Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Transcending The Technology of Telemedicine

Caricato da

yolandachowDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Transcending The Technology of Telemedicine

Caricato da

yolandachowCopyright:

Formati disponibili

This article was downloaded by: [Macquarie University] On: 04 September 2013, At: 06:25 Publisher: Routledge Informa

Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Health Communication

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hhth20

Transcending the Technology of Telemedicine: An Analysis of Telemedicine in North Carolina

Pamela Whitten , Beverly Davenport Sypher & James D. Patterson Published online: 10 Dec 2009.

To cite this article: Pamela Whitten , Beverly Davenport Sypher & James D. Patterson (2000) Transcending the Technology of Telemedicine: An Analysis of Telemedicine in North Carolina, Health Communication, 12:2, 109-135, DOI: 10.1207/ S15327027HC1202_1 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327027HC1202_1

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is

expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

HEALTH COMMUNICATION, 12(2), 109135 Copyright 2000, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Transcending the Technology of Telemedicine: An Analysis of Telemedicine in North Carolina

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

Pamela Whitten

Department of Telecommunication Michigan State University

Beverly Davenport Sypher

Department of Communication Studies University of Kansas

James D. Patterson II

Department of Communication University of Kansas

This study investigated the telemedicine program at East Carolina University School of Medicine. In-depth interviews, organizational texts, and archival records provided data for a case study that sought to understand what telemedicine is to organizational members and how they came to create this contextual reality. The goal of this study was to apply interpretive paradigmatic assumptions in the privileging of telemedicine as the very context of the organization. The findings explain how organizational members make sense of this new way of providing health care. Organizational members talk revealed that telemedicine is multifaceted: It is access, an economic tool, education, technology, and a grant activity. With the single exception of technology, these themes emerged equally, regardless of whether the telemedicine provider was located at the urban hub site or the rural spoke site. Interestingly, members at both locations talked about critical events in relation to receipt of grant or financial support for new projects. Implications for future research are advanced.

People who live in rural or remote areas simply do not have the range of health care services available to their neighbors in more urban areas. Estimates reveal that there are more than 28 million Americans living in medically underserved rural communities (Office of Technology Assessment, 1990). This population is served

Requests for reprints should be sent to Pamela Whitten, Department of Telecommunication, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 488241212. E-mail: pwhitten@pilot.msu.edu

110

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

by health care systems plagued with professional isolation, limited access to specialists, inadequate numbers of primary care physicians, declining hospital use, discontinuity of care when patients are transferred to tertiary centers, financial difficulties, and trouble recruiting and training physicians (Kane, Morken, Boulger, Crouse, & Bergeron, 1995). Although levels of severity differ, virtually all rural communities share similar problems. Ironically, the very people who need health care the most have the least access to specialized care. Telemedicine offers one possible solution to some of the problems that currently plague rural health care. More than 2 decades ago, Park (1974) defined telemedicine as the utilization of interactive or two-way television to provide health care. In only a few years, Bennet, Rappaport, and Skinner (1978) expanded the concept with the term telehealth, which included education, administration, and patient care. Since its inception in the early 1970s, telemedicine programs have been springing up at a record pace, with the number of North American programs doubling each year since 1993.1 In the United States alone, federal financial support for telemedicine exceeded $85 million in 1994 (Perednia & Allen, 1995). Perednia and Allen (1995) argued that even though there is increasing evidence that managerial and administrative issues play a vital role in the effectiveness and utilization of telemedicine services, we have paid too little attention to the influence of leadership, organizational, and training factors on the success or failure of modern telemedicine programs. The new technology has for the most part overshadowed the creative and recreative human aspects involved in accomplishing the task for which it was developed. What we do not yet understand are issues related to the socially constructed realities of these telemedicine organizations and how they come to be understood and managed. The context has created new ways of organizing, replete with age-old issues of organizational power and influence, definitions of the situation, members roles in the social situations they create, and relationship development and maintenance. The purpose of this study is to demonstrate how communication plays a central role in the creation and maintenance of a telemedicine organization. This case study focuses on the telemedicine program of Eastern Carolina University (ECU) School of Medicine. The research goal is to determine what organizational members perceive telemedicine to be, how they understand and describe how tele1The rapid growth and high visibility of telemedicine projects hide an important issue: Relatively few patients are being seen via telemedicine. In 1993, the average number of patientphysician consultations was about 200 per program among the 10 North American interactive mediated programs. Typically, these were composed of about four linked remote sites. If the most active program, which saw 1,000 patients in 1993, is excluded, then the average drops to fewer than 150 consultations per program in that year. Preliminary figures for 1994 suggested that underutilization continued to be a problem (Allen & Allen, 1995). In almost every telemedicine program, teleconsultation accounts for less than 25% of the use of the system (Perednia & Allen, 1995). Instead, the majority of online time is used for medical education and administration.

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

TELEMEDICINE

111

medicine gets done, and what they understand to be the critical events leading to the origin and evolution of their program.

DEVELOPMENT OF TELEMEDICINE Telemedicine techniques have been under development for the past 4 decades. Wittson and colleagues were the first to employ telemedicine for medical purposes in 1959 when they set up telepsychiatry consultations between the Nebraska Psychiatric Institute in Omaha and the state mental hospital 112 miles away (Wittson, Affleck, & Johnson, 1961). In the same year, Montreal, Quebec was the site for pioneer teleradiology work (Jutra, 1959), and in the 1970s, there was a flurry of telemedicine activity. Several major projects developed in North America and Australia, including the Space Technology Applied to Rural Papago Advanced Health Care project of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in southern Arizona; a project at Logan Airport in Boston, Massachusetts; and programs in northern Canada (Dunn et al., 1980). The 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s exhibited a series of telemedicine pilot and demonstration projects. With the exception of the 20-year-old telemedicine program at Memorial University Hospital of Newfoundland, none of the programs begun before 1986 has survived (Grigsby & Kaehny, 1993). However, the 1990s have proven to be a period of rapid growth. In 1990, there were 4 active telemedicine programs. In 1994, there were 26 such programs, and by March 1998, there were over 150 telemedicine programs (Allen & Grigsby, 1998). The creation of many of these programs was sparked by clinical needs in rural areas. Although data are limited, early reviews and evaluations of these programs suggest that the equipment was reasonably effective at transmitting the information needed for most clinical uses and that users, for the most part, were satisfied (Conrath, Puckingham, Dunn, & Swanson, 1975; Dongier, Tempier, Lalinec-Michaud, & Meunier, 1986; Fuchs, 1974; Murphy & Bird, 1974). However, when external sources of funding were withdrawn, the programs simply folded. Whereas Perednia and Allen (1995) attributed the failures to costbenefit analysis, other researchers pointed to limited physician acceptance (Michaeis, 1989). How telemedicine comes to be defined and organized is yet another explanation of how, and if, it will be sustained. The implementation of telemedicine raises important questions about just what it is, how it can be used, and how it can be incorporated into national and local health care systems. Firsthand observations of viable programs provide baseline data for understanding how this new technology has created a new health care context. It is becoming increasingly clear that funding levels are just one of the many dimensions across which telemedicine programs differ. Although we know a good deal about the hardware that makes telemedicine possible, we have just begun to

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

112

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

investigate how communication with and about this technology produces the organizational structures that make it possible. To understand the organizational aspect of telemedicine is to acknowledge the communicative foundation for organizing in general and accomplishing telemedicine in particular. More specifically, how we talk about telemedicine reveals the reality we have constructed. Thus, how organizational members frame, discuss, and label telemedicine appears important to understanding this context. Telemedicine was generally designed to serve remote areas, so differences in perspective are likely to exist between those serving and those served. We cannot understand the telemedicine context without understanding both perspectives. Equally important is how organizational members view and enact telemedicine. These assumptions guided the development of the following research questions (RQs): RQ1: What are recurring themes in organizational members descriptions of telemedicine? What are recurring themes in organizational members descriptions of the purpose and goals of telemedicine? RQ2: Do themes and terms differ between telemedicine providers in rural and urban sites? Do themes and terms differ by type of work performed or position? RQ3: How do organizational members describe how telemedicine gets delivered?

METHODS AND PROCEDURES Telemedicine lends itself to qualitative study, as it desperately needs what Van Maanen (1979) referred to as a descriptive focus. To date, most telemedicine research has had a technological focus. We know a good deal about bandwidths and resolution but little about the human dimensions that make the practice possible. To understand how organizational members come to understand their organization, we looked for distinct patterns of assumptions, norms, and values by employing a case study strategy that analyzed interviews, organizational texts, and archival data. As a method, the case study provides a chunk of reality (Lawrence, 1953, p. 215) or a touchstone of reality (Haytin, 1988, p. 41) that is epistemologically in harmony with the readers experience (Stake, 1978, p. 5) and make[s] visible the qualitative features of organizational life (Sypher, 1990, p. 3). This case study attempted to answer how and why a specific telemedicine organization developed the way that it did. It addresses a contemporary problem that has potential relevance transferable to other health contexts. Through the use of multiple methods, this case focused on the way communication shapes and reflects what a telemedicine organization is.

TELEMEDICINE

113

Interviews For this case study, the researcher conducted 25 in-depth interviews with study participants. The researcher interviewed all key staff employed in the ECU telemedicine office, including the director, scheduler, technician, grant manager, and clerical staff. In addition, the researcher interviewed four of the most active consulting telemedicine physicians. Of the 25 interviews, 12 were conducted in North Carolina. Of these 12 North Carolina interviews, 10 were conducted face-to-face in a private office with three physicians, two administrators, two technicians, a scheduler, and a clerical staff member and 2 interviews were conducted privately over the telemedicine system with two remote site nurses. The remaining 13 interviews were conducted via telephone. These phone participants included six rural nurses, four rural physicians, one rural physicians assistant, and an ECU physician and technician. The interviews ranged in length from 20 min to 2 hr; not surprisingly, the interviews with physicians tended to be the shortest. All respondents agreed to be recorded, and interviews were transcribed verbatim. A focused, open-ended interviewing structure was chosen so that respondents could introduce ideas (Mishler, 1986), the researcher could discover how people think and what unique perspectives they hold (Patton, 1990), and to encourage the participants to name their own worlds (Mishler, 1986). A general interview guide was employed as a framework for all of the interviews (see Appendix for the interview guide). Over 20 hr of interviews produced almost 400 pages of text for analysis.2 The 400 pages of text from the 25 transcribed interviews were content analyzed for themes, a single assertion about some subject (Holsti, 1969, p. 116). Themes were mutually exclusive, multiple indications of the same theme were counted only once, and elaborations of the themes determined its categorical fit. Holsti explained that application of the theme as the unit of analysis is appropriate for research that is attempting to gauge beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions. In line with the goal of privileging the voices of the organizational members, a

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

2With the addition of DS3 links over an asynchronous transfer mode (ATM) network, this is the only telemedicine program in the world operating simultaneous T1 lines, microwave, and DS3 ATM links. The host site of this telemedicine program (the ECU School of Medicine) has constructed four individual 6 12 ft modules to give the consulting physician a soundproof area to interview a patient located at a remote site. The physician sits at one end of the module and uses two-way interactive video, audio, and digitized data. The modules house a camera, monitor, close-up or graphic monitor, microphone, lights, diagnostic tools, graphic camera, and a direct-line telephone. The rural or remote telemedicine sites utilize existing clinic space in the remote hospital or clinic. All facilities of a remote clinic are present with the addition of camera, monitor, close-up or graphic monitor, microphone, lights, diagnostic tools, graphic camera, facsimile, digital data, and a direct-line telephone. The presenting health provider (physician assistant or registered nurse) uses two-way interactive video, audio, and data, and has a direct interface to all equipment used for the transmission.

114

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

theme was captured in a phrase or several sentences. Two coders independently sorted 20 units into five thematic categories resulting in a 90% intercoder reliability and a Cohens kappa of .86.3

Organizational Documents and Archival Records Organization documents provide historical data, long-lasting information, and information available only in written form. Because documentary evidence is likely to be relevant for every case study topic (Yin, 1994), the researchers requested a sampling of all documents from the telemedicine program, but an examination of the departments files produced very few examples. What was available was used to corroborate and augment the evidence gathered during the interview phase. Organizational documents examined in this study included a mix of proposals, user monthly reports, and Web pages. Archival records were also collected for this case study to verify interviewee reports of activity within the telemedicine programs life. Archival records examined included organizational records, maps and charts, lists of provider and patient names, and procedures.

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

Telemedicine Program at the ECU School of Medicine The telemedicine program at the ECU School of Medicine was chosen as an important point of inquiry for several reasons. First, the telemedicine program is fairly new but is established enough to have some stability in routine, procedures, and staff. Second, the demographics of North Carolina make it an ideal area to study the

3Several rules were created for coding these themes. First, all themes were mutually exclusive with no data being coded into more than one theme. The decision was made to count a theme one time for an individual member, even when multiple statements were made that fell under that themes classification, because interviewees repeated the same description of telemedicine at different points throughout the interview. For example, the theme access was only counted one time when the same person described telemedicine at one point during the interview as the way we make it easier for the patient to see the doctor and then later described telemedicine as something that has really increased their (patients) chances to be seen by a specialist. A third rule concerned which theme to privilege if more than one was made in the same statement. This rule was defined in response to the many statements, which included mention of the technology involved. It was decided that these statements would only be coded as technology if no other description of telemedicine were provided. For example, when a respondent described telemedicine as a telephone with a little videoits just a videophone, the statement would be coded as technology. However, when another respondent described telemedicine as a mechanism by telephone lines that patients can receive treatments at outlying centers without going to the actual medical center, it was coded as access because the respondent elaborated beyond just the mention of technology.

TELEMEDICINE

115

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

growing problems of rural health care, because this region is one of the most unhealthy in the nation.4 In 1991, the North Carolina Department of Corrections invited all of the medical schools in North Carolina to participate in a telemedicine project that would not directly benefit most citizens of eastern North Carolina but, if it worked, could be used as a model for the health access problems facing other sections of the population. After careful consideration, the ECU School of Medicine was the only medical school in the state that accepted the invitation. Administration at the ECU School of Medicine decided to house telemedicine within the Center for Health Sciences Communication. In 1992, the ECU School of Medicine began providing telemedicine consultations to the North Carolina Department of Corrections at Central Prison in Raleigh, North Carolina, located 100 miles away. Telemedicine was implemented as a cost-effective way to bring medical specialists into the prison by avoiding the need to transport the patients outside the prison system with the associated risk, eliminating the cost for two guards and a state vehicle. The prison telemedicine project ultimately spurred the development of procedures, technology, and protocol for deployment of telemedicine into rural hospitals and clinics in North Carolina. It also provided the background against which future understandings were created. Physicians see and talk to patients via the telemedicine link and then diagnose and prescribe medications when necessary. Physicians and nurses also have access to digital stethoscopes, a graphics camera, and a miniature, handheld dermatology camera to aid in patient examinations. As of the time of this study, more than 500 patient consultations and more than 200 continuing education programs have been provided via telemedicine for the prison and rural outreach sites. A unique aspect of the ECU telemedicine program is the assortment of network and hardware that have been integrated.5

4Specifically, eastern North Carolina is one of the most unhealthy regions in the nation. In 1988, for example, North Carolina had the countrys highest infant mortality rates. Yet, eastern North Carolinas infant death rate was even worse than the states average and was 28% higher than the U.S. rate (9.9/1000 live births, U.S.; 12.2/1000 live births, North Carolina; 12.7/1000 live births, eastern North Carolina). Death rates for heart disease and cancer are higher in eastern North Carolina than in the state as a whole; only 3 counties in the region are below the states rates. The worst rates in North Carolina for death due to diabetes, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, and nephritis are found in this eastern, 29-county region. 5Validity and reliability of interview data are sometimes challenged because the researcher is influencing the type of information obtained (Patton, 1990) by the questions she has selected to ask and by affecting what actually occurs during an interview. In an effort to enhance both the reliability and validity of the interview date, this investigator employed several steps. First, all responses were considered within the special context that existed for each interview interaction (Fitch, 1994; Mishler, 1986). Second, the researcher attempted to minimize any fear that respondents might have about reprisal by management for any responses by assuring participants that they were permitted to participate in the research and that the confidentiality of their responses was of the highest priority to the researcher (Mishler, 1986).

116

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

The actual planning of North Carolinas telemedicine program began in 1991, and the first patient was seen in 1992. Almost everyone was aware of the prison project that led to the birth of telemedicine. As one respondent explained, the prison contract is credited as being the project that enabled telemedicine to be born and allowed ECU to grow telemedicine to meet its mission of serving eastern North Carolinato help meet the demand of primary care physicians in the rural area and the total isolation that a lot of them feel. What is interesting in these descriptions of the origin is the implication that ECU is the bastard or last-choice medical school in the state. It was the last choice of the Department of Corrections, yet ironically it proved to be the innovative program willing to try something new. One urban member said, What I told you earlier I think is very significant about Duke and Chapel Hillneither of them wanted to work with the prison to do telemedicine, so they came down east to the stepchild. In 1993, the programs directorship was expanded to include a physician. One year later, ECU received a grant from the Health Care Finance Administration (HCFA) to bring on two rural telemedicine sites in Williamston and Ahoskie. Respondents explained that these two sites were selected because ECU had a standardized residency program already established there. An urban physician stated that in addition to attending rounds via the system and then once or twice a week theyre [the residents] also precepted or they have network meetings with their instructors back here (at ECU). This urban physician also explained that the residents benefited in sitting in on those consults referred to specialists because its an opportunity to learn from the consultation not just send your patient to so and so and get a letter back, but participate in the consults. Additional grant funding in 1995 made it possible to add three new sites. In a few years the telemedicine program included six remote sites. It became obvious to the participants of this telemedicine program that someone was needed to supervise and manage all of the grants, making this growth possible. Once hired, the new grant manager outlined in a memo the teams first tasks: We have begun to formally define the roles/responsibilities of the rural telemedicine coordinators (RTCs) (per RTC meeting on 9/27). This will be very beneficial to all of us (GO Team and RTCs). It is now time we do the same for ourselves. While the operation of the grants has been clicking right along with no major problems, I feel WE can take grant operations to an entirely different level with a better understanding of our individual and corporate roles and responsibilities. Part of the RTCs new responsibilities included looking for additional business. The technical projects ECU tackled were also critical incidents in the progress of the program. One was dubbed the docking station. As one interviewee explained

TELEMEDICINE

117

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

What were saying is lets look forward ten years and see what really makes sense on the network. Well, Im convinced everything were doing right now is wrong. The way were doing it is right in that it fits the need today, but this whole thing is going to end up on the Internet delivery system. Thats whats going to make it work in the home. Thats whats going to bring the cost down, so what we can do now that gets us there quicker. So we start developing these vision pieces the docking station which are these centers that have input devices and can collect every piece of information at one place, at one time the vision is that all this stuff is interconnected I think we can fast forward this thing light years. I think the stuff were doing right now is what we have to do to get through the next two to three years, but lets not get stuck in this shitbecause this aint right. Thus, urban practitioners find themselves with a host of critical incidents that have shaped who they are and what they do. With these turning points comes the implicit understanding that the essence of telemedicine will continue to be constructed and reconstructed by what they do and say. In the next section we discuss the specific findings of this case study analysis. RESULTS Taken together, analyses of interviews, organizational documents, and archival data were cataloged according to purpose. Information within these texts was compared to data provided from the interviews. The results of these analyses supported and corroborated the results from the interview data. To understand how these organizational members view a telemedicine program, the following section is organized around the three RQs proposed. RQ1: What are recurring themes in organizational members descriptions of telemedicine? What are recurring themes in organizational members descriptions of the purpose and goals of telemedicine? Five distinct themes emerged to answer this question. Participants described telemedicine as access, an economic tool, education, technology, or a grant activity. The access category contained all references to telemedicine as the availability of health care to patients who would not have had access or convenience without telemedicine. An economic tool was the theme that captured all perceptions, which explained telemedicine as an entity that offered an economic advantage or solution. Education encompassed all perceptions of telemedicine as providing educational opportunities for health providers. Technology served to include all descriptions of telemedicine as strictly hardware or telecommunications. Finally, a grant activity included all perceptions that telemedicine exists in accordance with the grant funding that secured its beginning.

118

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

Telemedicine as Access Every participant talked about telemedicine as access for patients or residents of remote areas. For the purposes of this analysis, the access theme encompassed all responses that described telemedicine as the source of care that would otherwise be unavailable or difficult to attain. Access was commonly talked about in relation to a place. The overwhelming feeling that telemedicine represents a place is evidenced by the fact that almost all of the respondents discussed telemedicine in this way. However, this notion of place had several meanings for organizational members as is evidenced in the language they used: Care was either emanating from a place (the medical center) or being delivered to a place (a rural site). In one sense of place, the provider at the urban site is the focal point. As various interviewees explained, telemedicine is reaching out, connecting, linking, or carrying health care from the medical center to those in need. For these respondents, the medical center (as the provider) is the privileged sense of place. Other respondents claimed that telemedicine allows patients to leave their local town without actually leaving town. One respondent explained that telemedicine may be the only way they [patients] get out of town. A rural respondent also illustrated this perspective by stating that telemedicine has allowed patients to reach specialists who dont come here to our hospital. A second conception of access placed telemedicine in the rural or remote health care facility. Telemedicine is seen as health care services at home or in the remote community that would not otherwise have access to medical care. Participants talked of telemedicine as moving the specialist or the medicine to the patient without anyone having to drive, without them having to come to us, without the specialist having to worry about making a living in that area. In this way, telemedicine was a way for people to stay at home in their communities with their health care providers in their offices. Thus telemedicine as access can be located at the remote site or the hub site, or both. Even though there were differences in real space, every single organizational member described telemedicine as access located in a place. Many participants made reference to both places when describing telemedicine as access. Telemedicine as an Economic Tool For 80% of the respondents, telemedicine was a tool for economic advantage. These economic benefits ranged from discussion of direct financial rewards to acknowledgment of benefits that ultimately could result in financial gain through either revenue generation or cost savings. In terms of direct cost savings, respondents described telemedicine as a reduction in (patient) transfer which is what HCFA is trying to preach eliminating redundancy in medical testing and avoiding duplication of services when two

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

TELEMEDICINE

119

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

providers are talking to each other. As one participant explained, the prison prides itself to be the most pressing evidence of a cost-effective delivering of health care using telemedicine. Keeping patients in town was also viewed as a potential way to save money for the health care system: I think with telemedicine you really could manage someones care and keep them in the community and save the overall system a whole lot of money, said one participant. Another economic advantage was saving dollars by catching illnesses before they are too advanced. An urban physician stated that telemedicine will save the system money in that patients who would not normally see a specialist til they were dying could be saved early by telemedicine catching and intervening early. In addition to saving health care dollars, telemedicine was also described as an economic opportunity. For example, telemedicine could increase revenue for rural hospitals by keeping patients: Its just a matter of keeping them [patients] in their own county and keeping their dollars there. Urban respondents mentioned this same perspective: The main goal is to keep the university productive, or from the hospitals viewpoint, they see it as a way to bring in more patients to extend their catchment area. Several respondents implicitly, if not explicitly, said they saw telemedicine in terms of dollars or increasing utilization. One rural nurse hoped telemedicine would bring more clients into her facility: But definitely they [her urban hospital] see more of an avenue with public health in the area and having it more utilized by public health making referrals to us. After learning of the potential for child psychiatric consultations via telemedicine, one rural nurse excitedly anticipated an increase in consults: I kind of got excited because I think Ive found an area that maybe we can increase consults. Telemedicine as Education Sixty-four percent of the respondents talked about telemedicine as something that benefits them educationally. Worth noting is the direction of the educational opportunities. Regardless of the type of education discussed later, all respondents talked about telemedicine as education for health care providers in rural or remote areas. One comment that exemplifies this unidirectional learning came from an urban physician who said In fact, its immediate CME [continuing medical education6] for the referring physician. You teach them the way you think. You teach them how you would approach this, what you would do and then what you would recommend. He can ask you questions right there.

6Continuing medical education refers to the continuing education required by all physicians to maintain their licensure.

120

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

Respondents views of the educational opportunities provided by telemedicine range from formal continuing education to serendipitous learning through participation in telemedical activities. Unfortunately, however, urban physicians and other health providers did not mention the educational opportunities from which they might benefit. Just like access, providers saw education as flowing from the hub out. In terms of the formal education, respondents explained that telemedicine provides continued education required for health practitioners to maintain their licensure and exposure to grand rounds from ECU. One rural physician explained that telemedicine is an avenue for receiving vital information to stay abreast of all the medical changes that are going on. An internal newsletter dated February 1996 explained that telemedicine allows for easy delivery of continuing education course work and special programming such as lectures and forums at the School of Medicine. Telemedicine was also given credit for serving as a formal educational resource for the residents located at two sites that have a rural residency program. One urban physician explained that the purpose of telemedicine is to support the rural residency program. One urban organizational member even claimed that the telemedicine program would not really be possible the way its set up now without telemedicine. A rural physician stated that telemedicine existed to facilitate the residency program. I think that anything over that is gravy. Another way telemedicine supports the medical residents is by enabling them to participate in complex consults. One ECU support member explained, I can put them in front of the camera and my instructor on the other end can say right on or dead wrong. Lets rewind and look at this again. So it became a real tool for them. Telemedicine was also credited with serendipitous educational results. One urban physician explained that telemedicine gives the more isolated physicians the opportunity to interact with their specialist peers and to learn from that experience. In the same vein, a rural physician stated that I learn a lot when we discuss a case. Its improved my horizon. Another rural physician cited the educational benefit because they learn from communicating with other physicians. One rural nurse saw an educational benefit for her because when youre at a clinic such as we are, you dont get exposure as far as the different things that you do in a hospital. [Telemedicines] increasing my nursing skills a whole lot from where they may have been. Thus, telemedicine as education means (a) formal educational programs to rural physicians and residents and (b) experiential learning that results from participating in health encounters. Telemedicine as Technology Just over half of the organizational members described telemedicine solely as a piece of hardware or telecommunication link. The support staff located at ECU

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

TELEMEDICINE

121

takes great pride in their creativity and technical prowess. One member stated, Were such a creative bunch we can do things like this coast-to-coast ATM that took tons of work and all sorts of creative problem solving. An internal memo from the Dean of the School of Medicine stated, ECUs Telemedicine program has been widely recognized nationally and internationally for its innovative application of technology in healthcare. Several of the comments describing telemedicine as technology seemed to reflect this pride. For example, toward the end of an interview, one urban physician told the interviewer that Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013 The thing about our program we havent talked about that is unique is the hybrid nature of our technologies so we have four technologies and thats been a real challenge to get all those pieces to talk to each other. In general, there was much talk of technology across themes. However, most who mentioned any technology did so in conjunction with a benefit such as access or education. However, half of the respondents discussed telemedicine strictly in terms of the technology at least one time during their interview. Telemedicine as a Grant Activity A little less than half of the telemedicine providers described telemedicine in terms of the grant that served to actually bring telemedicine to their facility. All of the telemedicine sites in this study were funded solely by a federal grant, except for the prison site, which is totally funded by a state contract. It is not surprising then that telemedicine is often thought of as a grant. Because of the funding, several respondents expressed concern about the survival of their telemedicine program. One urban physician stated that all was fine as long as the grant money is there, but once that grant money starts drying upyoure not going to be funded indefinitely. Youve really got to have some sort of game plan if you want to keep the system for making sure somehow it supports itself. An urban support staff member expressed frustration with the grants and money piece of this: Here were four years into this and if I walked away right now this is over. This does not have a life of its own and thats really frustrating. An urban physician thinks telemedicines destiny is in the organizations hands. He claimed that when the grant money is done, if we havent done our homework right, the whole system will collapse. If we have done our homework right, it will fit right into managed care. The terms of the grant also impact how telemedicine actually gets delivered. One rural nurse explained that one drawback in the grant occurred because they

122

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

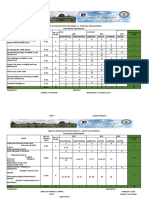

put [that] you had to be an RN or higher to actually [present] the patient consultations. This presents a problem because in rural areas RNs are hard to find to do that. Another grant condition that certainly impacts telemedicine concerns payment; the grants pay for all patient consults. Several of the rural coordinators use this condition as a selling point to persuade patients to use telemedicine. One referring rural provider thinks that telemedicine will not be used as frequently once the grants end. We really do have a lot of poor people here So having a free consult with a specialist, theyre saving several hundred dollars by getting that service without having to pay for it. Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013 RQ2: Do themes and terms differ between telemedicine providers in rural and urban sites? Do themes and terms differ by type of worked performed or position? Perceptual Differences Based on Location Urban and rural respondents were fairly consistent in their interpretations of telemedicine. All respondents described telemedicine as access. The only exception was the focus on the technology. More than 75% of the urban respondents saw telemedicine as technology, whereas only 31% of the rural respondents described it that way. Because personnel at the hub site either are engineers or work closely with them, it is not surprising that more hub participants would talk about telemedicine as technology. To determine if rural participants talked about each telemedicine theme significantly more or less than urban participants, chi-square analyses were performed for each of the five themes. Only one theme, technology, emerged as significant, 2(1, N = 12) = 4.16, p < .05. Table 1 displays the distribution of units among rural and urban participants and results of the chi-square analyses.

TABLE 1 Distribution of Themes Among Rural and Urban Respondents Respondents Rural Theme Access Economic took Education Technology Grant activity

a 2

Urban % 100 69 69 31 46 Number 12 10 7 9 6 % 100 83 58 75a 50

Number 13 9 9 4 6

of 4.16, p < .05.

TELEMEDICINE

123

Perceptual Differences About Process The ECU physicians had a much narrower explanation for the process of delivering telemedicine, which centered on their involvement with a consult. For the urban physician, the process seems to be encapsulated to fit around the specific telemedicine role. There was virtually no discussion of the pieces of this process that are taken care of by other members of the telemedicine organization. When asked specifically to name the people who work with the physician to perform telemedicine, three of the four physicians named the two program directors and the scheduler. Only one of the physicians also named the technicians as well as acknowledged a person on the remote end. The support telemedicine staff from the rural or remote sites responded from a different perspective from their urban counterparts when asked to walk through a case. Interestingly, six of the eight respondents (75%) did not provide a delineated sequence of events for providing telemedicine. Instead, they picked a recent patient and narrated how telemedicine was done to these patients. RQ3: How do organizational members describe how telemedicine gets delivered and how is this different from traditional health care? Almost without exception, respondents confidently discussed the process of delivering or doing telemedicine. Not surprisingly, each of the support staff at ECU spoke about the process of doing telemedicine in great length. This group alone collectively provided more than 20 pages of interview text about how they do telemedicine. What is similar across their responses is the step-by-step procedures they described, even though the interviewer simply asked them to give her a case and tell her what happens.

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

Comments About the Process The most commonly acknowledged problem mentioned by almost half of the respondents concerned scheduling. A 1995 internal memo documented the problem: Problems getting Telemed consult requests to the coordinator. Continues to be a problem from the scheduling office. A rural physician said the hardest part is setting up a time when the consultant and the physician on our side are together. In addition to schedule problems, there were also complaints about the inflexibility of the current scheduling process. One rural physician expressed that the telemedicine process would be better if telemedicine would work on the basis that I would get an instant referral to anyplace at any time. I mean not to any place, but the necessary subspecialist

124

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

at any time. If I would see a patient today and I would tell you OK, we have got another opening in an hour where you will be seen by telemedicine too. That would be something I would like because then I would be able to settle the issue in one setting. A little more than one third of the respondents complained about technical difficulties. As one respondent said, there are a whole host of technical problems. Never works all the time. It does not work when all the dignitaries are here to see it work. Another respondent talked about equipment glitches. There was also frustration about getting health providers encouragement. Almost 30% of the organizational members discussed the challenges they faced in trying to persuade physicians and patients to accept telemedicine as a viable health care alternative. One urban support member explained, Telemedicine is in its infancy, and therefore nobody knows how to do it or what they should be doing. Another urban support member talked about doctors not being real excited about the system. Having to convince them that there is good in it and it can work in their favor. A final problem mentioned by three telemedicine providers concerned the expectation that they do so much work. One rural nurse said, Probably my biggest complaint is the amount of time. If I had somebody who could help with this even on a half-time basis that would be fine. About 15% of the respondents stated that performing the actual consult was the easiest part. One urban physician claimed its going in there, sitting down in the room, talking, its not hard. Theyve made it easy. Two respondents claimed that the easiest part was actually making the referrals. The management difference, however, was seen as one of a personal context. Even though most respondents placed a beginning and an ending to the telemedicine consult, their descriptions of the process and its attendant problems evidences an understanding of the complexities and ongoing processes involved in making telemedicine possible. Very few (10%) felt that telemedicine was only interaction via video. Theoretically, one staff member pointed out, its just management of disease. Not surprisingly, 60% of all respondents specifically mentioned the lack of hands-on care, and another 20% mentioned that the doctor and patient are not physically together. Their examples regarding this major difference were not subtle. For example, some respondents acknowledged that they had to rely on other health providers in ways they would not have to in a traditional consult. As one urban physician explained If we see a scaly lesion on the face, we want to know if its thickening or not. We have lost that capability and we rely on the people on the other end. Of course, if its someone we know and trust, we rely on them more than if its somebody we dont know.

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

TELEMEDICINE

125

In addition to the clinical information denied from physical presence, some physicians pointed out the relational disadvantage of providing care at a distance. One physician stated that its against everything that were taught as far as touching the patient hands on developing that kind of rapport with the patient the stuff that were taught is part of being a doctor. Others viewed the lack of touch as the limiting factor for telemedicine. Another physician explained how telemedicine changes the actual consult interaction: Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013 And the big thing Ive noticed was how much I glance when Im talking to Mrs. Smith. Im looking at her arms and looking at her face and looking for skin cancers or a rash. Telemedicine is much more pointed. You talk to the patient and then you break off and say, Ok, I need to look at her, or show me her cheek and you lose that sort of incidental quality and it becomes very pointed. On the other hand, one urban support member felt that Rather than being impersonal, in some ways it can be more personal the [consulting] doctor is here. Hes not going to be distracted by other things . I found that doctors wanted to take more time and speak over the network. I think theyre so concerned in establishing a personal relationship that they spend more time with clients. Rural nurses saw similar potential benefits because there are providers at both ends, physicians talk more, and more people are involved overall. One felt that in order for telemedicine to work better we have to develop ways that the information flow happens a lot better. A rural nurse explained the following: Granted, the physician who is on the telemedicine gets to ask anything he or she wants but that physician generally does not have access to as much of the medical record as someone who would see our patients in person. As one rural physicians assistant stated, there are certain kinds of things you cant do through telemedicine. Hands on kinds of things so there is always going to be a place for actual in-person referrals.

DISCUSSION In part, this project has been an adventure in exploring organizational sense making. The researchers have sought to gain an understanding of how telemedicine pro-

126

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

viders structure the unknown (Waterman, 1990, p. 41); how they (organizational members) construct what they construct, why and with what effects (Weick, 1995, p. 4). This study reveals many important lessons about the invention and contextualizing of telemedicine in North Carolina. Taken together, the results of this study indicate how and why individuals organize this particular telemedicine program. The differences between rural and urban practitioners understanding of telemedicine suggest more deeply rooted conceptions of health care delivery and particularly telemedical health care. This technology appears to have created a hierarchical context, constructed with a sense of place where people are acted on versus acted with, in which new kinds of relationships are formed with unique relational demands and in which ground and figure both literally and figuratively constantly shift. The communication possibilities and contrast demand our attention. Hierarchical and Unidirectional Conception of Telemedicine Talk from people at both rural and urban sites evidenced a rather hierarchical, unidirectional conception of telemedicine. They all agreed that it begins at the rural center, but power resides at the urban hub. Given the hub-and-spoke metaphor that characterizes this innovation across programs, the perceived power is rather predictable. Even though the consult is initiated at the rural sites, the specialty physicians think they control all activities. They control scheduling functions at their own hub site, as a telemedical event cannot take place until it fits into their schedules. They provide the expertise during a medical consult to the patient at a remote site. They also pass down their wisdom by educating health providers at remote sites. Nobody talked of potential insight and information that remote providers could share with specialty physicians. In essence, this telemedicine activity is thought to emanate from the hub site via the consultants. Rural support staff are implicated as less powerful in this hierarchy. The rural telemedicine coordinators report (at least 50% of the time) to the grant operations manager at ECU. They are told how to schedule consults, how to collect feedback, and what to do during the 20 hr per week they devote to telemedicine. For the most part, power and control can be found in Greenville, the urban hub of North Carolina. Burrell (1988) explained that power and control do not reside within things (such as technology); they reside in a network of relationships which are systematically connected (p. 227). Time will tell how these relational networks will change. Perhaps the referring physicians will flex their muscles as they come to recognize that they are the true gatekeepers. After all, most of these people told us that telemedicine actually starts with the referring physicians decision to send a patient to a specialist. Although on the surface it might look as if the rural sites have no power to initiate change, a deeper reading suggests they actually hold the key to the existence of this organization.

TELEMEDICINE

127

A Sense of Place North Carolinians descriptions of telemedicine activity were filled with a sense of place. They situated telemedicine delivery in a remote clinic or in the tertiary medical facility. One is either fortunate enough to have the convenience of staying at home or privileged enough to receive the quality of care that is found at a tertiary facility. There is not yet a new sense of a place in which health encounters occur. Perhaps this is because patients and providers still must physically sit in a medical facility to do telemedicine. As we watch telemedicine shift into the home (Allen, 1995), perhaps these perceptions will be altered, but for now telemedicine is as much a sense of place as it is a new technology.

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

Acted On Versus Interacted With Within this context, telemedicine emerged as something that is done to people. Szasz and Hollender (1993) acknowledged the traditional notion of health delivery where the doctorpatient relationship depends on what the doctor does. With a nontraditional medium, things do not appear to be much different. In the hills of eastern North Carolina, specialists do telemedicine to patients. Patients are acted on, not interacted with. From their explanations, one would not expect particularly high levels of patient satisfaction with telemedicine, but research does not bear this out. According to Allen et al. (1994), telemedical patients are moderately satisfied. Other research has shown that patients also are often satisfied with the traditional medical care they receive from providers. However, they are less than pleased with the warmth (Daly & Hulka, 1975), level of friendliness (Korsch & Negrete, 1972), or interpersonal involvement and expressiveness (Street & Wiemann, 1987) of physicians. Research already has demonstrated that patients are unhappy with the traditional way that medicine gets done to them, but they are generally satisfied with the medical care. This telemedicine seems to be no exception, even though this study does point to the possibility of more patient involvement and more physician interactions.

New Relationships The telemedicine providers in North Carolina organize telemedicine in a manner that appears to change relationships and communication practices in seemingly positive directions. Some physicians are enticed by the notion that their patients do not disappear into a black hole when they refer them to a specialist. Instead, with telemedicine, the rural physician can actually be present during the specialty consult and obtain immediate feedback about the patients condition. The telemedicine

128

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

context also sets the scene for the development of new relationships. Health communication research has shown us that effective health care relationships provide many health-related benefits, whereas the failure to establish vital relationships can actually hinder the accomplishment of health care delivery goals (Cline, 1983; Kreps, 1988). With telemedicine, referring and consulting physicians can meet face-to-face and come to know one another. Only through telemedicine can a referring physician actually come with a patient to his or her specialty consultation. Telemedicine sets the scene for a give-and-take of information and support between physicians and other health providers. Patients can also bring in their families to participate in consults resulting in relationships between physician and family member. Some physicians at ECU were incredulous at the new way they were doing medicine in the telemedicine context. Doing telemedicine means trusting in ways never taught in medical school, they said. Suddenly, a physician must rely on the touch of a health provider he or she does not work with closely. Suddenly we see a mammoth contextual difference between traditional and telemedical care: Telemedicine as a context can only exist with this trust as a core component.

A Shifting Context Health providers in North Carolina have also created a context for telemedicine that seemingly holds a higher standard than required for the practice of doing traditional medicine. We saw this displayed in frustration expressed about scheduling and coordinating information transfer. For some reason, this context expects patient information to be more accessible via telemedicine than traditionally. The created context dictates that any physician who has less than total knowledge about all aspects of a patients health should be frustrated with this system. Yet, what health provider in traditional medicine has access to this type of information? The process of faxing or mailing patient records can be complex and exceedingly slow in traditional medicine. Yet, the telemedicine context dictates higher expectations of almost instantaneous retrieval, and the expectation is that this happens before, during, and after the consult. Initially, telemedicine in North Carolina was about doing consults within a prison setting. Suddenly a medical director was hired, and telemedicine was about outreach and education. New sites were established, and telemedicine became a process of scheduling and coordinating. A grant operations manager came on board, and telemedicine became a GO Team project. The impending onset of managed care came crashing into North Carolina, and telemedicine became a solution for the financial constraints of medicine. The director of the telemedicine program had a vision for a docking station, and telemedicine became the mechanism to transition medicine into the next century for North Carolina.

TELEMEDICINE

129

This case study has provided story after story of how organizing has impacted the people who do the organizing, whereas the people who do the organizing have simultaneously impacted the very organizing process (Giddens, 1979). Within development of this context, it is simply impossible to separate the individuals from the organizing process. For example, more than 60% of the consults performed at ECU have been done by a handful of dermatologists who are telemedicine champions. Much of this context would have been different if the physician champions at ECU had been emergency physicians. The process of scheduling and coordinating telemedicine simply would not be the same. These health care providers warned us in their own way not to expect this context to remain static. They told us that they were looking for more members and more types of applications as well as more business. They told us that they were concerned about the plight of this organization when grant monies disappeared. They told us they were keeping an eye toward tomorrow as they do telemedicine today. They also joyfully bragged about their accomplishments and their fun of communicating like the Jetsons. They tantalized us with their excitement and worried us with their frustrations. They taught us that to understand the microaspects of delivering telemedicine, we must understand the macroaspects of organization. But we must heed their caution that this context is constantly changing. It is important to note that contextual change does not just happen because time passes. One must look to symbolic interactionist theory (Mead, 1934) to understand that contexts are social in nature and change through social interactions. From an interactionist perspective, human beings continuously rely on communication to create and transform complex worlds of interaction. Contextualization is the active and interactive creation of context through human interaction (Lutfiyya, 1987). Because social context is both socially constructed and fluid, it must be assumed that the telemedicine program located in North Carolina is going through a continuous process of recontextualization. This case study illustrated the inseparability of communicating and organizing. Communication is not just some vehicle that facilitates the life cycle of an organization. Instead, communication serves as the foundation of the organizing process. The creation, maintenance, and understanding of telemedicine at ECU occurs through relationship building, shared constructions of hierarchies and power structures, the development of trust between providers that enables telemedicine activity to actually occur, and the creation of expectations that guide the norms and membership roles for mutually acceptable delivery of this service. Indeed, it is through communication, through the sharing of evolving understandings of telemedicine, that these organizational members perform the continuous process of organizing. Perhaps the most important lesson provided by this case study is the reminder that we can study specific contexts, we can get excited about new technologies and

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

130

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

organizations, but we can never stray too far from the universal role played by communication. It is through communication that we mutually create understandings about innovations such as telemedicine and ultimately come to organize ourselves to perform as an organization. Communication is the basis for trust, relationship development, power and hierarchy issues, development of job norms and role expectations, and how we arrive at shared understandings of what our organizations are. To understand any phenomenon, we must understand how people organize, how they make work orderly. Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

IMPLICATIONS Because of the descriptive nature of this study, specific implications for future telemedicine research became evident. This section seeks to engage the readers inquiry by providing specific examples of those things that make telemedicine different and how these examples may serve to impact traditional medicine. The purpose of this research project in some ways transcends telemedicine and can be applied to any health care or technological study. Clearly, we need a better understanding of telemedicine, or any health delivery system, in terms of its organizational or social context. Conrath, Dunn, and Higgins (1983) issued a warning to future telemedicine researchers: A technology does not stand alone. Neither should it be evaluated alone. Its use takes place in a social context and has an effect on that system. To assume otherwise, or to assume the consequences are irrelevant, or to assume that they can only be good, is to place man as the servant of machine. Conscious effort has to be made to ensure that the situation is the reverse. (p. 201) This study has held as its premise that to privilege the technology of telemedicine over the context of a telemedicine organization would be a grave mistake. In line with this approach, telemedicine should be viewed in a new way. Rather than talking about telemedicine in the traditional manner as the delivery of medical services via telecommunications technologies, this study creates a new dialogue in which telemedicine becomes many things ranging from access to a grant activity. The study of other health care technologies in this manner offers the potential for a new understanding of the health services we have available to us. Results from this study illustrate the potential role the telemedicine context may play in our changing expectations of health care. The organizational members in this telemedicine program indicated through their comments a shifting in the very paradigm of health delivery. Taken further, these results indicate that the process of communicating telemedicine is actually shifting the health care paradigm. Traditional medicine may alter as a result of new relational expectations suggest-

TELEMEDICINE

131

ing new solutions and presenting new problems for health care. For example, having referring and consulting health providers both present during a consult complicates the scheduling of a telemedicine event. At the same time, it enhances learning and potentially improves health care. Also, the literal dependence by a consulting physician on the hands of the rural medical presenter has necessitated the need for consultant and practitioner to dedicate time to know one another, so that the practitioner comes to understand what the consultants hands would do and feel; thus, they develop trust and a sense of the other. Because of these relational shifts, the dynamics of the medical encounter as we currently understand it may ultimately shift and change who has control. To suggest that telemedicine may play an important role in shifting perceptions of what health care is and how it should be done has profound implications on the future direction of telemedicine research and perhaps health communication research more generally. First, it necessitates a more contextual approach to the study of health care. For example, mass media are often credited with reducing the entire world to a virtual global village. However, if we look back before this time of national town meetings, we find evidence of local town meetings where participation and interaction were key (Wiezenbaum, 1991). Second, telemedicine may alter the current modes of social behavior in health care. This could take the form, as exemplified through ECU, of health providers who traditionally did not work with one another, forming relationships that strengthen patient care by truly facilitating a team approach to health care. Or perhaps, telemedicine will lead to changing expectations that will impact providerpatient communication. Will the patient only develop a relationship with the health provider actually touching him or her? Research looking at telemedicine from the patients perspective will be needed to fully understand this reinvention. Perhaps patients will eventually care little about ever being in the same room as a physician. Perhaps they will sacrifice a physicians touch for the convenience and immediacy of being able to see their physician from their own home or the collaborative team efforts possible and necessary through this medium. If the contextualization of telemedicine does lead to a recontextualization of health care, communication researchers will play a vital role in explaining how health care is reinvented through changing social interactions and expectations. In short, traditional medicine may take on a new face as health providers absorb new relational elements into their delivery of medicine and patients create a new understanding of what constitutes a medical encounter. Practical Implications for Telemedicine Practitioners The results of this analysis indicate several practical implications for telemedicine practitioners. First, the success of telemedicine programs depends largely on well-defined roles and responsibilities. For example, the perceived beginning and ending points discussed in the article guided job roles and responsibilities as they de-

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

132

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

termined the scope of job functions for each individual. In this program, participants indicated that doing telemedicine meant much more than turning on the equipment. It indicated that someone had to educate providers about potential issues of telemedicine and that they had to schedule consults and persuade users, both physicians and patients. Second, the results of this study indicate that context plays a crucial role in the success of telemedicine programs. Thus, organizations must choose leaders who fit well with the goal and mission of the program, or who construct goals and missions and choose team players willing to and able to accomplish them. Is the goal of the telemedicine program programmatic or protocol? Programmatic goals focus on service and demand leaders with medical and administrative backgrounds. Protocol goals focus more on technical features and demand leaders who possess strong technical skills. Finally, the results of this study indicate that conducting health care via telecommunications changes managers supervisory roles. For example, nurses at rural sites do not work formally for the urban doctors conducting the sessions. Issues of control and direction change as a result of providing telemedicine, and these issues indicate that managers also must change how they supervise individuals who do not formally work for them. In addition, these results indicate telemedicine programs increase levels of interdependency among health care providers. Thus, training should focus on establishing trust between providers and on aiding managers in dealing with these control issues. In this study, access emerged as an important feature of telemedicine programs, indicating that traditional notions of structure often do not apply. Telemedicine links facilities and people that normally are not linked by the formal structure. Practitioners need to develop training systems and adopt management practices that focus on the informal structures that emerge from doing telemedicine and likewise reexamine new structures that emerged through these interactions. At its premise, this study adopted the assumption that an organization does not precede communication and subsequently become supported by it. Instead, an organization is simultaneously born through communication and constructed by it. This study sought to document this phenomenon by identifying the context of a specific telemedicine organization. Organizations and communication can no longer be viewed as mutually exclusive. Instead, they are inextricably intertwined and can be understood through the context that evolves from their unity. Much like Dewey (1916) argued, Society continues to exist not by communication, by transmission, but in communication, in transmission (p. 4). REFERENCES

Allen, A. (1995, September). Home healthcare via telemedicine. Telemedicine Today. Allen, A., & Allen, D. (1995). Telemedicine programs: 2nd annual review reveals doubling of programs in a year. Telemedicine Today, 3(1), 1014.

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

TELEMEDICINE

133

Allen, A., & Grigsby, B. (1998). Consultation activity in 35 specialties. Telemedicine Today, 6(5), 1834. Allen, A., Williamson, S. K., Sadasivan, R., Wittman, C., Cox, R., & Thomas, C. (1995). A teleoncology pilot study: Physician acceptance. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 1, 3437. Bennet, A. M., Rappaport, W. H., & Skinner, E. L. (1978). Telehealth handbook (PHS Publication No. 793210). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Burrell, G. (1988). Modernism, postmodernism, and organizational analysis 2: The contribution of Michel Foucault. Organization Studies, 9, 221235. Cline, R. (1983). Interpersonal communication skills for enhancing physicianpatient relationships. Maryland State Medical Journal, 32, 272278. Conrath, D. W., Dunn, E. V., & Higgins, C. A. (1983). Evaluating telecommunications technology in medicine. Dedham, MA: Artech House. Conrath, D. W., Puckingham, P., Dunn, E. V., & Swanson, J. N. (1975). An experimental evaluation of alternative communication systems as used for medical diagnosis. Behavioral Science, 20, 296305. Daly, M. B., & Hulka, B. S. (1975). Talking with the doctor, 2. Journal of Communication, 25, 148152. Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: Macmillan. Dongier, M., Tempier, R., Lalinec-Michaud, M., & Meunier, D. (1986). Telepsychiatry: Psychiatric consultation through two-way television: A controlled study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 31, 3234. Dunn, E., Conrath, D., Acton, H., Higgins, C., Math, M., & Bain, H. (1980). Telemedicine links patients in Sioux lookout with doctors in Toronto. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 22, 484487. Fuchs, M. (1974). Provider attitudes toward STARPAHC, a telemedicine project on the Papago reservation. Medical Care, 17, 5968. Fitch, K. L. (1994). Criteria for evidence in qualitative research. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 58, 3238. Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory: Action, structure, and contradiction in social analysis. Berkeley: University of California Press. Grigsby, J., & Kaehny, M. (1993). Analysis of expansion of access to care through use of telemedicine and mobile health services. Report 1: Literature review and analytic framework. (Available from the Center for Health Policy Research, Denver, CO 80222). Haytin, D. L. (1988). The validity of the case study. New York: Peter Lang. Holsti, O. R. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Jutra, A. (1959). Teleroentgen diagnosis by means of videotape recording. American Journal of Roentgenology, 82, 10991102. Kane, J., Morken, J., Boulger, J., Crouse, B., & Bergeron, D. (1995). Rural Minnesota family physicians attitudes towards telemedicine. Minnesota Medicine, 78, 1923. Korsch, B. M., & Negrete, V. F. (1972). Doctorpatient communication. Scientific American, 227, 6674. Kreps, G. (1988). The pervasive role of information in health and healthcare: Implications for health communication policy. In J. Anderson (Ed.), Communication yearbook 11 (pp. 238276). Menlo Park, CA: Sage. Lawrence, P. R. (1953). The preparation of case material. In K. Andrews (Ed.), The case method of teaching human relations and administration (pp. 215242). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Lutfiyya, M. N. (1987). The social construction of context through play. New York: University Press of America. Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, & society (Vol. 1). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Michaeis, E. (1989). Telemedicine: The best is yet to come some experts say. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 141, 612614. Mishler, E. G. (1986). Research interviewing: Context and narrative. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

134

WHITTEN, SYPHER, PATTERSON

Downloaded by [Macquarie University] at 06:25 04 September 2013

Murphy, R. L. H., & Bird, K. T. (1974). Telediagnosis: A new community health resource. American Journal of Public Health, 64, 113119. Office of Technology Assessment. (1990). Healthcare in rural America (OTA Publication No. H434). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, #05200301257. Park, B. (1974). An introduction to telemedicine: Interactive television for delivery of health services. New York: Alternate Media Center, New York University. Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Perednia, D. A., & Allen, A. A. (1995). Telemedicine technology and clinical applications. Journal of the American Medical Association, 273(6), 483488. Stake, R. E. (1978). The case method in social inquiry. Educational Researcher, 7(3), 58. Street, R. L., & Wiemann, J. M. (1987). Patient satisfaction with physicians interpersonal involvement, expressiveness, and dominance. In M. L. McLaughlin (Ed.), Communication yearbook 10 (pp. 591612). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Sypher, B. D. (1990). Case studies in organizational communication. New York: Guilford. Szasz, T. S., & Hollender, M. H. (1993). The basic models of the doctorpatient relationship. In B. D. Ruben & N. Guttman (Eds.), Caregiverpatient communication: How to read an organization (pp. 112). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt. Van Maanen, J. (1979). Reclaiming qualitative methods for organizational research: A preface. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 522. Waterman, R. H., Jr. (1990). Adhocracy: The power to change. Memphis, TN: Whittle Direct Books. Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Whitten, P. (1996). Transcending the technology of telemedicine: A case study of telemedicine in North Carolina. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence. Wiezenbaum, J. (1991). Computers, tools, and human reason. In D. Crowley & P. Heyer (Eds.), Communication in history: Technology, culture, society (pp. 273282). New York: Longman. Wittson, C. L., Affleck, D. C., & Johnson, V. (1961). Two-way television group therapy. Mental Hospital, 12, 223. Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.