Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Or Journal

Caricato da

Israel Soria EsperoDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Or Journal

Caricato da

Israel Soria EsperoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Original Article

Operating room nurses perceptions of the effects of physician-perpetrated abuse

inr_767 321..327

B.L. Higgins1

RN, MN

& J. MacIntosh2

RN, MSc(A), PhD

1 MN Student, 2 Professor, Faculty of Nursing, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, N.B., Canada

HIGGINS B.L. & MACINTOSH J. (2010) Operating room nurses perceptions of the effects of physician-perpetrated abuse. International Nursing Review 57, 321327 Background: Operating room (OR) nurses experience abuse perpetrated by physicians; however, little research has been conducted to examine nurses perceptions of the effects of such abuse. Aims: The aim of this research was to understand participants perceptions of physician-perpetrated abuse on their health and ability to provide patient care. Materials/Methods: In this qualitative descriptive study, ten operating room nurses working in Eastern Canada participated in open-ended, individual audiotaped interviews that were transcribed for analysis using Boyatzis method for code development. Results: Three categories of factors contributing to abuse were developed. The rst, culture of the OR, included environment and hierarchy. The second, catalysts of abuse, included nurses positions and experience as well as non-nurse factors such as resources and interpersonal relationships among physicians. The third category, perceived effects, included psychological, physical and social health consequences for nurses. Effects on patient care consisted of safety and potential challenges to access. Discussion: Nursing practice implications included mentoring, support and accountability for action. Educational implications related to interdisciplinary education and increased education on communication, assertiveness, and awareness of abuse. Implications for research included studying perceptions of other health-care providers including physicians, studying recruitment and retention in relation to abuse, and studying other abuse in health care such as horizontal violence. Conclusion: We suggest a proactive approach for empowering OR nurses to address abuse and an increased focus on interdisciplinary roles. Keywords: Eastern Canada, Effects of Physician-perpetrated Abuse, Health Effects of Abuse, Operating Room Culture, Physician-perpetrated Abuse

Introduction

Workplace abuse in any form is counterproductive for everyone involve. Workplace abuse is a generic term used to describe unacceptable behaviour towards others, and has been studied using many terms: physical, psychological and sexual abuse, harassment, and violence. Workplace abuse can occur in any profession

Correspondence address: Barbara L. Higgins, 2797 Route 845, Carters Point, NB, E5S 1S9, Canada; Tel: 506-648-7445, Fax: 506-648-6799; E-mail: higbl@nbnet. nb.ca.

or work sector (Chenier 1998; Elliot 1997); however, health-care workers are 16 times more likely to experience abuse (Elliot 1997), with abuse of nurses accounting for 24% of all professions affected (Di Martino 2000, 2002). Recent research focuses on workplace abuse in health care and consequences for nurses and for patient care (Deans 2004; Rosenstein 2002), and the effect of abuse on organizations and the health-care system (Gerardi 2004; Kerr et al. 2005). Although abuse of health-care personnel is perpetrated by patients, families, peers and physicians (Duncan et al. 2001), this study focuses on abuse of nurses by

2010 The Authors. International Nursing Review 2010 International Council of Nurses

321

322

B. L. Higgins & J. MacIntosh

physicians in operating rooms (ORs). The purpose of this research was to understand OR nurses perceptions of the effects of physician-perpetrated abuse on their health and their ability to provide patient care.

the organization lead to many unnecessary costs that direct resources from the clinical area (p.182). No studies that explored OR nurses perspectives of experiencing physician-perpetrated abuse were found.

Background

The OR is a dynamic, exciting, technical and intense workplace. OR nurses require knowledge of surgical procedures, nursing processes and require excellent organizational skills. They often work in conditions that challenge their concentration. OR nursing is mentally, emotionally and physically demanding. and the additional strain created by abuse can often be insurmountable for nurses. The OR is an environment that differs from other clinical areas. While nurses in other settings focus their attention on direct patient care and planning, OR nurses have a brief yet important period for patient care prior to anaesthesthia, with most time spent facilitating surgery. Time spent with physicians is usually one-to-one, for eight to twelve hours. Nurses must stay in the theatre to ensure patient safety. Close contact over long uninterrupted workdays creates potential for abuse. Workplace abuse is common and detrimental to workers and organizations. Nurses are three times more likely to experience psychological, physical and sexual abuse from patients and families, peers, and physicians compared to other professions (Di Martino 2002). Psychological abuse includes emotional and verbal outbursts such as belittling, yelling, condescension and ignoring, while physical abuse includes shoving, hitting, throwing instruments and kicking. Sexual abuse can be a threat or actual acts of abuse (Anderson 2002). Nurses surveyed in 2001 (n = 8780) from 210 Canadian hospitals reported that in the past ve shifts they worked, 46% experienced different types of abuse including emotional abuse, threat of assault, physical assault, verbal sexual assault and sexual assault. Sources of abuse included patients, families, co-workers and physicians, with emotional abuse the most frequently reported (Duncan et al. 2001). Soeld & Salmond (2003) conducted a study with American hospital nurses (n = 461). Of the respondents, 91% reported experiencing verbal abuse in the preceding month with physician as the most frequent source. Workplace abuse is a well-documented cause for employee illness and stress (Chenier 1998; Henry & Ginn 2002), decreased job satisfaction and increased turnover rates (Manderino & Berkey 1997), low morale (Rosenstein 2002), low productivity and high absenteeism (Henry & Ginn), poor organizational image, and poor patient care (Deans 2004). Abuse decreases productivity resulting in lost wages, increased absenteeism, property damage, and legal and medical expenses (Chenier 1998). Gerardi (2004) stated, The effects of unresolved conict on clinical outcomes, staff retention and the nancial health of

Method

The purpose of this study was to explore OR nurses perceptions of the effects of physician-perpetrated abuse on their health and their ability to provide patient care. We used the qualitative descriptive method that encouraged nurses to share experiences using everyday language more readily capturing responses not available using other methods (Sandelowski 2000). To initiate conversations, we used open-ended questions beginning with an invitation to describe experiences of physician-perpetrated abuse. Ten registered nurses from Eastern Canada participated in this research. Criteria included female nurses who were working or had worked in an OR at the time of their abuse and who were comfortable communicating in English. Following ethical approval from the university Research Ethics Board, we arranged for the nursing regulatory body to send recruiting letters to OR nurses randomly selected from their stratied registration list. Other nurses were contacted using the snowball method. Of the ten participants, eight had over 10 years OR experience. Three had left the OR and were working elsewhere or were actively seeking work elsewhere. Ages ranged from 28 to 58 with the majority over 50 years old. Nurses worked in nine different facilities, ranging from community to regional, with a variety of surgical specialties. Condentiality for both nurses and hospitals prevents providing more details. Interviews were audio-taped, transcribed and analyzed using Boyatziss (1998) method and criteria for close reading, developing codes and creating relevant categories. Initially, each researcher coded the same interviews. We then reviewed codes, discussing interpretations. A third researcher was invited to review the codes and to offer critical appraisal. After an agreement on codes was reached, one researcher coded the remaining interviews. Analysis involved reading and internalizing each participants statement, assigning codes and later combining similar codes into categories. Data saturation was reached following ten interviews. After completion of the nal interview, I shared a summary of the ndings with the nurse who conrmed that they resonated with her experience. A summary of ndings was provided to all participants.

Findings

Categories generated from the data were: OR culture, catalysts of abuse and the effects of physician-perpetrated abuse. The majority of abuse reported by nurses was perceived as psychological, including being belittled, ridiculed, yelled and sworn at. Some

2010 The Authors. International Nursing Review 2010 International Council of Nurses

Effects of physician-perpetrated abuse

323

nurses experienced physical abuse, including being kicked, pushed and having objects thrown at them. No one discussed sexual abuse.

The operating room culture

The OR culture was governed by rules, policies and procedures, restricted access, and patients that were, for the most part, anaesthetized. This culture was one of seclusion, specialty and privacy. Two elements formed a picture of OR culture: the environment and hierarchy. The environment included aspects of technology, proximity and pride. Nurses shared how new surgical advancements are continually introduced so that even experienced OR nurses were perpetually learning. They found that managing continuous learning in this highly technical specialty, adhering to strict standards of practice, policies and procedures, working with many surgeons and anaesthetists, and caring for patients were often stressful. Bull & FitzGerald (2006) noted, [Nurses] must continually adapt their knowledge and skills to the new equipment and adjust to the changing values and expectations that accompany the equipment and associated advances in surgical ability and outcome (p. 6). Physicians expectations to work with experienced nurses added to challenging situations. One nurse shared, You can tell that they are annoyed by the way that they are acting, with how they are breathing, how they are sighing. She added, No one wants to work with someone thats annoyed . . . you are doing the best you can from the level of training that you have to work with that person. OR nurses and physicians often work in close proximity during critical situations for long periods of time. Nurses commented that they were required to stay in the room for the full shift regardless of events. One nurse recalled losing condence early in the day after being chastised for a task that she felt was completed correctly: . . . if you do something rst thing in the morning you still have eight hours with this person, that they are watching you and you already know that it is not good enough . . . This aura of seclusion and the inability to leave the room fostered an environment conducive to, and which lacked consequences for, abuse. Nurses noted that the environment limited their ability to quickly nd someone for assistance. As one nurse shared, You cant just go pull someone from another room. Theyre busy as well. Nurses expressed an overwhelming sense of pride in their work and profession. Even though time spent with conscious patients was limited, nurses spoke of their roles importance in patient care. One nurse stated, I know that the time that I spend with the patient is quality time and I know that I make a difference in their experience.

Distinct hierarchy separating nurses from physicians is the second element related to culture. Many nurses reported being part of an OR team, yet not feeling fully included. One participant reported working alongside two physicians who were involved in a conversation, from which she was excluded. I was embarrassed by their conversation. They were talking about things that I was feeling uncomfortable about. I had to disengage. Another nurse reported being the brunt of a bad mood and being made to feel that the physician was above her. Hierarchy was apparent when one nurse shared how she initially defended her peers in abusive situations but developed a trouble maker reputation in the eyes of physicians and peers alike. She later conformed to the culture, allowing abuse to go unreported, resulting in her re-acceptance in the group. She shared, You would stand up for what is right and you would get punished for it. Hierarchy was evident when trying to resolve issues between physicians and nurses. Nurses spoke of reporting abuse to administration and feeling their complaints went unheard. One nurse shared, If a doctor says something against a nurse, who do you think [administration] are going to believe? Nurses talked among themselves about incidents stating that they felt that their reports failed to go beyond the administrators attention. Although everyone in the OR was aware of abusive incidents, other departments in hospitals and those in the upper management were unaware. Consequently, some nurses used strategies to try to gain control over their environment such as trying to keep ahead, pleasing physicians and making sure that everything was perfect. One nurse shared, I think that the biggest thing is learning what pushes their buttons in a good way or bad way and using that to our advantage. Tanner & Timmons (2000) reported a more relaxed OR atmosphere between nurses and physicians, and Riley & Manias (2005) reported an OR environment where guards were let down and often suppressed feelings surfaced.

Catalysts for abuse

This category included two areas: the position and experience of the nurse, and the contextual factors related to abuse. Although abuse was reported throughout nurses careers, two points appeared signicant: nurses new to the OR and nurses in charge. Contextual factors related to initiating abuse were apparent throughout nurses careers. Nurses recalled the experience of being new to the OR as stressful and confusing even without physician-perpetrated abuse. Nurses discussed acquiring the knowledge required to feel competent to work in the OR and how learning was an arduous process, often not supported by physicians. Dialogue between physicians and nurses was often absent, Why cant [physicians] just tell me what is wanted instead of holding out their hand?

2010 The Authors. International Nursing Review 2010 International Council of Nurses

324

B. L. Higgins & J. MacIntosh

and [The physician] stomps around the table and makes you feel stupid because the abdominal sponge was too wet. Some physicians would take time to teach but others would wait for, as one nurse described, opportunities to watch you drown. One nurse reported that physicians seemed to identify nervousness and feed off that and do things to make nurses feel uncomfortable. As one nurse shared, . . . if you are weak and physicians see it, they will walk all over you. One nurse still felt like a new nurse after 3 years working in the OR. In many hospital units, this length of time would be sufcient to be considered a competent nurse. This contrasting view attests to the amount of technology and knowledge each nurse requires before becoming an effective OR team member. The second career point occurs when nurses are in charge of the OR. Being in charge, either as managers or charge nurses, places experienced nurses in challenging positions between physicians and staff. On these occasions, the responsibility for the health and safety of the staff can conict with physicians expectations. Being in the middle, charge nurses felt responsible for all issues. Charge nurses reported that policy enforcement was challenging. Ensuring policy compliance is a standard that OR nurses were legally required to comply with, yet one that caused friction with physicians. Abusive responses often resulted when physicians were reminded about practice, kept waiting to ensure policies were followed or informed about scheduling problems. A nurse recalled events in relation to a policy: I did approach [the physician] and told [the physician] that the particular task was not followed according to hospital policy and [the physician] went ballistic. Even though physicians were aware of policies, reactions were often perceived as aggressive. Contextual factors were those non-nurse situations that nurses perceived were triggered by events beyond their control. Non-nurse catalysts were events that occurred throughout nurses careers and included challenges with resources and interpersonal relationships between physicians. Nurses perceived that they became targets of abuse because of these factors even though they had no control over them. Nurses reported contextual factors such as rooms running late because of complications or inaccurate bookings, potential cancellations, lack of supplies or instruments and instrument failure, and lack of surgical beds. Lack of operating time was a catalyst for abuse in many facilities. Often, physicians blamed nurses for causing delays, even though delays may have occurred because of inaccurate bookings. One nurse felt rushed by a physician, Come on, come on, if you dont hurry with that count, my next case will be cancelled. Nurses often felt pressured to rush to complete their tasks at a time when they felt that concentration and attention to details were critical to ensure patient safety. Worries about demands for increased speed and productivity conicting with patient safety were

reported by Alfredsdottir and Bjornsdottir (2008) in a research conducted at a university hospital in Iceland. Another non-nurse factor is related to relationships among physicians. On some occasions, nurses reported being situated between physicians who were not compatible. Lack of respect for one another was displaced to the nurses. One nurse said, Knowing the history of these two physicians, I felt his outburst did not warrant what he felt that I did wrong. Another nurse shared, Unfortunately as nurses we tend to take the brunt of [issues between physicians] as it is directed at us instead of dealing directly with each other. Another nurse felt that nurses in the OR were safe targets for physicians to release frustrations on when problems occurred. The experience of abuse had common characteristics among nurses regardless of hospital location. Nurses shared roles, standards of practice and titles of OR nurses, and although though they worked in different locations, their experiences were similar.

The effects of physician-perpetrated abuse

Nurses perceived negative psychological, physical and social effects of physician-perpetrated abuse to their health, and they also noted effects on patient care.

Perceived effects on the nurse

Nurses perceived negative psychological, physical and social effects of physician-perpetrated abuse to their health. Nurses described immediate effects of physician-perpetrated abuse as psychological and often reported feeling worthless, lacking condence and judging and second-guessing their own abilities. They reported developing feelings of insecurity and guilt, and often felt disrespected. One nurse reported, Once you start feeling not condent with what you are doing, you start making more mistakes. Another nurse reported, You do something wrong and all you can focus on is that one mistake. You arent able to focus on your job. Another nurse felt belittled in front of peers and felt inadequate for the rest of that day. I felt horrible. I felt like I was two years old, and I questioned myself if I knew what I was doing? Anderson (2002) reported personal consequences such as feeling bad, low self-esteem, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicide and death in her descriptive study of workplace violent events involving nurses. Physical health effects reported by nurses included both physical and mental exhaustion. One nurse experienced her bodys response to abuse, as breathing heavily, racing heart, excessive perspiration, and her mental state slowing down. Another nurse reported developing a skin ailment; while others reported gastrointestinal complaints, weight-loss, head and backaches, increased blood pressure, and symptoms of depression. One nurse

2010 The Authors. International Nursing Review 2010 International Council of Nurses

Effects of physician-perpetrated abuse

325

observed that in her department, There is an awful lot of sick time for whatever reason and I think part of it is that some nurses cant deal with [the abuse]. The social health of nurses was related to inuences on the desire or ability to function normally outside work. Nurses reported negative effects on themselves, family life, social networks and outside activities. One nurse stated, When youre exhausted and tired, the last thing you want to do is to go home and take care of someone else. Another reported, I have less energy for my home-life. It takes away from the quality time with your spouse. And another, You go home stressed and your husband does something minor and you snap at him or the kids. You cant just turn [the abuse] off like that. One felt that her marriage suffered while she was experiencing ongoing abuse at work. Follingstads (2009) literature review of the impact of psychological aggression on women reported consequences of social isolation and alienation.

Perceived effects on patient care

Nurses reported that because patient conditions can change quickly, continuous constant concentration is required to be an effective patient advocate during the surgical experience. When concentration was disrupted by abuse, nurses reported difculty or inability to concentrate, thereby placing patients in unpredictable situations. One nurse reported, When you are mentally or verbally abused, you get nervous, your attention span is off. You are thinking about what is going on so your patient is most denitely at greater risk. Another stated, That patient was not safe with me for that particular case . . . In a research studying effects of verbal abuse on nurses concentration and productivity, Soeld & Salmond (2003) reported negative effects on nurses abilities to provide patient care. Another nurse recalled an incident when she was scrubbed during a long surgery. She stated that the physician turned from the surgery and began yelling at her. She reported that the physician was not paying attention to the patient while focused on her. Loss of communication between physicians and nurses was reported as a negative effect of abuse during surgery. As one nurse reported, I would withdraw from communication with that physician and avoid eye contact. Another mentioned a physician who refused to speak with her. Whenever there were any matters to do with the OR, like emergency bookings [the physician] would always call day surgery [to book them]. You waste a lot of time getting the information needed to provide the surgery. Buback (2004) also found loss of collaboration among surgical teams was a consequence of verbal abuse in the OR. Difculties with retention and recruitment have potential short- and long-term effects on organizations and may affect patient care as a result of physician-perpetrated abuse. One nurse

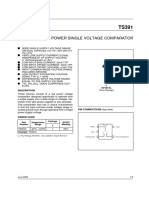

looking elsewhere for work at the time of the interview stated, I worked in the healthcare eld before coming here and felt respected. I have no intention of staying and putting up with these behaviours. OR nursing requires extensive training. Spending the time and effort to train a nurse only to lose them is problematic. One nurse said, . . . orientation, [for a nurse] to be truly skilful, can last well over a year, and if they leave after that it wastes our resources. One nurse stated that she would consider calling in sick if she thought she was going to have to face the same abusive physician two days in a row. Increased absenteeism and sick replacement costs in health care have indirect effects on patients as budgetary dollars are diverted from patient care to replacement costs. Sickness absence affects stafng levels and impacts sick replacement resources. One nurse who left the OR to work elsewhere said, I think in the end they probably lost a really good employee, a real loyal employee. Soeld & Salmond (2003) reported that 13.6% of nurse respondents in a survey involving metropolitan hospitals in northeast USA had left positions because of verbal abuse. A nursing shortage compounded by unsuccessful recruitment has potential to impact surgical procedures in the long term and hence affect patient care (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Nurses shared their perceptions of the effects of abuse on their health and ability to provide patient care. ORs are unique environments that may perpetuate opportunities for abuse because of segregation and lack of the public eye, even though those features are necessary for patient condentiality and safety. Acknowledging the contribution of segregation to the incidence of abuse is a beginning step to addressing it. Increasing presence of authority gures might reduce occurrences of abuse and be viewed as support for physicians and nurses. Addressing the effects of abuse would inuence the health of OR nurses, improve working conditions, increase morale and sustain focus in nursing as a profession. One key nding of this research was that we identied two potential intervention points for addressing abuse. When nurses were new to the OR and when they were in charge of rooms or departments, they were more often at risk of abuse. This nding provides an opportunity to develop interventions specically to address abuse at these points. The data showed that to be effective, intervention strategies need to go beyond blaming the victim and writing policies. When new nurses are overtly criticized for lack of skill and speed, they may inadvertently adopt an overcondent air that increases patient risk. When, however, organizations support the practice of new nurses by consistent mentoring, respectful communication and inclusive orientation programmes, they engage all workers more effectively. Organizational support that extends beyond policy development to

2010 The Authors. International Nursing Review 2010 International Council of Nurses

326

B. L. Higgins & J. MacIntosh

Catalysts for Abuse

Effects on the Nurse

Position & experience of the nurse

Physical health

Emotional health Contextual factors Physicianperpetrated Abuse

Social health

Culture of the Operating Room Effects on the Patient The physical environment Patient safety Hierarchy Access to surgery

Fig. 1 Conceptual framework: culture, catalysts and effects of physician-perpetrated abuse.

afrmative action helps develop a culture of respect for new nurses and for nurse managers. Ensuring that reports of abusive behaviours are addressed by practical organizational consequences is a positive step towards decreasing abuse. Organizations that stand against abuse may nd increased nurse retention and easier recruitment than those with a reputation for ignoring abuse. On an individual level, nurses need to be aware of the impact and consequences of abuse whether they encounter abuse directly or indirectly. Awareness of what is considered abuse and its potential effects will help nurses identify and address it. Nurses who advocate for a respectful workplace and who practice respect can have a positive impact on the environment. Many nurses commented on the need to reduce workplace stress. Most nurses managed stress reduction themselves after work hours through structured exercise classes or informal approaches. Although most health-care facilities provide counselling for employees who request it, use of such services did not appear in these data. Whether and when nurses access such services in relation to workplace abuse might need to be explored. On an organizational level, nurses did not feel well supported by their organizations when they reported abuse. Chevarie (unpublished) noted that social support was vital in nurses work-lives, beneting patients and nurses alike. Organizations that promote effective team communication, facilitate teamwork and conduct inter-disciplinary educational workshops can increase social support among employees. When organizational leaders are increasingly aware of abuse and provide support, they assist managers in addressing abuse. Beyond organizations, the trend toward inter-disciplinary education might prove benecial for all health-care profession-

als. This education might facilitate developing inter-disciplinary respect, emphasize competence in critical thinking, and enable exploring abuse and appropriate responses collaboratively. In addition, such education has the potential to improve effective communication skills (including assertiveness and conict management) and promote reective practice by embedding these skills in inter-disciplinary education. Nurses indicated that experiencing abuse interfered with communication patterns in the OR so this improvement is particularly crucial. Some nurses discussed their concerns about the impact of abuse on sustaining a healthy workforce. They feared that disrespect and abuse would increase recruitment and retention challenges, increase costs of sick time to avoid abuse, and decrease available expertise. Closer examination of these consequences might provide employers with valuable information and lead to examining existing policies that regulate inter-personal behaviour at work.

Conclusion

This research explored OR nurses perceptions of the effects of physician-perpetrated abuse. These negative effects can be used as a starting point to focus closely on workplace dynamics and address detrimental effects that harm both nurses and patients. Although abuse is often a topic of informal conversation amongst nurses, I found little research conducted with OR nurses on this subject. Further study could explore abuse from the perspectives of a range of health-care professionals, hospital units and perpetrators. It would be useful to gain additional insight into the dynamics in the OR that potentially contribute to abusive situations. Research on lost time, illness and employee turnover related to abuse might be of interest to governments

2010 The Authors. International Nursing Review 2010 International Council of Nurses

Effects of physician-perpetrated abuse

327

and policy-makers as they seek solutions for managing nancial constraints and improving patient care.

Strengths and limitations of the research

The goal was to understand and explore nurses perceptions of the effects of physician-perpetrated abuse and its consequences for nurses and patient care. Because participants were not recruited through their workplaces, they may have had a sense of anonymity that allowed them to speak freely, a possible strength of the study. Using the qualitative description method permitted understanding nurses experiences with their own words and depths of emotion. Finding nurses to participate was a slow and challenging process. An initial low return rate from recruitment letters, prompted return to the Research Ethics Board for approval to expand the geographical area and to use the snowball method. These changes assisted in obtaining an adequate number of participants for data saturation. Recruitment may also have been difcult because of the cultural history, the work environment, nurses normalizing the experience, or their perceived lack of time to participate.

Author contributions

B.L Higgins was the principal researcher involved with study conception and data collection. Both authors were involved in the study design, data analysis, drafting of the manuscript and critical revisions for important intellectual content.

References

Alfredsdottir, H. & Bjornsdottir, K. (2008) Nursing and patient safety in the operating room. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 61 (1), 2937. Anderson, C. (2002) Workplace violence: are some nurses more vulnerable? Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 23, 351366. Boyatzis, R.E. (1998) Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. Buback, D. (2004) Assertiveness training to prevent verbal abuse in the OR. AORN Journal, 79 (1), 148164. Bull, R. & FitzGerald, M. (2006) Nursing in a technological environment: nursing care in the operating room. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 12, 37. Chenier, E. (1998) The workplace: a battleground for violence. Public Personnel Management, 27 (4), 557568. Available at: http://proquest.umi.

com/pqdlink?index=1&did=37353982&SrchMode=1&sid=1&Fmt= 6&VInst=PROD&VType=PQD&RQT=309&VName=PQD&TS= 1253110579&clientId=10774 (accessed 25 July 2005). Deans, C. (2004) Nurses and occupational violence: the role of organizational support in moderating professional competence. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 22 (2), 1418. Available at: http:// www.ajan.com.au/Vol22/Vol22.2-2.pdf (accessed 25 July 2005). Di Martino, V. (2000) Violence at the workplace: the global challenge. International Conference on Work Trauma. Available at: http://www.ilo/ .org/public/english/protection/safework/violence/violwk/violwk.htm (accessed 9 February 2006). Di Martino, V. (2002) Workplace Violence in the Health Sector: Country Case Studies Brazil, Bulgaria, Lebanon, Portugal, South Africa, Thailand and an Additional Australian Study. Available at: http://www.ilo.org/ public/english/dialogue/sector/papers/health/violence-ccs.pdf (accessed 6 February 2006). Duncan, S., et al. (2001) Nurses experience of violence in Alberta and British Columbia hospitals. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 32 (4), 5778. Elliot, P. (1997) Violence in health. Nursing Management, 28 (12), 3841. Follingstad, D.R. (2009) The impact of psychological aggression on womens mental health and behaviour: the status of the eld. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 10 (3), 271289. Gerardi, D. (2004) Using mediation techniques to manage conict and create healthy work environments. AACN Clinical Issues: Advanced Practice in Acute and Critical Care, 15 (2), 182195. Henry, J. & Ginn, G. (2002) Violence prevention in healthcare organizations within a total quality management framework. Journal of Nursing Administration, 32 (9), 479486. Kerr, M., et al. (2005) New strategies for monitoring the health of Canadian nurses: results of collaborations with key stakeholders. Nursing Research, 18 (1), 6781. Manderino, M. & Berkey, N. (1997) Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. Journal of Professional Nursing, 13 (1), 4855. Riley, R. & Manias, B. (2005) Rethinking theatre in modern operating rooms. Nursing Inquiry, 12 (1), 29. Rosenstein, A. (2002) Nurse-physician relationships: impact on nurse satisfaction and retention. American Journal of Nursing, 102 (6), 2634. Sandelowski, M. (2000) Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health, 23, 334340. Soeld, L. & Salmond, S. (2003) Workplace violence: a focus on verbal abuse and intent to leave the organization. Orthopaedic Nursing, 22 (4), 274283. Tanner, J. & Timmons, S. (2000) Backstage in the theatre. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34 (4), 975980.

2010 The Authors. International Nursing Review 2010 International Council of Nurses

Copyright of International Nursing Review is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Ab Initio Interview Questions - HTML PDFDocumento131 pagineAb Initio Interview Questions - HTML PDFdigvijay singhNessuna valutazione finora

- Demoversion IWE 2011Documento47 pagineDemoversion IWE 2011Burag HamparyanNessuna valutazione finora

- THE MEDIUM SHAPES THE MESSAGEDocumento56 pagineTHE MEDIUM SHAPES THE MESSAGELudovica MatildeNessuna valutazione finora

- NCP Acute PainDocumento3 pagineNCP Acute PainIsrael Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- Susan Abbotson - Critical Companion To Arthur Miller - A Literary Reference To His Life and Work-Facts On File (2007) PDFDocumento529 pagineSusan Abbotson - Critical Companion To Arthur Miller - A Literary Reference To His Life and Work-Facts On File (2007) PDFTaha Tariq0% (1)

- Monitor Sleep Patterns and InterventionsDocumento1 paginaMonitor Sleep Patterns and InterventionsIsrael Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- Linde E18P-02Documento306 pagineLinde E18P-02ludecar hyster100% (4)

- Impaired Skin IntegrityDocumento7 pagineImpaired Skin Integrityprickybiik100% (8)

- Amoebiasis CaseDocumento51 pagineAmoebiasis CaseChristine Karen Ang SuarezNessuna valutazione finora

- DBM CSC Form No. 1 Position Description Forms 1feb.222019Documento2 pagineDBM CSC Form No. 1 Position Description Forms 1feb.222019Jemazel Ignacio87% (30)

- Drug Study - Paracetamol Ambroxol, Ascorbic Acid, CefuroximeDocumento4 pagineDrug Study - Paracetamol Ambroxol, Ascorbic Acid, Cefuroximeapi-3701489100% (12)

- Nursing Responsibilities For METRONIDAZOLEDocumento1 paginaNursing Responsibilities For METRONIDAZOLEIsrael Soria Espero63% (8)

- Pathophysiology of Peptic Ulcer Disease DefinitionDocumento2 paginePathophysiology of Peptic Ulcer Disease DefinitionIsrael Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- 31660832Documento7 pagine31660832Israel Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- Bullying 1Documento14 pagineBullying 1Israel Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- Main Journal CimpprDocumento13 pagineMain Journal CimpprIsrael Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- AntidoteDocumento1 paginaAntidoteIsrael Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- DR JournalDocumento9 pagineDR JournalIsrael Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- NCP Acute PainDocumento3 pagineNCP Acute Painmanoelsterg50% (2)

- Copd Cad Pathophysiology (Revised)Documento3 pagineCopd Cad Pathophysiology (Revised)Israel Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- 59318928Documento12 pagine59318928Israel Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- 2010 CPRDocumento2 pagine2010 CPRIsrael Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- A Critique On Fad DietsDocumento12 pagineA Critique On Fad DietsIsrael Soria EsperoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ts 391 IltDocumento5 pagineTs 391 IltFunnypoumNessuna valutazione finora

- Timesheet 2021Documento1 paginaTimesheet 20212ys2njx57vNessuna valutazione finora

- CV of Prof. D.C. PanigrahiDocumento21 pagineCV of Prof. D.C. PanigrahiAbhishek MauryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Infineon ICE3BXX65J DS v02 - 09 en PDFDocumento28 pagineInfineon ICE3BXX65J DS v02 - 09 en PDFcadizmabNessuna valutazione finora

- R20qs0004eu0210 Synergy Ae Cloud2Documento38 pagineR20qs0004eu0210 Synergy Ae Cloud2Слава ЗавьяловNessuna valutazione finora

- Chrysler Corporation: Service Manual Supplement 1998 Grand CherokeeDocumento4 pagineChrysler Corporation: Service Manual Supplement 1998 Grand CherokeeDalton WiseNessuna valutazione finora

- 2019-03-30 New Scientist PDFDocumento60 pagine2019-03-30 New Scientist PDFthoma leongNessuna valutazione finora

- Spec 2 - Activity 08Documento6 pagineSpec 2 - Activity 08AlvinTRectoNessuna valutazione finora

- Quiz - DBA and Tcont Bw-TypesDocumento4 pagineQuiz - DBA and Tcont Bw-TypesSaifullah Malik100% (1)

- Superelement Modeling-Based Dynamic Analysis of Vehicle Body StructuresDocumento7 pagineSuperelement Modeling-Based Dynamic Analysis of Vehicle Body StructuresDavid C HouserNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Google Like A Pro-10 Tips For More Effective GooglingDocumento10 pagineHow To Google Like A Pro-10 Tips For More Effective GooglingMinh Dang HoangNessuna valutazione finora

- Term Paper Mec 208Documento20 pagineTerm Paper Mec 208lksingh1987Nessuna valutazione finora

- Capital Asset Pricing ModelDocumento11 pagineCapital Asset Pricing ModelrichaNessuna valutazione finora

- SQL DBA Mod 1 IntroDocumento27 pagineSQL DBA Mod 1 IntroDivyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Expert Java Developer with 10+ years experienceDocumento3 pagineExpert Java Developer with 10+ years experienceHaythem MzoughiNessuna valutazione finora

- ENY1-03-0203-M UserDocumento101 pagineENY1-03-0203-M UserAnil KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- AGCC Response of Performance Completed Projects Letter of recommendAGCC SS PDFDocumento54 pagineAGCC Response of Performance Completed Projects Letter of recommendAGCC SS PDFAnonymous rIKejWPuS100% (1)

- Chapter 6 Performance Review and Appraisal - ReproDocumento22 pagineChapter 6 Performance Review and Appraisal - ReproPrecious SanchezNessuna valutazione finora

- Dragonshard PC GBDocumento42 pagineDragonshard PC GBWilliam ProveauxNessuna valutazione finora

- E85001-0646 - Intelligent Smoke DetectorDocumento4 pagineE85001-0646 - Intelligent Smoke Detectorsamiao90Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sahrudaya Health Care Private Limited: Pay Slip For The Month of May-2022Documento1 paginaSahrudaya Health Care Private Limited: Pay Slip For The Month of May-2022Rohit raagNessuna valutazione finora

- Grid Xtreme VR Data Sheet enDocumento3 pagineGrid Xtreme VR Data Sheet enlong bạchNessuna valutazione finora

- Day / Month / Year: Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Applicant Data Collection Form (LOCAL)Documento4 pagineDay / Month / Year: Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Applicant Data Collection Form (LOCAL)Lhea RecenteNessuna valutazione finora

- 1Z0-062 Exam Dumps With PDF and VCE Download (1-30)Documento6 pagine1Z0-062 Exam Dumps With PDF and VCE Download (1-30)Humberto Cordova GallegosNessuna valutazione finora