Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Women in India Have Been Experiencing Different Status

Caricato da

Asif EkramDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Women in India Have Been Experiencing Different Status

Caricato da

Asif EkramCopyright:

Formati disponibili

---------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------Drain of Wealth during British Raj Whenever the issue of economic exploitation and the drain

of wealth during the 200 years of British colonial rule comes up, the one rebuttal from western historians is that there is scant evidence to prove it. To bolster the argument, the point is then made that Indian historians are nationalist, biased (sometimes as a consequence) and do not pay attention to figures and statistical evidence. In my analysis of this topic, I have therefore, relied heavily on recent research by Western historians and tried to draw conclusions based on that. Even by the accounts of western historians, the positive impact of British rule, which PM Sh. Man Mohan Singh had so pointedly mentioned during his speech at Oxford in Jul 05, is questionable. The drain of wealth from India to Britain during the two centuries of colonial rule was very real, very substantial and there are strong reasons to believe that India may have looked significantly different (and far better) economically and socially had it not been for the two centuries of British rule. The beginning of this period can probably be traced back to the Battle of Plasssey. As Prof. Richards writes in the introduction to his paper Imperial Finance Under the East India Company 1762 -1859*i+, On June 23,1757, Robert Clive, commanding a small force of East India Company professional troops, defeated and killed Siraju-uddaula, the ruling Nawab of Bengal, on the battlefield of Plassey. The battle marked a significant turning point in world history, for it permitted the English East India Company to gain control over the rich resources of the Mughal successor state in northeastern Bengal and Bihar. This was the starting point for a century-long process of British conquest and dominion over the entire Indian subcontinent and beyond. To help grasp the full extent of this exploitation, I have split my analysis into five parts. In Part 1, I look at the tax regime and the burden of administrative machinery. In Part 2, I try to get behind the assertion that the British contributed much to the improvement of education and public works in India. In Parts 3 and 4, I look at unfair trade practices and the drain of wealth. In the final part, I have tried to summarize the impact of these 200 years of servitude. TAXES & ADMINISTRATIVE BURDEN In their recent research on deindustrialization in India[ii], Profs Williamson and Clingingsmith mention that while the maximum revenue extracted by the Mughals as high as 40%, this paled in comparison to the effective tax rate in the early years of colonial rule: as central Mughal authority waned, the state resorted increasingly to revenue farming(raising) the effective rent share to 50% or more Further, There is no reason to believe that when the British became rulers of the su ccessor states the revenue burden declined (pg 7). After initial attempts at revenue farming, Company officials aggressively introduced new taxes in an attempt to reduce their dependence on agrarian production, thus worsening the tax burden on the common man. As Prof Richards points out in his paper (Ref 1), Land revenue continued to be the mainstay of the regime until the end of British rule in India, but its share of gross revenues was far less than under the Mughal emperorsTo a larger degree, however, new taxes not imposed by the Mughals accounted for land revenues declining share. Company officials began early to diversify their tax base so that the new regime was not so overwhelmingly dependent upon agrarian production. In his research on the subject, Prof Maddison[iii] mentions the burden imposed by the administrative machinery of the State: British salaries were high: the Viceroy received 25,000 a year, and governors 10,000From 1757 to 1919, India also had to meet administrative expenses in London, first of the East India Company, and then of the India Office, as well as other minor but irritatingly extraneous charges. The cost of British staff was raised by long home leave in the UK, early retirement and lavish amenities in the form of subsidized housing, utilities, rest houses, etc. Prof. Richards mentions that although the Company raised their revenue demands in each territory to the highest assessments made by previous Indian regimes they were still insufficient to meet the comb ined administrative, military and commercial expenses of the Company ******** SPENDING ON EDUCATION & PUBLIC WORKS Although there is a prevalent myth around British contribution to development if education and infrastructure in India, in reality, the situation was quite different. Prof Maddison writes that as late as 1936, the bulk of government expenditure was focused more on ensuring the stability of the empire than anything else: Even in 1936, more than half of government spending was for the military, justice, police and jails, and less than 3 per cent for agriculture (pg 4) Amidst all the paraphernalia of the Raj, public works and social expenditure was completely forgotten. As Prof. Richards notesthe Company allocated negligible funds for public works, for cultural patronage, for charitable relief, or for any form of education.(confining) its generosity to paying extremely high salaries to its civil servants and military officers. Otherwise parsimony ruled. The following excerpt from Prof Maddisons essay squarely debunks the notion that the British did a lot for education and were conscious of the wealth of ancient knowledge some of which was still extant at the time.

The contempt that Macaulay felt towards the knowledge and wisdom of ancient Hindus is evident from this quote: We are a Board for wasting public money, for printing books which are less value than the paper on which they are printed was while it was blank; for giving artificial encouragement to absurd history, absurd metaphysics, absurd physics, absurd theology ... I have no knowledge of either Sanskrit or Arabic ... But I have done what I could to form a correct estimate of their value ... Who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia ... all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanskrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgements used at preparatory schools in E ngland. (pg 5) Unsurprisingly, (pg 6) The education system which developed was a very pale reflection of that in the UK. Three universities were set up in 1857 in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay, but they were merely examining bodies and did no teaching. Drop-out ratios were always very high. They did little to promote analytic capacity or independent thinking and produced a group of graduates with a half-baked knowledge of English, but sufficiently Westernized to be alienated from their own culture. the great mass of the population had no access to education and, at independence in 1947, 88 per cent were illiterate at independence only a fifth of children were receiving any primary schooling. Education was used as a tool to turn a tiny elite into imitation Englishmen and a somewhat bigger group into government clerks. If we turn our eyes to other areas of development, the picture does not improve. In spite of agriculture being - by far - the most significant part of the economy, Little was done to promote agricultural technology. There was some improvement in seeds, but no extension service, no improvement in livestock and no official encouragement to use fertilizer. Lord Mayo, the Governor General, said in 1870, I do not know what is precisely meant by ammoniac manure. If it means guano, superphosphate or any other artificial product of that kind, we might as well ask the people of India to manure their ground with champagne (Pg 11). In his analysis of the various charges and expenses that the Company incurred, Professor Richards mentions how Company officials were extremely wary of any public works spending uinless it was for projects of direct use to the state. The following sentences are instructive and effectively blast the myth that the British did lasting good by building modern infrastructure in India: The Company even failed to repair and maintain roads, river embankments, and bunded storage tanks for irrigation that had been the responsibility of earlier regimes. When, in 1823, the Governor General in Council decided to devote a portion of anticipated surplus revenues to works of public improvement, the Court of Directors rejected this proposal. When, the Directors learned of heavy expenditures on buildings in the mid 1820s, they wrote to the Governor General to condemn this extravagance. ******** MONOPOLY & UNFAIR TRADE PRACTICES To comprehend the extent of unfair trade norms, ju st one example would suffice (excerpted from this excellent essay: The Colonial Legacy - Myths and Popular Beliefs*iv+) As early as 1812, an East India Company Report had stated "The importance of that immense empire to this country is rather to be estimated by the great annual addition it makes to the wealth and capital of the Kingdom....." Few would doubt that Indo-British trade may have been unfair - but it may be noteworthy to see how unfair. In the early 1800s imports of Indian cotton and silk goods faced duties of 70-80%. British imports faced duties of 24%! As a result, British imports of cotton manufactures into India increased by a factor of 50, and Indian exports dropped to one-fourth! A similar trend was noted in silk goods, woollens, iron, pottery, glassware and papermillions of ruined artisans and craftsmen, spinners, weavers, potters, smelters and smiths were rendered jobless and had to become landless agricultural workers. The monopoly on trade in salt and opium was an important mainstay of the Companys finances. Prof. Richards notes that Together opium and salt produced on average 18.9 percent of gross revenues. In last fifteen years of Company rule their share climbed to 25.1 percent, as opium became one of the most valuable commodities sold in world commerce. Prof. Richards has noted Edmund Burkes report that accompanied the Select Committee of Parliament meetings in 1782-1783 to investigate the Companys affairs. To quote Edmund Burke: But at, or very soon after, the Acquisition of the Territorial Revenues to the English Companya very great Revolution took place in Commerce as well as in Dominion;.From that Time Bullion was no longer regularly exported by the English East India Company to Bengal, or any part of Hindustan;. A new Way of supplying the Market of Europe by means of the British Power and Influence, was invented; a Species of Trade (if such it may be called) by which it is absolutely impossible that India should not be radically and irretrievably ruined. This is how the pernicious system worked: A certain Portion of the Revenues of Bengal has been for many Years set apart, to be employed in the Purchase of Good for Exportation to England, and this is called The Investment, The Greatness of this investment has been the standard by which the merit of the Companys Principal Servants has been generally estimated; and this main Cause of the Impoverishment of India has generally been taken as a Measure of its Wealth and Prosperity.

This Export from India seemed to imply also a reciprocal Supply, which the Trading Capital employed in these Productions was continually strengthened and enlarged. But the Payment of a Tribute, and not a beneficial Commerce to that Country, wore this specious and delusive Appearance. ******** THE DRAIN OF WEALTH However, the high taxes, the heavy burden of state, the neglect of education and public works and unfair trade practices these were only the tip of the iceberg. The most damning evidence of British exploitation was the irrefuta ble drain of wealth that took place over the period of two centuries. Prof. Williamson and Clingingsmith have noted that between 1772 and 1815 there was a huge net financial transfer from India to Britain in the form of Indian goods. The drain resulti ng from contact with the West was the excess of exports from India for which there was no equivalent import included a bewildering variety of cotton goods for re-export or domestic [consumption], and the superior grade of saltpeter that gave British cannon an edge Javier Cuenca Esteban estimates these net financial transfers from India to Britain reached a peak of 1,014,000 annually in 1784-1792 before declining to 477,000 in 1808-1815 (Pg 9). However even this high figures are significantly lower than the estimates by Prof John Richards (cited later in this essay). Like all other commentators, Maddison too has mentioned the debilitating effect of the drain of funds from India: Another important effect of foreign rule on the long-run growth potential of the economy was the fact that a large part of its potential savings were siphoned abroad. This 'drain' of funds from India to the UK has been a point of major controversy between Indian nationalist historians and defenders of the British raj. However, the only real grounds for controversy are statistical. There can be no denial that there was a substantial outflow which lasted for 190 years. If these funds had been invested in India they could have made a significant contribution to raising income levels. (Pg 20) The total drain due to government pensions and leave payments, interest on nonrailway official debt, private remittances for education and savings, and a third commercial profits amounted to about 1.5 per cent of national income of undivided India from 1921 to 1938 and was probably a little larger before that about a quarter of Indian savings were transferred out of the economy, and foreign exchange was lost which could have paid for imports of capital goods. Separately, Dadabhai Naoroji estimated the economic costs and drain of resources from India to be at least at 12m per annum. Here is an extract from one of his essays, The Benefits of British Rule*v+, 1871 Financially: All attention is engrossed in devising new modes of tax ation, without any adequate effort to increase the means of the people to pay; and the consequent vexation and oppressiveness of the taxes imposed, imperial and local. Inequitable financial relations between England and India, i.e., the political debt of ,100,000,000 clapped on India's shoulders, and all home charges also Materially: The political drain, up to this time, from India to England, of above ,500,000,000, at the lowest computation, in principal aloneThe further continuation of this drain at the rate, at present, of above ,12,000,000 per annum, with a tendency to increase. Prof. Richards mentions in his research that: Between 1757 and 1859 .Officials of the East India Company tapped the productive people and resources of Bengal and the eastern Gangetic valley to fund the protracted military campaigns necessary to conquer India. Over the same century, these same resources also supplied the wherewithal for a century-long transfer of wealth from India to Great Britain. Burke estimated that in the four years ending in 1780 the investment averaged no less th an one million sterling and commonly Nearer Twelve hundred thousand pounds. This was the value of the goods sent to Europe for which no Satisfaction is made. The transfer continued without interruption and with formal approval from Parliament. In 1793, this devious system of extortion was given official sanction and thus was paved the path to financial ruin: By this 1793 Parliamentary directive, the Company was enjoined to take ten million current rupees (1 million sterling) each year for the investment from the territorial revenues of colonial India. After 1793, the Company zealously maintained its annual investments. Between 1794 and 1810, the average annual cost of the investment was 1.4 million sterling. In a recent contribution, Javier Cuenca Esteban puts the arguably minimum transfers from India to Britain between 1757 and 1815, Plassey and Waterloo, at 30.2 million sterling. This figure is the estimate of exports from which there was no compensating import for India. Post 1833, when the Companys commercial operations ceased, the drain took the form of Home Charges which represented the expenses in Britain borne by the Indian treasury. These Home Charges were a huge burden on the finances and contributed to a sustained and conti nuous deficit in the budget throughout the 19th century. As Prof Richards notes, (pg 17) there were few years in which the Indian budget was not in deficit. For the entire period (1815 1859), deficits reached a cumulative total of 76.9 million sterling or an annual average of 1.7 million sterling.

This systematic drain was nothing short of a loot albeit carried over 200 years and under the cover of colonial trade. It left the economy in shambles and reduce this great country from one of the powerhouses of the world economy to a laggard which was barely able to sustain itself. ******** THE IMPACT The collective impact of these policies and system of exploitation was severe. In their preface to the research, Profs. Clingingsmith and Williamson have this to say: India was a major player in the world export market for textiles in the early 18th century, but by the middle of the 19th century it had lost all of its export market and much of its domestic marketWhile India produced about 25 percent of wo rld industrial output in 1750, this figure had fallen to only 2 percent by 1900. This table eloquently depicts the impact of almost two centuries of British colonial rule over India ----************************************************************************ Forest Policy and Tribal Development In 1974-1975, about 22 percent of India's total geographical area was covered by forests. This forest region, interspersed all over the country, consists of evergreen forests, deciduous forests, dry forests, alpine forests, riparian forests and tidal forests. Some of these forests are conspicuous for their dense growth. Besides the commercially valuable sal, teak, ironwood, sandalwood and shisam, these forests are rich in the growth of climbers (epiphyte) and various kinds of minor forest produce. While the forest-based industries have relief on the commercially valuable wood, the forest dwellers, a majority of whom are Scheduled Tribes, have depended on the minor forest produce for their subsistence. According to the 1971 Census Report, a majority of the tribals lived in the countryside and relied mainly on agriculture. From an economic point of view, the tribes could be classified as semi-nomadic, the jhum cultivators and the settled cultivators, living completely on forest produce. Forests are the main source of subsistence for them. They collect their food from them; use the timber or bamboo to construct their houses; collect firewood for cooking and in winter to keep warm; use grass for fodder, brooms and mats; collect leaves for leaf plates; and use harre behra for dyeing and tanning. The forest regions are also inhabited by non-tribals, who depend on forests for fuel, fodder and so on. This article will try to assess the nature and extent of forest dwellers' dependence on forests. To what extent does the forest policy implemented by different states and Union territories ensure that the basic needs of forest dwellers are met? How does the forest policy seek to improve the socioeconomic conditions of the forest dwellers? Forest Policy Before 1865, forest dwellers were completely free to exploit the forest wealth. Then, on 3 August 1865, the British rulers, on the basis of the report of the then-superintendent of forests in Burma, issued a memorandum providing guidelines restricting the rights of forest dwellers to conserve the forests. This was further modified in 1894. It stated that The sole object with which State forests are administered is the public benefit. In some cases the public to be benefited is the whole body of tax payers; in others the people on the track within which the forest is situated; but in almost all cases the constitution and preservation of a forest involve, in greater or lesser degree, the regulation of rights and restriction of privileges of users in the forest areas which may have previously been enjoyed by the inhabitants of its immediate neighborhood. This regulation and restrictions are justified only when the advantage to be gained by the public is great and the cardinal principle to be observed is that the rights and privileges of individuals must be limited otherwise than for their own benefit, only in such degree as is absolutely necessary to secure that advantage. In actual practice, however, all these pious declarations were set aside whenever they came in the way of British interests. For example, forests in Nagaland and the Terai were unscrupulously cut to meet the increasing demand of wood during both world wars. The National Forest Policy of the Government of India (1952) is an extension of this policy. This policy prescribed that the claims of communities near forests should not override the national interests, that in no event can the forest dwellers use the forest wealth at the cost of wider national interests, and that relinquishment of forest land for agriculture should be permitted only in very exceptional and essential cases. The old policy of relinquishing even valuable forests for permanent cultivation was discontinued and steps to use forest land for agricultural purposes were to be taken only after very serious consideration. To ensure the balanced use of land, a detailed land capability survey was suggested. Conservation of wildlife was to be regularized. The tribals were to be weaned away from shifting cultivation. The concept of "national interest" has been applied in a narrow sense. A welfare state cannot have a basic contradiction between local and national interests. As the analysis that follows will show, in the implementation of the forest policy, "national interests" remained confined to augmenting revenue earnings from the forests. Whenever the interests of the local people or ecological considerations hampered possible revenue from forests, the forest department pushed them aside on the pretext of broader national interest. Forest dwellers have been dissociated from the management and exploitation of forest wealth. The British contractual system that still exists in many states has resulted in unscrupulous exploitation of the local people and of the natural vegetation and wildlife that the forest policy was intended to conserve. Development programs construction of roads and availability of educational, medical and housing facilities - have allowed economically

viable outsiders to enter forest regions. In order to make quick profits, they have exploited the forest dwellers, displacing them from their land and making them bonded laborers. Except for the states of Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tripura, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Goa, Daman and Diu, the government has been earning huge net forest revenues. Over the years, this revenue has been increasing. On the other hand, except in a few places, the condition of the forest dwellers has been deteriorating. The government's various development programs and the tribal welfare schemes have by and large failed to make any dent in the deteriorating condition of the forests and forest dwellers. The crux of the problem lies in misdirected policy and its half-hearted implementation. Restrictions on Forest Dwellers The backbone of forest dwellers' economy is the vegetation found in the nearby forests. But the forest dwellers' rights to collect fuel, fodder and minor forest produce are very restricted. (In Arunachal Pradesh, the tribals have special rights to collect all forest produce and hunt and fish freely in all forests, whether reserved or unclassified. This concession is not found anywhere else). In almost all states, forest dwellers can collect forest produce, either free or at concessional rates, only from protected and unclassified forests. Even these are not legal rights, but are subject to various government restrictions and regulations. These facilities can even be terminated if the capacity of forests does not permit the exercise of the right. The right holders are also obligated to help the forest department prevent and fight forest fires and to help the staff in connection with forest offenses. In West Bengal, since Independence, forests have been the bone of contention between the forest department and the forest dwellers, most of whom are tribals. In forest dwellers contend that they, by virtue of being native people, have the right to use forest trees for their livelihood. One of their complaints is the cattle trenches dug around the forest areas prevent the free flow of water into their arable land. They were charged high rates for permits to collect minor forest produce, especially tussar cocoons. Grazing has been prohibited and their agricultural land has been recorded as forest land in the recorder of rights; later the tribals were asked to vacate the land. The forest department, on the other hand, blames the tribals for wanton and indiscriminate destruction of wilds vegetation and wildlife, sand urges the restriction of their rights over the forests. The tribal welfare department, while conceding the need to preserve the forest, says that the tribals do have special claims over the forests and forest produce. A government study team found the attitude of the forest department in many states to be one of callousness, indifference and neglect toward tribals. For example, the forest department in Karnataka (then Mysore), in its enthusiasm to set up a game sanctuary in the state, drove out the local inhabitants without making alternate arrangements for their resettlement. The intervention of the social welfare department was of no avail. The roads constructed in reserved forests by the social welfare department of the state for the benefit of the tribals, on the express understanding that they would be maintained by the forest department, have been badly neglected. The forest department must be persuaded with great difficulty to release water from tanks lying in reserved forests for irrigating the tribal areas lower down. In Andhra Pradesh, too, extensive areas under cultivation were being converted into reserved forests. The forest department has extended its boundaries almost to the doorstep of many tribal villages, instead of leaving open a strip, at least one kilometer in width, between the villages and the forest boundary. Areas were also included in the forests which had no tree growth at all and heavy fines were being imposed on tribal encroachers. In Tamil Nadu (then Madras), the study team found discrimination against tribals but not non-tribals in Wenlock Down. The latter were given land on pattas (land titles) either permanently or for long periods, but the Todas local inhabitants - received only annual cultivation permits. The study team also noted that extensive areas now classified as forests were under unauthorized cultivation. Without rights of ownership, the tribals could not undertake soil conservation measures. Moreover, the forest department's practice of serving eviction notices to tribal encroachers and fining them operated as a great hardship to the tribals. Finally, the study team observed that tree pattas, which entitle the holder to the use of the fruits of trees, were issued in Coimbatore district to non-tribals living far away from the tribal settlements, in respect to mango and tamarind trees in the tribal villages. O.P. Arya, in his interview with the officials of the forest department, voluntary agencies and forest dwellers, has tried to show the "bitter relationship between the forest administration and the local populace." The divisional forest officer he interviewed was "critical about the attitude of tribals toward the forest." His view was confirmed by the collector and the charge officer. On the other hand, the people - about 80 percent - complained during the field survey about harassment by the forest officials. The privileged ones, however, had good rapports with the forest department. The Irish missionary stationed in the area who, according to the author, gave "a very impartial view of the whole problem," said that "the forester used to take a lot of benefits from the tribals of the village. Some of them used to be employed in the forest and were paid much less than government rates. He used to take gifts in kind, too." Since the villagers depend solely on forests for their livelihood, the forester behaves like a ringmaster and makes them do what he desires. Exploitation of Forest Dwellers The various kinds of restrictions imposed on the forest dwellers virtually put them at the mercy of the forest department, especially lower-level functionaries. Illiteracy and poor economic conditions make them even more vulnerable. In some areas in Andhra Pradesh, the forest guards have their cut of minor forest produce earnings, and in some areas the tribals are often made to work without pay. In spire of the rest houses spread all over the block, the forest rangers or high level functionaries could not find it convenient to inspect the area. This is not an

isolated instance. The IAS probationers, during their survey of socioeconomic conditions of tribals in different states, noted different modes of exploitation by the forest guards and other lower-level functionaries who were invariably in league with the patwari and the local police constable. Forest dwellers have also become victims of the commercial exploitation of the forest. Since British rule, contractors have employed the forest dwellers to do unskilled jobs for low wages and in appalling conditions. In the late 1940s, Symington recommended the association of local inhabitants in the exploitation of forest produce. In 1946-1947, the Forest Labour Societies were initiated by B.G. Kher in the then Bombay state. The purpose of the Forest Labour Societies was "not only to give the Adivasi labourers full wages along with a share in the profit, but also to train them gradually to take up the responsibility of conducting forest and other business by their cooperative efforts." The Bombay state experiment was complemented in the First Five Year Plan. The Second Five Year Plan recommended the establishment of Forest Labour Societies in an increasing number in all states. It recognized that "the manner in which the forest resources are exploited has a great deal of bearing on their welfare. In many ways the penetration of forest contractor into tribal economy has been harmful" (Govt. of India 1956). The Third Five Year Plan stated that "development of forestry and forest industries is also essential for raising the income of the tribal people who live in the forest areas" (Govt. of India 1961). The Working Group of Welfare of Backward Classes for the Fourth Plan stated that the manner in which the existing forest policy is understood and implemented had placed the tribals completely at a disadvantage (Govt. of India 1967). The Resolution of the Central Board of Forestry reiterated replacing the contractors with Forest Labour Cooperatives. Gradually, the Forest Labour Cooperatives were set up in most of the states. But the contractual system of exploitation has not yet been rooted out. The Union Minister for Agriculture, Rao Birendra Singh, promised in the Parliament to end the contractual system of exploitation of forest wealth within three years. In fact, the forest dwellers' share as wage earners in cutting, logging and loading was significantly less than the ruling market price. The forest dwellers can gain from the forest wealth only when they are involved in its processing through cooperatives. The forest department also employs laborers for a variety of tasks such as road repair, road making and silviculture operations. Workers are also employed for departmental construction - building bridges, culverts and causeways. This gives much needed additional income to the tribals. With the expansion and development of forest-based industries, the demand for the exploitation of minor forest produce has increased. Unlike the major forest produce, minor forest produce in several states is collected by the government agencies and in others by businesspeople. Both the forest department and businesspeople are exploiters. In Madhya Pradesh, trade in tendu, patta, timber, gum, harra, bamboo, sal seeds and khair is nationalized. The payment of wages in the collection of tendu leaves is on the basis of number of bundles collected. The rate per bundle is different in the bordering states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. For example, when in Uttar Pradesh the rate was higher by 20 paise (US 20) per bundle, a person could not collect more than two bundles a day. Just to earn 40 paise (US 4c) more, the tendu leaf collectors in Madhya Pradesh used to walk 12-20 miles during the night and sell the bundles in Uttar Pradesh anon. In Orissa, the forest department has taken over the collection of tendu leaves. The forest region is classified into subdivisions and ranges. Each range has about 10 collection centers from which pluckers receive 10 paise (US 1c) for leaves. In this way the government earned annually Rs 44 million (US $3.4 million) or royalty, and the Forest Corporation a profit of Rs. 20 million (US $1.5 million). But this profit had been made at the cost of the tribals. Where the minor forest produce is not nationalized, businesspeople exploit the forest dwellers. In the Uttarakhand region in Uttar Pradesh, contractors employed local people at nominal wages, but made huge profits themselves. In Chamoli district the Dashauli Gram Swarajya Sangh intimidated the local people about the prevailing market prices of the different herbs and mushrooms they had collected, and advised them to sell their herbs rather than collect them at nominal wage for the contractor. Some tribal regions have no regular market. At the weekly mandis (marketplaces), private wholesale dealers buy the minor forest produce at very low rates and sell them at huge profits in the cities. Many times they pay the tribals in advance and later buy their goods at nominal costs. Since most of the tribals do not know how to count, the price that is promised often does not correspond to the amount they actually receive. Generally, the trader is a moneylender, too, who buys the produce from the tribals as repayment of a debt, but at incredibly low prices. The Tribal Development Corporations, Forest Corporations and some other cooperative agencies have taken up the sale of some produce, but the moneylender-cum-trader has yet to be eliminated by them. Development Programs and Forest Dwellers In the successive development programs for the forest regions, top priority is accorded to the development of transport and communication facilities so that education, health, land colonization, housing, development of horticulture, animal husbandry and cooperative schemes could be initiated in the region, bringing the forest dwellers into the mainstream of nation development. In actual practice, these priorities have brought non-tribal traders and settlers into the forest regions. These outsiders cheat the forest dwellers in the sale of forest produce, give them loans at exorbitant rates and then grab their land and turn them into bonded laborers. A pertinent comparison could be drawn between Manipur ant Tripura. In Manipur, as the study team noted, "there have hardly been any cases of transfer of land from tribals to non-tribals in the tribal areas." However, the team feared that "with the construction of roads and provision of adequate means of communication and the acceleration of development activities in the tribal areas, there is likely to be some pressure of non-tribals on the

tribals who will have to depend on the non-tribals for their daily needs of consumer goods and the like". In Tripura, on the contrary, the team noticed large-scale transfers of tribal land to non-tribals, with the result that the tribals were becoming landless and their economic condition was quickly deteriorating. The fruits of the development plans initiated by the central as well as the different state governments could not reach the local people, because these plans were not based on the perceived needs of the people. The study team, during its tour of various states, observed that development schemes failed because the planners did not take into account the stage of development of the tribes for whom the schemes were intended or the conditions in the areas where they were to be implemented. Another weak point in the development plans is the division between the general plans and special tribal development plans. Experience has shown that development plans in states such as Nagaland, Manipur and Arunachal, where they were meant for the tribals only, have had considerable le impact on the tribal economy. On the other hand, in provinces where the general programs were combined with tribal development programs, there is no conscious attempt to ensure that the tribals derive a reasonable share of benefit from the general development programs. Only the development programs meant for the Scheduled Tribes, which are in fact meant to supplement the benefits derived from development schemes under the General Sector, are treated as programs meant exclusively for the tribals. Huge amounts have been spent on land colonization schemes in different states. But because of bureaucratic red tape, inadequate facilities for land reclamation, soil conservation, the lack of irrigation facilities and job opportunities in the colonies, and the exploitation of tribals by go-betweens, these schemes have by and large failed. These colonies should be in line with the customs, habits, religious practices and beliefs of the forest dwellers. Otherwise as the experiment of the imposed development of the Veddas - a tribe of Sri Lanka - has shown, these various schemes would only worsen the condition of forest dwellers. In some states, where hydroelectric projects or mining operations have been set up, tribals are displaced on a large scale. Gujarat is the only state where the study team expressed satisfaction over the resettlement of the displaced people. On the other hand, in Bihar, in Singhblum and Ranchi districts, a large number of tribals were displaced to make way for heavy industries. In Rajasthan, the agricultural land of the forest dwellers was acquired by the government in the Udaipur and Durgapur regions to construct some irrigation and mining projects. As in Bihar, tribals were paid in cash for land, and they used it for nonproductive purposes. The study team suggested that the government take advance action to ascertain the extent of displacement of tribals, and draw up a comprehensive program for rehabilitating displaced families. In Orissa, Assam and Madhya Pradesh, tribals have been displace due to the reclamation of land in the tribal belt to resettle refugees from Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan). The governments of these states, in settling refugees, gave them certain facilities that were denied to the local people. For example, in resettling refugees under the Dandakaranya Project, refugees were given twice the compensation as that of tribals. The tribals were not given medical facilities, nor were cooperative arrangements made for the supply of improved seed. The procedure for releasing money to tribals was so cumbersome that by the time they got the money, the reclaimed land was overgrown. The plight of tribals in Assam is similar. In many cases tribals were forcibly evicted to settle the immigrants from East Pakistan. In the absence of any means of livelihood, the tribals have begun migrating to other states. Those who remain in their native places are exploited by the displaced persons. Ecological Problems India's national forest policy has not been successful in protecting the ecosystem. According to a UN estimate, 50 percent of the total land area in India is seriously affected by water and wind erosion. The displacement of fertile soil is estimated to be around 6 billion tons a year, thus depriving the country of a vast amount of total plant nutrients. About 4 million hectares of land are in ravines and eroding along mountain roads, causing frequent landslides. According to the UN estimate, the siltation rate of different rivers and water reservoirs varies from 150 to 500 acre feet per 100 square miles. Of the total catchment area of about 77.5 million hectares of 30 major river valley projects, nearly 11.6 million hectares require conservation treatment on a priority basis. At the same time, the area of sand cover in Rajasthan is reported to have increased by 18 percent since the early 1960s. Besides population increase, modern agricultural techniques also seem to have contributed to this process of desertification. It is because of such gigantic devastation that there is widespread demand for imposing a ban on tree felling There are reported to be about 500 central and state acts of legislation relating to environmental issues. Some fundamental changes have been proposed in the national forest policy. Thus the focus seems to be on the conservation of nature, which in turn implies increasing restrictions on the local people. The past experience shows that the forest policy seeks to protect forest wealth from forest dwellers, not from the unscrupulous contractors. In estimating the loss caused by the disturbance of the ecosystem, the dangers posed to the lives and economy of forest dwellers by floods and landslides are ignored. The afforestation program gives top priority to quick-growing species that can be used as raw material for forest-based industries. Even ecological considerations are often overlooked. On the other hand, the movements by the forest dwellers - Chipko, Bhoomi Sena, Silent Valley Movement, Jharkhand Movement - are insisting on a planned strategy incorporating the needs of the local ecology, local economy and the national interests. Only a people-oriented forest policy and development strategy will be able to bring the forest dwellers in the mainstream of national life without adversely affecting the ecosystem.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- PGDBA 2019 Notes: All Rights ReservedDocumento29 paginePGDBA 2019 Notes: All Rights ReservedAsif EkramNessuna valutazione finora

- Delhi Sultanate: The Five Dynasties that RuledDocumento7 pagineDelhi Sultanate: The Five Dynasties that RuledAsif EkramNessuna valutazione finora

- Mughal EmpireDocumento12 pagineMughal EmpireAsif EkramNessuna valutazione finora

- Tcs Testimony Contest 2017 - Syllabus: S.No TopicsDocumento4 pagineTcs Testimony Contest 2017 - Syllabus: S.No TopicsAsif EkramNessuna valutazione finora

- Afcat 1Documento10 pagineAfcat 1ismav123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Current Affairs Study PDF - September 2017 by AffairsCloud PDFDocumento169 pagineCurrent Affairs Study PDF - September 2017 by AffairsCloud PDFSaurav ShabbyNessuna valutazione finora

- Mughal EmpireDocumento12 pagineMughal EmpireAsif EkramNessuna valutazione finora

- TideDocumento11 pagineTideAsif EkramNessuna valutazione finora

- Session 2 - Cyberspace, Internet and TechnologyDocumento16 pagineSession 2 - Cyberspace, Internet and TechnologyAsif EkramNessuna valutazione finora

- Technical ReportDocumento17 pagineTechnical ReportAsif Ekram100% (2)

- Accounting For ManagersDocumento286 pagineAccounting For ManagersSatyam Rastogi100% (1)

- Creating Awareness on HealthcareDocumento10 pagineCreating Awareness on HealthcareAsif EkramNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- SOCIETYDocumento1 paginaSOCIETYRealee AgustinNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of GA3 Concentration on Rice Seed GerminationDocumento16 pagineEffect of GA3 Concentration on Rice Seed Germinationsalma sabilaNessuna valutazione finora

- AshinieDocumento48 pagineAshinieAshinie Astin100% (1)

- Chapter-7: Indigenous Knowledge SystemsDocumento27 pagineChapter-7: Indigenous Knowledge SystemsNatty Nigussie100% (3)

- Cotton Supply ChainDocumento18 pagineCotton Supply ChainShafiqNessuna valutazione finora

- The Philippine Strategy For Sustainable DevelopmentDocumento27 pagineThe Philippine Strategy For Sustainable Developmentkjhenyo218502Nessuna valutazione finora

- de Kiêm Tra Hki Tieng Anh 12.dap ÁnDocumento4 paginede Kiêm Tra Hki Tieng Anh 12.dap ÁnThảo PhươngNessuna valutazione finora

- Scope and Importance of Rural DevelopmentDocumento1 paginaScope and Importance of Rural Developmentkeyur solanki100% (2)

- The Color Encyclopedia of Ornamental Grasses - SedDocumento689 pagineThe Color Encyclopedia of Ornamental Grasses - SedKoriander von Rothenburg100% (2)

- The 6th Australasian Soilborne Diseases Symposium-Queensland, Australia 9 - 11 August 2010, Twin Waters AbstractsDocumento131 pagineThe 6th Australasian Soilborne Diseases Symposium-Queensland, Australia 9 - 11 August 2010, Twin Waters Abstractsamir-scribdNessuna valutazione finora

- Areas of concern for farm safety measuresDocumento4 pagineAreas of concern for farm safety measuresEric SapioNessuna valutazione finora

- Yusuf M.sc. Thesis Small VersionDocumento190 pagineYusuf M.sc. Thesis Small VersionTeka TesfayeNessuna valutazione finora

- Geography X Worksheets Lesson 4Documento7 pagineGeography X Worksheets Lesson 4Always GamingNessuna valutazione finora

- MangkonoDocumento3 pagineMangkonoAireeseNessuna valutazione finora

- Urban and Rural Land Use Planning Part 2 (CRESAR)Documento11 pagineUrban and Rural Land Use Planning Part 2 (CRESAR)Allan Noel DelovinoNessuna valutazione finora

- A Cost and Benefit, Case Study Analysis of Biofuels SystemsDocumento20 pagineA Cost and Benefit, Case Study Analysis of Biofuels SystemsRaju GummaNessuna valutazione finora

- Timetable Schedule 2022 23Documento89 pagineTimetable Schedule 2022 23Shaun PattersonNessuna valutazione finora

- Prospek Pengembangan Agribisnis Padi Organik Di KaDocumento9 pagineProspek Pengembangan Agribisnis Padi Organik Di KaEka DhanyNessuna valutazione finora

- Form 2 Holiday AssignmentDocumento152 pagineForm 2 Holiday AssignmentJavya JaneNessuna valutazione finora

- BUDGET NATURAL FARMING DOCUMENT SUMMARYDocumento13 pagineBUDGET NATURAL FARMING DOCUMENT SUMMARYGopi ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Effectiveness of Red and Blue Led Lights As The Primary SOURCE OF LIGHT IN THE GROWTH OF Solanum LycopersicumDocumento32 pagineThe Effectiveness of Red and Blue Led Lights As The Primary SOURCE OF LIGHT IN THE GROWTH OF Solanum LycopersicumBeverly DatuNessuna valutazione finora

- Current Affairs MrunalDocumento1.005 pagineCurrent Affairs MrunalAviroop SinhaNessuna valutazione finora

- 002Terminal-Report For Peanut ProductionDocumento29 pagine002Terminal-Report For Peanut ProductionROCHELLE REQUINTELNessuna valutazione finora

- ENG Farmura A4Documento2 pagineENG Farmura A4jeremykramerNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment of The CROPWAT 80 Software ReliabilityDocumento6 pagineAssessment of The CROPWAT 80 Software ReliabilitydarthslayerNessuna valutazione finora

- Profitability of Leek (Allium Porrum L.) in Three Production SystemsDocumento7 pagineProfitability of Leek (Allium Porrum L.) in Three Production SystemsMohammad KaziNessuna valutazione finora

- Hydroponic Lettuce Production Using Treated Post-Hydrothermal Liquefaction Wastewater (PHW)Documento16 pagineHydroponic Lettuce Production Using Treated Post-Hydrothermal Liquefaction Wastewater (PHW)Thabo ChuchuNessuna valutazione finora

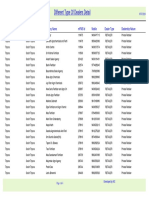

- Different Type of Dealers Detail: Mfms Id Agency Name District Mobile Dealer Type State Dealership NatureDocumento4 pagineDifferent Type of Dealers Detail: Mfms Id Agency Name District Mobile Dealer Type State Dealership NatureAvijitSinharoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Non Gmo Project Trifold ColorDocumento2 pagineNon Gmo Project Trifold ColorNotaul NerradNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 Energy and Exergy Analyses of Solar Drying System of Red SeaweedDocumento9 pagine2014 Energy and Exergy Analyses of Solar Drying System of Red SeaweedasifzardaniNessuna valutazione finora