Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

A Corpus-Based Study of Units of Translation in English-Persian Literary Translations

Caricato da

Abbas GholamiDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A Corpus-Based Study of Units of Translation in English-Persian Literary Translations

Caricato da

Abbas GholamiCopyright:

Formati disponibili

~ -

-`=

-- - - -=- - - - _- = - -=

~ - Considering this notion from a product-oriented point of view as "the TT unit

that can be mapped onto a ST unit" (Baker, 200! 2"#$, the researcher%s main

concern is to investigate a hierarch& of units of trans'ation ((Ts$ proposed b&

)ewmark (**! ##-#"$ inc'uding word, phrase, c'ause, sentence, and paragraph in

the 'iterar& trans'ations+ ,t the pre'iminar& stage, two -uestions were raised to

detect the most fre-uent (T adopted b& the professiona' 'iterar& trans'ators, and to

e.p'ore the re'ationship between the (Ts and the free-'itera' dichotom& in terms of

the occurrence of unit/rank shifts+ To this end, a corpus of three famous 0ng'ish

nove's (origina''& written in 0ng'ish b& the renowned authors$ and two best-se''ing

trans'ations of each (done b& professiona' trans'ators$ were chosen to be ana'&1ed+

Through a contrastive ana'&sis, two hundred and ten coup'ed pairs of ST-TT

segments were e.tracted from the first ten pages of each nove' and its two

trans'ations based on estab'ishing re'ations of e-uiva'ence between the ST-TT

segments and adopting sentence as the ma2or unit of ana'&sis+ The (Ts adopted in

the ST-TT segments were then identified+ The obtained resu'ts of the (T categories

demonstrated that the most fre-uent (T adopted b& the professiona' 'iterar&

trans'ators was sentence+ The unit-shifts app'ied in the (Ts were a'so signified+ The

statistica' ca'cu'ation of fre-uenc& of unit-shifts in each trans'ator%s (Ts proved that

the more fre-uent is the occurrence of unit-shifts in the (Ts of the trans'ator, the

more deviated is his trans'ation from the forma' correspondence, the more different

the si1e of his (Ts is, and fina''& the freer his trans'ation wi'' be .

Key Words! Descriptive Translation Studies (DTS), units oI translation, Iree-literal

dichotomy, unit/rank shiIts, equivalence, Iormal correspondence .

1 . Introduction

Translation Studies is a new discipline which is concerned with the study oI theory

and phenomena oI translation. A classical concern Ior translation theory which is

1

Irequently mentioned in older literature on the subject is the level at which

equivalence should be established, i.e. what units oI translation one should choose

during the translation process. CatIord (1965:21) suggests that the goal oI translation

theory is to deIine the nature oI translation equivalence. To him ,

The central problem oI translation practice is that oI Iinding TL translation

equivalents. A central task oI translation theory is that oI Iinding the nature and

conditions oI translation equivalents .

In translation studies, much discussion in the translation literature has Iocused on

identiIying what should be equivalent in a translation. For example, with regard to

the linguistic Iorm, discussion in translation literature has Iocused on whether

equivalence is to be pursued at the level oI words, clauses, phrases, sentences,

paragraphs, or the entire text. Accordingly, this has given rise to the emergence oI

the concept oI Translation Units which is one oI the key concepts in translation

theory that has exercised translation theorists over a very long period. In the Iield oI

translation, Irom a product-oriented approach, a translation unit is a segment oI a

target text which the translator treats as a single cognitive unit. The translation unit

may be a single word, or it may be a phrase, a clause, a sentence, or even a larger

unit like a paragraph .

In translation studies, the issue oI UT is Irequently raised in conjunction with that oI

translation equivalence. As Sager (1994: 222) puts it, both 'lie at the heart oI any

theoretical or practical discussion about translation. This is because theorists,

consciously or unconsciously, take the UT as a compartment in which what they

believe to be 'translation equivalence materializes .

There is a point in establishing equivalence, Toury believes, only insoIar as it can

serve as a stepping stone to uncovering the overall concept oI translation underlying

the corpus it has been Iound to pertain to; besides, the notion oI equivalence may

also Iacilitate the explanation oI the entire network oI translational relationship and

the individual coupled pairs as representing actual translation units under the

dominant norm oI translation equivalence (1995: 86). In this regard, one oI the tasks

oI the researcher wishing to probe into the translation units is to establish the

equivalent relationships between the coupled pairs of ST and TT segments which

can pave the way Ior the identiIication and classiIication oI units oI translation at

diIIerent levels. In other words, to investigate unit(s) oI translation that the translator

2

chooses during the translation process, one needs to establish a relation oI

equivalence between the ST and the TT .

In earlier work on translation equivalence, CatIord (1965: 20) deIines translation as

"the replacement oI textual material in one language (SL) by equivalent textual

material in another language (TL)". He distinguishes textual equivalence Irom

Iormal correspondence, which are respectively called by Nida as dynamic

equivalence and Iormal equivalence .

, forma' correspondent is "any TL category (unit, class, structure, element oI

structure, etc.) which can be said to occupy, as nearly as possible, the "same"

place in the "economy" oI the TL as the given SL category occupies in the SL ."

, te.tua' e-uiva'ent is "any TL text or portion oI text which is observed on a

particular occasion. to be the equivalent oI a given SL text or portion oI text"

(ibid: 27 ( .

It is worth mentioning, however, that departures from formal correspondence

between the source and target texts denote Translation Shifts (ibid: 73), the

investigation oI which has a long-standing tradition in translation studies. In other

words, shifts are deviations or changes that occur at every level during the

translation process as a result of the systemic differences between the source and

target languages .

There has been a great argument among theorists about the length (size) oI unit oI

translation. For most oI them, the length oI translation units is an indication oI

proIiciency, with proIessional translators working with larger units (sentence,

discourse, or text) and moving more comIortably between diIIerent unit levels. This

controversial argument about the length oI unit oI translation is, according to

Newmark (1988: 54), a concrete reIlection oI an age-old conIlict between Iree and

literal translation: The Ireer the translation the longer the UT, the more literal the

translation; the shorter the UT, the closer to the word. ThereIore, despite major shiIts

oI viewpoint on translation, one oI the oldest as well as the most decried conIlicts in

translation has been the concept oI literal versus Iree translation, or the distinction

between word-Ior-word translation and sense-Ior-sense translation. The controversy

over literal versus free translation has a long history, with convincing supporters

on each side .

3

In this research, the issue oI units oI translation is approached Irom a product-

oriented viewpoint to seek answers Ior the two Iollowing two questions :

RQ

1

: What is the most Irequent UT among the proIessional translators oI the

Iamous English novels ?

RQ

2

: What is the relationship between the UTs and the kinds oI translation,

i.e. Iree vs. literal, adopted by the proIessional literary translators in terms oI

the occurrence oI unit-shiIts ?

2 . Theoretical Discussions

2.1Descriptive Translation Studies (DTS (

A branch oI Translation Studies, developed in most detail by Toury (1995), that

involves the empirical, non-prescriptive analysis oI STs and TTs with the aim oI

identiIying general characteristics and laws oI translation (Hatim and Munday, 2004:

338). According to Munday (2001: 10-11), DTS is a branch oI 'pure' research in

Holmes's map oI Translation Studies and has three possible Ioci: examination oI the

product, the Iunction, and the process .

2.2 Translation Units

According to Baker (2001: 286), the term 'unit oI translation', considered Irom a

product-oriented approach, is deIined as "the TT unit that can be mapped onto a ST

unit ."

Newmark (1991: 66-68) assumes the main translation units to be a hierarchy: text,

paragraph, sentence, clause, group, word, and morpheme .

2.3 Equivalence

Baker (2001: 77) deIines equivalence as the relationship between a ST and a TT that

allows the TT to be considered as a translation oI the ST in the Iirst place. Vinay and

Darbelnet view equivalence-oriented translation as a procedure which "replicates the

same situation as in the original, whilst using completely diIIerent wording" (cited in

Shuttleworth and Cowie, 1997: 51 ( .

2.4 Dynamic/Textual equivalence vs. ormal equivalence

4

DeIined by Nida (1964, cited in Bassnett, 1980: 33), the Iormer (also known as

Iunctional equivalence) is "the closest natural equivalent to the source-language

message" (ibid: 166) and attempts to convey the thought expressed in a source text

(at the expense oI literalness, original word order, the source text's grammatical

voice, etc., iI necessary); while the latter (also known as Iormal correspondence)

attempts to render the text word-Ior-word (at the expense oI natural expression in the

target language, iI necessary). Also, deIined by CatIord (1965: 27), the Iormer (also

known as textual equivalence) is "any TL text or portion oI text which is observed

on a particular occasion to be the equivalent oI a given SL text or portion oI text"

and the latter is "any TL category (unit, class, structure, element oI structure, etc.)

which can be said to occupy, as nearly as possible, the same place in the economy oI

the TL as the given SL category occupies in the SL ."

2.5 S!i"t

As Iar as translation shiIts are concerned, CatIord (1965: 73) deIines them as

"departures Irom Iormal correspondence in the process oI going Irom the SL to the

TL", i.e. if translational equivalents are not formal correspondent. According to Al-

Zoubi and Al-Hassnawi (2001: 2), shifts should be defined positively as the

consequence of the translator's effort to establish translation equivalence (TE)

between two different language systems. To them, shifts are all the mandatory and

optional actions of the translator to which s/he resorts consciously for the purpose of

natural and communicative rendition of an SL text into another language (ibid ( .

2.6 Unit/ran# s!i"t

CatIord (1965: 79) deIines unit/rank shiIts as those departures Irom Iormal

correspondence in which "the translation equivalent oI a unit at one rank in the SL is

a unit at a diIIerent rank in the TL ."

2.7 $iteral Translation

Literal or word-Ior-word translation is deIined by Robinson as "the segmentation oI

the SL text into individual words and TL rendering oI those word-segments one at a

time" (1998, cited in Baker, 2001: 125). A literal translation can be deIined in

linguistic terms as a translation "made on a level lower than is suIIicient to convey

5

the content unchanged while observing TL norms" (Barkhudarov, 1969, cited in

Shuttleworth and Cowie, 1997: 95). In a similar vein, CatIord also oIIers a deIinition

based on the notion oI the UT: literal translation takes word-Ior-word translation as

its starting point, although because oI the necessity oI conIorming to TL grammar,

the Iinal TT may also display group-group or clause-clause equivalence (1965: 25 .(

2.8 ree Translation

Also known as sense-Ior-sense translation, it is a type oI translation in which more

attention is paid to producing a naturally reading TT than to preserving the ST

wording intact (Shuttleworth and Cowie, 1997: 62). Linguistically, it can be deIined

as a translation "made on a higher level than is necessary to convey the content

unchanged while observing TL norms" (Barkhudarov, 1969: 11, translated, cited in

ibid). In other words, the UT in a Iree translation might be anything up to a sentence

(or more) even iI the content oI the ST in question could be reproduced satisIactorily

by translating on the word or group level (ibid). Besides, according to CatIord (1965:

25), it is a prerequisite oI Iree translations that they should also be unbounded as

regards the rank (or level) on which they are perIormed. Free translations are thus

generally more TL-oriented than literal translations .

3 . Methodology

Through conducting this research, an attempt has been made to investigate the

argument about the problematic nature oI units oI translation in relation to Iree and

literal translations adopted in English-Persian literary translations regarding the unit-

shiIts. Put it in another way, the present research seeks to study translation units that

the proIessional literary translators adopt in the process oI translating Iamous novels

Irom English into Persian, and it is carried out by establishing a relation (oI

equivalence) between the coupled pairs of ST and TT segments (that is to say, to

ascertain whether the translated literary texts are the closest natural equivalent to the

original message (Nida's deIinition oI translation, 1964: 166), i.e. dynamically

equivalent, or Iormally equivalent), while taking into account the dichotomy oI Iree-

literal approach to translation in terms oI the occurrence oI unit-shiIts in the UTs. So

the approach is limited inasmuch as the researcher has looked at Units oI Translation

only Irom the angle oI the product oI translation .

6

As a consequence, this research is placed within the Iramework oI Pure Translation

Studies-in Holmes's map oI translation studies (Toury, 1995: 10, cited in Munday,

2001: 10-12) -which actually has Descriptive Translation Studies (DTS) as one oI its

major branches. In Iact, DTS embarks upon examination oI the product, the Iunction

and the process as three Iocal points among which the Iirst one is highlighted in the

course oI this research. Since this study is concerned with the product oI translation

and is a comparative analysis oI several TTs oI the same ST, it is a "Descriptive"

research. Stated by Farhady, "Through descriptive method, researchers attempt to

describe and interpret the current status oI phenomena" (2001: 144). Descriptive

research is deIined by Birjandi and Mosallanejad (2002: 184-86) as the basis Ior

qualitative research that deals with what is happening now .

So the design oI this research is "descriptive" content analysis. Moreover, this

research goes under the heading oI "Qualitative". A qualitative research explains

how all parts work together to Iorm a whole. Patten deIines qualitative research as

"an eIIort to understand situations in their uniqueness as part oI a particular context.

It is not attempting to predict what may happen in the Iuture, but to understand the

nature oI the setting" (cited in Birjandi and Mosallanejad, 2002: 76-7 ( .

Moreover, through several subcategories Farhady (2001: 144, 154) represents Ior

descriptive method oI research, "Casual-Comparative" method which is, in turn, a

subcategory oI "interrelational" methods seemed the most appropriate to the

researcher to conduct this research. The research is by nature comparative in that it is

aimed at comparing and contrasting pairs of ST and TT segments so as to find the

most frequent UT among the professional literary translators and to trace and

discover the relationship between their UTs and the kinds of translation, i.e. free vs.

literal, applied by them in terms of the occurrence of unit-shifts in UTs in the move

Irom the ST to the TT. Thus, it can be found out that this study falls under a

comparative category for research method .

3.1 %orpus Selection &rocedure

In order Ior the samples oI this research to meet the representativeness criterion, i.e.

to be representative oI the whole population, the selection oI materials was based on

a non-random samp'ing criterion which is described by Farhady (2001: 212) as a

process oI choosing research population when random sampling is not possible. For

7

the sake oI choosing certain English-Persian literary works, both the source texts and

the target texts were selected based on a purposive samp'ing which is, according to

Farhady (ibid: 212), a procedure Ior selecting a non-random sampling, and deIined

by him as "the procedure directed toward obtaining a certain type oI members with

predetermined characteristics" (ibid ( .

Taking all these criteria into account, the novels and the translations oI each were

meticulously selected. These were then supposed to be segmented, compared and

contrasted Irom the viewpoint oI units oI translation. Indeed, the corpus used in this

study is a para''e' corpus, that is to say, original English source texts and their

translations in Persian. A parallel corpus is defined by Olohan (2004: 24) as "a

corpus consisting of a set of texts in one language and their translations in another

language ."

The English novels were selected based on purposive samp'ing to IulIill the

Iollowing selection criteria ,

Originally written in English ,

Being regarded as masterpieces ,

Closely related to each other in terms oI genre, and

Written by renowned authors .

Persian translations were also selected based on purposive samp'ing to include those

consistent with the Iollowing certain criteria :

Best-selling Persian translations ,

Being considered as the pick oI the numerous existing translations, and

Done by proIessional translators .

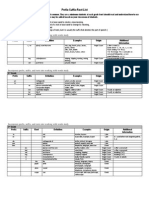

The Iinal samples are presented in Tables 1 & 2 .

Table 1 The list oI English novels

No . Novel Title Author Year oI the First

Edition

Selected

Pages

1

Heart oI Darkness Joseph Conrad

1899 1-10

2

Lord oI the Flies William olding

1954 1-10

3

Cry, the Beloved

Country

Alan Paton

1948 1-10

8

The list oI Persian Translations Table 2

Persian Translations oI Heart oI Darkness

No . Title Translator Year oI the

First Edition

Year oI

Publication

Selected

Pages

1 - - - 1985 2001 1-10

2

- 1986 1986 1-10

Persian Translations oI Lord oI the Flies

No . Title Translator Year oI the

First Edition

Year oI

Publication

Selected

Pages

1 - - =

(.)

1984 1984 1-10

2

(~)

1984 1984 1-10

Persian Translations oI Cry, the Beloved Country

No . Title Translator Year oI the

First Edition

Year oI

Publication

Selected

Pages

1 = -- 1972 1982 1-10

2 -

-=

-~

1983 2004 1-10

3.2 Data %ollection &rocedure

In order to manage the process oI data collection, the Iirst ten pages oI each novel

and their Persian translations were selected. Then, to make a thorough comparison

between the STs and their selected TTs possible, the Iirst two hundred and ten

sentences Irom those ten pages oI each novel were extracted. The extracted

9

sentences oI each novel were then matched with their two translations. In this way,

the ST-TT segments were speciIied Ior each novel based on the established

equivalent relations. The ST-TT segments extracted Irom each novel and its two

translations were then included in the separate tables related to each novel. Here, a

point to mention is that the researcher had to adopt a unit oI analysis to make it

possible to speciIy ST-TT segments and later to make it Ieasible to identiIy the UTs

applied in each segment and, hence, to discover the occurrence oI unit-shiIts in those

UTs .

1 ( So, the Iirst stage was to speciIy the ST segments. For that matter, sentence was

basically adopted as the major unit oI analysis. Because it is mainly regarded as a

meaningIul unit that conveys the message completely. Besides, among the language

levels the sentence is where sentence linguistics and text linguistics overlap, and

decisions made at any other language levels will be duly reIlected within the contour

oI the sentence, the primary building block Ior TL text construction (Hewson and

Martin, 1991: 86). However, the researcher encountered some rare cases in each ST

(novel) where a complete message was conveyed through a word or phrase, so she

considered word or phrase as the minor units oI analysis. Moreover, in order to

speciIy the ST segments the researcher had to stick to a punctuation mark to separate

the units oI analysis; thereIore, she essentially used Iull stops to separate the ST

sentences. Because among punctuation signs that operate to (con)textualize, Iull

stops are the most signiIicant marks since they signal the Iull sentential

independence oI a language segment (Zhu, 1996: 438 .(

2 ( Yet, aIter speciIication oI the ST segments as mentioned above, the two

translations oI each ST segment were speciIied in the next stage. Since the

translations were supposed to be speciIied based on the established equivalent

relation between the ST and the TT, the translation column in the tables is entitled

equivalent translation, which is to CatIord (1965: 27) 'an empirical phenomenon,

discovered by comparing SL and TL texts. Also, it was important to the researcher

whether the translation was Iormally equivalent, i.e. directed more towards the Iorm

oI the ST or Iormal correspondence, or dynamically equivalent which is described as

"the closest natural equivalent to the source-language message" (Nida, 1964: 166).

The researcher actually regarded it as a basis to later enable identiIication oI the

occurrence oI unit-shiIts in speciIied UTs .

10

3.3 Data 'nalysis &rocedure

AIter speciIying the ST-TT segments, they had to be analyzed to see what UT(s)

were applied in them by each translator. One source oI inspiration Ior choosing the

units oI translation was Newmark (1991: 66-68)'s statement that assumes the main

translation units to be a hierarchy: text, paragraph, sentence, clause, phrase/group,

word, and morpheme. Yet, in order to increase the degree oI manageability oI the

research, an attempt was made to select those UTs which are Irequently preIerred as

basic working UTs by the translators. ThereIore, in ascending order, word, phrase,

clause, sentence and paragraph were selected as categories oI UT .

3.3.1 (nvesti)atin) Units o" Translation

3.3.1.1 Word as UT* It is clear that, despite its apparent convenience, the word on its

own is unsuitable Ior consideration as the basis Ior a unit oI translation. Further,

although the researcher has been mostly concerned with the sentence as unit oI

analysis, there were in Iact some rare cases in each story where the researcher had to

regard word as UT, because the translator could have successIully conveyed the

message to the reader through one word in TT, as in the Iollowing cases :

Heavens =

That's right . . -

Tomorrow, she said . .

3.3.1.2 &!rase as UT* Hatim and Mason (1990: 180) maintain that there is no doubt

that translators work with phrases as their raw material, and equivalence cannot truly

be established at these levels. Phrase is considered as "two or more words that

Iunction together as a group" (Swan, 2005: xxii) and conveys a thorough message

per se, as in the Iollowing cases :

Old knitter oI black wool . - --

" Sucks to your ass-mar " . `

This letter, Stephen . - - - .

3.3.1.3 %lause as UT* Syntactically clause Iorms a part oI a sentence and has a

subject-predicate structure which is not complete by itselI and is semantically

11

dependent (Richards and Platt, 1992: 52-53); thereIore, it is not a meaningIul unit

and should be completed by another sentence. So this UT has not been separately

observed. In Iact, the clauses were taken into account in the Iorm oI sentences

incorporating them, i.e. comp'e. sentences- which contain one or more dependent (or

subordinate) clauses and an independent (or main) clause- and compound-comp'e.

sentences- which contain two or more independent clauses and one or more

dependent clauses (Frank, 1972: 1 ( .

In the present study, the clauses have been taken into consideration under two

broader constituent categories, i.e. complex sentence or compound-complex

sentence. Also, the number oI both complex sentences and compound-complex

sentences is considered as indicative oI clause as UT .

3.3.1.3.1 %lause as UT* %omplex Sentences* As deIined by Frank (1972: 1),

complex sentence contains one or more dependent (or subordinate) clauses and an

independent (or main) clause. For example :

They were men enough to Iace the darkness . - - -~ -

.~ -

" I expect there's a lot more oI us scattered about . - - =

.~ `

There is a lovely road that runs Irom Ixopo into the hills . - - ---

.

3.3.1.3.2 %lause as UT* %ompound+%omplex Sentences* DeIined by Frank (1972:

1), compound-complex sentence contains two or more independent (or main) clauses

and one or more dependent (or subordinate) clauses. For example :

It was the biggest thing in the town, and everybody I met was Iull oI it .

.~ _`= ` -` ~ ~ - - --

When he gets leave he'll come and rescue us . = - - -= -- =-

.

For there there is a multitude oI buses, and only one bus in ten, one bus in twenty maybe, is

the right bus . . - - - - ~ -- - - - =

- -

12

3.3.1.4 Sentence as UT* According to Richards and Platt (1992: 330), sentence is

the largest unit oI grammatical organization within which parts oI speech (e.g.

nouns, verbs, adverbs) and grammatical classes (e.g. word, phrase, clause) Iunction,

and a sentence normally consists oI one independent clause with a Iinite verb. Also,

according to Frank (1993: 220), a sentence is a Iull, independent prediction

containing a subject plus a predicate in the Iorm oI independent clause. Elsewhere he

deIines the independent clause as a Iull prediction that may stand alone as a sentence

|222|. Based on the independent clause(s) consisting sentences, the sentences can be

generally classiIied into two types: simple and compound, both oI which contain

independent clause as their only building block. So this UT was treated in simp'e

sentences and compound sentences, and the number oI both simple sentences and

compound sentences is reckoned as indicative oI UT as sentence .

3.3.1.4.1 Sentence as UT* Simple Sentences* To Frank (1972: 1), simple sentence

contains one Iull subject and predicate and can take the Iorm oI a statement, a

question, a request, or an exclamation. Such a sentence has only one Iull prediction

in the Iorm oI an independent clause (Frank, 1993: 222). For example :

His remark did not seem at all surprising . - - -

.- -=

Piggy bore this with a sort oI humble patience . -- - - - =

. =

It is not an easy letter . .

3.3.1.4.2 Sentence as UT* %ompound Sentence: As stated by Frank (1972: 1),

compound sentence contains two or more sentences joined into one by punctuation

alone, punctuation and a conjunctive adverb, or a coordinate conjunction; when such

sentences are joined coordinately, they are each called independent clause. Such

sentences have two or more Iull predictions in the Iorm oI independent clauses (ibid,

1993: 222). For example :

I gave my name, and looked about . . - - - -

Ralph giggled into the sand . = -

.--=

She took the letter and she Ielt it . . ~=

13

3.3.1.5 &ara)rap! as UT* DeIined by Richards and Platt (1992: 262), paragraph is a

unit oI organization oI written language, which serves to indicate how the main ideas

in a written text are grouped. In text linguistics, paragraphs are considered as macro-

structure oI a text and they group sentences which belong together and deal with the

same topic. Consequently, a paragraph, as a macro-structure, usually consists oI a

group oI related sentences such as simple, compound, complex, or compound-

complex which together incorporate a whole unit. Yet, in this study, paragraph as

UT was Iound to be exclusively implemented in the both translations oI 3eart of

4arkness by the same number, and no cases oI such UT were Iound in the both

translations oI the two other stories. For example :

And at last, in its curved and imperceptible Iall, the sun sank low, and Irom glowing white

changed to a dull red without rays and without heat, as iI about to go out suddenly, stricken

to death by the touch oI that gloom brooding over a crowd oI men .

~- - - - = ~= -

~ - - = - =-- - ~- = ` - _ - =

.- -

3.3.2 (nvesti)atin) Unit+s!i"ts in t!e UTs 'pplied ,y t!e Translators

Based on the categories mentioned above, the UTs applied in the ST-TT segments

were identiIied. Concurrently, while identiIying the UTs in the ST-TT segments,

unit/rank shiIts or those departures Irom Iormal correspondence in which "the

translation equivalent oI a unit at one rank in the SL is a unit at a diIIerent rank in the

TL" (CatIord, 1965: 79) were also sought aIter. The unit-shiIts were speciIied to

later gauge the relationship between the UT and the Iree-literal dichotomy .

Apparently, according to CatIord, shiIt is not Iormally equivalent. In Iact, iI the SL is

imitated exactly in the TL, the result is called Iormally equivalent translation which

is awkward or unnatural, more directed towards the Iorm oI the ST, and basically

source-oriented. However, to avoid such a translation, the translator may deviate

Irom the ST and move away Irom close linguistic equivalence, so a shiIt occurs and

the resulting translation distancing Irom Iormal correspondence (equivalence) is

called dynamically (textually) equivalent translation which is described as "the

closest natural equivalent to the source-language message" (Nida, 1964: 166 ( .

14

The kind oI shiIt which is taken into account in the current study is unit/rank shift

that is a subdivision oI category shiIt and is deIined by CatIord (1965, cited in

Munday, 2001: 61) as the shiIt "where the translation equivalent in the TL is at a

diIIerent rank to the SL", as in the Iollowing cases :

ShiIt UT Equivalent Translation English

yes

Phrase ~ s.s . .- - = Dead in the centre .

yes s.s. ~ cx. s . - -

.-~ -`

For a moment he looked

interested .

yes s.s. ~ cd. s . - - Look at it .

4 . Discussion of Findings and Conclusions

While analyzing the collected data, it seemed logical to calculate the Irequency and

percentage oI units oI translation applied in the three novels as well as the Irequency

and percentage oI unit-shiIts in the UTs adopted by the proIessional translators oI

those novels. Based on the Iindings oI the analysis, the results oI the statistical

analysis are presented in the Iollowing tables :

Table 3 Frequency and Percentage oI Units oI Translation in 3eart of 4arkness,

5ord of the 6'ies, and Cr&, the Be'oved Countr&

Total

Percentage

Percentage Total

Frequenc

y

Frequenc

y

Sub-

categories

oI

Units oI

Translation

Units oI

Translation

1.81 1.81 24 24 Word

3.27 3.27 44 44 Phrase

43.18 29.48

580

396 Complex

Sentence

Clause

13.70 184 Compound-

complex

sentence

51.45 31.19

691

419 Simple

Sentence

Sentence

15

20.25 272 Compound

Sentence

0.29 0.29 4 4 Paragraph

As Table 3 reveals, the most Irequently applied unit oI translation among the literary

translators is the sentence which remarkably includes the majority oI samples, the

highest Irequency as well as the highest percentage which ranks sentence as the top

list category and the Ioremost adopted unit oI translation. In addition, clause

covering a wide range oI samples and having an approximately high Irequency and

percentage occupies the second prominent position among the applied units oI

translation. Lastly, phrase, word and paragraph are respectively other applied units

oI translation whose Irequency and percentage are not highly signiIicant. A summary

oI the statistical Iindings obtained in this section is presented in the Iollowing chart :

Units Of Translation

43.18

51.45

1.81

0.29

3.27

sentence

Paragraph

Word

Phrase

Clause

This leads to the conclusion that successIul literary translators are mostly concerned

with the sentence as their unit oI translation to Iind the closest natural equivalent to

the source-language message and to best convey the message to the TL reader .

Table 4 Frequency and Percentage oI shiIts in the UTs in 3eart of 4arkness, 5ord

of the 6'ies, and Cr&, the Be'oved Countr&

Novels Translators Frequency 7ercentage

Hosseini's Translation 88 41.90

16

3eart of

4arkness

Hajati's Translation 97 46.19

5ord of the 6'ies

Azad's Translation 75 35.71

Ardekani's Translation 98 46.66

Cr&, the Be'oved

Countr&

Daneshvar's Translation 77 36.66

HaIezipoor's Translation 88 41.90

Since the occurrence oI unit-shiIts, as departures Irom Iormal correspondence in the

UTs in the move Irom SL to TL, is the Iocus oI study in this section, here the

Irequency and percentage oI shiIts occurred in the UTs oI each translator have been

calculated separately to make the comparison possible. As indicated in Table 4, unit-

shiIt has occurred most Irequently in Ardekani's translation oI 5ord of the 6'ies, so it

contains the highest percentage. Also, in Hajati's translation oI 3eart of 4arkness a

nearly similar number oI unit-shiIts has occurred. It can be representative oI the Iact

that these two translators are highly oriented towards deviating Irom the ST,

applying translation units oI a size diIIerent Irom the ST, and, thus, their translations

tend to be Ireer. The obtained results have been displayed in the Iollowing graph :

17

It can be inIerred that, as Iar as the product-oriented view oI the UTs is concerned,

the more Irequent is the occurrence oI shiIts in the UTs oI the translator, the more

deviated is his/her translation Irom the Iormal correspondence, the more diIIerent the

size oI his/her UTs is, and Iinally the Ireer his translation will be. Thus, there is a

direct relationship between the number oI occurrence oI shiIts in the units oI

translation (i.e. unit-shiIts) and Iree translation. Besides, although Irequency oI the

occurrence oI unit-shiIts is closely related to a Iree translation being produced and it

may make a translation Ireer, it may change the size oI the UTs to a longer or shorter

UT; so Ior the UTs it is the matter oI either/or .

5 . inal Words

The Iindings, theoretical discussions, as well as practical evidences oI this research

can provide guidelines Ior the novice translators who need to gain the initial

knowledge to take the preliminary steps. Also, the results oI this study may introduce

some usable hints on the application oI the most appropriate UT in the literary

translation Ior university students majoring in translation and translation courses.

Since the most Irequently applied UT among the literary translators proved to be the

'sentence', grammar exercises and translation tasks on grammatical structures can be

used in translation classes. For IulIilling such a purpose, teachers had better use a

grammar-oriented approach in their translation classes, especially in courses such as

translation principles and methodology, as well as translation oI simple texts in

general and literary texts in particular. This is due to the Iact that the ST segments

can have a deep structure and a surIace structure whose identiIication can help apply

the UT that is true equivalence oI the ST and best Iits the translation oI literary texts .

Furthermore, based upon the relationship Iound in this research between the UTs and

the Iree-literal dichotomy in terms oI the unit-shiIts, the translation trainees can be

instructed that application oI unit-shiIts in the process oI going Irom the ST to the

TT helps them to achieve a Iree translation and that the literary translation needs to

undergo deviations Irom the Iormal correspondence to meet this requirement .

At the end, given the importance oI application oI the most appropriate UT in the

literary translations, a need is Ielt Ior IulIilling Iurther researches into the domain oI

UT and it is hoped that this study paves the way Ior other studies in this area .

18

Wor#s %ited

Al-Zoubi, M. Q. and A. R. Al-Hassnawi (2001). Constructing a Model Ior ShiIt

Analysis in Translation. Trans'ation 8ourna'+ Retrieved December 10,

2006 Irom the World Wide Web:

http://accurapid.com/journal/18theory.htm

Baker, M. (2001). The 9out'edge 0nc&c'ooedia of Trans'ation Studies. London:

Routledge .

Bassnett, S. (1980/1991). Trans'ation Studies. London and New York:

Routledge

Birjandi, P. and P. Mosallanejad (2002). 9esearch :ethods and 7rincip'es.

Tehran, Iran: Shahid Mahdavi Publications .

CatIord, J. C. (1965): , 5inguistic Theor& of Trans'ation. London: OxIord

University Press .

Farhady, H. (1995). 9esearch methods in app'ied 'inguistics+ Tehran: Payame

Noor University .

Frank, M. (1972). :odern 0ng'ish! 0.ercises for non-native speakers, 7art ;;.

United States oI America: Prentice-Hall .

) ------- 1993 .( :odern 0ng'ish! , 7ractica' 9eference <uide. United States oI

America: Prentice-Hall .

Hatim, B. and I. Mason (1990). 4iscourse and the Trans'ator. London and

New York: Longman .

Hatim, B. and J. Munday (2004). Trans'ation! ,n advanced resource book+

Routledge: New York .

Hewson, L. and J. Martin (1991). 9edefining Trans'ation! The =ariationa'

,pproach. London and New York: Routledge .

19

Munday, J. (2001). ;ntroducing trans'ation studies! theories and app'ications+

London & New York: Routledge .

Newmark, P. (1988). , Te.tbook of Trans'ation. New York, London: Prentice

Hall .

) ------ 1991 .( ,bout Trans'ation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters .

Nida, E. A. (1964). Toward a Science of Trans'ating+ Leiden: E. J. Brill .

Olohan, M. (2004). Introducing Corpora in Translation Studies. London and

New York, Routledge .

Richards, J. C., J. Platt and H. Platt (1992). 4ictionar& of 5anguage Teaching

and ,pp'ied 5inguistics. reat Britain: Longman .

Sager, J. (1994). 5anguage 0ngineering and Trans'ation Conse-uences of

,utomation. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins .

Shuttleworth, M. and M. Cowie (1997). Dictionary oI Translation Studies.

Manchester: St. Jerome .

Swan, M. (2005). 7ractica' 0ng'ish Usage. 3

rd

ed. New York: OxIord

University Press .

Toury, . (1995). 4escriptive Trans'ation Studies and Be&ond. Amsterdam and

Philadelphia: John Benjamins .

Zhu, C. (1996). 'Climb Up and Look Down: On sentences as the key

Iunctional UT (Unit OI Translation) in text translation, 7roceedings of

the >th ?or'd Congress of the 6@d@ration ;nternationa'e des

Traducteurs (6;T$, February 1996, Vol. 1, Melbourne, AUSIT, pp. 322-

343 .

20

It can be representative oI the Iact that the deviations Irom the ST have been

considerably high in these two translations, UTs oI a diIIerent size Irom the ST have

been applied, and they tend to be Ireer .

This study sets out, amid the points already mentioned, a method Ior the comparison

oI ST and TT pairs: identifying the relationships between the coupled pairs of ST

and TT segments and establishing equivalence and attempting generalizations about

the underlying concept of unit of translation to explore what UT is most Irequently

adopted by the proIessional literary translators and to argue the relationship between

the UTs and the Iree-literal dichotomy in terms oI the occurrence oI unit/rank shiIts

or changes in the UTs in the move Irom the ST to the TT .

21

Hence, in line with Newmark's hypothesis, this product-oriented descriptive

translation research intends to enrich the theory oI describing the phenomenon oI

English-Persian literary translation Irom the viewpoint (perspective) oI units oI

translation: to investigate the most Irequent unit oI translation applied by the

proIessional literary translators, and to inquire into the relationship between the UT

and the kind oI translation, i.e. Iree vs. literal, adopted by the literary translators in

terms oI unit shiIt .

This paper tries to draw a clear picture oI the notion oI Unit oI Translation as a key

concept in translation studies. In so doing, it is argued by the researcher that the

development oI the issue oI UT inevitably involves a theory oI equivalence, which

can be said to be the central issue in translation. It also sheds light on the distinction

between literal translation and Iree translation, which is an important and ever

debated point in the literature oI translation, in terms oI the occurrence oI unit/rank

shiIts or changes in the UTs in the move Irom the ST to the TT, and in a corpus oI

literary translations Irom English into Persian (outstanding novels originally written

in English and their successIul translations done by proIessional translators ( .

To this end, the researcher has been mainly concerned with comparing the SL and

TL texts (certain literary translations with their original texts) so as to highlight the

diIIerences between proIessional literary translators concerning the two points noted

above. The comparison oI texts in two diIIerent languages Ior the purpose oI

speciIying units oI translation inevitably involves a Iocus on equivalence which is

the central issue in translation. So this study also aims to ascertain whether the

translated literary texts are Iormally equivalent, i.e. directed more towards the Iorm

22

oI the ST or Iormal correspondence, or dynamically equivalent which is described as

"the closest natural equivalent to the source-language message" (Nida, 1964: 166 ( .

To achieve the above-mentioned goals, the researcher aims to look into three Iamous

English novels considered as masterpieces and to compare and contrast ten pages oI

each novel with two oI its successIul translations done by proIessional translators.

Through conclusions which will be drawn at the end oI the analysis and implications

which will be provided Ior Iurther studies, it is hoped that new insights can be

oIIered to the literary translators

Individual translators, with diIIerent Ioci oI attention, may preIer diIIerent units as

their basic working UTs .

It is widely agreed to be the case that translation and translation studies have never

had it so good. Over the last two or three decades, translation has become a more

proliIic, more visible and more respectable activity than perhaps ever beIore. And

alongside translation itselI, a new Iield oI academic study has come into existence,

initially called Translatology (but not Ior long) which is now changed into

Translation Studies, and it has gathered remarkable academic momentum .

The concept oI UT (unit oI translation) has been an essential issue not only in

translation theory over the last years, but also in modern translation studies

In this light, Vinay and Darbelnet (1958/95) maintain that Ior any science, one oI the

essential and oIten the most controversial preliminary steps is deIining the units with

which to operate (cited in Hatim and Munday, 2004: 137). This is equally true oI

translation .

23

It is axiomatic that, despite its apparent convenience, the word on its own is

unsuitable Ior consideration as the basis Ior a unit oI translation .

According to Newmark (1988: 30-31), normally you translate sentence by sentence

(not breath-group by breath-group), running the risk oI not paying enough attention

to the sentence-join. II the translation oI a sentence has no problems, it is based

Iirmly on literal translation, plus virtually automatic and spontaneous transpositions

and shiIts, changes in word order, etc. He Iurther argues that "since the sentence is

the basic unit oI thought, presenting an object and what it does, is, or is aIIected by,

so the sentence is, in the Iirst instance, your unit oI translation, even though you may

later Iind many SL and TL correspondences within that sentence" (31 .(

.

Unit oI translation is an issue that has exercised translation theorists over a very long

period, indeed. The issue oI unit oI translation is oI a paramount importance in the

study oI translation in general and the translation oI literary works in particular :

It might illustrate the kind oI translation adopted in the process oI translating, i.e.

Irom the dichotomy oI literal-Iree translation which has dominated translation theory

Ior a very long time; it helps to explore the nature oI the notion oI equivalence, a key

concept which is basic to any linguistically oriented translation theory, in that every

translation has to stand in some kind oI equivalence relation to the original and this

equivalence relation, which is anything but clear-cut and predictable, is the outcome

oI the workings on Units oI Translation; it can also be indicative oI the translation

shiIts or changes that take place in the move Irom ST to TT and the perception oI

which triggers a sort oI adjustment mechanism that ensures the correct interpretation

oI the message .

It is generally deIined as the study oI the theory and phenomena oI translation. It is,

according to many researchers in the Iield, an emerging discipline, yet to gain the

status oI an independent and distinct discipline in the academia around the world .

Translation studies, as an umbrella term, maniIests that translation has been

practiced Ior thousands oI years, and debates on the nature oI translation have been

part oI translation practice Ior almost as long. The debates on translation practice go

back to the very deIinition oI what translation is .

SL emphasis TL emphasis

Word-Ior-word translation Adaptation

24

Literal translation Free translation

FaithIul translation Idiomatic translation

Semantic translation Communicative translation

Figure 2.1. Types oI Translation according to Newmark (1988: 45 (

His model shows that word-Ior-word translation, Ior example, is the closest in Iorm

to the original structure oI the source text; whereas adaptation puts the most

emphasis on the Iluency oI the target text. He Iurther sheds light on each oI these

translation methods as Iollows :

Stated by Hatim and Munday (2004: 255), it is Peter Newmark's 'semantic

translation' that has come closest to what Iormal equivalence might entail. In

semantic translation, the translator attempts, within the bare syntactic and semantic

constraints oI the TL, to reproduce the precise contextual meaning oI the author

(1988: 22, cited in ibid ( .

In this light, Munday (2001: 44) maintains that Newmark's description oI

communicative translation resembles )ida%s d&namic e-uiva'ence in the eIIect it is

trying to create on the TT reader, while semantic translation has similarities to

)ida%s forma' e-uiva'ence. Yet, Newmark keeps himselI away Irom the Iull principle

oI equivalent eIIect, since that eIIect "is inoperant iI the text is out oI the TL space

and time" (1981: 69, cited in ibid). He Iurther indicates that semantic translation

diIIers Irom literal translation in that it 'respects context', interprets and even

explains; on the other hand, literal translation means word-Ior-word translation

which sticks very closely to ST lexis and syntax (1981: 63, cited in ibid).

Nevertheless, he considers literal translation to be the best approach in both semantic

and communicative translation :

Translation may be deIined as the replacement oI textual material in one language

(SL) by equivalent textual material in another language (TL). The central problem oI

translation practice is that oI Iinding TL translation equivalents. A central task oI

translation theory is that oI deIining the nature and conditions oI translation

equivalence (CarIord, 1965: 21). Chesterman (1989: 99) notes that equivalence is

obviously a central concept in translation theory. To Kenny (1997: 77), equivalence

is supposed to deIine translation, and translation, in turn, deIines equivalence .

25

As stated by Bassnett (1980: 32-33), Albercht Neubert, who distinguishes between

the study oI translation as a process and as a product, stresses the need Ior a theory

oI equivalence relations as the missing link between both components oI a

complete theory oI translation, while Raymond van den Broeck challenges the

extensive use oI the term claiming that the precise deIinition oI equivalence in

mathematics is a serious obstacle to its use in translation theory

However, according to the concept oI this Iundamental translation term, which is

somehow diIIerent Irom that oI the linguistic term oI 'correspondence', translating is

not merely replacing the words oI the ST with their corresponding words in the TL.

In this respect, Munday (2001: 49) quotes Bassnett as saying :

Translation involves Iar more than replacement oI lexical and grammatical items

between languages ... Once the translator moves away Irom close linguistic

equivalence, the problem oI determining the exact nature oI the level oI equivalence

aimed Ior begin to emerge (Bassnett, 1980/91: 25 ( .

CatIord (1965, cited in Shuttleworth and Cowie, 1997: 51) views equivalence as

something essentially quantiIiable- and translation as simply a matter oI replacing

each SL item with the most suitable TL equivalent .

This perception has led some scholars to subdivide the notion oI equivalence in

various ways. Thus, some have distinguished between the equivalence Iound at the

levels oI diIIerent units oI translation, while others have Iormulated a number oI

equivalence typologies, such as Nidas (1964) inIluenced dynamic and Iormal

equivalence, Each oI these individual categories oI equivalence which will be

elaborated through the upcoming paragraphs encapsulates a particular type oI ST-TT

relationship .

Pointed out by CatIord (1965: 27), and Sarhady (Trans'ation Studies, 7 & 8 (2004 &

2005): 67-68), Irom a linguistic approach, a distinction must be made between

textual equivalence and Iormal correspondence. A textual equivalence is any TL text

or portion oI text which is observed on a particular occasion to be the equivalent oI a

given SL text or portion oI text. A Iormal correspondence, on the other hand, is any

TL category which can be said to occupy, as neatly as possible, the same place in the

economy oI the TL as the given SL category occupies in the SL. Since every

language is a unique system, it seems that Iormal correspondence is approximate. To

CatIord (ibid), the degree oI divergence between textual equivalence and Iormal

26

correspondence may be used as a measure oI typological diIIerences between

languages .

Eugene Nida (1964) distinguishes two types oI equivalence, Iormal and dynamic,

and proposes them as two basic orientations in translating .

In Iormal equivalence, the Iocus oI attention is on the message itselI, in both Iorm

and content, and one is concerned that the message in the receptor language should

match as closely as possible the diIIerent elements in the source language. Thus, it is

basically source-oriented; that is it is designed to reveal as much as possible oI the

Iorm and content oI the original message. Such a translation in which one is

concerned with such correspondences as poetry to poetry, sentence to sentence, and

concept to concept is called by Nide a 'gloss translation', which aims to allow the

reader to understand as much oI the SL context as possible (Nida, 1964, cited in

Venuti, 1995:136 ( .

To have a Iormal equivalence, one attempts to reproduce several Iormal elements,

including grammatical units, consistency in word usage, and meanings in terms oI

the source context. ThereIore, correspondence in grammatical units, such as

translating nouns by nouns, verbs by verbs, etc., keeping all phrases and sentences

intact, and preserving lexical concordance are oI the characteristics oI Iormal

equivalence (ibid ( .

However, in dynamic equivalence, the Iocus oI attention is directed, not so much

toward the source message, as toward the receptor response. A dynamic equivalence

translation may be described as one concerning which a bilingual and bicultural

person can justiIiably say, "That is just the way we would say it". One way oI

deIining the dynamic equivalence translation is to describe it as "the closest natural

equivalent to the source-language message" (ibid ( .

It is assumed by Hatim and Munday (2004: 44) that :

The more Iorm-bound a meaning is., the more Iormal the equivalence relation will

have to be. Alternatively, the more context-bound a meaning is ., the more

dynamic the equivalence will have to be .

FE Meaning ~~~~~~~DE

FORM- BOUND CONTEXT- BOUND

Figure 2.6 Formal (FE) vs. dynamic (DE) equivalence (ibid ( .

Accordingly, Iormal equivalence presupposes matching SL- and TL- content, which

is a very reasonable requirement iI it is supposed to hold Ior suIIiciently large units,

27

and at the same time matching Iorms- the most IaithIul rendering possible oI the

word order, parts oI speech, grammatical constructions and also genre-determined

Iorm (meter, etc) oI the SL-text (Pederson, 1988: 18 ( .

To Hatim and Mason (1990: 7), although Iormal equivalence is a means oI providing

some degree oI insight into the lexical, grammatical or structural Iorm oI a source

text; orientation towards dynamic equivalence, on the other hand, is assumed to be

the normal strategy. As claimed by Nida (1964: 160, cited in ibid), "the present

direction is toward increasing emphasis on dynamic equivalences. Indeed, he deIines

the goal oI dynamic equivalence as seeking the "closest natural equivalent to the

source-language message" (Nida, 1964: 166, Nida and Taber, 1969: 12 ( .

Viewing the UT as a language level on which translation equivalence is to be

established is a misguided conception based on three unwarranted belieIs: (a) UT is a

Iormal unit in nature and can be treated in isolation; (b) language units are automatic

UTs; and (c) complete equivalence is achievable (Zhu, 1996: 433 ( .

reveals Newmark's apparent vacillation about the range oI the UT. Elsewhere he has

stressed the importance oI the sentence, conspicuously absent in the above

deIinition, as the "natural" or primary UT, while those below the sentence are "sub-

units oI translation" (Newmark, 1988: 31, 65 ( .

Importantly, Newmark (1988: 66-7) makes the crucial point that "all lengths oI

language can, at diIIerent moments and also simultaneously, be used as units oI

translation in the course oI the translation activity". While, as mentioned by Hatim

and Munday (2004: 25), it may be that the translator most oIten works at the

sentence level, paying speciIic attention to the problems raised by individual words

or groups in that context. However, to Newmark (1988: 69), the longer the unit, the

rarer one-to-one translation in which each SL word has a corresponding TL word .

As distinctly pointed out by Newmark (1988: 30-31), since sentence is the basic unit

oI thought, so it is your unit oI translation, even though you may later Iind many SL

and TL correspondences within that sentence. Normally you translate sentence by

sentence (not breath-group by breath-group), running the risk oI not paying enough

attention to the sentence-joins. Indeed, primarily you translate by the sentence, and

in each sentence, it is the object and what happens to it that you sort out Iirst.

Additionally, he (ibid: 65) insists that the sentence is the 'natural' unit oI translation,

just as it is the natural unit oI comprehension and recorded thought .

28

Newmark (1991: 66-68) assumes the main descriptive units to be a hierarchy: text,

paragraph, sentence, clause, group, word, and morpheme .

Hatim and Mason (1990: 180) maintain that there is no doubt that translators work

with words and phrases as their raw material, and equivalence cannot truly be

established at these levels .

Sometimes the translator is compelled to translate a part oI his/her material with a

change/shiIt in the unit oI translation such as the time when s/he encounters cases oI

untranslatability in which a number oI items are Iound in the text Ior which there is

no corresponding equivalence or even the nearest equivalence in the TL and decides

to render those parts using a Iree or communicative method oI translation. Texts tend

to be identiIied as translations when shiIts Irom source-language text are perceived.

The perception oI these shiIts triggers in the addressee a sort oI adjustment

mechanism which ensures the correct interpretation oI the message .

Actually, CatIord was the Iirst scholar to use the term in his , 5inguistic Theor& of

Trans'ation (1965, cited in Hatim and Munday, 2001: 26). In CatIord's own words,

translation shiIts are "departures Irom Iormal correspondence in the process oI going

Irom the SL to the TL" (1965: 73 .(

According to Munday, CatIord (1965: 20) Iollows the Firthian and Hallidayan

linguistic model, which analyzes language as communication, operating Iunctionally

in context and on a range oI diIIerent levels (e.g. phonology, graphology, grammar,

lexis) and ranks (sentence, clause, group, word, morpheme, etc.) (Munday, 2001:

60 ( .

Baker (2001: 226-227) deIines shiIt as changes that occur in the process oI

translating. ShiIts are deemed as required, inevitable, and indispensable changes

which result Irom attempts to deal with the systemic diIIerences which exist between

source and target languages and cultures. ShiIts allow the translators to overcome

such diIIerences .

Also, Venuti (2000: 148) regards shiIts as 'deviations' that can occur at such

linguistic levels as graphology, phonology, grammar, and lexis. Further, he clariIies

that when Anton Popovic asserts that "shiIts do not occur because the translator

wishes to change a work, but because he strives to reproduce it as IaithIully as

possible", the kind oI "IaithIulness" he has in mind is "Iunctional", with the

translator locating "suitable equivalents in the milieu oI his time and society"

(Popovic, 1970: 80, 82, cited in ibid ( .

29

As Iar as the product-oriented view oI shiIts is concerned, Popovic (1970: 79, cited

in Baker, 2001: 228) deIines shiIts Irom a descriptive point oI view :

All that appears as new with respect to the original, or Iails to appear where it might

have been expected, may be interpreted as a shiIt .

Popovic also comments that shiIts represent "the relationship between the wording

oI the original work and that oI the translation" (Popovic, 1970: 85, cited in

Shuttleworth and Cowie, 1997: 153 ( .

As pointed out by Newmark (1988: 85, 285), 'shiIt' also termed by Vinay and

Darbelnet as 'transposition' is a translation procedure involving a change in the

grammar Irom SL to TL .

Within the Iramework oI a linguistic theory oI translation, CatIord (1965: 27)

distinguishes between Iormal correspondence and textual equivalence, which was

later to be developed by Koller :

' "ormal correspondent is "any TL category (unit, class, structure, element oI

structure, etc.) which can be said to occupy, as nearly as possible, the "same" place

in the "economy" oI the TL as the given SL category occupies in the SL ."

' textual equivalent is "any TL text or portion oI text which is observed on a

particular occasion. to be the equivalent oI a given SL text or portion oI text ."

Munday (2001: 60) maintains that textual equivalence is thus tied to a particular ST-

TT pair and Iocuses on the relations that exit between elements in a speciIic ST-TT

pair. While Iormal equivalence has to do with general, non-speciIic and system-

based relationships between a pair oI languages or elements in two languages. When

the two concepts diverge, a translation shiIt is deemed to have occurred. To Haim

and Munday (2004: 28), a shiIt occurs iI, in a given TT, a translation equivalent

other than the Iormal correspondent occurs Ior a speciIic SL element .

MT!"D"#"$%

, there is considerable disagreement among translation theorists investigating the

notion oI units oI translation on the level at which equivalence should be established,

i.e. what units to choose as Units oI Translation. In the Iield oI translation, Irom a

product-oriented approach, a translation unit is a segment oI a target text which the

translator treats as a single cognitive unit. The translation unit may be a single word,

or it may be a phrase, a clause, a sentence, or even a larger unit like a paragraph .

30

This controversial argument about the length oI unit oI translation is, according to

Newmark (1988:45), a concrete reIlection oI an age-old conIlict between Iree and

literal translation. The Ireer the translation, the longer the UT; the more literal the

translation, the shorter the UT, the closer to the word .

The present research seeks to study translation units that the proIessional literary

translators adopt in the process oI translating Iamous novels Irom English into

Persian and it is carried out by establishing a relation (oI equivalence) between the

coupled pairs of ST and TT segments (that is to say, to ascertain whether the

translated literary texts are the closest natural equivalent to the original message

(Nida's deIinition oI translation, 1969: 19), i.e. dynamically equivalent, or Iormally

equivalent), while taking into account the dichotomy oI Iree-literal approach to

translation in terms oI the occurrence oI unit-shiIts in the UTs. So the approach is

limited inasmuch as the researcher has looked at Units oI Translation only Irom the

angle oI the product oI translation .

As a consequence, this research is placed within the Iramework oI Pure Translation

Studies-in Holmes's map oI translation studies (Toury, 1995: 10, cited in Munday,

2001: 10-12) -which actually has Descriptive Translation Studies (DTS) as one oI its

major branches. In Iact, DTS embarks upon examination oI the product, the Iunction

and the process as three Iocal points among which the Iirst one is highlighted in the

course oI this research :

1 . &roduct'oriented DT( intends to describe or analyze the existing translations

and address a single ST-TT pair or a comparative analysis oI several TTs oI the same

ST .

31

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Gregg Reference ManualDocumento345 pagineGregg Reference ManualEndi Ubaedillah75% (8)

- Summary of Latin Verbs - Active VoiceDocumento1 paginaSummary of Latin Verbs - Active VoiceJennifer Jones100% (5)

- G4 Q1 W5 DLLDocumento7 pagineG4 Q1 W5 DLLMark Angel MorenoNessuna valutazione finora

- WER 2013 7b Waste To EnergyDocumento14 pagineWER 2013 7b Waste To EnergyAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Teacher Efficacy Capturing An Elusive ConstructDocumento23 pagineTeacher Efficacy Capturing An Elusive ConstructAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Combustion of ChemicalDocumento10 pagineCombustion of ChemicalAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Teacher Efficacy Capturing An Elusive ConstructDocumento23 pagineTeacher Efficacy Capturing An Elusive ConstructAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Why More SuccessDocumento4 pagineWhy More SuccessAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Why More SuccessDocumento4 pagineWhy More SuccessAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching EfficacyDocumento8 pagineTeaching EfficacyAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Why More SuccessDocumento4 pagineWhy More SuccessAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Why More Success P PDFDocumento5 pagineWhy More Success P PDFAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- English Education in IranDocumento7 pagineEnglish Education in IranAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Implicit and Explicit InformationDocumento3 pagineImplicit and Explicit InformationAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- A Corpus-Based Study of Units of Translation in English-Persian Literary TranslationsDocumento31 pagineA Corpus-Based Study of Units of Translation in English-Persian Literary TranslationsAbbas GholamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Write The Missing Words of The Verb To Be (Affirmative Form)Documento1 paginaWrite The Missing Words of The Verb To Be (Affirmative Form)Romina PomboNessuna valutazione finora

- Tenses Based On Functional GrammarDocumento2 pagineTenses Based On Functional GrammarSejin's GlassesNessuna valutazione finora

- Guía Primer Parcial Inglés 5Documento18 pagineGuía Primer Parcial Inglés 5Mayte LópezNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Sentence PatternsDocumento9 pagineBasic Sentence PatternsnaeyahNessuna valutazione finora

- DLP Q3W6 Day 1Documento10 pagineDLP Q3W6 Day 1Judette GuerraNessuna valutazione finora

- Causative Verbs HandoutsDocumento4 pagineCausative Verbs HandoutsAdrian ó h-éalaitheNessuna valutazione finora

- List of Adverbs PDFDocumento1 paginaList of Adverbs PDFJavier PajuñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prefix and Suffix Root ListDocumento6 paginePrefix and Suffix Root ListbiffinNessuna valutazione finora

- A Brief Swedish GrammarDocumento344 pagineA Brief Swedish Grammarkurt_stallings100% (1)

- Russian Pronouns - Russian GrammarDocumento5 pagineRussian Pronouns - Russian GrammarHimanshu Singh100% (1)

- On The Origin of Grammatical GenderDocumento6 pagineOn The Origin of Grammatical GenderMar AlexNessuna valutazione finora

- English Grammar A1 Level Possessive Case - English Grammar A1 Level PrintDocumento2 pagineEnglish Grammar A1 Level Possessive Case - English Grammar A1 Level PrintBooks for languagesNessuna valutazione finora

- Cleft SentencesDocumento8 pagineCleft SentencesGilda FarinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Position of French Adverbs: LessonDocumento3 paginePosition of French Adverbs: LessonDeboNessuna valutazione finora

- DI I9 CTU1 T3 VoBo 110320Documento5 pagineDI I9 CTU1 T3 VoBo 110320JESSICA GONZALEZ MENDEZNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary - Grammar Basic Points Units 1-6Documento33 pagineSummary - Grammar Basic Points Units 1-6alesales89Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vocabulary of Biliau, An Austronesian Language of New GuineaDocumento55 pagineVocabulary of Biliau, An Austronesian Language of New GuineamalaystudiesNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 - Noun PhrasesDocumento5 pagine2 - Noun PhrasesThuý HạNessuna valutazione finora

- Syntax 7-8Documento42 pagineSyntax 7-8NuriNessuna valutazione finora

- TOEFL Preparation SyllabusDocumento6 pagineTOEFL Preparation SyllabusalamNessuna valutazione finora

- Dixson Robert J Tests and Drills in English GrammarDocumento193 pagineDixson Robert J Tests and Drills in English GrammarChinara0% (1)

- Written Expression QuestionsDocumento10 pagineWritten Expression Questionsaufa faraNessuna valutazione finora

- You DesuDocumento6 pagineYou DesuOmar E PerezNessuna valutazione finora

- Gerunds and InfinitivesDocumento10 pagineGerunds and InfinitivesAdella SisiNessuna valutazione finora

- Regular Verbs - Mosaic 4 Infinitive Present Simple Simple Past Past Participle /t/-/d/-/id/ - Ing Form TranslationDocumento2 pagineRegular Verbs - Mosaic 4 Infinitive Present Simple Simple Past Past Participle /t/-/d/-/id/ - Ing Form TranslationJaime FalaganNessuna valutazione finora

- Gerunds - InfinitivesDocumento6 pagineGerunds - Infinitiveslan đỗ thịNessuna valutazione finora

- Abdulfetah Nesha, Word Formation in Kafinoonoo Language, MA Thesis, Addis Ababa University, EthiopiaDocumento97 pagineAbdulfetah Nesha, Word Formation in Kafinoonoo Language, MA Thesis, Addis Ababa University, EthiopiaLeonel RamirezNessuna valutazione finora