Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Kruk Warrior Women PDF

Caricato da

Hana TuhamiTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Kruk Warrior Women PDF

Caricato da

Hana TuhamiCopyright:

Formati disponibili

WARRIOR QANNSA

IN ARABIC POPULAR ROMANCE: WOMEN AND OTHER VALIANT BINT MUZHIM LADIES PART ONE

about medieval Arabic popular fiction one One of the misconceptions is that the role of women in popular Arabic comes across occasionally to either that of the coquettish, is almost confined exclusively storytelling sensuous, often wily and amoral young beauty, or that of the vile old hag bent on destruction. Although scholarly research has long since amended this picture we still find such views lingering on. For many people Arabic popular fiction still means the Arabian Nights; but even these bear ample testimony to the contrary, as for instance Walther (1982) has pointed out. of a different character Among the various types of female protagonists in Arabic popular fiction there is one in parthat may be encountered ticular that deserves attention, she especially since, on closer inspection, turns out to be one of the stock characters of Arabic popular literature. This is the gallant female warrior, who turns up in a number of different forms. My aim here is to see how this widespread theme of folklore the in order to find world over is dealt with in traditional Arabic storytelling, How did the out exactly in what form it appealed to an Arab audience. in have this theme to be of to order sure present storyteller getting good storytellers ratings? For as to this, the practical outlook of professional will not have differed much from that of the makers of modern television and elements which did not appeal to the taste of the public programmes, are not likely to have survived for long. To this end, I have browsed through the Arabian Nights as well as the sira literature, without any intenthrough Arabic popular romance, tion of compiling a complete inventory of the stories in which such warrior women occur: Heath's (1984) rough estimate of the number of pages involved in such an operation comes to thirty thousand for sira literature alone, and a survey of this material is as yet beyond me. We are still eagerly waiting for somebody to chart out this material by providing us with surveys of the contents of the romances and related literature,' as well as presenting us with with indices of themes and motifs, as Elisseeff 1 Vol. VIII of Ahlwardt's Verzeichniss derarabischen offers valuable material Handschriften in this respect; Paret has excerpted Sayf ibn Dh Yazan (1924), the maghz literature (1930), and Umaran-Nu mn(1927) and surveys of Dht al-Himma are given by Nabila Ibrhm (n.d., pp. 34-57) and Canard (EI, s.v. Dh 1-Himma).

214 (1949) has done for the Arabian Nights, and, on a minor scale, Oliverius (1971) for Zir Salim. In this article I will make a first attempt at a typology of the "warrior as well as of the themes and woman" in Arabic (and related) literature, women" such women as motifs connected with her. I define as "warrior are trained in the chivalrous arts of fighting and combat. Thus a cirfierceness cumstantial handling of weapons, or even the unpremeditated V: 624 ff.) and fighting abilities of Maryam the Girdle-maker (Littmann however do not suffice to make a woman qualify as a "warrior woman", destructive her actions against her enemies may be. I have avoided the word "Amazon" because it is encumbered by a vast amount of connotations so far removed from the stories here discussed (see Blok 1991) that it becomes virtually useless for the present purpose, and a more neutral term is to be preferred. of the type mentioned First, the Arabian Nights. Female protagonists above do figure in several of its stories. Most prominent among them are Abeiza and Shawahi in the romance of King ?Umar an-Nu'mAn (Littmann 1: 550- II: 224), a piece of sira (or geste) literature incorporated in the Arabian Nights); the theme further comes up in two of the stories belonging to the cycle of the Seven Vizirs, namely "The man who never IV, 303-312); in "Prince Bahram laughed again in his life" (Littmann and Princess ad-Datma" IV, 334-40); and in the story of (Littmann Basra of Hasan V, 315-503). (Littmann The story of 'Umar an-Nu'min, a geste-type of story that has much in common with the vast Sirat al-amira Dhat al-Himma to be discussed below 2 (see Canard 1937), offers us the charming figure of Princess Abriza.2 One night when Prince SharkAn, one of the leading heroes of the story, rides out alone in the moonlight, he unexpectedly comes upon an scene (I: 510). Near the walls of a Christian a enchanting monastery group of beautiful young girls are sporting in the meadow. Their leader subsequently challenges them all to wrestle with her and defeats every one of them. Then a jealous old woman (depicted in a very crude way) challenges the girl and also demands to fight her; the girl does so with reluctance, defeating the old woman (called Dhat ad-Dawahi, Calamity Jane) without much effort. Prince SharkAn, enthralled by the spectacle, comes into the open and is also invited to fight the girl in unarmed combat. Although he equals her in adroitness and is superior in strength, he loses, confused as he is by the touch of her body. When she allows him a second chance the same thing happens, and the third time it is a sudden 2 On Abrza's literary affiliations with the Persian Smnme see H. Wangelin, Baybars (B.O.S. 17) p. 205 note 109, referring to ZDMG 3, 1894, 254 ff.

215 exchange of smiles that enables her to catch him unawares and throw him In a chivalrous to the ground. gesture the Christian princess, whose name is Abriza, then offers the stranger hospitality. During one of the is offered to the guest she ensuing nightly sessions when amusement him time in a chess game-again to defeat a fourth this time, manages because a look at her beautiful face causes him to make a wrong move. The same thing happens in every one of the four games that she offers him in return. Here the story touches upon a variation of the girl-defeatsman theme not involving physical violence, a variation that also crops up in the story of Tawaddud, where the in other stories, most prominently is to the "learned woman" motif.3 3 male/female contest theme joined The sudden arrival of Abriza's co-religionists causes the breakup of the party and SharkAn has to flee, after having gained Abriza's promise to leave the Christian camp and to come to him after having obtained for him certain valuable jewels which his father covets. In the sequence of the story Prince SharkAn at a certain moment has to face an army of Christian warriors who manage to capture his companions; he himself is engaged in combat by their leader. The fight goes on for days, while he is unable to defeat his opponent, until this one finally throws himself on SharkAn's upon mercy purpose: and behold, it is again Abeiza, who her superiority in battle before joining him. on to him was bent proving She has managed to bring him the promised jewels, and happily joined in their mutual love (which remains chaste) they depart for the court of SharkAn's where Abeiza is received with due father, King ?Umar, to Islam (explicitly stated later in the story, honour. She is converted there can no talk of marriage Littmann II: 200). Strangely, between SharkAn and Abriza, even though he confesses to her that his father's obvious attraction to her worries him. She promises to kill herself, if the king should take her by force. Sharkan's anxiety turns out to be wellfounded : the king's passion for his beautiful guest (who refuses his offer of marriage) leads him to drug her with banj in order to fulfil his desire. When Abriza comes to, she finds herself violated, bleeding, and, as it turns out, pregnant. With her maidenhood she also appears to have lost her gallant courage. When her pregnancy can no longer be concealed she and a furtively leaves the palace, accompanied by a female attendant black slave whom she mistakenly trusts. The slave turns out to be lecherous to the extent that he makes amorous advances to her at the moment of parturition. When she indignantly refuses he kills her in 3 For examples of the latter, see Elisseff, Thmes et motifs,under "Femmes savantes"; among them is the episode of Princess Nuzhat az-Zamn's examination included in the story of 'Umar an Nu mAn (Littmann I: 599 ff.).

216 anger, and it is from the princess' dead body that the female attendant elsehas to draw forth her baby son. This latter motif is also encountered where : in the Sirat Dhat al-Himma the birth of the hero al-Junduba, the takes place under similar cirof DhAt al-Himma, great-grandfather cumstances. So much for Abeiza; but the old woman, Shawahi Dhat ad-Dawahi, is not so easily defeated. This indomitable lady, who is the mother of the Abriza's Christian king Hardub, father, goes on counseling her son, and when he is killed by the Muslims she stops short of nothing to avenge his death. She climbs walls, commands kings and armies, disguises herself as a hermit in order to trap the enemy-she is the real power behind the to the camp of the "baddies" throne of the Christian kings. Belonging a wealth of disgusting characteristics. in the story, she is adorned with Only by a despicable ruse do her enemies succeed in defeating her, and she occaat the end of the story she is cruelly put to death. Although the to off a sword she does not brandishes head, chop sionally regularly engage in armed combat herself, and thus cannot be classified as a "warrior women" within the definition given above. in the story There is another short reference to a "warrior woman" of 'Umar in the an-NucmAn, II, 180 ff.) namely episode (Littmann where Prince Kin-mA-kAn for his beloved is taken by his opponent who has vowed that she will marry no-one but the man who Khatun, defeats her in combat (this episode has an almost exact counterpart in the one mentioned below from the Sirat Dh4t al-Himma). In "The man who never laughed again" a young man opens a forbidden door and miraculously arrives on an island where he is met by a large of headed women, army by a queen. As it turns out, this is an island where the normal order of society is reversed: all the handiwork is done officials are all women. by men, whereas the soldiers and the government The virgin queen asks for the young man's hand, and they are married by a female q4di, with female witnesses. Their happy life comes to an end when the young man opens, again, a forbidden door. Bahram" In "Prince the prince endeavours to win the hand of a princess who will only consent to marry a man who defeats her in combat. She is a skilled warrior, but of course the prince accepts the When he starts to gain the upper hand she manages to confuse challenge. him by opening her visor: dazzled by her beauty, he forgets to concentrate and is quickly thrown out of the saddle. He is robbed of his mount and armour, and she further humiliates him by branding his brow with the words: "This is ad-Datma's client". His ardour, is however, and he in to her into unabated, finally manages, disguise, trap marriage by making use of her interest in jewels and fine clothes. He takes her

217 virginity by force, thus breaking her resistance against marriage; and she concludes that she has no choice but to leave her country and follow her husband. Hasan of Basra, in the story of that name, has to recover his wife and children from the islands of Waq, where her father is king. The army on thousand these islands consists of twenty-five women, and the eldest sister of Hasan's wife, who is appointed governor by her father, commands them. Hasan throws himself upon the mercy of one of the women The woman in question turns out to be soldiers and begs for protection. an old lady, named Shawahi or Dhat (sometimes Umm) ad-Dawahi (cf. Her physical appearance the story of cumar is, just as in crude and described in an extremely the story of cumar an-NucmAn, Shawahi she becomes one of the but unlike the other manner, disgusting and if of is to the of the she self-sacrifice, "goodies" story: helpful point it had not been for her, Hasan and his family would never have escaped. In this story, few details about the women soldiers are given: we are told that they can fight with sword and lance, and that when they mount their horses in full armour, each of them equals a thousand knights (p. 347). Their commander, the princess, upon hearing of her sister's marriage, deals with her in a very fierce and cruel way, but shows tenderness towards her two small nephews. still to a large extent Other Arabic folktales as well as sira literature, of this of form a rich source stories type. Sabine Schwab unexplored, in this kind of a number of instances has summed up (1965: 52-55) literature as well as in shorter Bedouin tales, all of them examples of what she terms the "Brunhilde-motif", i.e. the woman who consents to marry 4 only the man who defeats her in combat.4 4 The cases which she points out are: Miqdd and Mayysa (one of the three stories dealt with in her dissertation; here, too, emphasis on the conquering effect of the heroine's beauty); the maghz story of the raid against Zibriqn b. Badr (Paret 1930: 144); Sayf and Shma from the Sirat Dh Yazan, discussed in the article, and in addition to that the story of Dht al-Wishhayn that is related to this Sra (Ahlwardt Verzeichniss Ar.Hss. Vol. VIII, no. 9221); from the Sirat Antar: Hind, who fights Qays ibn Mas d, ed. Cairo 1366, 8 vols., and is herself defeated by Rab ab. Muqaddam (Sirat Antara, VI: 62 ff.); Queen Tala a,who after three-days' combat is defeated by the Indian King (VI, no page ref.); Ghamra and Hayf, who both fight and marry 'Antar (VIII: 273 the sister of the Tubb (Ahlwardt op. cit. VIII, 155 ff.); from the Sirat Ban Hill: Su d, ff.; to this ref. add Oliverius 1971: 141); in Turkish literature: ref. to H. Eth, Die Fahrten des SayyidBattl II: 78, also the " Brunhilde motif", and finally a Persian epic with a female main hero, the Gushasp-nme,discussed Heller 1931: 80. To these ref. can be added those of Paret; (1930: 136, Ghamra's with Talha, and 144, Thurayy, who kills three hundred suitors. For the occurrence of the male-female contest motif in folk literature in general see Thompson 1932-6 under: T58- Wooing the strong and beautiful bride; H 345- Suitor test: overcoming princes in strength; H 332.1 -Suitor in contest with literature Lichtenstdter (1935: 79) gives only one bride. From the Ayym al- Arab instance of a woman talking up arms to participate in fighting; killing off the wounded enemies was a task more commonly left to women (id. 42).

218 One of the three stories which form the subject of her book (KhansZ> and Sakhr) presents a type of "warrior woman" occasionally met with in Arabic literature, namely the woman who has not had a professional training in the art of warfare but who is driven to it by her urge to avenge the death of a beloved person. Such is the case with KhansA' in the story of that name. Schwab (18-20) points out a few similar instances, in the Sirat Bani Hilal. especially I will mention a few more examples from Sira literature. In the Sirat Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan (for a survey of its contents, see Paret 1924), the role of women as active protagonists in the story is quite prominent. Time and again, the hero is saved by women from the dangers that he has brought upon himself; active in this respect are especially his fiancee, Shama, and his jinn foster-sister 'Aqisa. A warrior woman with distinctly in this story is the hero's mother, Qumriya. She negative characteristics puts her baby son out into the desert (I, 24) because she dislikes the idea of having to retreat from power once he is grown up. When, later on, they are on opposite sides in a war without realizing their relationship, Qumriya attempts to avoid battle by coming to his tent at night and suggesting to decide the matter by joint combat (II, 49-50; Pa. 12). When he agrees, she suggests to him that they both strip before battle, convinced that her naked body will confuse him to the extent of ensuring her an easy victory. When he undresses, however, she recognizes around his neck the necklace that she put there when he was a child. She discloses their relationship, but immediately devizes a plot to kill him; when she finds out that this has failed, she continues her attempts, while again and that she has repented, until she again her son lets himself be persuaded is finally killed by Tamma, one of Sayf's prospective brides. His fiancee ShAma is a gallant warrior, who tests his valour by luring him into combat disguised as a male warrior (I: 43-44). Only with the utmost difficulty does he succeed in defeating her. She repeatedly comes to his assistance in hazardous situations, and joins him in battle (I: 49). She marries him, but her mother-in-law Qumriya has her carried off by sorcery during her She wedding (I: 32); not, however, before Sayf has made her pregnant. bears him a son (III: 40), and is rescued in due course. Sayf meets a veritable Amazon queen during an episode which is practically identical to that described above in the story of Hasan of Basra in the Arabian Nights (V: 60 ff. ). He, too, has to recover his wife, Munyat from the isles of (here) Waq al-WAq, where he cuts a poor an-Nufus, figure when, disguised as a woman, he visits the women's island (there is another island inhabited exclusively by men) and joins the girls in their ball and combat games. The helpful role is here played by the old vizir MarjAna, and by Kawkab, the girl who acts as prison warden. Kawkab

219 takes pity on Munyat an-Nufus, who is badly beaten by her sister Queen Nur al-Huda, and unbinds her fetters so that she can nurse her baby son who is with her in prison (V: 61). Sayf comes to the rescue and defeats an army of girls (VI: 6) and a discussion takes place about the best way to remedy the unnatural situation of segregation of the sexes; this is finally brought about by sorcery (VI: 8-9). Queen Nur al-HudA is given in marriage to one of Sayf's companions. Sayf also meets with two warrior queens, the beautiful and sweetwho is not yet thirty years old, and her cousin tempered Red Thurayyi, the vile and loathsome Blue ThurayyA, who is a hundred and fifty years old (IX: 14 ff.). They both rule over a city and are rivals; both have learnt to practice sorcery and soothsaying. armies of They command men. The Red ThurayyA, who is a Muslim (IX: 15) falls in love with Sayf and invites him to marry her (IX: 17); she concludes from his vague answer that the matter is decided, and that "he would be her husband and under her command" (annahu sara baclaha wa-taht amrihg wa-nahyiha); before a marriage can take place, however, the Blue ThurayyA captures war do his companions sucSayf, and only after a long and complicated ceed in rescuing him. The Blue Thurayyi is very difficult to defeat: a long combat between her and the hakima ?Aqila (the mother of the reckless girl Tamma who also plays a prominent part in the Sira, and marries Sayf) remains undecided 3 The story ends with the (XI: ff.) death of the Blue ThurayyA, who refuses to convert to Islam (XI 15-16), and the marriage of the Red ThurayyA to one of Sayf's s companions (XI: 17). The Sirat al-amira Dht al-Himma (some five thousand pages in the Cairo edition of 1909, which consists of seven volumes, and which divides the story into seventy parts; references are to this edition) is of course the example par excellence of an Arabic story featuring a warrior hero being a warrior princess. On the different woman, its eponymous versions of her name-Dhu see 1-Himma, Dhat al-Himma, Dalhama-, Canard's article "Dhu 1-Himma" in the Encyclopaedia of Islam. Dhat al-Himma, is a fearsome warrior, the originally called Fitima, female descendant of a long line of remarkable Bedouin heroes. Indeed, the fact that she turned out to be a girl was such a disappointment to her father Mazium that he considered when he was held her, and, killing back by his womenfolk from this vile deed, he refused even to look at her: la yashtahi an yargha li-anna l-bint makrha cind ar-rydl "he did not want to see her because men detest girls" (I, part 6 p. 15). (Later, however, the with her father, 7: 10 f. and 7: 31). As girl will have a close relationship a result of her father's attitude the little FAtima is brought up by a foster mother away from her family. During a raid they are captured by hostile

220 but even at the age of five (when she is already so well that she looks ten) she is too proud to accept slavery, physically developed and threatens to kill herself, thus proving her noble descent. Brought up in the household of the Banu Tayy chief who has captured her, she a taste for and horse-riding develops very early fighting, going out in the field and practising with lances made of reed-stems. When, out in the accosted by a man who disdains to accept her field, she is repeatedly offer to take her as his wife, she kills him with his own sword guardian's Thus (6: 20). begins her career as a warrior feared among the tribes. She is averse to marriage, although her cousin al-Harith considers her as his lawful spouse: hiya bint camm wa-hal4li, "she is the daughter of my father's brother and thus by law permitted to me" (7: 8-9). Frustrated follows the by her refusal to have marital relations with him, al-Harith advice of cuqba, the treacherous with the of her fosterqa,di, and, help brother Marzuq , drugs her with banj in order to be able to fulfil his desire (7: 10). As a result Fitima becomes pregnant and bears a son, cabd alturns out to be black (7: WahhAb, who, to everybody's consternation, The im4m is consulted and 11). jacfar a?-Sdiq explains (7: 39) that this is because he was conceived at a certain time during menstruation, thus father shame on the instead of on the mother. cabd al-Wahhlb casting grows into an valiant warrior, who battles side-by-side with his mother. illustrated in the She, however, keeps the superior role, as is beautifully vivid picture (II, 20: 24) of Dhat al-Himma striding along the ranks cursher with because of his son, crying ing rage unworthy behaviour towards his friend al-Battal in the case of Princess Nura, with cabd al-Wahhib keeping out of sight, knowing that his mother will very likely kill him should he dare to show his face. But Dhat al-Himma, redoubtable warrior as well as devoted mother, who is leading character of the story, feared and respected by all, even her enemies, is by no means the only female warrior who figures in the epic. It is, in fact, crowded with stories featuring female heroines, a fact that only adds to the intriguing question of this epic's origin and growth. I will briefly discuss here some of the stories and add a full translation of one of them, the story of the princess Qannasa. It is one of the few stories that are easily translatable in this form, because the course of events is not constantly with other episodes. interspersed Lane, in the admirable chapters on Popular Romance included in his Manners and Customs, briefly sketches the contents of the adventures of Dhat 1-Himma's warrior women. with great-grandfather al-Junduba One of them involved a fearsome lady called ash-Shamti' ("the Grizzle", translates Lane), who leads an army of men (I, 1: 14) and manages to capture al Junduba's and brothers. He manages to defeat foster-father Bedouins;

221 her followers that it is a shame for them to obey ash-ShamtA), persuading an old woman. Of ash-ShamtA)'s particulars nothing further is told than with lance and sword, and that she a fierce and that she is capable fighter is an old woman (Cajz). In a later adventure al Junduba engages in a fight with a beautiful lone 1825: 68warrior 1: the 23; story was included in Kosegarten (I, young the when at to throw to the whom he point of strikground; manages 83), voice for a female he hears soft mercy. It is the beg ing the final blow, of the Valiant". She takes him to princess Qattlat ash-Shuj?an, "Killer Her men, however, her people and receives him with great hospitality. threaten to kill him. She persuades them to wait till morning and during conafter they have, at her suggestion, the night flees with al-Junduba, Innahumd as their witness. with God cluded a marriage tasdfa4d waonly tankab, "they shook hands and became man and wife", the story says brings her to his people, in the course of which event (1: 27). Al Junduba comshe valiantly assists him in battle. She remains his inseparable of the son one even on until day HishAm, hunting expeditions, panion, not rest till he her and does the caliph ?Abd al-Malik, falls in love with is stricken with grief, but is consoled by has abducted her. AI-Junduba a new marriage (1: 40); Qattlat ash-ShujcAn, on the other hand, conand as he starts to sistently refuses to give in to her captor's demands, on his political failure have about the effect which this may worry in secret (1: 40). prestige, he has her killed and buried woman" theme (in the form of the "Brunhilde The "warrior motif ') of is also briefly brought up in an episode (2: 3) where the companions him to son the as-Sahsah, al-Ghitrif, persuade go enemy ofal-Junduba's and fight a beautiful female warrior called Zaynab, whose beauty and valour have attracted many suitors and who has promised to marry the is that al-Ghiteif is such man who defeats her in battle. Their argument a paragon of masculine beauty that Zaynab (whose ultimate purpose in life, they say, must needs be to capture a man, as with all women) will easily let herself be defeated. Al-Ghitrif indeed goes out and meets an unknown warrior whom he supposes to be Zaynab, but who turns out above in to be as-Sahsah. This episode is very similar to that mentioned the story of ?Umar an-Nu?man. of the story of Abeiza has parallels in several other The beginning them the story of Aluf in the Sirat Dhat al-Himma (3: stories, among 78 ff.). Large parts of the two stories are literally identical, but the way different. in which the Dhat al-Himma version develops is significantly Here it is as-Sahsah who on a moonlit night comes upon a castle (in the where he witnesses the spectacle of a other version, it was a monastery) Princess beautiful young woman, Aluf, wrestling with her companions.

222 He, too, is invited to wrestle with her, and loses three times, confused as he is by her beauty and the intimate contact with her body (this latter elaborated upon in this version). Aluf aspect is rather enthusiastically to marry: wa-an Id arghabu fi z-zawdj wa-l f professes her unwillingness do neither long for marriage nor r-rijl bal yamilu qalbi ild rabbt al-b'l, "I for men, but my heart has an inclination for the ladies" (4: 6); she is, in too books and practising the chivalrous moreover, engrossed reading arts to bother with marriage. she is not interested in showNevertheless, of the Muslims, although ing off her courage by attacking the vanguard she could easily do so. As-Sahsah spends a pleasant (but chaste) time with her, and upon rejoining his fellow Muslims he tells Prince Maslama an-NucmAn version about the girl (here the parallel with the cumar in his Maslama falls love with the passionately ends). Upon description, makes him the castle. The with and to ends as-Sahsah guide girl story the conversion of all the castle's inhabitants to Islam and the marriage of Aluf and Maslama (4: 37). After her marriage Aluf continues to play an active part: she joins the Muslims in their war against the Christians, which offers her ample opportunity to practice her "God-given" (4: 27) out her husband and his soldiers, someShe rides with fursya, chivalry. times leaving them behind in her fighting ardour (for instance 4: 46, 5: 3). She does not hesitate to set the occasional head flying (4: 76-77), and takes part in the discussions that go on among the men (for instance 4: 64. 65). ' 59, Christian Apart from the non-combatant girl TamgLthil who, for reasons of personal safety, travels in male disguise (4: 57, 58), and the jinniya with whom as-Sahsah becomes involved (5: 57) there is another remarkable lady who crosses the path of the Muslims in the course of unattractive their siege of Byzantium. This time it is an extremely 1969: Georgian queen by the name of Bakhtus (see Canard 16-19), to whom the Byzantine emperor Lawun appeals for help (5: 8). She is an old and ugly but fearsome lady, reported to be a hundred and sixty-three years old (5: 13). She is endowed with redoubtable fighting abilities as and if her luckless male well as with an insatiable sexual voraciousness, partner cannot keep up with her she is wont to cut off his head and to crush it under her ampit until the eyes pop out (5: 13). Her sexual appetite, however, leads to her doom when she devotes her attention to a young Muslim, MidlAj, whom she has caught with his pants down in battle (5: 16), a sight that greatly impresses her. His staying power is such that he succeeds in quenching her desire, and, when, inattentively, she dozes off to sleep he pierces her with his sword (5: 17). The first part of the story of Abriza also has a parallel in the way in which Princess Nura makes her appearance in the Sira. Nura is the

223 the King of the Blood Castle, one of seven daughter of 'Ayn al-Masih, Christian brothers who each govern a castle. Al-Battal discovers Nura in the garden of a convent (13: 47), where she makes merry in the company With the latter she has a of three monks and ten female companions. with in a is dealt match single line; it is obviously wrestling (this episode a well-known motif). Nura, "who loves women and detests men" (tahwa an-nis) wa-tubghidu r-riid discovers al-Banl behind the gate and invites to make merry with the him in, and subsequently also his companions, girls. Nura defeats all the men in wrestling; they claim to be defeated by her beauty rather than by her strength. This is the beginning of Nura's s which will lead to many rivalries with the Muslims, long involvement between the men who fall in love with her. Fighting begins, and Nura takes an active part (13: 78, 79). 'Abd al-Wahhib manages to strike her shows down with his sword, and she is taken captive. Dhat al-Himma When her. she is the men to untie brought compassion by ordering before 'Abd al-WahhAb and he looks at her, standing there in a purple with pearls (13: 80), he is irretrievably lost. He takes dress embroidered her away to his castle, to the great chagrin of al-Battal, who puts his case before the caliph Harun. The caliph, intrigued, goes to cabd al-Wahhib him of their life together. "II and asks about the (16: 46), arrangements live with her like a little bird with a small child" (hukm cayshat al-cuifr for he has not had maca j-jfl as-saghir), is the answer of cabd al-Wahhib, the heart to force Nura against her will. The caliph demands to see her, As Steinbach and is also greatly taken with her. (1972: 104) remarks, Nura resembles the Greek Helen in the fateful effect that she has on men. She does not, however, play a passive role. She is a redoubtable opponent in war, and is quite prepared to turn the men's weaknesses against them by making use of her physical attraction in combat : when the Muslim heroes go out one after the other to battle with a mysterious knight (II, 20: 17) from the enemy ranks, they are all defeated because as soon as they come within range the knight smiles seductively and pulls open her shirt to display her pomegranate breasts. Her story, which takes up a considerable part of the Sira (almost a whole volume), deserves a more extensive treatment than can be given here. Suffice it to that she marries becomes a Muslim, al-Battal, say finally goes on to Mecca and the Muslims in their campilgrimage joins (III, 21 : 6-7) the and Franks. paigns against Byzantines Zananir is another Christian princess (malika is the title usually given to these women) who crosses the path of the Muslims. Her story starts after that of Nura has come to a conclusion. Zan3Lnir's father is shortly the Christian She first makes her in 24: 24, king Salbuta. appearance where she is presented as living in a monastery with her sister Salbin and

224 her mother. The princess living in a monastery is a common motif: see for Shamsa Zananir is a very beautiful also, instance, princess (23: 35). 24: in has told her a dream that she should girl (description 74). Jesus only marry the man who defeats her in battle. The old king Sha)sha)fina is the first to try. However, he becomes very confused by the contact with her body and Zananir easily defeats him. He tries a second time, but how could ZanAn^ir, who, as the story says (24: 65) does not even feel desire towards young men, be interested in an old man? She shows off her the back of her horse without using the stirrup strength by jumping upon and hurling her lance far away into the field instead of aiming it at Sha)sha)Cin,i's breast. She declines to fight with him, and advises him to go and look for another bride (later on, he will be cured of his love for Zananir and marry her slave girl NahAr, 25: 33-34). Subsequently she defeats all her other suitors. Al-Battal, who with his servant Lullu' and other Muslims is a prisoner in the Christian camp, has been a spectator. He compliments her but considers her inferior to Dhat al-Himma. Zananir confesses her lack of interest in men: she is inclined towards the ladies (rabbt al-hydo (23: 67). She has a favorite slave girl, Nahar, with whom she amuses herself (zvatataladhdhadha, 24: 80) and is depicted as being extremely drunk together with her slave girls (15: 1). Lu'lu) falls in love with her, and is chided for this impertinence desperately by alBattal, but his master cannot but be moved by the deep sincerity of his theme in the sequel of feelings. Lu)lu)'s love for Zannr is a recurrent the story. Zananir's like that of Nura, has a devastating appearance, effect upon the men she meets (even the bad ql ?Uqba falls in love with her, 24: 73). Finally she consents to marry Lu'lu', persuaded by Dhat al-Himma (29: 50). She joins the Muslim band of warriors and continues to play a part in the story. We meet her, for instance, in 36: 23, where she goes out to battle, and in 55: 54ff., where she takes part in a frivolous scene involving ample musical entertainment. Another Christian princess is Karna (33: 37), who successively defeats a whole army of Muslim knights who have taken up her invitation to meet her in single combat. At last 'Abd al-WahhAb takes his turn. When he is about to gain the upper hand his horse stumbles in a jerboa's hole, and she captures him (33: 41). Finally it is again Dhat al-Himma (in admiradisguise) who defeats and captures her, duly gaining Karna's for 'Abd al-Wahhib tion ; Karna is subsequently exchanged (33: 45). a later she is back During episode among the Muslims (34: 51), and the caliph Ma)mCin as well as the warrior Ab6 1-Hazahiz aspire for her hand. to engage in battle, but is During this episode she gets no opportunity in a howdah. She becomes involved in a long and comtransported of the and is finally discovered plicated intrigue qddi 'Uqba, disappears,

225 in Byzantium, together with another Christian princess, Malika (35: 16). too, is a gallant Christian Maymana, princess who finally joins the Muslim army. She is the daughter of 'Abd al-WahhAb's enemy Damseven whom and has brothers with she used to daman, practise the art of combat (IV, 37: 50). When her father captures "Abd al-WahhAb and holds him captive (IV, 36: 39) she is excited by the idea of being so near to the famous hero. She has a flippant conversation with him (36: 51); she boasts of her chivalry, but he does not believe her; she falls in love with him (36: 52) and has a heated conversation with her father about the rightness of her infatuation She tries to come to terms with (36: 55). her changing feeling towards her father by trying to convince cabd alWahhAb of his chivalrous qualities (36: 56). In the end she kills her father (37: 9). During a battle cabd al-WahhAb disappears from her castle (37: 8). She is desperate and seeks him among the dead on the battlefield. Finally she meets him in battle (37: 10-11). She wins the combat, but he begs for mercy. She spares his life but is adamant about renewing their former good relations: "Even if I were to throw out my liver piece by if I were to drink piece, passion sip by sip and to cry over you till my tears ran out, there would be no question of renewing my ties with you". fail; she defeats az-ZAlim, Attempts to conclude peace with Maymana cabd al-WahhAb's succeeds in gaining vicson; finally Dhat al-Himma starts tory over her in a combat that takes two days (38: 38). Maymana to feel a deep sympathy for Dhat al-Himma, and asks to be married to 'Abd al-Wahhib; but no direct steps are taken. Maymana joins the Muslim army and henceforth fights side by side with Dhat al-Himma and her companions. Then there is Ghamra, the spirited Bedouin girl whose feelings of love for her cousin ?Amir are grievously hurt by her cousin's reaction to her tentative suggestion of marriage: he does not take an interest in women, since they can only keep him away from his far more important and chivalrous pastimes (IV, 40: 59). At first she is inconsolable, interesting but then she goes hunting, by her mother. She tracks her encouraged cousin and, disguised as a man, she defeats him in combat. Then she leaves her outfit with her nurse, who later on lends the clothes to camir. He recognizes them as the clothes of the warrior who defeated him, hears the truth, and falls deeply in love with his cousin, who, however, refuses him (V, 41: 16). She takes part in battle, but does not allow anybody to her with talk of marriage; hatred for her people, the Banu approach Kilab, finally drives her away to the south of Arabia, where she becomes a brigand in the region of Hadramawt (V, 41: 43). For the present, this much may suffice to illustrate the part of women in Arabic popular literature. That the theme of the warrior woman is by

226 rare in popular literature in general but is exceptionally wellin the Sirat Dht al-Himma is the list of ladies clear; represented figuring in the book given above is by no means complete. Dhat al-Himma could be termed, other things, a collection of "warrior virtually among woman" in the framework of the story of Dhat alstories, embedded Himma herself and to a certain extent following the same pattern. Little or no attention seems to have been paid so far to this aspect of the Sira; the existence of such an epic (or epics, for there is at least one other examthe Persian Gushasp-ndme mentioned literature, ple in Middle-Eastern by Heller (1931: 80)), as well as the fact that this type of story was widely appreciated by Arab audiences from (at the very latest) the eleventh to the twentieth For the century seems to have been taken for granted. of the see Dhfi 'l-Himma. sira, Canard, EI, dating To conclude, let me sum up some of the more frequent themes and motifs that figure in these stories. There are traces of the "warrior woman" theme familiar from the classical Amazon myth, in which we are confronted with an inverted order of society implying a change of role between male and female. Such elements can be found in the story of Hasan of Basra and its parallel in Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan: the women's society on the Isles of Wq (or Wq alIn The man who Waq), where the male element is virtually eliminated. never laughed again the "inverted world" theme is emphasized by his entering through a forbidden door. Traces of the Amazon theme can also be found in the women's army in the story of Abriza. The ambivalent attitude towards sexual relations which formed part of the classical Amazon myth can also be pointed out in some of the Arabic stories: the fury of the Waq al-Waq queen towards her married sister; the avowed lack of interest in men, and sometimes towards proclivity in of the Abriza's loss of women, expressed stories; many fighting power after she has been raped. It is interesting to see how the stories of Abriza and Dhat al-Himma seem to present an intermediate form between stories of the type in which the male element is rejected and considered as absolutely destructive for female power, and those in which being a warrior woman is in no way incompatible with being a wife and mother. The impression one gets is that the storytellers' urge to create warrior heroines who fitted in with the popular conception of what a successful woman (i.e., a woman who has respectably become the mother of a son) should be like, first came up with the device of the "unconscious" loss of virginity and resulting pregnancy; in Abriza, this still carried the sanction of loss of power and, eventually, life; the fact that the sexual act had taken place in an unlawful situation made this an almost inevitable outcome. In Dhat al-Himma a lawful solution for the dilemma is found, sancno means

227 tions in the form of loss of power or life are removed, and Dhat mother while still remaining al-Himma can become a respectable a relations redoubtable warrior, without, however, being encumbered by Dhat al-Himma with her ephemeral husband has (love is something In many of the other stories this "curious never experienced). conception" element has also disappeared, and we see warrior women who produce sons in ordinary (or, at least, undisputed) marriages while contitheir career. fighting nuing This also implies that the "warrior is a regularly occurring couple" theme: Sayf and ShAma; as-Sahsah and QattAlat ash-Shujcin; Maslama and Aluf. The stories frequently emphasize the femininity of the warrior woman. Several devices are used to this end: the motif of the woman who is at first taken for a man: this guarantees maximum effect when her The is disclosed. of the woman is frequently femininity beauty The woman may also consciously make use of her feminine emphasized. assets in battle, as Nura does by smiling and displaying her breasts, or by suggesting a nude wrestling match. The confusion of the Qumriya men upon their intimate contact with the woman's body is frequently with The men often elaborated upon great relish by the storytellers. excuse themselves for their defeat by saying that it is the woman's beauty that has defeated them rather than her strength. The description of sometimes the of birth motherhood, process giving including (Abriza, Dhat al-Himma, is another way of emphasizing the warrior Shima) woman's femininity. it is the woman herself who becomes the victim of a supSometimes feminine weakness: in Prince Bahram, it is by making use of her posed love of jewels that the prince, who has not been able to defeat Princess Datma, finally gets the better of her. Moral badness in warrior women is, according to a familiar pattern not restricted to this group, demonstrated by describing them as old, ugly and of insatiable sexual voracity (Bakhtus, Qannasa) The male-female contest motif has already been discussed. It occurs and may take either the form of an intellectual contest, very frequently, of a suitor's contest, or of the woman who wants to prove her superiority to a man by defeating him in combat (Shama, Abriza, Ghamra). Another motif is the single combat between two women, popular sometimes an old and a young one, which also symbolizes a bad-versuscan be pointed good fight (Abriza and Shawahi). Frequent occurrences out in Dh6t al-Himma. In many of these cases Dhat al-Himma fights (and a future thus the down defeats) daughter-in-law, laying pattern of their relations in future.

228 a castle) in which a group of women is The monastery (sometimes of these found to live together is a standard setting for the beginning female setting stories. It is usually in the context of this predominantly that a stock remark is made about the heroine's general lack of interest meant to in men, a circumstance obviously emphasize the success of the . hero who succeeds in overcoming her aversion. observation As will have become clear from the above, Steinbach's the warrior woman tends to that after her fade from marriage (1972: 103) with the of Dhat al-Himma is herself, public life, exception clearly inaccurate. Nor is it true that with her virginity the woman loses her fighting power (id. 103 note 5), at least not in the Dhat al-Himma stories. The married warrior woman continues to take part in fighting, and in addition to that it can be observed that war in this epic is very much a family affair. We call to mind the daughters of Hayyaj, mentioned above: they were seven sisters, and together with their father, their mother Ghayda) II, 11: 29, 30) and their cousin they took part (her name is mentioned in battle: "Those ten knights were HayyAj al-Kurdi, his wife, daughters and nephew" own wife, 'UlwA, goes to (I, 10: 37). 'Abd al-Wahhib's war in the company of their son Ibrahim (II, 15: 3), his wife Qannasa with their son ZAlim (see Part 2), al-Battal's wife Nura continues to participate in the campaigns (V 41: 21), and al-Battal also begets a valiant for instance VII, 69: 102). It is no different on the daughter (mentioned Shuma, and their son enemy side: the wife of the bad monk Shumadris, Dahrshum also take part in battle proceedings (for instance II, 20: 19). there will follow in Part 2 ( JAL XXV Part 1) a As an illustration, translation of the story of Qannasa, one of the "warrior woman" stories from the Sirat Dhat al-Himma (vol. II, part 11: 12) in which many of the elements listed above appear. For those interested in the sequel of the story: Qann:;;a's career as a warrior woman does not end with marriage. When the story continues and ?Abd al-Wahhib, after a stay of ten days, from sets out again castle to pursue his gallant exploits (11: Qannasa's 39) he invites her to join him; but she declines, because she is averse to leaving her country. She tenderly kisses him farewell and returns to her castle. This, however, does not mean that she fades from the scene for good. During a later campaign cabd al-WahhAb, having been wounded, is brought to a castle that he recognizes as Qannasa's (II, 20: 77-80). He supposes that she must be long dead and that the situation in the castle But Qannasa will have changed completely. is still there. Her once so radiant beauty has vanished, but her strength, the fatness of her body (shahm badaniha) and her eloquence of speech (fasahat lis6nih6) are still the same; and one glance at cabd al-Wahhab brings back all her love for him. It also turns out that she has born him a son, Zalim. (This is not

229 the only time that cabd al-WahhAb is unexpectedly confronted with the results of a former love affair by meeting a conveniently grown-up son whom he then takes along on his expedition: his meeting with Sayf anthe fruit of a love affair with a Christian princess, is another Nasraniyin, such case (II, 11:80)). Hitherto ZAlim has been ignorant of his descent, and is called ZAlim ibn al-Gharib. There is a happy reunion; Dhat alHimma also turns up, mistakenly fights her grandson, and rejoices in his 'Abd al-Wahhab discovery. After they have spent some time together, wants to continue on his way, taking his son with him. Qannasa agrees, but ZAlim is reluctant (III, 21: 2 ff.), because of a love affair. The problem is soon solved and ZIlim is married. ZAlim as well as QannAsa role in their join the army, and Qannasa does indeed play a prominent next adventure (21: 10 ff.). She is also regularly mentioned during later for instance 36: where IV, 23, episodes, many warriors answer Dhat alHimma's call to battle, among them Qannasa, Nura the wife of al-Battal, 'UlwA, Zannr and the daughters of HayyAj al-Kurdi (also mentioned, for instance, V, 43: 19), and Qannasa does play a prominent part by into with Dhat al-Himma enemy territory sneaking (IV, 36: 37), leaving Nura and Zananir to worry about her; and V, 41: 21, where the Muslim the ladies Qannasa, army swarms out in full battle order, including 'UlwA and Nura. Ghamra, Maymuna, Leiden University REMKE KRUK

BIBLIOGRAPHY antianeirai. Interpretaties van de Amazonenmythe in het mythologisch Blok, J.H. 1991. Amazones onderzoek van de 19e en 20e eeuw in archaischGriekenland. Groningen. Canard, M. 1937. "Delhemma, Sayyid Battl et Omar al-No mn", ByzantionX. Canard, M. "Dh l'Himma", Encyclopaedia of Islam. New edition, Leiden 1960Canard, M. 1961. "Les principaux personnages du roman de chevalerie arabe Dht alHimma wa-1-Battl" . Arabica VIII, 158-73. Canard, M. 1969. "Les reines de Gorgie dans l'histoire et la lgende musulmanes". Revuedes tudesislamiques1969/1, 3-20. Elisseff, N. 1949. Thmeset motifsdes Mille et une Nuits. Essai de classification.Beirut. Ibrhm, Nabla. n.d. Srat al-amra Dht al-Himma. Dirsa muqrina. Cairo. Heath, P. 1984. "A critical review of modern schlarship on Sirat 'Antar ibn Shadddand the popular Sira" . JAL 1984, 19-44. desarabischen die vergleichende Literaturkunde. Heller, B. 1931. Die Bedeutung 'Antar-Romans fr Leipzig. Arabica. Leipzig. Kosegarten, J.G.L. 1825. Chresthomathia Lichtenstdter, I. 1935. Womenin theAiymal-'Arab. A Studyof female life during warfarein preislamicArabia. London. Nchten. Wiesbaden. 6 vols. Littmann, E. 1953. Die Erzhlungenaus den tausendundein

230 arabskiejv swielteeposuSirat al-amra Dt al-Himma a rzecMadeyska, D. 1978. Ideal kobiety historizna("The ideal of the Arab woman in the light of the epic Srat alzywistosc amira Dt al-Himma and the historic reality"). Diss. Warschau. This book, mentioned by K. Patracek in his excellent chapter on "Volkstmliche Literatur" in H. Gtje (ed.), Grundriss der arabischePhilologie,II, pp. 228-41, regrettably was not accessible to me. desarabischenVolksmrchens. Nowak, U. 1969. Beitragezur Typologie Diss., Freiburg i. Br. Oliverius, J. 1971. "Themen und Motiven im arabischen Volksbuch von Zr Salim". Archiv Orientlni39 (1971), 129-45. Hannover. Paret, R. 1924. Srat Saif ibn Dh Jazan. Ein arabischerVolksroman. Paret, R. 1930. Die legendre Maghz-literatur.Tbingen. Paret, R. 1927. Die Ritterromanvon 'Umar an-Nu'mn und seineStellungzur Sammlungvon 1001 Nacht. Tbingen. aus demBeduinenleben untersucht und bersetzt. Schwab, S. 1965. Drei altarabische Erzhlungen Diss. Nrnberg. Sirat al-amraDht al-Himma wa-waladih'Abd al-Wahhbwa-l-amrAb Muhammadal-Battl al-muhtl. Cairo 1327/1909, 7 vols., 70 parts. wa-'Uqba shaykhad-dalll wa-Shmadris Srat fris al-Yaman wa-mubd ahl al-kufr wa-l-mihan al-amr Sayf ibn Dh Yazan. Cairo 1330/1893, 2 vols., 17 parts. zu einemarabischen Steinbach, U. 1972. Dt al-Himma. Kulturgeschichtliche Untersuchungen Volksroman. Wiesbaden. a Classification Thompson, S. 1932-6. Motif-Indexof Folk-Literature: of NarrativeElementsin Folk-tales,Ballads, Myths, Fables, MedievalRomances,Exempla,Fabliaux,Jest-Booksand Local Legends.Bloomington. 6 vols. Walther, W. 1982. "Das Bild der Frau in Tausendundeiner Nacht". HallescheBeitrge der Orientalistik4, 69-91.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Naqab Bedouins: A Century of Politics and ResistanceDa EverandNaqab Bedouins: A Century of Politics and ResistanceNessuna valutazione finora

- Warrior Women in Arabic Popular Romance - Qannâ A Bint Muzâ Im and Other Valiant Ladies PDFDocumento19 pagineWarrior Women in Arabic Popular Romance - Qannâ A Bint Muzâ Im and Other Valiant Ladies PDFFaris Abdel-hadiNessuna valutazione finora

- A Feminist Reading of Selected Poems of Kishwar Naheed: Huzaifa PanditDocumento15 pagineA Feminist Reading of Selected Poems of Kishwar Naheed: Huzaifa PanditShivangi DubeyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Time-Travels of the Man Who Sold Pickles and Sweets: A Modern Arabic NovelDa EverandThe Time-Travels of the Man Who Sold Pickles and Sweets: A Modern Arabic NovelNessuna valutazione finora

- Orientalism and After - Aijaz AhmadDocumento20 pagineOrientalism and After - Aijaz AhmadConor Meleady50% (2)

- White Saris and Sweet Mangoes: Aging, Gender, and Body in North IndiaDa EverandWhite Saris and Sweet Mangoes: Aging, Gender, and Body in North IndiaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (3)

- Contradictions and Lots of Ambiguity Two PDFDocumento21 pagineContradictions and Lots of Ambiguity Two PDFTur111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Monarch of the Square: An Anthology of Muhammad Zafzaf’s Short StoriesDa EverandMonarch of the Square: An Anthology of Muhammad Zafzaf’s Short StoriesMbarek SryfiNessuna valutazione finora

- Women and Islam Fatima Mernisi PDFDocumento238 pagineWomen and Islam Fatima Mernisi PDFrachiiidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Killing Contention: Demobilization in Morocco during the Arab SpringDa EverandKilling Contention: Demobilization in Morocco during the Arab SpringNessuna valutazione finora

- Al Ghazali On The Education of Women PDFDocumento34 pagineAl Ghazali On The Education of Women PDFhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Doing Violence To Ethnography A Response To Catherine Besteman's Representing Violence By: I.M LewisDocumento10 pagineDoing Violence To Ethnography A Response To Catherine Besteman's Representing Violence By: I.M LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNessuna valutazione finora

- An Analysis of Edward Saids OrientalismDocumento4 pagineAn Analysis of Edward Saids OrientalismReynold FrancoNessuna valutazione finora

- Linguistics and Literature Review (LLR) : Humaira RiazDocumento14 pagineLinguistics and Literature Review (LLR) : Humaira RiazUMT JournalsNessuna valutazione finora

- (Spotlight On Shakespeare) Ambereen Dadabhoy - Shakespeare Through Islamic Worlds-Routledge (20Documento265 pagine(Spotlight On Shakespeare) Ambereen Dadabhoy - Shakespeare Through Islamic Worlds-Routledge (20Azan RazaNessuna valutazione finora

- An Analysis of Hybridity in Ahdaf Soueif's WorksDocumento46 pagineAn Analysis of Hybridity in Ahdaf Soueif's WorksLaksmiCheeryCuteiz100% (1)

- Sadik Jalal Al-Azm - Orientalism and Orientalism in ReverseDocumento18 pagineSadik Jalal Al-Azm - Orientalism and Orientalism in ReversecentrosteinNessuna valutazione finora

- Hyphenated Selves - Arab American Women Identity Negotiation in The Works of Contemporary Arab AMerican Women WritersDocumento231 pagineHyphenated Selves - Arab American Women Identity Negotiation in The Works of Contemporary Arab AMerican Women WritersZainab Al QaisiNessuna valutazione finora

- Society (Bulsho) PoemDocumento6 pagineSociety (Bulsho) PoemIbraNessuna valutazione finora

- An Interview With Adib Khan - Bali AdvertiserDocumento3 pagineAn Interview With Adib Khan - Bali AdvertiserPratap DattaNessuna valutazione finora

- Almirath BookDocumento88 pagineAlmirath Bookmosabbeh100% (1)

- Nation and NarrationDocumento1 paginaNation and NarrationLucienne Da CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- An Analysis of Cultural Clash in Tariq Rahman's Charity PDFDocumento12 pagineAn Analysis of Cultural Clash in Tariq Rahman's Charity PDFAbdul HadiNessuna valutazione finora

- Hashi, Bilan - Sexual Desire Modesty and Womanhood - Somali Female Hybrid Subjectivities and The Gabra Xishood Leh Discourse - Uses ShireDocumento143 pagineHashi, Bilan - Sexual Desire Modesty and Womanhood - Somali Female Hybrid Subjectivities and The Gabra Xishood Leh Discourse - Uses Shirejen-leeNessuna valutazione finora

- Amazigh Voice Vol17 n1 PDFDocumento28 pagineAmazigh Voice Vol17 n1 PDFAgidar AmazighNessuna valutazione finora

- Love Poetry (Ghazal) : Qastdah Ranges. in The Introductory Section of The Qastdah, The Nastb, The PoetDocumento17 pagineLove Poetry (Ghazal) : Qastdah Ranges. in The Introductory Section of The Qastdah, The Nastb, The PoetSaad CheemaNessuna valutazione finora

- Webb's Arab Book ReviewDocumento6 pagineWebb's Arab Book ReviewJaffer AbbasNessuna valutazione finora

- Brinkley Messick The Calligraphic State Textual Domination and History in A Muslim Society Comparative Studies On Muslim Societies, No 16 1996Documento323 pagineBrinkley Messick The Calligraphic State Textual Domination and History in A Muslim Society Comparative Studies On Muslim Societies, No 16 1996Fahad BisharaNessuna valutazione finora

- Re Orienting OrientalismDocumento22 pagineRe Orienting OrientalismCapsLock610100% (2)

- An Essay On The Dilemma of Identity and Belonging in Maghrebean Literature, With Examples From Maghrebean WritersDocumento5 pagineAn Essay On The Dilemma of Identity and Belonging in Maghrebean Literature, With Examples From Maghrebean WritersLena FettahiNessuna valutazione finora

- Postcolonial LiteratureDocumento3 paginePostcolonial LiteratureMuhammad Arif100% (1)

- A Seminar Paper On Post ColonialismDocumento12 pagineA Seminar Paper On Post ColonialismAbraham Christopher100% (1)

- The Location of CultureDocumento5 pagineThe Location of CulturePragati ShuklaNessuna valutazione finora

- SeasonOfMigration PDFDocumento19 pagineSeasonOfMigration PDFDa Hyun YuNessuna valutazione finora

- Autobiographical Identities in Contemporary Arab CultureDocumento241 pagineAutobiographical Identities in Contemporary Arab CultureSarahNessuna valutazione finora

- Acculturation and Diasporic Influence in Uma Parmeswaran's "What Was Always Hers" - Anju MeharaDocumento4 pagineAcculturation and Diasporic Influence in Uma Parmeswaran's "What Was Always Hers" - Anju MeharaProfessor.Krishan Bir Singh100% (1)

- Ama AidooDocumento461 pagineAma AidooDana ContrasNessuna valutazione finora

- GSAS PHD Convocation Program - 2013Documento41 pagineGSAS PHD Convocation Program - 2013columbiagsasNessuna valutazione finora

- J 0201247579Documento5 pagineJ 0201247579Lini DasanNessuna valutazione finora

- Faiz Ahmed Faiz - The Rebel's Silhouette - Selected Poems-University Massachusetts Press (1995)Documento126 pagineFaiz Ahmed Faiz - The Rebel's Silhouette - Selected Poems-University Massachusetts Press (1995)Mohammad rahmatullahNessuna valutazione finora

- Sherman Alexie ArticleDocumento17 pagineSherman Alexie ArticleemasumiyatNessuna valutazione finora

- The Crimson Petal and The White by Michel Faber - Discussion QuestionsDocumento2 pagineThe Crimson Petal and The White by Michel Faber - Discussion QuestionsHoughton Mifflin HarcourtNessuna valutazione finora

- The Language Debate in African LiteratureDocumento18 pagineThe Language Debate in African LiteratureAdelNessuna valutazione finora

- Najm Haider Origins of The Shia PDFDocumento298 pagineNajm Haider Origins of The Shia PDFRafah ZaighamNessuna valutazione finora

- Season of Migration To The North CharactDocumento36 pagineSeason of Migration To The North Charactadflkjas;fdja;lkdjf100% (4)

- Mam Amal ProjectDocumento12 pagineMam Amal ProjectAns CheemaNessuna valutazione finora

- Persian LiteratureDocumento6 paginePersian LiteraturefeNessuna valutazione finora

- M.A. English 414Documento442 pagineM.A. English 414निचिकेत ऋषभNessuna valutazione finora

- Re-Configuring FaithDocumento16 pagineRe-Configuring FaithAsha SNessuna valutazione finora

- (Farhad Daftary) Ismailis in Medieval Muslim SocieDocumento272 pagine(Farhad Daftary) Ismailis in Medieval Muslim SocieCelia DanieleNessuna valutazione finora

- Islam Through Western Eyes Edward SaidDocumento9 pagineIslam Through Western Eyes Edward SaidBilal ShahidNessuna valutazione finora

- Church GoingDocumento7 pagineChurch GoingHaroon AslamNessuna valutazione finora

- Arabic Manuscripts of The Thousand and One NightsDocumento2 pagineArabic Manuscripts of The Thousand and One Nightsmjlundell0% (2)

- Clueless EmmaDocumento10 pagineClueless EmmarebeccaNessuna valutazione finora

- Collective SingularsDocumento26 pagineCollective Singularsluan_47Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cloud BustingDocumento3 pagineCloud BustingHana TuhamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Code For GEO MapsDocumento5 pagineCode For GEO MapsHana TuhamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Under The Ivy ChordsDocumento2 pagineUnder The Ivy ChordsHana TuhamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Orientalism IntroductionDocumento15 pagineOrientalism IntroductionHana TuhamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Gershwin George Rhapsody in Blue 31021Documento29 pagineGershwin George Rhapsody in Blue 31021Hana TuhamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Spirited Away - Itsumo Nando DemoDocumento5 pagineSpirited Away - Itsumo Nando DemoHana TuhamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Gershwin George Rhapsody in Blue 31021Documento29 pagineGershwin George Rhapsody in Blue 31021Hana TuhamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Poor Polidori: Granddad of The Romantic VampireDocumento11 paginePoor Polidori: Granddad of The Romantic VampireKira Butler FrazierNessuna valutazione finora

- 《特里斯坦和伊索尔德》书后练习答案Documento0 pagine《特里斯坦和伊索尔德》书后练习答案Jorge Rubilar AstudilloNessuna valutazione finora

- The 20th Century GirlDocumento2 pagineThe 20th Century GirlAtasha BonalosNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Component SPM'13 Form 4 FullDocumento12 pagineLiterature Component SPM'13 Form 4 FullNur Izzati Abd ShukorNessuna valutazione finora

- 18th Century NovelDocumento2 pagine18th Century NovelBiswadeep BasuNessuna valutazione finora

- R P M G 800-1500: Epresentations of Ower IN Edieval ErmanyDocumento38 pagineR P M G 800-1500: Epresentations of Ower IN Edieval ErmanyKirillNessuna valutazione finora

- Frithiof's Saga PDFDocumento252 pagineFrithiof's Saga PDFEsteban ArangoNessuna valutazione finora

- Vampire News PDFDocumento100 pagineVampire News PDFBertena VarneyNessuna valutazione finora

- Rizal Family and FriendsDocumento53 pagineRizal Family and Friendsglorigreiz100% (1)

- 30 Flirty Questions To Ask A GirlDocumento17 pagine30 Flirty Questions To Ask A GirlLandel Smith100% (2)

- Scholastic Triumphs at Ateneo de Manila (1872-1877)Documento66 pagineScholastic Triumphs at Ateneo de Manila (1872-1877)naitsircedoihr villatoNessuna valutazione finora

- Examen ExtraDocumento3 pagineExamen ExtraDelia BeltránNessuna valutazione finora

- Welsh NamesDocumento5 pagineWelsh NamesPetra Gabriella PatakiNessuna valutazione finora

- A Day Without TechnologyDocumento6 pagineA Day Without TechnologyRenztot Yan EhNessuna valutazione finora

- Historical Romance Novels - Historical Fiction RomanceDocumento2 pagineHistorical Romance Novels - Historical Fiction RomanceJo0% (1)

- All For Lov1Documento2 pagineAll For Lov1CreatnestNessuna valutazione finora

- Genre Gothic BookletDocumento28 pagineGenre Gothic BookletOrmo@Normo100% (1)

- Bear, Otter, and The Kid (Bear, Otter, and The Kid, #1)Documento17 pagineBear, Otter, and The Kid (Bear, Otter, and The Kid, #1)LaurieNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature: Genres of LiteratureDocumento5 pagineLiterature: Genres of LiteratureBianca Jane AsuncionNessuna valutazione finora

- Zingaro LyricsDocumento4 pagineZingaro LyricsChris PineNessuna valutazione finora

- The Tale of The Three Brothers PDFDocumento1 paginaThe Tale of The Three Brothers PDFdanacream100% (2)

- ST Valentines Day WebquestDocumento4 pagineST Valentines Day WebquestAngel Angeleri-priftis.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Stephen KingDocumento237 pagineStephen KingFranz Edric Bangalan100% (9)

- Untitled 2Documento19 pagineUntitled 2Afrilia CahyaniNessuna valutazione finora

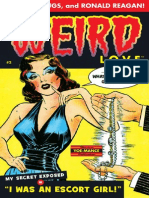

- WEIRD Love #2 PreviewDocumento10 pagineWEIRD Love #2 PreviewGraphic Policy100% (2)

- Realism and Naturalism in Nineteenth C AmericaDocumento249 pagineRealism and Naturalism in Nineteenth C America1pinkpanther99Nessuna valutazione finora

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnet 22Documento2 pagineElizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnet 22api-270897909100% (9)

- English Literature and FolkloreDocumento41 pagineEnglish Literature and FolkloreClélia GurdjianNessuna valutazione finora

- ALICE EssayDocumento11 pagineALICE Essaylopezortizlaura100% (1)

- The Biarritz Vacation AND The Romance With Nellie BousteadDocumento7 pagineThe Biarritz Vacation AND The Romance With Nellie BousteadEamacir UlopganisNessuna valutazione finora