Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

14 Crimean Gothic

Caricato da

Ernesto GarcíaDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

14 Crimean Gothic

Caricato da

Ernesto GarcíaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1

A letter in a Letter: a textual note on Busbecqs Crimean Gothic cantilena

ei saiandans saiaima jah gaumjaima 1. Our knowledge of Crimean Gothic is extremely limited. We have only one small corpus of data, comprising: two lists of words and phrases glossed in Latin, eighteen cardinal numbers, and the unglossed, three-line beginning of a song, the cantilena, all told a mere 101 separate forms (Stearns 1978: 3). This is to be found in Busbecqs Fourth Turkish Letter (dated 1562), first published in Augerii Gislenii Busbequii D. legationis Turcic epistol quatuor..., Paris 1589 Apud Egidium Beys, via Iacoba, ad insigne Lilij albi (see Renouard 1979: 312-322 on Beys, and no. 460 on the edition; the title page is illustrated in Stearns 1978: 21). The report of Crimean Gothic is on pages 135a to 137a. However, it is not just the paucity of the material itself, but also the nature of its transmission, that restricts our knowledge of this dialect of Germanic. This is because the printed text of Busbecqs report is several removes from the living language underlying it, which Stearns designates Native Crimean Gothic (1978: 3). (1) Though a Germanic language is known to have been spoken in the Crimea (cf. Stearns 1978: chapter 1), our data do not derive from any native-speaker, but (2) from a Crimean Greek who had learnt Crimean Gothic (cf. Stearns 1978: 45-47). As he was not bilingual from birth, we must reckon with the possibility of sub-stratum effects from his mother-tongue (cf. Stearns 1978: 47-63). (3) Our information does not derive directly from this man, but was written down at his dictation in Constantinople. (4) Moreover, Busbecq, the transcriber, was Flemish, so again we cannot exclude the possibility that there might have been some interference from his own Germanic language in recording the words (he did not use a phonetic script), especially those words he considered to be similar to his own (cf. Stearns 1978: 68-86). (5) The uncertainties are further compounded by the fact that our published version is an unauthorized one, not directly based on Busbecqs original field-notes, nor indeed on his original Letter, but on one of the copies of it that were privately circulated in humanistic circles. (6) It further appears that a number of errors were introduced at the printing stage, either by misreading or mistakes in typesetting (cf. Stearns 1978: 42-44). In view of this state of affairs, we cannot but be grateful to Edward Schrder for clarifying the relationship between the printed editions, by showing (1910: 3-12) that all subsequent editions of Busbecqs report of the Crimean Gothic language derive directly or indirectly from the first edition of the Fourth Turkish Letter, Paris 1589. (Schrder also listed and discussed errors that can be attributed to this edition, 1910: 12-15). 2.1. It is the purpose of this note to bring to notice a further potential distortion of the data in the course of the transmission from Native Crimean Gothic to the first printed edition of Busbecq's report, and thereby to correct a misreading of it. This additional source of error was introduced at the very latest stage and is of a purely mechanical nature, for it concerns the contact of type with paper during the actual business of printing.

2 2.2. Stearns has already drawn attention to the various readings of Galtzou, the last word of the second line of the cantilena (1978: 121 fn1, cf. 10 fn22). This form appears as Galtzu in the Frankfurt edition of 1595 (and all subsequent editions) as a result of a typesetting error. What is of interest here, however, is the way scholars have variously reported these forms as Galtzou or Galizou, respectively Galtzu or Galizu, reading the fourth letter as a t or an undotted i. I myself differ from Schrder in reading Frankfurt 1595, Hanau 1605, as Galtzu (Schrder Galizu), cf. also Stearns 1978: 121 fn1. propos this phenomenon, Stearns remarks (1978: 121 fn1): It is possible that during the printing of the first edition the type t used in Galtzou was in some way affected, so that in some copies the printed letter took on the appearance of an (undotted) i. 2.3. I would like to suggest that an analogous situation obtains with the first word of the second line of the cantilena, which has always been quoted as Scu. I have consulted seven copies of the Paris edition of 1589 (Renouard 1979: no. 460), and eight copies of the 1595 Paris re-issue of the same printing with a cancel title-page (see Renouard 1979: no. 462; the re-issue is not mentioned by either Schrder or Stearns, and seems not to be widely known in the literature on Crimean Gothic).1 In all but one of these copies, I read the relevant word as Seu: the understroke of the bow of the e is fainter than the topstroke, though the degree of faintness varies. However, in the Dresden copy the second character of the first word of line two actually does look more like a c than any other letter, albeit with a thickening of the upper curve. There is no clear sign of the understroke of an e and without having consulted other copies of the book, one would probably most naturally read the letter as a c. Probably, the best quality printing of the copies I have seen is that of the 1595 reissue in the Bibliothque Nationale, Paris, with the shelfmark Z 13939: the understroke of the e in Seu, though faint, is clear, and a number of is, apparently undotted in other copies, are here seen to have their dot. This or a similarly good print should be used for any future facsimiles. In the Harvard copy reproduced by Stearns (1978: 21-26), the understroke of the e in Seu is presumably particularly faint, for Stearns prints the word as Scu (1978: 121). Unlike the t of Galtzou, which Stearns regards as having been damaged or worn during the course of printing, it seems that the e of Seu was defective from the start. Evidently, this adversely affected its ability to take ink. 2.4. On the question of why the correct reading should hitherto have been missed, I can offer the following thoughts. (1) Until the publication of Schrders article in 1910, many scholars did not use the first edition. The Frankfurt edition of 1595, previously the most widely used (and believed by some to be the first, cf. Schrder 1910: 4 fn1), actually does have the reading Scu.2 (2) In some copies of the first edition, the understroke of the bow of the e may be so faint as to be barely, if at all, visible, as in the Dresden copy. (It seems that the Frankfurt edition must have been prepared from such an exemplar unless the reading Scu is, like Galtzu, the result of a type-setting error.) Stearns has already pointed out that Loewe used a defective copy for his influential study of 1896 (Stearns 1978: 121 fn1, in connection with Loewes reading Galizou for Galtzou, cf. 2.2). Streitberg

3 reproduced Loewes text in the second and subsequent editions of his Gotisches Elementarbuch (1906: 316-318, etc.; Loewes book appeared too late for inclusion in the 1897 first edition of Streitbergs book, whose preface is dated 1. Okt. 1896). I take it that most scholars have relied on Loewe and Streitberg for the primary data. (3) Most importantly, the Gttingen copy that Schrder consulted (1910: 16) itself has a very faint understroke on the e. It also has a poorly printed t, with the left part of the crossstroke barely visible. We may note that, like Loewe (and Streitberg), Schrder reads Galizou (1910: 8; cf. also his testament to the accuracy of Loewe, 4-5). Thus this and the reading Scu were undisputed by Schrder, and the two readings therefore had the authority of all three scholars.3 (4) It is also possible that the fact that the cantilena was unglossed, uninterpreted, and also widely believed actually to be in Turkish, may have diverted attention from it and its forms. 3. I also read Seu in some of the later editions of Busbecqs Fourth Turkish Letter, namely Amsterdam 1660, London 1660, Dresden (Leipzig) 1689. These all go back to the first Elzevir edition, Leiden 1633 (A. Gislenii Busbequii omnia quae extant), cf. Schrder 1910: 10-11. This reads Scu, however (though see below), as do the two other editions, which, according to Schrder, are based on it: Oxford 1660, Basel 1740. As these Seueditions all derive from that of 1633, it would appear that this reading did not arise through collation with the first edition (they all read Galtzu/Galizu), but is an unconnected aberration, born no doubt of the inherent confusability of c and e. From the point of view of Busbecqs report, these particular readings are of no relevance, since, as shown by Schrder, it is only the first edition of 1589 and its 1595 re-issue that matter. In addition, the London edition of 1660, which Schrder says derives directly from the Elzevir edition of 1633 (1910: 11), contains the reading ut fecisti for tu fecisti in the word list, a change which, according to Schrder, first occurred in the second Elzevir edition, Amsterdam 1660. In all fairness to Schrder, it must be pointed out that he was unable to consult the London edition. In fact, it would seem that there are actually TWO Elzevir editions bearing the title-page Lugd. Batavorum 1633: one (1633a), which reads tu fecisti and Scu, and one (1633b) which reads ut fecisti and Seu. The ut/tu fecisti and the preceding gloss, ebibe calicem, stand out from the surrounding glosses by beginning with lower-case letters in both these 1633 editions4; in the 1660 Elzevir edition, these two glosses both begin with upper-case letters: Ebibe calicem and Ut fecisti. The London edition of 1660 has the same readings as 1633b. Schrder must have consulted a copy of 1633a. As Schrders main thesis, the priority of the Paris edition of 1589, still stands, it is doubtful what value a detailed re-examination of the later editions would have. I have not been able to undertake one. Patrick V. Stiles, London Notes

4 1. The copies of the 1589 Paris edition that I have seen are: British Library, London; Bodleian Library, Oxford (two copies); Library of Kings College, Cambridge; Bibliothque Nationale, Paris; Niederschsische Staats- und Universittsbibliothek, Gttingen; Schsische Landesbibliothek Staats- und Universittsbibliothek, Dresden. The 1595 Paris re-issue I have consulted in the copies of: Library of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London; Bodleian Library, Oxford; Library of Balliol College, Oxford; National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh; Bibliothque Nationale, Paris (two copies); Bibliothque Sainte Genevive, Paris; Universiteitsbibliotheek, Amsterdam. I would like to thank the staffs of these institutions for their kind assistance. 2. Unaccountably, Scardigli (1973: 24649) prints Busbecqs report on Crimean Gothic from the Basel edition of 1740 (cf. Schrder 1910: 11). 3. According to Renouard 1979: 370, 372, there are only two copies of the Paris printing of Busbecqs Four Turkish Letters in Germany. They are both of the 1589 first edition and are located in Gttingen (the copy consulted by Schrder) and Dresden. Unfortunately, Loewe, who was based in Berlin at the time, does not indicate which copy of the Paris 1589 edition he used for his text (1896: 12730). However, on the basis of his reading of Galtzou as Galizou (cf. 2.2, 2.4), it may have been the Gttingen copy, as its t is somewhat unclear, in contrast to the one in the Dresden copy. So it is at least possible that both he and Schrder had recourse to the same volume in Gttingen University Library. As noted above, Streitberg, merely reproduced Loewes text. However, the main point is that both the copies in Germany have particularly c-like letters. It is also possible, although less likely, that Loewe consulted a copy outside Germany. The only copy in America is at Harvard University. Incidentally, there are more copies of both Beys versions than are listed in Renouard 1979 (a new edition is in preparation). From various online library catalogues come the following additions: 1589 edition: Aix-en-Provence, Bibliothque Mjanes (a second copy); Lyon, Bibliothque municipale; Orlans, Bibliothque municipale: 1595 reissue: La Rochelle, Mdiathque Michel Crpeau; Lyon, Bibliothque municipale; Budapest, Orszgos Szchnyi Knyvtr. It also turns out that there are two more copies belonging to the Bibliothque Nationale in Paris, in the collection of La Bibliothque de lArsenal. 4. ebibe calice and tu fecisti are the only two glosses to start with lower case letters in the first edition. This is presumably to save space and fit the text within the print area, as these are the longest lines on the page (136b col ii). Note the contraction on calice and compare Sciete. Mittere aggit. on page 136a col ii, also the longest line.

REFERENCES Loewe, Richard (1896) Die Reste der Germanen am schwarzen Meere: eine ethnologische Untersuchung. Halle. Renouard, Philippe (1979) Imprimeurs & libraires parisiens du xvie sicle. Ouvrage publi d'aprs les manuscrits de Philippe Renouard. Vol. III. Paris. Scardigli, Piergiuseppe (1973) Die Goten: Sprache und Kultur. Mnchen: CH Beck. Schrder, Edward (1910) Busbecqs Krimgotisches Vokabular. Nachrichten der kniglichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Gttingen. Philologisch-historische Klasse. 116. Stearns, MacDonald Jr. (1978) Crimean Gothic. Analysis and Etymology of the Corpus. (Studia linguistica et philologica 6) Saratoga. Streitberg, Wilhelm (1906) Gotisches Elementarbuch. 2. verbesserte und vermehrte Auflage. Heidelberg. [An earlier version of this article appeared in Neophilologus 68 (1984) 63739. ] Published in Gothica Minora IV (2005).

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- GARDINER, Alan - The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses IIDocumento61 pagineGARDINER, Alan - The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses IISamara Dyva100% (4)

- The Key of SolomonDocumento142 pagineThe Key of Solomonnorriott100% (7)

- Reply of The Zaporozhian CossacksDocumento16 pagineReply of The Zaporozhian CossacksElder FutharkNessuna valutazione finora

- R.I.Page - The Icelandic Rune-PoemDocumento39 pagineR.I.Page - The Icelandic Rune-PoemSveinaldr100% (2)

- The Sogdian Fragments of The British LibraryDocumento40 pagineThe Sogdian Fragments of The British LibraryanhuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Greater Key of Solomon in Five Books - Peterson Edition - 2010Documento292 pagineThe Greater Key of Solomon in Five Books - Peterson Edition - 2010Kahel_Seraph100% (7)

- The Key of SolomonDocumento133 pagineThe Key of SolomonPulbere Neagra100% (9)

- Deissmann Light From EastDocumento690 pagineDeissmann Light From Eastjoseluiscalvo100% (1)

- Listado PublicacionesDocumento95 pagineListado PublicacionesErnesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- Physiotherapy Course PDFDocumento156 paginePhysiotherapy Course PDFMamta100% (1)

- The Textus ReceptusDocumento79 pagineThe Textus ReceptusperepinyolNessuna valutazione finora

- Lancelot of the Laik A Scottish Metrical RomanceDa EverandLancelot of the Laik A Scottish Metrical RomanceNessuna valutazione finora

- Anti-Achitophel (1682) Three Verse Replies to Absalom and Achitophel by John DrydenDa EverandAnti-Achitophel (1682) Three Verse Replies to Absalom and Achitophel by John DrydenNessuna valutazione finora

- The Letters of Cassiodorus Being A Condensed Translation Of The Variae Epistolae Of Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus SenatorDa EverandThe Letters of Cassiodorus Being A Condensed Translation Of The Variae Epistolae Of Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus SenatorNessuna valutazione finora

- HieraticPalaeo IDocumento13 pagineHieraticPalaeo IMarwa EwaisNessuna valutazione finora

- Anonymous - History of Nordic Runes p7Documento29 pagineAnonymous - History of Nordic Runes p7Bjorn AasgardNessuna valutazione finora

- Early English Alliterative Poems in the West-Midland Dialect of the Fourteenth CenturyDa EverandEarly English Alliterative Poems in the West-Midland Dialect of the Fourteenth CenturyNessuna valutazione finora

- I. The Seventeenth Century To C. 1680: by Edward HeawoodDocumento37 pagineI. The Seventeenth Century To C. 1680: by Edward HeawoodHonglan HuangNessuna valutazione finora

- R. Van Bremen, A Family From Syllion, ZPE 104 2004Documento16 pagineR. Van Bremen, A Family From Syllion, ZPE 104 2004Gábor Szlávik100% (1)

- Aufsätze: An Early Isocrates Papyrus (Philippus 1-2)Documento9 pagineAufsätze: An Early Isocrates Papyrus (Philippus 1-2)Rodney AstNessuna valutazione finora

- Annals of OperaDocumento902 pagineAnnals of OperaOmar Dal PossoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Art of The Unmeasured Prelude For Harpsichord: France 1660-1720Documento4 pagineThe Art of The Unmeasured Prelude For Harpsichord: France 1660-1720CarloV.ArrudaNessuna valutazione finora

- Revue Des Études Juives. 1880. Volume 57.Documento350 pagineRevue Des Études Juives. 1880. Volume 57.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNessuna valutazione finora

- The Poetical Works of John MiltonDa EverandThe Poetical Works of John MiltonValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (183)

- The Complete Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge Vol I (of II)Da EverandThe Complete Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge Vol I (of II)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chronicle of Smbat SparapetDocumento87 pagineChronicle of Smbat SparapetRobert G. BedrosianNessuna valutazione finora

- Textus ReceptusDocumento15 pagineTextus Receptuselyhu82100% (1)

- 40a Ast-Hickey - P.Messeri45 - LegalProceedingsDocumento4 pagine40a Ast-Hickey - P.Messeri45 - LegalProceedingsRodney AstNessuna valutazione finora

- The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night — Volume 15Da EverandThe Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night — Volume 15Nessuna valutazione finora

- Grabados AntipapalesDocumento8 pagineGrabados AntipapalesJennifer BrownNessuna valutazione finora

- Kingpin and His ServantsDocumento709 pagineKingpin and His ServantsAnkit TewariNessuna valutazione finora

- P Oxy LXXXIII 5345 Text and ImageDocumento5 pagineP Oxy LXXXIII 5345 Text and ImageTheo NashNessuna valutazione finora

- Douglas Frayne Sargonic and Gutian Periods, 2334-2113 BCDocumento182 pagineDouglas Frayne Sargonic and Gutian Periods, 2334-2113 BClibrary364100% (3)

- Opera Omnia Desiderii Erasmi 1.1Documento704 pagineOpera Omnia Desiderii Erasmi 1.1Professore2100% (1)

- Spenser Bio DetailsDocumento351 pagineSpenser Bio DetailsNsgNessuna valutazione finora

- Gildersleeves Latin GrammarDocumento709 pagineGildersleeves Latin Grammartomochan2002Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Noble Spanish Soldier by Dekker, Thomas, 1572-1632Documento79 pagineThe Noble Spanish Soldier by Dekker, Thomas, 1572-1632Gutenberg.orgNessuna valutazione finora

- Hieratic Paleography: Written Egyptian How It Developed From The 5th Dynasty To Roman TimesDocumento12 pagineHieratic Paleography: Written Egyptian How It Developed From The 5th Dynasty To Roman TimesArch. MarioNessuna valutazione finora

- Hadriani SententiaeDocumento14 pagineHadriani Sententiaealejandro_fuente_3Nessuna valutazione finora

- Selections from Early Middle English 1130-1250: Part II: NotesDa EverandSelections from Early Middle English 1130-1250: Part II: NotesNessuna valutazione finora

- Anonymous - History of Nordic Runes p7 Cd9 Id1012737710 Size348Documento30 pagineAnonymous - History of Nordic Runes p7 Cd9 Id1012737710 Size348Baud WolfNessuna valutazione finora

- Prefaces to Terence's Comedies and Plautus's Comedies (1694)Da EverandPrefaces to Terence's Comedies and Plautus's Comedies (1694)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Seminarium Kondakovianum 1936 Vyp 08Documento330 pagineSeminarium Kondakovianum 1936 Vyp 08Keyser SozeNessuna valutazione finora

- Two Sketches For Alban Berg's Lulu - Patricia HallDocumento7 pagineTwo Sketches For Alban Berg's Lulu - Patricia Hallraummusik100% (1)

- Brock - 1967 - Greek Words in The Syriac Gospels (Vet and Pe)Documento39 pagineBrock - 1967 - Greek Words in The Syriac Gospels (Vet and Pe)andreimacarNessuna valutazione finora

- O Livro de Como Se Fazen As Cores em JodeoportuguesDocumento69 pagineO Livro de Como Se Fazen As Cores em JodeoportuguesNuno Matos100% (1)

- VIRGINIA COX, An Unknown Early Modern New World Epic: Girolamo Vecchietti's Delle Prodezze Di Ferrante Cortese (1587-88)Documento40 pagineVIRGINIA COX, An Unknown Early Modern New World Epic: Girolamo Vecchietti's Delle Prodezze Di Ferrante Cortese (1587-88)fusonegroNessuna valutazione finora

- Horner. The Coptic Version of The New Testament in The Northern Dialect. 1898. Volume 3.Documento712 pagineHorner. The Coptic Version of The New Testament in The Northern Dialect. 1898. Volume 3.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNessuna valutazione finora

- Grottasǫngr. Ed. Clive TolleyDocumento68 pagineGrottasǫngr. Ed. Clive TolleyMihai Sarbu100% (1)

- The 1640 Text of Shakespe PDFDocumento15 pagineThe 1640 Text of Shakespe PDFVictor informaticoNessuna valutazione finora

- Bestiary of Philippe de Thaon - Wright - Parallel Text PDFDocumento57 pagineBestiary of Philippe de Thaon - Wright - Parallel Text PDFAnca CrivatNessuna valutazione finora

- About This Recording: - FROBERGER, J.J.: 23 Suites / Tombeau / Lamentation (G. Wilson)Documento8 pagineAbout This Recording: - FROBERGER, J.J.: 23 Suites / Tombeau / Lamentation (G. Wilson)ambroise Kim ambroisesogang.ac.krNessuna valutazione finora

- Wagner Prose Works Vol6Documento416 pagineWagner Prose Works Vol6Francisco Caja López100% (1)

- The Prelude: "Fill your paper with the breathings of your heart."Da EverandThe Prelude: "Fill your paper with the breathings of your heart."Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gardiner The Autobiography Rekhmere 1925Documento16 pagineGardiner The Autobiography Rekhmere 1925Walid ElsayedNessuna valutazione finora

- Luke John MurphyHerjans DísirDocumento167 pagineLuke John MurphyHerjans DísirErnesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- Yggdrasil and The Well of UrdDocumento5 pagineYggdrasil and The Well of UrdErnesto García100% (1)

- TrøllabundinDocumento1 paginaTrøllabundinErnesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- The White Viking I: '$& B W M SDocumento1 paginaThe White Viking I: '$& B W M SErnesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- 08 Ac17Documento10 pagine08 Ac17Ernesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- This CroatDocumento2 pagineThis CroatErnesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- ( Viaticum) Used To Designate Extreme UnctionDocumento1 pagina( Viaticum) Used To Designate Extreme UnctionErnesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- About A Reconstructed Word For TuesdayDocumento51 pagineAbout A Reconstructed Word For TuesdayErnesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- Course Unit TitleDocumento2 pagineCourse Unit TitleErnesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- Asatru - The Native Religion-BDocumento2 pagineAsatru - The Native Religion-BErnesto García100% (1)

- Mjok Trollaukinn) - The Perspective Has Changed, and Erlendsson AttriDocumento1 paginaMjok Trollaukinn) - The Perspective Has Changed, and Erlendsson AttriErnesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Good Death Is A Guarantee of Posthumous Rest. (Savonarola, Predica Del Arte Del Bene Morire, Florence, 1495)Documento1 paginaA Good Death Is A Guarantee of Posthumous Rest. (Savonarola, Predica Del Arte Del Bene Morire, Florence, 1495)Ernesto GarcíaNessuna valutazione finora

- English: Quarter 2 - Module 3 Argumentative Essay: Writing It RightDocumento31 pagineEnglish: Quarter 2 - Module 3 Argumentative Essay: Writing It RightMercy GanasNessuna valutazione finora

- List of Institute of PGDM With AddressDocumento6 pagineList of Institute of PGDM With AddressSayon DasNessuna valutazione finora

- Current Assessment Trends in Malaysia Week 10Documento13 pagineCurrent Assessment Trends in Malaysia Week 10Gan Zi XiNessuna valutazione finora

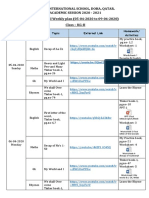

- Loyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIDocumento3 pagineLoyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIAvik KunduNessuna valutazione finora

- Sheet: NameDocumento8 pagineSheet: NameJaneNessuna valutazione finora

- University of Gondar Academic Calendar PDF Download 2021 - 2022 - Ugfacts - Net - EtDocumento3 pagineUniversity of Gondar Academic Calendar PDF Download 2021 - 2022 - Ugfacts - Net - EtMuket AgmasNessuna valutazione finora

- A Feminist Criticism On The MovieDocumento3 pagineA Feminist Criticism On The MovieAnna Mae SuminguitNessuna valutazione finora

- Michigan School Funding: Crisis and OpportunityDocumento52 pagineMichigan School Funding: Crisis and OpportunityThe Education Trust MidwestNessuna valutazione finora

- Outside Speaker EvaluationDocumento2 pagineOutside Speaker EvaluationAlaa QaissiNessuna valutazione finora

- Aimless ScienceDocumento19 pagineAimless Scienceaexb123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aparchit 1st August English Super Current Affairs MCQ With FactsDocumento27 pagineAparchit 1st August English Super Current Affairs MCQ With FactsVeeranki DavidNessuna valutazione finora

- Be A Frog, A Bird, or A TreeDocumento45 pagineBe A Frog, A Bird, or A TreeHWelsh100% (2)

- By: Nancy Verma MBA 033Documento8 pagineBy: Nancy Verma MBA 033Nancy VermaNessuna valutazione finora

- Saloni LeadsDocumento3 pagineSaloni LeadsNimit MalhotraNessuna valutazione finora

- Application Form SaumuDocumento4 pagineApplication Form SaumuSaumu AbdiNessuna valutazione finora

- NSTP Cwts CompleteDocumento115 pagineNSTP Cwts Completehannadace04Nessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Arts in The Elementary Grades: OgdimalantaDocumento12 pagineTeaching Arts in The Elementary Grades: OgdimalantaDiana Rose SimbulanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Wick: The Magazine of Hartwick College - Summer 2011Documento56 pagineThe Wick: The Magazine of Hartwick College - Summer 2011Stephanie BrunettaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative AnalysisDocumento11 pagineThe Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative AnalysisDani Ela100% (1)

- Coping Mechanism of SHS Students in Transitioning Adm To F2F Mode ClassesDocumento5 pagineCoping Mechanism of SHS Students in Transitioning Adm To F2F Mode ClassesPomelo Tuquib LabasoNessuna valutazione finora

- Interview Different TypesDocumento2 pagineInterview Different Typesআলটাফ হুছেইনNessuna valutazione finora

- Overconfidence BiasDocumento2 pagineOverconfidence BiasteetoszNessuna valutazione finora

- Resume ESL Teacher-DaejeonDocumento3 pagineResume ESL Teacher-Daejeonben_nesbit100% (3)

- InclusionDocumento18 pagineInclusionmiha4adiNessuna valutazione finora

- CHED E-Forms A B-C Institutional, Programs, Enrollment and Graduates For Private HEIs - AY0910Documento7 pagineCHED E-Forms A B-C Institutional, Programs, Enrollment and Graduates For Private HEIs - AY0910ramilsanchez@yahoo.com100% (2)

- Future TensesDocumento3 pagineFuture TensesAndrea Figueiredo CâmaraNessuna valutazione finora

- SPA Daily Lesson Log g8 Nov. 21 25Documento2 pagineSPA Daily Lesson Log g8 Nov. 21 25Chudd LalomanNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan 50 Min Logo DesignDocumento3 pagineLesson Plan 50 Min Logo Designapi-287660266Nessuna valutazione finora

- Formulir Aplikasi KaryawanDocumento6 pagineFormulir Aplikasi KaryawanMahesa M3Nessuna valutazione finora