Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Obstruction of Justice Report

Caricato da

April Dream Mendoza PugonDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Obstruction of Justice Report

Caricato da

April Dream Mendoza PugonCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The term is used to refer to the acts punished under Presidential Decree No.

1829 (Penalizing Obstruction of Apprehension and Prosecution of Criminal Offenders). Full text here. What is the stated purpose of PD 1829? As stated in the law, its purpose is to discourage public indifference or apathy towards the apprehension and prosecution of criminal offenders, it is necessary to penalize acts which obstruct or frustrate or tend to obstruct or frustrate the successful apprehension and prosecution of criminal offenders. What is the penalty for Obstruction of Justice? The penalty is imprisonment, fine or both. Imprisonment ranges from 4 years, 2 months and 1 day to 6 years ( prision correccional in its maximum period). The fine ranges from P1,000 P6,000. Who may be charged under PD 1829? Any person whether private or public who commits the acts enumerated below may be charged with violating PD 1829. In case a public officer is found guilty, he shall also suffer perpetual disqualification from holding public office. What are the acts punishable under this law? The law covers the following acts of any person who knowingly or willfully obstructs, impedes, frustrates or delays the apprehension of suspects and the investigation and prosecution of criminal cases: a. Preventing witnesses from testifying in any criminal proceeding or from reporting the commission of any offense or the identity of any offender/s by means of bribery, misrepresentation, deceit, intimidation, force or threats. b. Altering, destroying, suppressing or concealing any paper, record, document, or object with intent to impair its verity, authenticity, legibility, availability, or admissibility as evidence in any investigation of or official proceedings in criminal cases, or to be used in the investigation of, or official proceedings in, criminal cases. c. Harboring or concealing, or facilitating the escape of, any person he knows, or has reasonable ground to believe or suspect, has committed any offense under existing penal laws in order to prevent his arrest, prosecution and conviction. d. Publicly using a fictitious name for the purpose of concealing a crime, evading prosecution or the execution of a judgment, or concealing his true name and other personal circumstances for the same purpose or purposes. e. Delaying the prosecution of criminal cases by obstructing the service of process or court orders or disturbing proceedings in the fiscals offices, in Tanodbayan, or in the courts. f. Making, presenting or using any record, document, paper or object with knowledge of its falsity and with intent to affect the course or outcome of the investigation of, or official proceedings in, criminal cases. g. Soliciting, accepting, or agreeing to accept any benefit in consideration of abstaining from, discontinuing, or impeding the prosecution of a criminal offender. h. Threatening directly or indirectly another with the infliction of any wrong upon his person, honor or property or that of any immediate member or members of his family in order to prevent a person from appearing in the investigation of, or official proceedings in, criminal cases, or imposing a condition, whether lawful or unlawful, in order to prevent a person from appear ing in the investigation of or in official proceedings in criminal cases. i. Giving of false or fabricated information to mislead or prevent the law enforcement agencies from apprehending the offender or from protecting the life or property of the victim; or fabricating information from the data gathered in confidence by investigating authorities for purposes of background information and not for publication and publishing or disseminating the same to mislead the investigator or the court. What are some of the instances when questions against charges under PD 1829 reached the Supreme Court? In Posadas vs. Ombudsman (G.R. No. 131492, 29 September 2000), certain officials of the University of the Philippines (UP) were charged for violating PD 1829 (paragraph c above). The UP officers objected to the warrantless arrest of certain students by the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI). According to the Supreme Court, the police had no ground for the warrantless arrest. The

UP Officers, therefore, had a right to prevent the arrest of the students at the time because their attempted arrest was illegal. The need to enforce the law cannot be justified by sacrificing constitutional rights. In another case, Sen. Juan Ponce Enrile was charged under PD 1829, for allegedly accommodating Col. Gregorio Honasan by giving him food and comfort on 1 December 1989 in his house. Knowing that Colonel Honasan is a fugitive from justice, Sen. Enrile allegedly did not do anything to have Honasan arrested or apprehended. The Supreme Court ruled that Sen. Enrile could not be separately charged under PD 1829, as this is absorbed in the charge of rebellion already filed against Sen. Enrile.

TO STRICTLY PENALIZE OFFENSES AGAINST THE PROPER ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE:

A CRITIQUE OF PRESIDENTIAL DECREE 1829 PENALIZING OBSTRUCTION OF APPREHENSION AND PROSECUTION OF CRIMINAL OFFENDERS

by Allan Verman Y. Ong

The things that will destroy us are: politics without principle; pleasure without conscience; wealth without work; knowledge without character; business without morality; science without humanity; and worship without sacrifice.[1] Mahatma Gandhi

Introduction: Tracing the Roots of the Crime of Obstruction of Justice

At an early date, the punishment of acts of obstructing the due administration of justice was recognized as absolutely essential to the existence of courts and their efficiency in performing the functions for which they were created. The great object for the existence of courts is the ascertainment of truth, and this can only be done fairly and impartially when all persons having knowledge of the transactions at issue are allowed to come before the courts for examination without hindrance from anyone. Thus, under American penal law, the obstruction of the administration of justice is an indictable offense under the common law, and by statute in most states.[2]

In the Philippines, Presidential Decree 1829 Penalizing Obstruction of Apprehension and Prosecution of Criminal Offenders was enacted into law on January 16, 1981. Upon its enactment, it was noted that crime and violence continue to proliferate despite the sustained vigorous efforts of the government to effectively contain them[3] and that there was a need to discourage public indifference or apathy towards the apprehension and prosecution of criminal offenders.[4] Therefore, it was necessary to penalize acts which obstruct or frustrate or tend to obstruct or frustrate the successful apprehension and prosecution of criminal offenders.[5] Despite the admirable purpose of the statute, which was to serve to bridge a huge gap in Criminal Law, there is a dearth of jurisprudence on PD 1829. The Supreme Court has only adjudicated four cases applying the law of PD 1829. This paper analyzes the law against obstruction of justice, presents a survey of the cases where the Supreme Court makes its pronouncements applying the law, and gives a critique of the law, theorizing why the Supreme Court seems to have been hesitant in the application thereof. American jurisprudence, which has developed a wealth of case law on this matter, will be used for its illustrative value, to supplement the lack of Philippine jurisprudence on the matter.

I. PD 1829: Penalizing Acts that Constitute Obstruction of Justice

The general meaning of obstruction of justice denotes an interference with the orderly administration of law, impeding or obstructing those who seek justice in court or those who have duties or power of administering justice therein.[6] PD 1829 penalizes any person who knowingly or willfully obstructs, impedes, frustrates or delays the apprehension of suspects and the investigation and prosecution of criminal cases by committing any of the following nine acts. These acts will be discussed separately on enumeration. Note that if any of the foregoing acts is committed by a public official or employee, he shall in addition to the penalties provided thereunder, suffer perpetual disqualification from holding public office.[7] (a) preventing witnesses from testifying in any criminal proceeding or from reporting the commission of any offense or the identity of any offender/s by means of bribery, misrepresentation, deceit, intimidation, force or threats;[8] Under this subsection, the act of obstructing the communication of information relating to the matters mentioned above is proscribed. The prohibition pertains to the use of means such as bribery, misrepresentation, intimidation, force, or threats of force. Thus, under American jurisprudence, it is illegal to cause a person to inform falsely, if the accused believes that an

official proceeding or investigation is pending or about to be instituted. A call to another requesting that he give false information to the police is not constitutionally-protected speech, and is punishable as obstruction of justice. Allegations that the defendant, intending to obstruct justice, unlawfully sought to induce others, in connection with an investigation, to mislead the investigation and not tell the investigators the true and complete facts support a conviction for obstruction of justice.[9] PD 1829 provides that if any of the acts mentioned in the law is penalized by any other law with a higher penalty, the higher penalty shall be imposed.[10] But this act does not seem to be penalized under Philippine penal law. The act of giving false testimony is penalized under the Revised Penal Code[11] as well as the act of refusing to answer.[12] But there is no other law which penalizes this same act. (b) altering, destroying, suppressing or concealing any paper, record, document, or object, with intent to impair its verity, authenticity, legibility, availability, or admissibility as evidence in any investigation of or official proceedings in, criminal cases, or to be used in the investigation of, or official proceedings in, criminal cases;[13] Under American jurisprudence, one who knowingly and willfully impedes a lawfully conducted police investigation of a crime by secreting, suppressing, or destroying evidence, knowing that it is being sought by investigating officers, may be prosecuted for the crime of obstruction of justice. Some states specifically make it a crime to destroy evidence with the intent to impair its availability as evidence in an investigation or official proceeding. Tampering with evidence pertains to the destruction or concealment of any book, paper, record, instrument of writing, or other matter or thing about to be produced in evidence and is not limited to written evidence but can extend to the destruction of contraband narcotics, as the term object encompasses an unending variety of physical objects.[14] (c) harboring or concealing, or facilitating the escape of, any person he knows, or has reasonable ground to believe or suspect, has committed any offense under existing penal laws in order to prevent his arrest prosecution and conviction;[15] The Revised Penal Code penalizes, as accessories, those who, having knowledge of the commission of the crime, and without having participated therein, either as principals or accomplices, take part, subsequent to its commission, by three acts: 1) profiting or to assisting the offender to profit by the effects of the crime, 2) concealing or destroying the body of the crime or the effects or instruments thereof, in order to prevent its discovery and 3) harboring, concealing or assisting in the escape of the principal of the crime, provided the accessory acts

with abuse of his public functions, or whenever the author of the crime is guilty of treason, parricide, murder, or an attempt to take the life of the Chief Executive, or is known to be habitually guilty of some other crime.[16] The third type of accessory is central to the analysis presented in this paper. Under the Revised Penal Code, there are two classes of accessories contemplated under the third type of accessory: 1. Public officers who harbor, conceal or assist in the escape of the principal of any crime (not light felony) with abuse of his public functions; and 2. Private persons who harbor, conceal or assist in the escape of the author of the crime guilty of treason, parricide, murder, or an attempt against the life of the President, or who is known to be habitually guilty of some other crime. [17] Thus, the Revised Penal Code does not penalize a person who harbors, conceals or assists in the escape of an author of a crime other than those specifically enumerated therein treason, parricide, murder, or an attempt on the life of the President. Various crimes such as kidnap for ransom, destructive arson, qualified rape, and crimes related to prohibited drugs, are of the same gravity[18] with the crimes listed under Art. 19 of the Code. But the Code does not penalize private persons who harbor, conceal or assist in the escape of the author of crimes such as kidnap for ransom. However, PD 1829 penalizes under the present subsection penalizes the act of harboring or concealing, or facilitating the escape of any person he knows or has reasonable ground to believe or suspect, has committed any offense under existing penal laws in order to prevent his arrest, prosecution and conviction. Here, there is no specification of the crime to be committed by the offender for criminal liability to be incurred for harboring, concealing, or facilitating the escape of the offender, and the offender need not be the principal unlike paragraph 3, Article 19 of the Revised Penal Code. Thus, although the subject acts may not bring about criminal liability under the Revised Penal Code, it may still be punishable under this particular subsection of PD 1829. Such an offender if violating Presidential Decree No. 1829 is no longer an accessory. He is simply an offender without regard to the crime committed by the person assisted to escape, and he is penalized as a principal. So in the problem, the standard of the Revised Penal Code, the person who helps the criminal escape is not criminally liable because crime is kidnapping, but under Presidential Decree No. 1829, the person who gives such aid is criminally liable.

Under paragraph 3, Article 19 of the Revised Penal Code, in the case of a civilian who harbors, conceals, or assists the escape of the principal, the RPC requires that the principal be found guilty of certain specified crimes. The paragraph uses the particular word guilty. So this means that before the civilian can be held liable as an accessory, the principal must first be found guilty of the crime charged, either treason, parricide, murder, or attempt to take the life of the Chief Executive. If the principal is acquitted, the civilian who harbored, concealed or assisted in the escape did not violate Art. 19 of the RPC. That is as far as the Revised Penal Code is concerned. But not Presidential Decree No. 1829. This special law does not require that there be prior conviction. It is a malum prohibitum, so there is no need for guilt, or knowledge of the crime. It is interesting to note that this particular act does not seem to be penalized under American jurisprudence on obstructing justice. (d) publicly using a fictitious name for the purpose of concealing a crime, evading prosecution or the execution of a judgment, or concealing his true name and other personal circumstances for the same purpose or purposes;[19] This particular act seems to be penalized also under the Revised Penal Code. Art. 178 penalizes the act of using fictitious names for purposes of concealing a crime, evading the execution of a judgment or causing damages. The same articles also penalizes any person who conceals his true name and other personal circumstances. The illegal use of a fictitious name under this article must be for the three said reasons, otherwise, if the damage concerns private interest, the offense may be punishable as estafa through the use of a fictitious name.[20] However, PD 1829 applies only where the person who knowingly or willfully obstructs, impedes, frustrates or delays the apprehension of suspects and the investigation and prosecution of criminal cases by committing any of the mentioned acts. Art. 178 which penalizes the use of fictitious name and the concealment of true name of a person to allow himself, not another person as provided in PD 1829, to conceal a crime, to evade the execution of a judgment or to cause damage. So PD 1829 and Art. 178 of the RPC do not seem to penalize the same offense. However, the wording of this particular subsection seems to imply that the acts must be done to evade a sentence on oneself. There is yet no case of the Supreme Court which clarifies this apparent duplicity. However, it is interesting to note that the penalty provided for in PD 1829 is prision correccional in its maximum period, or a fine ranging from 1,000 to 6,000 pesos, or both. In turn, the penalty provided for in Art. 178 is arresto mayor and a fine not to exceed 500 pesos. It thus appears that the penalty is more stringent in PD 1829. So should a person be penalized

under this subsection rather than Art. 178, the convicted person can be made to suffer a greater penalty. (e) delaying the prosecution of criminal cases by obstructing the service of process or court orders or disturbing proceedings in the fiscal's offices, in Tanodbayan, or in the courts;[21] American law on obstructing justice makes it a crime to obstruct the exercise of rights or performance of duties under federal court orders. Although certain acts that violate the statute may also constitute criminal contempt, the statute is designed to reach the actions of non-parties who are beyond the traditional reach of the contempt sanction. To support a conviction, there must be proof that the defendant had actual knowledge of the court order and intentionally obstructed justice. It is to be noted that a state court has noted that a person who obstructs an officer that is attempting to carry out a court decree may be convicted of obstructing the due course of justice, and not just of obstructing an officer in the execution of process, since the officer is acting in this situation as part of the judicial machinery.[22] The same observations apply to Philippine penal law. (f) making, presenting or using any record, document, paper or object with knowledge of its falsity and with intent to affect the course or outcome of the investigation of, or official proceedings in, criminal cases;[23] Furnishing false information includes withholding information or providing information that intentionally misleads. A misrepresentation statute applies to the concealment of true facts as well as to the assertion of what is false.[24] A suspect who gives a false identification to a police officer impedes the course of an investigation, and violates a statute dealing with obstruction of an officer in the discharge of his duty.[25] Under American jurisprudence, falsification of evidence with corrupt intent is an endeavor to obstruct justice. A state statute dealing with presentation of false documents for the purpose of misleading a public servant deals only with the use of false documents in court, not with the use of a genuine document as part of the support of a false alibi.[26] A false information statute may require that the information be given with the intent to prevent the prosecution and with knowledge that the information was untrue. This intent need not be proved by direct evidence but can be inferred from the surrounding circumstances. Three elements are required to convict one under a false reporting statute. There must be a false statement to a peace officer, it must be given with the intent to impede an investigation, and the investigation must be of an actual criminal matter.[27]

(g) soliciting, accepting, or agreeing to accept any benefit in consideration of abstaining from, discounting, or impeding the prosecution of a criminal offender;[28] This act seems to fall under the definition since the offense can only be committed by one who is responsible for the prosecution of a criminal offender, and on account of a benefit, abstains from, discounts or impedes the prosecution thereof. To wit, direct bribery is committed by any public officer who shall agree to perform an act constituting a crime, in connection with the performance of his official duties, in consideration of any offer, promise, gift or present received by such officer, personally or through the mediation of another.[29] This particular subsection of PD 1829 is similar to paragraph three of Art. 210 on Direct Bribery, which penalizes the public officer when the act of bribery constitutes the act of refraining from doing something which it was his official duty to do. The penalty to be imposed upon the public officer shall be prision correctional in its maximum period to prision mayor in its minimum period and a fine not less than three times the value of such gift.[30] In addition to this, Art. 210 imposes the penalty of special temporary disqualification. The provision shall apply to assessors, arbitrators, appraisal and claim commissioners, experts or any other person performing public duties.[31] Given that the act penalized in this subsection is similar to paragraph three of Art. 210, what shall be the penalty imposed? PD 1829 imposes the general penalty of prision correccional in its maximum period, or a fine ranging from 1,000 to 6,000 pesos, or both. This penalty is lighter than that given under Art. 210 on bribery. Therefore, the accused shall be imposed the penalty provided for under Art. 210, whether he is prosecuted under Art. 210 of the Revised Penal Code, or under PD 1829. (h) threatening directly or indirectly another with the infliction of any wrong upon his person, honor or property or that of any immediate member or members of his family in order to prevent such person from appearing in the investigation of, or official proceedings in, criminal cases, or imposing a condition, whether lawful or unlawful, in order to prevent a person from appearing in the investigation of or in official proceedings in, criminal cases;[32] Under American jurisprudence, it is made an offense by federal statute for one to influence, obstruct, or impede, or endeavor to influence, obstruct or impede, by means of threats of force or by any threatening letter or communication, the due and proper administration of the law under which any pending proceeding is being had before a federal department or agency.[33] Under PD 1829, the acts are punishable are likewise not limited to criminal investigations.

It has been indicated that the act must be calculated to obstruct the administration of the law to constitute a violation of the statute. However, the obstructionneed not be successful as one who endeavors to obstruct a proceeding may be convicted. There is also no requirement that the means used to obstruct justice beper se illegal.[34] This appears to be applicable as well under PD 1829, since this subsection does not require that the wrong inflicted on the person to prevent such person from appearing in an investigation or proceeding must constitute a crime. American jurisprudence likewise provides that although most instances when there was obstruction of justice have been based on acts of bribery, subornation of perjury, falsification of documents, threats, and the like, a corrupt attempt to influence a pending administrative proceeding may also include the use of legitimate arguments for concealed or falsified ends, such as asking an investigator for a favor that would benefit the target of an investigation, without disclosing that the request was made in return for a cash payment by the target.[35] This act is not punishable elsewhere in Philippine penal law and it is only PD 1829 which penalizes the said act. Art. 143 of the Revised Penal Code penalizes the commission of acts tending to prevent the meeting of Congress and similar bodies, but the criminal act contemplated in this subsection pertains to those participants who were supposed to aid in the investigation, and not the members of Congress themselves. (i) giving of false or fabricated information to mislead or prevent the law enforcement agencies from apprehending the offender or from protecting the life or property of the victim; or fabricating information from the data gathered in confidence by investigating authorities for purposes of background information and not for publication and publishing or disseminating the same to mislead the investigator or to the court.[36] The acts penalized under this subsection seems to be similar to those penalized under subsection (c) of the same PD 1829, since that subsection penalizes harboring or concealing, or facilitating the escape of, any person he knows, or has reasonable ground to believe or suspect, has committed any offense under existing penal laws in order to prevent his arrest prosecution and conviction.[37] Under American law on obstruction of justice, these such acts are penalized under other acts that constitute obstruction of justice. These include unlawfully obtaining and using unreleased grand jury transcripts and attempts to transmit or sell transcripts of secret grand jury testimony to persons under investigation, an agreement between co-defendants that one codefendant would absent himself as to cause a mistrial, persuading a co-defendant to absent himself from trial in order to improperly secure its postponement and such acts constitute the crime of obstruction of justice.[38]

However, it is not a crime under American jurisprudence to advice the recipient of a letter from a prosecutor not to comply with the prosecutors request to come to court and enter a plea, since the obstruction of justice statute should not be used to give to the attorneys notes or verbal requests the quality of process. And associating with a person whose conditions of probation forbid such association does not come within the meaning of the federal obstruction of justice statute.[39]

II. Jurisprudential Pronouncements on PD 1829: A Dearth of Pronouncements

Despite the admirable purpose of the statute and its interstitial nature which is to bridge certain gaps in the law, there has hardly been PD 1829 which have reached the Supreme Court. There are four cases reported where the accused was charged of PD 1829. These cases are as follows.

A. Enrile v. Amin

In the case of Juan Ponce Enrile v. Hon. Omar U. Amin,[40] Senator Juan Ponce Enrile was charged with rebellion complexed with murder in the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City for activities connected with the December 1989 coup d etat, and he was charged to be a coconspirator of Ex. Lt. Col. Gregorio Gringo Honasan. Government prosecutors filed another information charging him for violation of Presidential Decree No. 1829 with the Regional Trial Court of Makati. The information charged Enrile for willfully and knowingly obstructing, impeding, frustrating or delaying the apprehension of Honasan by harboring or concealing him in his house. Petitioner Enrile claimed that the pending charge of rebellion complexed with murder and frustrated murder against Senator Enrile as alleged co-conspirator of Col. Honasan, on the basis of their alleged meeting on December 1, 1989 precluded the prosecution of the Senator for harboring or concealing the Colonel on the same occasion under PD 1829. Both the RTC and the CA denied him relief on this ground and he filed a petition for certiorari with the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court invoked its ruling in the case of People v. Hernandez[41] where the Court laid down the doctrine operating to prohibit the complexing of rebellion with any other offense committed on the occasion thereof, either as a means necessary to its commission or as an unintended effect of an activity that constitutes rebellion. The Court observed:

This doctrine is applicable in the case at bar. If a person can not be charged with the complete crime of rebellion for the greater penalty to be applied, neither can he be charged separately for two (2) different offenses where one is a constitutive or component element or committed in furtherance of rebellion. xxxxxxxxx The prosecution in this Makati case alleges that the petitioner entertained and accommodated Col. Honasan by giving him food and comfort on December 1, 1989 in his house. Knowing that Colonel Honasan is a fugitive from justice, Sen. Enrile allegedly did not do anything to have Honasan arrested or apprehended. And because of such failure the petitioner prevented Col. Honasan's arrest and conviction in violation of Section 1 (c) of PD No. 1829. xxxxxxxxx x x x [T]he factual allegations supporting the rebellion charge constitute or include the very incident which gave rise to the charge of the violation under Presidential Decree No. 1829. Under the Department of Justice resolution there is only one crime of rebellion complexed with murder and multiple frustrated murder but there could be 101 separate and independent prosecutions for "harboring and concealing ' Honasan and 100 other armed rebels under PD No. 1829. The splitting of component elements is readily apparent.[42] Thus, the Supreme Court granted the petition and quashed the information. The Court held that since petitioner is now facing charges of rebellion in conspiracy with the fugitive Col. Gringo Honasan, being in conspiracy with Honasan, petitioner's alleged act of harboring or concealing was for no other purpose but in furtherance of the crime of rebellion thus constituting a component thereof. It was motivated by the single intent or resolution to commit the crime of rebellion. The crime of rebellion consists of many acts it is described as a vast movement of men and a complex net of intrigues and plots and jurisprudence tells us that acts committed in furtherance of the rebellion though crimes in themselves are deemed absorbed in the one single crime of rebellion. In this case, the act of harboring or concealing Col. Honasan is clearly a mere component or ingredient of rebellion or an act done in furtherance of the rebellion. It cannot therefore be made the basis of a separate charge.

The Court noted the prosecutions theory that harboring or concealing a fugitive is punishable under a special law while the rebellion case is based on the Revised Penal Code; hence, prosecution under one law will not bar a prosecution under the other. This argument is specious in rebellion cases. All crimes, whether punishable under a special law or general law, which are mere components or ingredients, or committed in furtherance thereof, become absorbed in the crime of rebellion and cannot be isolated and charged as separate crimes in themselves. Clearly, the petitioner's alleged act of harboring or concealing which was based on his acts of conspiring with Honasan was committed in connection with or in furtherance of rebellion and must now be deemed as absorbed by, merged in, and identified with the crime of rebellion punished in Articles 134 and 135 of the RPC.

B. People v. Elias Lovedioro

In the case of People v. Elias Lovedioro,[43] an off-duty policeman was walking when a man suddenly walked beside him fired a gun at the policeman's right ear and killed the policeman. The man who shot Lucilo had three other companions with him, one of whom shot the fallen policeman four times as he lay on the ground. After taking the latter's gun, the man and his companions boarded a tricycle and fled. A witness identified the man who fired at the deceased as Elias Lovedioro y Castro. Elias Lovedioro y Castro was charged and convicted in the Regional Trial Court for the crime of Murder under Article 248 of the Revised Penal Code. Appellant claims that the lower court erred in holding him liable for murder and not rebellion. He claims that Armenta, a police informer, identified him as a member of the New People's Army. Additionally, he contends that because the killing of Lucilo was "a means to or in furtherance of subversive ends," should have been deemed absorbed in the crime of rebellion under Arts. 134 and 135 of the Revised Penal Code. Finally, claiming that he did not fire the fatal shot but merely acted as look-out in the liquidation of Lucilo, he avers that he should have been charged merely as a participant in the commission of the crime of rebellion under paragraph 2 of Article 135 of the Revised Penal Code and should therefore have been meted only the penalty of prision mayor by the lower court. The Solicitor General in turn avers that the crime committed by appellant may be considered as rebellion only if the defense itself had conclusively proven that the motive or intent for the killing of the policeman was for "political and subversive ends." The Supreme Court held that the gravamen of the crime of rebellion is an armed public uprising against the government. By its very nature, rebellion is essentially a crime of masses or

multitudes involving crowd action, which cannot be confined a priori within predetermined bounds. One aspect noteworthy in the commission of rebellion is that other acts committed in its pursuance are, by law, absorbed in the crime itself because they acquire a political character. This peculiarity was underscored in the case of People v. Hernandez,[44] thus: In short, political crimes are those directly aimed against the political order, as well as such common crimes as may be committed to achieve a political purpose. The decisive factor is the intent or motive. If a crime usually regarded as common, like homicide, is perpetrated for the purpose of removing from the allegiance to the Government the territory of the Philippine Islands or any part thereof, then it becomes stripped of its "common" complexion, inasmuch as, being part and parcel of the crime of rebellion, the former acquires the political character of the latter. Divested of its common complexion therefore, any ordinary act, however grave, assumes a different color by being absorbed in the crime of rebellion, which carries a lighter penalty than the crime of murder. In deciding if the crime committed is rebellion, not murder, it becomes imperative for our courts to ascertain whether or not the act was done in furtherance of a political end. The political motive of the act should be conclusively demonstrated. In such cases, the burden of demonstrating political motive falls on the defense, motive, being a state of mind which the accused, better than any individual, knows. Clearly, political motive should be established before a person charged with a common crime-alleging rebellion in order to lessen the possible imposable penalty-could benefit from the law's relatively benign attitude towards political crimes. The Court said that the ruling in Enrile v. Amin[45] was instructive in this regard. The Supreme Court observed and ruled: x x x This Court held, against the prosecution's contention, that rebellion and violation of P.D. 1829 could be tried separately 14 (on the principle that rebellion is based on the Revised Penal Code while P.D. 1829 is a special law), that the act for which the senator was being charged, though punishable under a special law, was absorbed in the crime of rebellion being motivated by, and related to the acts for which he was charged in Enrile vs. Salazar (G.R. Nos. 92163 and 92164) a case decided on June 5, 1990. Ruling in favor of Senator Enrile and holding that the prosecution for violation of P.D. No. 1829 cannot prosper because a separate prosecution for rebellion had already been filed and in fact decided, the Court said:

The attendant circumstances in the instant case, however constrain us to rule that the theory of absorption in rebellion cases must not confine itself to common crimes but also to offenses under special laws which are perpetrated in furtherance of the political offense. [I]intent or motive is a decisive factor. If Senator Ponce Enrile is not charged with rebellion and he harbored or concealed Colonel Honasan simply because the latter is a friend and former associate, the motive for the act is completely different. But if the act is committed with political or social motives, that is in furtherance of rebellion, then it should be deemed to form part of the crime of rebellion instead of being punished separately. It follows, therefore, that if no political motive is established and proved, the accused should be convicted of the common crime and not of rebellion. In cases of rebellion, motive relates to the act, and mere membership in an organization dedicated to the furtherance of rebellion would not, by and of itself, suffice. The burden of proof that the act committed was impelled by a political motive lies on the accused. Political motive must be alleged in the information. It must be established by clear and satisfactory evidence.

C. People v. Medina and Carlos

PD 1829 was applied only tangentially in the case of People v. Medina and Carlos. [46] In this case, Jaime B. Medina and accused Virgilio Carlos were apprehended by members of the Narcotics Intelligence and Suppression Unit (NISU) under the Philippine National Police Narcotics Command (PNP-NARCOM) for selling Methamphetamine hydrochloride without authority of law. The two were brought before Assistant City Prosecutor Lillian H. Ramiro for inquest. Carlos denied any involvement in the transaction by claiming that he merely accompanied appellant to the place of the sale, while Medina stated that he was only supposed to buy the regulated drug at the agreed price of P250,000.00 when the policemen arrived and arrested them. Appellant added that, at his request, Carlos merely drove the car used by them. They were however charged in an Information where they were alleged to have conspired and confederated together and mutually helped each other, not having been authorized by law to sell, dispense, deliver, transport or distribute any regulated drug, did then and there wilfully and unlawfully sell or offer for sale 306.71 grams of methamphetamine hydrochloride, which is a regulated drug.

The court below rendered judgment holding that appellant conspired with accused Carlos in the illegal sale of 306.71 grams of shabu. As the trial court appreciated the presence of craft, fraud or disguise as aggravating circumstances against herein appellant, he was sentenced to suffer the supreme penalty of death. In the same decision, an alias warrant of arrest was issued by the court for the arrest of accused Virgilio Carlos. Medina sought the reversal of the ruling, saying that the lower court erred in finding a conspiracy between him and Virgilio Carlos. The Supreme Court upheld the ruling of the trial court. It held that in the case at bar, appellant was not merely present in a passive manner at the scene of the crime as he contends. He definitely took an active participation in the sale of the shabu. He was positively identified as the driver of the car carrying accused Carlos and the regulated drugs. When the duo arrived at the agreed place, appellant went down to check if the buyer brought the money while Carlos waited inside the car. Then, upon learning that the poseur-buyer had the money, appellant signaled to his companion indicating such fact. No other conclusion could follow from appellant's actions except that he had a prior understanding and community of interest with Carlos. His preceding inquiry about the money and the succeeding signal to communicate its availability reveal a standing agreement between appellant and his co-accused under which it was the role of appellant to verify such fact from the supposed buyer before Carlos would hand over the shabu. Without such participation of appellant, the sale could not have gone through as Carlos could have withdrawn from the deal had he not received that signal from appellant. It is undeniable, therefore, that appellant and his co-accused acted in unison and, moreover, that appellant knew the true purpose of Carlos in going to the restaurant. But the lower court considered the ruling sentencing the appellant to death due to its appreciation of the aggravating circumstances of craft, fraud or disguise. The Supreme Court found that a comprehensive search in the records of this case do not reveal these circumstances: The reason for this can be found in the very rationale adopted by the lower court in appreciating the said circumstances against appellant in the dispositive portion of its decision. The court stated that craft, fraud or disguise led to the escape and nonarrest of Virgilio Carlos, hence it apparently imputes the same to appellant. While we share the trial court's disgust over the still unexplained escape of accused Carlos, we cannot approve its attribution to herein appellant as the author of such craft, fraud or disguise or even that the same should aggravate his liability in the present case. For, even assuming ex gratia argumenti that appellant

had a part in the release of Carlos, it is obvious that the aggravating circumstances involved do not pertain to the offense charged in the information and are completely unrelated to the crime of illegal sale of shabu. The court a quo should have borne in mind that the charge against appellant is for illegal sale of shabu and not for obstructing the apprehension and prosecution of a criminal offender or, for that matter, perjury. In fact, if such circumstances in themselves constitute punishable crimes, or are included by the law in defining a crime and prescribing the penalty therefor, they cannot be considered as aggravating circumstances. To be considered as an aggravating circumstance and thereby resultantly increase the criminal liability of an offender, the same must accompany and be an integral part or concomitant of the commission of the crime specified in the information; and although it is not necessarily an element thereof, it must not be factually and legally discrete therefrom. Besides, it is highly problematical whether the Spanish legal concept of astucia, fraude and disfraz, adopted in our Revised Penal Code, can find application at all to the dismissal of the case against Carlos.[47] In view of the foregoing, the Supreme Court held that the lower court erred in considering against herein appellant the supposed aggravating circumstances of craft, fraud or disguise. The violation of Section 15 subject of the amended indictment was consequently committed without any aggravating circumstance. The Supreme Court here verified that acts punishable under Presidential Decree No. 1829 cannot be construed or constituted as mere aggravating circumstances, if indeed they were present in the case. They are penalized under the law as liable under PD 1829 and they must be made liable as such.

D. Soller v. Sandiganbayan

The most recent case applying PD 1829 is Prudente D. Soller v. Sandiganbayan and People.[48] This was a case for certiorari, prohibition and mandamusraising the issue of the propriety of the assumption of jurisdiction by the Sandiganbayan in Criminal Cases entitled People of the Philippines vs. Prudente D. Soller, Preciosa M. Soller, Rodolfo Salcedo, Josefina Morada, Mario Matining and Rommel Luarca wherein petitioners are charged with Obstruction

of Apprehension and Prosecution of Criminal Offenders as defined and penalized under P.D. No. 1829. It appears that in the evening of March 14, 1997, Jerry Macabael a municipal guard, was shot and killed along the national highway at Bansud, Oriental Mindoro while driving a motorcycle together with petitioner Sollers son, Vincent M. Soller. His body was brought to a medical clinic located in the house of petitioner Dr. Prudente Soller, the Municipal Mayor, and his wife Dr. Preciosa Soller, who is the Municipal Health Officer. An autopsy was conducted on the same night on the cadaver by petitioner Dr. Preciosa Soller with the assistance of petitioner Rodolfo Salcedo, Sanitary Inspector, and petitioner Josefina Morada, Rural Health Midwife. A complaint was later filed against the petitioners by the widow of Jerry Macabael with the Office of the Ombudsman charging them with conspiracy to mislead the investigation of the fatal shootout of Jerry Macabael by: (a) altering his wound ; (b) concealing his brain; (c) falsely stating in police report that he had several gunshot wounds when in truth he had only one; and (d) falsely stating in an autopsy report that there was no blackening around his wound when in truth there was. Petitioners Soller denied having tampered with the cadaver of Jerry Macabael, and claimed, among others that Jerry Macabael was brought to their private medical clinic because it was there where he was rushed by his companions after the shooting, that petitioner Prudente Soller, who is also a doctor, was merely requested by his wife Preciosa Soller, who was the Municipal Health Officer, to assist in the autopsy considering that the procedure involved sawing which required male strength, and that Mrs. Macabaels consent was obtained before the autopsy. But two Information were indeed filed with the Sandiganbayan charging the petitioners for criminally alter and suppress the gunshot wound and conceal the brain of Jerry Macabael with intent to impair its veracity, authenticity, and availability as evidence in the investigation of criminal case for murder against the accused Vincent Soller, the son of herein respondents. Petitioners filed a Motion to Quash on the principal ground that the Sandiganbayan had no jurisdiction over the offenses charged. The Sandiganbayan denied petitioners Motion to Quash on the ground that the accusation involves the performance of the duties of at least one of the accused public officials, and if the Mayor is indeed properly charged together with that official, then the Sandiganbayan has jurisdiction over the entire case and over all the co-accused.

The Supreme Court found the petition meritorious. The court held that the rule is that in order to ascertain whether a court has jurisdiction or not, the provisions of the law should be inquired into. Furthermore, the jurisdiction of the court must appear clearly from the statute law or it will not be held to exist. It cannot be presumed or implied. For this purpose in criminal cases, the jurisdiction of the court is determined by the law at the time of the commencement of the action. The Court found: The action here was instituted with the filing of the Informations on May 25, 1999 charging the petitioners with the offense of Obstruction of Apprehension and Prosecution of Criminal Offenders as defined and penalized under Section 1, Paragraph b of P.D.1829. xxxxxxxxx In cases where none of the accused are occupying positions corresponding to salary Grade 27 or higher, as prescribed in the said Republic Act 6758, or military and PNP officers mentioned above, exclusive original jurisdiction thereof shall be vested in the proper regional trial court, metropolitan trial court, municipal trial court, and municipal circuit trial court, as the case may be, pursuant to their jurisdictions as provided by Batas Pambansa Blg. 129, amended. The Supreme Court observed that the bone of contention here is whether the offenses charged may be considered as committed in relation to their office as this phrase is employed in Section 4 of PD 1892. As early as Montilla vs. Hilario,[49] the Supreme Court interpreted the requirement that an offense be committed in relation to the office to mean that the offense cannot exist without the office or that the office must be a constituent element of the crime.[50] People vs. Montejo[51]enunciated the principle that the offense must be intimately connected with the office of the offender and perpetrated while he was in the performance, though improper or irregular of his official functions. In this case, the Informations subject of Criminal Cases Nos. 25521 and 25522 quoted earlier, fail to allege that petitioners had committed the offenses charged in relation to their offices. Neither are there specific allegations of facts to show the intimate relation/connection between the commission of the offense charged and the discharge of official functions of the offenders, i.e. that the obstruction of and apprehension and prosecution of criminal offenders was committed in relation to the office of petitioner Prudente Soller, whose office as Mayor is

included in the enumeration in Section 4 (a) of P.D. 1606 as amended. Although the petitioners were described as being all public officers, then being the Municipal Mayor, Municipal Health Officer, SPO II, PO I, Sanitary Inspector and Midwife, there was no allegation that the offense of altering and suppressing the gunshot wound of the victim with intent to impair the veracity, authenticity and availability as evidence in the investigation of the criminal case for murder (Criminal Case No. 25521) or of giving false and fabricated information in the autopsy report and police report to mislead the law enforcement agency and prevent the apprehension of the offender (Criminal Case No. 25522) was done in the performance of official function. Indeed the offenses defined in P.D. 1892 may be committed by any person whether a public officer or a private citizen, and accordingly public office is not an element of the offense. Moreover, the Information in Criminal Case No. 25522 states that the fabrication of information in the police and autopsy report would indicate that the victim was shot by Vincent Soller, the son of herein petitioners spouses Prudente and Preciosa Soller. Thus there is a categorical indication that the petitioners spouses Soller had a personal motive to commit the offenses and they would have committed the offenses charged even if they did not respectively hold the position of Municipal Mayor or Municipal Health Officer. Consequently, for failure to show in the informations that the charges were intimately connected with the discharge of the official functions of accused Mayor Soller, the offenses charged in the subject criminal cases fall within the exclusive original function of the Regional Trial Court, not the Sandiganbayan. So the petition was granted and the orders were set aside for being void for lack of jurisdiction.

III. Analyzing the Seeming Non-Use of the Law

PD 1829s purposes are admirable and the acts they penalize should truly be proscribed in order for the efforts of law enforcers to bear fruit. Persons who obstruct the acts of administration of justice do not harm society as much as the acts of the criminal who is sought to be brought to justice. Nevertheless, it is necessary for there to be a meaningful exercise of law enforcement, for citizens not to hamper the acts of law enforcers. The provision of PD 1829 which has been used in the cases has been that in subsection (c) of Section 1 of the law which penalizes the act of harboring, concealing, or facilitating the escape of, any person he knows, or has reasonable ground to believe or suspect, has committed any offense under existing penal laws in order to prevent his arrest prosecution and conviction. But the cases surveyed reveal that there has hardly been any conviction even under

this act of obstructing justice, even as it appears to be the most commonly committed ground. There can be two reasons for the seeming non-use of this provision of the law. The first is that the criminals who are themselves in conspiracy with each other do not obtain aid from those who are not in conspiracy with them. Thus, they do not need third persons who have not participated in the crime to aid them in their escape. The second is that the cultural norms that move Philippine society has made it common, or even accepted, that relatives will harbor, conceal or facilitate the escape of other relatives who have committed crimes, regardless of the criminal nature of the act, because of the strong filial bonds that exist among families. Because perhaps of this ground, law enforcement agencies hardly use this ground to penalize those who help out other relatives, since such persons would merely be doing what is natural for them under the given circumstances. But this is dangerous, because law enforcement agencies have no choice as to the law which they are to enforce, or even the fact of whether or not to enforce a particular piece of legislation. The act of drafting legislation is in the realm of another political body and the Executive is mandated to apply the law, as it is found. The fact that PD 1829 has not been prosecuted may reveal the reasons why the high rates of criminality have not been abated, despite the efforts of law enforcement agencies. The other acts penalized under PD 1829 which would preventing witnesses from testifying in any criminal proceeding or from reporting the commission of any offense or the identity of any offender/s by means of bribery, misrepresentation, deceit, intimidation, force or threats;[52] or altering, destroying, suppressing or concealing any paper, record, document, or object, with intent to impair its verity, authenticity, legibility, availability, or admissibility as evidence in any investigation of or official proceedings in, criminal cases, or to be used in the investigation of, or official proceedings in, criminal cases.[53] Such acts are logically those which are performed in the course of the prosecution of a criminal. It would be inconceivable that these acts have never been performed in the course of criminal trials in the Philippines. But the fact still remains that hardly has any case been tried and reviewed in the Supreme Court regarding PD 1829, the law which penalizes such acts which constitute the obstruction of justice. Does this mean that litigation has descended to such a level that these acts which should actually constitute obstruction of justice are no longer prosecuted, because both sides the prosecution and defense routinely resort to them anyway, and anyone who complains of such acts by the other party would be asking for relief from the court with unclean hands?

Conclusion: A Law Whose Time Has Come

PD 1829 is essential to the effective functioning of the courts and the effective action of law enforcement agencies. If the pillars of the criminal justice system are to attain the ends by which they were created for, it is necessary that society does not thwart the efforts of the criminal justice system in providing a solution for crimes. The law on obstruction of justice is a law which is actively used in American courts to prosecute those individuals who impede the administration of justice by the performance of certain acts. It is inconceivable that these same acts are not performed in the Philippines. But despite of this inconceivability, there are hardly any cases elevated up to the Supreme Court which charges persons for violations of PD 1829. The law that prohibits obstruction of justice is good law even up to the present time as the government intensifies its campaign against crime. In order to do so, private citizens and other third parties must not deter in the arrest, prosecution and trial of these persons who are charged with crimes. This is no recommendation that the government do everything in order to convict. Rather, this is merely a call on citizens not to impede in the just prosecution of criminal cases. PD 1829 seeks to penalize such behavior that constitutes the obstruction of justice when private citizens are remiss in this duty which they owe to other members of society. But the good aims of the law cannot be met when there has been an observed non-use of the law. Has this arisen out of the reluctant of public officers to involve themselves in charging other with crimes which they find that they themselves could have committed in the first place? This cannot be the case because justice should be blind, in order for it to be fair. And to be fair, law enforcement agencies have to be hard hearted in order to bring about the ends that is contemplated by all criminal laws, that of bring order to society, for the betterment of all that belong to that society.

[1]

Mahatma Gandhi, Seven Blunders of the World That Lead to Violence, available at http://www.quincy.edu/~ hardeja/flag.html (last accessed Aug. 27, 2003). [2] 58 AmJur 2d Obstructing Justice 1. [3] PD 1829, Whereas Clauses 1. [4] Id. 2. [5] Id. [6] 58 AmJur 2d Obstructing Justice 2 (citing People v. Ormsby, 310 Mich 291, 17 NW2d 187; People v. Somma, 123 Mich App 658, 333 NW2d 117, Shackelford v. Commonwealth, 185 Ky 51, 214 SW 788). [7] PD 1829, Sec. 2. [8] Id. Sec. 1 (a). [9] 58 AmJur 2d Obstructing Justice 34. [10] PD 1829, Sec. 1 2.

[11]

Revised Penal Code, Art. 180 penalizes false testimony against a defendant, Art. 181 penalizes giving of false testimony favorable to the defendant, Art. 182 penalizes the giving of false testimony in civil cases, Art. 183 penalizes the giving of false testimony in other cases and perjury in solemn affirmation, and Art. 184 penalizes the offering of false testimony in evidence. [12] Florenz Regalado, Criminal Law Compendium 387-88 (2003). [13] PD 1829, Sec. 1 (b). [14] 58 AmJur 2d Obstructing Justice 43. [15] PD 1829, Sec. 1 (c). [16] Revised Penal Code, Art. 19. [17] Luis B. Reyes, The Revised Penal Code 558-59 (14d ed. 1998). [18] Republic Act 7659, An Act to Impose t he Death Penalty on Certain Heinous Crimes, Amending for That Purpose the Revised Penal Code, as amended, Other Special Penal Laws, and for Other Purposes, imposes the penalty of death on all these crimes, to wit, treason, parricide, murder, kidnap for ransom, destructive arson, qualified rape, and crimes related to prohibited drugs. [19] PD 1829, Sec. 1 (d). [20] Regalado, supra note x, at 379. [21] PD 1829, Sec. 1 (e). [22] 58 AmJur 2d Obstructing Justice 26. [23] PD 1829, Sec. 1 (f). [24] 58 AmJur 2d Obstructing Justice 40. [25] Id. (citing State v. Latimer, 9 Kan App 2d 728, 687 P2d 648. [26] 58 AmJur 2d Obstructing Justice 24. [27] Id. 41. [28] PD 1829, Sec. 1 (g). [29] Revised Penal code, Art. 210 1. [30] Id. 3. [31] Id. 4. [32] PD 1829, Sec. 1 (h). [33] 58 AmJur 2d Obstructing Justice 43. [34] Id. (citing US v. Vixie 532 F2d 1277). [35] Id. (citing US v. Mitchell 372 F Supp 1239). [36] PD 1829, Sec. 1 (i). [37] Id. Sec. 1 (c). [38] 58 AmJur 2d Obstructing Justice 27. [39] Id. [40] G.R. No. 93335, Sept. 13, 1990. [41] 99 Phil. 515 (1956). [42] Enrile v. Amin, supra. [43] G.R. No. 112235, Nov. 29, 1995. [44] 99 Phil. 515, 535-536 (1956). [45] 189 SCRA 573 (1990). [46] GR 127157, July 13, 1998. [47] Id. [48] G.R. No. 144261-62, May 9, 2001. [49] 90 Phil. 49. [50] As defined and punished in Chapter Two to Six, Title Seven of the Revised Penal Code, (referring to the crimes committed by the public officers). [51] 108 Phil. 613. [52] PD 1829, Sec. 1 (a). [53] Id. Sec. 1 (b).

http://www.angelfire.com/ks/cybertarget/SPL_paper.htm

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Florida Sentencing: Basic Law of Sentencing in FloridaDocumento212 pagineFlorida Sentencing: Basic Law of Sentencing in FloridaFlorida SentencingNessuna valutazione finora

- Warrior-Adventurer and GeneralDocumento248 pagineWarrior-Adventurer and GeneralKlenk GáborNessuna valutazione finora

- IRR of RA 9287 (Increasing Penalty For Illegal Numbers Games) PDFDocumento9 pagineIRR of RA 9287 (Increasing Penalty For Illegal Numbers Games) PDFBobby Olavides Sebastian100% (1)

- 86826-2014-Implementing Rules and Regulations ofDocumento9 pagine86826-2014-Implementing Rules and Regulations ofMD GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rule On Cybercrime Warrants: (A.M. No. 17-11-03-SC)Documento48 pagineRule On Cybercrime Warrants: (A.M. No. 17-11-03-SC)Alain Barba100% (1)

- White Light Corp V City of Manila DigestDocumento1 paginaWhite Light Corp V City of Manila DigestApril Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Criminology Criminal Justice Lecture Notes Exam Notes Lecture Notes Lectures 1 13Documento26 pagineIntroduction To Criminology Criminal Justice Lecture Notes Exam Notes Lecture Notes Lectures 1 13Tehseen Kanwal100% (2)

- Anti-Mail Order Spouse ActDocumento1 paginaAnti-Mail Order Spouse ActKarissa TolentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- CCTV and Recording Laws of The PhilippinesDocumento10 pagineCCTV and Recording Laws of The PhilippineswdNessuna valutazione finora

- DOJ Protection Programs and Salient IssuancesDocumento28 pagineDOJ Protection Programs and Salient IssuancesMark Viernes100% (1)

- RA. 11648 - New Rape LawDocumento3 pagineRA. 11648 - New Rape Lawroyel arabejoNessuna valutazione finora

- Miranda Rights and Obstruction of JusticeDocumento3 pagineMiranda Rights and Obstruction of JusticeOllie EvangelistaNessuna valutazione finora

- MediationDocumento6 pagineMediationxty517100% (1)

- Code of Ordinances Davao CityDocumento242 pagineCode of Ordinances Davao CityAlfred LacandulaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vawc ProcedureDocumento5 pagineVawc ProcedureJuan GeronimoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ra 9262 Anti Vawc ActDocumento39 pagineRa 9262 Anti Vawc ActDesireeNessuna valutazione finora

- R.A. No. 10634 PrimerDocumento9 pagineR.A. No. 10634 PrimerLilaben Sacote100% (1)

- Forform Vs PNRDocumento2 pagineForform Vs PNRApril Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- Implementing Rules and Regulations RA 9262Documento31 pagineImplementing Rules and Regulations RA 9262Cesar Valera100% (7)

- 2019 Revised Rule On Children in Conflict With The LawDocumento21 pagine2019 Revised Rule On Children in Conflict With The LawA Thorny RockNessuna valutazione finora

- BPATDocumento36 pagineBPATBielle BlissNessuna valutazione finora

- Ra 9344Documento31 pagineRa 9344Anonymous UFtsUaNessuna valutazione finora

- REPUBLIC ACT 11596 - An Act Prohibiting Child MarriageDocumento20 pagineREPUBLIC ACT 11596 - An Act Prohibiting Child MarriageRic VinceNessuna valutazione finora

- Certification PNP IpilDocumento1 paginaCertification PNP IpilGeneris SuiNessuna valutazione finora

- Crim ProDocumento5 pagineCrim ProBeboy Paylangco Evardo100% (1)

- PD 1829Documento8 paginePD 1829Justin SarmientoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ra 9851 PDFDocumento20 pagineRa 9851 PDFAine Mamle TeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Training On Drafting of OrdinanceDocumento55 pagineTraining On Drafting of OrdinanceLaarni AlgireNessuna valutazione finora

- PracticeDocumento3 paginePracticeFely DesembranaNessuna valutazione finora

- Petition For Probation - Hermilo SolinaDocumento3 paginePetition For Probation - Hermilo SolinaBriar RoseNessuna valutazione finora

- Obstruction of JusticeDocumento8 pagineObstruction of JusticeRey RectoNessuna valutazione finora

- Katarungang PambarangayDocumento7 pagineKatarungang PambarangayMark VernonNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 193854 September 24, 2012 People of The Philippines, Appellee, DINA DULAY y PASCUAL, Appellant. Peralta, J.Documento12 pagineG.R. No. 193854 September 24, 2012 People of The Philippines, Appellee, DINA DULAY y PASCUAL, Appellant. Peralta, J.Ays0% (1)

- CASE DIGEST Commercial LawDocumento7 pagineCASE DIGEST Commercial LawApril Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- Primer On CybercrimeDocumento3 paginePrimer On CybercrimeEmmanuel S. CaliwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Barangay Justice SystemDocumento41 pagineBarangay Justice SystemAaron ValdezNessuna valutazione finora

- Obstruction of Justice (PD 1829)Documento12 pagineObstruction of Justice (PD 1829)Rico Urbano100% (1)

- Jjwa 9344 & 10630 2020Documento34 pagineJjwa 9344 & 10630 2020Geramer Vere Durato100% (1)

- People Vs Ordoo June 29, 2000Documento2 paginePeople Vs Ordoo June 29, 2000April Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- People Vs Ordoo June 29, 2000Documento2 paginePeople Vs Ordoo June 29, 2000April Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- Correctional Administration 2Documento5 pagineCorrectional Administration 2AJ LayugNessuna valutazione finora

- IRR Ra 9165 and AmendmentDocumento35 pagineIRR Ra 9165 and AmendmentThessaloe B. FernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Revised - JJWC PAO TrainingDocumento65 pagineRevised - JJWC PAO TrainingIrwin Ariel D. Miel100% (1)

- Functions of Philippine Government AgenciesDocumento7 pagineFunctions of Philippine Government AgenciesMarc Eric RedondoNessuna valutazione finora

- Petition For The Allowance of A Notarial WillDocumento4 paginePetition For The Allowance of A Notarial WillApril Dream Mendoza Pugon0% (1)

- Ra 9344Documento36 pagineRa 9344Rafael SaturnoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ra 9262Documento77 pagineRa 9262Vincent Quiña PigaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ra 7610Documento12 pagineRa 7610Mae ReyesNessuna valutazione finora

- 205136-2016-Implementing Rules and Regulations Of20210424-14-NDocumento15 pagine205136-2016-Implementing Rules and Regulations Of20210424-14-NAbel Angelo Bayot100% (1)

- PD 1829Documento1 paginaPD 1829Jc IsidroNessuna valutazione finora

- Ra 9262 - IrrDocumento16 pagineRa 9262 - Irrheart leroNessuna valutazione finora

- RA 9344 Guindulman TalkDocumento37 pagineRA 9344 Guindulman TalkRoland ApareceNessuna valutazione finora

- Narciso vs. Sta. Romana-Cruz March 17, 2000Documento2 pagineNarciso vs. Sta. Romana-Cruz March 17, 2000April Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- Cruz Vs - Enrile, 160 SCRA 702 (1988)Documento2 pagineCruz Vs - Enrile, 160 SCRA 702 (1988)LeyardNessuna valutazione finora

- (Stufe 14 x4) Moagims CloneDocumento27 pagine(Stufe 14 x4) Moagims Clone19141914Nessuna valutazione finora

- Katarungang Pambarangay A Lecture Series-Shorter VersionDocumento67 pagineKatarungang Pambarangay A Lecture Series-Shorter VersionJaneth Mejia Bautista Alvarez100% (1)

- Swu Lecture Ra 7610 Ra 9208 and Other Pertinent LawsDocumento70 pagineSwu Lecture Ra 7610 Ra 9208 and Other Pertinent LawsValerie Anne Balani Torrefranca-NaronaNessuna valutazione finora

- People Vs Galit Case DigestDocumento1 paginaPeople Vs Galit Case DigestApril Dream Mendoza Pugon80% (5)

- Ong Vs People DigestDocumento1 paginaOng Vs People DigestApril Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- Rule On CICLDocumento2 pagineRule On CICLTori PeigeNessuna valutazione finora

- TerrorismDocumento3 pagineTerrorismChristian Dave Tad-awan100% (2)

- Committee For The Special Protection of ChildrenDocumento2 pagineCommittee For The Special Protection of ChildrenAnonymous yIlaBBQQNessuna valutazione finora

- Bpo ProcessDocumento21 pagineBpo ProcessFrances Quibuyen DatuinNessuna valutazione finora

- MC 002-02 Relief of AccountabilityDocumento9 pagineMC 002-02 Relief of AccountabilityFerluenz SahagunNessuna valutazione finora

- Enterprise CrimeDocumento23 pagineEnterprise Crimelindseyg89100% (2)

- Philippine Toolkit SextortionDocumento39 paginePhilippine Toolkit SextortionFrances Leryn MaresciaNessuna valutazione finora

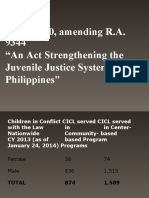

- R.A. 10630, Amending R.A. 9344 "An Act Strengthening The Juvenile Justice System in The PhilippinesDocumento16 pagineR.A. 10630, Amending R.A. 9344 "An Act Strengthening The Juvenile Justice System in The PhilippinesNur SanaaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Crisis Management and Intervention: (Hostage Negotiation)Documento12 pagineCrisis Management and Intervention: (Hostage Negotiation)John Casio100% (1)

- RA 10666 - Children On MotorcyclesDocumento5 pagineRA 10666 - Children On MotorcyclesSa KiNessuna valutazione finora

- CourseheroDocumento4 pagineCourseheromonivmoni5Nessuna valutazione finora

- AffidavitsDocumento9 pagineAffidavitsMosawan AikeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Obstruction of JusticeDocumento3 pagineObstruction of JusticeJohn Ramil RabeNessuna valutazione finora

- Presidential Decree No 1829 - Obstruction of JusticeDocumento4 paginePresidential Decree No 1829 - Obstruction of JusticeBianca BeltranNessuna valutazione finora

- SPLDocumento28 pagineSPLAlyssa GuevarraNessuna valutazione finora

- Prefinals SPLDocumento38 paginePrefinals SPLGillian Alexis ColegadoNessuna valutazione finora

- SPL Group I Part II Gabarra Part 1Documento14 pagineSPL Group I Part II Gabarra Part 1MARK TIMUGEN BELLANessuna valutazione finora

- Digested NPCDocumento8 pagineDigested NPCApril Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- Gardiner Vs MagsalinDocumento2 pagineGardiner Vs MagsalinApril Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digest 1st PropertyDocumento3 pagineCase Digest 1st PropertyApril Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- People Vs Baloloy 381 Scra 31Documento1 paginaPeople Vs Baloloy 381 Scra 31April Dream Mendoza PugonNessuna valutazione finora

- Practice Test EnglishDocumento3 paginePractice Test EnglishZneeky1Nessuna valutazione finora

- "Uncontrolled Desires": The Response To The Sexual Psychopath, 1920-1960Documento25 pagine"Uncontrolled Desires": The Response To The Sexual Psychopath, 1920-1960ukladsil7020Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cases in Law SchoolDocumento79 pagineCases in Law SchoolHei Nah MontanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Film Study - Les MiserablesDocumento2 pagineFilm Study - Les MiserablesHannekeKassiesNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Tyrenzo Morton, 3rd Cir. (2014)Documento4 pagineUnited States v. Tyrenzo Morton, 3rd Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Active and PassiveDocumento7 pagineActive and PassiveEllyAlmNessuna valutazione finora

- First Letter To Korrey MahoneDocumento4 pagineFirst Letter To Korrey MahoneJames Alan BushNessuna valutazione finora

- Collateral Costs: Racial Disparities and Injustice in Minnesota's Marijuana LawsDocumento40 pagineCollateral Costs: Racial Disparities and Injustice in Minnesota's Marijuana LawsMinnesota 2020Nessuna valutazione finora

- MDOC Facilities MapDocumento1 paginaMDOC Facilities MapAnonymous gsQyliXNessuna valutazione finora

- Maria Struzberg - Research PaperDocumento6 pagineMaria Struzberg - Research Paperapi-385768125Nessuna valutazione finora

- Colectionarul Doc. FinalDocumento5 pagineColectionarul Doc. FinalSerban Carmen TeodoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis of Bachan Singh and Machhi Singh and Its ImplicationDocumento9 pagineAnalysis of Bachan Singh and Machhi Singh and Its ImplicationTulika BoseNessuna valutazione finora

- King Lear and The TempestDocumento9 pagineKing Lear and The TempestVesna Dimcic50% (2)

- Gerald Vizenor Compassionate TricksterDocumento4 pagineGerald Vizenor Compassionate TricksterDevidas KrishnanNessuna valutazione finora

- Herras Teehankee vs. RoviraDocumento7 pagineHerras Teehankee vs. RoviraEJ PajaroNessuna valutazione finora

- Phrases and Clauses: (Expanding Simple Sentences Into Complex Sentences)Documento19 paginePhrases and Clauses: (Expanding Simple Sentences Into Complex Sentences)reza rahmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Night Summeraies Samy JDocumento13 pagineNight Summeraies Samy JVictor BascoNessuna valutazione finora

- Betsy Emerick - Dante Auerbach GramsciDocumento15 pagineBetsy Emerick - Dante Auerbach GramsciDionisio MarquezNessuna valutazione finora

- Chhota Bheem Aur KrishnaDocumento3 pagineChhota Bheem Aur KrishnaSmith Jones0% (1)

- Mock Trial Cheat Sheet 4Documento1 paginaMock Trial Cheat Sheet 4Jerry ZhaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Word Formation 4B: Complete The Sentences With The Correct Form of The Words in BracketsDocumento2 pagineWord Formation 4B: Complete The Sentences With The Correct Form of The Words in BracketsVicen PozoNessuna valutazione finora

- There Was A SaviourDocumento19 pagineThere Was A SaviourSrourNessuna valutazione finora

- Caver v. Michigan Department of Corrections Et Al - Document No. 3Documento3 pagineCaver v. Michigan Department of Corrections Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora