Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Lost in The Funhouse by John Barth

Caricato da

Anali Roxana Pacoticona MamaniDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Lost in The Funhouse by John Barth

Caricato da

Anali Roxana Pacoticona MamaniCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Lost in the Funhouse by John Barth

BACKGROUND

John Barth is best known for his wit and clever use of language. He wrote short stories like "Lost in the Funhouse," and novels like The Sot-Weed Factor and The Floating Opera. This story was published in 1968, a time of great upheaval in America (race riots, war, hippies, etc.). This story takes place on Independence Day during World War II. The layout of the story is weird. It looks like there are parts of the story out of order and math problems in the middle. They all are part of some equations or formula Barth wants you to put together. The crazy nature of the story makes the story a funhouse in itself.

MAIN CHARACTERS

Ambrose: The main dude of the story. He is at that awkward, thirteen-year-old time in his life. Magda: A fourteen-year-old girl who goes on the vacation with Ambroses family.

PLOT

Ambrose takes a trip with his family to Ocean City, Maryland. Ambrose's parents and uncle sit up front in the car and he sits in the back with Magda and his older brother Peter. During the car ride, they play games. The first game is sighting towers, the other game is cards. Then they arrive in Maryland. They go to the boardwalk and Ambrose's mom gives him money to go have fun. Ambrose is very nervous because he likes Magda. His older brother acts cool around Magda and Ambrose hates that. He wants to tell Magda that he loves her. Then the kids go in the funhouse. Peter and Magda go off by themselves, and Ambrose is left alone in the funhouse.

THINGS TO MAKE YOU LOOK SMART

The narrator of this story is aware that the story is written there are references made to grammar and language, and to the words being fiction. Barth uses the narrator to address issues of story writing he mentions several different ways the story could end. In the end, the fact that Ambrose is left all alone is very symbolic. The love of his life and his older brother ran off together to another part of the funhouse. Ambrose is left all alone, betrayed, in a hall of mirrors. Note that the story takes place on Independence Day and how Ambrose is learning about being his own person. The mirrors in the funhouse could be seen as fragments of Ambrose he is confronted with images of himself, with no way out. The crazy, wacky funhouse could symbolize how Ambrose has trouble finding his way out of his emotions now that Magda has gone off. The funhouse is a huge part of the story. Not only does it represent his love life, but also his awkward stage in life is like a funhouse: nothing makes sense. He is afraid in the funhouse, like he is afraid in life. The mathematical equations in this story suggest a couple of things: there are parts to Ambrose that he has to figure out, like how he feels and who is growing into. Also, the equations are parts of the storys structure. Barth deconstructs the actual writing of a short story while writing Ambroses story. "Lost in the Funhouse" is about the technique of building plot and characters and making things interesting without getting "lost." Barth was a master at analytical writing, but also knew the dangers of it -- sometimes, when you look too closely at things, or study your feelings too much, they dont make sense anymore. The last line of the story suggests that, for writers, or those who create rather than experience, there exists an emptiness Ambrose, and perhaps Barth, as an author, realized that he will be forever in the role of "constructing funhouses for others," never in the role as the lovers who are allowed inside.

Unsure, confused, frustrated, mind boggling, leaving one at a loss with words, because trying to decode the thoughts of an adolescent may seem next to the impossible. The adolescent's mind is like that of a funhouse, the same funhouse that is much like the one described in John Barth's short story, "Lost in the Funhouse." A funhouse is a likely place to lose all inhibitions, while gaining vulnerability with each tightening corridor. Although the funhouse in this story is actually that of an adolescent's mind we still see the parallel between the actual funhouse and the mind of an adolescent. The constant and endless distractions of mirrors, moving hallways, and hidden passageways turn into unruly thoughts of sex, embarrassment, and rejection. Standing idle in the darkness of the funhouse is similar to the stage of puberty; it is a labyrinth of emotions.

Alienation is easily felt by anyone who is going through this awkward stage of puberty in life, not to mention the most mundane objects turning into thoughts of erotic pleasures and sexual encounters. One can see these sudden lustful feelings through the eyes of the main character "Ambrose." Ambrose is beginning to build up his sexual energy by noticing "Magda's"-a young Lolita and not to mention sexual icon for all the males in the story-bra straps. Ambrose embraces the idea that this sultry young Lolita can peel a banana with her teeth while holding it in her left hand; almost a subtle indication of a teasing oral sex act. The constant mention and notice of Magda's welldeveloped body excites Ambrose, but it also creates a contradiction on Magda's behalf, given that she is embarrassed by her body. Magda is extremely insecure about her well-developed body-like many girls are at that age-she is embarrassed by the toll puberty has taken on her body. Like Ambrose, Magda too shares the emotional struggle of puberty and all of the quirks it brings to the body; from menstruating to random penile erections, from firsts loves to rejection. Puberty, in this aspect is the pivotal point of sexual awakening and self-discovery, where much like Ambrose and Magda, we want to let our guard down once we enter the mouth with big red lips that leads us into the heart of puberty. For both Ambrose and Magda they both wish that they have never entered the door to the funhouse, but they have. Puberty is an inescapable stage in life; it is the prerequisite into adulthood and the dying stage of the adolescent years. Every uncontrollable emotion becomes controlled, the funhouse becomes more structured and less impulsive with the thoughts of sex, the embarrassment fades into the passing corridors, and the rejection becomes a part of life's encounters with love and lusts.

The first thing John Barth asks the reader to do when opening the cover of the book that contains his story Lost in the Funhouse is cut out a little strip of paper on which the words Once upon a time appear on one side and There was a story that began on the other. If the reader follows Barths directions for connecting the opposite corners to each other, he will have made a Moebius strip, a continuous loop about stories about stories, a visual demonstration of the theory behind the stories in the collection. The title story is the centerpiece of the book. First published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1967, Lost in the Funhouse has become not just one of Barths most famous pieces, but one of the most critically acclaimed short stories of the latter half of the twentieth century. While some readers are baffled or put-off by Barths interrupting and selfconscious narrator, others have been dazzled by his virtuosity and humor. Most agree, however, that he succeeds in his declared intent to present old material in new ways. In the words of critic Charles Harris, Barths fiction reflects the grim if often comicat times nobledetermination to find new ways to express the old (which is to say fundamental, essential) significances.

Author Biography

John Simmons Barth was born on May, 27, 1930, to John Jacob and Georgia Barth in Cambridge, Maryland. After graduating from public high school in 1947, he enrolled in the prestigious Julliard School of music with dreams of becoming an arranger, or orchestrator. He soon shifted his interest, however, and enrolled in Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and began his lifelong involvement with literature and writing. By the time he had received his B.A. from Johns Hopkins in 1951, he was married and the father of a daughter. Barth continued at Johns Hopkins and received his M.A. in creative writing in 1952. After the birth of his second child, he was forced for financial reasons to discontinue his doctoral work and accept a teaching position at Pennsylvania State University. After his first novel, The Floating Opera, was nominated for the National Book Award, he was promoted to the rank of assistant professor. Three novels later, in 1960, he was promoted to associate professor. He moved to Buffalo to become professor of English at the State University of New York in 1965, was divorced in 1969, and remarried in 1970. Finally, in 1973, Barth returned to his Maryland roots and became a professor of English and creative writing at Johns Hopkins. In 1990 he retired with the rank of Professor Emeritus, but has remained an active and productive writer. His latest novel, The Tidewater Tales, was published in 1997. Three aspects of Barths life have shaped and colored his remarkable literary career. The first is his early and sustained interest in music. Although he discontinued his formal study at Julliard, Barth has remained fascinated with playing the role of the arranger in his fiction. The second aspect of his life reflected in his work is the landscape and history of his native Maryland where he has lived for nearly all of his life and where much of his fiction is set. Finally, Barths work is also informed by his long career in academia, where he was immersed in the influence of literary criticism and theory.

Plot Summary

On the surface, Lost in the Funhouse is the story of a thirteen-year-old boys trip to the beach with his family on the fourth of July during World War II. With Ambrose are his older brother Peter, their mother and father, their Uncle Karl, and a fourteen-yearold neighbor girl, Magda, to whom both Ambrose and Peter are attracted. Having learned that the beach is covered in oil and tar from the fleet off-shore, the group decides to go through the funhouse instead. Both boys fantasize about going through the maze with Magda, but it suddenly becomes clear to Ambrose that he has misunderstood the meaning of the funhouse, has failed to see that to get through expeditiously was not the point. He realizes that he is too young to understand or engage in the sexual play associated with the funhouses dark corners. More profoundly, however, he also realizes that he is constitutionally different from his bother and Magda: he is not the type of person for whom funhouses are fun. Confused and separated from the others, Ambrose takes a wrong turn and loses his way. During the process of finding his way out of the dark corridors and back hallways, he comes to some realizations about himself and about funhouses. Specifically, he understands that his crippling self-consciousness also comes with a gift, an extraordinary imagination. Recognizing that the artistic life brings alienation as well as satisfaction he resolves to construct funhouses for others and be their secret operatorthough he would rather be among the lovers for whom funhouses are constructed. Ambroses ill-fated visit to the funhouse, however, is only part of the story. A third person omniscient narrator, sometimes identified with Ambrose or with the author himself, constantly interrupts the story of Ambrose and his familys visit to the beach to comment on the storys own construction and to call the readers attention to the way literary devices make meaning. The story itself becomes a funhouse of language through which the reader must find his or her way, but the narrative intrusions also point out whats real and whats reflectionor more accurately, that everything is a reflectionand how the hidden levers work behind the scenes.

Characters

Ambrose

Ambrose is the main character in the story and serves as the authors alter ego, or other self. At thirteen, he is at that awkward age, and in addition to the usual adolescent gawkiness, he is exceptionally introspective and self-conscious. Ambrose is not only just becoming aware of his sexuality, he is experiencing the first inklings of his artistic temperament. In the narrators words, There was some simple, radical difference about him; he hoped it was genius, feared it was madness, devoted himself to amiability and inconspicuousness.

Father

That Ambroses father wears glasses and is a principal at a grade school is essentially all the description the story provides. Later in the story, the narrator describes the boys father as tall and thin, balding, fair-complexioned. At times he betrays a disgruntled nostalgia for the old days.

Fat May

Not technically a character, Fat May the Laughing Lady is a mechanical sign at the entrance to the funhouse whose laughter and bawdy gestures Ambrose feels are directed toward him.

Magda

At fourteen, Magda, a girl from the boys neighborhood, is very well developed for her age. When she goes through the funhouse with Ambroses older brother, Ambrose realizes how different he is from the lovers for whom the funhouse is fun. On an earlier occasion, she is the girl who provides Ambrose with his first (and unsatisfying) sexual experience as part of a game. She is the object of Ambroses desire, and he likes to imagine himself married to her someday.

Mother

Ambrose and Peters mother is a cheerful woman whom the narrator describes as pretty, but any additional details are withheld. She does not share Ambroses brooding qualities. In fact, she likes to tease her sons because of their attention to Magda.

Peter

Peter, Ambroses fifteen-year-old brother, possesses the physical grace and uncomplicated view of life that Ambrose lacks. Although Ambrose knows that his older brother is not as smart as he is (he wont be able to grasp the secret to being the first to spot the landmark Towers on the way to Ocean City, for example), he envies Peters ability to understand the purpose of the funhouse and to find his way through it.

Uncle Karl

Though the story never reveals whose brother Karl is, in physical appearance he is the fathers opposite. Both Peter and Karl have dark hair and eyes, short, husky statures, deep voices. He works as a masonry contractor and likes to tease the boys and their mother.

Themes

Sex

Just as the funhouse poses mirrors in front of mirrors, tempting the viewer to mistake image for substance, Lost in the Funhouse seduces readers into believing the familiar literary truism that sex is a metaphor for language. What Ambrose learns in his journey through the three dimensional funhouse in Ocean City and the narrative funhouse of the story is that the opposite is true: language is just a metaphor for sex. Sex, in fact, is the whole point . . . Of the entire funhouse! Everywhere Ambrose hears the sound of sex, The shluppish whisper, continuous as seawash round the globe, tidelike falls and rises with the circuit of dawn and dusk. He imagines if he had X-ray eyes he would see that all that normally showed, like restaurants and

Topics for Further Study

Although Barth abandoned his early formal study of music, he remains interested in it. In fact he said in an interview that as a writer he still thinks of himself as an arranger, a kind of re-orchestrator. What about Lost in the Funhouse strikes you as musical and why? Investigate the effects World War II had on the social and economic lives of Americans. How is the wartime setting significant to the story? What other characters from literature you have read remind you of Ambrose? How has Barth presented the old story in new ways? Barth has said that he believes that Lost in the Funhouse would lose part of [its] point in any except print form. Nevertheless, can you imagine a way that the story could be told on film, video, or the stage? What about a hypertext version for the computer?

dance halls and clothing and test-your strength machines was merely preparation

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Lost in The Funhouse-AnalysisDocumento2 pagineLost in The Funhouse-AnalysiscarlzhangNessuna valutazione finora

- Lost in The Funhouse (Life-Story)Documento6 pagineLost in The Funhouse (Life-Story)Carmen VoicuNessuna valutazione finora

- This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideDa EverandThis Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideNessuna valutazione finora

- Modernist Novel WoolfDocumento14 pagineModernist Novel WoolfSopco Stefana Madalina100% (1)

- 2 DramaDocumento7 pagine2 DramaJohn RajkumarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Lady With The Dog RevisionDocumento4 pagineThe Lady With The Dog RevisionToni Junior ObatusinNessuna valutazione finora

- Absalom, Absalom! Is Considered To Be One of Faulkner's Most Difficult Novels Because ofDocumento3 pagineAbsalom, Absalom! Is Considered To Be One of Faulkner's Most Difficult Novels Because ofGeanina PopescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Edgar Allan Poe Reviews HawthorneDocumento1 paginaEdgar Allan Poe Reviews HawthorneŞeyda BilginNessuna valutazione finora

- Anthem For Doomed YouthDocumento5 pagineAnthem For Doomed YouthMohsin IqbalNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Romanticism and The NovelDocumento2 pagine1 Romanticism and The NovelAronRouzautNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 5 - The Second Generation of Romantic Poetry - Kérchy - EFOPDocumento17 pagineUnit 5 - The Second Generation of Romantic Poetry - Kérchy - EFOPKamillaJuhászNessuna valutazione finora

- Characteristics of Romantic AgeDocumento2 pagineCharacteristics of Romantic AgeShamira Alam100% (2)

- Novel 1: - English Studies - S5P1 - Number of The Module (M27) - Professor: Mohamed RakiiDocumento9 pagineNovel 1: - English Studies - S5P1 - Number of The Module (M27) - Professor: Mohamed RakiiKai Kokoro100% (1)

- Choose 2 Questions For Each Play and Write The Answers in Your Study PortfolioDocumento9 pagineChoose 2 Questions For Each Play and Write The Answers in Your Study PortfolioMădălina GreensNessuna valutazione finora

- Mrs. DallowayDocumento5 pagineMrs. DallowayJorge SebastiánNessuna valutazione finora

- Mark On The Wall - Kanchana UgbabeDocumento27 pagineMark On The Wall - Kanchana UgbabePadma UgbabeNessuna valutazione finora

- Thackeray AnalysisDocumento2 pagineThackeray AnalysisChamplooist100% (3)

- A Painful CaseDocumento11 pagineA Painful CasekashishNessuna valutazione finora

- British Literature IDocumento3 pagineBritish Literature IAnil Pinto100% (1)

- British Literature StudiesDocumento16 pagineBritish Literature StudiesAlena KNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3: Reader-Response Criticism: A. B. C. DDocumento9 pagineUnit 3: Reader-Response Criticism: A. B. C. DMayMay Serpajuan-SablanNessuna valutazione finora

- Animal Farm EssayDocumento2 pagineAnimal Farm EssayNoah MobleyNessuna valutazione finora

- Sea of Poppies Postcolonial CritiqueDocumento8 pagineSea of Poppies Postcolonial CritiqueVineet MehtaNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of London School of Thought in LinguisticsDocumento2 pagineSummary of London School of Thought in LinguisticsAbdul Aziz0% (2)

- Precaution by Cooper, James Fenimore, 1789-1851Documento239 paginePrecaution by Cooper, James Fenimore, 1789-1851Gutenberg.orgNessuna valutazione finora

- Russian FormalismDocumento4 pagineRussian FormalismDiana_Martinov_694100% (1)

- Ideological State Apparatuses and Nationalism in OrwellDocumento2 pagineIdeological State Apparatuses and Nationalism in OrwellAnonymous k4ItB2BCm100% (1)

- The Castle of Otranto: Gothic LiteratureDocumento11 pagineThe Castle of Otranto: Gothic LiteratureJane CheungNessuna valutazione finora

- The French Lieutenant's WomanDocumento11 pagineThe French Lieutenant's Womancrynutza5367% (3)

- War Poetry in The WWIDocumento7 pagineWar Poetry in The WWINéstor Rosales100% (1)

- Edgar Allan PoeDocumento2 pagineEdgar Allan PoemarianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparison of HedgesDocumento17 pagineComparison of HedgesSu AlmNessuna valutazione finora

- The Waste LandDocumento2 pagineThe Waste LandemaNessuna valutazione finora

- The History of Tom Jones1Documento18 pagineThe History of Tom Jones1KATIE ANGELNessuna valutazione finora

- Comments of A Refusal To Mourn The Death, by Fire, of A Child in LondonDocumento11 pagineComments of A Refusal To Mourn The Death, by Fire, of A Child in Londonvirginiaus100% (2)

- English Literature. CursDocumento109 pagineEnglish Literature. CurspysyybNessuna valutazione finora

- Dream Song 14Documento9 pagineDream Song 14Elfren BulongNessuna valutazione finora

- Edward Fitzgerald and Sypnosis of His Rubaiyat of Omar KhayyamDocumento6 pagineEdward Fitzgerald and Sypnosis of His Rubaiyat of Omar KhayyamDaisy rahmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Daisy Miller NotesDocumento6 pagineDaisy Miller Notesirregularflowers100% (1)

- Alexander Pope - The Rape of The LockDocumento11 pagineAlexander Pope - The Rape of The LockHessa SulNessuna valutazione finora

- Victorian PoetryDocumento2 pagineVictorian PoetryOlivera BabicNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay On PrufrockDocumento13 pagineEssay On PrufrockGuillermo NarvaezNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes On Look Back in AngerDocumento9 pagineNotes On Look Back in AngerSuhani KhannaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Elizabethan AgeDocumento2 pagineThe Elizabethan AgeRuxandra OnofrasNessuna valutazione finora

- Naturalism InfoDocumento2 pagineNaturalism InfoMrs. PNessuna valutazione finora

- Oedipus RexDocumento12 pagineOedipus RexErold TarvinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Strange Meeting - Wilfred OwenDocumento2 pagineStrange Meeting - Wilfred OwenAarti Naidu100% (1)

- Assignment On English and American LiteratureDocumento12 pagineAssignment On English and American LiteratureChickie VuNessuna valutazione finora

- Tseliot and The WastelandDocumento9 pagineTseliot and The WastelandGalo2142Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fowles vs. DickensDocumento4 pagineFowles vs. Dickensboier_motocNessuna valutazione finora

- Modernism in American LiteratureDocumento7 pagineModernism in American LiteratureAbdurrahman Shaleh ReliubunNessuna valutazione finora

- Short StoryDocumento5 pagineShort Storyapi-376081909Nessuna valutazione finora

- Tess of The D'Urbervilles by Thomas HardyDocumento3 pagineTess of The D'Urbervilles by Thomas HardyDenisa Caragea100% (1)

- DR Faustaus As A Tragic HeroDocumento5 pagineDR Faustaus As A Tragic HeroSania Ahmad100% (1)

- M.A. 1 Semester - 2017 - Oroonoko 1: Oroonoko: Final Bit of NotesDocumento2 pagineM.A. 1 Semester - 2017 - Oroonoko 1: Oroonoko: Final Bit of NotesBasilDarlongDiengdohNessuna valutazione finora

- Modernism, PM, Feminism & IntertextualityDocumento8 pagineModernism, PM, Feminism & IntertextualityhashemfamilymemberNessuna valutazione finora

- I-Author's Life: "The Death of A Beautiful Woman Is Unquestionably The Most Poetical Topic in The World."Documento10 pagineI-Author's Life: "The Death of A Beautiful Woman Is Unquestionably The Most Poetical Topic in The World."Zyra Catherine MoralesNessuna valutazione finora

- Diaspora's Children A: Robert Murray DavisDocumento6 pagineDiaspora's Children A: Robert Murray DavisJaroslav ZelenýNessuna valutazione finora

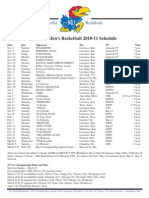

- 2010-2011 KU Basketball ScheduleDocumento1 pagina2010-2011 KU Basketball Scheduleahall423Nessuna valutazione finora

- English Y1 Guide Book KSSRDocumento47 pagineEnglish Y1 Guide Book KSSRsasauball100% (2)

- Adventures of A Wildlife Warden by E.R.C.Davidar PDFDocumento68 pagineAdventures of A Wildlife Warden by E.R.C.Davidar PDFravichan_2010Nessuna valutazione finora

- The WedgeDocumento7 pagineThe Wedgebanditgsk0% (1)

- RulesDocumento5 pagineRulesapi-348767429Nessuna valutazione finora

- FavreDocumento586 pagineFavreapi-305637690Nessuna valutazione finora

- Admin Installing SIS DVD 2011BDocumento3 pagineAdmin Installing SIS DVD 2011Bmahmod alrousan0% (1)

- Rochester Prep Lesson ScriptDocumento6 pagineRochester Prep Lesson ScriptRochester Democrat and ChronicleNessuna valutazione finora

- Carbon&Low-Alloy Steel Sheet and StripDocumento5 pagineCarbon&Low-Alloy Steel Sheet and Stripducthien_80Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Wyoming IncidentDocumento3 pagineThe Wyoming IncidentRachel McEnteeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Anthology of RapDocumento818 pagineThe Anthology of Rapteaguetodd100% (10)

- Index GGB MusicDocumento4 pagineIndex GGB MusicBuku ElectoneNessuna valutazione finora

- U.S. Marines in Battle An-NasiriyahDocumento52 pagineU.S. Marines in Battle An-NasiriyahBob Andrepont100% (1)

- Looxcie 3 User ManualDocumento4 pagineLooxcie 3 User ManualAndrewSchembriNessuna valutazione finora

- 31 Hardcore Work Out Finishers FinalDocumento24 pagine31 Hardcore Work Out Finishers FinalMaxim Borodin90% (10)

- Common Sense Media 2021Documento64 pagineCommon Sense Media 2021Alcione Ferreira SáNessuna valutazione finora

- Case 25 PDFDocumento19 pagineCase 25 PDFeffer scenteNessuna valutazione finora

- Who Wants To Be A Millionaire - Template by SlideLizardDocumento51 pagineWho Wants To Be A Millionaire - Template by SlideLizardThu Hà TrầnNessuna valutazione finora

- Hip Hop Abs & Turbojam Hybrid ScheduleDocumento1 paginaHip Hop Abs & Turbojam Hybrid ScheduleLou BourneNessuna valutazione finora

- t2 M 2460 Year 5 Calculate and Compare The Area of Rectangles Differentiated Activity Sheets - Ver - 7Documento12 paginet2 M 2460 Year 5 Calculate and Compare The Area of Rectangles Differentiated Activity Sheets - Ver - 7Melody KillaNessuna valutazione finora

- MUH 3211 PRE-Program Notes Assgn PDFDocumento2 pagineMUH 3211 PRE-Program Notes Assgn PDFChristopher William Paul WojahnNessuna valutazione finora

- Packet Tracer - Skills Integration Challenge: Addressing TableDocumento2 paginePacket Tracer - Skills Integration Challenge: Addressing TableTwiniNessuna valutazione finora

- DX225LCA Hydraulic Circuit 110705Documento1 paginaDX225LCA Hydraulic Circuit 110705carlosalazarsanchez_100% (6)

- Lista General Pae Planificacion de OperacionesDocumento4 pagineLista General Pae Planificacion de OperacionesFrank Carmelo Ramos QuispeNessuna valutazione finora

- Wheel Set: Dealer's ManualDocumento31 pagineWheel Set: Dealer's ManualHeather ColeNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic1 WorkbookDocumento73 pagineBasic1 WorkbookSamuel PonceNessuna valutazione finora

- Sách Economy TOEIC 3 - Phần NgheDocumento130 pagineSách Economy TOEIC 3 - Phần NgheAnh Túc VàngNessuna valutazione finora

- Honestly - Monsta X LyricsDocumento2 pagineHonestly - Monsta X LyricsMary Jane DumalaganNessuna valutazione finora

- SB Orders 01-01-2007Documento202 pagineSB Orders 01-01-2007Rajesh Mukundanaik KaggaNessuna valutazione finora

- James Baldwin - Sonny's Blues - Extract 1 - The Darkness OutsideDocumento1 paginaJames Baldwin - Sonny's Blues - Extract 1 - The Darkness OutsideErwan KergallNessuna valutazione finora

- An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960sDa EverandAn Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960sValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (3)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals Presents: Good Girl: Notes on Dog RescueDa EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals Presents: Good Girl: Notes on Dog RescueValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (31)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDa EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (32)

- Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesDa EverandSon of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (503)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsDa EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNessuna valutazione finora

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals Presents: Good Girl: Notes on Dog RescueDa EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals Presents: Good Girl: Notes on Dog RescueValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (4)

- Undefeated: Changing the Rules and Winning on My Own TermsDa EverandUndefeated: Changing the Rules and Winning on My Own TermsNessuna valutazione finora

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionDa EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (51)

- Liar's Poker: Rising Through the Wreckage on Wall StreetDa EverandLiar's Poker: Rising Through the Wreckage on Wall StreetValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1088)

- Say More: Lessons from Work, the White House, and the WorldDa EverandSay More: Lessons from Work, the White House, and the WorldNessuna valutazione finora

- George Müller: The Guardian of Bristol's OrphansDa EverandGeorge Müller: The Guardian of Bristol's OrphansValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (29)

- Autobiography of a Yogi (Unabridged)Da EverandAutobiography of a Yogi (Unabridged)Valutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (123)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndDa EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNessuna valutazione finora

- Hearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIDa EverandHearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (20)

- The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred RogersDa EverandThe Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred RogersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (359)