Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Queez in Art Hock Et

Caricato da

bigbigbig90003270Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Queez in Art Hock Et

Caricato da

bigbigbig90003270Copyright:

Formati disponibili

INFORMATION TO USERS

This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films

the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and

dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be trom any type of

computer printer.

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the

copy submitted. Broken or indistind print, colored or paor quality illustrations

and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper

alignment can adversely affect reproduction.

ln the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript

and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized

copyright materia1had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.

Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by

sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing

from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.

Photographs incJuded in the original manuscript have been reproduced

xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6- x 9- black and white

photographie prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing

in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order.

Bell & Howell Information and Leaming

300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 USA

800-521-0600

NOTE TO USERS

This reproduction is the best copy available.

Queezinart-hocket in a blenJu

for chamber ensemble

Athesis submitted to the

Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research

in partial fulfillment of the requirements ofthe degree of

Master of Music in Composition

Andriy Talpash

McGill University, Montral

March 1999

1+1

National Library

of Canada

Acquisitions and

Bibliographie Services

395 Wellington Street

Ottawa ON K1A ON4

Canada

Bibliothque nationale

du Canada

Acquisitions et

services bibliographiques

395, rue Wellington

Ottawa ON K1 A ON4

Canada

Your file Vorre re'erflflt:6

Our file Norre referencB

The author has granted a non-

exclusive licence allowing the

National Library of Canada ta

reproduce, loan, distribute or sell

copies of this thesis in microfonn,

paper or electronic fonnats.

The author retains ownership of the

copyright in this thesis. Neither the

thesis nor substantial extracts from it

may be printed or otherwise

reproduced without the author' s

penmSSlon.

L'auteur a accord une licence non

exclusive pennettant la

Bibliothque nationale du Canada de

reproduire, prter, distribuer ou

vendre des copies de cette thse sous

la fonne de microfiche/film, de

reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat

lectronique.

L'auteur conserve la proprit du

droit d'auteur qui protge cette thse.

Ni la thse ni des extraits substantiels

de celle-ci ne doivent tre imprims

ou autrement reproduits sans son

autorisation.

0-612-55123-7

Canada

Abstract

Queezinart - hocket in a blender is a composition for five woodwinds, five

brass, percussion (two players), piano, two violins, viola, cello and double bass,

with a duration of approximately 14 minutes. There are six main sections in this

piece. The work is structured 50 that musical ideas flow smoothly and gradually

between sections. Also, the musical events are organized in such a way that the

perceived, experienced tinte is manipulated and distorted, through varying

activity and density of musical events.

Acknowledgments

1 would like to express my appreciation to the following: Prof. Brian

Chemey for his knowledge and valuabIe guidance; Prof. Denys BouBane for

taking the tinte to leam and conduct this work; members of the McGill

Contemporary Music Ensemble for the preparation and performance of the

work; Scott Godin for bis advice and being himself; my family for lifelong

support; and my wife Lesia for her endless love and inspiration.

ii

Contents

Abstract

Acknowledgments ii

Qlleezinart - hocket in ablender 1

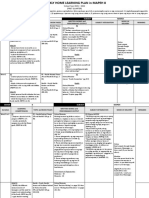

Analysis

Introduction 50

Manipulation of time 51

Sectional analysis

Section A 55

Section B 58

Section C 60

Section D 61

Sections E & F 64-

Relationships within global form 67

Bibliography 68

iii

Queeziuart-Ilocket ill a blender

Instrumentation.:

Oule

oboe. doubling on 2 crystal glasses (tuned ta A4 and Bb4)

clarinet in Bn..t

basa clarinet in 8 fIat, doubling on c1arinet in B flat

bassoon. doubling on 2 crystal glasses (tuned ta D5 .nd ES)

hominF

trumpet in Bnat

trombone

bus trombone

tuba

percussion 1:

glockenspiel. marimba. bi.ngle. suspended cymbal. 4 sm.U Chinese gong

cymbals, 2 bongos, 4 low t a m ~ t o m s . bass drum

percussion 2:

crotales. vibraphone (matar ofO. 2 wood blk.5. 4 cowbells, olutomobile

brake drum. bell tree. suspended cymb.tl. large tam-tam. timpani (tuned

ta El. Bb2. D3. AJ)

piatna

2violins

viola

violoncelle

double b.tss (wtth a lew C e:\teruian)

This 5 .. transposed score.

Ouralion: approxim.ately 14'.

J:bO

\\ Q\J

ee1

i.l\a,t ... in a.

JO

FI.Jte,

j

Il

Oboe,

l

"n

C.lui.,.,t

C1tt; ntt

no

r-- 1

i"

1

\

" \

B.tl.

1

:

1 "d.. n.

!

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

Fr stace.

Vc.l

,"1 -=======---

r..o.

- i

_ . J ~ : . - J

1

r

L 1

l:::::I c:=

(' S

!.1

=

.. - - -

1 ,.

r

-f J

... r

" f "T J'ti

f

i

-

L- a Ft

1:f

f

If f

(l. ....,) 1 ,..1.,1.

P. '",.11

en..' . 1{ , ..,.

y y

If

f .....

1\ ........... ...-1-.0(. .. ....

Vell: .'2.- C,.\,.le,

Il

"P

1

1

1

)

1

U...l i\\s.

1

.t:'

1

1

,....

,

:

:

1

1:=

:

1

!

r{hl f)

'J\.;' fi' . c....

et, .1

.,-

, ,.

* : U"'f)

... """'T"

:rh.! Il

ct, lai t

.',r=---".....

....

1 .H!1 ..........

,.....,...

l'\

-

t_ ......

'/1&.

--...

,.

...--...

-

----

..........

11, .....-;'\ ... ......-

--

......

L..J::F1

.--s

,

.- ..,..

---

F.N.

....,...

===--IP

- ~ . , .

f ....ff"'i.:"!"-. __.J'

,

1\ =

_.. ------------

----------

... - -

-- -. ------- ~

- ~ - - - -

i (l's..&..

~ ~ , .... ~ ~ - ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

( ~ c . . : - - - - - - ... ... .... - - - _. - - - - ... - - - - ...Ji

~ ( , , ~ .. ~ - - - - - -

..... ~ ~ ""' ,...----------

---

~ ...

:: -- 1:

,-

-

.....--.../

'r

n

If(t)

f-o.. .....

,

-

- .-

t

-.1 -

,... -. ..p-

1'_,

"

1

,,- -L. -l.... ,..-J....., f -I-

l'. .;-

v

0..;...") -L )

--!-.

, ri-

-;

(.Ica"...-.)

LI

=

r-5j\'

(Jcuctot-.)

lfP n.':' ___

1

--

1

l

_

.. ;

-.

""

f ........... ....

0...:--)

. .

-

.

- .-

. .

!Fr

-L .--S---,

... ,J

"

i i:

;,

-

,-r--,

i'

.1 il

(d.utcx..

f1f

/1'\

l.I"l" .It

y ....... y

"-

.1

'(/fP)

r"-.tf..

l'

l'frrr)

rf..... r ... l'

iCITP}

1

1'4' i'

1(f1f)

,:aa._

1 .L ..--"!!

,

....

-* '*

:$

- ..

$

l

FI.

00.

CL

-'10-

rrr

f'

\y

toJA-J6f

as.

f'

",

\Car... _1.

1

: '.A:

y

:Jl:

..

"

'JI.\

.

'(trf''''

1

/I1lA: r r

'J\1

l' 'Ctrr'

1

,--...

;:Q:" :..' =0:

'J\a..

1ClIr'

1

nN.<

+

r

'IC

ffP

)

Ft.

a.

--.

J"

J

-

-:1

'0 /--=Itr

1.1

-':.-=:M 1.

t'-...

---r

W '"---

.

.l

t1-'

1

-1'

!:

JIl._

,

1

t

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

: Jr 'J"'" ,..hl, r.-

l

",---

r.".1 llij Ir ""f'

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

B

--------"

'{(,J... -.. 1 1

,..-,

1

A.

1

"--

-

1 r--.I

."

"'""

0\.

'IL

..

Il r:/... 1

1

"

CL

Il,"'

... _-L

---

-

-1-'"

\') ....... ,. \ : ......

---

S.a.

"'7"'I..:.L:

-r

... 1

--

....

&te

, (M'

,.

_........_--- , -

LI/'I

._

1

n

-

1 .---

-

f .

P R J ~ : : :

~ ,

~ / 5 -

~ l b -

= = = - . . , ' - ~

f.H.

1pt

1bc.

l's.,L.

,:lM.

1b...

"f

-lD-

}

...

J

J

1

, __ ,,, ....,.' . 41'

l-=::::Rfr uuc. ...

b&

efll, 8 r. J.fKn...

: - - - - ; - - ~ - - - ~ - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- --:

5

.

F

R

J: r1!!

c..

T.

1

u''\;"

l'7'\f

Cl.

,

ll"'-rso

1ffPf! ...

.....-.

""

.a.

T. s,

" '!..1IQ

r.jl."

;.

...

[l8J

fi ...... l /:,,\/0" t'7\f

.K.

1 r

1 b

""=,,,-

ri

T.

;':'\,.

(f)

j.

? r:"..fO"

ri

<Ii

r

Il

pp

r':,r

1 r

,..

1 1

r:--W

Wb

f' (II)

..

fi

1 rJ-.V.

.,

1

FrM=M FFFfi9 Il

..:t..

7

"'f

D

f\ (JIl)

.

...

7

5

r

::

/7\10"

,

1

1"-

rI'

n "1

Il ,(dOlitU)

l'

"

"

-:.

t' t

rill.

1

f":"\

1(jBf)

1

p:4L11 Il

f\'"'....

n

--,..

.i

1"':\1

1jj)

1

r

'";.\

10 1':'\1

,.16. I,f .

116)

l'

;

]

/0-

,:zz. i:

f":\1..

.

1

.,

,:u.l11

I!" T1!:" :!:

l"':"'Jo

""\

r

p

tr-=====,'".k

.I

=J

/lff

"

:;0.

f "If :

"

"40'

"

=J=

,."

n

.

1

1

<If) '''f( tu'-"

l

f

-::-

.2

:"of

....

*

:r

it.:;(

=-/\

"-f' 1\"-"

-. qp'

.

.(,..l)

.

-r.

:".

T..

1

f

=

jW*

nt.

*'

a...- ....::::-.

"*

fff

"P __

=-

"

['\ .....

lfP

-

l' ..

if

'" L

-

)

'.,

1

f-+T

,

JJ

ft

'> ,,-l. ..,.

t\t

fIt

5

J,.(J.

!ID r-I-r .

1

7'-1 1

ta

'\ f

1

1 1

,

f.tf

Tr'

f C-.

1

,\a\ Cr\..MS: GlaUtl ...I! ho tar,J

.1.

pl.."n.

1 ..... 1.1.

"'f

t l,.-Jo ..

"f.

l.51.

;-'

f.,o.

f')I"'&.oV,

...

>" - __ 0

\J\.,.1.

'Il...

\).t

.7

(nr

l

,,- --. -- - - -.'

",f

.,.....

lf

'#.

9.... (fltJt(J ...

r------ -------- ---

\

>

(s...)

----------------- -------------------,

(nf'\

,

t.: ::.r ~ ...""

IJ\".\

(fW)

'1\1\.1

('If)

~ ...

CM)

~ c . l .

'O,s.

~

,

~ J g " ,

POcQ ~

't\ft.1

1

B

(,. roaL W-fI...)

(s!?tJ)

13

8

Fi.

5

8

~ - : - - - ~ - -

r

8

DL.

,'..

r

8

fj

8

---

"

========---11

====_--n

III

U. ~ u ~ . 1 . 11","T.

iF

rUt,1

" f r ~ ,

~

Pltt.l Tilt'lF-

.f

\3

B

ft

1

di

s... p

Il.

'1

si:

1

1

s.;... P

1

1

dit"

1" ...

"".

l ...

-

.

5

8

D.B.

)PCKO .. ps

\'P

\3

8

()I..

Cl.'

Cl-'-

Il

--

EH.

----

.... ---..

Trt

1n.

1\",

....,-

13

8

b

8

fi1z

11...

Vltt.2

1/

f.If,

VI,..

l,

rJ3b--

p"..,

5

8

~ 3 t ...

5

B

IW...

lYb.

,,----

5Jt M.M.

1 ,

p<:JJI::>

......A,- _

,v 39-

Y'\tl.:'"'..

"1 r:;--,

01.

i'i

V -.-.

-r-r J

J "fJ

1'-=.",; =-"f..:::::.f

"'f

=:::v.=-

1\.t.

rA LLJg0

PueJ. (tk.t 1

l''vr

"

-=::"J:;- -=: ...f:::-- -=::,.J::> c::::=,../..:::-

Cf)

'. ......... 1

1=====1

-.

i\1$-

0..a.;

1

f$

,

.. ..

fE

...

Cf)

-=::,J:::::-

c:::::=t4==-

c::::"J:::- c::::::,.J

A A A

"

1

. 1

----"

. .

;,.-- ......... ./ >- ----- ... _---

c=::::f :::::- tr -==.'"f :::=- p

-===-1\

___..-"'_ '--"" -- ", -- --'

tlfO(> .-::=:=."J;::::;- C:::::"J===-

-------r-=::::::!

===J

======-r ---== f

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

: . ~ , . , . I . . v .

o 1- Glk. ' ~ ~ 9

reec.. :5:!

-T Cft)

,

r'" (ff"

f1= tr .

k. - ---,

lA

1 -/.i'

.J

m'W

.......

1

tir' Ff=f :

1 .- .., ..

" .....

... 4

...1-==:::1

l:::J::S=' - , F

f -C::::::::::N-

i=-

Ir i1P

U&,'tt.\

J

1

'Clff)

,,...,

2

1

i'l

rlff

)

"I\.!.

lem)

1 1 n

'mt-

1 1

'f.}

Cli.

c.v.

-45-

Pn.

.,.

'i\n. \

'Iii.

'Jet

QIP)

':/ft

.-

-( fIf)

1

l

Crrl

. r-t",

-

--

....

..,.-

1 1

" 1 l ,', Il 1 1 1

=r'.

-

1-

"

-}

" ....::::: --=.J ,,-=.1_

iI-::- 1- -

-- -

..Ji'; =-;=

1,

,.sL

'1 1=1 ===

...=;:::, fi'

,-

1 1 cr.

J

If

-"J==-,.... J_.... _-p

.1:1

a-:::I ..L.

-

_-!-

-

l' ..... -_ ....... .,_. .._.........

... lt

_or .. tlf'la.!'_

- Fr -,.J=-ff

- ".f==-tt'-

-=) ===-p ,..I=-

1

_....-

,.---

1

6- 1 J::

J

-'

11' 1

Il

----

t-..... O...c

a- I

.'2

:-

1

1

-

1 1 1

------1"-

'fff

1

-' 1

Il

=-

1 1 1 1 1

--

--t"

0

l.

.

1

.

ri

i

fi' --

1

1 1

.S.

'l.)

c.".

CIr.

Rit. ,,\ Fine. ...

li.

-

B

:Z,

lr

'-1.

l

( J

1 t 1 . 1 .

L::-

----'-;;;,::: ...... T_--;;:: ,,_....... _""L.

_.....

JI'

/1

"-="'f

--=:'--r "

fP.

T

I=-f

Cf)

1

f

,

1 ...

-

-

_ln

1_'-

.....

1

;-

,

-

;Tir

'"

...

=5=-P

Cf)

f r f

'"

LI o.'

1

T"T

>11

,,,

2

Tf'"

>rt

1\

--- )Ill

""\

l.

'la)

1ft.

1\n.

-

B:l1...

~

",

-

1\,..

l

=

/lff

~ . 8 .

Analysis

Introduction

Queezinart-hocket in a blender is a composition for eighteen players-five

woodwinds, five brass, two percussionists, piano, two vioiins, viold, cello dnd

double bass-with a duration of approximately fourleen minutes. The title has

no relevance to the musical materials in the piece; it is a title chosen so as not to

impose presupposed programmatic ideas and/or emotive qualities on the

listener. Therefore, the piece has no subjective meaning-it is simply a flow of

musical events. One could suggest that the title implies the existence of 'hocket-

like' material in the work, but this material would be 'minced' and scattered due

ta the fact that it has been fed to a blender, in a figuraI manner, of course. This,

then, leaves the listener confused with respect to the dispersed appearance and

the function of the 'hocket-like' material, and more importantly, leaves the

listener at 'square one' -deciding how to listen ta the piece. Furthermore, the

absence of presupposed conditions forces one to listen actively to the immediate

characteristics of the piece as it unfolds-timbre, forro, rhythm, dynamics, etc.

The non-programmatic title is important insofar as it imposes on the

stener the important issue of the piece-'figures.' Figures can be described as

the movement of sound in a multi-dimensional process. The figures in this piece

have a dual role in respect to how they are structured and how they function in a

large-scale forme Firstly, the figures in this piece undergo slow and gradua!

so

metamorphosis within sections, and on a larger scale, from section to section.

Secondly, the figures are created in such a way that they distort and manipulate

perceived time. The unification and interplay of these two ways in which

figures behave in this work establishes a form, one which acts as a co-dependent

third factor in a multi-dimensional web of interrelated elements working

together to cause the manipulation of perceived temporality. Before tackling the

specific figurai details that enable musical temporal manipulation in each of the

six sections in Queezinart - hocket in a blender, it is necessary to discuss how

figures can manipulate and distort perceived time.

Manipulation of time

A key influence in composing Queezinart-Itocket in a blender, with respect

to the manipulation of perceived time, is the theoretica1 and psychological

philosophy of music termed. 'complex.'l A major composer of 'complex' music is

Brian Femeyhough (b. 1943), a composer who often strives to distort perceived

time in his work. One of the reasons this music is labeled 'complex' is due to its

'information.-overload' auraI quality. Barbara R. Barry believes that the more

'effort' required to process a multitude of complex musical events the more time

the listener believes has gone by; she has termed this The Tenlpo/Density TIzeary.2

Most often, when music is 50 densely written with respect to rhythms, dynamics,

1 This music is also referred to as '6New Complexity."

2 Bmbara R. Barry, }Vlusical rime: The Sense o/Order (Stuyvesanr. NY: Peodragon ~ 1990), 181.

51

attacks, and timbres within a multitude of simultaneous figuraI processes, the

brain can not 'catch up,' thereby distorting and lengthening the natural sense of

time; this "constantly creates situations which are psychically rather than

physically exhausting."3 This occurs when 'clock' time, or the internally

constant, natura1 human time of reference-heart rate, rate of breathing,

adrenaline flow- is distorted due to the swarm of audible information in a

multi-dimensional frame. Femeyhough has said that this can accur in music

where IIthe relationship between the rate of harmonic change and the density of

surface figuration...encourage[s] the mind ta move 'toc fast' and, as a resulf:r

find itself constantly pulled up short by the slightly counterintuitive viscosity of

information presentation."4 Though this is true, it must be clarified that

Il complex perceptual states arise, not from the quantity of discrete particles

distinguishable therein, ... but by reason of the perspectival causal energies with

which they are invested as a result of the intersection, irnpingement and mutual

transformation of linear processes in momentary successive or overlapping

chaotic vortices of perturbance."5 More simply, the perceptual distortion of time

Il does not correspond ta the amount of information presented, but has more to do

with contextual relationships, and with the quality of mental structures derived

3 Richard Toop. "On Perspectives ofNew lvlusic 31. No. 1(Winler. (993), 55.

James Boros, -Composng a Ytable (IfTransitory) Self-Brian Femeyhough in conversation with James

Boros," Perspectives ofNew Music 32, No.l (Winter, 1994), 123.

s Brian inAsthetik und Komposition: lur Aktualitat der Darmstadter

Ferienkursarbeit, Darmstadter Beitrage 20 (Mainz, 1994), 18.

52

from the surfaces by the listener."6 It is at this point that the manipulation and

distortion of tinte becomes an objective entity:

When we listen intensely to a piece of music there are moments when our consdousness

detaches itself from the immediate flow of events and comes ta stand apart, measuring,

scanning, aware of itseHoperating in a "speculative time-space" of dimensions different

from those appropriate ta the musical discou.rse in and of tself. We become aware of

the passing of time as something closely approaching a physicaL objectivized presence.

7

The only way in which manipulation and distortion of tinte can take place

is through the retention of stimuli. Robert E. Ornstein, a psychologist who has

studied and conducted experiments on the manipulation of perceived time,

believes that the manipulation of experienced time must involve:

8 memory of the entire intervaL longer than the tleeting 'input register' storage. The

time-order effect shows that any approach 10 duration experien must he a storage one,

oot merely an 'input register' type. These theories are of similar arder, the only

difference being that the 'input register' holds that duration experien depends on the

input information during the intervaL while a storage approach holds [!hatl the

information remaining in storage determines duration experience. 8

In other words, it is the memory of events that is a crucial factor in the distortion

of perceived time. Also, the degree to which experienced time will be

lengthened depends on the size of space required to retain stimuli:

It takes more space to store new events, 50 that an increase in the number of events in an

interval should increase storage sZe and lengthen the experience of duration of that

interval. It aJso takes more space ta store increasingly complex events (in the

information theory sense) 50 the experience of duration should lengthen as the

complexity of the stimuli or of the sequence of stimuli increase.

9

6 James -Why Complexity-Part Two (Guest Editor's Introduction)," Perspectives ofNew .\'Iusic

32, No.!. (Winter. (994),91.

7 Brian Taetility ofTime (Darmstadt Lecture Perspectives ofNew Music 31,

NO.l (Winter, 1993). 21.

8 Roben E. On the Experience o/rime England: Penguin Books. 1(69), 104.

9 Ibid., lOS - 106.

53

The manipulation and distortion of tinte in QueezinaTt-hocket in a blender

is based on the discussions above regarding the manipulation of time. As far as

the distortion of perceived time is concemed, a distinction must he made:

'figure' is, in a way, related. to 'texture', but there is an important difference. To

manipuIate perceived tinte, one must not regard the movement of sound as

'texture.' A single, global view of a mass of musical information (texturaI

listening) negates any chance for there ta exist any distortion of perceived tinte.

On the other hand, when one listens ta a mass of musical information as

inrwoven and interrelated. non-linear sound abjects in motion, then time

distortion might accur. It is the intent in Most of the six sections of this piece to

start at a lowand static degree of perceptual temporal distortion, increase to a

higher degree, and then decrease back down ta a lower degree. In other words,

the figures expand the perceived duration of each section by a length generated

due ta the activity and density of musical information. The degree to whieh

experienced tirne will he lengthened ultimately rests on the listener's musical

ability. An experienced listener will retain more of the specifie details of musical

ideas and figures for a longer period of time-thereby increasing the degree of

perceived tirne distortion- than an inexperienced listener. As mentioned earlier,

the way in which time is manipulated in this piece is dependent on the figures:

activity in the individual voices (linearly), activity in general (vertically/ non-

linearly), orchestration (timbres involved), dynamics, register, short and long

notes, etc.. Though the figures and perceived temporal distortions change

54

slowly and gradually, thereby naturally blurring sectional articulations, formai

divisions are appended here for analytical purposes:

Section A: mm. 1 - 37

B: mm. 38-81

C: mm. 82 -106

D: mm. 107 -146

E: mm. 147 -159

F: mm. 160 - 183

Sectional analysis

In the following discussion, the musical activity of the figures in each of

the six sections will he examined, in order to show how these figures generate

perceived temporal distortions.

Section A- mm. 1 - 37

Section A is in two parts. The first part (the opening of the piece) begins

with the muted tuba playing a two-note motive, a descending semitone in the

low register. This motive appears throughout the work, performed only by low-

register instruments. The motive is augmented by the addition of instruments,

and is itself developed into longer, 'extended' motives. As instruments and

ss

instrument familles 'pass' the 'extended' motives back and fortlt in mm. 1 - 15,

the figure begins to feel more and more unstable. In cornposing this figure, the

notes for each instrument (linearly), were selected somewhat randomly, though

favoring tritones, semitones and thirds. The rhythms were chosen with

awareness to physical and technicallimits of each instrument The overall intent

in mm. 1 - 16 was to create the illusion that the lwo-note motive had multiplied

infinitely.

In mm. 14 - 15, the cello abandons its original figure to bring us ioto the

second part of Section A, mm. 16 - 37. The primary focus of this second part is

the 'centralization' of the note e; the cella initiates this activity in m. 16, joined by

the viola in m. 19, and the two violins in m. 20. The strings 'centralize' around

the e by attacking and sliding between e and their upper and lower quarter-tones

until m. 32 The note e was chosen because of the violin's double..stop capability;

e-natural is produced on l (sul E) and the upper and lower quarter-tones of e are

produced on fi (sul A), thereby blurring the pitch. The upper woodwinds and

trumpet join the 'centralization' of e in mm. 23 - 37, thereby overlapping and

completing the 'centralization' in the second part of Section A. In the

'background,' the instruments from the first part of Section A (minus the cella)

reiterate the two-note motive from the first part of Section A, although here they

attack together.

It should he noted that in Section A, four rhythms which are closely

related are introduced; these enter again at different points in the piece: a) the

56

two-note motive, b) a series of 'random' notes in continuai rhythm, c) the two-

note motive with the second note held, and finally, d) a repeated note, with the

duration of rest between each successive entry gradually increasing.

~ .

As the activity increases in mm. 1 - 16, the perceived tinte is lengthened

due to the amount of information being processed; the countIess pitches,

dynamics, instruments, timbres, rhythms, etc., gain in activity and momentum

thereby forcing the expansion of experienced time. As the listener tries ta accept

perceptually the processes and relationships of aIl the musical elements, the

mind can not 'catch up' to the abundance of information, thereby making the

mind believe that more time had passed than actually did. However, by

'centralizing' e at m. 16, the listener may feel a retum ta 'clock-time' frOID

lengthened perceived time. This'centralization' of e is far more stable

harmonically compared ta mm. 1 ... 15, where there is no pitch center. On the

other hand, the lengthening of perceived tinte may continue into the second part

of Section A due to the Many unstable frequencies being projected from the

57

quarter-toRes. Nonetheless, perceived tirne retums to 1 elock-time' as the activity

gradually slows to a statie end in m. 37. Therefore, the perceived temporal

distortion and lengthening started at a very low leveI, proceeded to a very high

level, and retumed ta normal.

Section B-mm. 38 - 81

The transition into Section B from Section A is very smooth; the two

violins, viola and cello hold lgh harmonics into Section B. In mm. 38 - 44, the

piano plays short ideas that never develop. Beginning in m. 44, emphasis is

placed on strict sectional writing as the woodwind, brass and string sections

perform their own figures for the remainder of the section, as the piano and

percussion help punctuate attacks and fil1 out the timbre. The writing is

arranged so that the focus jumps between the instrumental groups. The shift of

attention between the three figures ereates a larger 1 conversation-like' figure. As

two figures diminish in activity and dynamics, the remaining figure is brought

ta the foreground. In m. 68 the three instrumental groups continue similar

material from before, but now without regard to each other' s activity, meaning

that the three figures act independently from each other. The three figures in

mm. 68 - 75 are somewhat similar; nine-tuplet groupings are used. In m. 75, all

instrumental groups, except brass, have nine-tuplet groupings, and on beats

S8

three and four of that measure, the nine-tuplets are grouped by six to set up the

climactic 6/8 meter in m. 76. Two pauses then occur for contrast and relief.

The pitches used in Section B are, linearly, far more chromatic (by haIf-

steps) than in Section A. AIso, with respect pitch organization, in m. 68 the brass

section introduces a I2-tone series:

~ Ii- .,.,wg

Each sequentiai entry is the next note of the series, and the dynamics increase for

the first three of four repetitions of the series. This 12-tone series is one of four

12-tone series heard in the piece, but the first four notes of this particuJar series

become very important in Section C, and for the remainder of the piece.

Perceived time slowly and gradually lengthens in Section B, due ta the

continuaI addition of layers of activity, but there is a retum to 'clock' time at the

frrmati in the last two measures of the section due to the lack of aurai stimuli

during the fermati. The transfer and transaction of figures in the foreground

enables the manipulation of time. The kind of' roller coaster' transfers of figures

being forced into the foreground and, in mm. 68 - 75, the addition of

independent figures performed simultaneously, causes the mind to believe more

time has passed. It is because the three different figures are constantly emerging

into the foreground that the mind must constantly work to shift its focus onto the

different figures, thereby extending perceived temporality.

59

Section C-m. 82 -106

The function of this section is transitional, i.e., the movement from Section

B to Section D. There are two new musical ideas that are introduced in this

section.. Firstly, sequences of unison notes are implemented as a contrast to the

first two sections. In m. 82, several instruments play a unison line but sorne of

the notes in the line are held. This idea appears, though varied a little, in the

brass, double bass and piano in mm. 90 - 97. The idea finally comes to be

realized in its entirety in the flute, two clarinets and piano in m. 93, and joined

by the bassoon and oboe in m. 98. The second musical idea introduced in

Section C is the use of 12-tone series. There are four unrelated 12-tone series

employed in this section:

o.) ~ . b . ! i 5 ~ ~

The first four notes of the first 12-tone series appear throughout this section. The

a, b-flat, d and e first appear in this section in m. 85, in the crystal glasses,

percussion, and piano. The four notes appear as a chord in ffi. 87 in the tw'o

vialins, viola and cella. These strings then continue by making glissandi betw'een

the four notes of the chard, re-bowing every chord note. The entirety of the four

60

12-tone series begins in m. 93 and ends in m. 106. The introduction of ronning

16

th

notes in the piano and woodwinds in m. 96 prepares for the musical events

in Section D.

Although there are 3 layers of figures in the Most dense part of Section C,

the listener will perceive the passing of time close to 1clock-time.' By

systematically repeating musical ideas, the figures involved are straightforward

and not complex ta process mentally; for example, the brass, double bass and

piano stack notes to form chords that recur every measure, in mm. 90 - 97. In the

same way, with respect to repetition of material, the glissandi in the strings in

mm. 88 - 96 repeat consistently. The only malerial that couJd cause the

lengthening of perceived time is the running l6

th

notes in the woodwinds and

piano, in combination with the other two figures-mm. 93 - 97. The running 16

th

notes themselves will not cause tao much temporal distortion due to the fact that

the tempo is slow enough (quarter note = 50, at m. 98) that each and every note

will be heard and easily processed, and, aiso due ta the fact that the 16

th

notes

are not broken; there are no rests inserted to create an unpredictable figure.

Section D-mm.107 -146

There are two parts in Section 0; mm. 107 - l35, and mm. 136 - 146.

Section D is the middle of the piece, approximately near the 7'30" mark. With

61

this in mind, a change in time signature seemed appropriate. In a way, it is also

a change of pace. The halving of the beat unit from a quarter to an eighth

represents an illusion to a quicker tempo. The time signature changes here take

the form of a palindrome: 9/8-5/8-7/8-6/8-13/8-6/8-7/8-5/8-9/8. It

seems only fitting ta set these time signatures into a palindrome at the center of

the work. Not only does this pattern repeat three tintes, thereby forming its own

palindrome, but formally, the main sections of the piece form a palindrome.

This will become apparent in the discussion of Sections Eand F.

The musical malerial in the three repetitions of the palindromic rhythmic

cycles is very simiIar in that all three are based on the 'unison' figure from the

previous section. With each successive repetition, the 'unison' figure takes on a

new timbre, and because of the simiIarity in pitch structure, the figures simply

expand through addition. The section begins with the solo clarinet; the second

clarinet plays when the first clarinetist 'should' breathe, as the intent is to have a

seamless musicalline until the fiute and oboe entry in mm. 113 - 114. The same

four 12-tone series are used as in the previous section, which provides a natural

and smooth continuation froID Section C ioto Section O. In mm. 116 - 124, in the

first repetition of the rhythmic cycle, the upper strings, percussion and piano

take over and extend the 'unison' figure, but the sequence of pitches is not part

of the 12-series used earlier, in mm. 107 - 115.

62

In the second and final repetition of the rhythmic cycle, mm. 125 - 133, the brass

and percussion enter with a starldy contrasting timbre. Despite the shift in

timbre, the brass continues the extension of the 'unison' figure. The third

rhythmic cycle ends in rn. 133, but the 'unison' figure continues into what seems

to he another repetition of the rhythmic cycle-the 9/8 and 5/8 in mm. 134 -

135-but another cycle does not begin. If the pattern of tirne signature changes

could he aurally received and decoded, then the ear and mind would he fooled

in predicting the continuation of a complete new cycle beginning in m. 134. As

the 1 unison' figure cornes ta a close, the second part of Section D begins, mm. 136

-146.

The second part of Section D acts as a transi tion ta Section E. Alter the

cacophonous ending of the first part of Section D, a more stable and calmer part

is required in order to lead smoothly to Section E. In mm. 139 - 146, the

foreground is represented by the oboe and muted trombone solo, doubled at the

octave, which serves to continue the section'5 emphasls of lines at the unison,

while other instruments support the solo through small dynamic swells, to

which the percussion adds tremolos. This 'calm after the storm' also serves to

lower the general register, 50 as to lead smoothly towards the low register at the

beginning of Section E.

One of the ways in which perceived tinte will he altered is caused by the

time signature changes. When the meter constantly shifts, the listener May feel

lost. Ornstein has found that "more 'organized' experiences were estimated as

shorter than disorganized ones. In storage size terms, a situation which was

63

'organized' would need less space in storage than a 'disorgani.zed' one."IO

Compared ta the previous tinte signature (4/4), the listener bas no strong sense

of the downbeat, making it difficult to predict or anticipate the nexl Beginning

in mm. 107 - 115, perceived tinte maintains relatively close to 'cteck-tinte.' This

begins to change at m. 116 where the entries of the woodwinds and percussion

are unpredictable (in addition to the meter changes), and in the same manner,

the entries of pitch patterns in the upper strings. The addition of layers, and

increase in activity in the percussion in mm. 125 - 135, will aiso cause the

listener's experienced time ta lengthen. Although the perceived tinte will

lengthen, the amount will not he as great as in Sections A or B. AIso, the use of

'unison' figures provides a sense of harmonie stability, with whieh the listener

will feel eomfortable, even though the note patterns are chromatic and atonal. In

mm. 136 - 146, the passing of perceived tinte should gradually return back ta a

stable 'clock-time' due to these two elements: a solo doubled in octaves, and the

relatively static activity in the background.

Sections Eand F-mm.147 -159, mm. 160 -183

Beginning in ffi. 147, there is a retum ta figures similar to those heard

previously in Section A. AlI of the rhythmic patterns employed in Section A (See

p. 57), are now involved in mm. 147 - 156. In m. 155, the flute, oboe and upper

\0 O m s t e ~ 77.

64

strings continue the upward motion initiated by the brass. As the brass ends in

m. 156, these higher pitched instruments continue the registraI a s c e n ~ in a

different manner from the brass only in that the notes are slurred. This registrai

ascent only serves ta provide a smooth transition ta Section F.

In Section F, beginning in m. 160, there is a retum ta figures heard in

Section B. The piano solo is in the upper register, prepared by the registrai

ascent in the previous section, and is supported by the crystal glasses, harmonies

in the strings and a low c in the double bass. The piano's registraI descent in

mm. 167 -168 prepares the retum of the low figures previously heard in Section

A The muted Iow-brass figure, against which the continuation of the string

harmonies and crystal glasses are juxtaposed, descends chromatically with every

repetition of the 'rhythmic pattern,' except for the first Acting more as a musical

'link' than an object of juxtaposition to the low figures, is a muted trumpet that

descends chromatically every measure. In mm. 172 - 176 the two violins, viola

and cella play descending glissandi, which can be viewed. as a continuation

and/or addition to the chromatically descending figures in the brass. In m. 175

the two-note motive makes its final return as it concludes the work. An

interesting event occurs rhythmically in mm. 176 to the end. Though linearly

structurally intact, the repetition of the two-note motives takes the form of

rhythmic pattern "d"(p. 57); therefore, in addition to rit. al Fine and decrescendo,

there are greater rests between entries of the motive. The two-note motive

65

appears less frequently through tinte, thereby aIso resembling rhythmic pattern

1/ d":

",

,

J _

114

R

1==--,

Cf)

f

,

1 . I!!r

- -

1\ __

,

\ ...

-

;;

1

r;

-

ln f

-

-

-

:;r

V

\.n

-

The work concludes with a final statement of the two-note motive played by the

muted tuba.

Though the musical materials and events !n Sections E and F are almost

identical to those of Sections A and B, perceived lime will not he affected as

much as the first hearing. It is because the musical events are so similar, that in

the 'second hearing' of these events, the listener will have already heard the

material, and will he able to process the information far more quickly. Ornstein

believes that one way in which a "given stimulus situation is changed is by its

repetition."11 He terms the repetition an 'automatic' stimulus situation. When

repeating a stimulus, Little memory space is needed (as the stimulus is already

there), and our awareness for new activities decreases. Therefore, there is Little,

if any, distortion of perceived time in Sections E and F. An event that is

perceptually interesting, though does not concern the manipulation of perceived

Il 73.

66

lime, is the very end. As the two-note motives become more sparse linearly and

non-linearly, the anticipation of the next becomes heightened. As the last two-

note motive sounds, almost two complete silent measures are conducted. The

listener is waiting for the next tuba entry, and is wondering if there will be

another. Nonetheless, the piece ends as it started.

Relationships within global form

As mentioned earlier, palindrome plays a role in this piece. Palindrome,

as a device, exists in Section D as an organization of tinte signature changes, and

it aIso exists as a large-scale structural device of constraint ta provide an method

of recognition and ability to 1 folIow' the motion and progression of figures

within the piece. Given this, the piece has an ABA' large--scaie forme One of the

main determining factors of this form is the way in wruch pitch is used. In A

and A', the pitches are randomly chosen on the Most part, as opposed ta B,

where the pitch selection follows a predetermined system.

67

Bibliography

Barry, Barbara R.. Musical Time: the sense ofarder. Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon

Press, 1990.

Boros, James. "Composing a Variable (H Transitory) Self- Brian Femeyhough in

conversation with James Boros." Perspectives of New Music 28/2 (Win.

19(4) 114 - 130.

Boros, James. IIWhy Complexity? Part Two (Guest Editor's Introduction)."

Perspectives afNew Music 32/1 (Win. 1994) 90 -101.

Femeyhough, Brian. "ParaUel Universes." in Asthetik und Komposition: Zur

Aktualitat der Darmstadter Ferienkursarbeit Dannstadter Beitrage 20

(Mainz, 19(4) 17 - 22.

Femeyhough, Brian. "The Tactility of Tinte." Perspectives of New Music 31/1

(Win. 1993) 20 - 30.

Friedman, William. About Time: Inventing the fourth Dimension. Cambridge, MA:

The MIT Press, 1990.

Gabrielsson, Ali, Ed.. Action and Perception in Rhythm and Mlisic. Stockholm:

Kungl. Musikaliska akademien, 1987.

Gorman, Bernard S., and Wessman, Alden E., Eds.. The Personal Experience of

rime. New York: Plenum Press, 1977.

Hartocollis, Peter. Time and Timelessness, ar, The Varieties of Tenlporal Experience.

New York: International Universities Press, Inc., 1983.

Hasty, Christopher F.. Meler as Rhythm. New York: Oxford University Press,

1997.

Kramer, Jonathan. TIte rime of Mllsic: new nleanilJgs, new temporalities, new listening

strategies. New York: Schinner Books, 1988.

Ornstein, Robert E.. On the Experience afTime. Middlesex, England: Penguin

Books, 1969.

Toop, Richard. liOn Complexity." Perspectives of New Music 31/1 (Win. 1993)

42 - 57.

68

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Beavis and Butthead ManualDocumento15 pagineBeavis and Butthead Manualbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Writing Scientific Documents With Latex PDFDocumento12 pagineWriting Scientific Documents With Latex PDFbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rosen Han 1973Documento9 pagineRosen Han 1973AoiNessuna valutazione finora

- E Book Handbook For Spoken MathematicsDocumento63 pagineE Book Handbook For Spoken MathematicsVishal AryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Freedman 2016Documento4 pagineFreedman 2016bigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Art of Spiritual Harmony 00 KandinskyDocumento170 pagineArt of Spiritual Harmony 00 Kandinskybigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Flight RevisitedDocumento14 pagineFlight RevisitedRicardo JaimesNessuna valutazione finora

- Gawker Bankruptcy FilingDocumento24 pagineGawker Bankruptcy FilingMotherboardTVNessuna valutazione finora

- Svoboda Van Howe Circumcision A Bioethical ChallengeDocumento6 pagineSvoboda Van Howe Circumcision A Bioethical Challengebigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Adler FormattedDocumento45 pagineAdler Formattedbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Blank Slate, The Noble Savage, and the Ghost in the MachineDocumento22 pagineThe Blank Slate, The Noble Savage, and the Ghost in the Machinebigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Circumcision and Your Legal RightsDocumento2 pagineCircumcision and Your Legal Rightsbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- "These Boots Are Made For Walking": Why Most Divorce Filers Are WomenDocumento44 pagine"These Boots Are Made For Walking": Why Most Divorce Filers Are WomengssqNessuna valutazione finora

- Imslp34175 Pmlp03546 Wagner Wwv090.01arsingerdDocumento6 pagineImslp34175 Pmlp03546 Wagner Wwv090.01arsingerdbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- 17 Bayesian Truth SerumDocumento5 pagine17 Bayesian Truth Serumbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Word2vector Paper PDFDocumento9 pagineWord2vector Paper PDFujnzaqNessuna valutazione finora

- Jim Schulman's Guide to Choosing Water for Coffee MachinesDocumento17 pagineJim Schulman's Guide to Choosing Water for Coffee MachinesJorge TenaNessuna valutazione finora

- History Intel CPUDocumento31 pagineHistory Intel CPUVincent SikhalaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1507 07998v1Documento8 pagine1507 07998v1bigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Kang Memoryforum14Documento4 pagineKang Memoryforum14bigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Crim HarassDocumento64 pagineCrim Harassbigbigbig90003270100% (1)

- Soylent 2.0 Release NotesDocumento2 pagineSoylent 2.0 Release Notesbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- WW DS Q2-16 ThinkPad P70 FinalDocumento2 pagineWW DS Q2-16 ThinkPad P70 Finalbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1405 4053v2Documento9 pagine1405 4053v2bigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- DRAM Errors in The Wild: A Large-Scale Field StudyDocumento12 pagineDRAM Errors in The Wild: A Large-Scale Field StudyeverydaypanosNessuna valutazione finora

- Circumcision Your Legal RightsDocumento2 pagineCircumcision Your Legal Rightsbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Proc. R. Soc. B 2011 Klimentidis 1626 32Documento7 pagineProc. R. Soc. B 2011 Klimentidis 1626 32bigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- G Joni FiledDocumento20 pagineG Joni Filedbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Acadcorrections Made Dove Press Formatted FinalDocumento30 pagineAcadcorrections Made Dove Press Formatted Finalbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- Konrad Zuse's First Computer, the Z1: Architecture and AlgorithmsDocumento24 pagineKonrad Zuse's First Computer, the Z1: Architecture and Algorithmsbigbigbig90003270Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Liszt S Symbols For The Divine and The DiabolicalDocumento22 pagineLiszt S Symbols For The Divine and The Diabolicalfloren arizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Antonio Soler - His Life and WorksDocumento3 pagineAntonio Soler - His Life and WorkspdekraaijNessuna valutazione finora

- ABELE Trad ALWYN The Violin and Its History 1905. IA PDFDocumento156 pagineABELE Trad ALWYN The Violin and Its History 1905. IA PDFAnonymous UivylSA8100% (2)

- La CaliffaDocumento2 pagineLa CaliffaJosé Navea LeónNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter One QN 1-25. What Should First-Time Entrepreneurs Know Before They Launch? What Should Entrepreneurs Know Before They Commit To Launching Their Firm?Documento11 pagineChapter One QN 1-25. What Should First-Time Entrepreneurs Know Before They Launch? What Should Entrepreneurs Know Before They Commit To Launching Their Firm?AdinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Roland GR-55 FLOORBOARD - HELP - 1502251Documento118 pagineRoland GR-55 FLOORBOARD - HELP - 1502251marinrebic100% (1)

- Handel and The Violin PDFDocumento9 pagineHandel and The Violin PDFAnonymous Cf1sgnntBJNessuna valutazione finora

- Liszt and Verdi - Piano Transcriptions and The Operatic SphereDocumento77 pagineLiszt and Verdi - Piano Transcriptions and The Operatic SphereMody soli-men-lvNessuna valutazione finora

- Sound Studies and Sonic Arts: Computational Listening - Seminar Jasmine GuffondDocumento4 pagineSound Studies and Sonic Arts: Computational Listening - Seminar Jasmine Guffondee dfsdNessuna valutazione finora

- SESSION GUIDE Grade 7-MUSIC (Form)Documento13 pagineSESSION GUIDE Grade 7-MUSIC (Form)Pilo Pas KwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Cancer - My Chemical Romance ChordsDocumento2 pagineCancer - My Chemical Romance ChordsHartono KasirunNessuna valutazione finora

- Underworld2 - 5m2b Heli Ride - Track On Beltrami SiteDocumento21 pagineUnderworld2 - 5m2b Heli Ride - Track On Beltrami Sitekip kipNessuna valutazione finora

- Herring Clarinet PDFDocumento9 pagineHerring Clarinet PDFAndrea BovolentaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chord Progressions For GuitarDocumento3 pagineChord Progressions For GuitarTeodoroNessuna valutazione finora

- Women's Pioneering Roles in Hip HopDocumento1 paginaWomen's Pioneering Roles in Hip HopRoger FolkloricoNessuna valutazione finora

- Merriam Anthropology Music Chapter 1Documento10 pagineMerriam Anthropology Music Chapter 1PaccorieNessuna valutazione finora

- Kenny Dorham 30 CompositionsDocumento49 pagineKenny Dorham 30 CompositionsRezahSampson97% (35)

- Medieval Music PeriodDocumento6 pagineMedieval Music PeriodJamaica Faye NuevaNessuna valutazione finora

- 10Documento51 pagine10Lourdes VirginiaNessuna valutazione finora

- BiosDocumento2 pagineBiosBenjamin ColdNessuna valutazione finora

- 70-Masquerade Is OverDocumento4 pagine70-Masquerade Is Overizdr1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rhythm, meter, and chord analysisDocumento6 pagineRhythm, meter, and chord analysisGrace JamesonNessuna valutazione finora

- Advanced Strumming ExercisesDocumento1 paginaAdvanced Strumming ExercisesStefanos Liasios50% (2)

- Netra Thesis PDFDocumento83 pagineNetra Thesis PDFMayank SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Hindustānī Sangīt Paddhati The System of Hindustānī Music V - 1Documento15 pagineHindustānī Sangīt Paddhati The System of Hindustānī Music V - 1khegdeNessuna valutazione finora

- 2012 CatalogueDocumento252 pagine2012 Cataloguesrdjan_stanic_1Nessuna valutazione finora

- NCT 127 Regular English Version SongDocumento5 pagineNCT 127 Regular English Version SongGeet ShresthaNessuna valutazione finora

- !infoDocumento2 pagine!infoBen NYNessuna valutazione finora

- ESL Games For Advanced Students - TRIVIADocumento31 pagineESL Games For Advanced Students - TRIVIAAndrea Santo100% (2)

- 8 Mapeh: Grade SubjectDocumento4 pagine8 Mapeh: Grade SubjectReggie CorcueraNessuna valutazione finora