Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Reconciling The Patent Exhaustion and Conditional Sale Doctrines in Light of Quanta Computer v. LG Electronics Erin Julia Daida Austin

Caricato da

R Hayim BakaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Reconciling The Patent Exhaustion and Conditional Sale Doctrines in Light of Quanta Computer v. LG Electronics Erin Julia Daida Austin

Caricato da

R Hayim BakaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

RECONCILING THE PATENT EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE DOCTRINES IN LIGHT OF QUANTA COMPUTER V.

LG ELECTRONICS

Erin Julia Daida Austin*

INTRODUCTION Imagine that Seller owns a valid patent for technology incorporated into a machine that produces widgets. Buyer purchases the widget machine from Seller. As a condition of the purchase, Buyer promises to restrict his use of the machine in some respect. For example, Buyer may promise eventually to return the used machine only to Seller and not to any third-party refurbisher or reseller.1 Or Buyer may promise to use the machine to produce no more than one thousand widgets, after which point Buyer promises to dispose of the machine.2 Perhaps Buyer promises to use the machine only to produce widgets for personal use and not for commercial use.3 If Buyer violates such a promise, should Seller have a cause of action against Buyer for breach of contract, for patent infringement, or for both? Significant debate exists about whether or to what degree patentees4 should be able to enforce post-sale restrictions5 against

* J.D. Candidate (June 2010). I would like to thank my husband and daughter, Joel and Sophie, for their encouragement and support. Thank you also to Professor Alan Wolf, Victoria Elman, and Etan Chatlynne for their advice and comments on this Note. 1 This restriction is inspired by Ariz. Cartridge Remfrs. Assn v. Lexmark Intl Inc., 421 F.3d 981 (9th Cir. 2005). 2 The restriction on the number of widgets produced is inspired by Mallinckrodt v. Medipart, 976 F.2d 700 (Fed. Cir. 1992). 3 The restriction on the type of use is inspired by Gen. Talking Pictures Corp. v. W. Elec. Co., 304 U.S. 175 (1938). 4 A patentee is the owner of the monopoly rights under an issued patent. See infra note 10. An assignee of rights under the patent stands in the same shoes. E.g., DONALD S. CHISUM, CHISUM ON PATENTS 22.01 (Patents are subject to general legal rules on the ownership and transfer of property. The patent statutes provide that a patent shall have the attributes of personal property. They also provide that both patents and patent applications shall be assignable in law by an instrument in writing. (citing 35 U.S.C. 261)). 5 A patentee might desire to restrict the purchasers right to remake or repair, use, or resell the patented article. Principally at issue in this Note are limitations on the purchasers right to use the patented article.

2947

2948

CARDOZO LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 30:6

purchasers,6 as in the Seller-Buyer example presented, through a suit for patent infringement.7 Specifically, some see a conflict between the patent exhaustion doctrine, long established by the Supreme Court,8 and the conditional sale doctrine as recently implemented by the Federal Circuit.9 While a patent gives the owner the right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the patented invention within the United States,10 this right is limited by the exhaustion doctrine (also called the first sale doctrine), which holds that the first authorized sale11 of a patented article removes that article from the patent monopoly such that any subsequent use is not infringement.12 If patent rights have been exhausted by an authorized sale, post-sale restrictions can only be enforced, if at all, under a contract theory.13 But the Federal Circuit has held that a conditional sale, in which the patentee restricts the right of

6 A purchaser may buy a patented article directly from the patentee or assignee, or from an intermediate manufacturer licensed to make and sell the patented article. Additionally, the purchaser may be the end user of the patented good, or the purchaser may incorporate the patented article into another article that he then sells. If it should have legal significance whether the purchaser, e.g., buys directly from the patentee versus from an intermediate licensee, this Note so indicates. 7 See, e.g., Mark R. Patterson, Contractual Expansion of the Scope of Patent Infringement Through Field-of-Use Licensing, 49 WM. & MARY L. REV. 157 (2007); William P. Skladony, Quanta Computer v. LG Electronics: The US Supreme Court May Consider the Doctrine of Patent Exhaustion, 19 NO. 7 INTELL. PROP. & TECH. L.J. 1 (2007); Richard H Stern, The Unobserved Demise of the Exhaustion Doctrine in US Patent Law: Mallinckrodt v. Medipart, 15 EUR. INTELL. PROP. REV. 460 (1993). 8 See JAY DRATLER, JR., LICENSING OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY 7.05 (noting that the patent exhaustion doctrine is judicially created while the copyright exhaustion doctrine is statutory). 9 See, e.g., Skladony, supra note 7, at 1 (A tension has developed between these lines of cases, and it is focused for Supreme Court consideration.); Stern, supra note 7, at 461 (stating that the Mallinckrodt decision recognizing a conditional sale swept away a century or more of exhaustion doctrine). 10 35 U.S.C. 281 (2006) (giving a patentee remedy by civil action for infringement of his patent); 35 U.S.C. 271(a) (2006) ([W]hoever without authority makes, uses, offers to sell, or sells any patented invention, within the United States or imports into the United States any patented invention during the term of the patent therefore, infringes the patent.). 11 A sale is the transfer of a piece of property or the title for a price. BLACKS LAW DICTIONARY 631 (3d Pocket ed. 2006). Contrastingly, a license is the transfer of rights in property without transferring the ownership of the property. Dratler, Jr., supra note 8, at 1.01. 12 E.g., Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Elecs., Inc., 128 S. Ct. 2109, 2115 (2008) ([T]he initial authorized sale of a patented item terminates all patent rights to that item.); U.S. v. Univis Lens Co., 316 U.S. 241, 250 (1942); Adams v. Burke, 84 U.S. (17 Wall.) 453, 455-56 (1873); Bloomer v. McQuewan, 55 U.S. 539, 549-50 (1852). In the Seller-Buyer widget machine example, finding that Sellers patent rights were exhausted would mean that Seller could not sue Buyer for patent infringement based on the manner in which Buyer used the machine. 13 55 U.S. at 549-50 ([H]e must seek redress in the courts of the State, according to the laws of the State and not in the courts of the United States, nor under the law of Congress granting the patent); O.W. HOLMES, JR., THE COMMON LAW 301 (1881) (The only universal consequence of a legally binding promise is, that the law makes the promisor pay damages if the promised event does not come to pass.). In the Seller-Buyer widget machine example, Seller could sue Buyer for breach of contract, but not for patent infringement, based on Buyers use of the machine in violation of his promise.

2009]

EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE

2949

the purchaser to use the patented article through an enforceable contract, can prevent exhaustion and preserve the patentees right to sue for infringement if the condition is not met or the restriction is violated.14 Thus, in the example above, the exhaustion doctrine would limit Seller to a suit for breach of contract while the conditional sale doctrine would allow Seller to sue Buyer for patent infringement and breach of contract. Whether patent rights may be preserved by a conditional sale is important because of several significant differences between a cause of action for patent infringement and a cause of action for breach of contract. First, activity that is found to be within the scope of a valid patent grant is subject to lower antitrust scrutiny than activity that is not conducted under the auspice of a patent.15 Second, whereas damages for breach of contract are generally compensatory,16 patentees may

14 E.g., B. Braun Med., Inc. v. Abbott Labs., 124 F.3d 1419, 1426 (Fed. Cir. 1997); Mallinckrodt v. Medipart, 976 F.2d 700, 709 (Fed. Cir. 1992); PATENTS AND THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT 14.3 (8th ed., BNA, 2007) ([The] exhaustion doctrine, however, does not apply to an expressly conditional sale or license.). For example, in the Seller-Buyer widget machine hypothetical, finding that the sale of the machine was conditioned on Buyers use of the machine and that Buyers use violated the condition would mean that Seller could sue Buyer for patent infringement. 15 Patterson, supra note 7, at 165 (noting that contractual restrictions do not receive any of the protection from antitrust scrutiny that might be accorded a restriction under patent law); DONALD S. CHISUM, CHISUM ON PATENTS: A TREATISE ON THE LAW OF PATENTABILITY, VALIDITY, AND INFRINGEMENT 19.04(2) (2008) (Both the misuse doctrine and the antitrust laws as applied to patent practices involve a common inquiry: Should the practice in question be treated as an appropriate exercise of the patentees statutory patent rights? If the answer to the inquiry is affirmative, then the practice is not an improper extension within the meaning of the patent misuse doctrine and should enjoy an immunity from antitrust liability even though but for the patent the practice would violate the antitrust laws.). But see Atari Games Corp. v. Nintendo of Am., Inc., 897 F.2d 1572, 1576-77 (Fed. Cir. 1990) (The fact that a patent is obtained does not wholly insulate the patent owner from the antitrust laws. When a patent owner uses his patent rights not only as a shield to protect his invention, but as a sword to eviscerate competition unfairly, that owner may be found to have abused the grant and may become liable for antitrust violations when sufficient power in the relevant market is present. (internal citations omitted)). 16 UCC 1-106 (The remedies provided by this Act shall be liberally administered to the end that the aggrieved party may be put in as good a position as if the other party had fully performed but neither consequential or special nor penal damages may be had . . . .) (2007); ARTHUR LINTON CORBIN, CORBIN ON CONTRACTS 55.3 (2008) (In determining the amount of this compensation as the damages to be awarded, the aim in view is to put the injured party in as good a position as that party would have been in if performance had been rendered as promised. . . . As a corollary to this proposition it is a basic tenet of contract law that the aggrieved party will not be placed in a better position than it would have occupied had the contract been fully performed.); Id. at 59.2 (Although such awards are increasingly important in tort litigation, punitive damages are usually not awarded in contract actions, no matter how egregious the breach. It is often said that the rules as to damages for breach of contract are applied for the purpose of giving compensation for injury done, and not for punishment of a wrongdoer.); E. ALLEN FARNSWORTH, FARNSWORTH ON CONTRACTS 12.8, at 189-90 (1990) (Furthermore, no matter how reprehensible the breach, damages that are punitive, in the sense of being in excess of those required to compensate the injured party for the lost expectation, are not ordinarily awarded for breach of contract.). But see id. at 191-96 (detailing the increasing frequency with which courts grant punitive damages in breach of contract cases).

2950

CARDOZO LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 30:6

recover treble damages17 and attorneys fees18 for successful claims of willful patent infringement.19 Third, patentees may obtain injunctions to enjoin infringing activity for the remainder of the patent term,20 while

17 35 U.S.C. 284 (2006) ([T]he court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed.). A finding of willful infringement is a sufficient basis for increased damages. See, e.g., Johns Hopkins Univ. v. CellPro, Inc., 152 F.3d 1342, 1364 (Fed. Cir. 1998) ([I]t is well established that enhancement of damages may be premised upon a finding of willful infringement.); Beatrice Foods Co. v. New England Printing and Lithographing Co., 923 F.2d 1576, 1578 (Fed. Cir. 1991) ([I]t is well-settled that enhancement of damages must be premised on willful infringement or bad faith. (quoting Yarway Corp. v. Eur-Control USA, Inc., 775 F.2d 268, 277 (Fed. Cir. 1985))). However, a finding of willful infringement does not require an award of treble damages. Modine Mfg. Co. v. Allen Group, Inc., 917 F.2d 538, 543 (Fed. Cir. 1990) ([A] finding of willful infringement merely authorizes, but does not mandate, an award of increased damages.) (emphasis in original); Robert W. Morris, Note, Another Pound of Flesh: Is There a Conflict Between the Patent Exhaustion Doctrine and Licensing Agreements?, 47 RUTGERS L. REV. 1557, 1571 (2007) (The goal of monetary relief is to restore the patent owner to the financial position he would have enjoyed had the infringement not occurred.). 18 35 U.S.C. 285 (2006) allows the court to award the prevailing party attorneys fees in an exceptional case. Modine, 917 F.2d at 543 (An express finding of willful infringement is a sufficient basis for classifying a case as exceptional, and indeed, when a trial court denies attorney fees in spite of a finding of willful infringement, the court must explain why the case is not exceptional within the meaning of the statute.). 19 See Kimberly A. Moore, Empirical Statistics on Willful Patent Infringement, 14 FED. CIR. B.J. 227 (2004). Moore analyzed 1721 patent infringement cases for which litigation terminated from 1999-2000 and found that willful infringement was alleged in 92.3% of complaints. Id. at 232. Of 143 studied cases that went to trial, willfulness was found 55.7% of the time, and enhanced damages were awarded in 55.7% of cases where willfulness was found. Id. at 237. In other words, enhanced damages were awarded in 31.0% of the 143 tried cases. 20 35 U.S.C. 283 (2006) (The several courts having jurisdiction of cases under this title may grant injunctions in accordance with the principles of equity to prevent the violation of any right secured by patent, on such terms as the court deems reasonable.). A recent Supreme Court opinion rejected a general rule that injunctions should be the remedy for patent infringement. eBay, Inc. v. MercExhange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388 (2006). Granting a permanent injunction for the patentee, the Federal Circuit stated that courts will issue permanent injunctions against patent infringement absent exceptional circumstances. MercExchange, LLC v. eBay, Inc., 401 F.3d 1323, 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2005), revd 547 U.S. 388. The Supreme Court reversed, holding that injunctions should issue under the Patent Act according to the traditional four-factor test employed by courts of equity requiring the plaintiff to demonstrate: (1) that it has suffered an irreparable injury; (2) that remedies available at law, such as monetary damages, are inadequate to compensate for that injury; (3) that, considering the balance of hardships between the plaintiff and defendant, a remedy in equity is warranted; and (4) that the public interest would not be disserved by a permanent injunction. 547 U.S. at 391-92. Nonetheless, injunctions are still often found to be an appropriate remedy in infringement suits: From at least the early 19th century, courts have granted injunctive relief upon a finding of infringement in the vast majority of patent cases. This long tradition of equity practice is not surprising, given the difficulty of protecting a right to exclude through monetary remedies that allow an infringer to use an invention against the patentees wishes-a difficulty that often implicates the first two factors of the traditional four-factor test. This historical practice, as the Court holds, does not entitle a patentee to a permanent injunction or justify a general rule that such injunctions should issue. . . . At the same time, there is a difference between exercising equitable discretion pursuant to the established four-factor test and writing on an entirely clean slate. . . . . in this area as others, a page of history is worth a volume of logic.

2009]

EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE

2951

injunctions are less frequently granted in contract cases.21 Fourth, while a claim for breach of contract can only be brought against one with whom the complainant has privity of contract22 or a third-party beneficiary relationship,23 a patent infringement suit requires no special relationship between the patentee and the alleged infringer.24 A fifth consideration is that the Federal Circuit has exclusive25 jurisdiction over appeals related to patent cases,26 whereas breach of contract is generally a state law issue.27 Patentees may prefer the Federal Circuit since it is

547 U.S. at 395 (Roberts, C.J., concurring) (internal citations omitted, emphasis in original); Benjamin Petersen, Note, Injunctive Relief in the Post-eBay World, 23 BERKELEY TECH. L.J. 193, 217 (2008) (Although injunctive relief is no longer nearly automatic, post-eBay district court decisions do not suggest that injunctions are now rare. Indeed, the effect of eBay seems limited almost exclusively to non-practicing patent holders who are not in direct competition with the infringer.). 21 HOLMES, supra note 13; 25 WILLISTON ON CONTRACTS 67:8 (4th ed.) ([A]s a general rule, before specific performance may be decreed for breach of a contract . . . the remedy at law, that is, damages, must first have been determined to be incomplete and inadequate to accomplish substantial justice.). 22 For an example of the formalistic view requiring privity, see Lawrence v. Fox, 20 N.Y. 268, 275 (1859) (Comstock, J. dissenting) (In general, there must be privity of contract. The party who sues upon a promise must be the promisee, or he must have some legal interest in the undertaking.). See also Brief of American Intellectual Property Law Association as Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent at 32, Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Elec.s, Inc., 128 S. Ct. 2109 (2008) (No. 06-937) [hereinafter Brief of AIPLA] ([C]ontract remedies are not helpful since they are often inadequate to accomplish the objectives because they require privity . . . .); Kieff, infra note 168, at 326 (Even an innocent infringer, without knowledge of a patent, who makes something covered by a valid patent claim with her own hands from materials gathered from land she and her ancestors have owned free and clear since time immemorial, is nonetheless liable for patent infringement.). 23 Lawrence, 20 N.Y. at 271 ([W]here one person makes a promise to another for the benefit of a third person, that third person may maintain an action upon it.). 24 Cf. ProCD, Inc. v. Zeidenberg, 86 F.3d 1447, 1454 (1996) (A copyright is a right against the world. Contracts, by contrast, generally affect only their parties; strangers may do as they please, so contracts do not create exclusive rights.). To illustrate, a patentee and alleged infringer need not have bargained for a promise by the alleged infringer that he would not infringe; rather, the patentee has a right to proceed against anyone who makes, uses, or sells her patented article in the United States without her authorization. Many of the cases discussed in this Note involve contracts between the relevant parties, or arrangements that might be classified as third-party beneficiary relationships. However, this Note suggests that whether a patentee can enforce her property rights under the patent law should not turn on whether she has privity with the infringer. 25 To be precise, the Federal Circuit has nearly exclusive jurisdiction over appeals in patent cases. The Federal Circuit does not have exclusive appellate jurisdiction where patent claims arise only in counterclaims and not in the complaint. Holmes Group, Inc. v. Vornado Air Circulation Sys., Inc., 535 U.S. 826 (2002). 26 28 U.S.C. 1295(a)(1) (2006); Atari, Inc. v. J.S. & A Group, Inc., 747 F.2d 1422 (Fed. Cir. 1984), overruled on other grounds by Nobelpharma Ab. v. Implant Innovations, 141 F.3d 1059 (Fed. Cir. 1998) ([T]his courts jurisdiction to hear appeals from district court judgments is unique and depends, by statutory direction, on whether the district courts jurisdiction was based, in whole or in part, on [a patent claim under] Section 1338.). 27 Power Lift, Inc. v. Weatherford Nipple-Up Systems, Inc., 871 F.2d 1082, 1085 (Fed. Cir. 1989) (A [patent] license agreement is a contract governed by ordinary principles of state contract law.); Aronson v. Quick Point Pencil Co., 440 U.S. 257, 262 (1979) (Commercial agreements traditionally are the domain of state law. State law is not displaced merely because

2952

CARDOZO LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 30:6

perceived as being pro-patentee.28 Because of these differences, patentees may desire to retain patent rights, as opposed to mere contractual rights, by including restrictions in sales or licensing agreements.29 In Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc.,30 the Supreme Court addressed the rights of patentee LG Electronics (LGE) with respect to a purchaser from LGEs licensed manufacturer. LGE licensed intermediate manufacturer Intel to make, use, and sell computer components that practiced LGEs patents.31 The language of the LGE-Intel licensing agreement purportedly reserved LGEs patent rights against Intels purchasers.32 Purchaser Quanta bought components from licensee Intel and assembled them into computers that practiced LGEs patents.33 When Quanta and Intels other purchasers refused to pay LGE licensing fees, LGE sued the purchasers for patent infringement.34

the contract relates to intellectual property . . . .). 28 For a list of several articles asserting this view, see Kimberly A. Moore, Markman Eight Years Later: Is Claim Construction More Predictable?, 9 LEWIS & CLARK L. REV. 231, 240 n.32 (2005). But see id. at 241 (noting that, at least with regard to claim construction, the Federal Circuit finds in favor of accused infringers more often than not, belying the claim the that court is pro-patentee). 29 Norman E. Rosen, Intellectual Property and the Antitrust Pendulum: Recent Developments at the Interface Between the Antitrust and Intellectual Property Laws, 62 ANTITRUST L.J. 669, 687 (1994) (stating that damages for patent infringement would generally exceed breach of contract damages); Elizabeth I. Winston, Why Sell What You Can License? Contracting Around Statutory Protection of Intellectual Property, 14 GEO. MASON L. REV. 93, 108 (2006) ([P]atent infringement . . . is likely to be a more lucrative action than breach of contract for violating a license restriction.). Of course, the two branches of law are not mutually exclusive. It is probably most desirable to have protection under both the patent law and private contract provisions. 30 128 S. Ct. 2109 (2008). 31 To practice a patent means to make and use the patented invention. For example, this could mean constructing and operating a patented machine or carrying out a patented process. 32 128 S. Ct. at 2114. Thus, LGE could sue Intels purchasers for patent infringement, but Intel would not be contributorily liable even though it had sold components designed to practice LGEs patents. Opinions differ as to whether this aspect of the LGE-Intel agreement was poor drafting, an attempt to trap Intels purchasers, or savvy strategy based on the state of the law at the time. Compare F. Scott Kieff, Quanta v. LG Electronics: Frustrating Patent Deals by Taking Contracting Options off the Table?, 2008 CATO SUP. CT. REV. 315, 315-16 (stating that one interpretation of the Quanta opinion is that the LGE-Intel contract was poorly written, but suggesting the real reason the Supreme Court heard the case was to comment on the types of patent licensing agreements that it approves) with Harold C. Wegner, Post-Quanta, Post-Sale Patentee Controls, 7 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 682, 683 (calling LGEs licensing strategy ingenious) and id. at 690 (describing LGEs licensing strategy as taking full advantage of the Federal Circuit case law). Without speculating on LGEs intent, the author of this Note acknowledges that the particular language of these agreements creates some uncertainty as to how to interpret the reach of the Quanta opinion. 33 128 S. Ct. at 2113 (In this case, we decide whether patent exhaustion applies to the sale of components of a patented system that must be combined with additional components in order to practice the patented methods.). 34 Complaint for Patent Infringement, LG Elecs. Inc. v. Q-Lity Computer Inc., No. C0120319, 2001 WL 36117917 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 16, 2001).

2009]

EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE

2953

The Court held that, under the exhaustion doctrine, Intels authorized sale of components that sufficiently embodie[d] LGEs patents terminated LGEs patent rights.35 The Court found that the LGE-Intel licensing agreement triggered exhaustion because it gave Intel unconditional authority to sell components that had no reasonable use other than practicing the LGE patents.36 The Quanta opinion did not explicitly address the broader question of whether patent owners can ever avoid exhaustion through a conditional sale. It is debatable whether the Courts finding regarding the lack of conditionality in the LGE-Intel licensing agreement was based on the specific language of the documents at issue, or whether it was a more general pronouncement against attempts by patentees to reserve rights against purchasers.37 In the wake of the Quanta decision, some commentators doubt the viability of the conditional sale doctrine as articulated by the Federal Circuit over the past two decades.38 They have suggested that the Courts conclusion regarding the LGE-Intel agreement implies that a

35 128 S. Ct. at 2122 (Because Intel was authorized to sell its products to Quanta, the doctrine of patent exhaustion prevents LGE from further asserting its patent rights with respect to the patents substantially embodied by those products.). The Courts opinion drew heavily from United States v. Univis Lens Co., 316 U.S. 241 (1942), in which the sufficient embodiment test for exhaustion was first developed. See infra Part I.A. See also infra note 126 for a discussion of when an article sufficiently embodies a patent. 36 Id. at 2122 (No conditions limited Intels authority to sell products substantially embodying the patents.). This is the second prong of the exhaustion test set forth in Univis. See infra Part I.A. 37 See supra note 32 and accompanying text. 38 For commentary arguing that Quanta overrules the conditional sale doctrine articulated in Mallinckrodt, see, e.g., Chris Holman, Quanta and Its Impact on Biotechnology, Holmans Biotech IP Blog (June 11, 2008), http://holmansbiotechipblog.blogspot.com/2008/06/quanta-andits-impact-on-biotechnology.html (opining that Quanta implicitly overrules Mallinckrodt); Wegner, supra note 32, at 682, 691 (stating that Quanta sub silentio overrules Federal Circuit precedent holding that exhaustion does not apply to expressly conditional sales or licenses). For commentary asserting that Quanta leaves the conditional sale doctrine intact, see, e.g., Dratler, Jr., supra note 12, at 7.05 (stating that the Quanta opinion leaves open the question of the extent to which parties may limit the effect of the exhaustion doctrine through the language of their licensing agreement and that whether Mallinckrodt survives is an open question); David McGowan, Reading Quanta Narrowly, Patently-O (July 27, 2008), http://www.patentlyo.com/patent/2008/07/reading-quanta.html (arguing that Quanta did not address conditional licenses or pass-through conditions and therefore does not undercut Mallinckrodt); Shubha Ghosh, The Quandry of Quanta: Thoughts on the Supreme Court Decision One Week Later, Antitrust & Competition Policy Blog (June 17, 2008), http://lawprofessors.typepad.com/antitrustprof_blog/2008/06/the-quandry-of.html (discussing whether Quanta undercuts Mallinckrodt or whether the cases can be read as consistent with each other); Robert W. Gomulkeiwicz, The Federal Circuits Licensing Law Jurisprudence: Its Nature and Influence, WASH L. REV. (forthcoming 2009), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1281045, 42-43 (stating that Quanta actually affirms the Mallinckrodt line of cases on the conditional sale doctrine); Steven Z. Szczepanski, Updated by David M. Epstein, 2 ECKSTROMS LICENSING IN FOREIGN & DOMESTIC OPERATIONS 8:22 (Thomson Reuters West 2008) (calling Quanta an affirmation of the conditional sale doctrine).

2954

CARDOZO LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 30:6

patentee can never avoid exhaustion via a conditional sale.39 On the other hand, the Quanta opinion can be read more narrowly as only holding that the LGE-Intel agreement before the Court was not a conditional sale,40 while reserving the decision as to whether patent rights may be preserved by other types of agreements.41 Part I of this Note begins by tracing the evolution of the exhaustion and conditional sale doctrines through the case law. Part I also describes the Quanta litigation and the Supreme Courts treatment of the case. Part II disputes the contention that there is a conflict between the exhaustion and conditional sale doctrines. It describes how the two doctrines may be read as consistent with each other and why preserving the conditional sale doctrine is desirable. Part III proposes an exhaustion analysis that incorporates principles from both Quanta and Mallinckrodt v. Medipart, the leading Federal Circuit case on the conditional sale doctrine. It also makes some observations and suggestions about structuring patent licensing agreements after Quanta. I. HISTORY OF THE EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE DOCTRINES A. The Supreme Courts Exhaustion Doctrine

A patentee may bring an infringement suit42 to prevent another43 from making, using, selling, or offering to sell a patented invention,44 and can recover damages for infringing activities.45 In response, the alleged infringer may, inter alia, defend her actions based on the theory that an earlier authorized sale of the patented article, whether by the patentee or her authorized licensee, terminated all patent rights with respect to that item.46 The exhaustion doctrine first arose in a series of nineteenth-century patent infringement cases addressed by the Supreme Court. In Bloomer v. McQuewan,47 the assignee48 of patent rights to make and sell the

See, e.g., Holman, supra note 38. See infra Parts I.C.ii and III.B. E.g., McGowan, supra note 38. 35 U.S.C. 281 (2006). 35 U.S.C. 283 (2006). 35 U.S.C. 271(a) (2006). 35 U.S.C. 284 (2006). E.g., U.S. v. Univis Lens Co., 316 U.S. 241 (1942); Adams v. Burke, 84 U.S. (17 Wall.) 453 (1873); Bloomer v. McQuewan, 55 U.S. (14 How.) 539 (1852); CHISUM, supra note 15, at 16.03(2)(a). 47 55 U.S. 539 (1852). 48 At the time, assignment was governed by R.S. 4898. See Keeler v. Standard Folding Bed Co., 157 U.S. 659, 661 (1894) ( [E]very patent or any interest therein shall be assignable in law by an instrument in writing, and the patentee and his assigns or legal representatives may in like

39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46

2009]

EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE

2955

Woodworth planing machine49 during an extension of the patent term50 sued a prior purchaser from the patentee for infringement.51 The assignee claimed that the purchaser infringed on his exclusive right by using the two previously purchased machines during the extended term.52 The Court held that the first sale by the patentee removed the purchasers machines from the patent monopoly53 and therefore exhausted the right of the patentee, or his assignee, to sue for infringement.54 Shortly thereafter, in Adams v. Burke,55 the Supreme Court explained that the exhaustion doctrine is premised on the idea that the patentee receives just compensation for disclosure of his invention from the first authorized sale.56 Adams and Keeler v. Standard Folding

manner grant and convey an exclusive right under his patent to the whole or any specified part of the United States.). It was often the case that the patentee divided the territory of the United States into twenty or more specified parts through assignments. Id. at 662; see also CHISUM, supra note 15 at 19.04(3)(h) (It is generally assumed that a patent owner may assign or license the right to practice the invention on a territorially restricted basis.). 49 A planing machine is a machine for smoothing or shaping wood. WEBSTERS THIRD NEW INTERNATIONAL DICTIONARY 1730-31 (Philip Babcock Gove, Ph.D., ed., G. & C. Merriam Co., 1976) (1961). 50 The Patent Act of 1836 allowed a patentee to obtain a seven-year extension of the original fourteen-year patent term upon a showing that such an extension was necessary for the patentee to obtain reasonable remuneration for his investment in the invention. Patent Act of 1836, ch. 306, 18, 5 Stat. 117, 124-25. Such renewal extended to assignees and grantees of the patent. Bloomer, 55 U.S. at 549. In 1861, Congress abolished the extension system and adopted a uniform seventeen-year patent term. Act of March 2, 1861, ch. 137, 16, 12 Stat. 246, 249; C. Michael White, Why a Seventeen Year Patent?, 38 J. PAT. OFF. SOCY 839 (1956). In 1994, Congress enacted the current twenty-years-from-filing patent term. 35 U.S.C. 154(a)(2) (2006); H.R. REP. NO. 103-826(I), at 8 (1994), reprinted in 1994 U.S.C.C.A.N. 3773. 51 55 U.S. at 548. Purchaser McQuewan bought from the patentee Woodworth the right to make and use two patented wood planing machines within the Pittsburgh area. Id. Subsequently, assignee Bloomer obtained the exclusive right to construct and use the patented machine in the greater Pittsburgh area during an extension of the patent term. Id. 52 Id. 53 Id. at 549 ([W]hen the machine passes to the hands of the purchaser, it is no longer within the limits of the monopoly. It passes outside of it, and is no longer under the protection of the act of Congress.). 54 Id. at 549-50. The court distinguished between a licensee of the rights to manufacture and sell the patented invention, who buys with respect to the patent term, and a purchaser of the right to use the machine. Id. at 549 ( But the purchaser of the implement or machine for the purpose of using it in the ordinary pursuits of life, stands on different ground.). 55 84 U.S. (17 Wall.) 453 (1873). Lockhart & Steelye obtained the right to make and sell patented coffin lids within a ten-mile radius of Boston (the Boston circle), while Adams obtained a similar right to make and sell the coffin lids outside the Boston circle. 84 U.S. at 454. Burke, an undertaker, purchased a coffin-lid from Lockhart & Steelye within the Boston circle, but then used it to bury a body within Adams territory. Id. The Court found that Adams (an assignee) could not maintain an infringement suit against Burke (a purchaser) because Burkes purchase from authorized sellers in Boston exhausted all patent rights with respect to the coffin lid in any territory. Id. at 456-57. 56 Id. at 456 ([W]hen the patentee, or the person having his rights, sells a machine or instrument whose sole value is in its use, he receives the consideration for its use and he parts with the right to restrict that use.); see also Bloomer v. Millinger, 68 U.S. 340, 350 (1863) ([Patentees] are entitled to but one royalty for a patented machine, and consequently when a patentee has himself constructed the machine and sold it, or authorized another to construct and

2956

CARDOZO LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 30:6

Bed57 also illustrated that a purchaser obtained the right to use58 and to resell59 the patented invention free and clear of geographic restrictions limiting the rights of the assignee seller. Construing the Sherman Antitrust Act and Clayton Act in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,60 the Court also defined some limits on the types of restricted sales and tiered licensing agreements

sell it, or to construct and use and operate it, and the consideration has been paid to him for the right, he has then to that extent parted with his monopoly, and ceased to have any interest whatever in the machine so sold or so authorized to be constructed and operated.); William P. Skladony, Commentary on Select Patent Exhaustion Principles in Light of the LG Electronics Case, 47 IDEA 235, 238 (2007) ([W]ith respect to the conveyance of an article, the patent exhaustion doctrine is based on a fundamental notion that the patent owner gets only one bite at the apple.). Other rationales for the exhaustion doctrine include (1) the historical dislike of restraints on alienation or servitudes on personal property, (2) an ownership interest rationale, (3) concerns about anticompetitive effects, and (4) enforcing the scope of the statutory patent grant. See Brief of Various Law Professors as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondent at 3, Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Elec.s, Inc., 128 S.Ct. 2109 (2008) (No. 06-937) [hereinafter Brief of Various Law Professors] (noting the laws skepticism towards restrictive servitudes as well as the general understanding that no servitudes run with the sale of ordinary chattels); id. at 14-15 & n.4; Michael A. Carrier, Cabining Intellectual Property Through a Property Paradigm, 54 DUKE L.J. 1, 115 (2004) (analogizing the patent exhaustion doctrine to the common law prohibition of restraints on alienation); William A. Birdwell, Exhaustion of Rights and Patent Licensing Market Restrictions, 60 J. PAT. OFF. SOCY 203, 212-13, 216 (1978) (stating that the best rationale for the exhaustion doctrine is that since the exclusive patent right is a limited exception to the national competition policy . . . the exercise of this right should be cut off after the first sale of the patented goods because the sale provides adequate financial reward to stimulate invention . . . .); John W. Osborne, Justice Breyers Bicycle and the Ignored Elephant of Patent Exhaustion: An Avoidable Collision in Quanta v. LGE, 7 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 245, 293 (2008) [hereinafter Justice Breyers Bicycle] (noting that patent exhaustion is reflective of the scope of patent rights granted by statute). 57 157 U.S. 659 (1895). The inventor of an improvement in wardrobe bedsteads assigned his patent rights to various parties in different geographic regions. Id. at 659. Keeler & Bros. purchased wardrobes from the Michigan assignee and resold the wardrobes in Massachusetts. Id. The Supreme Court held that the Massachusetts assignee could not sue purchaser Keeler for patent infringement because patent rights were exhausted by the authorized sale from the Michigan assignee. Id. at 662 ([T]he purchaser of a patented machine has not only the right to continue the use of the machine so long as it exists, but to sell such machine, and that his vendee takes the right to use.). The court reasoned, [W]hen the royalty has once been paid to a party entitled to receive it, the patented article then becomes the absolute, unrestricted property of the purchaser, with the right to sell it as an essential incident of such ownership. Id. at 664. The Court left open the possibility that the patentee might protect himself and his assignees by contracting directly with the purchaser. Id. at 666 (Whether a patentee may protect himself and his assignees by special contracts brought home to the purchasers is not a question before us, and upon which we express no opinion.). 58 E.g., Bloomer v. McQuewan, 55 U.S. 539 (1853); Adams v. Burke, 84 U.S. 453 (1873). 59 Keeler, 157 U.S. at 661 ([I]t is obvious that a purchaser can use the article in any part of the United States, and, unless restrained by contract with the patentee, can sell or dispose of the same.). 60 For a brief history of the relationship between antitrust and intellectual property laws, see Herbert Hovenkamp, Innovation and the Domain of Competition Policy, 60 ALA. L. REV. 103, 108-14 (2008). For a thorough treatment of the antitrust-intellectual property relationship, see HERBERT HOVENKAMP, IP AND ANTITRUST: AN ANALYSIS OF ANTITRUST PRINCIPLES APPLIED TO INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW (2002).

2009]

EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE

2957

patentees could enforce.61 At issue in Bauer & Cie v. ODonnell62 was whether a patentee could enforce vertical price restraints,63 which it included in a licensing contract and on a label license,64 via a patent infringement suit against a purchaser from its licensee. The patentee argued that its patent rights survived the authorized sale from a licensed refinery to a jobber65 because the products label stated a minimum resale price.66 The Court found that the sale from the licensee to the jobber exhausted the patentees rights67 and that the patent statute did not authorize the patentee to set the price of transactions beyond the initial authorized sale.68 Subsequently, the Court relied on the patent exhaustion doctrine to

61 After the passage of the Sherman Act in 1890, several antitrust cases involving the sale of patented articles presented opportunities for the Supreme Court to revisit the patent exhaustion doctrine. See William A. Birdwell, Exhaustion of Rights and Patent Licensing Market Restrictions, 60 J. PAT. OFF. SOCY 203, 203 (1978) (In addition to barring a patent infringement action to prevent the purchaser of patented goods from using or disposing of those goods as he chooses, this principle [the exhaustion doctrine] has been applied also to find contractual restraints on the use or disposition of such goods by their purchaser illegal under antitrust law.). Prior to these cases, the Supreme Court had declined to decide whether a patentee could place express restrictions or conditions on the sale of patented goods, saying that the patentee could exert any desired control through licenses or assignments to manufacturers. Morris, supra note 17 at 1579 n.115; Hobbie v. Jennison, 149 U.S. 355, 363 (1893) (It is easy for a patentee to protect himself and his assignees . . . . He can take care to bind every licensee or assignee, if he gives him the right to sell articles made under the patent, by imposing conditions which will prevent any other licensee or assignee from being interfered with.). 62 229 U.S. 1 (1913). 63 A vertical price restraint is price-fixing among parties in the same chain of distribution, such as manufacturers and retailers, attempting to control an items resale price. BLACKS LAW DICTIONARY 853 (8th ed. 2004). At the time of the Bauer decision, vertical price restraints were considered per se illegal. Bauer & Cie, 229 U.S. at 11-12 (citing Dr. Miles Med. Co. v. John D. Park & Sons Co., 220 U.S. 373 (1911), overruled by Leegin Creative Leather Prods. v. PSKS, Inc., 127 S. Ct. 270 (2007)). 64 A label license is a notice on an items package granting the purchaser a license to practice the process by using the item without additional payments to the licensor. BLACKS LAW DICTIONARY 939 (8th ed. 2004). 65 A jobber is one who buys from a manufacturer and sells to a retailer; a wholesaler or middleman. BLACKS LAW DICTIONARY 853 (8th ed. 2004). 66 The products label included a Notice to Retailer stating that the retail price was to be no less than one dollar, that anyone who sold the product for less than that amount would be liable to an injunction and damages (the typical remedies for patent infringement), and that purchase of the item was acceptance of these conditions. 229 U.S. at 8-9. The object of the notice is said to be to effectually maintain prices and to prevent ruinous competition by the cutting of prices in sales of the patented article. Id. at 11. Retailer ODonnell sold the article for less than the one-dollar minimum price set by the patentee, so the Bauer Chemical Company refused to supply him with additional product. Id. at 9. When ODonnell subsequently purchased the article from a jobber and resold it for less than one dollar, patentees Bauer & Cie sued him for patent infringement. 67 Id. at 17. 68 Id. (The right to vend conferred by the patent law has been exercised, and the added restriction is beyond the protection and purpose of the act.). The Court reasoned by analogizing to the exhaustion doctrine in copyright law. See Bobbs-Merrill v. Straus, 210 U.S. 339 (1908) (holding that the first authorized sale of a copyrighted work exhausted rights under the copyright statute). For an overview of the exhaustion doctrine in copyright law, see MELVILLE B. NIMMER, NIMMER ON COPYRIGHT 8.12 (Matthew Bender 2008).

2958

CARDOZO LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 30:6

conclude that patentees could not tie69 the sale of unpatented articles to the use of patented ones.70 For example, the Court held that the patent laws did not permit a patentee to require purchasers of its patented movie projectors also to purchase its unpatented films or risk infringement for using the projector with another manufacturers film.71 The Court also applied the exhaustion doctrine, along with the Sherman Antitrust Act, to strike down an anticompetitive tiered licensing arrangement for the sale of a patented gasoline.72 The patentee attempted to control the parties to and prices of all sales of gasoline containing its patented additive.73 The Court held that the patentees rights were exhausted by its first sale of the gasoline to the licensed refiners.74 In its most recent opinion on patent exhaustion prior to Quanta, the Supreme Court set forth a two-prong test for patent exhaustion. At issue in United States v. Univis Lens Co.75 was whether the authorized

69 See BLACKS LAW DICTIONARY 1557 (8th ed. 2004) (defining a tying arrangement as [a] sellers agreement to sell one product or service only if the buyer also buys a different product or service . . . . Tying arrangements may be illegal under the Sherman or Clayton Act if their effect is too anticompetitive.). 70 Motion Picture Patents Co. v. Universal Film Mfg. Co., 243 U.S. 502 (1917). Motion Picture Patents (MPP) owned patent rights directed toward a film-feeding mechanism used in motion picture projectors. Id. at 505. MPP required its manufacturing licensee Precision Machine Company to sell the projectors with an attached plaque that stated the projector could only be used with film that was also licensed by MPP. Id. at 506-07. MPP brought a patent infringement suit against a purchaser of one of the projectors, and against rival film-maker Universal, after its patent directed toward the film technology had expired. Id. at 507-08. 71 The Supreme Court held that, since MPP had market power with respect to the projectors, such a tying restriction was illegal. Id. at 508 (finding market power): Such a restriction is invalid because such a film is obviously not any part of the invention of the patent in suit; because it is an attempt, without statutory warrant, to continue the patent monopoly in this particular character of film after it has expired, and because to enforce it would be to create a monopoly in the manufacture and use of moving picture films, wholly outside of the patent in suit and of the patent law as we have interpreted it. Id. at 518. 72 Ethyl Gasoline Corp. v. United States, 309 U.S. 436 (1940). Ethyl Corporation owned patents directed toward the use of a gasoline additive. Id. at 446. The patentee derived its profits from the sale of the patented fluid to licensed oil refiners, but also instituted a licensing scheme to control the subsequent sale of the gasoline from the refiners to jobbers. Id. at 446, 450-52. In an antitrust suit brought by the government, the Court found that this licensing arrangement was an impermissible attempt to enlarge Ethyls monopoly and struck it down under the Sherman Act. Id. at 456-58. 73 Id. at 457-59. 74 The Court reasoned that Ethyls sale of the patented fuel to refiners exhausted its patent rights, and therefore Ethyl could not control the refiners sale of the fuel to jobbers under either patent or contract law. Id. at 457-59. 75 316 U.S. 241 (1942). Univis owned several patents directed toward the shape, size, and composition of pieces of glass of different refractive power fused together to create multifocal ophthalmic lenses. Id. at 246-47. The patentee instituted a tiered licensing scheme in which it granted licenses to wholesalers, finishing retailers, and prescription retailers that set forth from whom the licensees could buy unfinished lens blanks, to whom the licensees could sell the lenses they finished, and at what prices each licensee was to sell its products. Id. at 244-45. Univis

2009]

EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE

2959

sale of unpatented lens blanks76 could exhaust the patentees rights with the regard to the patented finished lenses that were produced from the blanks. The Court held that the sale of the blanks triggered exhaustion.77 This decision expanded the scope of the exhaustion doctrine by holding that the authorized sale of unpatented articles78 could exhaust patent rights if the articles sold (1) embodied the essential features of the patents, and (2) had no utility other than to practice the patents.79 Thus, the exhaustion doctrine terminates the right of a patentee to sue a purchaser for infringement when that purchaser has already paid a fair price to use, repair, and resell the article. Application of the doctrine requires a determination of whether there has been an unconditional and authorized sale of an article embodying the essential inventive features of the patent. Where such sale has occurred, the article has been removed from the patent monopoly and cannot be the subject of an infringement suit. B. The Federal Circuits Conditional Sale Doctrine

The conditional sale doctrine developed simultaneously with the exhaustion doctrine, albeit with less guidance from the Supreme Court. While an authorized and unconditional sale exhausts the patentees

argued its patent monopoly was a defense to the governments antitrust claims. Id. at 243. 76 The lens blanks at issue were rough opaque pieces of glass of suitable size, design and composition for use, when ground and polished, as multifocal lenses in eyeglasses. Id. at 244. 77 Id. at 249-50. Sale of a lens blank by the patentee or by his licensee is thus in itself both a complete transfer of ownership of the blank, which is within the protection of the patent law, and a license to practice the final stage of the patent procedure. In the present case the entire consideration and compensation for both is the purchase price paid by the finishing licensee to the Lens Company. 78 Licensed wholesalers sold unfinished lens blanks to licensed retailers, who then finished the lenses and sold the finished products at prices fixed by Univis. Id. at 244. The Court stipulated that Univiss patents were not fully practiced until the blanks were finished, but nonetheless held that Univis could not set prices for the sales by retailers. Id. at 248. 79 [E]ach blank embodies essential features of the patented device and is without utility until it is ground and polished as the finished lens of the patent. Id. at 249. We think that all the considerations which support these results lead to the conclusion that where one has sold an uncompleted article which, because it embodies essential features of his patented invention, is within the protection of his patent, and has destined the article to be finished by the purchaser in conformity to the patent, he has sold his invention so far as it is or may be embodied in that particular article. The reward he was demanded and received is for the article and the invention which it embodies and which his vendee is to practice upon it. Id. at 250-51. See Wegner, supra note 38, at 685 (describing the Univis decision as plugging a loophole that would have allowed patentees to circumvent the exhaustion doctrine by selling unpatented goods to a purchaser who then finished them into the patented article).

2960

CARDOZO LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 30:6

property rights,80 an unauthorized sale or conditional sale does not bar the patentee from reserving patent rights. The concepts of a conditional patent license and sale can be traced at least back to Mitchell v. Hawley,81 in which the Supreme Court, in 1873, recognized that a patent owner might grant a manufacturer a license to make and vend a patented invention limited to a fixed span of time.82 In that case, a licensee was granted manufacturing rights limited to the original patent term and expressly excluding any extension of the term.83 The Court held that a subsequent assignee during the extended term could bring an infringement suit against a purchaser from the licensee during the original term.84 The case illustrates that a patentee, or his assignee, can enforce restrictions on a purchasers post-sale use of a patented article through an infringement suit. The Supreme Court approved of field-of-use restrictions, which limit use of a patented invention to a specified application or market,85 in General Talking Pictures Corp. v. Western Electric Co.,86 where it held that patent owners could grant restricted licenses to manufacturers87 and enforce the restrictions against the licensees purchasers through infringement suits. Similar to its reasoning in

Supra Part I.A. 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 544 (1873). Patentee Taylor granted Bayley a license to make, use, and license to others his patented felting machine in New England during, but explicitly not beyond, the original patent term. Bayley sold four of the machines to Hawley with notice of Taylors patent. Id. at 549-50. Subsequently, the patentee assigned his rights under an extended term to Mitchell, who sued Hawley for infringement based on his continued use of the machines during the extended term. Id. at 549. The Court held that assignee Mitchell could enjoin purchaser Hawley from using the four patented machines during the extended term. Id. at 549. The facts of Mitchell contrast those of Bloomer, supra Part I.A. and notes 47-53, in a manner that illustrates the relationship between exhaustion and conditional licenses. In Bloomer, the unconditioned license gave rise to exhaustion; in Mitchell, the conditioned license prevented exhaustion. 83 See supra text accompanying note 48. 84 The Court reasoned that licensee Bayley never had the authority to sell the right to use the patented machines indefinitely, and that [n]o one in general can sell personal property or convey a valid title to it unless he is the owner or lawfully represents the owner. Id. at 550. 85 See generally CHISUM, supra note 15, at 19.04(3)(a); R. CARL MOY, MOYS WALKER ON PATENTS at 18:34 (4th ed. 2008). 86 304 U.S. 175, rehg granted, 304 U.S. 587 (1938). American Telegraph & Telephone Co. (AT&T) owned several patents directed toward vacuum tube amplifiers that were used in different technological areas including telephony and motion picture projection. Id. at 176, 179. AT&T reserved for its subsidiary the exclusive right to make and sell the amplifiers in the commercial field (i.e. for use in movie theater equipment). Id. at 179. AT&T granted American Transformer Company (ATC) a license to make and sell amplifiers for private use only. Id. at 180-81. General Talking Pictures (GTP) purchased amplifiers from ATC and leased them to movie theaters in knowing violation of the restriction in the AT&T-ATC license. Id. at 180. AT&Ts subsidiary, Western Electric, sued ATC and GTP for patent infringement, to which GTP raised a defense of exhaustion via the ATC-GTP sale. Id. at 179-80. 87 Id. at 181 (Unquestionably, the owner of a patent may grant licenses to manufacture, use or sell upon conditions not inconsistent with the scope of the monopoly. . . . Patent owners may grant licenses extending to all uses or limited to use in a defined field.).

80 81 82

2009]

EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE

2961

Mitchell v. Hawley, the Court stated that the licensees purchaser could not obtain a right that the licensee was not authorized to sell.88 On rehearing,89 the court emphasized that restrictive patent licenses were historically recognized90 and legal.91 In Mallinckrodt v. Medipart,92 the Federal Circuit93 set forth its interpretation of the conditional sale doctrine. At issue was whether patentee Mallinckrodt could enforce single-use-only restrictions on the use of its patented nebulizers via infringement suits against parties that reconditioned and reused the nebulizers.94 The Federal Circuit held that, if the single-use restriction was a valid condition under sales law95 and within the scope of Mallinckrodts patent grant,96 Mallinckrodt could bring a claim of patent infringement against parties that violated the restriction.97 The court reasoned that, since a patentee has a complete right to exclude others from use under the patent grant,98 the patentee may choose to waive only a portion of that exclusive right.99

88 Id. (The Transformer Company could not convey to petitioner what both knew it was not authorized to sell. (citing Mitchell v. Hawley, 16 Wall. at 550)). 89 Gen. Talking Pictures Corp. v. W. Elec. Co., 305 U.S. 124, 127 (1938). 90 Id. at 127 (noting that [t]he practice of granting licenses for a restricted use is an old one). 91 Id. (That a restrictive license is legal seems clear. (citing Mitchell v. Hawley, 16 Wall. 544)). 92 976 F.2d 700 (Fed. Cir. 1992). 93 The Federal Circuit was established as an Article III court in 1982. See generally http://www.cafc.uscourts.gov/about.html. The Federal Circuit has nearly exclusive appellate jurisdiction over cases involving questions of patent law. 28 U.S.C. 1295; supra note 25. 94 Mallinckrodt owned patents directed toward the nebulizer and manifold components of a medical device used to administer radioactive or therapeutic compounds in an aerosol mist to the lungs of patients suffering from various lung diseases. Mallinckrodt, 976 F.2d at 701; Mallinckrodt, Inc. v. Medipart, Inc., 1990 WL 19535, *1, n.1 (N.D. Ill. 1990). The device was sold to hospitals bearing the inscription Single Use Only. Mallinckrodt, 976 F.2d at 702. However, some hospitals shipped used devices to Medipart, which would have the devices cleaned, repackaged, and sold back to the hospitals for subsequent use. Id. Mallinckrodt sued Medipart for patent infringement and inducement to infringe. Id. 95 The Federal Circuit did not pass on the question of whether the single-use-only label license was an enforceable contract condition. Id. at 701. Nor did the district court have the opportunity to decide this issue on remand because the parties settled. Stern, supra note 7, at 461. However, the Federal Circuit opinion did acknowledge that contractual conditions must not violate the antitrust or patent misuse laws. 976 F.2d at 708. 96 Id. (i.e., that it relates to subject matter within the scope of the patent claims). But see DRATLER, JR., supra note 8, at 7.05 (criticizing the Federal Circuits reliance on the scope of the patent analysis in Mallinckrodt as outmoded and dismissive of significant antitrust concerns). 97 Mallinckrodt, 976 F.2d at 709. 98 35 U.S.C. 154 (2006). 99 This right to exclude may be waived in whole or in part. 976 F.2d at 703. The rule is, with few exceptions, that any conditions which are not in their very nature illegal with regard to this kind of property, imposed by the patentee and agreed to by the licensee for the right to manufacture or use or sell the [patented] article, will be upheld by the courts. Id. (citing E. Bement & Sons v. National Harrow Co., 186 U.S. 70, 91 (1902)).

2962

CARDOZO LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 30:6

Subsequent Federal Circuit and district court decisions have relied on Mallinckrodt for the proposition that restricted licenses and conditional sales prevent the exhaustion of patent rights.100 In B. Braun Medical, Inc. v. Abbott Laboratories,101 the Federal Circuit explained that exhaustion does not apply to an expressly conditional sale or license because it is reasonable to infer that the parties negotiated a price that only reflected the value of the limited use rights conferred by the patentee.102 The Federal Circuits frequent reliance on its relatively recent Mallinckrodt opinion has prompted some to predict a collision between this line of Federal Circuit cases and older Supreme Court exhaustion precedent. C. 1. Quanta v. LG Electronics

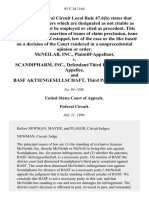

Background and Proceedings Below

The tension between the exhaustion and conditional sale doctrines appeared to come to a head in the Quanta litigation.103 LGE owned a

100 E.g., Monsanto Co. v. McFarling, 302 F.3d 1291, 1293 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (upholding a preliminary injunction in favor of patentee Monsanto where Monsanto alleged that a purchasers use of second-generation genetically modified soybean seeds, in violation of a signed Technology Agreement prohibiting the purchaser from saving and using any subsequent-generation seeds, violated Monsantos patent directed toward the genetically modified seeds); Monsanto Co. v. Scruggs, 459 F.3d 1328, 1335-36 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (upholding a preliminary injunction in favor of patentee Monsanto against a purchaser who allegedly infringed Monsantos patent for genetically-modified soybean seeds by saving, replanting, and selling second-generation seeds); Ariz. Cartridge Remfrs. Assn v. Lexmark Intl, Inc., 290 F. Supp. 2d 1034, 1045 (N.D. Cal. 2003) (finding that patent exhaustion would not apply where patentee Lexmark validly conditioned the sale of its patented printer ink cartridges on the purchasers implicit agreement to return the used cartridges only to Lexmark), affd Ariz. Cartridge Remfrs. Assn, Inc. v. Lexmark Intl Inc., 421 F.3d 981 (9th Cir. 2005) (based on a finding that Lexmark had a facially valid contract with its purchasers under Californias adoption of UCC 2-204). Compare Lexmark to Hewlett-Packard Co. v. Repeat-O-Type Stencil Mfg. Corp., 123 F.3d 1445 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (holding that it was not infringement for a company to refill patented printer cartridges because the exhaustion doctrine applied). 101 124 F.3d 1419 (Fed. Cir. 1997). 102 Id. at 1426. Patentee Braun sold Abbot its patented reflux valves on the condition that Abbot would only incorporate the valves into specific articles that did not compete with Brauns own product lines. Id. at 1422. Abbot then bought allegedly infringing valves from another manufacturer and incorporated them into products that were prohibited under the Braun-Abbot sales agreement. Id. When Braun sued Abbot for infringement, Abbot argued that placing postsale field-of-use restrictions on patented articles constituted patent misuse. Id. The Federal Circuit disagreed; it held that Braun could sue for patent infringement if the lower court found that the use restriction was within the scope of Brauns patent grant and passed the rule of reason test. Id. at 1426-27. 103 See LG Elecs., Inc. v. Asustek Computer Inc., 2002 WL 31996860 at *2, 65 U.S.P.Q.2d 1589 (N.D. Cal. 2002) [hereinafter Asustek I], modified by LG Elecs., Inc. v. Asustek Computer, Inc., 248 F. Supp. 2d 912 (N.D. Cal. 2003) [hereinafter Asustek II], reversed in part by LG Elecs., Inc. v. Bizcom Elecs., Inc., 453 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2006), reversed by Quanta Computer,

2009]

EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE

2963

portfolio of patents directed toward computer components.104 In 2000, LGE entered into a broad cross-licensing agreement105 with Intel,106 pursuant to which Intel paid LGE a sum of money and agreed to provide discounts on future purchases107 in exchange for the right to make, use,

Inc. v. LG Elecs., Inc., 128 S. Ct. 2109 (2008). 104 At issue in Quanta were three patents owned by LG Electronics directed toward computer components and processes. See LG Elecs., 453 F.3d at 1368. Representative claims are as follows: A data processing system including one or more central processing units, main memory means, and bus means . . . and means for detecting whether data corresponding to the address of said transferred data unit and determined to be stored in said cache memory means may be different in content from said transferred data unit and, if so, transmitting said data from said cache memory means to said bus means for reception by the bus connection requesting the data unit [i.e., ensuring the most current data is retrieved from memory]. U.S. Patent No. 4,939,641 (filed June 30, 1998). A memory control unit for controlling a main system memory of a data processing system, the main system memory being comprised of at least one memory unit . . . for comparing a received read address to write addresses stored in said write address buffer means . . . . [i.e., coordinating requests to read and write from main memory]. U.S. Patent No. 5,379,379 (filed Sept. 6, 1990). A method for determining priority of access to a bus among a set of devices coupled to the bus . . . the method comprising the steps of: receiving an access request in a node from a represented device; determining whether any node with a higher priority has received an access request; if no such node has received an access request, permitting the device to access the bus; counting a number of accesses by the device to the bus; and in response to predetermined number of accesses to the bus, giving another node the highest priority. U.S. Patent No. 5,077,733 (filed Sept. 11, 1989). Microprocessors carry out the main functions of computer systems by interpreting program instructions, processing data, and controlling other devices. 128 S. Ct. at 2113. A microprocessor is connected to the other devices via a set of wires called a bus and a chipset. Id. The components disclosed in the LGE patents had to be combined with standard parts in order to create a functioning computer. Id. at 2119. 105 A patent license is a waiver of liability for infringement and may provide immunity against claims of contributory infringement. See W. Elec. Co. v. Pacent Reproducer Corp., 42 F.2d 116, 117 (2d Cir. 1930), cert. denied 282 U.S. 873 (1930) (In its simplest form, a license means only leave to do a thing which the licensor would otherwise have a right to prevent. Such a license grants to the licensee merely a privilege that protects him from a claim of infringement by the owner of the patent monopoly.); De Forest Radio Tel. & Tel. Co. v. United States, 273 U.S. 236, 242 (1927) (As a license passes no interest in the monopoly, it has been described as a mere waiver of the right to sue by the patentee.); ROGER M. MILGRIM & ERIC E. BENSEN, 2 MILGRIM ON LICENSING 15.47 (describing a license as an assurance of immunity from suit). Crosslicensing agreements are prevalent in the semiconductor industry. See, e.g., Mehdi Ansari, LG Electronics, Inc. v. Bizcom Electronics, Inc.: Solving the Foundry Problem in the Semiconductor Industry, 22 BERKELEY TECH. L.J. 137, 138 (2007) (stating that leading semiconductor manufacturers have used broad cross-licensing agreements to provide patent peace and allow[] development of parallel technology); Dan Callaway, Note, Patent Incentives in the Semiconductor Industry, 4 HASTINGS BUS. L.J. 135, 137 (2008) ([L]arge semiconductor companies encourage their rivals to enter cross-licensing agreements.); Morris, supra note 17, at 1560 (stating that broad cross-licensing agreements were commonly used by semiconductor manufacturers to increase their freedom of design in the early days of the industry). 106 See Morris, supra note 17, at 1589 (describing Intels strategy of accumulating patents and entering broad cross-licensing agreements to achieve patent peace). 107 Asustek I at *2.

2964

CARDOZO LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 30:6

sell (directly or indirectly), offer to sell, import or otherwise dispose of its own products that practiced the LGE patents.108 Thus, Intel could manufacture and sell the systems claimed in the LGE patents and devices designed to practice LGEs method claims without liability for infringement. The licensing agreement stated that no license was granted by LGE to any third party that purchased components from Intel.109 A separate master agreement between LGE and Intel required Intel to notify its customers, which it did, that while Intel had obtained a broad license from LGE, such license would not extend to any product made by combining an Intel product with a non-Intel product.110 The master agreement specified that failure to give the required notice would not terminate Intels license.111 Quanta purchased microprocessors and chipsets from licensee Intel that were designed to practice the LGE patents.112 Quanta combined these components with standard, non-Intel components to make computers that practiced the LGE patents.113 Patentee LGE sued Quanta for patent infringement based on this allegedly unauthorized

Asustek I at *4; Quanta Computer, 128 S. Ct. at 2114. No license is granted by either party hereto . . . to any third party for the combination by a third part of Licensed Products of either party with items, components, or the like acquired . . . from sources other than a party hereto, or for the use, import, offer for sale or sale of such combination. 128 S. Ct. at 2114. One author has suggested this language was employed to avoid the foundry problem, in which a chip foundry with a broad cross-license (e.g., Intel) is employed by the licensors competitors to make infringing products that the competitor takes free and clear of the patentees rights. Ansari, supra note 105, at 151-52; see also Kieff, infra note 154, at 320 (arguing that Intel intended to purchase patent peace, or freedom to operate, only for itself and leave its purchasers to deal with patentee LGE as they saw fit); supra note 32 (for additional interpretations of the LGE-Intel contracting language). The licensing agreement also stated that it did not alter the rules of patent exhaustion. 128 S. Ct. at 2114 (Notwithstanding anything to the contrary contained in this Agreement, the parties agree that nothing herein shall in any way limit or alter the effect of patent exhaustion that would otherwise apply when a party hereto sells any of its Licensed Products.). See Brief of Various Law Professors at 6 (stating that, in Mitchell v. Hawley, the Supreme Court treated the first sale doctrine is a default rule that parties could opt out of contractually); Kief, infra note 154, at 322 (describing exhaustion as a default rule that parties can contract around). 110 Brief for LG at *9. It was stipulated that Quanta received this notice. Asustek II at 914 (Defendants were informed of this limitation in the LGE-Intel License when, several days prior to entering into the LGE-Intel License, Intel sent a letter to all its customers . . . .). See Justice Breyers Bicycle, supra note 56, at 274 (interestingly characterizing this arrangement as classic tying). 111 128 S. Ct. at 2114 ([A] breach of this Agreement shall have no effect on and shall not be grounds for termination of the Patent License. (citing Brief for Petitioners at 9)). Other authors have noted that the facts of this case complicate the issue of patent exhaustion. David L. McCombs, et al., Intellectual Property Law, 61 SMU L. REV. 907, 917 (2008). See also supra note 36 and accompanying text. 112 128 S. Ct. at 2114. The purchased components could not practice LGEs patents until combined with other standard components. Id. at 2118. 113 Id. at 2114.

108 109

2009]

EXHAUSTION AND CONDITIONAL SALE

2965

combination.114 The district courts first opinion held that the LGE-Intel licensing agreement was an exhaustion-triggering unconditional first sale115 and therefore granted summary judgment to the defendant purchasers, including Quanta.116 Upon motion for reconsideration, the district court reversed itself with regard to exhaustion of LGEs method claims.117 The district court maintained that Intels sales were unconditional,118 but followed Federal Circuit precedent in holding that method claims could

114 LGE originally sued multiple defendants for infringement of at least seven patents. See, e.g., LG Elecs., Inc. v. Q-Lity Computer, Inc., WL 36117917 (complaint). Only three patents were at issue in the appeal that reached the Supreme Court. 128 S. Ct. at 2113. The defendants premised their theories of non-infringement on the patent exhaustion and implied license doctrines. Implied license is an equitable doctrine that prevents a patentee from maintaining an infringement claim when the patentees own conduct implied a license to practice the patented invention. See Asustek I at *3; see also LG Elecs., Inc. v. Bizcom Elecs., Inc., 453 F.3d 1364, 1369 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (stating there is implied license where the circumstances of the sale . . . plainly indicate that the grant of a license should be inferred) (internal quotations and citations omitted). This theory was considered by the District Court, but was not critical to its first decision in favor of the defendant purchasers. Asustek I at *14 (holding that the Court need not determine whether the implied license doctrine also applies to the sale of Intel microprocessors and chipsets). With regard to exhaustion, LGE argued that Intels sale of the microprocessors could not have exhausted its patent rights because its claims were to systems that required combination of the microprocessors with additional components in order to practice the patented methods; thus, Intel had not sold the patented articles. Asustek I at *4; see also LG Elecs., 453 F.3d at 1368 (LGE brought suit against defendants, asserting that the combination of microprocessors or chipsets with other computer components infringes LGEs patents covering those combinations. LGE did not assert patent rights in the microprocessors or chipsets themselves.) (emphasis original). 115

Therefore, because LGE licensed to Intel the right to practice LGEs patents and sell products embodying its patentsand Intels production and sale of its microprocessors and chipsets are covered by this agreementLGE forfeited its potential infringement claims against those who legitimately purchase and use the Intel microprocessor and chipset. Asustek I at *4. 116 Asustek I at *14. In finding that the unpatented components sold by Intel exhausted LGEs patents, the district court employed the essential embodiment/no reasonable non-infringing use test from Univis. Asustek I at *11 ([T]he patent exhaustion doctrine also applies to the sale of non-patented devices which have no use other than as components in a device that practices the patent.). 117 35 U.S.C. 101 sets forth four categories of patentable inventions: process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter. Claims to processes are also called method claims. See generally Chisum, supra note 15, at 1.03 regarding method claims. 118 Austek II at 917 (Defendants purchase of the microprocessors and chipsets from Intel was unconditional, in that Defendants purchase of microprocessors and chipsets was in no way conditioned on their agreement not to combine the Intel microprocessors and chipsets with other non-Intel parts and then sell the resultant products.). The district court found that the letter from Intel was not sufficient to demonstrate that its purchasers agreed to LGEs conditions. Id. Note that Asustek II focuses on the unconditional nature of the Intel-Quanta transaction whereas the opinion in Asustek I described the operative unconditional sale as that between LGE and Intel. The Supreme Courts opinion confirms that the Asustek II analysis is correct and the exhausting transaction was the Intel-Quanta sale.

2966

CARDOZO LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 30:6

not be exhausted by the sale of an article.119 The Federal Circuit reversed on the question of whether there was a conditional sale. Citing a Uniform Commercial Code provision governing additional terms in contracts between merchants,120 the panel found that Intels notice conditioned the Intel-Quanta sale and therefore preserved LGEs patent rights against Quanta.121 2. The Supreme Court Reverses on Conditionality and Exhaustion

The unanimous Supreme Court opinion addressed whether the exhaustion doctrine applied to the sale of unpatented components122 that must be combined with other components to practice patented methods.123 Finding that the components sold by Intel essentially embodied the inventive aspects of the LGE patents124 and had no reasonable use other than to practice the LGE patents,125 the Court held that the sale from Intel to Quanta exhausted LGEs patent rights.126