Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Seven Years With Louis I. Kahn by Norman and

Caricato da

api-269416530 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

656 visualizzazioni7 pagineNorman and Doris Fisher met Louis I. Kahn in 1960 when they bought a house. They saw him perhaps every two months, on average, over the next Seven Years. They say he worked intensely with yellow paper and black charcoal and in short time a room or home appeared, peopled and landscaped.

Descrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Seven Years With Louis I. Kahn by Norman And

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoNorman and Doris Fisher met Louis I. Kahn in 1960 when they bought a house. They saw him perhaps every two months, on average, over the next Seven Years. They say he worked intensely with yellow paper and black charcoal and in short time a room or home appeared, peopled and landscaped.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

656 visualizzazioni7 pagineSeven Years With Louis I. Kahn by Norman and

Caricato da

api-26941653Norman and Doris Fisher met Louis I. Kahn in 1960 when they bought a house. They saw him perhaps every two months, on average, over the next Seven Years. They say he worked intensely with yellow paper and black charcoal and in short time a room or home appeared, peopled and landscaped.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 7

Seven Years with Louis I.

Kahn

by Norman and Doris Fisher

in Louis I. Kahn Houses by Yutaka Saito

Encounter

It was 1960 when we got to know Louis I. Kahn. Before then,

we had bought a beautiful two-acre suburban lot of trees and a

meandering stream. At first, we had no grand plan in our

search for an architect to design our home. The principals of

one firm which had just finished a major building in

Philadelphia mentioned that they had no financial need to do

private homes but their mentor, Louis I. Kahn, still did them.

We called Mr. Kahn. At that time he had a devoted following

among architects and students, but little appreciation by

those not in the field. He agreed to speak to us and to see our

site. A week later we picked him up at a local train station (as

he didn't drive) and began a wonderful relationship that

lasted until his death in 1974.

We saw him perhaps every two months, on average, over

the next seven years. He came to the house even after it was

built, joined us for meals and even led a mini-discussion

among our friends about our house and his philosophy of

architecture.

On first contact Mr. Kahn did not make an impressive

appearance. He was short in stature and had a badly burned

face from a childhood accident. He wore black jackets,

frequently shiny from wear. These superficialities shortly

faded, as his intellect, energy, humor and warmth showed

through. He worked intensely with his yellow paper and black

charcoal and in short time a room or home appeared, peopled

and landscaped.

We felt we were dealing with a wonderfully practical architect when,

at our first meeting, he asked what rooms we

needed. He wrote them down and when informed of our

budget red-lined the list eliminating a music room, atrium

and conservatory. This was a home for which we budgeted

$45,000 to build, apart from the architectural fee to Mr.

Kahn. In those days, this was a rather low figure for an

architect-designed home.

As a family physician with evening office hours, along

with busy days, it would have been hard to find common time

to meet with a busy architect. However. Mr. Kahn worked late

and our coming in to meet him at 10 p.m. presented no

problem to him. We would ring the bell at his Walnut Street

office. He would lean out the window on the third or fourth

floor that he occupied and drop the keys for us to enter. What

could have been a lethal mass of keys usually dropped beside

us and occasionally into our hands.

A hollowed cinder block on his desk was filled with whole

nuts, and a hammer would assuage what appeared to be his

minimal hunger. On a good day there would he an apple. His

lunches and dinners frequently consisted of food on-the-run.

People speak of him as working all hours and frequently

sleeping at the office.

Endless Pursuit

The plans took us four years and the building three years.

Fortunately, our current home and medical office were very

comfortable and only three blocks away. There was no

urgency to move. The planning especially took so long as he

had many projects, more major than ours, going on simultaneously

in the office. He was doing the Salk Biological

Institute in La Jolla, California, as well as projects in India

and Bangladesh (then East Pakistan). He was in Dhaka or

Ahmedabad for weeks at a time and decisions on our project

often came to a standstill.

In the first set of plans was a handsome stone cube with

the outside walls leaning inward as they ascended. The inside

walls were vertical and described a circle. At the base the

walls were three feet thick. Of course the amount of mass in

the corners was major. The masonry contractor estimated the

cost of this work alone would be $250,000, five times the cost

of the amount budgeted for the entire project.

We had nine sets of plans during the formulation of our

final plans. If we were not satisfied with a set of plans, he

would not modify them but insisted on starting over. For

example, a bridge over a stairwell connecting two bedrooms

could not just be removed. A new plan was necessary. A

medical office originally planned with the house was

discarded during development. Mr. Kahn had a fair number of

home projects that never reached fruition. We are sure that

beside cost overruns, the need to rework his plans created

time problems for his prospective home owners.

Mr. Kahn's office seemed to work with so little concern for

costs that his need for money to run the office was continuous

and frequently acute. On perhaps six or seven occasions, he

sent an employee up by train on a Friday to get a cash

payment for that week's payroll. He would get off the train at

our local stop, receive it and ten minutes later get on the

returning train to town. In fact, we were so concerned about

his borderline financial viability that I asked his associate,

David Wisdom, if he would allow us to have a good friend and

accountant come to his office, at our expense, and put them

on a more secure financial basis. Mr. Wisdom said we were

not the first to have these concerns and offers of help. He

knew Kahn would again decline and suggested we not

mention it to him.

Interestingly, the "finished plans" really were not finished.

After four years we realized Mr. Kahn would rework the plans

forever if we allowed. Our one major reservation was that he

designed only one window, rather small, and set off to the side

in our dining room. The view from the rear of the house looks

down a gentle slope to a stream, with a meadow and woodland

beyond. He felt since the rest of the house was so open to this

view that we would like a cozy enclosed dining room. It

turned out, we did not think so. We felt too enclosed and

knew that woods and the beautiful stream were outside that

wall. Graciously, six months after moving in, Mr. Kahn with

the help of Vinokur and Pace, engineers, redesigned the wall

with a eight-by-ten foot glass window and two functioning

wooden panels. Eating by it now is joy.

In the Purest Manner

Not being architects and looking at the facades as drawn by

the drafts people was a little alarming as they looked rigid and

austere. Our neighbors were intrigued with the building of the

house, though most were concerned and a few alarmed by the

contemporary nature of the building, situated in the middle of

standard suburban architecture. One day, a friend walking by

with his neighbor asked what he thought of the house as it

was nearing completion. He responded he "thought he might

like it when the packing crates come off."

Fortunately we went along with Mr. Kahn's assurances and

ended up delighted with the results. The warm wood, the

strong stone, and the exciting fenestration's made a happy

union.

The home is designed as two cubes, primarily of wood,

with a stone base. The cubes articulate at a 45 degree angle.

The north cube is the "living cube," and has a living room,

dining room and kitchen. It has 18 foot-high ceilings. The

south cube, or the "sleeping cube," has four bedrooms, two

baths, with a powder room on the first floor. A very functional

basement underlies both cubes. We chose cypress for its

resilience to weather and beautiful color. The stone was beige

and gray straight-ended pieces from the local Montgomeryville

quarry.

A prominent feature in this house is the handsome

fireplace and chimney dividing the living room and the dining

room. It forms a massive hemi-cylinder, the flat side with the

hearth facing the living room. His drawings are so complete

that almost all of the stones are drawn, to illustrate size, shape

and positioning. We requested that the mason fit and rout

between the stones to give the impression of a dry wall. It is a

handsome piece of masonry and perhaps, along with his

window seat area, the centerpiece of the house.

"Good building would produce a marvelous ruin." This is

one of Kahn's maxims about architecture. And nothing so

solidified this for us than seeing the picture of the base of our

house during construction. He loved visiting ruins and

sketched many of them, including the French Medieval town

Carcassonne and the Athenian Acropolis.

Ever the poet, Mr. Kahn wanting the non-English speaking

Italian stonemasons to use the stone in a random manner,

explained how to lay the stones multiple times, changing

adverbs each time and got no recognition until he uttered

"crazy" which elicited smiles and gestures of understanding.

The resulting wall with seams all going down to the right gave

one the feeling of being on a pitching ship. Mr. Kahn saw it

and asked for it to be torn down and erected as in a diagram

he drew. The masons promptly quit, but fortunately returned

the next week.

We were determined to stick close to our budget, having

heard horror stories about clients who hadn't done that in

their experience with architects. However, we gave in to

extras when it seemed the return would justify the expense.

The area under the sleeping cube was to be a crawl space for

pipes, though we had wanted more basement space. Mr. Kahn

could not find an aesthetically pleasing way of bringing in

natural light. We pleaded, and he relented, the day before

building was to start. To facilitate building and control the

costs, the builder wanted to employ more economical and

easier ways to enlarge the space, by using steel supporting

beams and posts and cinder block walls. The straightforward

Mr. Kahn said "no, this is a wood and stone house, and the

basement will be wood and stone or I could never show this to

my students!"

Our relationship with Mr. Kahn was a delightful one. His

personality was warm and playful. He was most accepting of

our input and, when not, was careful to explain why not. One

of our lessons came one day when we found the people from

the utility company had decided to put the meters on the front

of the house. I put in a distress call to Mr. Kahn and

suggested perhaps we could put them on the back of the

house. We were informed "THERE IS NO BACK OF THE

HOUSE!" Their placement was settled by recessing them

behind a panel in the shed with small round glass windows to

allow visibility.

We enjoyed being closely involved in the design and

construction process. We made our kitchen purposely small.

Since a couple of clients said kitchens were not his forte, we

asked Mr. Kahn to layout the space for our kitchen which we

then designed. It was so successful that when he redesigned a

center city home for himself and Esther Kahn, he sent his

drafts-people up to copy our kitchen.

Also, we liked the primitive look of white plaster we had

seen in a farm house and wanted the walls inside to have a

similar texture. To produce the same rough-looking finish, we

had a plasterer try to use only the base coat of plaster and an

old fashioned wooden trowel, which gave poor results. We

ended up with a simple plastic trowel and it produced the

texture we desired, leaving a rustic finish on the surface.

We treat the exterior of the house almost like a piece of

furniture. Through trial and error we came up with a regimen

to bring out the beauty of the cypress. About every fourth

year, when the wood is developing a little irregular graying,

we wash and scrub the walls with sodium hypochlorite

(Clorox). The formula is roughly four parts water with one part

chemical. If there is much dirt we may add a little trisodium

phosphate, as a detergent. When dry we use a colorless

linseed oil, such as Cabots 3000. It requires a moderate

amount of effort, but the results are well worth the work and

the expense.

Our two girls grew up in this house and one especially

vivid memory remains for all of us. We gave an "Open House"

cocktail party when the house was just framed in. It was a

glorious October day with the trees dressed in autumn colors.

Our hors d'oeuvres table consisted of a long wooden board set

on two saw horses. An antique commode served as the

"powder room" and paintings hung from studs.

Life-giving Light

Mr. Kahn, in philosophizing about light, said "what is

marvelous about a room is that the light through the window

of that room belongs to the room. And the sun somehow

doesn't realize how wonderful it is until after a room is made.

So, somehow, man's creation, the making of the room, is

nothing short of a miracle ... to think that man can claim a

slice of the sun."

The natural light in our home, varying throughout the day,

is always exciting, and on occasion elevated to that of a

religious experience. When shafts of light pierce the

invaginated windows it gives one the feeling of being in a

cathedral. We never realized until we had this home, how

little consideration is generally given to the kind of light that

enters a house. What an extra dimension his genius created

for us! When Mr. Kahn visited our home a few years after

completion, we asked him how he began our house. He said

"it's really structure. When I put down the places where the

rooms were constructed I was thinking about the light. I

wasn't thinking of beams or studs. I was thinking about what

there is about the structure that will give you light."

Working with Mr. Kahn for seven years has given us a

wonderful architectural education, a very livable unique

house, and remembrance of a warm and special friend. Our

original hope was to build a special home for ourselves, not a

museum or a monument. Living in a Kahn house you didn't

have a choice. Because of that, we have given our home to the

National Trust for Historic Preservation with the hope it will

be preserved unchanged for future architectural students,

architects and historians to study.

Once Mr. Kahn told us he really doesn't design for

specific people. A house has to be suitable for more than one

client. A house, created for a particular family, must have the

character of being good for another family, if its design is to

reflect trueness to form. This statement brought us to a

different realization of how "house" can be defined. We

accepted his premise but still clung to the reality that it had

to work for us. We still continue to marvel at the beauty of its

spaces. Our hope is that others may share in the discoveries

that abound here.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- ABRAHAM, Raimund. Negation and Reconciliation. Perspecta, Vol. 19, p.6-14, 1982 PDFDocumento9 pagineABRAHAM, Raimund. Negation and Reconciliation. Perspecta, Vol. 19, p.6-14, 1982 PDFLídia SilvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Resisting Postmodern Architecture: Critical regionalism before globalisationDa EverandResisting Postmodern Architecture: Critical regionalism before globalisationNessuna valutazione finora

- Gothic Art and ArchitectureDocumento108 pagineGothic Art and ArchitectureJ VNessuna valutazione finora

- The Canadian City: St. John's to Victoria: A Critical CommentaryDa EverandThe Canadian City: St. John's to Victoria: A Critical CommentaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Architecture Norway - An Interview With Sverre FehnDocumento12 pagineArchitecture Norway - An Interview With Sverre FehnRobert BednerNessuna valutazione finora

- Townscapes in Transition: Transformation and Reorganization of Italian Cities and Their Architecture in the Interwar PeriodDa EverandTownscapes in Transition: Transformation and Reorganization of Italian Cities and Their Architecture in the Interwar PeriodCarmen M. EnssNessuna valutazione finora

- Ando Tadao Architect PDFDocumento17 pagineAndo Tadao Architect PDFAna MarkovićNessuna valutazione finora

- BignessDocumento4 pagineBignessSofia GambettaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pelkonen What About Space 2013Documento7 paginePelkonen What About Space 2013Annie PedretNessuna valutazione finora

- Without Within Mark Pimlott 1-29Documento12 pagineWithout Within Mark Pimlott 1-29Negar SB100% (1)

- From Bauhaus To M - (H) Ouse - The Concept of The Ready-Made and The Kit-Built House by Paul J. ArmstrongDocumento9 pagineFrom Bauhaus To M - (H) Ouse - The Concept of The Ready-Made and The Kit-Built House by Paul J. Armstrongshazwan_88Nessuna valutazione finora

- Semiotic Approach to Architectural RhetoricDocumento8 pagineSemiotic Approach to Architectural RhetoricMohammed Gism AllahNessuna valutazione finora

- Abraham 1963 ElementaryArchitecture ArchitectonicsDocumento35 pagineAbraham 1963 ElementaryArchitecture ArchitectonicsjefferyjrobersonNessuna valutazione finora

- Nature in Words and BuildingsDocumento3 pagineNature in Words and BuildingsadinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Louis Kahn EssayDocumento3 pagineLouis Kahn EssayKenneth MarcosNessuna valutazione finora

- Adaptive ReuseDocumento12 pagineAdaptive ReuseManoj KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Eve Blau Comments On SANAA 2010 EssayDocumento7 pagineEve Blau Comments On SANAA 2010 EssayIlaria BernardiNessuna valutazione finora

- Architect: Kathleen James-Chakraborty '78Documento7 pagineArchitect: Kathleen James-Chakraborty '78Moh'd SalimNessuna valutazione finora

- Maki EntireDocumento50 pagineMaki EntirespinozasterNessuna valutazione finora

- AA Files - Anti Ugly ActionDocumento15 pagineAA Files - Anti Ugly ActionCamy SotoNessuna valutazione finora

- Frank Lloyd Wright on the Nature of Materials and Integral ArchitectureDocumento1 paginaFrank Lloyd Wright on the Nature of Materials and Integral ArchitectureGil EdgarNessuna valutazione finora

- ARCH 5110 Syllabus AU14Documento5 pagineARCH 5110 Syllabus AU14tulcandraNessuna valutazione finora

- Wang ShuDocumento7 pagineWang Shunainesh57Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lavin GoingforBaroque 2004Documento29 pagineLavin GoingforBaroque 2004bblqNessuna valutazione finora

- Aureli - 2014 - The Dom-Ino Problem Questioning The Architecture of Domestic SpaceDocumento17 pagineAureli - 2014 - The Dom-Ino Problem Questioning The Architecture of Domestic SpaceArthur RochaNessuna valutazione finora

- Neurourbanism 1Documento20 pagineNeurourbanism 1Marco Frascari100% (1)

- Gottfriend Semper and Historicism PDFDocumento0 pagineGottfriend Semper and Historicism PDFJavier Alonso MadridNessuna valutazione finora

- Hts3 t2 w6 Hejduk Diller Scofidio LectureDocumento36 pagineHts3 t2 w6 Hejduk Diller Scofidio LectureNguyễnTuấnViệtNessuna valutazione finora

- Louis Kahn's Influence On Two Irish Architects Paul GovernDocumento24 pagineLouis Kahn's Influence On Two Irish Architects Paul Governpaulgovern11Nessuna valutazione finora

- Program Primer PDFDocumento12 pagineProgram Primer PDFNicolas Rodriguez MosqueraNessuna valutazione finora

- As Found Houses NarrativeDocumento10 pagineAs Found Houses NarrativeHanjun HuangNessuna valutazione finora

- Sullivan, Louis The Tall Office Building Artistically ConsideredDocumento12 pagineSullivan, Louis The Tall Office Building Artistically ConsideredMarcos MartinsNessuna valutazione finora

- 02 Eisenman Cardboard ArchitectureDocumento12 pagine02 Eisenman Cardboard Architecturebecha18Nessuna valutazione finora

- 3 EricOwenMoss WhichTruthDoYouWantToTellDocumento3 pagine3 EricOwenMoss WhichTruthDoYouWantToTellChelsea SciortinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gottfried Semper's Theory of Art Origins From an Assyrian StoolDocumento11 pagineGottfried Semper's Theory of Art Origins From an Assyrian Stoolvronsky84Nessuna valutazione finora

- Logic of The Image - PallasmaaDocumento12 pagineLogic of The Image - PallasmaaCrystina StroieNessuna valutazione finora

- Carlo Argan - On TypologyDocumento2 pagineCarlo Argan - On TypologyFranciscoPaixãoNessuna valutazione finora

- Tschumi Bibliography: Books, Articles on Renowned ArchitectDocumento17 pagineTschumi Bibliography: Books, Articles on Renowned ArchitectIbtesamPooyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Robert VenturiDocumento14 pagineRobert VenturiUrvish SambreNessuna valutazione finora

- Tim Benton - Le Corbusier y Vernacular Plan PDFDocumento21 pagineTim Benton - Le Corbusier y Vernacular Plan PDFpaul desyeuxNessuna valutazione finora

- Backdrop Architecture Projects Explore Urban Intervention in LondonDocumento10 pagineBackdrop Architecture Projects Explore Urban Intervention in LondonMuhammad Tahir PervaizNessuna valutazione finora

- Kurokawa Philosophy of SymbiosisDocumento16 pagineKurokawa Philosophy of SymbiosisImron SeptiantoriNessuna valutazione finora

- John Pawson Novi DvorDocumento2 pagineJohn Pawson Novi DvorneycNessuna valutazione finora

- Building On The Horizon: The Architecture of Sverre FehnDocumento28 pagineBuilding On The Horizon: The Architecture of Sverre FehnCsenge FülöpNessuna valutazione finora

- Mies van der Rohe's Influence on Five ArchitectsDocumento9 pagineMies van der Rohe's Influence on Five ArchitectsPabloNessuna valutazione finora

- Gustaf Strengell and Nordic ModernismDocumento28 pagineGustaf Strengell and Nordic Modernismtomisnellman100% (1)

- Fumihiko Maki and His Theory of Collective Form - A Study On Its P PDFDocumento278 pagineFumihiko Maki and His Theory of Collective Form - A Study On Its P PDFFauzi Abdul AzizNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Evans Figures-doors-And-passages 1997 PicsDocumento19 pagine10 Evans Figures-doors-And-passages 1997 PicsJelena MandićNessuna valutazione finora

- Interior of House for the Couples in Burgenland, AustriaDocumento6 pagineInterior of House for the Couples in Burgenland, AustriaRoberto da MattaNessuna valutazione finora

- Edrik Article About Tectonic and ArchitectureDocumento5 pagineEdrik Article About Tectonic and ArchitecturezerakNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 CatalogueDocumento63 pagine2014 CataloguequilpNessuna valutazione finora

- Catalan ArchitectureDocumento12 pagineCatalan ArchitectureReeve Roger RoldanNessuna valutazione finora

- James Stirling - Le Corbusier's Chapel and The Crisis of RationalismDocumento7 pagineJames Stirling - Le Corbusier's Chapel and The Crisis of RationalismClaudio Triassi50% (2)

- Neo Classicism& ModernityDocumento11 pagineNeo Classicism& ModernityVisha RojaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Home Is Not A HouseDocumento6 pagineA Home Is Not A HouseNika Dželalija100% (1)

- A Picturesque View of Diffuse Urban SprawlDocumento4 pagineA Picturesque View of Diffuse Urban SprawlReinaart VanderslotenNessuna valutazione finora

- From Architecture to Landscape - The Case for a New Landscape ScienceDocumento14 pagineFrom Architecture to Landscape - The Case for a New Landscape Sciencevan abinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Revitalisation of MuharraqDocumento61 pagineRevitalisation of MuharraqZainab Aljboori100% (1)

- Kimbell Art Museum: Long Span StructureDocumento5 pagineKimbell Art Museum: Long Span StructureNiket Pai100% (1)

- Contoh Descriptive Text About Paris Beserta ArtinyaDocumento11 pagineContoh Descriptive Text About Paris Beserta ArtinyaMarhani AmaliaNessuna valutazione finora

- American Architect and Architecture 1000000626Documento778 pagineAmerican Architect and Architecture 1000000626Olya Yavi100% (2)

- Z Adventure Glove Box Easy Out Bracket Fitting GuideDocumento3 pagineZ Adventure Glove Box Easy Out Bracket Fitting GuideGiambattista GiannoccaroNessuna valutazione finora

- Preschool Arabic WorksheetDocumento12 paginePreschool Arabic WorksheetJo HarahNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To PowerPoint 2016Documento6 pagineIntroduction To PowerPoint 2016Vanathi PriyadharshiniNessuna valutazione finora

- CNU II 12 Piano and Organ Works PDFDocumento352 pagineCNU II 12 Piano and Organ Works PDFWUNessuna valutazione finora

- In The Beginning-Score - and - Parts PDFDocumento45 pagineIn The Beginning-Score - and - Parts PDFGabArtisanNessuna valutazione finora

- Archaeology of The Asura Sites in OdishaDocumento7 pagineArchaeology of The Asura Sites in OdishaBibhuti Bhusan SatapathyNessuna valutazione finora

- Animated Life - Floyd NormanDocumento289 pagineAnimated Life - Floyd NormancontatoanakasburgNessuna valutazione finora

- Construction of Multi-Purpose Building (Barangay Hall) at Brgy Balansay, Mamburao, Occidental MindoroDocumento15 pagineConstruction of Multi-Purpose Building (Barangay Hall) at Brgy Balansay, Mamburao, Occidental MindoroAJ RAVALNessuna valutazione finora

- 09 - Chapter 3 PDFDocumento55 pagine09 - Chapter 3 PDFAditi VaidNessuna valutazione finora

- Platillo VoladorDocumento5 paginePlatillo Voladorfabiana fernandez diazNessuna valutazione finora

- Bhopal (Final)Documento6 pagineBhopal (Final)murtazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Inside Arabic Music f390Documento481 pagineInside Arabic Music f390Patrick Stewart100% (16)

- Geopolitics of The Ideal VillaDocumento8 pagineGeopolitics of The Ideal VillaViorela BogatuNessuna valutazione finora

- GAMABA WeaverDocumento7 pagineGAMABA WeaverDavid EnriquezNessuna valutazione finora

- w03 fcs208 Burn-Lab-Worksheet ShelbyalbrechtDocumento3 paginew03 fcs208 Burn-Lab-Worksheet Shelbyalbrechtapi-595429862Nessuna valutazione finora

- Regional Style ManduDocumento7 pagineRegional Style Mandukkaur100Nessuna valutazione finora

- Town Planning PDFDocumento22 pagineTown Planning PDFMansi Awatramani100% (1)

- D& D5e - (Midnight Tower) - A Most Unexpected Zombie InvasionDocumento13 pagineD& D5e - (Midnight Tower) - A Most Unexpected Zombie InvasionDizetSmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Made in TokyoDocumento20 pagineMade in Tokyoricardo80% (5)

- Searching Music Incipits in Metric Space With Locality-Sensitive Hashing - CodeProjectDocumento6 pagineSearching Music Incipits in Metric Space With Locality-Sensitive Hashing - CodeProjectGabriel GomesNessuna valutazione finora

- My Chubby Pet: SquirrelDocumento12 pagineMy Chubby Pet: SquirrelNastyа Sheyn100% (3)

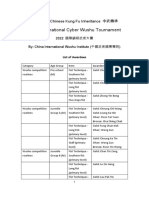

- List of Awardees - 2022 International Cyber Wushu TournamentDocumento11 pagineList of Awardees - 2022 International Cyber Wushu TournamentMOUSTAFA KHEDRNessuna valutazione finora

- Coating Defects Fitz AtlasDocumento73 pagineCoating Defects Fitz AtlasCiprian Iatan100% (2)

- Boys & Girls School Vest Knitting PatternDocumento3 pagineBoys & Girls School Vest Knitting PatternOver LoadNessuna valutazione finora

- Scaffold Erection & DismantlingDocumento6 pagineScaffold Erection & Dismantlingrakib ahsanNessuna valutazione finora

- Scheme Art Grade 1 Term 2Documento3 pagineScheme Art Grade 1 Term 2libertyNessuna valutazione finora

- Nirvanas in Utero PDFDocumento112 pagineNirvanas in Utero PDFtululotres100% (3)

- Interiors / Art / Architecture / Travel / Style: Asia Edition / Issue 30Documento20 pagineInteriors / Art / Architecture / Travel / Style: Asia Edition / Issue 30POPLY ARNessuna valutazione finora