Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Micronutrients

Caricato da

Somya MehndirattaDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Micronutrients

Caricato da

Somya MehndirattaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Micronutrients Micronutrients include all vitamins and minerals.

Required in only tiny amounts, they are nonetheless essential for life and needed for a wide range of body functions. Vitamins are either water-soluble (e.g. such as the B complex vitamins and vitamin C) and generally not stored by the body for future needs, or fat-soluble (e.g., vitamins A and D), which can be stored by the body. Micronutrient deficiency diseases (MDD) are widespread and affect large numbers of people in developing countries. Approximately 2 billion people worldwide suffer from some kind of micronutrient deficiency, causing a wide array of disorders and increasing the risk of death, disease and disability. For example, between 250,000 and 500,000 children a year become blind because of Vitamin A Deficiency (VAD). One quarter of the worlds people suffers from Iodine Deficiency Disorder (IDD), causing not only widespread endemic goitre but also retarding growth, physical and mental development; in its extreme form, this retarded growth is known as cretenism. Anaemia, or Iron Deficiency Anaemia (IDA) characterised by breathlessness and fatigue - is also prevalent worldwide and, unlike deficiencies in vitamin A and iodine, occurs in both industrialized and developing countries. Micronutrients are variously distributed in food. Some micronutrients, such as riboflavin, are widely available in a range of foods and hence deficiencies of these are extremely unusual. Deficiencies are more common when a particular micronutrient, such as Vitamin A, is found in only a limited range of food. An individuals requirement for different micronutrients depends on age and sex. There are also key periods when micronutrient requirements increase: pregnancy and lactation, early infant and child growth, and during certain illnesses. There is a risk of toxicity with excessive intakes of some micronutrients; a high intake of vitamin A, for example, is especially dangerous for pregnant women as damage to the growing baby can occur.

Iron Iron is an essential element in the diet. It is a component of body systems that are involved in the utilization of oxygen. It forms part of haemoglobin, the red pigment in blood, which allows oxygen to be carried from the lungs to the tissues. We cannot use all food sources of iron with equal efficiency. This means that not all of the iron consumed is available to our bodies. Animal sources of iron are more readily utilized than those from plant foods. The recommended dietary intake for iron takes into account the varying availability of the iron from food. The presence of vitamin C in the meal can enhance the availability of iron. Iron deficiency is the most commonly occurring nutrient deficiency. In healthy people, iron deficiency can occur in infancy, during periods of rapid growth, from menstruation, and in

pregnancy. Additional amounts of iron are needed during these periods. Blood loss and disorders of the gastrointestinal tract can also lead to deficiency. Severe iron deficiency can result in anaemia. Dietary Sources: Liver is by far the richest iron-containing food. Other good sources of ironrich foods include organ meats, and poultry. Dried beans and vegetables are the best plant sources, followed by dried fruits, nuts, and whole grain breads and cereals. Fortification of cereals, flours, and bread with iron has contributed significantly to daily dietary iron consumption. Zinc Our bodies need zinc for many different functions, which include protein and carbohydrate metabolism for the immune system, wound healing, growth and vision. The dietary requirement for zinc must take into account the different degree of availability of zinc in different foods. Animal products are more efficient sources compared with cereals. The recommended dietary intake for zinc assumes that the zinc comes from mixed animal and plant sources. For people who do not eat animal products a higher intake may be necessary. Several groups of people are at risk of developing dietary zinc deficiency. If you restrict your food to vegetables, and particularly wholegrain cereals, you could become deficient in zinc. Although zinc is present in these foods, it is not utilized by the body as efficiently as the zinc in other sources, such as meat, eggs and liver. Zinc deficiency also appears to be a problem in some disease states. Inadequate zinc intake can result in retarded growth, delayed wound healing, reduced immune system, loss of taste sensation and dermatitis. Dietary Sources: The best dietary sources of zinc are lean meats, liver, eggs, and seafood. Whole grain breads and cereals are also good sources of zinc. Iodine Our bodies must have an adequate intake of iodine to form the hormones produced by the thyroid gland. These hormones regulate our bodies' metabolic rate. If the dietary level of iodine is inadequate, the gland, which is in the neck, swells, a condition called goiter. The fact that the mother is iodine deficient during pregnancy may affect brain development of the child, it can cause mental retardation and stunted growth in children, and hair loss, slowed reflexes, dry, coarse skin and other effects in adults. Foods produced in regions where soils are low in iodine, are deficient in this element. Iodine deficiency can be prevented by supplementing the diet with added iodine. This is commonly done by adding sodium iodidate to table salt to produce iodized salt. For some people, iodized salt can be an important source of iodine. Some foods, such as cabbage, sprouts and other brassicas contain natural anti-thyroid substances. In circumstances where both large quantities of these foods are eaten and the levels of dietary iodine are marginal, Iodine Deficiency Disorders could develop. Excessive amounts of iodine can also lead to goitre. This has occurred where foods, such as

seaweeds, which are rich in iodine, are commonly eaten. Although excessive iodine intake is not common, it should be noted that, in addition to food, many cough medicines and milk contaminated with an iodine containing sanitizing agent also contribute to iodine intake. But it is unlikely that any harmful effects would occur with habitual intakes up to 300 micrograms per day. Dietary Sources: Iodized salt is the most common source of iodine. Iodine-rich foods include seafood, sea vegetables (seaweed), kelp, and vegetables grown on iodine-rich soils. Calcium Calcium, in combination with phosphorus and other elements, is necessary to give strength to bones and teeth. When our dietary intake of calcium is greater than our bodies' requirements some of the excess calcium is stored in our bones. When our day-to-day intake of calcium does not meet requirements, the calcium stored in bone becomes available to meet this shortfall. Calcium has other important roles. It is essential for normal clotting of blood and is a vital link in transmission of nerve impulses. It is also an essential element in enzyme regulation, in the secretion of insulin in adults, and in regulation of muscle function. During periods of growth the demand for calcium is greater than usual, although some calcium is incorporated into bone at certain other stages of life. Thus children, adolescents and pregnant and lactating women need additional calcium. Adults continually need to replace calcium that is lost from the body in urine and faeces and to a lesser extent in sweat. Our bodies' utilization of the calcium in food can be adversely affected by the presence of two chemicals called phytic acid and oxalic acid. Phylic acid is found in the bran portion of cereals (e.g. when whole-whet flour is used such as for making chapatis), and oxalic acid is present in significant quantities in spinach and rhubarb. The magnitude of the effect depends on the amount of these acids we consume and a higher intake of calcium may be necessary if large quantities of foods containing oxalic and/or phytic acids are eaten. There are three skeletal diseases associated with calcium deficiency. Rickets is the classical calcium deficiency disease. It occurs in children and causes a variety of bone deformities. When this condition develops in adults, it is called osteomalacia. Osteoporosis is associated with a lack of vitamin D, which causes a reduction in the absorption of calcium and makes the bones weaker. The symptoms of calcium deficiency include muscle cramps, heart palpitations, high blood pressure, brittle or soft bones, tooth decay, back and leg pains, insomnia, and nervous disorders Dietary Sources: Milk and dairy products are the major source of dietary calcium for most people. Other good sources are dark green leafy vegetables, broccoli, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.

Vitamin A Some foods contain both vitamin A itself, and other substances that can be converted to vitamin A, known as provitamin A, vitamin A precursors or carotenoids. Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin. It is therefore necessary to have some fat in the diet for these vitamins to be adequately absorbed. Vitamin A is required for the normal functioning of the eyes, the immune system, growth and development, maintenance of healthy skin, and reproduction. One of the most important consequences of vitamin A deficiency are reduced immunity and increased susceptibility to infectious diseases, but also dryness of the eyes eventually leading to blindness. It remains one of the main causes of blindness in the world. Night blindness is also an eye complication of early vitamin A deficiency. Vitamin A is present in food in two forms, as preformed vitamin A (retinol) contained in foods of animal origin and easily absorbed, and as carotenoids (largely -carotene) contained in plant foods, these can be biologically transformed to vitamin A but are less easily absorbed Food sources: Good food sources of vitamin A include liver, kidney, butter, egg yolk, whole milk and cream, and fortified skim milk. Good food sources of beta-carotene (pro-vitamin A) include yellow and dark leafy green vegetables (carrots, collards, spinach, sweet potatoes, squash) and yellow fruit (apricots, peaches, cantaloupe). Cod liver oil and halibut fish oil contain high levels of vitamin A. Vitamin D Vitamin D refers to two biologically inactive precursors D3, also known as cholecalciferol, and D2, also known as ergocalciferol. The former, produced in the skin on exposure to UVB radiation (290 to 320 nm), is said to be more bioactive. The latter is derived from plants and only enters the body via the diet. People who are mainly dependent on dietary vitamin D, which is fat-soluble, may be deficient in the vitamin, since poor absorption of vitamin D can occur because of poor fat absorption. Also, for the full action of vitamin D it must be further metabolized in liver and kidney, which means that disorders of these organs can lead to vitamin D deficiency. The main function of vitamin D in humans is to regulate calcium and phosphorus metabolism. Its deficiency in children leads to rickets and in adults to osteomalacia, both of which are disorders of bone. Food sources: Vitamin D does not occur in significant amounts in many foods. It occurs in small and highly variable amounts in butter, cream, egg yolks, and liver.

Other source: sunlight exposure Vitamin E Vitamin E originates from plants. It is found in vegetable oils such as corn, olive, palm, peanut and cotton-seed oils. Animals acquire their vitamin E from plants directly, or by eating other animals that have derived their vitamin E from plants and stored it in their liver, muscles and fat. Vitamin E is a fat-soluble vitamin. Vitamin E has an important function as an antioxidant. As such, it prevents the degradation of polyunsaturated fat and other compounds by oxygen. Vitamin E can be found in different forms known as tocopherols or tocotrienols. Although there is some variation in their biological activity, about 1 milligram vitamin E is equivalent to 1 international unit (IU). Food sources: Good sources of vitamin E include vegetable oils, wheat germ oil, seeds, nuts, and soy beans. Other adequate sources are leafy greens, brussels sprouts, whole wheat products, whole grain breads and cereals, avocados, spinach, and asparagus. Vitamin K Vitamin K cannot be made by our bodies, but not all vitamin K needs to be obtained from food, because bacteria in our gut can make it . Newborn babies can sometimes suffer vitamin K deficiency, as can people who do not absorb fat, since vitamin K is fat soluble. Food sources: Best sources are spinach, salad greens, broccoli, brussel sprouts and cabbage. Most individuals can acquire the necessary amount of vitamin K from their diet. But, since vitamin K2 is also synthesized in the intestines, humans are not dependent upon food for this nutrient.

Thiamin Vitamin B1 Thiamin is a water soluble vitamin. One of the most significant losses of thiamin from food occurs in the milling of cereals. It can also be destroyed by heating and is sensitive to air or oxygen and also to alkaline conditions. In addition, alcohol can reduce the availability of thiamin to the body. For these various reasons, in both developing and developed countries, thiamin deficiency can be a problem. Thiamin is involved in the action of certain enzymes in the body, especially one that enables carbohydrate to be used as energy. Thus, with thiamin deficiency, a number of important body functions can be disturbed. They include brain function, nerve function (especially of the legs),

and heart function; these three impairments are called Wernicke-Korsakoffs psychosis', dry beri-beri and wet beri-beri, respectively. Food sources: All plant and animal foods contain vitamin B1, but only in small concentrations. The richest sources are yeast and organ meats. Whole cereal grains comprise the most important dietary source of vitamin B1 in human diets. Riboflavin Vitamin B2 Riboflavin can be destroyed by the action of ultraviolet radiation in sunlight. A particularly important loss of this vitamin can occur in product packed in clear containers when they are exposed to sunlight. Riboflavin deficiency results in inflammation of the tongue and lips and also cracking and dryness of the lips and corner of the mouth and other symptoms. Riboflavin deficiency in children causes growth retardation. Inadequate intakes of riboflavin would normally be associated with a deficiency of other B-group vitamins, which would result in multiple problems. Food sources: The best sources of vitamin B2 are liver, milk, and dairy products. Moderate sources include meats, dark green vegetables, eggs, avocados, oysters, mushrooms, and fish (especially salmon and tuna). Niacin Niacin can be obtained from food or made in our bodies from the amino acid, tryptophan. Tryptophan is a constituent of protein, although not all proteins are good sources of tryptophan. Not all niacin in food may be equally available to the body, because some is rather tightly bound to other food constituents and not easily released. Those at particular risk of niacin deficiency are those whose diets consist of mainly corn, which is low in both tryptophan and niacin, and alcohol abusers. Pellagra is a condition resulting from niacin deficiency, in which there are symptoms of dermatitis in skin exposed to the sun, diarrhoea and dementia. With lesser degrees of deficiency, general weakness, loss of appetite and indigestion can occur, but these symptoms can also occur in many other circumstances. Food sources: both niacin and its precursor (tryptophan) are included when determining the niacin content of foods. Lean meats, poultry, fish, and peanuts are good sources of both niacin and tryptophan. Organ meats, brewer's yeast, milk, legumes, peanuts, and peanut butter are the best sources of niacin. Niacin, like other B vitamins, is also synthesized by intestinal bacteria. Folic acid Folic acid is present in many forms in food. It is sometimes referred to as folate.

The availability to the body of folic acid in food depends not only on the form, but also on other food properties, such as acidity, the amount of dietary fiber and the amount of carbohydrate. Folic acid is sensitive to heat, to air or oxygen and to alkaline conditions. Folic acid, like vitamin B-12, is involved in the formation of the genetic material of newly forming cells and in protein formation. The consequences of deficiency include anaemia and defective lining of the gut, adversely affecting absorption of many nutrients. Since the number of blood platelets (which play a part in blood clotting) can be low with folic acid deficiency, a tendency to prolonged bleeding can also occur. Those at risk from folic acid deficiency include pregnant women as folic acid is important for a healthy formation of the future baby neural tube. Food sources: Folic acid is found in a wide variety of foods. Best sources include dark green leafy vegetables, brewer's yeast, liver, and eggs. Other good sources are beets, broccoli, brussels sprouts, orange juice, cabbage, cauliflower, cantaloupe, kidney and lima beans, wheat germ, and whole grain cereals and breads. The "friendly" intestinal bacteria also synthesize folic acid. Pyridoxin Vitamin B6 They are different forms of the vitamin, but they have the same function in our bodies. The forms of vitamin B-6 found in food are pyridoxine, mainly in vegetables, and pyridoxal and pyridoxamine, mainly in foods from animal sources. Vitamin B-6 is sensitive to light, air or oxygen and to alkaline conditions. Vitamin B-6 is involved in the functioning of some enzymes (natural substances that speed up chemical reactions), especially those involved in protein metabolism, the formation of chemicals for transmission of impulses in brain and nerves, and in red blood cell formation. With early deficiency of vitamin B-6, ill-defined symptoms such as sleeplessness, irritability and weakness may occur, but, their presence may be for other reasons. A big vitamin B-6 deficiency may lead to depression, convulsions, abnormal nerve functions (especially in the limbs), dermatitis, cracking of skin at the corner of the mouth and the lips, a smooth tongue, and anaemia. Food sources: The best sources of pyridoxine are yeast, wheat germ, organ meats (especially liver), peanuts, legumes, potatoes, and bananas. The normal flora in the human intestinal tract also synthesize vitamin B6 Vitamin B12 Animals ultimately acquire vitamin B-12 from micro-organisms; people eating animal products are unlikely to suffer any deficiency. People in traditional vegetarian cultures probably

obtained most of their vitamin B-12 through microbial contamination of food. Small amounts may also be obtained from water through its association with soil micro-organisms, and from bacteria normally living in the mouth. With newer, more hygienic practices, vitamin B-12 deficiency sometimes now occurs in people on a vegetarian diet, especially the infants of vegetarian mothers. One reason why vitamin B-12 deficiency is rare is that the liver stores in our bodies can last for as long as 5 years or more. Vitamin B-12 is not sensitive to heat, light, air or oxygen, but can be destroyed by alkaline conditions. Vitamin B-12 and folic acid are involved together in the formation of the genetic material in the nuclei of body cells (DNA), and in the formation of RNA, which is another important chemical involved in protein synthesis. The main features of vitamin B-12 deficiency are anaemia and disordered function of the central nervous system. A condition called pernicious anaemia results from an inability to absorb vitamin B-12 rather than through dietary deficiency. Hence, in this condition, vitamin B-12 injections are given. Food sources: Vitamin B12 is produced by microbial synthesis in the digestive tract of animals. Hence, animal protein products are the source of this nutrient. It does not occur in fruits, vegetables, grain, or legumes. Organ meats are the best source of vitamin B12, followed by clams, oysters, beef, eggs, milk, chicken, and cheese. Vitamin C Vitamin C is a water soluble vitamin and serves a number of essential metabolic functions. It also assists in absorption of non-haem iron and is an important anti-oxidant. Probably the first disease to be recognized as being caused by a nutritional deficiency was scurvy, when it was found that certain foods could prevent the disease. Scurvy was described by the Egyptians and Greeks, but it was Bachstrom in Leiden in 1734 who maintained that it was due to a lack of fresh vegetables in the diet. In 1795, the British Admiralty adopted James Lind's recommendations for citrus fruit (orange, lemon, lime) to prevent seaboard scurvy and, thereafter, British sailors were nicknamed 'limeys'. In scurvy, the connective tissues of the body are defective; the tissues are fragile, and bleeding occurs into the skin, from the gums and into deeper tissues. Wound healing is also poor. Changes in brain and nerve function occur, with mood and personality changes. Muscle weakness and proneness to infection may occur. Our bodies' ability to detoxify certain chemicals may also be reduced in scurvy. It seems likely that there may be lesser degrees of vitamin C deficiency than the extreme of scurvy. Vitamin C (or ascorbic acid, as it is also called) can be lost from foods because of its water solubility, and sensitivity to heat, air or oxygen. The addition of alkalis, such as sodium bicarbonate, can destroy it.

People at risk from vitamin C deficiency include those who avoid fruit and vegetables, those who have no access to fruit and vegetable (mountainous area during winter period), those with poor cooking practices, and the elderly. Food source: The best sources of vitamin C are fresh fruits, especially citrus fruits, strawberries, cantaloupe and currants, and fresh vegetables, especially Brussels sprouts, collard greens, lettuce, cabbage, peas, and asparagus.

Vitamin A

retinol Conversion units: 1 mcg RE (microgram Retinol Equivalent) = 3.33 IU (International Units) = 2 mcg beta carotene

Vitamin D

D2: ergocalciferol D3: choleclciferol Conversion units: 1 mcg = 40 IU (International Units)

Vitamin E

alpha, beta, gamma tocopherols and alpha tocotrienol Conversion units: 1 mg AT (milligram alpha-tocopherol) = 1.49 IU (International Units)

Vitamin K

K1: phylloquinone, phytomenadione K2: farnoquinone, menaquinone K3: menadione

Vitamin B1

Thiamin

Vitamin B2

Riboflavin

Vitamin B6

Pyridoxal, pyridoxine, pyridoxamine

Vitamin B12

Cobalamins, cyanocobalamin, hydroxocobalamin

Niacin

Nicotinic acid (vitamin PP) Niacinamide, nicotinamide

Folic acid

Folacin (vitamin M)

Biotin

Vitamin H

Vitamin C

Ascorbic acid

You can navigate to the following from here:

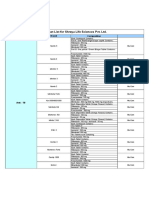

Recommended Nutrient Intakes - RNI Minerals & Vitamins [WHO/FAO - 2002] Upper tolerable nutrient level - UL [Food and Nutrition Bulletin - 2004]

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Assignment No 13a PDFDocumento4 pagineAssignment No 13a PDFFaisal IzharNessuna valutazione finora

- BIOLOGY RESEARCH Vitamin C 10th GradeDocumento5 pagineBIOLOGY RESEARCH Vitamin C 10th Gradep7qqg7mc7bNessuna valutazione finora

- Vital Vitamins: Harnessing Nature's Power for Optimal Health and WellbeingDa EverandVital Vitamins: Harnessing Nature's Power for Optimal Health and WellbeingNessuna valutazione finora

- Middle Aged WomenDocumento36 pagineMiddle Aged WomenVianz ChungNessuna valutazione finora

- Curs Nutritie Rezumat - Part 2Documento7 pagineCurs Nutritie Rezumat - Part 2Leordean VeronicaNessuna valutazione finora

- Caused MalnutritionDocumento6 pagineCaused MalnutritionMUHAMMAD HASEEBNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamin For SeniorsDocumento7 pagineVitamin For SeniorsLiving MaplesNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamin&minerDocumento10 pagineVitamin&minerChandu SekharNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamins: Vitamin ADocumento4 pagineVitamins: Vitamin Aamicho2407Nessuna valutazione finora

- What Is A Nutritional DeficiencyDocumento32 pagineWhat Is A Nutritional DeficiencyErica BorlagdanNessuna valutazione finora

- Nutrition AssignmentDocumento2 pagineNutrition AssignmentRoy MutahiNessuna valutazione finora

- Iron: An Essential Nutrient: RequirementDocumento3 pagineIron: An Essential Nutrient: Requirementiuzizuz8uzzzzNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamin B1 Facts.: Cardiovascular DiseaseDocumento5 pagineVitamin B1 Facts.: Cardiovascular DiseaseGurvinderpal SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Balanced DietDocumento4 pagineBalanced DietThe CSS PointNessuna valutazione finora

- ShanDocumento4 pagineShanJhan Rhoan SalazarNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are Micronutrients PDFDocumento2 pagineWhat Are Micronutrients PDFelvis prestlyNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are Micronutrients PDFDocumento2 pagineWhat Are Micronutrients PDFLakshmi Srinivasa EnterprisesNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are Micronutrients PDFDocumento2 pagineWhat Are Micronutrients PDFJishan AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Iron Deficiency Anaemia in Toddlers: Learning PointsDocumento8 pagineIron Deficiency Anaemia in Toddlers: Learning PointsAfiqah So JasmiNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiple Micronutrients: Elements) Adalah Mineral Yang Dibutuhkan Tubuh Dalam Jumlah Kurang Dari 100 MGDocumento7 pagineMultiple Micronutrients: Elements) Adalah Mineral Yang Dibutuhkan Tubuh Dalam Jumlah Kurang Dari 100 MGEvylina TambunanNessuna valutazione finora

- Micronutrient Vitamin and Mineral TumbangDocumento40 pagineMicronutrient Vitamin and Mineral Tumbangpujipoe85Nessuna valutazione finora

- Iron Deficiency AnemiaDocumento16 pagineIron Deficiency AnemiaBibin Panicker100% (1)

- 2223 Level M Biology Course Questions - Solutions UpdatedDocumento129 pagine2223 Level M Biology Course Questions - Solutions UpdatedFreddy BotrosNessuna valutazione finora

- Possible Cancer PreventionDocumento9 paginePossible Cancer Preventionanon_103184851Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1 - 7 - Focus On Minerals (13-53)Documento6 pagine1 - 7 - Focus On Minerals (13-53)chapincolNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 7Documento22 pagineChapter 7PaaKofi Amo BempahNessuna valutazione finora

- 4.1: Vitamins: Vital Dietary ComponentsDocumento11 pagine4.1: Vitamins: Vital Dietary ComponentsMAZIMA FRANKNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are Nutritional Deficiencies?: Doesn't Absorb Digestion Problems Skin Disorders DementiaDocumento7 pagineWhat Are Nutritional Deficiencies?: Doesn't Absorb Digestion Problems Skin Disorders DementiaRaef AhmedNessuna valutazione finora

- Fat Soluble VitaminDocumento41 pagineFat Soluble VitaminHusna AmalanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Food and Nutrition Inv ProjDocumento5 pagineFood and Nutrition Inv Projdeshchinar2007Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nutrition of The MusculoskeletalDocumento13 pagineNutrition of The MusculoskeletalnaytayNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamins (Lecture For Biochemistry)Documento12 pagineVitamins (Lecture For Biochemistry)MadsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Food Pyramid GuideDocumento5 pagineThe Food Pyramid GuideSamantha Dayne FernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Balanced DietDocumento10 pagineBalanced DietMsKhan0078100% (1)

- The Hidden Deficiency Uncovering the Health Impacts of Mineral ShortagesDa EverandThe Hidden Deficiency Uncovering the Health Impacts of Mineral ShortagesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pocket Guide to Vitamins: An accessible, handy guide to vitamins and other supplementsDa EverandThe Pocket Guide to Vitamins: An accessible, handy guide to vitamins and other supplementsNessuna valutazione finora

- Healty DietDocumento11 pagineHealty DietmarkoNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamins and MineralsDocumento2 pagineVitamins and MineralsMargaret Isabel LacdaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 3 Assignment:-Vitamin and Minerals and Water Oh My! by Ram GazmerDocumento3 pagineWeek 3 Assignment:-Vitamin and Minerals and Water Oh My! by Ram GazmerramNessuna valutazione finora

- Deficiency DiseasesDocumento5 pagineDeficiency DiseasesNandiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Eaxm Cheat Sheet Intro To NutritionDocumento3 pagineFinal Eaxm Cheat Sheet Intro To NutritionKeyasia BaldwinNessuna valutazione finora

- Digestive Issues and Nutrient Deficiences: Science 8 - 4th QuarterDocumento24 pagineDigestive Issues and Nutrient Deficiences: Science 8 - 4th QuarterjericNessuna valutazione finora

- Biology Level M Couse Questions SolutionDocumento71 pagineBiology Level M Couse Questions SolutionMyNameIsYeetNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamins: A Step By Step Guide for Men Live A Supplement – Rich Lifestyle!Da EverandVitamins: A Step By Step Guide for Men Live A Supplement – Rich Lifestyle!Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nutrition: Vitamins and Minerals: The most important information you need to improve your healthDa EverandNutrition: Vitamins and Minerals: The most important information you need to improve your healthNessuna valutazione finora

- Diet Nutrition and FitnessDocumento5 pagineDiet Nutrition and Fitnesscagadas.checheNessuna valutazione finora

- 2324 Level M (Gr11 UAE - GULF) Biology Course Questions SolutionsDocumento111 pagine2324 Level M (Gr11 UAE - GULF) Biology Course Questions SolutionsVan halenNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Vitamin DDocumento4 pagineWhat Is Vitamin DswamysrinivasNessuna valutazione finora

- Macro and Micro Minerals-1Documento38 pagineMacro and Micro Minerals-1Ximay Mato100% (1)

- Rickets - A Brief View With Homoeopathic ApproachDocumento32 pagineRickets - A Brief View With Homoeopathic ApproachDr. Sandeep Anwane100% (1)

- Macro and Micro Minerals-1-1Documento36 pagineMacro and Micro Minerals-1-1pinkish7_preciousNessuna valutazione finora

- Karnataka Tourism Policy 2015 - 20Documento7 pagineKarnataka Tourism Policy 2015 - 20Somya MehndirattaNessuna valutazione finora

- EnzymesDocumento38 pagineEnzymesSomya Mehndiratta100% (1)

- Westfalia in Palm Oil MillDocumento24 pagineWestfalia in Palm Oil MillSupatmono NAINessuna valutazione finora

- Voluntary Food LawsDocumento9 pagineVoluntary Food LawsSomya Mehndiratta100% (1)

- Orange Peel Perfume As An Alternative Fragrant ParaphernaliaDocumento2 pagineOrange Peel Perfume As An Alternative Fragrant ParaphernaliaLaurenz AlkuinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Degenerative Myelopathy of German ShepherdsDocumento11 pagineDegenerative Myelopathy of German ShepherdsMonty001Nessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of Lactic Acid Fermentation On The Retention of Beta-Carotene Content in Orange Fleshed Sweet PotatoesDocumento21 pagineEffects of Lactic Acid Fermentation On The Retention of Beta-Carotene Content in Orange Fleshed Sweet PotatoesLa Ode SyaharuddinNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemistry Project - BilalDocumento6 pagineChemistry Project - Bilalmetrotigers377Nessuna valutazione finora

- Aonla: Aonla (Emblica Officinalis) or Indian Gooseberry Is Indigenous To Indian Sub-Continent. India Ranks First inDocumento21 pagineAonla: Aonla (Emblica Officinalis) or Indian Gooseberry Is Indigenous To Indian Sub-Continent. India Ranks First inphani kumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Product List For Shreya Life Sciences Pvt. LTD.: Segment Brand CompositionDocumento8 pagineProduct List For Shreya Life Sciences Pvt. LTD.: Segment Brand CompositionYadwinder SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Characteristics of Cemcem (Spondiaz Pinnata L.F. Kurz) Instant PowderDocumento14 pagineCharacteristics of Cemcem (Spondiaz Pinnata L.F. Kurz) Instant Powdersgd 2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Toyosi Vit C PresentationDocumento21 pagineToyosi Vit C PresentationOlayide Israel RobinsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Nivee Amla JuiceDocumento1 paginaNivee Amla JuiceKarthik SachidanandaNessuna valutazione finora

- 39 Prep GuideDocumento73 pagine39 Prep Guidedaljit chahalNessuna valutazione finora

- MCQ Vitamins BiochemistryDocumento16 pagineMCQ Vitamins BiochemistryNOOR100% (6)

- DR Axe Collagen HacksDocumento15 pagineDR Axe Collagen HacksNeag AlinNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 - Vitamin CDocumento12 pagine3 - Vitamin CskyeandoNessuna valutazione finora

- All ProductTraning Guide - EnglishDocumento44 pagineAll ProductTraning Guide - EnglishSunil Sharma75% (4)

- Validation of A HPLC Method For Simultaneous Determination of Main Organic Acids in Fruits and Juices PDFDocumento5 pagineValidation of A HPLC Method For Simultaneous Determination of Main Organic Acids in Fruits and Juices PDFsara_tabares_2Nessuna valutazione finora

- E-Marking Notes On Chemistry SSC II May 2018Documento23 pagineE-Marking Notes On Chemistry SSC II May 2018MAQ Daring GamerNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamins To CLEAN Your FATTY LIVERDocumento5 pagineVitamins To CLEAN Your FATTY LIVERNiloufar GholamipourNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamin CDocumento178 pagineVitamin CcinthiaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1jee Soci enDocumento42 pagine1jee Soci enRahayuJaranImoetYukikoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemical Changes During Extrusion Cooking - Camire PDFDocumento13 pagineChemical Changes During Extrusion Cooking - Camire PDFmarmaduke32Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 50 Multiple-Choice Questions - NDocumento6 pagineChapter 50 Multiple-Choice Questions - NVincent haNessuna valutazione finora

- Anemia - PPT PresentationDocumento23 pagineAnemia - PPT PresentationRommel Montero RicioNessuna valutazione finora

- Arnon, D. I. 1949. Copper Enzymes in Isolated ChloroplastsDocumento16 pagineArnon, D. I. 1949. Copper Enzymes in Isolated ChloroplastsSagara7777Nessuna valutazione finora

- Natural Bioactive Compounds of Citrus Limon For Food and Health PDFDocumento19 pagineNatural Bioactive Compounds of Citrus Limon For Food and Health PDFEsteban Davila100% (1)

- Entrepreneurship Project of New Product LaunchingDocumento52 pagineEntrepreneurship Project of New Product LaunchingDhannu Rawani50% (2)

- Herbalife PDFDocumento64 pagineHerbalife PDFZINAKHONessuna valutazione finora

- 12 Health Healing FoodsDocumento10 pagine12 Health Healing FoodsBahukhandiNessuna valutazione finora

- Vitamin B12 Boots Energy and Cures FatigueDocumento9 pagineVitamin B12 Boots Energy and Cures FatiguecantodelcisneNessuna valutazione finora

- ProjectDocumento21 pagineProjectAanchal SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nutri QuizDocumento108 pagineNutri QuizAxel RoveloNessuna valutazione finora