untas libera ut naturalem habeat istum motum." (lib.arb. 3.1.1). (The question

here is whether va/untas libera by necessity has a sinful motus.) This translation and Ihose

following. unless otherwise noted, are (ofien adapted) from T. WiI1iams, On Free Choice of the

Will (Indianapolis: Haekett. 1993).

85. Lib.arb. 3.1.1 "Cupio per te eognoscere unde me motus existat quo ipsa voluntas aVerllUr a

eommuni atque ineommutabili bono."

86. Lib.arb. 2.19.53: "Ita tit ut neque IIa bona quae a peceantibus appetuntur ullo modo mala sint

neque ipsa vol untas libera ... sed malum sit aversio eius ab incommutabili bono et conversio ad

mutabilia bona."

87. "Debet autem. si aceepit voluntatem liberam et sufficientissimam facultatem" (/ib.arb.

"he is a debtor to God if he has reeeived [from Him] free wll and sufficient power [to wllI

good]"); "vol untas libera tibi videbitur nullum bonum. sine qua recte nemo vivit? ... potentiac

yero animi, sine quibus recte vivi non potest, media bona sunt" (lib.arb. 2.18.49-2.19.19.50).

88. Lib.arb. 2.1.I: "Debuit igitur deus dare homini Iiberam voluntatem;" Book Two assumes thal

/ibera va/untas is a thing in the soul; the question is whelher to count it as a

"utrum in bonis numeranda sit vol untas libera" (lib.arb. 2.3.7), "utrum expedm posslt: IOtel

bona esse numerandam liberam voluntatem" (/ib.arb. 2.18.47).

89. "Non nego ita necesse esse ... ita eum [Deum] praescire ut maneat tamen nobis voluntas Iibeni

atque in nostra posita potestate" (lib.arb. 3.3.8).

90. The intermediate goods, the powers of Ihe soul, can be used eilher well or badly (mediis ... nor

solum bene sed etiam male quisque uti potest" (lib.arb. 2.19.50.

187

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTINE

pursued by sinners are in no way evil things, and neither is libera volu1l1as

itself, which we found is to be counted among the intermediate goodS.

91

This usage of voluntas libera for a faculty is not common in Augustine's

corpus, though it is repeated as late as the De Gratia et Libero Arbitrio (in

426): "We always have free will, but it is not always good .... Our ability [to

will] is useful when we wilI [rightly]."92 The use of vo/untas alone for this

facuIty is even rarer; it is limited, 1 believe, to the passage just cited from De

Libero Arbitrio, where it is interchanged with libera vo/untas. In such cases,

he is usng vo/untas and vo/untas libera as shorthand ways of referrng to the

capacity for havng impulse that follows on assent; this reduces to the capac-

ity for assent, since assent is the distinguishing characteristic. Thus we are not

dealing with a 'voluntarist' faculty, in the sense of a capacity for a-rational

action, but a rational faculty of judgment or asseI1fto impressions.

The Question of Augustine's Sources

As we have seen, by vo/untas Augustine does not mean the virtuous person's

'good emotion' of reasonable desire (desire for real goods, viz. the virtues),

despite the fact that Cicero uses the word as a translation for this Stoic eupatheia

in the Tusculanae. Augustine uses voluntas for human horm generalIy, and

considered apart from affective feelings. Who, then, was Augustine's histori-

cal source for this usage?

Certainly another text of Ccero, the De Fato, is important. Vo/untas is

cIearly used for impulse n De Fato 5.9, when it is paired with appetitio, and

associated with acton: "10 sit and to walk and to do sorne thing."93 Later

(when summarzing Carneades

94

), Cicero exchanges the word voluntas for

91. Lib.llrb. 2.18.50-2.19.53.

92. 15.31: "semper est autem in nobis voluntas libera, sed non semper est bona .... Utile est posse.

cum volumus."

93. " ... nostrarum voluntatum atque appetlionum ... putat ne ut sedeamus qudem aut ambulemus

voluntatis esse ... sedere atque ambulare et rem agere aliquam."

94. On Ihe fact tbat Ihe Antiochan summaries of Stoic doctrine somet mes used by Ccero are

likely to be influenced by Ihe sceptical Academy. see G. Strker, "Academics Fghting Aca-

demics" in Asunt llnd Argument, edd. B. lnwood and J. Mansfeld (Leiden: Koninklijke Brll:

1997): 257-276,258. On the use e.g. of Antochus' Sosus for the presentation of Stoic episte-

mology in the Academiea. see J. GIueker, Antiochus llnd the Late Academy (Gottingen:

Vandenhoeck und Rupreeht. 1978) 58 n. 4 and 419, as well as "Pmbllble. Ver Simile, and

Relaled Terms" in Cicem the Philosopher, ed. J. G. F. Powell (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995):

115-143,133 n. 74.

188

I

t.

l

1

,

r

BYERS: VOLUNTAS IN AUGUSTlNE

"voluntary impulse of the rational soul" (motus animi thus

again we see that he ntends this word to refer to a specific kind of im-

pulse-rational impulse. Cicero also speaks of libera voluntas. He indicates

that this freedom is due to man 's rational capacity to assent, contrasting it

with necessitas fati and appropriating it to the mind (mens).96 Moreover he

presents the question of whether any action is "of wilI" (vo/untatis) as iden-

tic al to the questions (a) whether anything is in our power (in nostra

potestate), and (b) whether assent (assensio) is in our power,91 The as socia-

tion of these concepts is precisely what we found in Augustine.

Seneca is another Iikely source. If Rist is correct that Seneca used the word

voluntas for horme. then the suggestion that Augustine's notion of "will" was

influenced by Seneca must also be right;98 for it is cIear that Augustine knew

Seneca's moral treatises well and used at least sorne of them throughout his

life.

99

Other possible sources, unverifiable because inextant, inelude the first book

of the De Fato, which was devoted to assent,IOO handbooks of Greek phi lo-

sophical texts (in Latin translation) which Augustine is believed to have

owned,101 and Varro's De Philosophia, which Augustine is summarizing juSI

prior to mentioning horme in the De Civitate Dei.

102

95. DF 11.23 and 11.25.

96. DF9.20.

97. DF 27.40; ef. DF 5.9.

98. See note 6 aboye.

99. See ibid.

100. See DF 27.40.

101. See P. Courcelle, Late Latn Writers and ther Greek Sources, transo H. Wedeck (Cambridge

Harvard U. Press, 1969 (Original work published 1943)), 192-194: Augustine had a six-vol

ume eompendium of extraets from Greek philosophers (in a Latin translation). There has beel

debate about its autbor; Coureelle argues thal it was Celsinus, son-in-Iaw of Julian the Apos

tate (n. 201), despite the faet that Augustine ealls him Celsus in tbe De Haeresibus (CourceH

suggests tbat tbis is a memory lapse due 10 old age, n. 202).

\02. See 19.1, 19.4

189

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Dante - Dante - Monarchy-Cambridge University Press (1996)Documento65 pagineDante - Dante - Monarchy-Cambridge University Press (1996)Dima KhakhishviliNessuna valutazione finora

- 0Documento429 pagine0Lear NcmNessuna valutazione finora

- Dominican Theology at the Crossroads: A Critical Editions and a Study of the Prologues to the Commentaries on the Sentences of Peter Lombard by James of Metz and Hervaeus NatalisDa EverandDominican Theology at the Crossroads: A Critical Editions and a Study of the Prologues to the Commentaries on the Sentences of Peter Lombard by James of Metz and Hervaeus NatalisNessuna valutazione finora

- Agustin Guerra Justa PDFDocumento209 pagineAgustin Guerra Justa PDFBiblioteca Alberto GhiraldoNessuna valutazione finora

- "Every Valley Shall Be Exalted": The Discourse of Opposites in Twelfth-Century ThoughtDa Everand"Every Valley Shall Be Exalted": The Discourse of Opposites in Twelfth-Century ThoughtValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (1)

- The History of The History of Philosophy and The Lost Biographical TraditionDocumento8 pagineThe History of The History of Philosophy and The Lost Biographical Traditionlotsoflemon100% (1)

- Iconoclasm As A DiscourseDocumento28 pagineIconoclasm As A DiscourseVirginia MagnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pope John XXII - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento8 paginePope John XXII - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaabadurdNessuna valutazione finora

- Kepler's Exploration of Celestial MovementDocumento29 pagineKepler's Exploration of Celestial MovementAndreas WaldsteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Allin, Lias. The Augustinian Revolution in Theology. 1911.Documento244 pagineAllin, Lias. The Augustinian Revolution in Theology. 1911.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (1)

- Benardete PapersDocumento238 pagineBenardete Paperslostpurple2061Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dionysius Longinus - On The SublimeDocumento446 pagineDionysius Longinus - On The SublimenoelpaulNessuna valutazione finora

- Germain Grisez - (1965) The First Principle of Practical Reason. A Commentary On Summa Theologiae, 1-2, Q. 94, A. 2. Natural Law Forum Vol. 10.Documento35 pagineGermain Grisez - (1965) The First Principle of Practical Reason. A Commentary On Summa Theologiae, 1-2, Q. 94, A. 2. Natural Law Forum Vol. 10.filosophNessuna valutazione finora

- Some Manuscript Traditions of The Greek ClassicsDocumento44 pagineSome Manuscript Traditions of The Greek ClassicsrmvicentinNessuna valutazione finora

- The Politica of Justus Lipsius - Anne MossDocumento17 pagineThe Politica of Justus Lipsius - Anne Mossagustinvolco9827Nessuna valutazione finora

- Henry Chadwick Boethius The Consolations of MusicDocumento349 pagineHenry Chadwick Boethius The Consolations of MusicCristeaNessuna valutazione finora

- Commentary On Being and Essenc - Cajetan, Tommaso de Vio, O.P. - 5160Documento358 pagineCommentary On Being and Essenc - Cajetan, Tommaso de Vio, O.P. - 5160willerxsNessuna valutazione finora

- Ottoman Empire Textbook Provides Comprehensive OverviewDocumento3 pagineOttoman Empire Textbook Provides Comprehensive OverviewMuhammad AkmalNessuna valutazione finora

- Anti Fraternal Tradition in Medieval Literature SpeculumDocumento28 pagineAnti Fraternal Tradition in Medieval Literature SpeculumJennifer DustinNessuna valutazione finora

- Leopold Schmidt - The Unity of The Ethics of Ancient GreeceDocumento11 pagineLeopold Schmidt - The Unity of The Ethics of Ancient GreecemeregutuiNessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophical Psychology in Arabic Thoug PDFDocumento1 paginaPhilosophical Psychology in Arabic Thoug PDFMónica MondragónNessuna valutazione finora

- La Cohabitation Religieuse Das Les Villes Européennes, Xe-XVe SieclesDocumento326 pagineLa Cohabitation Religieuse Das Les Villes Européennes, Xe-XVe SieclesJosé Luis Cervantes Cortés100% (1)

- The Cult of Saint DenisDocumento4 pagineThe Cult of Saint DenisJames MulvaneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Via ModernaDocumento24 pagineVia Modernahudson1963Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vlachos, Law, Sin and DeathDocumento22 pagineVlachos, Law, Sin and DeathJohnNessuna valutazione finora

- Leibniz's AestheticsDocumento218 pagineLeibniz's AestheticsCaio GrimanNessuna valutazione finora

- The First Evil Will Must Be Incomprehensible A Critique of Augustine PDFDocumento16 pagineThe First Evil Will Must Be Incomprehensible A Critique of Augustine PDFManticora VenerandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hobbes UniversitiesDocumento29 pagineHobbes UniversitiesJosé Manuel Meneses RamírezNessuna valutazione finora

- CASTON v. - Aristotle's Two Intellects. A Modest Proposal - 1999Documento30 pagineCASTON v. - Aristotle's Two Intellects. A Modest Proposal - 1999Jesús Eduardo Vázquez ArreolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lingard's History of England Volume 1Documento609 pagineLingard's History of England Volume 1Irene RagonaNessuna valutazione finora

- Revisiting Pia DesideriaDocumento2 pagineRevisiting Pia DesideriaSandra Elena Dermark BufiNessuna valutazione finora

- Bossy J.-counter-Reformation and Catholic EuropeDocumento21 pagineBossy J.-counter-Reformation and Catholic EuropeRaicea Ionut GabrielNessuna valutazione finora

- Crowe - 1977 - The Changing Profile of The Natural LawDocumento333 pagineCrowe - 1977 - The Changing Profile of The Natural LawcharlesehretNessuna valutazione finora

- Medieval Philosophy: Key WordsDocumento11 pagineMedieval Philosophy: Key WordsRod PasionNessuna valutazione finora

- A Death He Freely Accepted Molinist Reflections On The IncarnationDocumento19 pagineA Death He Freely Accepted Molinist Reflections On The IncarnationtcsNessuna valutazione finora

- Bloch2009 Robert Grosseteste's Conclusiones and The Commentary On The Posterior AnalyticsDocumento28 pagineBloch2009 Robert Grosseteste's Conclusiones and The Commentary On The Posterior AnalyticsGrossetestis StudiosusNessuna valutazione finora

- White. Select Passages From Josephus, Tacitus, Suetonius, Dio Cassius, Illustrative of Christianity in The First Century. 1918.Documento216 pagineWhite. Select Passages From Josephus, Tacitus, Suetonius, Dio Cassius, Illustrative of Christianity in The First Century. 1918.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNessuna valutazione finora

- Job in Augustine Adnotationes in Iob and The Pelagian ControversyDocumento196 pagineJob in Augustine Adnotationes in Iob and The Pelagian ControversySredoje10Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mentary On The Metaphysics of Aristotle IDocumento501 pagineMentary On The Metaphysics of Aristotle ISahrianNessuna valutazione finora

- Bonaventure's Collationes on the DecalogueDocumento16 pagineBonaventure's Collationes on the DecalogueVictorNessuna valutazione finora

- Classical Western Philosophy: Introduction and OverviewDocumento9 pagineClassical Western Philosophy: Introduction and Overviewseeker890Nessuna valutazione finora

- Medieval Architects in ScotlandDocumento25 pagineMedieval Architects in Scotlandcorinne mills100% (1)

- Vdoc - Pub A Companion To RomanticismDocumento558 pagineVdoc - Pub A Companion To RomanticismCamilo Andrés Salas SandovalNessuna valutazione finora

- Irving Jennifer 2012. Restituta. The Training of The Female Physician. Melbourne Historical Journal 40. Classical Re-Conceptions, 44-56 PDFDocumento13 pagineIrving Jennifer 2012. Restituta. The Training of The Female Physician. Melbourne Historical Journal 40. Classical Re-Conceptions, 44-56 PDFAnonymous 3Z5YxA9pNessuna valutazione finora

- Schall Metaphysics Theology and PTDocumento25 pagineSchall Metaphysics Theology and PTtinman2009Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vico, Giambattista - First New Science, The (1725) (Cambridge, 2002) PDFDocumento367 pagineVico, Giambattista - First New Science, The (1725) (Cambridge, 2002) PDFGeorge IashviliNessuna valutazione finora

- The Idea of Being and Goodness in ST ThomasDocumento11 pagineThe Idea of Being and Goodness in ST ThomasMatthew-Mary S. OkerekeNessuna valutazione finora

- Ekphrasis and RepresentationDocumento21 pagineEkphrasis and Representationhugo.costacccNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis, John M. Tutuska, Aristotle's Ethical Imprecision. Philosophic Method in The Nicomachean Ethics, University of Dallas 2007.Documento242 pagineThesis, John M. Tutuska, Aristotle's Ethical Imprecision. Philosophic Method in The Nicomachean Ethics, University of Dallas 2007.vpglamNessuna valutazione finora

- Bibliographical Bulletin For Byzantine Philosophy 2010 2012Documento37 pagineBibliographical Bulletin For Byzantine Philosophy 2010 2012kyomarikoNessuna valutazione finora

- Marjorie Nicolson. The Telescope and ImaginationDocumento29 pagineMarjorie Nicolson. The Telescope and ImaginationluciananmartinezNessuna valutazione finora

- Aesthetic Ineffability - S. Jonas (2016)Documento12 pagineAesthetic Ineffability - S. Jonas (2016)vladvaideanNessuna valutazione finora

- Reduced - The Reformation and The Disenchantment of The World ReassessedDocumento33 pagineReduced - The Reformation and The Disenchantment of The World Reassessedapi-307813333Nessuna valutazione finora

- Halper Klein On AristotleDocumento12 pagineHalper Klein On AristotleAlexandra DaleNessuna valutazione finora

- Elena Kagan's Senior Thesis On Socialism in New YorkDocumento134 pagineElena Kagan's Senior Thesis On Socialism in New YorkHouston ChronicleNessuna valutazione finora

- White, Richard. 2005. Herder. On The Ethics of NationalismDocumento16 pagineWhite, Richard. 2005. Herder. On The Ethics of NationalismMihai RusuNessuna valutazione finora

- Composition of Photius' BibliothecaDocumento5 pagineComposition of Photius' BibliothecaDavo Lo Schiavo100% (1)

- THREE LOVES: GREEK, JEWISH, CHRISTIAN TRADITIONSDocumento3 pagineTHREE LOVES: GREEK, JEWISH, CHRISTIAN TRADITIONSDiego Ignacio Rosales MeanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Augustine's Confessions and the Search for the SelfDocumento4 pagineAugustine's Confessions and the Search for the SelfDiego Ignacio Rosales MeanaNessuna valutazione finora

- OpenInsight V9N16Documento326 pagineOpenInsight V9N16Diego Ignacio Rosales MeanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Szalay, Matyas - Edith Stein, Patron of Europe. Meditation On Philosophy As Testimony OIV5N7Documento27 pagineSzalay, Matyas - Edith Stein, Patron of Europe. Meditation On Philosophy As Testimony OIV5N7Diego Ignacio Rosales MeanaNessuna valutazione finora

- What Does It Mean To Be Civilized - Between Tradition and UtopiaDocumento4 pagineWhat Does It Mean To Be Civilized - Between Tradition and UtopiaDiego Ignacio Rosales MeanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chretien, Jean Louis - The Ark of SpeechDocumento178 pagineChretien, Jean Louis - The Ark of SpeechDiego Ignacio Rosales Meana100% (1)

- AA. Lampe Authors & WorksDocumento35 pagineAA. Lampe Authors & WorksDiego Ignacio Rosales MeanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ales Bello - The Study of The Soul Between Psychology and Phenomenology at Edith SteinDocumento19 pagineAles Bello - The Study of The Soul Between Psychology and Phenomenology at Edith SteinDiego Ignacio Rosales MeanaNessuna valutazione finora

- 18 Husserl - Letter To Alexander PfanderDocumento6 pagine18 Husserl - Letter To Alexander PfanderAleksandra VeljkovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Husserl (The Amsterdam Lectures)Documento27 pagineHusserl (The Amsterdam Lectures)Diego Ignacio Rosales MeanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Agamben, Giorgio - NuditiesDocumento76 pagineAgamben, Giorgio - NuditiesDiego Ignacio Rosales Meana80% (5)

- Logical Unit Number (LUN)Documento1 paginaLogical Unit Number (LUN)Shishir YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- Going to PlanDocumento5 pagineGoing to PlanBeba BbisNessuna valutazione finora

- Affective AssessmentDocumento2 pagineAffective AssessmentCamilla Panghulan100% (2)

- Standard Form Categorical Propositions - Quantity, Quality, and DistributionDocumento8 pagineStandard Form Categorical Propositions - Quantity, Quality, and DistributionMelese AbabayNessuna valutazione finora

- Western Philosophy - PPT Mar 7Documento69 pagineWestern Philosophy - PPT Mar 7Hazel Joy UgatesNessuna valutazione finora

- Plural and Singular Rules of NounsDocumento6 paginePlural and Singular Rules of NounsDatu rox AbdulNessuna valutazione finora

- Eli K-1 Lesson 1Documento6 pagineEli K-1 Lesson 1ENessuna valutazione finora

- Grossberg, Lawrence - Strategies of Marxist Cultural Interpretation - 1997Documento40 pagineGrossberg, Lawrence - Strategies of Marxist Cultural Interpretation - 1997jessenigNessuna valutazione finora

- PriceDocumento152 paginePriceRaimundo TinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Online Principal Transfer List 2021Documento2 pagineOnline Principal Transfer List 2021PriyeshNessuna valutazione finora

- Parang Foundation College Inc.: Course No. Descriptive Title Degree Program/ Year Level InstructressDocumento4 pagineParang Foundation College Inc.: Course No. Descriptive Title Degree Program/ Year Level InstructressShainah Melicano SanchezNessuna valutazione finora

- H. P. Lovecraft: Trends in ScholarshipDocumento18 pagineH. P. Lovecraft: Trends in ScholarshipfernandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Parasmai Atmane PadaniDocumento5 pagineParasmai Atmane PadaniNagaraj VenkatNessuna valutazione finora

- NumericalMethods UofVDocumento182 pagineNumericalMethods UofVsaladsamurai100% (1)

- Expository WritingDocumento9 pagineExpository WritingLany Bala100% (2)

- Q1 What Is New in 9.0 Ibm NotesDocumento17 pagineQ1 What Is New in 9.0 Ibm NotesPrerna SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- آسان قرآنی عربی کورسDocumento152 pagineآسان قرآنی عربی کورسHira AzharNessuna valutazione finora

- Authorization framework overviewDocumento10 pagineAuthorization framework overviewNagendran RajendranNessuna valutazione finora

- M18 - Communication À Des Fins Professionnelles en Anglais - HT-TSGHDocumento89 pagineM18 - Communication À Des Fins Professionnelles en Anglais - HT-TSGHIbrahim Ibrahim RabbajNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding How to Interpret Visual TextsDocumento23 pagineUnderstanding How to Interpret Visual TextsSeleena MaidinNessuna valutazione finora

- Checklist of MOVs for Proficient TeachersDocumento8 pagineChecklist of MOVs for Proficient TeachersEvelyn Esperanza AcaylarNessuna valutazione finora

- 103778-San Ignacio Elementary School: Department of Education Region 02 (Cagayan Valley)Documento1 pagina103778-San Ignacio Elementary School: Department of Education Region 02 (Cagayan Valley)efraem reyesNessuna valutazione finora

- SV Datatype Lab ExerciseDocumento3 pagineSV Datatype Lab Exerciseabhishek singhNessuna valutazione finora

- LISTENING COMPREHENSION TEST TYPESDocumento15 pagineLISTENING COMPREHENSION TEST TYPESMuhammad AldinNessuna valutazione finora

- Vocabulary for Weather and Natural PhenomenaDocumento4 pagineVocabulary for Weather and Natural PhenomenaSempredijousNessuna valutazione finora

- Michael Huth, Mark Ryan: Logic in Computer Science: Modelling and Reasoning About Systems, Cambridge University PressDocumento82 pagineMichael Huth, Mark Ryan: Logic in Computer Science: Modelling and Reasoning About Systems, Cambridge University PressHardikNessuna valutazione finora

- FCE G&VDocumento40 pagineFCE G&VMCABRERIZ8Nessuna valutazione finora

- CholanDocumento2 pagineCholanThevalozheny RamaluNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To SymfonyDocumento4 pagineIntroduction To SymfonyAymen AdlineNessuna valutazione finora

- 320 Sir Orfeo PaperDocumento9 pagine320 Sir Orfeo Paperapi-248997586Nessuna valutazione finora

- Out of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyDa EverandOut of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (10)

- Out of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyDa EverandOut of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (5)

- Just Do Something: A Liberating Approach to Finding God's WillDa EverandJust Do Something: A Liberating Approach to Finding God's WillValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (95)

- Now and Not Yet: Pressing in When You’re Waiting, Wanting, and Restless for MoreDa EverandNow and Not Yet: Pressing in When You’re Waiting, Wanting, and Restless for MoreValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (4)

- Tired of Being Tired: Receive God's Realistic Rest for Your Soul-Deep ExhaustionDa EverandTired of Being Tired: Receive God's Realistic Rest for Your Soul-Deep ExhaustionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Crazy Love, Revised and Updated: Overwhelmed by a Relentless GodDa EverandCrazy Love, Revised and Updated: Overwhelmed by a Relentless GodValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (1000)

- Bait of Satan: Living Free from the Deadly Trap of OffenseDa EverandBait of Satan: Living Free from the Deadly Trap of OffenseValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (307)

- The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness: The Path to True Christian JoyDa EverandThe Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness: The Path to True Christian JoyValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (188)

- The Dangers of a Shallow Faith: Awakening From Spiritual LethargyDa EverandThe Dangers of a Shallow Faith: Awakening From Spiritual LethargyValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (134)

- Jesus and the Powers: Christian Political Witness in an Age of Totalitarian Terror and Dysfunctional DemocraciesDa EverandJesus and the Powers: Christian Political Witness in an Age of Totalitarian Terror and Dysfunctional DemocraciesValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (4)

- How to Walk into a Room: The Art of Knowing When to Stay and When to Walk AwayDa EverandHow to Walk into a Room: The Art of Knowing When to Stay and When to Walk AwayValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (4)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsDa EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNessuna valutazione finora

- For Women Only, Revised and Updated Edition: What You Need to Know About the Inner Lives of MenDa EverandFor Women Only, Revised and Updated Edition: What You Need to Know About the Inner Lives of MenValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (267)

- Holy Hygge: Creating a Place for People to Gather and the Gospel to GrowDa EverandHoly Hygge: Creating a Place for People to Gather and the Gospel to GrowValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (100)

- The Deconstruction of Christianity: What It Is, Why It’s Destructive, and How to RespondDa EverandThe Deconstruction of Christianity: What It Is, Why It’s Destructive, and How to RespondValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (26)

- Strange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingDa EverandStrange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- The Blood of the Lamb: The Conquering WeaponDa EverandThe Blood of the Lamb: The Conquering WeaponValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (234)

- The Well-Watered Woman: Rooted in Truth, Growing in Grace, Flourishing in FaithDa EverandThe Well-Watered Woman: Rooted in Truth, Growing in Grace, Flourishing in FaithValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (63)

- The False White Gospel: Rejecting Christian Nationalism, Reclaiming True Faith, and Refounding DemocracyDa EverandThe False White Gospel: Rejecting Christian Nationalism, Reclaiming True Faith, and Refounding DemocracyValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (2)