Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Fressel V Mariano

Caricato da

bbbmmm1230 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

44 visualizzazioni5 pagineThis is an appeal from a judgment sustaining the demurrer on the ground that the complaint does not state a cause of action, followed by an order dismissing the case after the plaintiffs declined to amend. The complaint, omitting the caption, etc., reads: "the plaintiffs demanded of the defendant the return or permission to enter upon said premises and retake said materials at the time still unused"

Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Fressel v Mariano

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

DOC, PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoThis is an appeal from a judgment sustaining the demurrer on the ground that the complaint does not state a cause of action, followed by an order dismissing the case after the plaintiffs declined to amend. The complaint, omitting the caption, etc., reads: "the plaintiffs demanded of the defendant the return or permission to enter upon said premises and retake said materials at the time still unused"

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOC, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

44 visualizzazioni5 pagineFressel V Mariano

Caricato da

bbbmmm123This is an appeal from a judgment sustaining the demurrer on the ground that the complaint does not state a cause of action, followed by an order dismissing the case after the plaintiffs declined to amend. The complaint, omitting the caption, etc., reads: "the plaintiffs demanded of the defendant the return or permission to enter upon said premises and retake said materials at the time still unused"

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato DOC, PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 5

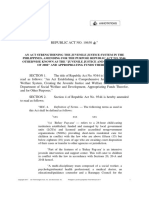

G.R. No.

L-10918

March 4, 1916

WILLIAM FRESSEL, ET AL., plaintiffs-appellants,

vs.

MARIANO UY CHACO SONS & COMPANY, defendant-appellee.

Rohde and Wright for appellants.

Gilbert, Haussermann, Cohn and Fisher for appellee.

TRENT, J.:

This is an appeal from a judgment sustaining the demurrer

on the ground that the complaint does not state a cause of

action, followed by an order dismissing the case after the

plaintiffs declined to amend.

The complaint, omitting the caption, etc., reads:

2. That during the latter part of the year 1913, the

defendant entered into a contract with one E. Merritt,

whereby the said Merritt undertook and agreed with the

defendant to build for the defendant a costly edifice in

the city of Manila at the corner of Calle Rosario and

Plaza del Padre Moraga. In the contract it was agreed

between the parties thereto, that the defendant at any

time, upon certain contingencies, before the completion

of said edifice could take possession of said edifice in

the course of construction and of all the materials in

and about said premises acquired by Merritt for the

construction of said edifice.

3. That during the month of August land past, the

plaintiffs delivered to Merritt at the said edifice in the

course of construction certain materials of the value of

P1,381.21, as per detailed list hereto attached and

marked Exhibit A, which price Merritt had agreed to pay

on the 1st day of September, 1914.

4. That on the 28th day of August, 1914, the defendant

under and by virtue of its contract with Merritt took

possession of the incomplete edifice in course of

construction together with all the materials on said

premises including the materials delivered by plaintiffs

and mentioned in Exhibit A aforesaid.

5. That neither Merritt nor the defendant has paid for

the materials mentioned in Exhibit A, although payment

has been demanded, and that on the 2d day of

September, 1914, the plaintiffs demanded of the

defendant the return or permission to enter upon said

premises and retake said materials at the time still

unused which was refused by defendant.

6. That in pursuance of the contract between Merritt

and the defendant, Merritt acted as the agent for

defendant in the acquisition of the materials from

plaintiffs.

The appellants insist that the above quoted allegations show

that Merritt acted as the agent of the defendant in

purchasing the materials in question and that the defendant,

by taking over and using such materials, accepted and

ratified the purchase, thereby obligating itself to pay for the

same. Or, viewed in another light, if the defendant took over

the unfinished building and all the materials on the ground

and then completed the structure according to the plans,

specifications, and building permit, it became in fact the

successor or assignee of the first builder, and as successor

or assignee, it was as much bound legally to pay for the

materials used as was the original party. The vendor can

enforce his contract against the assignee as readily as

against the assignor. While, on the other hand, the appellee

contends that Merritt, being "by the very terms of the

contract" an independent contractor, is the only person

liable for the amount claimed.

It is urged that, as the demurrer admits the truth of all the

allegations of fact set out in the complaint, the allegation in

paragraph 6 to the effect that Merritt "acted as the agent for

defendant in the acquisition of the materials from plaintiffs,"

must be, at this stage of the proceedings, considered as

true. The rule, as thus broadly stated, has many limitations

and restrictions.

A more accurate statement of the rule is that a

demurrer admits the truth of all material and relevant

facts which are well pleaded. . . . .The admission of the

truth of material and relevant facts well pleaded does

not extend to render a demurrer an admission of

inferences or conclusions drawn therefrom, even if

alleged in the pleading; nor mere inferences or

conclusions from facts not stated; nor conclusions of

law. (Alzua and Arnalot vs. Johnson, 21 Phil. Rep., 308,

350.)

Upon the question of construction of pleadings, section 106

of the Code of Civil Procedure provides that:

In the construction of a pleading, for the purpose of

determining its effects, its allegations shall be liberally

construed, with a view of substantial justice between

the parties.

This section is essentially the same as section 452 of the

California Code of Civil Procedure. "Substantial justice," as

used in the two sections, means substantial justice to be

ascertained and determined by fixed rules and positive

statutes. (Stevens vs. Ross, 1 Cal. 94, 95.) "Where the

language of a pleading is ambiguous, after giving to it a

reasonable intendment, it should be resolved against the

pleader. This is especially true on appeal from a judgment

rendered after refusal to amend; where a general and

special demurrer to a complaint has been sustained, and the

plaintiff had refused to amend, all ambiguities and

uncertainties must be construed against him." (Sutherland

on Code Pleading, vol. 1, sec. 85, and cases cited.)

The allegations in paragraphs 1 to 5, inclusive, above set

forth, do not even intimate that the relation existing

between Merritt and the defendant was that of principal and

agent, but, on the contrary, they demonstrate that Merritt

was an independent contractor and that the materials were

purchased by him as such contractor without the

intervention of the defendant. The fact that "the defendant

entered into a contract with one E. Merritt, where by the said

Merritt undertook and agreed with the defendant to build for

the defendant a costly edifice" shows that Merritt was

authorized to do the work according to his own method and

without being subject to the defendant's control, except as

to the result of the work. He could purchase his materials

and supplies from whom he pleased and at such prices as he

desired to pay. Again, the allegations that the "plaintiffs

delivered the Merritt . . . . certain materials (the materials in

question) of the value of P1,381.21, . . . . which price Merritt

agreed to pay," show that there were no contractual

relations whatever between the sellers and the defendant.

The mere fact that Merritt and the defendant had stipulated

in their building contract that the latter could, "upon certain

contingencies," take possession of the incompleted building

and all materials on the ground, did not change Merritt from

an independent contractor to an agent. Suppose that, at the

time the building was taken over Merritt had actually used in

the construction thus far P100,000 worth of materials and

supplies which he had purchased on a credit, could those

creditors maintain an action against the defendant for the

value of such supplies? Certainly not. The fact that the

P100,000 worth of supplies had been actually used in the

building would place those creditors in no worse position to

recover than that of the plaintiffs, although the materials

which the plaintiffs sold to Merritt had not actually gone into

the construction. To hold that either group of creditors can

recover would have the effect of compelling the defendants

to pay, as we have indicated, just such prices for materials

as Merritt and the sellers saw fit to fix. In the absence of a

statute creating what is known as mechanics' liens, the

owner of a building is not liable for the value of materials

purchased by an independent contractor either as such

owner or as the assignee of the contractor.

The allegation in paragraph 6 that Merritt was the agent of

the defendant contradicts all the other allegations and is a

mere conclusion drawn from them. Such conclusion is not

admitted, as we have said, by the demurrer.

The allegations in the complaint not being sufficient to

constitute a cause of action against the defendant, the

judgment appealed from is affirmed, with costs against the

appellants. So ordered.

Arellano, C.J., Torres, Johnson and Araullo, JJ., concur.

Moreland, J., concurs in the result.

Carson, J., dissents.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Law Relating To InjunctionsDocumento8 pagineLaw Relating To InjunctionsAzeem Rasic NabiNessuna valutazione finora

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionDa EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Motion To Dismiss - Capacity US Bank - PITA NoA Cost BondDocumento16 pagineMotion To Dismiss - Capacity US Bank - PITA NoA Cost Bondwinstons2311100% (2)

- v1. Motion To Declare Defendant in DefaultDocumento4 paginev1. Motion To Declare Defendant in DefaultRhows Buergo67% (3)

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaDa EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (4)

- In Re Julian CDDocumento2 pagineIn Re Julian CDjetzon2022Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ethics Case StudyDocumento9 pagineEthics Case StudyMaria Sheilo SenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Order To Show CauseDocumento20 pagineOrder To Show CauseOCEANA_HOANessuna valutazione finora

- Law of TortsDocumento25 pagineLaw of TortsSabyasachi GhoshNessuna valutazione finora

- Nature of The CaseDocumento3 pagineNature of The CaseJenin VillagraciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes in Statcon - 2019Documento5 pagineNotes in Statcon - 2019AJ DimaocorNessuna valutazione finora

- Compilation of Case Digests in SpecPro (Batch2 Cases)Documento23 pagineCompilation of Case Digests in SpecPro (Batch2 Cases)Anonymous QsEO85Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyDa EverandCape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Citation: G.R. No. L-10918 Date: Petitioners: Respondents: Doctrine: Antecedent FactsDocumento1 paginaCase Citation: G.R. No. L-10918 Date: Petitioners: Respondents: Doctrine: Antecedent FactsCarie LawyerrNessuna valutazione finora

- SALES - Valles v. VillaDocumento2 pagineSALES - Valles v. VillaAnonymous iScW9l50% (2)

- Agency DigestDocumento31 pagineAgency DigestRuperto A. Alfafara IIINessuna valutazione finora

- Linan V PunoDocumento4 pagineLinan V Punobbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- FRESSEL VS MARIANO UY CHACO SONS & Co PDFDocumento1 paginaFRESSEL VS MARIANO UY CHACO SONS & Co PDFClee Ayra CarinNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. L-28379 March 27, 1929 The Government of The Philippine Islands, ApplicantDocumento6 pagineG.R. No. L-28379 March 27, 1929 The Government of The Philippine Islands, Applicantbbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sales CasesDocumento38 pagineSales CasesPrincess Cue Aragon100% (1)

- Parañaque Kings Enterprises, Inc. Vs Court of Appeals 268 SCRA 727. February 26, 1997Documento2 pagineParañaque Kings Enterprises, Inc. Vs Court of Appeals 268 SCRA 727. February 26, 1997Gerard Relucio OroNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 Tsai v. CADocumento2 pagine4 Tsai v. CAStephanie SerapioNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Sikat v. Vda. de VillanuevaDocumento7 pagine5 Sikat v. Vda. de VillanuevaShairaCamilleGarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Spouses Trinidad V ImsonDocumento4 pagineSpouses Trinidad V ImsonCrmnmarie100% (1)

- Commercial Law 11 DR Caroline Mwaura NotesDocumento16 pagineCommercial Law 11 DR Caroline Mwaura NotesNaomi CampbellNessuna valutazione finora

- Fortunato Gomez V CADocumento3 pagineFortunato Gomez V CAYsa CatNessuna valutazione finora

- #Fressel V Mariano UyDocumento1 pagina#Fressel V Mariano UyKareen BaucanNessuna valutazione finora

- Arra Realty Corporation vs. Guarantee Development Corporation and Insurance Agency, 438 SCRA 441, September 20, 2004Documento33 pagineArra Realty Corporation vs. Guarantee Development Corporation and Insurance Agency, 438 SCRA 441, September 20, 2004EMELYNessuna valutazione finora

- Peoples Bank Vs OdomDocumento1 paginaPeoples Bank Vs Odomcmv mendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fressel v. Mariano Uy Chaco DigestDocumento2 pagineFressel v. Mariano Uy Chaco DigestIreneNessuna valutazione finora

- Technogas vs. CA - Accession Continua Builder in Bad FaithDocumento3 pagineTechnogas vs. CA - Accession Continua Builder in Bad Faithjed_sinda100% (1)

- 15 Fressel v. Marianno Uy Chaco CoDocumento4 pagine15 Fressel v. Marianno Uy Chaco CoFarhan JumdainNessuna valutazione finora

- Agency - Independent Contractor - Paderna Francis StephenDocumento1 paginaAgency - Independent Contractor - Paderna Francis StephengongsilogNessuna valutazione finora

- Noland Company, Inc. v. Allied Contractors, Incorporated, and Maryland Casualty Company, 273 F.2d 917, 4th Cir. (1959)Documento5 pagineNoland Company, Inc. v. Allied Contractors, Incorporated, and Maryland Casualty Company, 273 F.2d 917, 4th Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Freiburg v. Dreyfus, 135 U.S. 478 (1890)Documento5 pagineFreiburg v. Dreyfus, 135 U.S. 478 (1890)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Humphrey v. Harrison Bros., Inc, 196 F.2d 630, 4th Cir. (1952)Documento9 pagineHumphrey v. Harrison Bros., Inc, 196 F.2d 630, 4th Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- T.S.I., Inc., Cross-Appellant v. Metric Constructors, Inc., Cross-Appellee, 817 F.2d 94, 11th Cir. (1987)Documento5 pagineT.S.I., Inc., Cross-Appellant v. Metric Constructors, Inc., Cross-Appellee, 817 F.2d 94, 11th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Mankin v. United States Ex Rel. Ludowici-Celadon Co., 215 U.S. 533 (1910)Documento5 pagineMankin v. United States Ex Rel. Ludowici-Celadon Co., 215 U.S. 533 (1910)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Beaumont and Tenney For Appellant. Bruce, Lawrence, Ross and Block For AppelleesDocumento10 pagineBeaumont and Tenney For Appellant. Bruce, Lawrence, Ross and Block For AppelleesConnieAllanaMacapagaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chan v. MacedaDocumento2 pagineChan v. MacedaRZ ZamoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Moyer v. United States, For Use of Trane Co., 206 F.2d 57, 4th Cir. (1953)Documento6 pagineMoyer v. United States, For Use of Trane Co., 206 F.2d 57, 4th Cir. (1953)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Nature of The CaseDocumento3 pagineNature of The CaseDylza Fia CaminoNessuna valutazione finora

- National Surety Co. v. Architectural Decorating Co., 226 U.S. 276 (1912)Documento6 pagineNational Surety Co. v. Architectural Decorating Co., 226 U.S. 276 (1912)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocumento7 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- AFP Retirement and Separation Benefits System (AFPRSBS) vs. SanvictoresDocumento28 pagineAFP Retirement and Separation Benefits System (AFPRSBS) vs. Sanvictores유니스Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1970 Cal App LEXIS 1814Documento7 pagine1970 Cal App LEXIS 1814Mark A. ButlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Paul Reiss Vs Jose MemijeDocumento3 paginePaul Reiss Vs Jose MemijeBreth1979Nessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocumento5 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- CaseDocumento61 pagineCaseTani AngubNessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocumento10 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- American Radiator & Standard Sanitary Corporation v. Maryland Casualty Company, 374 F.2d 839, 1st Cir. (1967)Documento4 pagineAmerican Radiator & Standard Sanitary Corporation v. Maryland Casualty Company, 374 F.2d 839, 1st Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. O'BRIEN, 220 U.S. 321 (1911)Documento4 pagineUnited States v. O'BRIEN, 220 U.S. 321 (1911)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- American Insurance Company v. First National Bank in St. Louis, 409 F.2d 1387, 1st Cir. (1969)Documento8 pagineAmerican Insurance Company v. First National Bank in St. Louis, 409 F.2d 1387, 1st Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Carlo Digest AtpDocumento5 pagineCarlo Digest AtpNatsu DragneelNessuna valutazione finora

- CONSOLACION Vs MaybankDocumento3 pagineCONSOLACION Vs MaybankssNessuna valutazione finora

- American Metals Service Export Co. v. Ahrens Aircraft, Inc., 666 F.2d 718, 1st Cir. (1981)Documento5 pagineAmerican Metals Service Export Co. v. Ahrens Aircraft, Inc., 666 F.2d 718, 1st Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Plaintiffs-Appellees Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Jose Valera y Calderon, Gibbs & GaleDocumento5 paginePlaintiffs-Appellees Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Jose Valera y Calderon, Gibbs & GaleKatrina BarrionNessuna valutazione finora

- Saint Paul Mercury Indemnity Company v. Wright Contracting Company, 250 F.2d 758, 4th Cir. (1958)Documento8 pagineSaint Paul Mercury Indemnity Company v. Wright Contracting Company, 250 F.2d 758, 4th Cir. (1958)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- UY CHICO Vs Union LifeDocumento2 pagineUY CHICO Vs Union LifeJacinto Jr JameroNessuna valutazione finora

- Zig Zag Spring Co. v. Comfort Spring Corp., 200 F.2d 901, 3rd Cir. (1953)Documento10 pagineZig Zag Spring Co. v. Comfort Spring Corp., 200 F.2d 901, 3rd Cir. (1953)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Quiroga V Parsons: Commission On Sales. However, According To The Defendant's Evidence, It Was Mariano LopezDocumento11 pagineQuiroga V Parsons: Commission On Sales. However, According To The Defendant's Evidence, It Was Mariano LopezKim EcarmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Uy Chico v. Union Life AssuranceDocumento2 pagineUy Chico v. Union Life AssuranceSab Amantillo BorromeoNessuna valutazione finora

- Obligations of VendeeDocumento14 pagineObligations of VendeeHuey CardeñoNessuna valutazione finora

- Guzman DIGESTDocumento5 pagineGuzman DIGESTCarmela SalazarNessuna valutazione finora

- Facts: 1. Technogas Phils. Manufacturing Corp. VS. CA 268 SCRA 5 DigestDocumento100 pagineFacts: 1. Technogas Phils. Manufacturing Corp. VS. CA 268 SCRA 5 DigestElbert TramsNessuna valutazione finora

- A. B. Cooley, D/b/a, Etc. v. Barten & Wood, Inc., 249 F.2d 912, 1st Cir. (1957)Documento4 pagineA. B. Cooley, D/b/a, Etc. v. Barten & Wood, Inc., 249 F.2d 912, 1st Cir. (1957)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- CIVREV-case DigestDocumento6 pagineCIVREV-case DigestseoNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 124049 June 30, 1999 RODOLFO P. VELASQUEZ, Petitioner, Court of Appeals, and Philippine Commercial International Bank, INC., RespondentDocumento4 pagineG.R. No. 124049 June 30, 1999 RODOLFO P. VELASQUEZ, Petitioner, Court of Appeals, and Philippine Commercial International Bank, INC., RespondentSam B. PinedaNessuna valutazione finora

- And The Statute of Frauds: Indebitatus AssumpsitDocumento19 pagineAnd The Statute of Frauds: Indebitatus AssumpsitEmailNessuna valutazione finora

- Objection To Ptfs Ex Parte M4Substitution of Party PlaintiffDocumento8 pagineObjection To Ptfs Ex Parte M4Substitution of Party PlaintiffzonelizzardNessuna valutazione finora

- Villa V Garcia BosqueDocumento6 pagineVilla V Garcia BosqueAbegail Protacio GuardianNessuna valutazione finora

- VILLAFLOR v. CA DigestDocumento3 pagineVILLAFLOR v. CA DigestPRINCESSLYNSEVILLANessuna valutazione finora

- Prop 3 - TSAI VS. CADocumento9 pagineProp 3 - TSAI VS. CABelle MaturanNessuna valutazione finora

- Saguisag V OchoaDocumento103 pagineSaguisag V Ochoabbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Crim Rev - RA 10630Documento15 pagineCrim Rev - RA 10630bbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Heirs of Malabanan V RPDocumento44 pagineHeirs of Malabanan V RPbbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nielson & Company V Lepanto Consolidated MiningDocumento22 pagineNielson & Company V Lepanto Consolidated Miningbbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chu Sr. V Benelda EstateDocumento8 pagineChu Sr. V Benelda Estatebbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lubos V GalupoDocumento5 pagineLubos V Galupobbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aldecoa & Co V Warner, Barnes & CoDocumento14 pagineAldecoa & Co V Warner, Barnes & Cobbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- City Government o Davao V Monteverde-ConsunjiDocumento9 pagineCity Government o Davao V Monteverde-Consunjibbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ong V CADocumento3 pagineOng V CAbbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bagaipo V CADocumento6 pagineBagaipo V CAbbbmmm123Nessuna valutazione finora

- 3/3 - V Semester Paper - I Civil Procedure Code (CPC) : Res JudicataDocumento63 pagine3/3 - V Semester Paper - I Civil Procedure Code (CPC) : Res JudicataEshwar Prasad ENessuna valutazione finora

- 18jo0031 - TitikDocumento2 pagine18jo0031 - TitikArchibald GenaviaNessuna valutazione finora

- Affidavit - Middle - Pag-IbigDocumento3 pagineAffidavit - Middle - Pag-IbiggiovanniNessuna valutazione finora

- Affidavit of Loss - Driver's License EchavezDocumento1 paginaAffidavit of Loss - Driver's License EchavezAhmad AbduljalilNessuna valutazione finora

- RULE 34 35r FullDocumento13 pagineRULE 34 35r FullTNVTRLNessuna valutazione finora

- Bill of RightsDocumento8 pagineBill of RightsGao DencioNessuna valutazione finora

- Sps Evangelista v. Mercator Finance Corp.Documento6 pagineSps Evangelista v. Mercator Finance Corp.janezahrenNessuna valutazione finora

- Search: Chanrobles On-Line Bar ReviewDocumento6 pagineSearch: Chanrobles On-Line Bar ReviewMarielNessuna valutazione finora

- Dominador Sobrevinas For Plaintiffs-Appellants. Muss S. Inquerto For Defendant-AppelleeDocumento5 pagineDominador Sobrevinas For Plaintiffs-Appellants. Muss S. Inquerto For Defendant-AppelleeShally Lao-unNessuna valutazione finora

- Performance of ContractsDocumento27 paginePerformance of ContractsAshu SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Board of Liquidators Vs ZuluetaDocumento9 pagineBoard of Liquidators Vs ZuluetaLouNessuna valutazione finora

- BLL15 - Holder in Due Course and Protection To Bankers, CrossingDocumento5 pagineBLL15 - Holder in Due Course and Protection To Bankers, Crossingsvm kishore100% (1)

- TRANSPO-2021-3RD-EXAM-JGW (JPL Notes)Documento11 pagineTRANSPO-2021-3RD-EXAM-JGW (JPL Notes)Jaya LapecirosNessuna valutazione finora

- 09 Raymundo Vs Suarez, GR No. 14017, 28 November 2008Documento12 pagine09 Raymundo Vs Suarez, GR No. 14017, 28 November 2008Angeli Pauline JimenezNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic v. Principalia ManagementDocumento8 pagineRepublic v. Principalia ManagementEzra RamajoNessuna valutazione finora

- DPCDocumento16 pagineDPCGunjan SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Silverio Sr. vs. Silverio Jr.Documento17 pagine1 Silverio Sr. vs. Silverio Jr.Elaine GuayNessuna valutazione finora

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondent: First DivisionDocumento12 paginePetitioner Vs Vs Respondent: First Divisionkumiko sakamotoNessuna valutazione finora