Documenti di Didattica

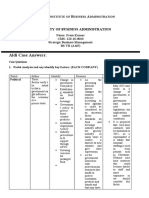

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Sectoral Interlinkage in India

Caricato da

Soumik BanerjeeCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Sectoral Interlinkage in India

Caricato da

Soumik BanerjeeCopyright:

Formati disponibili

NC Ray Memorial Paper Presentation, 2012

THE SALIENCE OF SERVICE-LED SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE IN THE INDIAN ECONOMY: WELFARE AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

A Paper by

ARPITA GHOSH SRIMANTI RAY DEBASMITA DAS SOUMIK BANERJEE

Department of Economics, St.Xaviers College, Kolkata, India

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT:

We would like to take this opportunity for thanking all our respected faculty members of Economics Department, St. Xaviers College (Autonomous), Kolkata. This project would not have been possible without our basic understanding of what Economics is all about, and towards this end the indelible effort of Professor Partha Pratim Ghosh, Professor Mallinath Mukherjee , Professor Dr. Ranjanendra Narayan Nag, Professor Bipra Kumar Das, Professor Pia Ghoshal, Professor Relina Basu and Professor Neelanjan Sen needs special mention. We would like to thank all those people who are associated with the National Economics Festival of St.Stephens College, Delhi University, that gave us an opportunity, and all our friends who motivated us, to present this paper, irrespective of any discrimination on any grounds. We are grateful to Rev. Dr. John Felix Raj S.J. (Principal, St. Xaviers College), Rev. Fr. Jimmy Keepuram S.J. (Vice-Principal, St. Xaviers College, Arts and Science Department) who have readily helped us in our endeavour. We have also benefited from the treasure trove of books on Economics at the British Council library and the Central Library of St. Xaviers College (Autonomous). Lastly, we cannot forget to mention the excellent infrastructural support we received from the College in the form the Central Library and the Cyber Room and are grateful to Computer Laboratory In-charge Mr. Sujit Chanda. However, the usual disclaimer applies.

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Abstract:

This paper attempts to look at inter-sectoral linkages in context of the Indian economy, using the more recent data on Indian GDP. It clearly shows that the most striking feature of Indias high economic growth in the past two decades was the boom in the service sector, and even the Reserve Bank of India acknowledges it as the mainstay of Indias phenomenal GDP growth. An increase in the final demand of services creates a pull-up effect that results in the growth of the other sectors as well. Furthermore, if tariff liberalization is coupled with an expansion of markets for the output of the export-oriented sectors then it can create the aforesaid pull-up effect. We undertake literature survey and empirical evidences, and try to formulate the results through an input-output analysis, and a general equilibrium model. Thence a look into the resultant unemployment and inequality consequences through the Harris-Todaro model shows that there is an explicit migration from the agricultural to the nonagricultural sector in hope for a better standard of living. Finally, certain policies have been prescribed against the aforesaid bane and for the boon of an even better sectoral interlinkage. Keywords: sectoral interlinkage, services, input-output analysis, general equilibrium

model, unemployment, inequality.

JEL Classification: O21, L80, C67, C68, J64

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

SUBJECT

Page Numbers

Introduction The Journey Begins

06

Literature Survey The Path Traversed

07 16

Input Output Analysis

17 20

A Simple General Equilibrium Model

21 25

Harris Todaro Revisited

26 29

Policy Prescriptions Towards A New Dawn

30 33

Conclusion The Way Ahead Appendix

34 35 37

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

LIST OF TABLES

PAGE NO

Table 1: Sectoral share of GDP at FC (at 1999-2000 prices) Table 2: Sector Wise Trend Growth Rate of GDP (at 19992000 Prices) Table 3: Sectoral Demand Matrices [(I - A)-1] (Demand Linkages)

10

11

14

LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Sectoral share of GDP at FC (at 1999-2000 prices) Figure 2: Sector Wise Trend Growth Rate of GDP (at 19992000 Prices) Figure- 3: Indian IT Sector Export Trend (1991-92 2007-08)

PAGE NO: 10

12

19

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

The Journey Begins:

Distinct structural changes give rise to the process of economic development in a country. With the economic progress, a countrys GDP basket enlarges and a shift in economic activity occurs from agriculture towards manufacturing and service sectors, i.e., non-agricultural sector (owing to higher income elasticity of demand of the latter than that of the former). This, in turn, leads to structural shifts. This process brings with it marked changes in the production process, consumption pattern and various other social indicators. Investigations of structural relationships help one understand not only the evolution and progress of such relationships but also the inter-sectoral adjustments over time. Hence, a clear perspective on the inter-sectoral dynamics could be useful in devising a conducive and appropriate development strategy. Sharp divergences in growth rates of different sectors are found to have serious implications for income distribution, inflation and current account deficit of an economy. A proper comprehension of the characteristics and trend of sectoral linkages also assumes importance in designing socially-just policies and effective monetary/credit policies. Thus, for a developing country like India where socio-economic problems such as poverty, unemployment and inequality influence policy decisions, it becomes important to study inter-linkages among the constituent sectors so that positive growth impulses emerging among the sectors could be identified and fostered to sustain the growth momentum. A good understanding of the inter-sectoral linkage dynamics is very important for framing effective monetary and fiscal policies to lead to development through inclusive growth. The annual real GDP growth of India from 2000-01 to 200203 is 4.7%; its pace accelerated after 2003-04 and the growth rate between 2003-04 and 2005-06 reached 8.3%. A large part of the credit behind the current phase of phenomenal Indian growth has been attributed to the structural reforms that got initiated in early 1990's. The changes associated with such reforms are likely to get captured in the more recent data than those lying further off. It was in this respect that we thought of exploring the sectoral inter-linkages in Indian economy using the more recent data on Indian GDP. In this paper we make an attempt to analyze the recent growth trends of India. We undertake literature survey and empirical evidences, and try to formulate the results through an input-output analysis, and a general equilibrium model. Thence we look at the resultant unemployment and inequality consequences.

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

The Path Traversed:

After achieving political, as well as economic independence, in 1948, Jawaharlal Nehru, To solve the problems of underdevelopment, unemployment and poverty, had taken the Soviet-type development strategy where the Indian government played a key role for industrialization and it was reflected in the Industrial Policy Resolutions of 1948 and 1956 and also in the Industrial (Development and Regulation) Act of 1951 which obliged firms to obtain a governmental license for entry and expansion with regard to the manufacturing sector. The two-sector growth model (1953) by P.C.Mahalanobis (the founder of the ISI where the I-O tables of India were compiled from the late 1950s to the early 1970s), gave the theoretical basis for these policies. Therefore, it is highly likely that the compilation of IO tables in the early years is closely associated with the economic planning policy adopted by the government. But broadly, in the context of the Indian Economy, the dynamics of interlinkages among the sectors has been examined by the researchers and policy makers in the following three ways: The Input-Output tables which not only reveal the broad trends in structural shifts but also provide valuable insights into the interdependence among the sectors, Purely statistical analysis of causality among the sectors, Econometric modeling exercises among various sectors of the economy. For example, Dhawan and Saxena (1992) and Hansda (2001) used the I-0 approach. Both causality tests and econometric models have been used by Rangarajan, 1982; Ahluwalia and Rangarajan, 1989; Bhattacharya and Mitra, 1989, 1990 and 1997; Sastry et al, 2003; Bathla, 2003, etc. Satyasai and Baidyanathan (1997) found that in the pre and early postindependence period, the industry sector had a close relationship with agriculture due to the agro-based industrial structure. The output elasticity of industry with respect to agriculture was 0.13 during 1950-51 to 1965-66 (Satyasai and Viswanathan, 1999). Rangarajan (1982) has found that addition of one percent growth in the agricultural sector stimulates the industrial sector output to the extent of 0.5 per cent, and thus, GDP by 0.7 percent during 1961-1972 .An important finding of the study is that the consumption linkages are much more powerful than production linkages. However, due to the stunned agricultural growth and favourable agricultural Terms-of-Trade, among other factors the industrial sector witnessed a slow

7

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

growth, followed by stagnation since the mid-1960s (Patnaik, 1972; Nayyar, 1978 and Bhatla, 2003). In fact the interdependence between the two sectors has found to be weakened during the 1980s and 1990s (Bhattacharya and Mitra, 1989; Satyasai and Viswanathan, 1997). For instance, Bhattacharya and Rao (1986) have found that the partial output elasticity of industry with respect to agriculture has declined from 0.15 during 1951/52 1965/66 to 0.03 during 1966/67-1983/84. The deteriorating linkages between agriculture and industry have been primarily credited to the deficiency in demand for agricultural products, decline in share of agro-based industries coupled with slow employment growth (Rangarajan, 1982; Bhattacharya and Rao, 1986). However, Ahluwalia (1985) denied the wage good constraint argument for the industrial stagnation of the mid sixties and contested presence of any relationship between agriculture and industry. Instead he argued for the supply constraints owing to poor infrastructure and poor productivity performance as the major reasons for stagnant industrial growth. In order to assess the contribution of services sector to the industrial growth, Banga and Goldar (2004)estimated a capital, labour, energy, material and services (KLEMS) production function for Indian manufacturing sector for the period 1980-81 to 1999-2000. Empirically, it found that the contribution of services to output growth increased substantially to 2.07 per cent per annum during the 1990s from 0.06 per cent per annum during the 1980s. The relative contribution of services to output growth was about one per cent in the 1980s and increased significantly to about 25 per cent in the 1990s. The paper by Sastry et al (2003) asserts that, for the period 1981-82 to 19992000, the forward production linkage between agriculture and industry has declined, whereas backward production linkage has increased. They also found significant impact of agricultural output on industrial output, and that agricultures demand linkage to industry has declined, while that of, from industry to agriculture has increased. Bathla (2003) carried out a comprehensive analysis of the inter-sectoral linkages in the Indian economy for the period 1950-51 to 2000-01. Under the grangercausality framework, no evidence of relationship was found between primary and secondary sectors, while primary sector was found to have a unidirectional causation with trade, hotels, restaurants, communication services and financing, insurance, real estate & business services sectors, the secondary sector was found to have bi-directional causality with them. Under the cointegration framework, strong evidence of existence of long-run equilibrium relationship was found among the primary, secondary and the specialized services sectors.

8

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

That most of the studies in India (and in many developing countries) have followed the traditional two-sector framework in a closed economy, it raises questions about the methodological reliability and the comprehensiveness of the findings. It is reasonable to argue that neither the two-sector model nor the close economy framework are appropriate to analyze the sectoral linkages in India, because India has been becoming more and more open since the reforms of 1990s, and since then (or even before), the growth of the economy has been led by the services sector. Services-led growth is the most prominent feature in the post-reform era (Rakshit, 2007), and, thus, any sectoral linkages analysis which circumvents the services sector does not provide comprehensive empirical findings. Thus, we observe that the process of economic development in Indian economy results in distinct structural changes since industrial stagnation in the mid 1960s. From a traditional agro-economy till the 1970s, the Indian economy has transformed into a predominantly services-oriented economy, especially since the mid 1980s. Economic reforms initiated in the mid-eighties, and their execution from early 90s, has not only brought about the structural transformation in the economy to a certain extent but also led to a substantial increase in the degree of integration with the rest of the world. With the continuous rise in the share of services sector in GDP for the Indian economy, there has been a phenomenal growth in distributive, communication, consumer and financial services, which, in turn, drives from increased demand from the commodity-producing sectors. This development has added a new dimension to the inter-sectoral linkages in the Indian economy. However, after witnessing remarkably high and stable growth during the 1990s, the Indian economy has recently shown the symptoms of recession. Thus, in designing appropriate long-run strategies to achieve a sustained 8 per cent growth-rate in real GDP (GDPR) envisaged in the Approach Paper for the Tenth Five-Year Plan [Planning Commission, 2001], a proper understanding of the sectoral linkages was given much importance. This issue has also become relevant for the conduct of monetary/credit policy as well. In the recent past, the Reserve Bank had reduced the bank rate and the cash reserve ratio (CRR) intermittently in order to stimulate the growth process. These measures, however, have not induced the desired result of increasing demand, both consumption and investment, possibly due to the persistence of certain sectoral rigidities in the Indian economy.

10

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Overall Growth Scenario of Indian Economy: The review of the changes in the sectoral composition of the GDP in Indian economy (for the period 1950- 51 to 2007-08) is presented in figure-1.it can be seen that over the three decades (from1970-71 to 2000-01), there is a major shift away from the agriculture towards services sector and industrial sector. The decade-wise analysis reveals that the share of real income primary sector (agriculture and allied activities) has declined from 55.11% in 1950-51 to 17.75% in 2007-08 while manufacturings share has accelerated from 10.16% in 1950-51 to 20% in 2007-08. Tertiary sector has witnessed a continuous expansion with a share in total national income rising from 34.27% in 1950-51 to 62.87% 2007-08. Table 1: Sectoral share of GDP at FC (at 1999-2000 prices) (in percentage) Year 1950-51 1960-61 1970-71 1980-81 1990-91 2000-01 2007-08 Agriculture Allied 55.11 50.62 44.26 37.92 31.37 23.89 17.75 Industry 10.62 13.13 15.45 17.45 19.8 19.99 19.38 Services 34.27 36.25 40.3 44.63 48.83 56.12 62.87

Source: Handbook of Statistics on Indian economy, 2007-08

During the 1990s, however, there was a sharp rise by about 8 percentage points in the share of services sector and almost a similar fall in the agricultural sector, with very little change in the share of the industrial sector.

Figure-1: Sectoral share of GDP at FC (at 1999-2000 prices)

10

11

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Table-2 provides average per annum growth rate in respect of different sectors of the economy. Table 2: Sector Wise Trend Growth Rate of GDP (at 1999-2000 Prices) Year GDP at FC Agriculture & allied 2.71 1.51 1.74 2.97 3.34 3.09 Industry Services

1950/511959/60 1960/611969/70 1970/711979/80 1980/811989/90 1990/911999/2000 2000/012007/08

3.68 3.29 3.45 5.17 6.05 7.76

5.99 5.15 5.07 6.41 6.63 7.46

4.40 4.74 4.45 6.35 7.32 9.55

Note: Trend Growth rate is estimated using equation ln(Y) = a + b (Time) at 1999-2000 prices. Source: Handbook of Statistics on Indian economy, 2007-08

The decade-wise annual trend growth rates in each sector reflects that the performance of all the sectors was reasonably good during the 1980s indicates a shift towards higher growth only from the early eighties (Figure 2). In the 1960s and 1970s primary sector growth rate was below 2.0% compared to a higher growth rate of 2.74% during the 1950s. A similar picture of high output growth is witnessed in industrial sector in the 1950s (6%) but a comparatively lesser rate (5.15% and 5.07%) is found in the subsequent decades. Thus low growth rate in the industrial sector in the 1970s was also accompanied with low growth in agricultural sector, pointing to a close linkage between the sectors. Industrial growth rate has been relatively high during 1980s when agricultural growth was also relatively high. In contrast, the tertiary sector has witnessed phenomenal growth from 4.40% in the 1950s to 6.35% in the 1980s and 7.32% in the 1990s.

11

12

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Figure- 2: Sector Wise Trend Growth Rate of GDP (at 1999-2000 Prices)

Comparing the sectoral shares in GDP since the 1950s, we find that the agriculture and allied activities has followed downward trend overtime, with industry remaining nearly constant till 1970s and then showing an upward trend since 1980s, and services sector share rising in the GDP. Since the early 1950s, share of services sector in GDP exceeded that of the industrial sector, but the same remained smaller than that of the agricultural sector till the 1970s. At a glance, the declining contribution of agriculture to GDP gives an indication that the role of agriculture in the national economy has become less and less important. While the share of agriculture in national income has been declining, the workforce engaged in agriculture has exhibited only a marginal decline: whereas 75.9% of the total workforce was engaged in agriculture in 1961, the figure declined to 59.9% in 2000-01 and then to 52.0% in 2006-07. In absolute terms, agriculture provided employment to 237.8 million persons in 2000-01 (Economic Survey, 2007-08). Vogel (1994) and Bhatla (2003) argue that agriculture continues to be an important sector in terms of absorbing twothird of the total work force and positively influencing development of manufacturing and overall economy despite a deceleration in its share in total income. Bhatla (2003) also remarked that despite of differential growth across the sectors, agriculture is still seen to stimulate industrial and overall economic growth. Further, the existence of forward and backward production linkages

12

13

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

means that the importance of the agricultural sector cannot simply be implied just from the value of its direct output. A Review of Demand Linkages: The demand linkage between agriculture and industry operates through agricultural income. An increase in agricultural income brings about an increase in the demand for industrial consumer goods and some producer goods, such as pumps, tractors, fertilizers, pesticides, etc. According to Ahluwalia (1985), there are certain consumer goods such as clothing, footwear, sugar and edible oils, which accounts for about a fourth of the value added in the consumer goods sectors, for which rural consumption is over three times than the urban consumption. Rangarajan (1982) observed that the rural demand in India for industrial consumer goods account for as much as two-thirds of the total demand for them. The Terms-of-Trade (TOT) (the relative price ratio) between agriculture and industrial products plays very important role in enhancing the demand linkages between the two sectors. A favourable TOT for agriculture leads to higher income of the agricultural sector, and thus, creates more demand for industrial goods. On the other hand, the same favourable TOT will squeeze industrial growth by reducing the profit margins through increase in the product wage rate. The TOT for agriculture in India has found to be favourable since the mid 1960s, except the unfavourable TOT for the period 1977-78 to 1983-84. Chakravarty (1974) examined the implications of agricultural TOT on Indian industries, based on the linkages through food grain supply. He postulated that beginning from 1964-65, a favourable agricultural TOT was instrumental in squeezing the profit margins of the industrial sector through an increase in the product wage rate. Rao and Maiti (1996) also observed that the impact of a rise in relative food grain price on the demand for industrial consumer goods was significantly negative during 1952-90(cited in Deb, 2002). The demand linkage can be examined by using the Leontief inverse matrices, i.e. the (I A)-1 matrix, where A is the input-output coefficient matrix. Such inverse matrices are given in Table 3.

13

14

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Table 3: Sectoral Demand Matrices [(I - A)-1] (Demand Linkages) Year 1979-80 Agriculture Industry Services 1989-90 Agriculture Industry Services 1993-94 Agriculture Industry Services 1998-99 Agriculture Industry Services 2003-04 Agriculture Industry Services Agriculture 1.214 0.135 0.049 1.220 0.319 0.144 1.187 0.297 0.149 1.152 0.420 0.087 1.265 0.466 0.123 Industry 0.260 1.601 0.269 0.104 1.729 0.404 0.087 1.704 0.457 0.075 1.831 0.216 0.077 1.958 0.247 Services 0.083 0.191 1.139 0.074 0.378 1.318 0.066 0.330 1.334 0.051 0.457 1.207 0.061 0.501 1.213

Source: Data up to 1993-94 are from Sastry et al (2003) and for 1998-99 and 2003-04 are from Kaur(2009)

From the table, we find that a rise in the demand in agriculture by one unit was likely to raise demand for industrial goods by 0.260 units and demand for services by 0.083 units in 1979-80. In 1993-94, one unit of rise in the agricultural output was likely to enhance the demand for industrial goods by 0.297 units and that of for services by 0.149 units. Agricultures demand linkages to industry further increased to 0.446 units in 2003-04, while that to services declined to 0.123 units during the same. Unlike the agricultures demand linkages to industry, the industrys demand linkages to agriculture has been weakened during both the pre- and post-reform period, whereas industrys demand linkages to services became almost double in 1993-94 and then it returned to the initial position in 2003-04. The services-sectors demand linkages to the agriculture sector have remained more or less same over the pre and post-reform period, barring some marginal increase during 1979-80. However, recent trend shows an increasing linkage between the two. On the other hand, the service-sectors demand linkages to

14

15

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

industry increased by about 44% during 1968-69 to 1993-94 and by about 52% during 1993-94 to 2003-04. Services led Growth: The most striking feature of Indias high economic growth in the past two decades was the boom in the service sector. This service sector is included in the non-agricultural sector and hence draws our attention from the traditional agriculture-industry framework to the overall growth through service sector linkages. Service-led growth is sustainable because the globalisation of services is just the tip of the iceberg (Blinder 2006). Services are the largest sector in the world, accounting for more than 70% of global output. The service revolution has altered the characteristics of services. Services can now be produced and exported at low cost (Bhagwati 1984). The old idea of services being nontransportable, non-tradable, and non-scalable no longer holds for a range of modern impersonal services. Developing countries can sustain service-led growth as there is a huge room for catch up and convergence. A booming service sector could upset three long-held tenets of economic development. First, services have long been thought to be driven by domestic demand. They could not by themselves drive growth, but instead followed growth. Second, services in developing countries were considered to have lower productivity growth than industry. As economies became more service oriented, their growth would slow. Third, services jobs in developing countries were thought of as menial, and for the most part poorly paid, especially for lowskilled workers. As such, service jobs could not be an effective pathway out of poverty. The core of the argument is that as the services produced and traded across the world expand with globalization, the possibilities for all countries to develop based on their comparative advantage expand. That comparative advantage can just as easily be in services as in manufacturing or indeed agriculture. Unlike the two-way linkages between agriculture and industry, the linkages between agriculture and services sector is one-way and this linkage is mainly backward linkage, rather forward linkage. There are considerable evidence that investments in some special services such as transport and communication, storage, building of rural roadways, banking and financial facilities, trade and hotels, social services such as education, hospitals and other infrastructure, etc. increases agricultural productivity. The growth in specialized services can induce higher rates of economic growth, and is also likely to strengthen agriculture-industry linkages. Similarly, with the rise in per capita income demand for specialized services that act as inputs in agriculture will increase, because the demand for services is highly income

15

16

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

elastic. This, in turn, will induce industrial growth, and stimulates added agroproducts. The services sector has been the mainstay of the Indian growth process in the 1990s. While the share of services has been ruling high ever since independence, it has received a major fillip only in the 1990s. Indeed, contribution of the services sector to the overall GDP growth peaked an all time high of 65.1 per cent in the 1990s up from 43.6 per cent in the 1980s. As a result, the services share in GDP went up by a spectacular 7.9 per cent in a single decade of the 1990s touching the mark of 48.5 per cent in 2000-01 while the sector took about four decades to improve its share by 12.6 per cent to 40.6 per cent in 1990-91 from 28.0 per cent in 1950-51. The ascendancy of services has had a stabilizing effect on the growth process itself. To quote from the Reserve Banks Report on Currency and Finance, 2000-01, it is the services sector which has kept the GDP growth around 6.0 per cent in the 1990s when industry and agriculture sectors did not perform relatively well (p. iii 44). Thus, the services sector has been the most dynamic sector of the Indian economy, especially over the last ten years (National Statistical Commission, 2001, art 7.1.2) The application of input-output analysis has revealed that Indian economy is quite service intensive and industry is the most service-intensive sector. Banga and Goldar (2004) found that services input contributed for about 25 percent of output growth of registered manufacturing during 1990s (as against 1 percent during 1980s), and that increasing use of services in manufacturing has significant favorable impact in total factor productivity (TFP) growth of organized manufacturing sector. These observations, in turn, imply that excluding the service sector from the analysis understates the agricultureindustry linkages. Given these linkages and the recent services sector boom, the apparent question is how to interlink the services sector with agriculture and industry, and how it is going to impact the agriculture-industry linkages.

16

17

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Input-Output Analysis:

With such rapid growth, significant changes occur in the Indias economic structure and the need for the data and the analytical tools that capture such changes is also increasing among policy makers, researchers and business practitioners. The input-output (I-O) table that describes all the transactions between the industries of an economy is one of the useful statistics in order to meet such demands. Here we undertake an input output analyses to delve into the matters of inter sectoral interlinkage. The input output analysis is demand driven, whereby the change in final demand of a sector causes a change in the output of the concerned sector, as well as a change in the output of the interlinked sector. However, it is assumed that there is no capacity constraint. Let Mij denote the inputs into sector j from sector i, & Mj denote the output of sector j. We define aij = Mij/Mj, where aij denotes the amount of purchases from each sector to support one unit of output of sector j. In specifying the final demands for each sector, one obtains the following set of relations for each sector: Mi = =>Mi + Ci; i=1(1) n = Ci; i=1(1)n .(1)

Where Ci is the total final demand, Mi is the output of sector i, & aijMj is the sum of intermediate demand. Let us consider 3 sectors. Let, X denote the formal sector (which can be taken as the service sector), Y denote the import competing sector (which can be said to be the manufacturing sector), & Z denote the export-oriented agricultural sector. Thus, now i = {X, Y, Z}; j = {X,Y,Z}. Thus, equation (1) can be written as follows: MX - aXXMX aXYMY aXZMZ = CX MY - aYXMX aYYMY aYZMZ = CY MZ - aZXMX aZYMY aZZMZ = CZ In matrix form this can be written as

17

18

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

=> => Where I = => M =

-1

= M= C, ,A= C ,M= ,C=

If (I A), known as the Leontief matrix, is non-singular, & I is the identity matrix. The matrix (I A)-1 is known as the Leontief inverse matrix, which represents the direct & indirect requirements of gross output in each line of activity to support one unit of final demand in each line of activity. The sum of the elements of the ith row of the total requirement matrix (I A)-1 is normally taken to be the measure of forward linkage. It is denoted by bi0 = ,& it shows the increase in output of the ith sector used as inputs for producing an additional unit of the final sector output. Similarly, sum of the elements of the jth column of the total requirement matrix (I A)-1 is normally taken to be the measure of forward linkage. It is denoted by b0j = , & it shows the input requirements for a unit increase in output of the jth sector, given each sectors share in total final demand. Thus, an index of the backward linkage is derived in the following way:

The existence of the solution the above problem requires > 0, where =

Assuming that the above holds, the solution are as follows MX = BXXCX + BXYCY + BXZCZ .(2)

18

19

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

MY = BYXCX + BYYCY + BYZCZ MZ = BZXCX + BZYCY + BZZCZ

.(3) .(4)

Where, BXX = BYX = BZX =

, BXY = , BYY = , BZY =

, BXZ = , BYZ= , BZZ =

Bij > 0, for all i,j ={X,Y,Z}. Now let us suppose there has been a rise in the final demand of X. i.e., CX has risen. This might be due a number of factors. Let us assume that there has been a rise in the external demand of X (the figure below shows the rising value of exports of IT and ITES of India, in US billion $, over the years. This can be attributed to a rise in the external demand of the same. This forms the empirical base of this analysis). Figure- 3: Indian IT Sector Export Trend (1991-92 2007-08)

19

20

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Total differentiating (2), we get,

Clearly if CX rises, denoted by CX, there is a rise in the output of the X sector, since is positive, given the Hawkins Simons condition. Now, total differentiating (4), we get,

Thus, an increase in the final demand of the X-sector induces a rise in the output of the Z-sector, since is positive, given the Hawkins Simons condition. This clearly shows the positive interlinkage between the X and the Z sectors. Thus, an increase in the output of the formal sector (here X), induced by a rise in the final demand of its output, pulls-up the output of the agricultural sector (here Z).

20

21

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

A Simple General Equilibrium Model:

Now we construct a general equilibrium model to have a look into sectoral interlinkage, and its consequent effect on inequality and unemployment. We make the following formalization: We take a 3 sector small open economy. Let X is the output produced in formal service sector, where X is produced with skilled labour and capital. Skilled labour is specific to sector X. Moreover, X uses capital-intensive production techniques. Let Y be the output produced in import-competing manufacturing sector, where Y is produced with unskilled labour and capital, and, is tariff protected. We assume an ad-valorem tariff rate t. Moreover, Y uses labour-intensive production techniques. Let Z be the output produced in export-oriented agricultural sector, where Z is produced with unskilled labour and land. Land is specific to sector Z. Moreover, Z uses land-intensive production techniques. is fixed unionized skilled-labour wage-rate; is unskilled-labour wage-rate. Assuming unskilled labour-mobility, the wage-rate of unskilled-labour is same in sectors Y & Z. r is return to capital. R is return to land. L is the total fixed stock of labour, i.e., = , where denotes the total skilled labour available in the economy, & Lu denotes the total unskilled labour available in the economy. K is total stock of capital, & is total fixed stock of land. s are the commodity prices, where i=x, y, z. is the per unit requirement of ith factor of production for the unit output of the jth product, which is fixed. Therefore the price equations are: .. (5) . (6)

21

22

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

.. (7) . (8) (9) .. (10) (11) Now, differentiating (5) totally, . (5a) .. (5b) .. (5c) Similarly from (6) and (7), .. (6c) ... (7c) where,

and

is the income share of the ith factor in the jth sector.

Now representing (5c), (6c) and (7c) in matrix forms,

So for the solution to exist,

22

23

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

, which holds true since the factor income shares are always positive. We undertake the following Comparative statics:

1) Trade Liberalization : Let there be a trade liberalization that is, fall in the tariff rate t. This means that py (=py*(1+t)) falls. Given Rybczynskis theorem, from equation (4), we conclude that there will be a fall in the unskilled wage wu, given the factor intensity assumption. From the figure we see that there is a fall in the output of Y from Y0 to Y1. This would shift the labour demand curve downwards, resulting in a fall in wage wu in the Y-sector, and a resultant fall in employment. However, the unemployed labour would not move to the export oriented agriculture sector Z. this is so, because a further increase in the labour supply in sector Z would cause the wage rate to fall even in the sector Z.

23

24

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

However, the skilled wage is fixed. Thus, there is a clear rise in inequality between the factor incomes of the two types of labour. One interesting thing to note here is that sector Y being labour-intensive, the fall in output in the Ysector will lead to a greater displacement of labour than sector Z can absorb, it being land-intensive. 2) Rise in the external demand of the formal service sector : Let there be a rise in the external demand of X (as shown in our inputoutput analysis). This raises , thus by Stolper-Samuelson result rate of interest r also rises. Taking capital (K), being an increasing function of r, there is an increase in capital. X being a capital intensive sector, by Rybczynskis theorem, production of X must also rise, as evident from equation (5) .

The increase in the production of X pushes the labour demand curve (which is of skilled labour) outwards. However, wage being fixed at , an outward shift of the labour demand curve results in the fall in unemployment from an initial level U1 (L1L2) to a new level U0 (L3L2).

24

25

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

3) Rise in the external demand of the export-oriented agricultural sector: Let there be a rise in the external demand of the export-oriented agricultural sector Z. the demand curve for the output of sector Z shifts outwards. As a result, Pz* rises, and the output also rises. However since land is fixed in supply, it would result in greater demand of the other factor of production, unskilled labour. Thus, the labour demand curve will shift outwards, resulting in a rise in wage in the Z-sector.

However, labour being mobile between Y & Z sectors, this would bring in labour from the Y sector, shifting the labour supply curve outwards, thereby reducing wage to the previous level, but absorbing the displaced labour from the Y-sector.

25

26

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Harris-Todaro Revisited:

After having constructed a general equilibrium model to look at the different facets of sectoral-interlinkage, let us now look into the matter of unemployment in a different way, using the marginal productivity of labour analysis, a la Harris Todaro (1970). Suppose there are L workers in the economy with LX in the export-oriented service sector, LY in the import-competing sector, and LZ in the agricultural sector, where LX contain skilled labour LS, and LY & LZ contain unskilled labour LU. Wage in the formal sector is fixed at the unionized level of . In the agricultural sector, wage is wuz, and the import-competing sector wage wuy coincides with agricultural sector wage wuz as per assumption. We assume that the number of jobs in the formal sector, i.e., LX is fixed (unless there is any parametric change). We further assume that following reasons: is greater than wuz this can be attributed to the

(i) The service sector X employs skilled labour, & the agricultural sector Z employs unskilled labour. Naturally the former wage will be more than the latter. (ii) In the formal service sector the presence of labour-unions & pro-labour customs ensure that the wage in the service sector is higher than the agricultural sector, where the aforesaid conditions do not hold. (iii) The government usually sets a wage-flooring to protect the interests of the labourers. However, this is usually followed in the formal sector which is organized & supervised, & generally employs skilled workers. However, in the agricultural sector, these policies go for a toss. (iv) Workers in the service sector face the threat of being fired. Then they have to either be employed in the informal sector, or go back the agricultural sector to work. Thus, this entails a higher wage in the formal sector. (v) In the agricultural sector, there are incentives for workers to expend effort when labour cannot be directly supervised without incurring tremendous costs.

26

27

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

(vi)

If there is an increase in world demand for goods produced in the service sector (as mentioned earlier) then the price of the good will rise, & the benefits will pull-up the wage rate in the service sector.

As is exogenously fixed, there is a fixed amount of labour employed in the service sector (unless some parametric changes occur). Thus, if there are more workers than LX in the non-agricultural sector then some would have to find job in the import-competing sector, and the rest remain unemployed. The crucial assumption of this model is that workers base their migration decisions on their expected incomes. The wage-differential created between the agricultural & the non-agricultural sector leads to individual migrating from the agricultural sector to the non-agricultural sector. Moreover, we assume that people migrate in hope of getting a job in the formal service sector which gives a much higher wage. But this migration incurs a cost, which is denoted by C, C > 0. The problem of obtaining jobs in the service sector depends on the ratio of vacancies to job seekers. We denote this by p. Moreover, there is the importcompeting sector, in which a migrant can get absorbed in the event that he gets no job in the service sector. Thus, the expected wage in the non-agricultural sector is p. + (1 - p). wuy (12)

Over-crowding in the non-agricultural sector due to high rates of migration from the agricultural areas results in unemployment in the formal service sector a part of which gets absorbed in the import-competing sector. If employment in the service sector is increased by 1 unit, then rural employment falls by / wuz units. Thus, =-( / wuz) < 0 people to migrate from the agricultural to the non-

z This induces / wu agricultural sector.

Now, let us denote the probability of an unemployed migrant to be absorbed by the import-competing sector by q, albeit at a lower wage wuy (= wuz ). or he remains openly unemployed with a probability (1 q). thus, the expected value of this set of possibilities is q. wuy + (1 q).0 = q. wuy (being openly unemployed means that he gets zero wage).

27

28

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Now, the probability of getting a job in the service sector is given by LX / (LX + LY). the number LX denotes the number of jobs there are in the service sector, while, the number (LX + LY) gives us the total number of potential job-seekers. The ratio of the two, thus, gives, the chances that a migrant will get a job in the formal service sector or the import-competing sector. Thus, the expected income from the service sector is .[LX / (LX + LY)]

Similarly, the expected income from the import-competing sector is wuy.[LY / (LX + LY)] Thus, migration continues as long as .[LX / (LX + LY)] + wuy.[LY / (LX + LY)] C + wuz, (13) Since the weighted expected income from non-agricultural sector happens to be greater than the wage in the agricultural sector, plus migration cost. We denote the right-hand side of the above expression as . When equality holds, migration equilibrium occurs, i.e., ex-ante people are indifferent between migrating and not migrating.

28

29

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

The figure in the previous page shows the results of our model. MPLZ is the marginal productivity of labour in the agricultural sector, & MPL* is the marginal productivity of labour in the non-agricultural sector. OO denotes the total labour endowment in the economy, i.e., . LZ is the employment in the agricultural sector. LX is the employment in the formal service sector. LY is the employment in the import-competing sector. The remaining U ( - LZ - LX - LY) is the level of unemployment in the economy. The aforesaid results are clear from the figure. However, some points are to be noted here: (i) Ex post, the situation may be different those who landed a job in the formal sector would be satisfied; but those who had to be contend with an informal sector job would regret that they made the move. (ii) The equilibrium concept implies a particular allocation of labour between the three sectors of the economy. This is because it is the allocation of labour that affects the perceived probabilities of getting a job. (iii) The equilibrium concept can be extended to more than two sub-sectors in the non-agricultural sector or in several sectors in agriculture.

29

30

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Policy prescriptions - Towards A New Dawn:

Migration from the agricultural to the non-agricultural sector, usually taken to be rural-urban migration, reduces population pressure in the rural areas and, thereby, should improve economic conditions and reduce rural poverty. However, disparities between urban and rural areas in terms of income and employment and the availability of basic infrastructure and services persist. A major effort is required to ensure that the urban areas can absorb the growing urban population and that urbanization will not result in an urbanization of poverty. During the 1950s and 1960s, most governments recognized the need for simultaneous development of agriculture and industry, of rural and urban areas, but this was impossible in view of the scarcity of the available resources. An exclusive focus on rural areas would result in an under-investment in urban areas and this would limit the growth of the urban sector and its ability to absorb the rural labour surplus. An exclusive focus on urban development would produce similar results, because it would accelerate rural-urban migration and reduce food production per-capita. Industrialization would pertain to import machinery and other capital-intensive industrial inputs from developed countries and the cost of importing capital goods would nullify the gains made by import-substitution. The import-substituting industries need protection against foreign imports of similar goods through import tariffs, but this makes the industries less efficient and competitive. Under a sustainable development programme the following targets are listed; Empowerment of communities and development of livable cities, Alleviation of rural and urban poverty through participation, Establishment of linkages between agricultural and non-agricultural development, Management of integrated area-function-participation development. Impact of government policies: Since it has been seen that urban development through creating urban formal sector jobs leads to migration more and consequent urban unemployment it would be more efficient to portray on rural development programmes for the

30

31

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

government. The impact of government agricultural policies is a serious matter of concern that has not been given due attention in our country. The Terms-ofTrade may be affected, either through demand or supply side, due to significant effect of price policies undertaken by the government .According to Bhadhuri ,By ignoring the factors like ., and perhaps the most importantly, the agricultural minimum support price system of the government we cannot even hope to present a comprehensive and realistic empirical analysis of the evolving pattern of agriculture- industry interactions. Examining the impact of government interventions in agriculture (e.g. input subsidy, minimum support price, etc.) on agricultural growth are required as most dual economies are starkly differentiated between the traditional agricultural sector and the modern sector having little connections. Nevertheless the impact of globalization and liberalization and the subsequent movement towards free trade has opened up a new dimension for the agricultural sector. We need to examine the policies of World Trade Agreement of Agriculture and the impact of external forces on sectoral interlinkage. As Vyas (2004) observed such move will undoubtedly affect the product mix and the input composition in agriculture sector in a significant way, and thereby, the sectoral linkages. The results that have cropped up in this paper give rise to the following policy prescriptions: Inter-sectoral resource transfer: An important aspect of linkage between the two sectors is the transfer of surplus resources such as labour and raw from agricultural to non-agricultural sector. However, the estimation of inter-sectoral resource flows between agriculture and non-agricultural sector in a country like India is impossible as the agricultural activities are informal in nature and more than 80 percent farmers are small and marginal farmers (who are not able to produce any marketable surplus). Technological change should also be welcomes by the agricultural sector in order to usher in higher productivity, profitability and more marketable surplus. The government should take necessary policies in order to boost up sectoral linkage through resource transfer.

31

32

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Subsidy in the non-agricultural sector (with migration restrictions): One way to deal with the unemployment problem is to provide wage subsidy in the formal service sector. As such the firms in that sector have to bear a lesser wage cost, and thus, would employ more labour, thereby, reducing unemployment in that sector, as shown in the adjacent diagram.

But this actually worsens the situation by enlarging the unorganized sector since more and more people migrate from agricultural sector with expectations of a higher wage (since the propensity to migrate from the agricultural to the non-agricultural z sector is > wuz). / wu > 1, as This shifts the labour supply curve in that sector outwards and unemployment rises. Hence a mixed policy that combines urban wage subsidies with migration restrictions would serve the purpose. Interestingly an alternative policy for shrinking the informal sector excluding the migration restriction would be subsidization of employment in agriculture. Thus the policy recommendation regarding employment also suggests a fine link between agricultural and urban sector.

32

33

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

An eye for the international market: The government should encourage the production of goods and services those produce in line of the international market. As such there would be an increase in world demand for these commodities which would yield positive results as shown in our analysis in the paper. Development of human capital: The service sector employs skilled labour. Thus to accommodate the unskilled labour of the remaining two sectors in the booming service sector the government must take measures to develop human capital such as health and education. Education would help the people of the country to acquire skills which would make them eligible for a job in the booming sector. Efforts must be taken by the government to minimize the time-lag of skill acquisition. Vocational training can be of help. Moreover, a sector that is booming would require workers who can work without falling sick. Thus health is an important aspect. Efforts must also be taken for developing the rural sector which would automatically prevent people from migrating to the non-agricultural sector, thereby, creating multiplier effects along with the wage-subsidy policy there must also be a labour market regime that protects the interests of the labourers, but at the same time it shouldnt be too strict so as to put the entrepreneurs at a loss. The structural reforms after the BOP crisis, so far, have been perceived to be more successful in increasing the efficiency and competitiveness of Indian industry. Exogenous shocks to economy through agriculture as a fall-out of adverse weather conditions remains a reality even today. In such an event, the presence of bi-directional sectoral linkages between industry and services (in the absence of directional causality running from agriculture to non-agriculture growth) can still help sustaining the growth momentum through appropriate policy initiatives favoring these sectors. Policy initiatives favouring industry and services in such a set up would be effective in neutralizing some of the negatives of adverse shocks from agriculture. In the same spirit adverse shocks either to industrial and/or services growths are likely to get magnified and policy initiatives directed towards agriculture alone to counter this need not be effective in yielding the desired result.

33

34

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

The Way Ahead:

The present paper focuses on the service-led growth of the Indian economy, supporting the recent trend. The paper leads to the following points: (i) An upward surging trend in final demand of services (which can be attributed to a rise in external demand) increases the output of the said sector, and creates a pull-up effect that results in the growth of the other sectors as well. This pull-up effect helps in reduction of unemployment, and a better standard of living for the labour employed in the different sectors. An increase in the final demand of the export-oriented agricultural sector also creates the aforesaid pull-up effects and a favourable standard of living for the employed labour. Tariff -liberalization leads to a fall in output of the import-competing sector, resulting in a fall in the standard of living of the factors employed in that sector (in our paper its the unskilled workers). However, if tariff liberalization is coupled with an expansion of markets for the output of the export-oriented sectors, then it might lead to an increase in output of the import-competing sector due to greater pull-up effect. But this also depends on the ability of the firms in the said sector to shed its infancy. There is an explicit migration from the agricultural to the nonagricultural sector in hope for a better standard of living. To tackle this problem more job creation, along with restrictions on migration & rural development is needed.

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

It has been found that deficiency of demand in one sector is the main constraint on other sectors growth. Suppose, a particular allocation of investment between agriculture and non-agricultural sector results in such increases in outputs of the two sectors that there is an excess supply of (demand for) non-agricultural (agricultural) output. If the deficiency in demand for non-agricultural output cannot be eliminated by increasing agricultures share in total investment because constraints restrict the expansion of agricultural output, then the growth potential of agricultural sector is the limiting factor for growth. Agricultural stagnation, by limiting food and intermediate good supplies, markets, sources of savings and labour, could constrain industry, while non-agricultural stagnation by limiting supplies of capital and intermediate goods and markets could restrict agricultural development. While substitutes through foreign trade may be available, difficulties of export expansion and consequent foreign exchange shortages may not allow such routes to be taken. However, for greater social upliftment, there should be an increased emphasis on human capital and a greater participation of the people in the growth process. The recent initiative of

34

35

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

inclusive growth is a step in the right direction. Further studies can be taken in the following fields: Firstly, it has been implicitly assumed in our paper that exchange rate remains fixed. If the Central Bank intervenes in the foreign exchange market & there is a devaluation or evaluation of the domestic currency, it would entail some interesting results. The results would change in case of a flexible-exchange rate system, as is followed nowadays by most countries. This issue needs a further investigation in a macro-economic framework. Secondly, as a country slowly transforms from following an Import-Substitution policy to an Export-Promoting one, the role of the import-competing sector changes, provided it grows up. Then the whole framework would show different results. However, this particular field can be captured in a framework with at least four sectors. Thirdly, the informal sector plays a vital role in the Indian economy. The informal sector contributes to employment in India significantly during the period 1977-78 from 92.2 per cent to 93.6 per cent in 2004-05. On the other hand the share of contribution of GDP in informal sector was 68.1 per cent during the period from 1977-78 and about 57.6 per cent in 2004-05. Contrary to the western development model of Lewis which suggests that the surplus labour from the subsistence sector would be absorbed in the industrial sector as development takes place, no such shift of labour from agriculture to modern industrial sector has taken place in India. Rather the shift has been from agricultural sector to the informal service sector which is quite sizeable in contributing to the economys output. Moreover, there also exists dualism and contract-farming in the agricultural sector. This suggests that existence of informal sector is likely to have a huge effect on the income distribution and employment of an economy and it needs further research in future. Fourthly, Environmental Sustainability is an essential global pursuit, because environmental degradation is inextricably and logically linked to the problems of poverty, hunger, gender inequality, and health. Livelihood strategies and food security of the poor often depend directly on functioning ecosystems and the diversity of goods and ecological services they provide. Insecure rights of the poor to environmental resources, as well as inadequate access to environmental information, markets, and decision-making, limit their capacity to protect the environment and improve their livelihoods and well-being. Thus, protecting and managing the natural resource base of economic and social development and changing consumption and production patterns are fundamental requirements.

35

36

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

References:

Bhattacharya Kaushik, Sastry D V S, Singh Balwant and Unnikrishnnan N K: - Sectoral Linkages and Growth Prospects: Reflections on the Indian Economy , pp. 2391-2393. Bhattacharya Rudrani: - Agro-industry, Inequality and Sectoral growth , pp. 3-9. Bleek Schmidt Friedrich, Malley Jurgen, Spangenberg H.Joachim: "Towards a Set of Proactive Interlinkage Indicators as a Compass on the Road towards Sustainability. Jones R.W.: - The Structure of Simple General Equilibrium Models. Lanjouw O Jean, Lanjouw Peter: - The Rural non-farm sector: issues and evidence from developing countries , pp. 12-20. Marjit Sugata: -Agro-based Industry and Rural Urban Migration. Marjit Sugata: -International Trade and Economic Development, Oxford collected essays, Trade & Wage Gap in Developing Countries, pp. 86-105. Marjit Sugata: -International Trade and Economic Development, Oxford collected essays, Trade & Wage Inequality in Developing Countries, pp. 106-121. Saikia, Dilip: - Agriculture-Industry Interlinkages: Some Theoretical and Methodological Issues in the Indian Context, pp. 15-23. Saikia, Dilip: - Trends in Agriculture-Industry Interlinkages in India: Pre and Post-Reform Scenario", pp. 12-16. www.indiastat.com www.mospi.nic.in www.rbi.org.in

36

37

SECTORAL INTERLINKAGE, INCOME DISTRIBUTION AND UNEMPLOYMENT

APPENDIX:

Relevant data to figure 3 (page-18):

INDIAN IT SECTOR EXPORT TREND YEAR VALUE( US BILLION $) 1991-92 0.194 1992-93 1993-94 1994-95 1995-96 1996-97 1997-98 1998-99 1999-00 2000-01 2001-02 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 0.305 0.447 0.631 0.794 1.31 1.92 2.55 3.71 6.54 7.93 9.86 12.97 18.05 25.69 33.22 47.02 50.41

37

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Marketing Analysis of Indonesia Concerning Microwave OvensDocumento29 pagineMarketing Analysis of Indonesia Concerning Microwave OvensMindy Wiriya SarikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 6 2Documento60 pagineChapter 6 2Mhmad MokdadNessuna valutazione finora

- Case LETADocumento12 pagineCase LETAJemarse GumpalNessuna valutazione finora

- InvoiceDocumento4 pagineInvoiceJohn WalkerNessuna valutazione finora

- Naxals - Evrywhere and NowhereDocumento4 pagineNaxals - Evrywhere and NowhereSoumik BanerjeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Crisis ManagementDocumento16 pagineCrisis ManagementSoumik BanerjeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Mag Article2Documento5 pagineMag Article2Soumik BanerjeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Rise of Institutional Ism in The History of Economic ThoughtDocumento4 pagineRise of Institutional Ism in The History of Economic ThoughtSoumik BanerjeeNessuna valutazione finora

- EquityDocumento4 pagineEquityZairah FranciscoNessuna valutazione finora

- M 14 IPCC Cost FM Guideline AnswersDocumento12 pagineM 14 IPCC Cost FM Guideline Answerssantosh barkiNessuna valutazione finora

- (Prem) Case Aldi SolutionDocumento17 pagine(Prem) Case Aldi SolutionMir safi balochNessuna valutazione finora

- Currency Converter Currency Name Amount: From United States of American Dollar - USD 100.000 To 77.313Documento7 pagineCurrency Converter Currency Name Amount: From United States of American Dollar - USD 100.000 To 77.313Gomv ConsNessuna valutazione finora

- The IS - LM CurveDocumento28 pagineThe IS - LM CurveVikku AgarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- The External Environment: Opportunities, Threats, Industry Competition, & Competitor AnalysisDocumento63 pagineThe External Environment: Opportunities, Threats, Industry Competition, & Competitor AnalysisLïkïth RäjNessuna valutazione finora

- Questionnare MainDocumento12 pagineQuestionnare Mainmohd junedNessuna valutazione finora

- Wensha Voucher 3 PDFDocumento1 paginaWensha Voucher 3 PDFJulia Shane BarriosNessuna valutazione finora

- 6.3 Output and Growth: Igcse /O Level EconomicsDocumento11 pagine6.3 Output and Growth: Igcse /O Level EconomicsAditya GhoshNessuna valutazione finora

- DK Selling StrategiesDocumento7 pagineDK Selling StrategiesMilan DzigurskiNessuna valutazione finora

- 1546667866verbal Ability qb1Documento46 pagine1546667866verbal Ability qb1Shivam SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Equitymaster's Secrets: The Biggest Lessons From Our Entire 20 Year Investing Journey. .Documento20 pagineEquitymaster's Secrets: The Biggest Lessons From Our Entire 20 Year Investing Journey. .Mithilesh WaghmareNessuna valutazione finora

- Mcrae, Mark - Sure-Fire Forex TradingDocumento113 pagineMcrae, Mark - Sure-Fire Forex TradingJovica Damnjanovic100% (2)

- Liquefied Natural Gas: Not To Be Confused With orDocumento34 pagineLiquefied Natural Gas: Not To Be Confused With orInggitNessuna valutazione finora

- Investment Group Assignment Zaki and LeeDocumento18 pagineInvestment Group Assignment Zaki and LeeLeeZhenXiangNessuna valutazione finora

- Account Summary Amount DueDocumento4 pagineAccount Summary Amount Duedgaborko2544Nessuna valutazione finora

- PRICELINE COM INC 10-K (Annual Reports) 2009-02-20Documento194 paginePRICELINE COM INC 10-K (Annual Reports) 2009-02-20http://secwatch.com100% (1)

- Ross ch22Documento23 pagineRoss ch22Dilla Andyana SariNessuna valutazione finora

- Various Theories Concerning Foreign Direct Investment Economics EssayDocumento9 pagineVarious Theories Concerning Foreign Direct Investment Economics EssayFareeda KabirNessuna valutazione finora

- Amul Vs Baskin FinalDocumento38 pagineAmul Vs Baskin FinalPramod PrajapatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Holly Offshore Sale Notice 20022020 Final New FormatDocumento10 pagineHolly Offshore Sale Notice 20022020 Final New FormatSantosh KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Agricultural Price Policy in PakistanDocumento3 pagineAgricultural Price Policy in Pakistansaeedkhan228880% (5)

- Managing A Stock Portfolio A Worldwide Issue Chapter 11Documento20 pagineManaging A Stock Portfolio A Worldwide Issue Chapter 11HafizUmarArshadNessuna valutazione finora

- Final ProjectDocumento8 pagineFinal ProjectMostafa Noman DeepNessuna valutazione finora

- Datastream Formula PDFDocumento51 pagineDatastream Formula PDFNur Aaina AqilahNessuna valutazione finora

- ICIS World Base Oils Outlook 2020Documento18 pagineICIS World Base Oils Outlook 2020Sameh Radwan100% (1)