Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Out of Egypt Mt2 13-23

Caricato da

drla4Descrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Out of Egypt Mt2 13-23

Caricato da

drla4Copyright:

Formati disponibili

1st Sunday after Christmas 26 Dec 2010

Dr Lutz Ackermann (Christ Church, Polokwane)

Out of Egypt... (Mt 2: 13-23)

Out of the four gospel accounts, two start their narration with Jesus as a grown up man (Mark, John). Clearly, the public interest in Jesus started to arise, when Jesus was an adult. But it was only after his death and resurrection that people understood: this Jesus is special; and they started telling stories about him: about his teaching, about his life and of course about his death and resurrection. No-one would ever have been interested in stories about Jesus' birth unless they were convinced: this Jesus is very special. So, even though the other two gospel accounts (Luke, and Matthew) start with the birth of Jesus naturally, as any biography would we need to understand: Lk and Mt are writing of people, who have an interest in Jesus, in his life and teaching, his death and resurrection; and, yes, also in his birth. But that comes last, in the list of priorities. Why? Because here are readers, who are (potential) followers of Jesus, and they are adults; they want to follow an adult Jesus, are interested in primarily in Jesus adult life. And yet Matthew has decided to devote two chapters of his gospel to the birth and childhood stories [chapters?]. Why does he do that? Is it just the set-up for

the real thing? Let's give them some childhood stories so they are happy (and they have a reason to celebrate Christmas) before the actual gospel account begins... Well, I think the way Matthew tells the story of Jesus' birth shows that for him this is not just some kind of introduction to the actual thing, but it is already part of the main story, the gospel. He does it fairly briefly, not like Luke going into the family stories about Zechariah and Elisabeth and Jesus' cousin John first. No, Mt 1 starts with a long list of Jesus ancestors and then proceeds straight into the birth story by introducing Joseph and Mary as his parents (1:18). And the emphasis here is much more on Joseph: he is the one who hears from God in various dreams; he is the one, who names Jesus; he is the one who takes initiative to flee to Egypt, when things get a bit rough in Bethlehem; he is the one who takes his family back home, but then decides to move to Galilee (Nazareth). Is this just a collection of interesting stories to motivate, where this Jesus came from? If we listen carefully, we can discover a clue, why Matthew presents these stories. Three times in today's reading we heard the words: And so, what the prophet said, came true. Matthew doesn't just give us the story of Mary, Joseph and Jesus. He gives us the story of God. And it is a story of God and God's people. It is the story of God with Abraham, and with Moses; it is he story of God with David. Now Matthew is not just adding another story to all that. Like adding a chapter on Jesus. No, as he gives us his account, Matthew links it back to the previous stories. He can see, in the life of Jesus, a fulfilment of God's promises. For him, everything is design, everything has got a purpose (e.g. Bethlehem not like in Luke where Mary and Joseph are in B merely by historical accident at the time of Jesus birth). For Matthew all the details in his childhood story serve to illustrate, how in Jesus, God makes true God's promises. So we can ask: why does Matthew let the holy family flee to Egypt? Well, the connection is not all too difficult, if you know your bible, and especially the Old Testament. Because if you hear about Joseph, who receives dreams from God you may be reminded of another Joseph, who used to dream a lot; a Joseph, who in a biography of accidents could still see God's design; and a Joseph who ended up in Egypt.

But I believe, for Matthew the big figure which connects his story with the stories from the Hebrew scriptures is not so much Joseph, but Moses. Matthew tells us that all this happens to make what the Lord had said through the prophet come true, I called my Son out of Egypt. That is a quote from Hosea 1:11, and if we look at it in its original context, it refers to Israel. Israel is he one called out of Egypt, Israel is the one who is identified as God's Son. Now if we think about Israel and Egypt in the bible, it is all about the exodus. It is about how God delivers God's own people out of slavery. So, when Matthew presents Jesus as someone, who comes not only from Bethlehem (and Nazareth) but out of Egypt, he gives us more that just some geographic information; he tells us: here is someone, like Moses was. Here is someone, through whom God delivers God's people. That is the meaning of Jesus: God saves God's people. Like Moses only just escapes the killing of male Hebrews as a baby, so here in Matthew we see Jesus escaping the murderous attacks of King Herod. Like Moses went on a mountain to bring God's commandments, so a few chapters later Matthew has Jesus go on a mountain to deliver his famous sermon, which comes as God's new commandment. So the gospel account presents a parallel between the great figure of Moses on the one hand, the one through whom God has saved in the past; and between Jesus on the other hand, who is called out of Egypt to save God's people once again. Now, if you remember that Egypt is situated in the north of Africa, you can say: here is a Jesus, not only out of Egypt but out of Africa. This has often been forgotten or played own in our western traditions, but nowhere is it clearer than in Matthew 2:15. Jesus is a Saviour out of Africa; and Jesus is a saviour for Africa. He appears in Africa not only as an infant, but as a refugee. He suffers from political persecution and is brought across the borders by his parents to protect him from the atrocities of a despotic and blood-thirsty ruler. According to Josephus, a historian of biblical times, King Herod had many people killed, even members of his own family. So that is nothing new, and we see in this story Jesus in solidarity with those who are refugees.

We also see the holy family finding hospitality in Africa. This little episode about the flight to Egypt, I believe can tell us: then they needed a place to run to, hey found it on African soil. An so the Christmas narrative about the sweet little baby and his virgin mother all of a sudden becomes a political and a social story: about violence and persecution, about refugees and foreign countries. Out of Egypt I have called my Son. The story of Jesus becomes a second exodus. We live in a time, where Christmas, the celebration of the birth of Jesus, has become harmless and tame; it has become a sweet and moving story but so often an empty one. But the story of Christmas is not empty! It is not a story only of silent nights but of nights of hasty flight. Grab this, grab that and the child. We need to run away! It happens, where pain and suffering are not far away. But right here, in the middle of all the mess we are told: God is with us. And even: this happens by God's design. God is the one who can write a straight story, even on crooked lines. He is the one who wants to write the stories of our lives. And if we let him, it becomes a story of God with us, where things happen that make true God's promises.

Amen.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Faithful: Christmas Through the Eyes of JosephDa EverandFaithful: Christmas Through the Eyes of JosephValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- The First Christmas: What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus's BirthDa EverandThe First Christmas: What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus's BirthValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (58)

- Through the New Testament with Michael Green: Matthew to RevelationDa EverandThrough the New Testament with Michael Green: Matthew to RevelationNessuna valutazione finora

- He is Here!: 25 Days Of Christmas DevotionsDa EverandHe is Here!: 25 Days Of Christmas DevotionsNessuna valutazione finora

- The 2 Books of John: The Book of John The Essence of Jesus + The Book of Revelation As It IsDa EverandThe 2 Books of John: The Book of John The Essence of Jesus + The Book of Revelation As It IsNessuna valutazione finora

- Similarities and Differences Between The Infancy of Jesus According To The Gospel of Luke and MatthewDocumento4 pagineSimilarities and Differences Between The Infancy of Jesus According To The Gospel of Luke and MatthewaudsNessuna valutazione finora

- If You Are the Son of God: The Suffering and Temptations of JesusDa EverandIf You Are the Son of God: The Suffering and Temptations of JesusValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (4)

- Saints Insert May 20Documento3 pagineSaints Insert May 20MaryChallonerNessuna valutazione finora

- Where Do We Find Jesus in The Old TestamentDocumento17 pagineWhere Do We Find Jesus in The Old TestamentHoa Giấy Ba MàuNessuna valutazione finora

- Second Passion of the Christ-Three Days in Hell-ResurrectionDa EverandSecond Passion of the Christ-Three Days in Hell-ResurrectionNessuna valutazione finora

- Bible Understanding Made Easy (Vol 2): Volume 2: Matthew's GospelDa EverandBible Understanding Made Easy (Vol 2): Volume 2: Matthew's GospelNessuna valutazione finora

- Studying the Gospel of Mark: Exploring Christ, the Cross, and the Contemporary - Session 7Da EverandStudying the Gospel of Mark: Exploring Christ, the Cross, and the Contemporary - Session 7Nessuna valutazione finora

- Exploring the Word of God: Introduction to the GospelsDa EverandExploring the Word of God: Introduction to the GospelsNessuna valutazione finora

- Apocalypse of Magdalene & Judas: Everything Church Does Not Want You to KnowDa EverandApocalypse of Magdalene & Judas: Everything Church Does Not Want You to KnowValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Beyond Today -- the Lamb Foreordained Before the Foundation of the WorldDa EverandBeyond Today -- the Lamb Foreordained Before the Foundation of the WorldNessuna valutazione finora

- Hearts on Fire: The Joy of Celebrating the True EasterDa EverandHearts on Fire: The Joy of Celebrating the True EasterNessuna valutazione finora

- On the Road with Jesus: Birth and MinistryDa EverandOn the Road with Jesus: Birth and MinistryValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Bible Trivia for Kids (Play & Learn) | New Testament for Children Edition 1 | Children & Teens Christian BooksDa EverandBible Trivia for Kids (Play & Learn) | New Testament for Children Edition 1 | Children & Teens Christian BooksNessuna valutazione finora

- Alive in Me: The Word Is Alive in Me: Galatians 2:20 and Hebrews 4:12Da EverandAlive in Me: The Word Is Alive in Me: Galatians 2:20 and Hebrews 4:12Nessuna valutazione finora

- Jesus Now: Unveiling the Present-Day Ministry of ChristDa EverandJesus Now: Unveiling the Present-Day Ministry of ChristNessuna valutazione finora

- A Christmas Message From MatthewDocumento2 pagineA Christmas Message From MatthewDuan GonmeiNessuna valutazione finora

- A Story of Jesus' Life: Based on the Apocryphal GospelsDa EverandA Story of Jesus' Life: Based on the Apocryphal GospelsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Life and Death of Jesus within the Divine PlanDa EverandThe Life and Death of Jesus within the Divine PlanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Best of Will Willimon: Acting Up in Jesus' NameDa EverandThe Best of Will Willimon: Acting Up in Jesus' NameNessuna valutazione finora

- The Matthias Scroll: A Lost Testament Unearths the Secrets of History’S Most Notorious InjusticeDa EverandThe Matthias Scroll: A Lost Testament Unearths the Secrets of History’S Most Notorious InjusticeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Power of Parable: How Fiction by Jesus Became Fiction about JesusDa EverandThe Power of Parable: How Fiction by Jesus Became Fiction about JesusValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (27)

- The Jesus Chronicles: A Compilation of Volumes 1, 2 and 3Da EverandThe Jesus Chronicles: A Compilation of Volumes 1, 2 and 3Nessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Understanding The Infancy NarrativesDocumento22 pagine5 Understanding The Infancy NarrativesmargarettebeltranNessuna valutazione finora

- Christmas Vigil, Midnight, Dawn & Day - (B - 2006)Documento30 pagineChristmas Vigil, Midnight, Dawn & Day - (B - 2006)BerchmansNessuna valutazione finora

- The Advent of Jesus: A Devotional Celebrating the Coming Savior: Holiday Celebration Bible Study Series, #1Da EverandThe Advent of Jesus: A Devotional Celebrating the Coming Savior: Holiday Celebration Bible Study Series, #1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Word Pictures in the New Testament: Concise EditionDa EverandWord Pictures in the New Testament: Concise EditionValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (12)

- Te LucisDocumento1 paginaTe Lucisdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- An Unusual Ad Clerum!: The Diocese of ST Mark The EvangelistDocumento3 pagineAn Unusual Ad Clerum!: The Diocese of ST Mark The Evangelistdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Diocese of ST Mark The EvangelistDocumento2 pagineThe Diocese of ST Mark The Evangelistdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sunday HymsDocumento2 pagineSunday Hymsdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- At A Glance Guide To Locum Opportunities Revised December 2014Documento3 pagineAt A Glance Guide To Locum Opportunities Revised December 2014drla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mission Shaped Intro: Exploring Church For Those Who Do Not Do ChurchDocumento1 paginaMission Shaped Intro: Exploring Church For Those Who Do Not Do Churchdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rectors Year Plan - Release Jan 2018Documento1 paginaRectors Year Plan - Release Jan 2018drla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Website Poster InformationDocumento1 paginaWebsite Poster Informationdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gospel of Luke Session 1Documento4 pagineGospel of Luke Session 1drla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Locating Contextual Bible Study' Within Biblical Liberation Hermeneutics and Intercultural Biblical HermeneuticsDocumento21 pagineLocating Contextual Bible Study' Within Biblical Liberation Hermeneutics and Intercultural Biblical Hermeneuticsdrla4100% (1)

- ASFactsFinal Ilovepdf CompressedDocumento20 pagineASFactsFinal Ilovepdf Compresseddrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Diocese of ST Mark The Evangelist: 1 PersonalDocumento2 pagineThe Diocese of ST Mark The Evangelist: 1 Personaldrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Deutscher Evangelischer KirchentagDocumento7 pagineDeutscher Evangelischer Kirchentagdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Limp WRKSH PRGRM 15Documento4 pagineLimp WRKSH PRGRM 15drla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Graph Based MethodsDocumento3 pagineGraph Based Methodsdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Eric Symes Abbott Memorial Lecture 2007Documento13 pagineEric Symes Abbott Memorial Lecture 2007drla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Oid - Downloads - Eucharistic Prayer For Any OccasionDocumento2 pagineOid - Downloads - Eucharistic Prayer For Any Occasiondrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Altar BookDocumento30 pagineAltar Bookdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Real Enemy Is FundamentalismDocumento3 pagineReal Enemy Is Fundamentalismdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ad Laos On Primates MeetingDocumento3 pagineAd Laos On Primates Meetingdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Spiritual Gifts: Diocese of St. Mark The Evan GelistDocumento10 pagineSpiritual Gifts: Diocese of St. Mark The Evan Gelistdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mater Dei Pastoral Centre DirectionsDocumento1 paginaMater Dei Pastoral Centre Directionsdrla4Nessuna valutazione finora

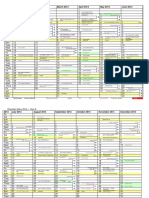

- 2014 January 2014 February 2014 March 2014 April 2014 May 2014 June 2014Documento3 pagine2014 January 2014 February 2014 March 2014 April 2014 May 2014 June 2014drla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Diocese of ST Mark The Evangelist Year Planning Notes For 2014Documento3 pagineDiocese of ST Mark The Evangelist Year Planning Notes For 2014drla4Nessuna valutazione finora

- Criteria For Authenticity, SteinDocumento25 pagineCriteria For Authenticity, Stein1abacabb_abacabb1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bible Quiz BeeDocumento3 pagineBible Quiz BeeCailo John UmpocNessuna valutazione finora

- Colossians CH 4 Bible StudyDocumento2 pagineColossians CH 4 Bible StudyPastor Jeanne100% (1)

- Gospel of MarkDocumento11 pagineGospel of Markandysibbz100% (1)

- Agnus Dei 6th December 2015 - Staff and Sol-FaDocumento5 pagineAgnus Dei 6th December 2015 - Staff and Sol-FaEoriwoh EdewedeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gospel of The Disciple Who Jesus LovedDocumento2 pagineThe Gospel of The Disciple Who Jesus LovedEricM14Nessuna valutazione finora

- Elective Assignment VivinDocumento4 pagineElective Assignment VivinVivin RodrhicsNessuna valutazione finora

- St. PeterDocumento13 pagineSt. PeterElla RodelladoNessuna valutazione finora

- 21 The Call of GodDocumento3 pagine21 The Call of GodJohn S. KodiyilNessuna valutazione finora

- Colossians PDFDocumento2 pagineColossians PDFRaymond0% (1)

- Mary Anoints Jesus FeetDocumento7 pagineMary Anoints Jesus Feetapi-3711938100% (1)

- The New Testament Writers Exhort, Encourage and Command Us To PrayDocumento2 pagineThe New Testament Writers Exhort, Encourage and Command Us To PrayGrace Church ModestoNessuna valutazione finora

- Sunday School Lesson Activity 516 Jesus Heals A Leper Mini BookDocumento12 pagineSunday School Lesson Activity 516 Jesus Heals A Leper Mini BookMihaela SzaszNessuna valutazione finora

- John The BelovedDocumento8 pagineJohn The BelovedGuinevere RaymundoNessuna valutazione finora

- 2021 New Testament Reading Plan - Aug Oct 2021Documento1 pagina2021 New Testament Reading Plan - Aug Oct 2021abrahamNessuna valutazione finora

- Discovery Series (Bible Study)Documento6 pagineDiscovery Series (Bible Study)Uwa OmoregbeeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Synoptic Problem: A HomeworkDocumento6 pagineThe Synoptic Problem: A HomeworkGinoSDBNessuna valutazione finora

- Independent Learning (3-21-2024) - PMDocumento15 pagineIndependent Learning (3-21-2024) - PMouia iooNessuna valutazione finora

- 03 Myers - GospelDocumento24 pagine03 Myers - GospelGabi CristianNessuna valutazione finora

- Contradictions of The GospelsDocumento3 pagineContradictions of The Gospels123kkscribdNessuna valutazione finora

- Over 300 Messianic Prophecies and Their FulfillmentDocumento23 pagineOver 300 Messianic Prophecies and Their FulfillmentCorneliusNessuna valutazione finora

- Keep Your Theological Train On Biblical TracksDocumento1 paginaKeep Your Theological Train On Biblical TracksChristopher SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- BIB 106 Course Outline September 2020Documento3 pagineBIB 106 Course Outline September 2020Philip KimawachiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Life of ChristDocumento3 pagineThe Life of ChristDaniel S. Santos0% (1)

- ChristologyDocumento195 pagineChristologyChristianHolly100% (2)

- 16 Proofs of A Pre-Trib RaptureDocumento3 pagine16 Proofs of A Pre-Trib RaptureTuan PuNessuna valutazione finora

- Young People in The Bible: Jairus' DaughterDocumento2 pagineYoung People in The Bible: Jairus' DaughterMyWonderStudio100% (3)

- The Last SupperDocumento2 pagineThe Last Supperwilfredo torresNessuna valutazione finora

- Sermon John 1 43-51 1 18 15Documento5 pagineSermon John 1 43-51 1 18 15api-318146278100% (1)

- The Parable of The TalentsDocumento3 pagineThe Parable of The TalentsEdmar Guingab ManaguelodNessuna valutazione finora