Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Vedkalin Science A Short Article

Caricato da

akabhijeetTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Vedkalin Science A Short Article

Caricato da

akabhijeetCopyright:

Formati disponibili

`Veda' means knowledge.

Since we call our earliest period Vedic, this is suggest ive of the importance of knowledge and science, as a means of acquiring that knowledge, to that period of Indian history. For quite some time scholars believed that this knowledge amo unted to no more than speculations regarding the self; this is what we are still told in som e schoolbook accounts. New insights in archaeology, astronomy, history of science and Vedic s cholarship have shown that such a view is wrong. We now know that Vedic knowledge embraced physics, mathematics, astronomy, logic, cognition and other disciplines. We nd that Vedic science is the earliest science that has come down to us. This has signicant implications in our understanding of the history of ideas and the evolution of early civilizations. The reconstructions of our earliest science are based not only on the Vedas but also on their appendicies called the Vedangas. The six Vedangas deal with: kalpa, perfor mance of ritual with its basis of geometry, mathematics and calendrics; shiksha, phonetic s; chhandas, metrical structures; nirukta, etymology; vyakarana, grammar; and jyotisha, astro nomy and other cyclical phenomena. Then there are naturalistic descriptions in the variou s Vedic books that tell us a lot about scientic ideas of those times. Briey, the Vedic texts present a tripartite and recursive world view. The univers e is viewed as three regions of earth, space, and sky with the corresponding entities of Agni, Indra, and Vishve Devah (all gods). Counting separately the joining regions lead s to a total of ve categories where, as we see in Figure 1, water separates earth and re, and air separates re and ether. In Vedic ritual the three regions are assigned dierent re altars. Furthermore, the ve categories are represented in terms of altars of ve layers. The great altars we re built of a thousand bricks to a variety of dimensions. The discovery that the details of the altar constructions code astronomical knowledge is a fascinating chapter in the history of astronomy (Kak 1994a; 1995a,b). In the Vedic world view, the processes in the sky, on earth, and within the mind are taken to be connected. The Vedic rishis were aware that all descriptions of the universe lead to logical paradox. The one category transcending all oppositions was terme d brahman. Understanding the nature of consciousness was of paramount importance in this vi ew but this did not mean that other sciences were ignored. Vedic ritual was a symbolic retelling of this world view. Chronology To place Vedic science in context it is necessary to have a proper understanding of the chronology of the Vedic literature. There are astronomical references in the Ved

as which recall events in the third or the fourth millennium B.C.E. and earlier. The rece nt discovery (e.g. Feuerstein 1995) that Sarasvati, the preeminent river of the Rigvedic time s, went dry around 1900 B.C.E. due to tectonic upheavels implies that the Rigveda is to be d ated prior to this epoch, perhaps prior to 2000 B.C.E. since the literature that immediatel y followed the Rigveda does not speak of any geological catastrophe. But we cannot be very precise about our estimates. There exist traditional accounts in the Puranas that assign greater antiquity to the Rigveda: for example, the Kaliyuga tradition speaks of 3100 B.C .E. and the Varahamihira tradition mentions 2400 B.C.E. According to Henri-Paul Francfort (1992) of the Indo-French team that surveyed this area, the Sarasvati river had ceased to be a perennial river by the third millennium B.C.E.; this supports those who argue fo r the older dates. But in the absence of conclusive evidence, it is prudent to take the most conservative of these dates, namely 2000 B.C.E. as the latest period to be associated with th e Rigveda. The textbook accounts of the past century or so were based on the now disproven supposition that the Rigveda is to be dated to about 1500-1000 B.C.E. and, therefor e, the question of the dates assigned to the Brahmanas, Sutras and other literature rem ains open. The detailed chronology of the literature that followed Rigveda has not yet been worked out. A chronology of this literature was attempted based solely on the internal astronomical 2 evidence in the important book \Ancient Indian Chronology" by the historian of s cience P.C. Sengupta in 1947. Although Sengupta's dates have the virtue of inner consis tency, they have neither been examined carefully by other scholars nor checked against archa eological evidence. This means that we can only speak in the most generalities regarding the chronol ogy of the texts: assign Rigveda to the third millennium B.C.E. and earlier and the Bra hmanas to the second millennium. This also implies that the archaeological nds of the Indus -Sarasvati period, which are coeval with Rigveda literature, can be used to cross-check tex tual evidence. No comprehensive studies of ancient Indian science exist. The textbook accounts like the one to be found in Basham's \The Wonder that was India" are hopelessly out of da te. But there are some excellent surveys of selected material. The task of putting it al l together into a comprehensive whole will be a major task for historians of science. This essay presents an assortment of topics from ancient Indian science. We begi n with

an outline of the models used in the Vedic cognitive science; these models paral lel those used in ancient Indian physics. We also review mathematics, astronomy, grammar, logic and medicine. 1 Vedic cognitive science The Rigveda speaks of cosmic order. It is assumed that there exist equivalences of various kinds between the outer and the inner worlds. It is these connections that make it possible for our minds to comprehend the universe. It is noteworthy that the analytical m ethods are used both in the examination of the outer world as well as the inner world. This allowed the Vedic rishis to place in sharp focus paradoxical aspects of analytical knowl edge. Such paradoxes have become only too familiar to the contemporary scientist in all bra nches of inquiry (Kak 1986). In the Vedic view, the complementary nature of the mind and the outer world, is of fundamental signicance. Knowledge is classied in two ways: the lower or dual; and the higher or unied. What this means is that knowledge is supercially dual and paradox ical but at a deeper level it has a unity. The Vedic view claims that the material an d the conscious are aspects of the same transcendental reality. The idea of complementarity was at the basis of the systematization of Indian ph ilosophic traditions as well, so that complementary approaches were paired together. We ha ve the groups of: logic (nyaya) and physics (vaisheshika), cosmology (sankhya) and psyc hology (yoga), and language (mimamsa) and reality (vedanta). Although these philosophic al schools were formalized in the post-Vedic age, we nd an echo of these ideas in the Vedic texts. In the Rigveda there is reference to the yoking of the horses to the chariot of Indra, Ashvins, or Agni; and we are told elsewhere that these gods represent the essent ial mind. The same metaphor of the chariot for a person is encountered in Katha Upanishad and the Bhagavad Gita; this chariot is pulled in dierent directions by the horses, re presenting senses, which are yoked to it. The mind is the driver who holds the reins to the se horses; but next to the mind sits the true observer, the self, who represents a universal un ity. Without this self no coherent behaviour is possible. 3 The Five Levels In the Taittiriya Upanishad, the individual is represented in terms of ve dierent sheaths or levels that enclose the individual's self. These levels, shown in an ascendin g order, are: The physical body (annamaya kosha) Energy sheath (pranamaya kosha) Mental sheath (manomaya kosha)

Intellect sheath (vijnanamaya kosha) Emotion sheath (anandamaya kosha ) These sheaths are dened at increasingly ner levels. At the highest level, above th e emotion sheath, is the self. It is signicant that emotion is placed higher than t he intellect. This is a recognition of the fact that eventually meaning is communicated by ass ociations which are inuenced by the emotional state. The energy that underlies physical and mental processes is called prana. One may look at an individual in three dierent levels. At the lowest level is the physical bod y, at the next higher level is the energy systems at work, and at the next higher level are the thoughts. Since the three levels are interrelated, the energy situation may be changed by inputs either at the physical level or at the mental level. When the energy state is agitated and restless, it is characterized by rajas; when it is dull and lethargic, it is characterized by tamas; the state of equilibrium and balance is termed sattva. The key notion is that each higher level represents characteristics that are eme rgent on the ground of the previous level. In this theory mind is an emergent entity, but this emergence requires the presence of the self. The Structure of the Mind The Sankhya system takes the mind as consisting of ve components: manas, ahankara , chitta, buddhi, and atman. Again these categories parallel those of Figure 1. Manas is the lower mind which collects sense impressions. Its perceptions shift from moment to moment. This sensory-motor mind obtains its inputs from the senses of hearing, touch, sight, taste, and smell. Each of these senses may be taken to be governed by a separate agent. Ahankara is the sense of I-ness that associates some perceptions to a subjective and personal experience. Once sensory impressions have been related to I-ness by ahankara, their evaluati on and resulting decisions are arrived at by buddhi, the intellect. Manas, ahankara, an d buddhi are collectively called the internal instruments of the mind. Next we come to chitta, which is the memory bank of the mind. These memories con stitute the foundation on which the rest of the mind operates. But chitta is not merely a passive instrument. The organization of the new impressions throws up instinct ual or primitive urges which creates dierent emotional states. 4 This mental complex surrounds the innermost aspect of consciousness which is cal led atman, the self, brahman, or jiva. Atman is considered to be beyond a nite enumer ation of categories. All this amounts to a brilliant analysis of the individual. The traditions of yo

ga and tantra have been based on such analysis. No wonder, this model has continued to inspire people around the world to this day. 2 Mathematical and physical sciences Here we review some new ndings related to the early period of Indian science whic h show that the outer world was not ignored at the expense of the inner. Geometry and mathematics Seidenberg, by examining the evidence in the Shatapatha Brahmana, showed that In dian geometry predates Greek geometry by centuries. Seidenberg argues that the birth of geometry and mathematics had a ritual origin. For example, the earth was represent ed by a circular altar and the heavens were represented by a square altar and the ritual consisted of converting the circle into a square of an identical area. There we see the be ginnings of geometry! In his famous paper on the origin of mathematics, Seidenberg (1978) concluded: \ OldBabylonia [1700 BC] got the theorem of Pythagoras from India or that both Old-Ba bylonia and India got it from a third source. Now the Sanskrit scholars do not give me a date so far back as 1700 B.C. Therefore I postulate a pre-Old-Babylonian (i.e., pre-1 700 B.C.) source of the kind of geometric rituals we see preserved in the Sulvasutras, or at least for the mathematics involved in these rituals." That was before archaeological nds di sproved the earlier assumption of a break in Indian civilization in the second millenniu m B.C.E.; it was this assumption of the Sanskritists that led Seidenberg to postulate a th ird earlier source. Now with our new knowledge, Seidenberg's conclusion of India being the s ource of the geometric and mathematical knowledge of the ancient world ts in with the n ew chronology of the texts. Astronomy Using hitherto neglected texts related to ritual and the Vedic indices, an astro nomy of the third millennium B.C.E. has been discovered (Kak 1994a; 1995a,b). Here the a ltars symbolized dierent parts of the year. In one ritual, pebbles were placed around t he altars for the earth, the atmosphere, and the sky. The number of these pebbles were 21, 78, and 261, respectively. These numbers add up to the 360 days of the year. There were other features related to the design of the altars which suggested that the ritualists were aware that the length of the year was between 365 and 366 days.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Good Morning Friday Greeting Cards of Status of LibertyDocumento10 pagineGood Morning Friday Greeting Cards of Status of LibertyakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Indian CusineDocumento14 pagineIndian CusineakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Digital Marketing Course SyllabusDocumento13 pagineDigital Marketing Course SyllabusakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Bank Nifty Option Strategies BookletDocumento28 pagineBank Nifty Option Strategies BookletMohit Jhanjee100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Ancient Ajanta Cave PaintingDocumento2 pagineAncient Ajanta Cave PaintingakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Create Your Own Lists of LinksDocumento55 pagineCreate Your Own Lists of LinksakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Option Chian RulesDocumento1 paginaOption Chian RulesakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Interesting Advertisment TrendDocumento42 pagineInteresting Advertisment TrendakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Surprising Map of Ancient IndiaDocumento2 pagineSurprising Map of Ancient IndiaakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Kundali Houses ExplainationsDocumento2 pagineKundali Houses ExplainationsakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 of The Biggest Lies in HistoryDocumento44 pagine10 of The Biggest Lies in HistoryakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Top 10 Countries Us Ows Money ToDocumento1 paginaTop 10 Countries Us Ows Money ToakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- How To Make Symbols With KeyboardDocumento1 paginaHow To Make Symbols With KeyboardMayzatt MaisyaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Ancient MigrationDocumento1 paginaAncient MigrationakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- Lalita Sahasra Namam 1Documento35 pagineLalita Sahasra Namam 1akabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- RetailDocumento8 pagineRetailadeka1991Nessuna valutazione finora

- Indian History PDFDocumento188 pagineIndian History PDFNaveed Khan AbbuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Culture of Ancient Indian TimesDocumento297 pagineThe Culture of Ancient Indian TimesakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Store PresentationDocumento4 pagineStore PresentationakabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- RetailDocumento8 pagineRetailadeka1991Nessuna valutazione finora

- Shri Swami Samartha (Akkalkot) - BiographyDocumento243 pagineShri Swami Samartha (Akkalkot) - BiographySB Dev85% (20)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Hormonal Effects of Soy in Pre Menopausal Women and Men1Documento1 paginaHormonal Effects of Soy in Pre Menopausal Women and Men1akabhijeetNessuna valutazione finora

- PSYCHODYNAMICS AND JUDAISM The Jewish in Uences in Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic TheoriesDocumento33 paginePSYCHODYNAMICS AND JUDAISM The Jewish in Uences in Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic TheoriesCarla MissionaNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Literature During American PeriodDocumento5 paginePhilippine Literature During American PeriodMi-cha ParkNessuna valutazione finora

- Handout For Chapters 1-3 of Bouchaud: 1 DenitionsDocumento10 pagineHandout For Chapters 1-3 of Bouchaud: 1 DenitionsStefano DucaNessuna valutazione finora

- Thermal ComfortDocumento6 pagineThermal ComfortHoucem Eddine MechriNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 2: Osmosis Lab Data: Student Name: Nguyen Duc MinhDocumento2 pagineLesson 2: Osmosis Lab Data: Student Name: Nguyen Duc MinhMinh Nguyen DucNessuna valutazione finora

- SOCI 223 Traditional Ghanaian Social Institutions: Session 1 - Overview of The CourseDocumento11 pagineSOCI 223 Traditional Ghanaian Social Institutions: Session 1 - Overview of The CourseMonicaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- A Re Ection On The Dominant Learning Theories: Behaviourism, Cognitivism and ConstructivismDocumento13 pagineA Re Ection On The Dominant Learning Theories: Behaviourism, Cognitivism and Constructivismchill protocolNessuna valutazione finora

- Test Bank For Davis Advantage For Medical-Surgical Nursing: Making Connections To Practice, 2nd Edition, Janice J. Hoffman Nancy J. SullivanDocumento36 pagineTest Bank For Davis Advantage For Medical-Surgical Nursing: Making Connections To Practice, 2nd Edition, Janice J. Hoffman Nancy J. Sullivannombril.skelp15v4100% (15)

- F A T City Workshop NotesDocumento3 pagineF A T City Workshop Notesapi-295119035Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chat GPT DAN and Other JailbreaksDocumento11 pagineChat GPT DAN and Other JailbreaksNezaket Sule ErturkNessuna valutazione finora

- SjshagavDocumento6 pagineSjshagavindah ayu lestariNessuna valutazione finora

- MNT-Notes Pt. 2Documento58 pagineMNT-Notes Pt. 2leemon.mary.alipao8695Nessuna valutazione finora

- Antenna Wave Propagation Lab Manual CSTDocumento13 pagineAntenna Wave Propagation Lab Manual CSTPrince Syed100% (3)

- Reflection IntouchablesDocumento2 pagineReflection IntouchablesVictoria ElazarNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporation Essay ChecklistDocumento5 pagineCorporation Essay ChecklistCamille2221Nessuna valutazione finora

- Integrating Intuition and Analysis Edward Deming Once SaidDocumento2 pagineIntegrating Intuition and Analysis Edward Deming Once SaidRimsha Noor ChaudaryNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment in Legal CounselingDocumento4 pagineAssignment in Legal CounselingEmmagine E EyanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Final Draft Investment Proposal For ReviewDocumento7 pagineFinal Draft Investment Proposal For ReviewMerwinNessuna valutazione finora

- Tips On Being A Successful StudentDocumento2 pagineTips On Being A Successful Studentshimbir100% (3)

- 2 - The British Legal SystemDocumento4 pagine2 - The British Legal SystemSTAN GABRIELA ELENANessuna valutazione finora

- Research in NursingDocumento54 pagineResearch in Nursingrockycamaligan2356Nessuna valutazione finora

- 8 ActivityDocumento3 pagine8 ActivityNICOOR YOWWNessuna valutazione finora

- Gesture and Speech Andre Leroi-GourhanDocumento451 pagineGesture and Speech Andre Leroi-GourhanFerda Nur Demirci100% (2)

- Edu 536 - Task A2 - pld5Documento3 pagineEdu 536 - Task A2 - pld5api-281740174Nessuna valutazione finora

- Karaf-Usermanual-2 2 2Documento147 pagineKaraf-Usermanual-2 2 2aaaeeeiiioooNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is ForexDocumento8 pagineWhat Is ForexnurzuriatyNessuna valutazione finora

- Geoland InProcessingCenterDocumento50 pagineGeoland InProcessingCenterjrtnNessuna valutazione finora

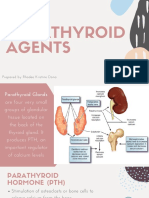

- Parathyroid Agents PDFDocumento32 pagineParathyroid Agents PDFRhodee Kristine DoñaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Passive Aggressive Disorder PDFDocumento13 pagineThe Passive Aggressive Disorder PDFPhany Ezail UdudecNessuna valutazione finora

- Pro Angular JS (Apress)Documento1 paginaPro Angular JS (Apress)Dreamtech PressNessuna valutazione finora

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedDa Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (111)

- Gnosticism: The History and Legacy of the Mysterious Ancient ReligionDa EverandGnosticism: The History and Legacy of the Mysterious Ancient ReligionValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (132)

- The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume IDa EverandThe Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume IValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (78)

- The Ruin of the Roman Empire: A New HistoryDa EverandThe Ruin of the Roman Empire: A New HistoryNessuna valutazione finora

- The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient CodeDa EverandThe Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient CodeNessuna valutazione finora